Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Science

versão On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.113 no.3-4 Pretoria Mar./Abr. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2017/20160008

RESEARCH ARTICLE

A historical assessment of sources and uses of wheat varietal innovations in South Africa

Charity R. Nhemachena; Johann Kirsten

Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

We undertook a historical review of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa from 1891 to 2013, thus extending the period of previous analyses. We identified popular wheat varieties, particularly those that form the basis for varietal improvements, and attempted to understand how policy changes in the wheat sector have affected wheat varietal improvements in the country over time. The empirical analysis is based on the critical review of information from policies, the varieties bred and their breeders, the years in which those varieties were bred, and pedigree information gathered from the journal Farming in South Africa, sourced mainly from the National Library of South Africa and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) database. A database of the sources and uses of wheat varietal innovations in South Africa was developed using information from the above sources. The data, analysed using trend and graphical analysis, indicate that, from the 1800s, wheat varietal improvements in the country focused on adaptability to the production area, yield potential and stability and agronomic characteristics (e.g. tolerance to diseases, pests and aluminium toxicity). An analysis of the sources of wheat varietal improvements during the different periods indicates that wheat breeding was driven initially by individual breeders and agricultural colleges. The current main sources of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa are Sensako, the Agricultural Research Council's Small Grain Institute (ARC-SGI) and Pannar. The structural changes in the agricultural sector, particularly the establishment of the ARC-SGI and the deregulation of the wheat sector, have helped to harness the previously fragmented efforts in terms of wheat breeding. The most popular varieties identified for further analysis of cost attribution and the benefits of wheat varietal improvements were Gariep, Elands and Duzi.

SIGNIFICANCE:

• These findings form the basis for the next analysis focusing on the attribution of the benefits and costs in terms of investment in wheat breeding in South Africa.

Keywords: variety improvement; wheat research; Agricultural Research Council

Introduction and background

The driving factors for investment in crop varietal innovations include the need to improve (1) yield potential, (2) resistance/tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses and (3) nutritional and processing quality.1,2 Greater investments in agricultural research and development (R&D), particularly varietal innovations, are necessary to increase and sustain agricultural productivity, as well as to address challenges such as poverty, food security, adaptation to climate change, increased weather variability, water scarcity and the volatility of prices in global markets.3 The World Bank's 2008 Development Report argued that productivity gains through innovations that address increasing scarcities of land and water remain the main source of growth in agriculture and a primary source of increased food and agricultural production to feed the increasing demand. Innovations such as crop varietal improvements need to focus beyond raising productivity to addressing additional challenges such as water scarcity, risk reduction, improved product quality and environmental protection.

Du Plessis4 reported that the first wheat production in South Africa occurred in the winter of 1652 when Jan van Riebeeck planted the first winter wheat. This development in the 1600s was the foundation of all wheat production and subsequent breeding programmes to date. Despite the first production of wheat in the 1600s, wheat varietal breeding was reported to have been established more than two centuries later in 1891.5 The focus of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa addresses the following cultivar characteristics: adaptability to the production area, yield potential and stability, and agronomic characteristics (e.g. tolerance to diseases, pests and aluminium toxicity). The wheat varietal improvement sector consists of three main actors: the Small Grain Institute of the Agricultural Research Council (ARC-SGI; established in 1976 as the then Small Grains Centre); Sensako, established in the mid-1960s (becoming autonomous in 1999 after functioning as part of Monsanto); and Pannar (entering the wheat breeding sector in the 1990s).5

Periodic assessment of plant breeding is required to assess the benefits of ongoing investment to allow: (1) temporary constraints that could permanently hinder the identification of crop varietal improvements to be addressed; and (2) desirable characteristics - such as quality, quantity and environmental impact - to be identified and prioritised.6 The main objective of this study was to undertake a historical assessment of the sources and uses of wheat varietal innovations in South African agriculture. Specifically, we focused on the historical evolution of wheat varietal improvements in the country between 1891 and 2013, including the identification of popular varieties and their history, sources and uses. This assessment complements earlier efforts by Smit et al.5, Van Niekerk7, De Villiers and Le Roux8 and Stander9, firstly by extending the period of analysis from early breeding periods in the early 1900s to 2013. Furthermore, the current empirical analysis is critical in helping to identify popular wheat varieties that have been bred and grown for long periods (particularly among current varieties in the market). These varieties form the basis for analysing wheat varietal improvements in South Africa, which is the focus of a forthcoming paper in which further analysis looks at the parental history of the selected varieties from the current analysis, and develops an empirical model for the attribution of costs and benefits of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa.

