Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.113 no.9-10 Pretoria sep./oct. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2017/20160318

REVIEW ARTICLE

Resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls: A scoping review of the literature

Sadiyya HaffejeeI; Linda TheronII

IOptentia Research Focus Area, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

IIDepartment of Education Psychology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Childhood sexual abuse is often associated with a number of deleterious psychological and behavioural outcomes for survivors. However, some research suggests that this impact is variable and that some survivors adapt positively. An ability to adapt positively to adversity, under any circumstances, has been termed resilience. Drawing on a socio-ecological understanding of resilience, the aim of this scoping review was to comprehensively map existing empirical studies on resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls and to summarise emerging resilience-enabling factors. We also considered the implications of the findings for practice and research. A total of 11 articles met the criteria for inclusion in the review. Findings from these studies suggest that internal factors (meaning making, optimistic future orientation, agency and mastery) and contextual factors (supportive family, social and educational environments) function interdependently to enable resilience in sexually abused adolescent girls. Practitioners should leverage these complementary and interdependent resilience-enabling mechanisms by encouraging greater involvement of girls in the planning of interventions and by assisting girls in developing meaningful narratives about their abuse experiences. Interventions should also encourage greater involvement from supportive structures, while challenging social and cultural norms that inhibit resilience. Resilience researchers should be cognisant of the paucity of research focusing on resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls as well as the absence of innovative, participatory methods of data collection.

SIGNIFICANCE:

• The review adds to a body of literature on resilience processes with implications for resilience researchers.

• The findings have implications for a range of practitioners (psychologists, social workers, teachers etc.) who work with sexually abused girls.

Keywords: resilience-enabling factors; child sexual abuse; teenage girls; supportive ecologies; positive adaptation

Introduction

In August 2016 the hashtag #1in3 was trending in South Africa. This hashtag represents the pervasiveness of sexual abuse in South Africa (i.e. one in three South Africans has experienced sexual abuse). Following a silent protest at a political meeting, women from diverse backgrounds across South Africa took to social media to share experiences of sexual assault, bringing to the fore South Africa's violent rape statistics. One Twitter user tweeted the following1:

Actually let me just get this straight. In my immediate family - we are 3/3. My mom. My sister. Me. #1in3

Notwithstanding definitional issues as to what constitutes child sexual abuse (CSA), there is agreement on the pervasiveness of CSA in society, with data suggesting an average worldwide rate of 18% to 20%.2 South African CSA data are more alarming: Artz et al.3 found that one in three young people in South Africa have experienced some form of sexual abuse, suggesting that at least 784 967 young people, as of 2016, had been victims of sexual abuse by the time they reached 17 years.

Reading through a number of tweets bearing testimony to the high sexual violence levels in our society, one tweet stands out as most pertinent to this review4:

That little girl that was raped at 15 is doing well, I look myself in the mirror and smile, I've worked so hard to be where I am today. #1in3

This ability to adapt positively to adversity has been the focus of resilience research for the past four decades.5 Resilience researchers address the question of why and how some people adapt positively in spite of significant adversity. This review begins with a similar question, but is distinguished by its specific focus on adolescent girls who have experienced CSA.

Extant literature2,6,7 suggests that CSA is associated with a number of adverse psychological and behavioural consequences for survivors throughout their lifetime. Depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, dissociation, somatisation, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, psychotic and schizophrenic disorders, and suicidal ideation are among the mental health sequelae linked to CSA.8-12 CSA has also been correlated with interpersonal, relationship and sexual difficulties.6,9,13,14 Despite this literature and as evidenced in the tweet above, the impact of CSA is variable; research shows that not all individuals who have experienced CSA develop post-traumatic stress disorder or other psychiatric and behavioural problems.9,15-17 Some research suggests that less than one fifth of CSA survivors show symptoms of serious psychopathology.18,19

Given the high prevalence of sexual violence globally, augmented insights into the resilience processes that buffer the impacts of CSA are particularly relevant. Greater insight into resilience processes potentiates an enhanced understanding of how best to support youth who are at risk for negative developmental outcomes.20 A cursory review of scholarly research suggests a profusion of studies on sexual violence, its determinants and its impact for survivors.2,3,6-9 Although Phasha21 and Resnick et al.12 point out that much of this enquiry has overlooked issues pertaining to resilience, internationally there is a growing body of primary studies that focus on resilience in the aftermath of CSA16. This development is encouraging given the contribution that these insights can make to specialised clinical services and theoretically supported interventions with CSA survivors. This burgeoning interest has also resulted in a limited number of reviews.16,17,22 None of these reviews has, however, focused specifically on resilience processes in adolescent girls who have survived CSA. The reviews by Domhardt et al.17 and Marriot et al.16 included men and women of all ages, whilst Lekganya's22 systematic review focused on studies with adult women. Masten and Wright23 posit that a developmental perspective is necessary when understanding risk and resilience processes; exposure to risks varies with development, as does the individual's processing of the event. Similarly, Supkoff et al.24 suggest that resilience is a developmental process. An individual may be resilient in one developmental period, but not in another. For example, DuMont et al.25 found that resilience decreased by about 18% between adolescence and young adulthood, giving credence to the dynamic nature of resilience processes. Thus, an individual demonstrating resilience in adulthood may not necessarily confirm or explain resilience processes during adolescence.

The need to focus only on adolescent girls' experiences stems from research that talks to the role that gender plays in both increasing girls' vulnerability to sexual assault and the buffering effect it may have in enabling resilience. Research shows that while both girls and boys are at risk of sexual abuse, girls are more vulnerable.26 Patriarchal constructions of masculinity, gender roles assigned to women, social inequality, cultural and parenting practices, and inadequate legal systems increase women's and girls' vulnerability to abuse and also impact their help-seeking behaviour and recovery processes.27-29 Conversely, Jefferis30 adds that while girls may be at higher risk, cultural and contextual factors may also enable strength uniquely for girls. Hirani et al.31 assert that gendered understandings of resilience are necessary as gender roles interact with social and environmental factors to differentially influence how men and women experience and respond to adversity.

