Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Science

versión On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.112 no.5-6 Pretoria may./jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/20150223

RESEARCH ARTICLE

The composition of ambient and fresh biomass burning aerosols at a savannah site, South Africa

Minna AurelaI; Johan P BeukesII; Pieter van ZylII; Ville VakkariI; Kimmo TeiniläI; Sanna SaarikoskiI; Lauri LaaksoI, II

IFinnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland

IIUnit for Environmental Sciences and Management, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Atmospheric aerosols play a key role in climate change, and have adverse effects on human health. Given South Africa's status as a rapidly-developing country with increasing urbanisation and industrial growth, information on the quality of ambient air is important. In this study, the chemical composition of ambient particles and the particles in fresh biomass burning plumes were studied at a savannah environment in Botsalano, South Africa. The results showed that Botsalano was regularly affected by air masses that had passed over several large point sources. Air masses that had passed over the coal-fired Matimba power station in the Waterberg, or over the platinum group metal smelters in the western Bushveld Igneous Complex, contained high sulfate concentrations in the submicron ranges. These concentrations were 14 to 37 times higher compared with air masses that had passed only over rural areas. Because of the limited nature of this type of data in literature for the interior regions of southern Africa, our report serves as a valuable reference for future studies. In addition, our biomass burning study showed that potassium in the fresh smoke of burning savannah grass was likely to take the form of KCl. Clear differences were found in the ratios for potassium and levoglucosan in the smouldering and flaming phases. Our findings highlight the need for more comprehensive chamber experiments on various fuel types used in southern Africa, to confirm the ratio of important biomass burning tracer species that can be used in source apportionment studies in the future.

Keywords: air quality; chemical composition; rural environment; submicron particles; sulfate

Introduction

With regard to air quality, Africa is one of the least studied continents in the world. However, extensive aerosol measurements have been carried out in southern Africa within the framework of the SAFARI 92, SAFARI 2000 and EUCAARI campaigns.1,2 The first two campaigns focused mainly on the emissions of biomass burning and regional transport in the atmosphere. The EUCAARI campaign focused on understanding the interactions between climate and air pollution around the world. Several other air pollution measurement studies in South Africa have focused on nucleation events, trace gases and optical properties of aerosols.3-8 The chemistry of particles has been studied to a lesser extent.3-8

A few studies on the chemical characterisation or source apportionment of ambient aerosols have been conducted in Tanzania during the wet and dry seasons, and in various environments in Kenya.9-13 However, apart from the SAFARI 2000 campaign (which included multiple studies in southern Africa), few reports have been published that focus on the chemical characterisation of aerosols in South Africa.1,14 The most recent long-term measurements of aerosol chemical composition were conducted relatively close (approximately 100 km) to the JohannesburgPretoria megacity conurbation. In that study, different source regions were determined and the chemical characteristics of organics were investigated.15,16

The main objective of this paper is to contribute knowledge on the chemical composition of particles at a regional background location in North-West, a province of South Africa for which only sparse information on air quality is available. The chosen location is downwind of the Waterberg area on the dominant anti-cyclonic circulation route of air mass movement in this part of South Africa. The construction of a large new coal-fired power station, Medupi Power Station, in addition to the currently operational coal-fired power station in the Waterberg area, Matimba Power Station, highlights the need for such measurements to serve as a reference for future studies. Data on background aerosol chemical composition are also important because South Africa is a developing country with increasing urbanisation and industrial growth.

The sample site was chosen to represent a relatively clean background area with very little local pollution. The site gave us an opportunity to investigate how the chemical composition of aerosols changed depending on the origin of air masses. As far as we could assess, no other aerosol chemical composition studies have been published for this important area. Earlier studies have focused on the physical properties of aerosols at the site.17-19 In this study we concentrated mainly on submicron particles, because particles that originate from anthropogenic and natural wildfire combustion sources are typically smaller than 1 μm in aerodynamic size.

In addition to analysing the aerosol chemical composition of regional air masses, a biomass burning experiment was conducted onsite. This enabled us to investigate the chemical composition of aerosols originating from a fresh biomass burning plume.

Methodology

Site description and measurement periods

A mobile station for atmospheric measurement was deployed in the Botsalano game reserve in North-West Province, South Africa (25.541S, 25.754E, 1424 m AMSL).17,19 This setting can be considered a dry savannah regional background site, with no major local anthropogenic sources. Figure 1 shows the main large sources around the measurement site. Briefly, the sector from north to south, in an easterly direction, contains several large sources. Possibly, one of the largest regional pollution source areas might be the mining and pyro-metallurgical smelting activities in the western limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC).20-22