Review of commercial wheat production and breeding in South Africa

Wheat production in South Africa

The South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries3 reported that the precise origin of wheat is not known, but there is evidence that the crop evolved from wild grasses somewhere in the Near East. Wheat is reported to have likely originated from the Fertile Crescent in the upper reaches of the Tigris-Euphrates drainage basin. Commercial wheat production in South Africa started in the early 1910s with varieties brought by the Dutch traders to Cape Town (then the Cape of Good Hope). Wheat is the second most important grain crop produced in South Africa after maize. In South Africa, the main uses of wheat are human consumption (especially for making flour for the bread industry), industrial (important sources of grain for alcoholic beverages, starch and straw), and animal feed (bran from flour milling as an important source of livestock feed, grain as animal feed).3

There are two basic types of commercially cultivated wheat in South Africa, which differ in genetic complexity, adaptation and use: (1) bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) and (2) durum wheat (Triticum turgidum). Durum wheat was derived from the fusion of two grass species some 10 000 years ago, whereas bread wheat was derived from a cross between durum wheat and a third grass species about 8000 years ago.10 Bread wheat and durum wheat are used to make a range of widely consumed food products; for example, bread wheat is processed into leavened and unleavened breads, biscuits, cookies and noodles and durum wheat is used to make pasta (mainly in industrialised countries), as well as bread, couscous and bulgur (mainly in the developing world).10 South Africa mainly produces bread wheat; durum wheat represents a very small percentage of the annual wheat production in the country.

Wheat is produced in 32 of South Africa's 36 crop production regions. The main wheat-producing provinces are the Western Cape (winter rainfall), Free State (summer rainfall) and Northern Cape (irrigation).

Mpumalanga (irrigation) and North West (mainly irrigation) are other important wheat-producing provinces.11 The annual wheat production in South Africa ranges from 1.5 to 3 million tonnes, with productivity rates of 2-2.5 tonnes/ha under dryland (Figure 1) and at least 5 tonnes/ ha under irrigation. However, wheat production has been decreasing in recent years. Smit et al.5 argue that efficiency, productivity and quality in wheat production has increased over time and some of the contributing factors include research efforts from various disciplines such as plant breeding, agronomy, crop physiology and crop protection. For example, the productivity levels for dryland wheat have increased from less than 0.5 tonnes/ha in 1936 to more than 3.5 tonnes/ha in 2015 (Figure 1).12 A study by Purchase13 reported an 87% improvement in yield and a 20% improvement in baking quality between 1930 and 1990. Local production of wheat mainly comes from the Western Cape (contributing about 650 000 tonnes), Free State (580 000 tonnes), Northern Cape (300 000 tonnes), North West (162 000 tonnes) and Mpumalanga (92 000 tonnes). South Africa is a net wheat importer and imports about 300 000 tonnes of wheat per annum.3

Wheat production in South Africa occurs in both summer and winter rainfall regions. Most of the production (at least 50%) happens under dryland conditions. In the summer rainfall region, at least 30% of the total harvest is produced under irrigation.14 Production under irrigation has a higher yield potential than dryland wheat production. Dryland productivity in South Africa is very low compared to that of the major wheat-producing countries in the world. Pannar14 attributes the 'slower than expected progress in yield increases of local breeding programmes' to stringent quality requirements for new varieties, as well as variable climatic conditions (including dry, warm winters), low soil fertility, new diseases such as yellow/stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis) emerging in 1996 and the emergence of new pathotypes, the introduction of the Russian wheat aphid in 1978, and a new biotype in 2005. These factors caused wheat breeding programmes to 'discontinue many promising germplasm lines'14 despite their highly promising yield potential, as they were susceptible to new diseases and pests. The focus in wheat breeding shifted to producing varieties resistant in terms of specific agronomic characteristics (e.g. pest and disease resistance) and to good-quality varieties, as opposed to high-yielding varieties.14

Evolution of crop production and breeding in agriculture

Various studies have reviewed the historical changes and evolution of crop production and breeding. Examples of these studies include those of Chigeza et al.6, Byerlee and Moya15, Heisy et al.16, Grace and Van Staden17 and This et al.18 Here we briefly review these studies to understand the approaches used and some of the major findings and their implications for this paper.