Our primary aims in this scoping review are thus to assess the breadth of empirical studies that focus on the resilience of adolescent girls who experienced CSA and to distil the resilience-enabling processes that are common across these studies. Consequently, we consider how findings relating to what enables resilience may be used to inform interventions with adolescent survivors of CSA. We also consider how findings can be used to inform research practices (e.g. choice of research methodologies) within this field and population.

Understanding resilience processes

Although the prevailing critiques of resilience studies often cite the lack of definitional consistency, resilience broadly refers to a process of positive adaptation in the context of severe adversity.23,32,33 This definition infers that resilience is an interactive process, with two critical aspects present: significant adversity and positive adaptation following exposure to adversity.34,35 Rutter36 urges attention to understanding which resources and processes are crucial for adaptation in a given developmental period and/or particular context. This emphasis relates to resilience being a dynamic process. Put differently, resilience is not a single or static individual quality; instead resilience is a process that varies relative to the type of adversity, contextual variables and developmental phase.35,37

The reference to 'dynamic' processes also points to the current ecological systems (also called 'social ecological' - see Ungar38) understanding of resilience. A social ecological understanding of resilience frames the review that we report in this article. This understanding sees individuals as embedded in dynamic ecological systems that enable positive adaptation.30,38 Resilience is, thus, defined as the mutually constructive relationship between an individual and his/her ecological system.38 This reciprocity tasks the individual's social environment to make resilience-enabling resources available, while the individual is simultaneously tasked with moving towards these resources and using them effectively.39

Four decades of research has identified universally occurring protective mechanisms that appear to inform resilience.23,40 Masten41 suggests that these mechanisms reflect adaptive systems that have been influenced by biological and cultural evolution. They go beyond the individual into other social and cultural systems. This underscores the importance of the environment reiterated by other resilience researchers42-43 and references the social ecological context to which Ungar44 speaks.

Masten41(p.6) refers to these mechanisms as 'the short list'. This list (itemised below) draws on qualities of the individual and the social ecology.23 As summarised by Masten41,45 and Masten and Wright23, fundamental adaptive systems include:

- attachment relationships and social support that provide capable, responsive caregiving (in adolescence, this support may take the form of close peer relationships);

- problem-solving and the presence of adequate cognitive abilities that allow adequate information processing (resilience does not require exceptional intelligence, but rather the ability to determine what is happening and what to do23);

- self-regulation skills that allow for the employment of effective emotional and behavioural regulation strategies;

- agency, mastery and self-efficacy, including a positive sense of self, the presence of self-confidence, the motivation to do something differently to succeed, and a sense of control of the environment;

- meaning making (the ability to find meaning or purpose in all experiences), and hope for a better future, justice or better afterlife;

- the influence of culture, traditions and religion as captured in the presence of protective factors such as faith and traditional and cultural belief systems that assign meaning to experiences. Affiliation with religious communities may also provide support and assistance.

Although the above recur in accounts of resilience, Rutter36 cautions that the optimal clinical facilitation of the above protective processes requires an understanding of how the type of adversity, context and/or developmental stage alters their impact and meaningfulness. Thus, to address what is known and not known about how the above resilience processes inform the resilience of adolescent girls who have experienced CSA, we opted for a scoping review of the current literature. We used the above shortlist to structure the findings.

Methodology

The scoping review

Scoping reviews have gained increasing popularity as a way of synthesising research findings46,47 and are broadly a way of determining the research available on a specific topic48. Specifically, they are a form of knowledge synthesis that involves mapping existing literature to get a sense of the breadth and depth of a particular research area.47,49-51 Scoping reviews are typically undertaken to examine the extent, range and nature of the research activity; determine the feasibility of undertaking a full systematic review; summarise and disseminate research findings; and identify gaps in the existing literature.49 As detailed in the introduction, our review matches the aforementioned given the intention to synthesise what is currently known about the resilience processes of adolescent girls who have experienced CSA. This type of scoping review does not stop at the point of summarisation and dissemination of findings, but goes further to try and draw intervention- and research-related conclusions from the existing literature.49

In keeping with the iterative nature of scoping reviews49, our scoping review took place in two phases. Whereas scoping reviews generally begin with a broader, less focused research question which may then be refined, ours began with too narrow a research question. Initially, the focus was only on qualitative and mixed-methods studies of resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls. This first phase was implemented between August 2015 and December 2015. However, after recognising the relative dearth of qualitative studies, we expanded the study scope to include a wider range of study designs, leading to Phase Two (February 2016 to August 2016). Phase Two included qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies of resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls. In both phases, the same search terms and search engines were used. Keywords entered and included in the title and abstract were: (1) resilience OR resilient OR resiliency OR functional outcomes OR positive adjustment OR protective factors AND (2) sexual violence OR rape OR child sexual abuse OR sexual molestation OR sexual assault AND (3) adolescent girls OR girls OR young women. While this inverted process was time-consuming, it allowed for a more comprehensive sense of the existing literature.

Arksey and O'Malley's49 iterative five-stage model guided this review (Table 1). Where appropriate, the recommendations made by Levac et al.47 were included. The sections below offer a description of these stages as incorporated in this review.

Identifying the research question

This scoping activity sought to explore factors promoting resilience in adolescent girls who had experienced CSA. The research question thus focuses on adolescents as opposed to adults or young children, on girls as opposed to women or men, and on sexual abuse and not on other forms of abuse.