The ambient measurements reported in this paper were carried out in two short campaigns during 9-15 October 2007 (spring) and 30 January-5 February 2008 (summer). In total, 11 sets of impactor samples with a typical 24-hour sampling time were collected. The meteorological conditions of Botsalano during the campaigns are presented in Figure 2. The beginning of the spring campaign was slightly colder than the summer campaign; otherwise the seasons had similar temporal variation in temperatures. The relative humidity and temperature were on average 19% and 22% higher, respectively, during the summer campaign compared with the spring campaign. The summer and spring campaign represented typical seasons, according to the study by Laakso et al. (2008) at the same site in 2006-2007.17

In addition to the ambient samples, a small-scale biomass burning measurement experiment was performed. During the biomass burning experiment, organic materials consisting mainly of dry grass and branches collected upwind of the site were burned. The distance between the sampling equipment and the fire was approximately 50 m. Two samples were collected. The first sample was taken from the main plume, which was sampled for 44 min, and the second sample was taken over 124 min during the period when the fire intensity and fuel amount were lower.

Measurements

The samples were collected with a three-stage cascade impactor with aerodynamic cut-off diameters of 10 μm, 2.5 μm and 1 μm, followed by a backup filter (Dekati®PM10). The PM10 inlet was used for cutting off particles greater than 10 μm. The collection substrates were preheated quartz fibre filters (Tissuquartz, PALL). The sampling flow rate was 30 L/min and the sampling duration was approximately 24 h, except during the biomass burning experiment, when shorter sampling periods were utilised.

Chemical analysis

Organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) were analysed from a 1 cm2 sample punched out of the quartz fibre filters, using a thermal optical carbon analyser (TOA; Sunset Laboratory Inc. Tigard, OR, USA).

The instrument uses a two-phase thermal method to separate OC and EC (EUSAAR_1 and EUSAAR_2).23 Optical correction was performed to separate pyrolysed organic carbon from elemental carbon.

The sampled submicron particles (PM1) showed uniform deposition on the filters, but the larger fractions (particles >1 μm) were not uniformly spread. A previous study had shown that unevenly-spread samples yielded acceptable results when applying optical correction for impactor samples.24 Therefore, we analysed all the samples. The amount of gaseous OC collected on the filters was not measured and hence was not subtracted from the concentrations of OC. The overall uncertainty of the TOA method was estimated to be 10% for OC and 20% for EC in concentrations above the quantification limit.

The field blank concentrations of OC for the backup filters (PM1), calculated for a one-day sampling period, were just above the detection limit during both the spring (measured amount was 0.07 μg/m3) and summer (measured amount was 0.10 μg/m3) campaigns. For the impactor stages, the combined corresponding blank concentrations were 0.08 μg/m3 and 0.09 μg/m3 during the spring and summer campaigns respectively. The blank concentration of EC was below the detection limit for the impactor stages (0.02 μg/m3) and for the backup filters (0.07 μg/m3). The measured OC concentrations were multiplied by a factor of 1.6 to obtain an estimate for total particulate organic matter (POM) mass concentration.25

The remaining portions of the quartz filters were analysed with ion chromatography (IC) to determine selected ions, namely chloride (Cl-), nitrate (NO3-), sulfate (SO42-), oxalate, sodium (Na+), ammonium (NH4+), potassium (K+), magnesium (Mg2+) and calcium (Ca2+). The uncertainty of the IC analysis was estimated according to the analysis of standards as 5% to 10%, depending on the ion analysed. The field blank concentration of each ion in the backup and impactor-stage filters was 0.018 μg/m3 and 0.008 μg/m3 respectively, during both campaigns. The determination limit was below 0.002 μg/m3 for all the ions.

Concentrations of monosaccharide anhydrides (levoglucosan, galactosan and mannosan) collected on backup (PM1) filters were measured using an IC coupled to a quadrupole mass spectrometer.26 The blank concentration of monosaccharide anhydrides was below the determination limit (1 μg/L to 5 μg/L), which corresponded to 0.001 μg/m3 to 0.005 μg/m3 for a 24-hour sample.

Auxiliary data

Earlier publications17,19 presented detailed descriptions of measurements obtained at Botsalano using a Differential Mobility Particle Sizer (DMPS), consisting of a Vianna-type Differential Mobility Analyser and TSI model 3010 Condensation Particle Counter. The measures included meteorological parameters (temperature, pressure, relative humidity, precipitation, wind speed and wind direction), trace gas concentrations (SO2, NO/NOx, CO and O3) and submicron aerosol particle size distribution.

Total mass concentration of PM1 was not measured directly but was estimated from the DMPS size distribution, for the range 10 nm to 840 nm. For particles smaller than 840 nm, the particle number concentration of each DMPS size channel was converted to volume concentration (assuming spherical particles), multiplied by the estimated particle density, and summed to obtain the total mass concentration. The particle density value was calculated from the analysed chemical composition for each sample using an approach suggested by Saarnio et al.,27 and it varied from 1.38 to 1.75 g/cm3.

Air mass history

Air mass backward trajectories were calculated using the NOAA HYSPLIT backward trajectory model.28 The 96-hour backward air mass trajectories were calculated to arrive at every hour of sampling, with an arrival height of 100 m above the ground.