In a study focusing on analysing the impact of international wheat breeding research in the developing world between 1966 and 1990, Byerlee and Moya15 analysed the origins and trends of varieties released by national agricultural research systems (NARS) of 38 collaborating countries. The analysis of wheat varieties released by NARS included the listing of over 1300 varieties and information of their pedigrees, ecological niches and area planted. The information was used to estimate the benefits of wheat breeding on genetic yield and changes in traits such as disease resistance and quality. Byerlee and Moya15 found an increasing proportion (84% by 1986-1990) of spring bread wheat varieties originating directly from varieties of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) or those with a CIMMYT parent, especially among small NARS. They also found that larger NARS used their own crosses to develop more than half of the varieties released. The analysis of wheat releases by NARS with respect to type of variety (winter bread wheat and durum wheat) and growth habit was also done for every 5-year period between 1966 and 1990. In this study we followed a similar approach to develop a comprehensive database of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa.

Smit et al.5 summarised wheat cultivars released in South Africa between 1983 and 2008. The current study extends the analytical period to 1891 and 2013. In addition, we build on these earlier efforts to compile a comprehensive database that forms the basis for estimating the benefits and costs attributed to wheat varietal improvements in South Africa. Another addition in the current study is the provision of the institutional evolution of wheat breeding which was not included in Smit et al.'s5 paper. Furthermore, the focus of Smit et al.5 was more agronomic, while the current paper focuses more on the economics side of wheat-breeding developments over the study period. Also, despite listing varieties released from 1983 to 2008, Smit et al.5 do not provide a detailed historical evolution of wheat varietal improvements in the country.

Data and research methods

The empirical analysis is based on the critical review of information from policies, varieties bred and their breeders, years when varieties were bred, and pedigree information, as gathered from the journal Farming in South Africa, sourced mainly from the National Library of South Africa and the CIMMYT database. The focus was to identify the sources (institutions and individuals) of wheat varietal improvement innovations; where the innovations were used (areas where the wheat varieties were grown); factors driving the innovations; and the types of wheat varietal innovations. The study analysed the wheat varieties released and/or introduced in South Africa during the period 1891-2013. A database of sources and uses of wheat varietal innovations in South Africa was developed using information from the above sources. The database shows that the wheat in South Africa has been a subject of breeding endeavours for more than two centuries, and wheat varietal improvement has rapidly expanded, particularly in the past four decades.

Based on previous studies6,15-18, the data were analysed using trend and graphical analysis. The analysis also considered geographical region/ area, as well as wheat type and growth habit. Although the database is incomplete and undoubtedly contains errors, it is to date the most comprehensive database available on the history of wheat varietal improvement in South Africa. This database will form the basis for further analysis focusing on the attribution of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa and their costs and benefits.

Liebenberg and Pardey19 discussed historical evolution in order to document and describe major developments in the agricultural sector over the 20th and early-21st centuries and the changing policy and institutional environment of public support for agricultural R&D in South Africa. The article by Liebenberg and Pardey19 was used to set the historical and policy context for further analysis, and the quantification and consideration of changes in public agricultural R&D investments between 1880 and 2007. We use the approach of Liebenberg and Pardey to discuss historical changes in the wheat sector and how they have shaped varietal improvements over the years.

Results and discussion

Key developments and early history of wheat varietal improvements

Wheat production was first initiated in South Africa by Jan van Riebeeck during the winter of 1652 at the Cape of Good Hope.4 Wheat production subsequently expanded, and by 1684 there were some exports to India.7 However, South Africa is currently a net importer of wheat. The original cultivars produced at that time originated from Europe and the East Indies, and were brought by the early settlers and trading vessels. The selection criteria for the new varieties were then focused on adaptability to the new environment, such as resistance to stem rust, periodic droughts and wind damage. Table 1 summarises the key developments (institutional and policy) throughout the history of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa from the 1600s.