Identifying relevant studies

Scoping studies requires transparency and rigour, which are ensured through the comprehensiveness of the data search.49 To achieve this comprehensiveness, we searched a number of different sources: electronic databases, reference lists, university repositories, an online social networking research site, and organisational reports. To ensure access to the correct search engine, we consulted a librarian at North-West University, who provided suggestions regarding keyword combinations and the most comprehensive database to access.

Levac et al.47 suggest that while comprehensiveness and rigour are important, researchers must be cognisant of practicalities such as time, personnel, and budget constraints. Given the reality of these constraints in our review, we established the following inclusion criteria:

- The study was reported in English.

- The study was a primary study. Theoretical overviews, literature syntheses and studies describing therapeutic interventions were excluded.

- The study population comprised only adolescent girls between the ages of 13 and 19 or where the mean age of the sample was below 20 years. The rationale for limiting the review to adolescent girls' resilience processes has been discussed above. Essentially we concur that gender adds a layer of complexity to resilience processes30 and as a dynamic process, resilience is subject to change over an individual's lifespan25,52,53.

- The study focused on resilience processes in girls who had experienced one or more incidents of CSA. We assumed that the authors of each study had adhered to the expectation that resilience studies include only participants who experience a negative event (such as CSA) as adverse and who maintain/regain functional outcomes despite the experience of adversity.54 Studies covering broader incidents of maltreatment, such as neglect or physical and verbal abuse, were excluded. Some researchers55 suggest that it is important to separate different types of childhood adversity, as the association between the exposure and outcome may vary, with different maltreatment types likely to predict different outcomes.

- The study referred to resilience processes or protective factors (individual strengths as well as social-ecological supports found in families, communities, cultural heritage and so forth). As indicated above, resilience was conceptualised as a social-ecological process informed by the universally occurring processes suggested by Masten and Wright23. Studies that addressed one or more of these cardinal processes were included.

- The study was conducted between 1995 and 2016.

Search strategy

Using the keywords and inclusion criteria referred to above, we identified relevant studies via OneSearch, which is a comprehensive electronic search platform that accesses multiple resources, including online resources, journals and books, in one search. Databases in OneSearch that we selected were ERIC, JSTOR, MEDLINE, PsychlNFO, PsychARTICLES, ScienceDirect, Academic Search Premier and CINHAL. We also ran separate searches in Scopus, ScienceDirect, JSTOR and Web of Science.

In addition to searching electronic databases, we conducted a search of South African university repositories, including those of the Universities of Stellenbosch, Pretoria, the Western Cape, the Witwatersrand and Johannesburg. Through this process, we identified six South African dissertations. One dissertation met the inclusion criteria.

We then conducted a manual search of selected articles and literature syntheses that focused on resilience processes and were recommended by resilience researchers or emerged from the electronic search.16,17,22,30 Through this process, we identified five studies; saturation was reached when no new studies were identified.49

We conducted a broad Google search on sexual violence and/or resilience and identified organisations locally and internationally that conducted related research. We then looked through the organisations' outputs, identifying three studies from one organisation, none of which met the inclusion criteria.

Lastly, we accessed an online social networking research site, ResearchGate, to search for specific authors who had previously published on CSA and resilience. In this manner, we accessed two conference papers and two articles. All of these were excluded because of their inclusion of mixed gender samples.

Study selection

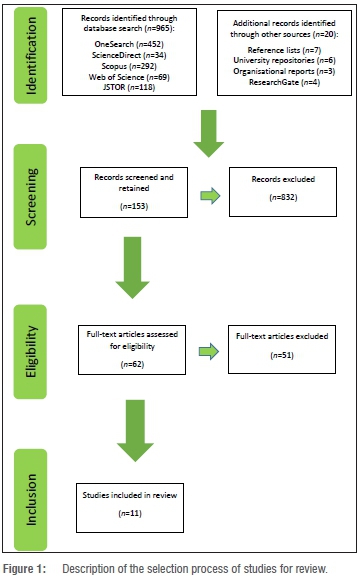

The search generated 985 studies. Titles and abstracts were first screened against the inclusion criteria. In this process, 832 were excluded, and 153 were selected for full-text screening, of which 11 were included in this review. Articles were typically excluded because they did not report girl-specific findings. Figure 1 provides a description of the selection process.

The eligibility of only a small number of studies is not surprising, given the focused nature of this review and the nature of the enquiry. As reported by Daigneault et al.56, a limited number of studies focus on resilience processes in adolescents who have experienced sexual abuse. Other more inclusive reviews of resilience processes in individuals who experienced CSA yielded more studies. For example, Marriot et al.'s16 narrative literature review of resilient outcomes for people (of all ages and genders) who had experienced CSA included 50 studies, and Domhardt et al.'s17 systematic review of resilience processes in survivors (men, women, all age groups) yielded 37 studies.

Charting the data

On completion of the selection process, we adopted a descriptive-analytic approach to chart the data, which involved applying a standardised analytical framework to all included studies.49 We recorded the following information from each of the studies:

- Author(s), year of publication and location (country) of the study

- Source type

- Study population

- Study design/methodology

- Aim of the study

- Results/findings

Appendix 1 in the supplementary material offers a summary of the studies included.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

We conducted a numerical analysis of the extent and nature of the studies included. Of the 11 studies, 4 adopted a research qualitative design, 1 made use of mixed methods, and 6 were quantitative. Only one study employed a participatory approach. Studies were somewhat evenly distributed among low- and middle-income (South Africa, Sierra Leone and Uganda) and high-income (USA and Canada) countries, with five in the former18,21,57-59 and six in the latter56,60-64.

In addition to the above, we used the shortlist summarised by Masten and Wright23 and Masten41 to deductively analyse the contents of the included studies. This shortlist (described above) formed the a priori codes with which we coded the findings sections of the studies. We summarised these findings into two broad domains for ease of understanding: individual factors and resilience-enabling ecologies. In this way, the scope of available literature, as well as key themes across the 11 studies, is summatively presented. Nevertheless, the reader is cautioned that these resilience-enabling factors function interdependently.