Results and discussion

Overall ambient air results

An overview of the meteorological pattern in Botsalano showed that the north-easterly wind direction had the highest frequency.19 This can be expected, as the meteorological pattern over the interior of South Africa is dominated by an anticyclonic circulation pattern.29 In addition, although Botsalano is a background site without significant local air pollution point sources, it is regularly affected by air masses that have passed over several large point sources. The Matimba coal-fired power station at Lephalale in the Waterberg, the silicon and platinum group metal (PGM) smelters near Polokwane, the PGM smelters in the Northam and Thabazimbi area, and the city of Gaborone are all situated on the dominant anticyclonic circulation path for air masses arriving at Botsalano. The mining and metallurgic activities in the western region, lying on the axis between the towns of Brits and Rustenburg (Bushveld Igneous Complex, BIC), are also likely to affect the site regularly.

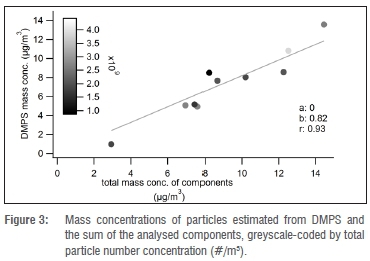

The PM1 mass concentrations calculated from the DMPS results varied between 1.4 μg/m3 and 21.5 μg/m3 (mean 11.3 μg/m3 ± 5.3 μg/m3). The total concentrations of all analysed components varied between 2.9 μg/m3 and 14.5 μg/m3 (mean 9.0 μg/m3 ± 3.2 μg/m3). The lowest concentrations showed the greatest difference between mass concentration (estimated from DMPS) and the sum of analysed components, as shown in Figure 3. The mean ratio between these two measures was 0.84 and they were strongly correlated (Pearson r = 0.93). Hence the analysed chemical components accounted for almost the entire total mass of the PM1 fraction. The lower mass concentration derived from DMPS was likely the result of a lower cut-off for particle size, compared with the PM sampler (840 nm vs 1 μm).

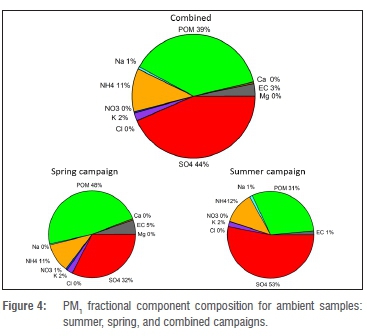

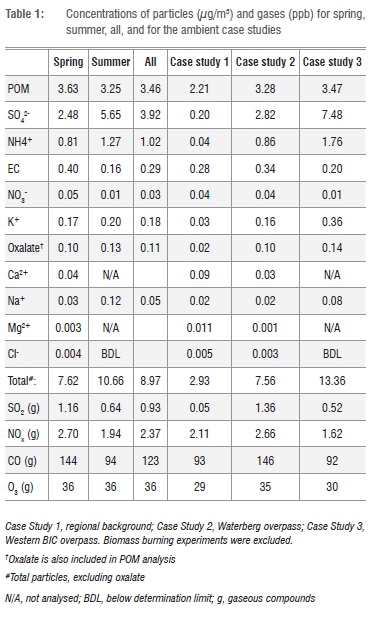

Figure 4 shows the PM1 fractional concentrations of the analysed components for the combined as well as the individual spring and summer campaigns. The mean values are shown in Table 1. For the combined results (spring and summer), sulfate had the highest individual component concentration at 44% (3.9 μg/m3 ± 2.3 μg/m3). POM was the second highest component at 39% (3.5 ± 0.6 μg/m3). Two main cations, ammonium and potassium, contributed 11% and 2% respectively. The rest of the components together contributed approximately 4%.

The equivalent ratio of sulfate to main cations for PM1 indicated that sulfuric acid was not neutralised totally. The average contribution of sulfate in Botsalano was higher than the amounts measured in similar campaigns lasting approximately one year in various environments in Europe and China, and at Welgegund near Potchefstroom in South Africa.15,30,31 However, at Welgegund a similar contribution has been noticed during the wet season, and similar findings have occurred in shorter campaigns at rural or remote sites in USA, Ireland and Japan.15,32 According to aerosol mass spectrometer (AMS) studies, the overall average contribution of submicron sulfate and organic matter around the world are 32% (range 10% to 67%) and 45% (range 18% to 70%) respectively.32

A comparison of the results from the spring and summer campaigns showed that POM was the dominant component during spring, whereas sulfate dominated in summer. Sulfate concentrations were clearly higher during summer than spring, whereas the POM concentrations did not vary significantly between the two seasons (Table 1). It is well known that oxidation of SO2 to sulfate occurs faster at higher relative humidity, as observed during summer, than in drier periods. The concentrations of SO2 and the ratio of SO2 to sulfate support this interpretation, with SO2 clearly being lower during the summer campaign compared with spring. This finding indicates a faster removal of SO2 in summer (Table 1).