The first wheat breeding programme reportedly began in 1891 in the Western Cape Province.20 The initial series of artificial crosses between varieties was conducted in 1902 and 1904 to retain the successful resistance of Rieti wheat while replacing its poor milling quality and tendency to shed grain prior to harvesting.7 This undertaking marked the beginning of modern wheat breeding in South Africa. The early crosses were reported to have produced only three varieties of value, which formed the basis for the first cultivars (Union, Darlvan and Nobbs) bred in South Africa. These developments preceded Neethling's first wheat breeding efforts in 1913 at the Elsenburg Research Station near Stellenbosch. The wheat breeding research efforts at the Elsenburg Research Station led to the release of at least 26 wheat varieties, which remained dominant between 1914 and 1961. Examples of the varieties released during that time include Unie17, Unie28, Unie31, Unie52 and Unie81 (all released in 1914), with Unie52 dominating between 1917 and 1927.7

The next release of an early wheat variety - Kleintrou (a selection from Potchefstroom Agricultural College) - occurred in 1916. Kleintrou was directly used as a parent in at least six wheat varieties (including Farrertrou, Koalisie, Stirling, Sonop and Eleksie) between 1933 and 1958. The wheat varieties known as Bobriet and Gluretty (retaining Rieti wheat as one of the parents), released in 1925, were cultivars created from crosses after this period of testing and reselection. The Gluretty variety dominated, replacing Unie52 before succumbing to rust infection and being replaced by six new varieties released in 1933 (of these, Pelgrim, Stirling and Koalisie were successful). The post-1933 breeding period included the first use of interspecific crosses, including Medeah (a Triticum durum wheat with excellent rust resistance, used in South Africa since about 1850) and McFadden (originating from the USA, using Marquis and Jaroslav Emmer to produce the famous Hope and H44 wheat varieties). Long-used and adapted varieties, such as Nobbs, Van Niekerk, Florence and Kleintrou, were also consistently used in the new releases. Of all the varieties released, Stirling had the greatest impact on wheat production in the Western Cape - because of its resistance to stem rust (a resistance inherited from Rieti and Medeah), as well as its adaptability and quality (inherited from Comeback) - and remained dominant until the release of Hoopvol in 1948.7

The Wheat Industry Control Board was established in 1935 to regulate the wheat industry in the wake of extremely poor-quality yields despite record production levels in 1935. Among the varieties available at the time, none were of bread-wheat quality. Following the establishment of the Wheat Industry Control Board, seven new varieties were released in the 1940s, with only two making an impact: Sonop (Kleintrou/Pelgrim) and Hoopvol (Kleintrou/Gluys Early/Spring Early) which became the most popular. Sonop was the first true bread wheat from the Elsenburg College of Agriculture.7 Between 1950 and 1959, four wheat varieties were released, with only two making an impact on the wheat industry: Daeraad (Unie52A/Kruger) and Dromedaris (Hope/Gluretty). Neethling's retirement and the resultant break in continuity, coupled with increased interest from his successors in terms of using wide crosses, is arguably the reason for the limited activity in terms of varietal releases during this period.

After taking over from Neethling as head of the Department of Genetics at Stellenbosch University in 1950, F.X. Laubscher introduced a completely new era in wheat breeding in the country. In 1952, he ushered in an era of extensive international cooperation with the introduction of the International Rust Nursery, in collaboration with Dr Bayless of the US Department of Agriculture. The new releases during the 1960s were based on completely new parents, combining good yield, excellent quality and disease resistance, thus surpassing the existing varieties at the time. One of the first varieties released during this period was Flameks (Mentana-Kenya-Supremo/Florence Aurore)7, with five new varieties released between 1960 and 1970, but without the same impact on the wheat industry. New avenues in local wheat breeding were opened following the singular success of short-strawed varieties from Borlaug and CIMMYT. In the now Northern Province of South Africa, St Clair Caporn initiated wheat breeding at Potchefstroom in 1918, while Pieper started winter wheat breeding in Bethlehem in 1954 for the Free State, and Schneider started irrigation-type spring wheat breeding at Losperfontein7 (in what is now the North West Province).