Individual factors

Individual factors encompass the ways in which girls contributed to their resilience trajectories by drawing on personal strengths and capabilities. Factors included their capacity to make meaning of and or reappraise the abusive event, displays of agency and self-motivation, self-efficacy, future-oriented beliefs and self-reliance.

Self-reliance and individual resources were perhaps necessary for the participants in some of the reviewed studies. For example, two studies included participants residing in a foster home/care facility57,62, two included girls who were referred to child protection services, indicating multiple risks in the family56,61, and two included African girls in post-war contexts58,59, again suggesting multiple risk factors and disrupted family and community structures, with traditionally supportive environments (such as families) absent.

Opportunities for meaning making, self-regulation and self-efficacy

Included studies suggested that when girls were able to find meaning, they had less negative appraisals and thought about the abuse experiences differently, thereby minimising their significance and consequently adjusting in more positive ways.18,21,56,64

Collings's18 findings associated resilience processes with appraisal of the sexual abuse as either positive or negative, with negative appraisals suggestive of greater psychopathology. In Daigneault et al.'s56 study, the ability to make meaning and to integrate memory and affect was a protective factor linked to disclosure; thus, girls who chose to disclose abuse experiences to a greater number of people had higher scores on meaning making and integration. Their study56 highlights the significance of disclosure for positive reframing and meaning making in the context of supportive relationships; girls were able to form and maintain relationships with people to whom they had disclosed. At follow-up with a sample of participants in this study56, symptom relief and improved resilience were found to be associated with participants' ability to feel and think about the incident differently61. Also apparent were higher scores in the domains of self-esteem.

Phasha21, exploring educational resilience in the aftermath of CSA, found that the young women in her study adapted positively by making sense of their experiences of sexual violence as temporary or learning experiences devoid of self-blame. The absence of self-blaming attitudes meant that the participants were not hampered by thoughts of guilt and helplessness:

I accepted that it's in the past. I mustn't put it in my mind because it will condemn my mind.... I know I have a future even though I did go through that bad stuff... 21

Similarly, participants in Himelein and McElrath's63 study also made use of positive reframing and sought to view the incident as a learning experience or vehicle for change. This belief resulted in new feelings of strength and maturity. As in Phasha's21 study, this attempt to find meaning in the adversity conveyed a sense of hope and optimism for the participants: 'Once I was able to put it aside ... it made a huge difference.'63

Self-regulation was apparent in Archer's57 study; for the 16-year-old participant in her study, placement at a residential facility following sexual abuse contributed to greater independence, expressions of agency, and regulation of her behaviour. Through careful observation and interaction with the care system, she understood what actions she needed to take to manoeuvre successfully and made active choices in controlling her emotions and avoiding trouble. This ability to self-regulate translated into greater ownership of her behaviour and a less blaming attitude.

Optimistic future perspectives

Future orientated beliefs and the presence of goals and aspirations are associated with a positive perception of the world and efforts to adapt in contexts of adversity.65 This factor appeared to play a role in studies of sexually abused girls as well. Edmond et al.62 found the presence of optimism towards the future characteristic of the resilient girls in their study.

Likewise, participants in Phasha's21 study were able to envision a future free from abuse and viewed the future positively rather than with hopelessness: 'My future is very important to me.'21

Archer57 also found evidence of future planning and positive thoughts in her study. Optimistic future planning was evident in both short- and long-term plans. In the quote below, we see the ability to plan for the future, a demonstration of agency, as well as behavioural self-regulation, which highlights the interconnectedness of the various resilience-promoting mechanisms: 'I have a number of dreams for my future ... I must learn to control my temper better as well if I want to become an air hostess ... '57.

Agency and motivational mastery

Jefferis30 refers to 'agentic women' when referencing women's and girls' displays of resolve and decision-making in the face of adversity. This display of volition was apparent in the participants in Denov and MacLure's58 study, in which girls demonstrated resilience by exercising individual agency through personal choices to actively participate or subtly resist oppressive circumstances. This suggests that, in dealing with sexual violence, girls are not merely subservient victims, but rather exhibit a capacity for independent thought and action.58 In much the same way, Archer57 showed that agency extended towards accessing social and legal resources, even if such consequences might be to the detriment of maternal support or material circumstances. Gilligan et al.66 refer to this display of assertion as a way of children retaining a sense of themselves as independent actors and actively seeking out resources that may be of use to them.

Resilience-enabling ecologies

An ecologically grounded understanding of resilience shifts the onus of responsibility for resilience away from the child and instead focuses on the environment to facilitate and make resources available to the child.44 Resources take the form of supportive family environments, peer relationships, social and cultural communities and educational systems.

Attachment relationships

Luthar67 maintains that relationships are central to resilience processes. The significance of relationships is corroborated in a qualitative synthesis of resilience mechanisms in girls: Jefferis30 found that, out of the 38 included studies, every study referred to the presence of a constructive relational context that included positive relationships with other people, spiritual beings or other animals. This finding is further evidenced in this review, with supportive attachment systems emerging as a resilience enabler in 7 of the 11 studies reviewed.