Meteorological data for Botsalano, confirming the relative humidity levels, have previously been presented.17 It has also been suggested that ozone (O3) concentrations might be positively correlated with the sulfur conversion rate.33 However, in our study O3 concentration did not show a substantial difference between summer (range 17 ppb to 63 ppb) and spring (range 11 ppb to 58 ppb), although solar radiation in summer was on average 28% higher than in spring.

The EC level during the spring campaign was substantially higher than during the summer campaign (Table 1), which confirms the influence of combustion during spring. Although the concentration of levoglucosan, a biomass burning marker,34 remained relatively low throughout our study, it was substantially higher during spring than summer; the mean values were 0.010 μg/m3 in spring and 0.006 μg/m3 in summer. In addition, CO, which can be used as a gaseous tracer of combustion,35 showed similar trends, with means of 145 ppb and 92 ppb during the spring and summer campaigns respectively.

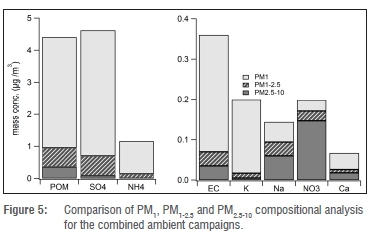

As previously mentioned, we found that the total concentration of the components analysed was a good approximation for the total PM1 mass, as calculated from DMPS data. Additionally, PM1 particle depositions on the filters were uniform, whereas the larger-size fractions were not. Because mass closure could not be performed for the PM1-2.5 and PM2.5-10 size fractions, we do not discuss these fractions individually in detail but only in comparison with the PM1 fraction. Figure 5 shows the analysed components for the various size fractions for the combined spring and summer ambient air sampling campaigns. From these data it is obvious that SO42-, POM, NH4+, EC and K+ were predominantly found in the PM1 size fraction, whereas NO3- occurred mostly in the coarser fractions. The size fraction analysis clearly indicates that the fine fraction (PM1) is dominated by water-soluble chemical compounds. Soil components, which were not analysed in this study, are likely to comprise the majority of the coarser fractions.

Ambient air case studies

In the previous paragraphs we established that the analysed chemical compounds were mainly found in the fine fraction (PM1). In addition, the mass balance could be calculated only for the PM1 fraction. Therefore, the following case studies focus mainly on the PM1 results.

Case study 1: Air masses that passed over the regional background

According to backward air mass trajectory analysis, there was one sampling day (9-10 October 2007) when the air masses arrived at Botsalano from the south-west. In this direction there are no large air pollution point sources, apart from the town of Mafikeng (population approximately 260 000), as indicated in Figure 6a.

Case study 2: Air masses that passed over the Waterberg

On three days during the sampling campaigns (11-12, 12-13 and 14-15 October 2007), air masses were likely to have been influenced by the coal-fired power station at Lephalale in the Waterberg, i.e. Matimba Power Station, without any influence from other large point sources (Figure 6b). The salience of this case study data is that at the time of writing, a second coal-fired power station - Medupi Power Station -had been commissioned for the Waterberg area. Matimba Power Station does not have equipment for removing sulfur and nitrogen gases from the emissions (de-SOx and de-NOx). By contrast, the newly-constructed Medupi Power Station will include such technology, although it is not yet clear if it will be implemented in the initial operations. The data in this case study could thus serve as a valuable reference for future studies in this region, to compare the concentrations of particles with and without NOx and SOx removal.

Case study 3: Air masses that passed over the western BIC

On two days during the sampling campaign (30 January-1 February 2008), the air masses arriving at Botsalano had passed directly over the two closest PGM smelters in the western BIC, situated east of Rustenburg (Figure 6c). These air masses were also likely to have travelled over the PGM and silicon smelters near Polokwane, but not over any other large air pollution point sources. The large air pollution point sources in the western BIC are mainly ferrochrome and PGM smelters as well as base metal refineries.20 The sampled air masses therefore do not represent all types of point sources that occur in the western BIC, but they do represent the PGM smelters occurring in this region.

Comparison of case studies

In Table 1 the comparative results for the three case studies identified are listed. From these results it is clear that the background air masses we sampled were substantially cleaner than the anthropogenically-influenced air masses. This was despite a possible influence of pollution from Mafikeng on the background air masses sampled. The total concentrations of the components measured in the PM1 fraction - which was also found to be a good approximation of the total PM1 mass, as indicated earlier -were as follows: 2.9 μg/m3 for the regional background, 7.6 μg/m3 for the Waterberg overpass, and 13.4 μg/m3 for the western BIC overpass.