The discussion above indicates that wheat varietal improvements in the early years of wheat breeding were specific to the production area, with little or no movement from one area to another. This situation has changed over time, and wheat breeding companies - although they focus on wheat varieties specific to the different wheat-growing regions of the country - aim to produce varieties that are adaptable across the country. According to the World Bank21, there was little movement of genetic improvement technologies in the 1950s and 1960s, especially from the temperate North to the tropical South. Their report further argues that the focus on adapting improved varieties to subtropical and tropical regions since the 1960s has generated high payoffs and pro-poor impacts, which are expected to continue to grow with rapid advances in biological and informational sciences. Byerlee and Moya15 also found that the initial focus on CIMMYT wheat breeding activities was on specific environments (particularly irrigated areas in Mexico and South Asia), which were later expanded to rain-fed areas to incorporate resistance to diseases such as septoria (Septoria spp.) and stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) into CIMMYT germplasm. The further incidence of pests and diseases challenged CIMMYT to widen the focus on resistance to pests and diseases in different environments. Similarly, in South Africa, structural changes in the agricultural sector and the liberalisation of the wheat sector have also opened up the rapid growth of wheat breeding improvements that transcend beyond original regional production areas.

Establishment of ARC-SGI and wheat varietal improvements The ARC-SGI was established in 1975 as the Small Grains Centre. The SGI was aimed at harnessing the impact of the then-fragmented research efforts (especially small-grain breeding programmes in the then Cape, Transvaal and Orange Free State Provinces) into an organisation running along the lines of CIMMYT following the recommendation of Dr Borlaug to the Department of Agriculture.7,8,19 The Small Grains Centre was established as a research centre of the Highveld Region of the Department of Agriculture. The main objective was to help improve the production of small grains, including addressing production challenges, investigating new production possibilities and transferring information to strategic points. The SGI became an autonomous institute on 1 April 1995.

The Wheat Board, through motivations by Dr Jos de Kock, provided funding for a new Research Building in 1989 for the centre. De Villiers and Le Roux8 report that 90% of the infrastructure at the ARC-SGI was funded by the Wheat Board and indirectly by wheat farmers. In an effort to harness fragmented research efforts, the SGI, since its establishment in 1975, has managed to initiate the following: a national seed multiplication scheme, a national cultivar evaluation scheme and breeding of cultivars that were nationally coordinated from Bethlehem (SGI supplied at least 65% of all nationally bred cultivars up to 1996).8 The wheat variety improvements released by the ARC-SGI were started in 1975, and its contribution to wheat breeding remains very important to South Africa. The World Bank21 argues that in areas where markets fail and it is difficult to appropriate benefits, public investments are required in agricultural R&D, such as wheat varietal improvements.

Wheat varietal releases, sources and uses

The sources and uses of wheat varietal innovations are presented by geographical region/area and wheat growth habit. In addition, we discuss varietal improvements by wheat breeding structural/policy shifts: before the establishment of the ARC-SGI; after the establishment of ARC-SGI to deregulate the wheat sector in 1996; and post-deregulation (1997-2013).

Figure 2 shows the main wheat varietal improvement breeders for the period 1891 to 2013. Sensako has the highest number of varieties with 102 varieties since the mid-1960s. The ARC has the second highest with 51 varieties and Pannar has the third highest with 41 varieties. Monsanto follows with 20 varieties, while Professor J.H. Neethling has released 16 varieties - one of the highest number of individually released wheat varieties used to develop many South African varieties. Most of the wheat innovation in South Africa should be credited to him and his team. Analysis of the wheat varietal improvement breeders is taken further by organisation type: local private companies such as Sensako and Pannar; local public organisations such as the ARC-SGI and universities; local individuals; foreign private companies; and foreign public organisations (Figure 3). The results show that the local private sector, with a total of 171 wheat varieties, has the highest share of varieties released in South Africa for the period under study. Local public organisations, which include the ARC-SGI and universities, trail with 72 wheat varieties - less than half that of the local private sector. Results from Figures 2 and 3 clearly show that the private sector currently dominates wheat varietal improvements in the country. The current funding challenges in the public sector mean that the private sector will continue to dominate wheat varietal improvements. However, more effort would be required to support research that caters for all types of farmers, especially the emerging farmers who would want to grow wheat. This means that the public sector has a critical role to play in this area, in addition to releasing varietal innovations to large commercial farmers.