Aspelmeier et al.60 caution that attachment does not completely ameliorate negative CSA outcomes, although it does offer some protection. Findings from Spaccerelli and Kim64 corroborate this statement, with results showing that the presence of supportive parents was related to average or above average social competence and appeared to play an important role in maintaining school performance, activities and peer relationships after the abuse. Here parental support was associated with the ability to appraise the incident in a less negative way. In Archer57, maternal support was linked to the adolescent's sense of identity. Stark et al.59 also found that maternal support was a protective factor against stigma associated with sexual abuse: 'My mother tells me not to worry. She comforts me.'59

These supportive relationships were not limited to parents, but also extended to peers and other sources of support. Denov and MacLure58 found that the girls in their study often relied on other girls in similar situations or older women who had experienced similar difficulties and who were thus able to share information and guide them. This sense of solidarity eased the difficulties they encountered, and the older women created safe spaces and a sense of nurturance:

We ... started sharing our stories [of rape] ... I felt much better after this because I thought that I was the only one to have this happen . the older women helped me.58

The significance of peer relationships during adolescence is widely accepted in developmental literature. The studies included echo the importance of these relationships, with exposure to less negative peer behaviour associated with resilience.62 Stark et al.59 reported that girls drew on close friends to help mitigate stigma. Aspelmeier et al.60 found that higher levels of secure peer attachment/relationships, determined by perceived quality of communication, were related to lower levels of self-related trauma symptoms among CSA survivors. In both Archer's57 and Phasha's21 studies, this circle of support was broadened, with participants seeking support and assistance from teachers, friends, social workers and police officers.

The role of supportive environments did not appear limited to offering nurturing and encouragement; in Stark et al.59, parents and other community members, such as officials and police officers, played a role in negotiating some form of justice. While this role may have implied that the participants might be 'powerless'59(p.222) in negotiating their own fate in certain circumstances, in other circumstances, it pointed to girls' agency in understanding how legal systems worked and how they could afford protection. For example, the participant in Archer's57 study understood early on that reporting abuse would mean removal from her home. While separation from the non-offending parent was difficult, she also understood that such separation offered protection. Both scenarios highlight the possibilities that supportive ecologies hold in these contexts.

Cultural and religious traditions

Two of the South African studies included found evidence of the protective impact of religious beliefs on sexually abused adolescent girls. Phasha21 found that African girls often made meaning of CSA by understanding it as God's will and not their personal responsibility. Phasha linked this belief, which acted as a source of strength and a way to acceptance, to African child-rearing practices being deeply entrenched in religious beliefs and understandings.

In Archer's57 study, the belief in a higher being allowed for greater meaning making and acceptance; the participant's belief in God and regular church and spiritual group attendance assisted her in forgiving those whom she perceived as complicit in the abuse.

Spiritual attributions or meaning making, which included beliefs in 'white magic' and 'spirits', were also noted in a Canadian sample61; however, this finding was specific to the Haitian youth in that sample. The researchers viewed this finding cautiously, given the test instrument's limited cultural sensitivity.

Social, community and educational systems

The importance of school contexts and education was highlighted in three studies.21,57,62 Educational success, engagement in school systems, and certainty regarding educational futures were noted. Phasha21 explained the desire for educational success and commitment to schooling for the girls in her study in terms of racial and ethnic identity. Phasha21 maintains that self-knowledge and self-regard - processes that partially stemmed from a positive racial identity and a strong sense of ethnic identity - allowed African participants to overcome adversity. These beliefs grew, in part, because of apartheid policies of discrimination and, simultaneously, conveyed the importance of education as a vehicle to a better future. In Archer's57 study, getting involved in educational and recreational activities provided a sense of belonging and success, bolstering feelings of confidence and self-esteem.

Edmond et al.62 showed that girls with a resilient trajectory appeared to skip school less frequently, were less likely to get into fights at school, and appeared to have a greater sense of certainty regarding their educational futures than did the comparison sample of symptomatic girls. Approximately 88% of participants with resilient trajectories indicated that they were very sure of their high school plans, with three out of four planning on going to college.62 Findings in this study were reinforced in that participants also scored higher on the future orientation scale, suggesting a more positive view of their futures, and thereby associating education with a better future.

Discussion

Our aim in conducting this scoping review was to examine and understand what was known globally about resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls as well as how this insight may be used to inform clinical practice, intervention and research. A review of the 11 studies included suggests a correlation with protective factors identified in the broader literature on resilience processes in youth. Furthermore, we note the presence of internal and contextual factors that function interdependently to enable resilience in sexually abused adolescent girls. What is novel about these findings is that they are the first to offer an overview of the resilience processes that support adolescent girls from Global South and North contexts to adjust well following CSA.

Taking heed of Levac et al.'s47 counsel to reviewers to consider the implications of the results and what they may mean for 'research, policy and practice', we consider what the findings from this review imply for resilience researchers and practitioners working with sexually abused girls.

Implications for practice

Findings from the review highlight possible points at which practitioners (e.g. psychologists, social workers, child care workers and health workers) may act in order to leverage resilience-enabling practice. These actions include assisting girls in the development of meaningful narratives about their abuse experiences; greater consultation with, and inclusion of, affected girls in planning of interventions; challenging of social and cultural norms; and eliciting and encouraging greater involvement from supportive structures.

The findings suggest that adolescent girls themselves are resourceful and display agency in responding to sexual abuse. Cognitive reappraisals and positive reframing of the incident impacted feelings of self-efficacy and allowed some to minimise the impact CSA had on them and their futures; these girls were, thus, able to view the future optimistically. Opportunities for intervention in fostering resilience are thus apparent: without minimising the experience, girls can be assisted to develop a meaningful narrative of the abuse and to envisage a future.56 Collings18 suggests that cognitive appraisals can be altered; thus, employing cognitive change strategies holds promise in interventions with this group.