The anthropogenic influence of the large point sources on the chemical composition of the PM1 fraction is especially apparent when sulfate compositions are considered. The regional background had a sulfate concentration of a mere 0.2 μg/m3, whereas air masses in the Waterberg overpass during spring and the Western BIC overpass during summer had levels of 2.8 μg/m3 and 7.5 μg/m3 respectively. During the Western BIC event, the sulfate-to-SO2 ratio was higher than on average during the summer campaign, indicating faster oxidation of SO2 or a longer transport time. The temperature and relative humidity during the event were similar to the averages, but the wind speed was lower than average. During the Waterberg event, the sulfate-to-SO2 ratio was similar to the spring average.

Samples from biomass burning experiments

During the ambient air sampling campaigns, no clear biomass burning plume could be identified, hence no ambient biomass burning plume case study is presented. The spring sampling season in mid-October was well past the peak activity of regional biomass burning, so we did not expect to find biomass-burning influences in the air masses. The highest levoglucosan concentration was 0.030 μg/m3, which was one order of magnitude lower than the background concentration (0.3 μg/m3) measured during the SAFARI 2000 campaign. The SAFARI 2000 campaign was conducted during a period of large-scale regional biomass combustion.35

Biomass burning is an important air pollution source in southern Africa, with implications for both air quality and climate change. To augment the ambient data already presented in this paper, data from the biomass burning experiment we conducted are presented in this section.

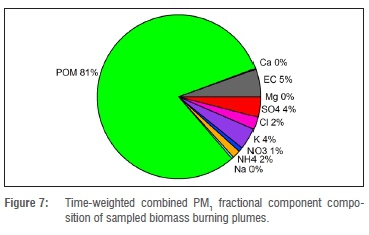

A fractional distribution graph of the time-weighted average for the various components analysed in the two biomass burning plume samples gives an overall indication of the relative importance of the components in fresh biomass burning plumes. These data are presented in Figure 7.

The table shows that POM was much higher than the other components in the PM1 fraction. We realise that some of the detected OC might have been gaseous OC, as the amount of gaseous OC was not measured. Previous studies have shown the amount of gaseous OC in ambient measurement to be between 6% and 19%.9,27,37 In our study, approximately a quarter of the analysed OC was vaporised during the first temperature step of the TOA analysis (T=75-200 °C), implying that these compounds were the most volatile. Some of these components might therefore have been gaseous OC absorbed or adsorbed into the filter substrate, or onto the particles collected on it. Despite this possibility, the dominance of POM in the PM1 fraction is evident.

The above finding is important, as it indicates that organic components released by biomass combustion during the dry season in southern Africa could play an important role during new particle formation and subsequent growth. This is in contrast to the wet season in southern Africa, when biogenic activities are mainly responsible for the release of organic components. The situation in southern Africa is therefore completely different from European and North American conditions, where biogenic activity is the main source of atmospheric organic compounds - at least in rural areas. The chemical and physical characteristics in the atmosphere are therefore likely to differ substantially across these continents.

The dominant contribution of POM to PM1 aerosol from biomass burning smoke supports the findings presented in a recent paper.38 The relevant study had focused on the effect of biomass burning plumes on the formation and growth of ambient atmospheric aerosols in southern Africa, based on long-term data.38 Apart from the high (81%) POM contribution to PM1 (Figure 7), further differences between biomass burning plume samples and other samples were the concentrations or the contributions of monosaccharide anhydrides, oxalate and potassium, which can be attributed as biomass burning tracers.36 Their concentrations increased substantially during the biomass burning event, compared with the ambient samples. The concentration of submicron oxalate during the biomass burning event increased almost four-fold compared with the average of the ambient samples. However, the relative contribution of oxalate to POM (0.1%) was smaller than the oxalate contribution to all the ambient samples combined (2.7%). The contribution of K+ in PM1 during biomass burning (4% to 5%) was double that of the ambient samples (2%).

The ratios of monosaccharide anhydrides give information on the biomass burning material. The ratios of levoglucosan to mannosan and levoglucosan to galactosan in the first plume were 17.1 and 14.0 respectively; in the second plume, the ratios were 16.4 and 17.4 respectively. These ratios were quite similar to values measured in laboratory experiments in which savannah grass with acacia wood was burned (levoglucosan to mannosan ratio of 21.7, and levoglucosan to galactosan ratio of 15.2).39 It has been reported that fresh smoke of savannah grass contains potassium chloride (KCl) particles, whereas aged smoke contains potassium sulfate (K2SO4) and potassium nitrate (KNO3).36,40 In our study, Cl- was the most abundant anion (3%) in the first plume, followed by sulfate (2%) and nitrate (1%). These results indicate that most of the K+ was probably present as KCl. The calculation of equivalent ratios showed an excess of K+ compared with Cl-, SO42-and NO3-. However, if SO42- was assumed to react first with NH4+, there was no excess sulfate left for K+. The additional K+ might therefore be present as carbonaceous material such as K2CO3, which was detected in an earlier biomass burning study in southern Africa.41