Figure 4 presents rates of varietal releases from 1880 to 2013 in South Africa. Figure 4 shows that wheat varietal innovations have evolved over time. The distinct period of interest in wheat varietal improvement history in South Africa includes pre-establishment of the Wheat Control Board in 1936; the period 1936-1976 (when the Small Grains Centre was established); 1976-1996 (when the Wheat Market was deregulated); and 1997 to the present. Prior to 1936, wheat varietal improvements and the release of varieties were driven by individual researchers and colleges of agriculture. When the Wheat Control Board was established in 1935, it started to promote research in wheat varietal innovations in the country. During these early years, funding from the Wheat Control Board was the main source of wheat varietal innovation research. The consolidation of research efforts from the then colleges of agriculture provided an important way of harnessing the synergies from the comparatively limited research capacity scattered across these colleges.19

The low rate of wheat varietal release in the late 1970s and early 1980s could have been driven by reduced government funding for all non-security departments in favour of increased demands for military support.19 The introduction of the Marketing of Agricultural Products Act in 1996 led to the dissolution of the Wheat Board, which affected the funding originally provided by the Board for wheat varietal improvements in the country. The establishment of the ARC in 1992 centralised all national agricultural research functions, including the mandate to serve historically segregated homeland areas.

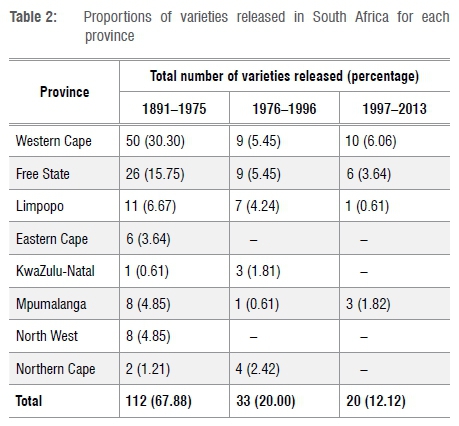

The varieties were also analysed by the geographical area for which they were released. Table 2 presents proportions of varieties released in South Africa for each geographical region. Initial wheat varietal breeding in South Africa focused on specific environments, which were expanded over time, especially since deregulation in 1996. Since the deregulation of the wheat sector, the ARC-SGI budget for wheat has steadily declined, reflecting reduced funding by the government for wheat varietal improvement.

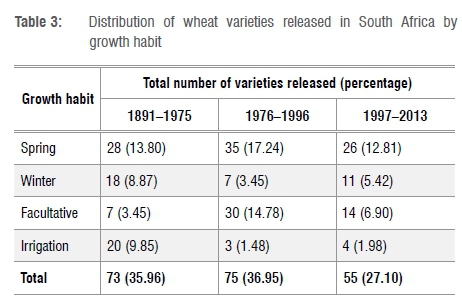

Table 3 presents the distribution of wheat varieties released by growth habit. In the period 1891-1975, most of the wheat varietal releases focused on spring (13.80%); irrigation (9.85%) and winter (8.87%) growth habits. Spring (17.24%) and facultative growth habits dominated wheat varietal improvements in the period 1976 and 1996. Since the deregulation of the wheat market in 1996, spring, winter and facultative growth habits have dominated wheat varietal improvement research in South Africa. Liebenberg and Pardey19 argue that initial agricultural R&D was decentralised and focused on specific environments and patterns of agricultural production. Specifically, the five agricultural colleges then focused their efforts on the main farming enterprises within their respective agro-ecological regions - for example, Elsenburg focused on winter grains. However, this situation has been greatly transformed over time, and public agricultural R&D is now more nationally centralised but has been experiencing a declining trend in recent years, at least since the deregulation of the wheat sector.