Denov and MacLure58 also draw on their findings of agency demonstrated by participants to recommend that interventions acknowledge the volition of adolescent girls and intervene in ways whereby the voices and perspectives of youth are elicited and incorporated in intervention programmes. Interventions should provide opportunities for girls' 'demonstrable capacity of thought and action' to be acknowledged.58(p82)

We found strong evidence of the role of attachment relationships in enabling resilience trajectories, beginning with supportive parents and extending to enabling community members, highlighting the importance of these structures. In contrast, Stark et al.59 reported that while social networks appeared to be vital in offering support and promoting psychosocial recovery in the aftermath of abuse, such networks did not consistently respond positively to the needs of the adolescent girls. In some instances, girls were stigmatised, blamed or socially excluded by family and community members because of the sexual abuse; in these instances, social ecologies impeded recovery processes.59 Jefferis30 also notes that social, cultural and community norms around gender roles -which value women's and girls' submissiveness and prioritise roles of caretaking - sometimes act to the detriment of resilience processes for girls and women. Stark et al.59, speaking to their findings on the role of stigma and shame, recommend that interventions address destructive social norms that perpetuate stigma. Thus, interventions aimed at adolescent girls who have experienced CSA should take cognisance of the potential and risks that social ecologies, such as families and communities, present.

Implications for future research

What is apparent from this review is the paucity of research focusing on resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls. After a thorough search strategy using multiple databases, only 11 exclusive studies were identified. To date, studies on resilience processes in youth have usually incorporated different forms of adversity, seldom focusing on only one risk factor. Furthermore, resilience studies with children and youth often include both male and female participants. As discussed earlier, gender adds a layer of complexity to resilience processes; gender roles, societal norms and contextual factors impact how men and women experience and respond to stressors.67 Where resilience processes were examined specifically in relation to sexual abuse, participants were often adult women and not adolescent girls. This finding suggests a need for further explorations of resilience processes specific to sexually abused adolescent girls. Limited understanding of resilience processes in this group may result in interventions that are not gender and/or developmentally sensitive, lack coherence for adolescent girls, and may be ineffective.

Although our review revealed a complementary mix of both qualitative and quantitative studies, there was an absence of child-centred participatory approaches. Only one of the included studies58 engaged girls as co-researchers. This decision was motivated by their belief that the inclusion of girls as co-researchers would enhance the richness of the discussion and thus the quality of data. Additionally, for the researchers58, participatory methods also held the potential of involving the girls in an educational, empowering and purposeful activity. While there is value in all empirical studies on CSA and resilience processes, regardless of methodology, we add to a growing call for the inclusion of youth in research about them.62,68 Alderson68 asserts that youth are key sources of information about their own experiences and inclusivity results in more insightful research. Participatory methods position youth as knowledge producers. Engaging youth as knowledge producers in research has been successfully implemented in projects focused on finding solutions to social challenges, like HIV, sexual vulnerability and teenage pregnancy.69 Moreover, participatory methods are youth friendly, allowing for greater accessibility and the redress of power imbalances between the researcher and the participants.70 Such methods have been recommended for use in studies on both gender violence and youth resilience. Mitchell71 suggests that studies focused on gender violence require methods that allow for engagement and disengagement of participants, so that participants themselves can structure the pace. Participatory approaches allow for this control. Similarly, Theron72 suggests that qualitative approaches that embrace creative, innovative data collection techniques result in more comprehensive understandings of youth resilience processes.

What the discussion above has reinforced is that CSA survivors are not passive victims acting without agency; they are capable of reflecting on and negotiating change and solutions to the difficulties they encounter.73 Participatory methods in particular hold the potential for enhancing this process; a participatory approach creates avenues for youth voices to be heard, encourages displays of agency and provides a platform for empowerment.74

Given the possibilities that participatory approaches present in terms of richer, more in-depth understandings generated by engaged youth themselves and their suitability for use specifically with sexually abused girls in terms of potentiating agency, it appears that researchers need to consider these approaches when exploring resilience processes.

Conclusion

This scoping review closely mirrored the first five steps outlined by Arksey and O'Malley49, and while constrained by the limited number of studies available, it provided valuable insight into the resilience processes of sexually abused adolescent girls. The omission of the optional final step (consultation with key stakeholders to provide additional information and insight) described by Arksey and O'Malley49 presents a limitation. It is possible that such a dialogue could have provided further knowledge regarding enabling processes and added insight into how this knowledge could be disseminated and translated into practice. Notwithstanding this possibility, the coherence of these findings with the shortlist summarised by Masten and Wright23 is compelling and, following Rutter36, adds developmental- and risk-specific knowledge to the body of literature on resilience processes. The greater contribution of the findings is in the possibilities they offer for practitioners and researchers to exact change in adolescent girls' recovery processes and enhance the field of resilience studies in youth.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the PhD bursary provided to S.H. by Optentia Research Focus, North-West University as well as the Networks of Change and Well-being Project (funded by the International Development Research Centre).

Authors' contributions

Both authors conceptualised the article; S.H. wrote up the method, reviewed the literature and drafted the initial themes; L.T. assisted in refining the themes; and both authors contributed to the discussion.

References

1. Hastie N [Nina Hastie@THATninahastie]. Actually let me just get this straight. In my immediate family - we are 3/3. My mom. My sister. Me. #1in3 [Twitter]. 2016 Aug 07 [cited 2016 Aug 1θ]. Available from: https://twitter.com/thatninahastie [ Links ]

2. Collin-Vezina D, Daigneault I, Hebert M. Lessons learned from child sexual abuse research: Prevalence, outcomes, and preventive strategies. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7, Art. #22, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-7-22 [ Links ]

3. Artz L, Burton P Ward C, Leoschut L, Phyfer J, Lloyd S, et al. Sexual victimisation of children in South Africa. Technical report. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation; 2016. [ Links ]

4. Matomane N [Nolundi Matomane@NolundiMatomane]. That little girl that was raped at 15 is doing well, I look myself in the mirror and smile, I've worked so hard to be where I am today. #1in3 [Twitter]. 2016 Aug 07 [cited 2016 Aug 10]. Available from: https://twitter.com/nolundimatomane [ Links ]

5. Masten AS. Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:921-930. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407000442 [ Links ]

6. Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: A systematic review of reviews. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(7):647-657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003 [ Links ]