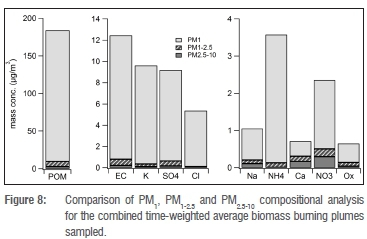

Because components analysed in the coarse fractions (PM1-2.5 and PM2.5-10) are unlikely to approach mass closure, we present our results only in a comparative manner to the PM1 results (Figure 8). The dominance of the PM1 fraction in the overall PM10 chemical composition in fresh biomass burning plumes is evident from these results. More than 90% of the POM, EC, K+, Cl-, SO42- and NH4+ ammonium were in a PM1 fraction. The NO3-, Na+ and oxalate were mainly in the PM1 fraction (62% to 83%), whereas at least 50% of Ca2+ was in the PM1 fraction.

Conclusion

Size-segregated aerosol samples were collected using a three-stage impactor with backup filter at a relatively clean savannah environment at Botsalano Game Reserve in South Africa. The backup filter collected particles smaller than 1 μm. Other size ranges were >10 μm, 2.5-10 μm and 1-2.5 um. Two campaigns were performed, one in spring (October 2007) and the other in summer (January-February 2008). In total throughout the entire study period, 11 sets of impactor samples were collected. In addition to these ambient measurements, a biomass burning experiment was performed to determine the chemical composition of fresh biomass burning fire plumes. Organic and elemental carbon, selected ions and monosaccharide anhydrides (e.g. levoglucosan) were analysed. These components essentially comprised the total mass of the PM1 fraction.

Results of the ambient air mass analyses indicated that sulfate, organic carbon, ammonium, elemental carbon and potassium were mostly associated with fine particles (PM1). Other components (sodium, chloride, nitrate and oxalate) were divided into fine and coarse fractions, but their concentrations were very small. POM was the dominant component during spring, whereas sulfate dominated in summer. Some indications of differing oxidation rates for SO2 were found between the seasons, explaining the higher sulfate concentrations during the summer campaign. Substantially higher elemental carbon concentrations in spring indicated the occurrence of more combusting processes compared with the summer campaign.

Although Botsalano is a background site, it is regularly affected by air masses that have passed over several large point sources. The anthropogenic influence of these large point sources on the chemical composition of the PM1 fraction was apparent, especially when the sulfate composition was considered. Air masses that passed over the coal-fired power station in Waterberg or the PMG smelter increased the sulfate concentration by 14 or 37 times compared with background air. Characterisation of air masses that had passed over the Waterberg area was especially important, because an additional large coal-fired power station was being commissioned at the time of writing (2015). The data presented here can be compared with the findings of similar studies, after the new coal-fired power station comes online. Comparisons can also be made between our data and those obtained after the de-SOx and de-NOx technologies of the new power station become operational. Such comparisons would help to assess the impact of large industrial developments in this region of South Africa.

The biomass burning study confirmed that potassium in fresh biomass plumes probably takes the form of KCl, for the most part, rather than K2SO4 and KNO3. Clear differences were also found in the ratios of potassium and levoglucosan in the smouldering and flaming phases. Our data highlight the need for more comprehensive chamber-type experiments on the major fuel types, to confirm the ratio of important biomass burning tracer species. Such information can, in future, be used to better quantify the contribution of biomass burning in source apportionment studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support received from the Academy of Finland under the project Air Pollution in Southern Africa (APSA) (project number 117505). We also thank the Head of the Botsalano Game Reserve, M. Khukhela, and the game reserve employees, for their kind and invaluable help during our measurements. In addition we are grateful to M. Jokinen and E. Sjöberg for their help in organising the project.

Authors' contributions

M.A. was the main investigator and wrote the primary manuscript; the study formed part of her PhD study, with S.S. as the degree supervisor. J.PB revised the manuscript, V.V. and L.L. maintained the research station and helped to generate the data, P.v.Z. made conceptual contributions, and K.T. assisted with chemical analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Swap RJ, Annegarn HJ, Suttles JT, King MD, Platnick S, Privette JL, et al. Africa burning: A thematic analysis of the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000). J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D13):8465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2003JD003747 [ Links ]

2. Kulmala M, Asmi A, Lappalainen HK, Baltensperger U, Brenguier J-L, Facchini MC, et al. General overview: European Integrated project on Aerosol Cloud Climate and Air Quality interactions (EUCAARI) - integrating aerosol research from nano to global scales. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:13061-13143. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-13061-2011 [ Links ]

3. Laakso L, Merikanto J, Vakkari V Laakso H, Kulmala M, Molefe M, et al. Boundary layer nucleation as a source of new CCN in savannah environment. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:1957-1972. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1957-2013 [ Links ]