The analysis of wheat varietal releases was further divided into three distinct periods: the first comprising wheat varietal improvements prior to the establishment of the ARC-SGI; the second development from the establishment of the ARC-SGI to the deregulation period of the wheat sector; and the third period the post-deregulation period (1997 to 2013).

Appendix 1 of the supplementary material presents a summary of the wheat varieties released in the country, including information on their release years, breeders, last year of commercialisation, pedigrees, area suitable for planting the variety, and growth habits. The most popular ARC-SGI varieties identified for further analysis of the attribution of costs and benefits of wheat varietal improvements were Gariep, Eland and Duzi. These varieties performed well in the commercial market and were classified as some of the dominant national varieties by the South African Grain Laboratory. For example, Gariep was released in 1993 by SGI and has been one of the dominant varieties in Regions 23-25 based on the South African Grain Laboratory database of dominant varieties by region. Elands was released in 1998 by ARC-SGI and was dominant in Regions 21-26 for the period 2001-2016. This variety has remained dominant in the market for a long period. Duzi was released by ARC-SGI in 2004, and was a dominant ARC variety in Regions 30-35 for the period 2008-2015. The three varieties are of great interest because they are ARC varieties that have been dominant in the national wheat crop composition. Pedigree analysis of these varieties would be used to attribute the benefits of wheat varietal improvements among the ARC-SGI and other research agencies.

Smit et al.5 argue that the establishment of the Wheat Board through the Agricultural Marketing Act, Act 59 of 1968, and the subsequent deregulation of the wheat sector in 1996 after the enactment of the Marketing of Agricultural Products Act, Act 47 of 1996, have had a significant impact on both wheat research and the industry. For example, during the time of the Agricultural Marketing Act, the Wheat Board, in addition to regulating the wheat industry, also collected levies that were used to contribute to the funding of wheat research and varietal improvements. The deregulation of the wheat sector led to a shift in most research activities to a focus on factors aimed at lowering input costs and risks while increasing the profitability of wheat production.

Conclusions and recommendations

Wheat varietal innovations are important in agriculture, as they help to improve crop productivity, adaptability and resistance to pests and diseases, and also help to protect the environment. The main objective of this paper was to examine the historical evolution of wheat varietal improvements in the country, including the identification of popular varieties, and their history, sources and uses from 1891 to 2013.

About 501 varieties were released from wheat varietal innovations in South Africa between 1891 and 2013. From the 1800s, wheat varietal improvements in the country focused on addressing: adaptability to production area; yield potential and stability; and agronomic characteristics (e.g. tolerance to diseases, pests and aluminium toxicity). The main sources of wheat varietal improvements in South Africa are Sensako, ARC-SGI and Pannar. In terms of growth habits, most wheat varietal improvements have focused on spring and winter wheat varieties grown mostly under dryland conditions. Analysis by geographical area indicates that most of the wheat varieties released between 1891 and 2013 were for the Western Cape and Free State Provinces, which are the major wheat-producing areas in the country. Wheat varietal improvements in the early years of wheat breeding were decentralised and specific to the production area, with little or no movement from area to area. The structural changes that have occurred in the agricultural sector, particularly the establishment of the ARC-SGI and the deregulation of the wheat sector, have contributed to the effort to harness the impact of the existing fragmented research efforts, especially small-grain breeding programmes in the former Cape, Transvaal and Orange Free State Provinces.

Wheat breeding was initially driven by individual breeders and agricultural colleges. Since its establishment, Sensako has been the main source of wheat varieties, followed by the ARC-SGI and Pannar. The most popular varieties identified for further analysis, in terms of the attribution of costs and benefits of wheat varietal improvements, are Gariep, Elands and Duzi. The findings from this paper form the basis for a forthcoming paper focusing on the attribution of benefits and costs in terms of investment in wheat breeding in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant to the University of Pretoria's Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development. The paper is part of the PhD research by C.R.N. on: 'Biological Innovation in South African Agriculture: Economics of Wheat Varietal Change, 1950-2012' which was funded from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant.