7. Hillberg T, Hamilton-Giachitsis C, Dixon L. Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: A systematic approach. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(1):38-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524838010386812 [ Links ]

8. Cashmore J, Shackel R. The long term effects of child sexual abuse. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2013. CFCA PAPER NO. 11 2013. http://cdn.basw.co.uk/upload/basw_103914-1.pdf [ Links ]

9. Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Neglect. 2007;31(3):211-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004 [ Links ]

10. Finkelhor D. The prevention of childhood sexual abuse. Future Child. 2009;19(2):169-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/foc0.0035 [ Links ]

11. Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:119-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022891005388 [ Links ]

12. Resnick HS, Guille C, McCauley JL, Kilpatrick DG. Rape and other sexual assault. In: Southwick SM, Litz BM, Charney D, Friedman MJ, editors. Resilience and mental health: Challenges across a lifespan. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 218-237. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511994791.017 [ Links ]

13. Lalor K, McElvaney R. Child sexual abuse, links to later sexual exploitation/high risk sexual behaviour and prevention/treatment programmes. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;(11):159-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524838010378299 [ Links ]

14. Miron LR, Orcutt HK. Pathways from childhood abuse to prospective revictimisation: Depression, sex to reduce negative affect, and forecasted sexual behaviour. Child Abuse Neglect. 2014;38(11):1848-1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.004 [ Links ]

15. McElharan M, Briscoe-Smith A, Khaylis A, Westrup D, Hayward C, Gore-Felton C. A conceptual model of post traumatic growth among children and adolescents in the aftermath of sexual abuse. Couns Psychol Q. 2012;25(1):73-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2012.665225 [ Links ]

16. Marriot C, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Harrop C. Factors promoting resilience following childhood sexual abuse: A structured, narrative review of the literature. Child Abuse Rev. 2014;23:17-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/car.2258 [ Links ]

17. Domhardt M, Munzer A, Fegert JM, Lutz G. Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: A systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;(16)4:476-493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557288 [ Links ]

18. Collings S. Surviving child sexual abuse. The social work practitioner-researcher. 2003;15(1):97-110. [ Links ]

19. Kendall-Tacket KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children. A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. In: Bull, R, editor. Children and the law: The essential readings. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1993. Psychological Bulletin, 113(1):164-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164 [ Links ]

20. Luthar SS, Ciccheti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164 [ Links ]

21. Phasha NT. Educational resilience among African survivors of child sexual abuse in South Africa. J Black Stud. 2010;40(6):1234-1253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0021934708327693 [ Links ]

22. Lekganya I. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with resilience among survivors of sexual abuse [master's thesis]. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape, 2015. [ Links ]

23. Masten A, Wright M. Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery and transformation. In: Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Hall JS, editors. Handbook of adult resilience. New York: The Guilford Press, 2010. p. 213-237. [ Links ]

24. Supkoff LM, Puig J, Sroufe LA. Situating resilience in developmental context. In: Ungar M, editor. The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. Springer: New York, 2012. p. 127-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3_12 [ Links ]

25. Dumont KA, Widom CS, Czaja SJ. Predictors of resilience in abused and neglected children grown up: The role of individual and neighbourhood characteristics. Child Abuse Neglect. 2007;31:255-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.015 [ Links ]

26. Dartnell E, Jewkes R. Sexual violence against women: The scope of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27:3-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bobgyn.2012.08.002 [ Links ]

27. Lalor K. Child sexual abuse in sub-Saharan Africa: Child protection implications for development policy makers and practitioners. Development Research Briefings no. 3. Dublin: Centre for Development Studies, University College Dublin; 2005. Available from: http://arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=aaschsslrep [ Links ]

28. Mathews S, Loots L, Sikweyiya Y Jewkes R. Sexual abuse. In: Van Niekerk A, Suffla S, Seedat M, editors. Crime violence and injury in South Africa: 21st century solution for child safety. Johannesburg: Psychological Society of South Africa; 2012. p. 1-7. [ Links ]

29. Seedat M, Van Niekerk A, Jewkes R, Suffla S, Ratele K. Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):1011-1022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60948-x [ Links ]

30. Jefferis T. Resilient black South African girls in contexts of adversity: A participatory visual study [PhD thesis]. Vanderbijlpark: North West University; 2016. [ Links ]

31. Hirani S, Lasiuk G, Hegadohen K. The intersection of gender and resilience. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(6-7):455-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12313 [ Links ]

32. Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227 [ Links ]

33. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:857-885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004156 [ Links ]

34. Wright MO, Masten AS. Pathways to resilience in context. In: Theron LC, Liebenberg L, Ungar M, editors. Youth resilience and culture: Commonalities and complexities. New York: Springer; 2015. p. 3-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9415-2_1 [ Links ]

35. Rutter M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1094:1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.002 [ Links ]

36. Rutter M. Annual research review: Resilience - Clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2013:54(4):474-487. http://dx.doi.10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02615.x [ Links ]

37. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316-331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x [ Links ]

38. Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x [ Links ]

39. Hall Am, Theron L. How school ecologies facilitate resilience among adolescents with intellectual disabilities: Guidelines for teachers. S Afr J Educ. 2016;36(2):1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/saje.v36n2a1154 [ Links ]

40. Wright MO, Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In: Goldstein S, Brooks RB, editors. Handbook of resilience in children. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 15-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_2 [ Links ]

41. Masten AS. Promoting resilience in development: A general system for frameworks of care. In: Flynn R, Dudding PM, Barber JG, editors. Promoting resilience in child welfare. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press; 2006. p. 3-17. [ Links ]

42. Theron LC, Theron A. Positive adjustment to poverty: How family communities encourage resilience in traditional African contexts. Cult Psychol. 2013;19(3):391-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13489318 [ Links ]

43. Panter-Brick C. Culture and resilience: Next steps for theory and practice. In: Theron LC, Liebenberg L, Ungar M, editors. Youth resilience and culture - Commonalities and complexities. Dordrecht: Springer; 2015. p. 233-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9415-2_17 [ Links ]

44. Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38(2):218-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [ Links ]

45. Masten AS. Resilience in development: Early childhood as a window of opportunity. Presented at: ECHD Symposium; 2015 April 24; Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA. [ Links ]

46. Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopolous A, McEwn SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Syn Methods. 2014;5(4):371-385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123 [ Links ]

47. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69-78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [ Links ]

48. Woznowski-Vu A, Da Costa C, Turgeon-Provost F, Dagenais K, Roy-Mathie B, Aggban M, et al. Factors affecting length of stay in adult outpatient physical rehabilitation: A scoping review of the literature. Physiother Can. 2015;67(4):329-340. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2014-75 [ Links ]

49. Arskey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ Links ]

50. Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update: Scoping the scope of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015 [ Links ]

51. Peters M, Godfrey CM, Mcinerney P Baldini Soares C. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:141-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [ Links ]

52. Egeland B, Carlson E, Sroufe LA. Resilience as a process. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5(4):517-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006131 [ Links ]

53. Ciccheti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organisation in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9(4):797-815. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579497001442 [ Links ]

54. Van Rensburg A, Theron L, Rothman S. A review of quantitative studies of South African youth resilience: Some gaps. S Afr J Sci. 2015;111(7-8), Art. #2014-0164, 9 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/SAJS.2015/20140164 [ Links ]

55. Afifi TO, Macmillan HL. Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(5):266-272. [ Links ]

56. Daigneault I, Tourigny M, Cyr M. Description of trauma and resilience in sexually abused adolescents. J Trauma Prac. 2004;3(2):23-47. https://doi.org/10.1300/j189v03n02_02 [ Links ]

57. Archer E. Exploring the phenomenon of resilience with a child survivor of abuse [master's thesis]. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2005. [ Links ]

58. Denov M, MacLure R. Engaging the voices of girls in the aftermath of Sierra Leone's Conflict: Experiences and perspectives in a culture of violence. Anthropologica. 2006;48(1):73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/25605298 [ Links ]

59. Stark L, Landis D, Thomson B, Potts A. Navigating support, resilience, and care: Exploring the impact of informal social networks on the rehabilitation and care of young female survivors of sexual violence in northern Uganda. Peace Confl. 2016;22(3):217-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pac0000162 [ Links ]

60. Aspelmeier JE, Elliot AN, Smith CH. Childhood sexual abuse, attachment, and trauma symptoms in college females: The moderating role of attachment. Child Abuse Neglect. 2007;31:549-566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.002 [ Links ]

61. Daigneault I, Cyr M, Tourigny M. Exploration of recovery trajectories in sexually abused adolescents. J Aggres Maltreat Trauma. 2007;14(1-2):165-185. https://doi.org/10.1300/j146v14n01_09 [ Links ]

62. Edmond T, Auslander W, Elze D, Bowland S. Signs of resilience in sexually abused adolescent girls in the foster care system. J Child Sex Abuse. 2006;15(1):1-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J070v15n01_01 [ Links ]

63. Himelein MJ, McElrath JV. Resilient child sexual abuse survivors: Cognitive coping and illusion. Child Abuse Neglect. 1996;20(8):747-758. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(96)00062-2 [ Links ]

64. Spaccarelli S, Kim S. Resilience criteria and factors associated with resilience in sexually abused girls. Child Abuse Neglect. 1995;19(9):1171-1182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(95)00077-L [ Links ]

65. Malindi MJ. Swimming upstream in the midst of adversity: Exploring resilience-enablers among street children. J Soc Sci. 2014;39(3):265-274. [ Links ]

66. Gilligan,R, De Castro EP Vanistendael S, Warburton J. Learning from children exposed to sexual abuse and sexual exploitation: Synthesis report of the Bamboo project study on child resilience. Geneva: Oak Foundation; 2004. [ Links ]

67. Luthar SS. Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In: Cichetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Development psychopathology. Vol 3: Risk, disorder and adaptation. New York: Wiley; 2006. p. 739-795. [ Links ]

68. Alderson P. Children as researchers: Participation rights and research methods. In: Christensen P, James A, editors. Research with children: Perspectives and practices. New York: Routledge; 2000. p. 276-291. [ Links ]

69. Stuart J. Youth as knowledge producers: Towards changing gendered patterns in rural school with participatory arts-based approaches to HIV and AIDS. Agenda. 2011;24(84):53-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2010.9676309 [ Links ]

70. Didkowsky N, Ungar M, Liebenberg L. Using visual methods to capture embedded processes of resilience for youth across cultures and contexts. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(1):2-18. [ Links ]

71. Mitchell C. Doing visual research. London: Sage; 2011. [ Links ]

72. Theron LC. Resilience research with South African youth: Caveats and ethical complexities. S Afr J Psychol. 2012;42(3):333-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124631204200305 [ Links ]

73. Buthelezi T, Mitchell C, Moletsane R, De Lange N, Taylor M, Stuart J. Youth voices about sex and AIDS: Implications for life skills education through the 'Learning Together' project in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Inclusive Educ. 2007;11(4):445-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110701391410 [ Links ]

74. Mitchell C, De Lange N, Stuart J, Moletsane R, Buthelezi T. Children's provocative images of stigma, vulnerability and violence in the age of AIDS: Re-visualisations of childhood. In: De Lange N, Mitchell C, Stuart J, editors. Putting people in the picture. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2007. p. 59-71. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sadiyya Haffejee

sadiyya.haffejee@gmail.com

Received: 21 Oct. 2016

Revised: 02 Mar. 2017

Accepted: 23 May 2017