4. Laakso L, Vakkari V Virkkula A, Laakso H, Backman J, Kulmala M, et al. South African EUCAARI measurements: seasonal variation of trace gases and aerosol optical properties. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:1847-1864. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-1847-2012 [ Links ]

5. Lourens AS, Beukes JP Van Zyl PG, Fourie GD, Burger JW, Pienaar JJ, et al. Spatial and temporal assessment of gaseous pollutants in the Highveld of South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2011;107(1/2):269-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v107i1/2.269 [ Links ]

6. Martins J, Dhammapala R, Lauchmann G, Galy-Lacaux C, Pienaar J. Long-term measurements of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia, nitric acid and ozone in southern Africa using passive samplers. S Afr J Sci. 2007;103:336-342. [ Links ]

7. Hirsikko A, Vakkari V Tiitta P Manninen HE, Gagné S, Laakso H, et al. Characterisation of sub-micron particle number concentrations and formation events in the western Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:3951-3967. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-3951-2012 [ Links ]

8. Hirsikko A. Vakkari V Tiitta P Hatakka J, Kerminen VM, Sundström AM, et al. Multiple daytime nucleation events in semi-clean savannah and industrial environments in South Africa: analysis based on observations. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:5523-5532. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-5523-2013 [ Links ]

9. Mkoma S, Chi X, Maenhaut W. Characterization of carbonaceous materials in PM2.5 and PM10 size fractions in Morogoro, Tanzania, during 2006 wet season campaign. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 2010;B268:1665-1670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2010.03.001 [ Links ]

10. Mkoma S, Wang W, Maenhaut W. Seasonal variation of water-soluble inorganic species in the coarse and fine atmospheric aerosols at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 2009;B267:2897-2902. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.06.099 [ Links ]

11. Mkoma S, Maenhaut W, Chi X, Wang W, Raes N. Characterisation of PM10 atmospheric aerosols for the wet season 2005 at two sites in East Africa. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:631-639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.10.008 [ Links ]

12. Mkoma S, Maenhaut W, Chi X, Wang W, Raes N. Chemical composition and mass closure for PM10 aerosols during the 2005 dry season at a rural site in Morogoro, Tanzania. Xray Spectrom. 2009;38:293-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/xrs.1179 [ Links ]

13. Gaita SM, Boman J, Gatari MJ, Pettersson JBC, Janhäll S. Source apportionment and seasonal variation of PM2.5 in a Sub-Saharan African city: Nairobi, Kenya. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:9977-9991. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9977-2014 [ Links ]

14. Maenhaut W, Schwarz J, Cafmeyer J, Annegarn H. Study of elemental mass size distributions at Skukuza, South Africa, during the SAFARI 2000 dry season campaign. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 2002;189:254-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0168-583X(01)01053-9 [ Links ]

15. Tiitta P, Vakkari V, Croteau P, Beukes JP, Van Zyl PK, Josipovic M, et al. Chemical composition, main sources and temporal variability of PM1 aerosols in southern African grassland. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:1909-1927. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-1909-2014 [ Links ]

16. Booyens W, Van Zyl PG, Beukes JP Ruiz-Jimenez J, Kopperi M, Riekkola M-L et al. Size-resolved characterisation of organic compounds in atmospheric aerosols collected at Welgegund, South Africa, J Atmos Chem. 2015;72:43-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10874-015-9304-6 [ Links ]

17. Laakso L, Laakso H, Aalto PP, Keronen P, Petäjä T, Nieminen T, et al. Basic characteristics of atmospheric particles, trace gases and meteorology in a relatively clean southern African savannah environment. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8:4823-1839. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-4823-2008 [ Links ]

18. Vakkari V, Beukes JP, Laakso H, Mabaso D, Pienaar JJ, Kulmala M, et al. Long-term observations of aerosol size distributions in semi-clean and polluted savannah in South Africa. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:1751-1770. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1751-2013 [ Links ]

19. Vakkari V, Laakso H, Kulmala M, Laaksonen A, Mabaso D, Molefe M, et al. New particle formation events in semi-clean South African savannah. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:3333-3346. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-3333-2011 [ Links ]

20. Hirsikko A, Vakkari V, Tiitta P, Manninen HE, Gagné S, Laakso H, et al. Characterisation of sub-micron particle number concentrations and formation events in the western Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:3951-3967. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-3951-2012 [ Links ]

21. Venter AD, Vakkari V, Beukes JP, Van Zyl PG, Laakso H, Mabaso D, et al. An air quality assessment in the industrialised western Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2012;108(9/10):1059-1068. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v108i9/10.1059 [ Links ]

22. Lourens ASM, Butler TM, Beukes JP, Van Zyl PG, Beirle S, Wagner TK, et al. Re-evaluating the NO hotspot over the South African Highveld. S Afr J Sci. 2012;108(11/12):1146-1152. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v108i11/12.1146 [ Links ]

23. Cavalli F, Viana M, Yttri KE, Genberg J, Putaud J-P. Toward a standardised thermal-optical protocol for measuring atmospheric organic and elemental carbon: the EUSAAR protocol. Atmos Meas Tech. 2013;3:79-89. [ Links ]

24. Jaffrezo J-L, Aymoz G, Cozic J. Size distribution of EC and OC in the aerosol of Alpine valleys during summer and winter. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5:2915-2925. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-2915-2005 [ Links ]

25. Turpin B, Lim H-J. Species Contributions to PM2.5 mass concentrations: revisiting common assumptions for estimating organic mass. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2001;35:602-610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02786820119445 [ Links ]

26. Saarnio K, Teinilä K, Aurela M, Timonen H, Hillamo R. High-performance anion-exchange chromatography-mass spectrometry method for determination of levoglucosan, mannosan, and galactosan in atmospheric fine particulate matter. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398:2253-2264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00216-010-4151-4 [ Links ]

27. Saarnio K, Aurela M, Timonen H, Saarikoski S, Teinilä K, Mäkelä T, et al. Chemical composition of fine particles in fresh smoke plumes from boreal wild-land fires in Europe. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:2527-2542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.03.010 [ Links ]

28. Draxler RR, Rolph GD. 2003 HYSPLIT (HYbrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) Model. Available from: http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html. [ Links ]

29. Tyson PD, Garstang M, Swap R. Large-scale recirculation of air over Southern Africa. J Appl Meteorol. 1996;35:2218-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1996)035<2218:LSROAO>2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

30. Putaud JP Raes F, Van Dingenen R, Brüggemann E, Facchini MC, Decesari S, et al. A European aerosol phenomenology - 2: Chemical characteristics of particulate matter at kerbside, urban, rural and background sites in Europe. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:2579-2595. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.01.041 [ Links ]

31. He K, Zhao Q, Ma Y Duan F, Yang F, Shi Z, Chen G. Spatial and seasonal variability of PM25 acidity at two Chinese megacities: Insights into the formation of secondary inorganic aerosols. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:1377-1395. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-1377-2012 [ Links ]

32. Zhang Q, Jimenez JL, Canagaratna MR, Allan JD, Coe H, Ulbrich I, et al. Ubiquity and dominance of oxygenated species in organic aerosols in anthropogenically-influenced northern hemisphere midlatitudes. Geophys Res Lett. 2007;34:L13801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2007GL029979 [ Links ]

33. Khoder MI. Atmospheric conversion of sulfur dioxide to particulate sulfate and nitrogen dioxide to particulate nitrate and gaseous nitric acid in an urban area. Chemosphere. 2002;49:675-684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00391-0 [ Links ]

34. Simoneit BRT, Schauer JJ, Nolte CG, Oros DR, Elias VO, Fraser MP et al. Levoglucosan, a tracer for cellulose in biomass burning and atmospheric particles. Atmos Environ. 1999;33:173-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(98)00145-9 [ Links ]

35. Cabada J, Pandis S, Subramanian R, Robinson A, Polidori A, Turpin B. Estimating the Secondary Organic Aerosol Contribution to PM2.5 Using the EC Tracer Method. Aerosol Sci Tech. 2004;38(S1):140-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02786820390229084 [ Links ]

36. Gao S, Hegg DA, Hobbs PV, Kirchstetter TW, Magi BI, Sadilek M. Water-soluble organic components in aerosols associated with savanna fires in southern Africa: Identification, evolution, and distribution. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D13): 8491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002324 [ Links ]

37. Sillanpää M, Frey A, Hillamo R., Pennanen AS, Salonen RO. Organic, elemental and inorganic carbon in particulate matter of six urban environments in Europe. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5:2869-2879. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-2869-2005 [ Links ]

38. Vakkari V Kerminen V-M, Beukes JP Tiitta P Van Zyl P Josipovic M, et al. Rapid changes in biomass burning aerosols by atmospheric oxidation. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41:2644-2651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059396 [ Links ]

39. linuma Y Brüggemann E, Gnauk T, Müller K, Andreae MO, Helas G, et al. Source characterization of biomass burning particles: The combustion of selected European conifers, African hardwood, savanna grass, and German and Indonesian peat. J Geophys Res. 2007;112:D08209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007120 [ Links ]

40. Li J, Pósfai M, Hobbs P Buseck P. Individual aerosol particles from biomass burning in southern Africa: 2, Compositions and aging of inorganic particles. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D13):8484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002310 [ Links ]

41. Pósfai M, Simonics R, Li J, Hobbs PV Buseck PR. Individual aerosol particles from biomass burning in southern Africa: 1. Compositions and size distributions of carbonaceous particles. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D13):8483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002291 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Minna Aurela

Finnish Meteorological Institute

Erik Palmenin aukio 1

FIN-00560 Helsinki, Finland

Email: Minna.Aurela@fmi.fi

Received: 10 June 2015

Revised: 09 Oct. 2015

Accepted: 01 Dec. 2015