Authors' contributions

C.R.N. conceptualised the article and compiled the first draft. J.K. made conceptual contributions and refined the article.

References

1. Atack J, Coclanis P Grantham G. Creating Abundance: Biological Innovation and American Agricultural Development - An appreciation and research agenda. Explor Econ Hist. 2009;46:160-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2008.11.001 [ Links ]

2. Lantican, MA, Dubin HJ, Morris ML. Impacts of international wheat breeding research in the developing world, 1988-2002. Mexico: CIMMYT; 2005. [ Links ]

3. South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). Wheat production guideline. Pretoria: Directorate Plant Production, DAFF; 2010. [ Links ]

4. Du Plessis AJ. The history of small-grains culture in South Africa. In: Annals of the University of Stellenbosch. Vol 8. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 1933. p. 1652-1752. [ Links ]

5. Smit HA, Tolmay VL, Barnard A, Jordaan JP Koekemoer FP Otto WM, et al. An overview of the context and scope of wheat (Triticum aestivum) research in South Africa from 1983 to 2008. S Afr J Plant Soil. 2010;27(1):81-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02571862.2010.10639973 [ Links ]

6. Chigeza G, Mashingaidze K, Shanahan P. Seed yield and associated trait improvements in sunflower cultivars over four decades of breeding in South Africa. Field Crops Res. 2012;130:46-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.01.015 [ Links ]

7. Van Niekerk H. Southern Africa wheat pool. In: Bonjean AP Angus WJ, editors. The world wheat book: The history of wheat breeding. Paris: Lavoisier Publishing; 2001. p. 923-936. [ Links ]

8. De Villiers PJT, Le Roux J. Small Grain Institute: 27 years of excellence. Bethlehem, South Africa: Small Grain Institute, Agricultural Research Council; 2003. [ Links ]

9. Stander CJ. The economics of cultivar improvement research in the South African wheat industry [MSc thesis]. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2010. [ Links ]

10. Trethowan RM, Hodson D, Braun HJ, Pfeiffer WH, Van Ginkel M. Wheat breeding environments. In: Lantican MA, Dubin HJ, Morris ML, editors. Impacts of international wheat breeding research in the developing world, 1988-2002. Mexico: CIMMYT; 2005. [ Links ]

11. Southern African Grain Laboratory (SAGL). Wheat crop quality report 2011/2012 season. Pretoria: SAGL; 2012. [ Links ]

12. South African Grain Information Services (SAGIS). Historical information 2015 [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] No date [cited 2015 Mar 06]. Available from: http://www.sagis.org.za

13. Purchase JL, Van Lill D. Directions in breeding for winter wheat yield and quality in South Africa from 1930 to 1990. Euphytica. 1995;82(1):79-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00028712 [ Links ]

14. Pannar. Wheat production guide. Greytown: Pannar; 2009. [ Links ]

15. Byerlee D, Moya FP Impacts of international wheat breeding research in the developing world, 1966-90. Mexico: CIMMYT; 1993. [ Links ]

16. Heisy PW, Lantican MA, Dubin HJ. Impacts of international wheat breeding research in the developing world, 1966-97. Mexico: CIMMYT; 2002. [ Links ]

17. Grace OM, Van Staden J. A horticultural history of Lachenalia (Hyacinthaceae). S Afr J Sci. 2003;99:526-531. [ Links ]

18. This P Lacombe T, Thomas MR. Historical origins and genetic diversity of wine grapes. Trends Genet. 2006;22(9):511-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.07.008 [ Links ]

19. Liebenberg F, Pardey PG. South African agricultural R&D: Policies and public institutions, 1880-2007. Agrekon. 2011;50:11-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2011.562681 [ Links ]

20. Neethling JH. Wheat varieties in South Africa: Their history and development until 1912. Sci Bull. 1932;108:41. [ Links ]

21. World Bank. World Development report 2008. Washington DC: World Bank; 2008. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Charity Nhemachena

cmudombi@yahoo.com

Received: 26 Jan. 2016

Revised: 14 June 2016

Accepted: 13 Sep. 2016

FUNDING: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation