Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Science

versão On-line ISSN 1996-7489

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.111 no.11-12 Pretoria Nov./Dez. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2015/20140435

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Exploring the connections between green economy and informal economy in South Africa

Suzanne SmitI; Josephine K. MusangoI, II

ISchool of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

IICentre for Renewable Energy Studies, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The notion of an inclusive green economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication requires an approach that engages with the informal economy. However, the informal economy is generally ignored or undervalued in discussions on the green economy. This paper set out to bolster this argument by identifying the ways in which the green economy and the informal economy may be connected by establishing the extent to which policies and plans relating to green economy connect with the informal economy, and recognising several informal green activities. The barriers and opportunities for connecting the two spheres were also explored as well as possible ways in which such activities may be supported at different levels of organisation. In the case of South Africa, many informal green activities that contribute to sustainable livelihoods are recognised. However, issues pertaining to procedure, process and participation hinder the transition to a truly inclusive green economy.

Keywords: informal green jobs; sustainable livelihoods; second economy; sustainable development

Introduction

The South African government recognises a green economy as providing potential to transition to a low carbon economy, resource efficiency and the creation of pro-poor jobs.1,2 Generally, the concept of green economy is not new but a re-emerging one, and it is gaining prominence in international and national policy debates.35 The United Nations Environment Programme4 defines the green economy 'as one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities'. According to Death6, there are four green economy discourses that are theoretically distinct, but which in practice tend to overlap. These discourses are green revolution, green transformation, green resilience and green growth. Some studies in the South African context have focused on only one of these discourses. For instance, Resnick et al.5 focused on green growth and utilised four case studies in Southern Africa; Swilling et al.7 specified some studies that could be classified in each of the four different discourses.

Death6 argues that these four discourses are characteristic of South Africa and that 'large-scale structural transformation' will be required to orient the country towards green economy. While Death's6 view is agreeable to many, Swilling et al.7 differ with some arguments and contend that: (1) green transformation in a developing country would require some element of growth; (2) green economy should be part of wider sustainability transition that is not about decarbonisation and resource efficiency, but also about redistributive measures that reduce inequality and poverty.

At Rio+20, the green economy concept was further expanded to represent the social dimension of sustainable development leading to the notion of an inclusive green economy8 as taking place 'in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication'9. The implication for an inclusive green economy is that both the formal and the informal economy need to be prioritised in green economy discussions.

It is thus within the context of finding redistributive measures as argued in Swilling et al.7 and as representing the social dimension as per the Rio+20 outcome document, that this paper relates to, and argues the need for connecting the green economy with the informal economy.

There are a number of definitions pertaining to the informal economy that impact on data collection and measurement of its size and monetary value.10-13 The following definition by the International Labour Organisation14, is preferred as it recognises the heterogeneity of activities occurring in the informal economy that cut across different sectors. Accordingly, the informal economy is recognised as:

...economic activities by workers and economic units that are - in law or in practice - not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements. Their activities are not included in the law, which means that they are operating outside the formal reach of the law; or they are not covered in practice, which means that - although they are operating within the formal reach of the law, the law is not applied or not enforced; or the law discourages compliance because it is inappropriate, burdensome, or imposes excessive costs.14

Literature pertaining to the green economy and the informal economy indicate that the latter is generally undervalued or ignored in discussions on the former.15,16 It is further argued that the informal economy 'offers both opportunities and lessons on resilience and innovation' and that connecting the two is imperative in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication.15

To the best of our knowledge, there are limited theoretical and empirical studies that connect the green economy with the informal economy. Smit and Musango's15 study seems to be among the initial studies providing such an understanding in the South African context. In their paper, Smit and Musango15 critically review the macro perspective and understanding of the green economy landscape, and how these relate to the reality of a green economy in South Africa. They deepen this understanding by further tracing various perspectives and approaches to 'managing' the informal economy and identify the role and value of the informal economy for sustainable development and a green economy.

Based on their critical review, Smit and Musango15 argue that an inclusive green economy requires the conceptualisation and implementation of a green economy that engages with the informal economy. By overlooking the informal sector, policy and planning initiatives are not fully engaged with the real everyday experiences and activities of those living in the survivalist economy, leading to a narrow conception of what a green and inclusive economy may be. The informal economy, however, is a very real phenomenon that warrants greater inclusion and consideration in planning for sustainable development.

We set out to explore the range of possible connections between the green economy and the informal economy within the context of a developing country, taking South Africa as a case. Although the informal economy is markedly smaller in South Africa than in the rest of Africa,17 it is no less valuable to an expanded and contextually relevant green economy policy environment. The need to engage the informal economy is especially pressing given that South Africa has to consider transitioning towards a low carbon path whilst curbing the high levels of inequality and unemployment.18,19 Thus, in this paper, the key questions explored, in connecting the green economy to the informal economy are: (1) To what extent does green economy policies and plans connect with the informal economy? (2) What 'green' activities are taking place within the informal economy that contribute to sustainable livelihoods? (3) How can these activities be supported and developed to expand the current planning and policy environment?

Methods and tools

This paper was informed by grounded theory methodology; we used multiple methods, thereby allowing for a more holistic understanding of the problem. The initial literature analysis by Smit and Musango15 indicated a gap in terms of research that connected the informal economy with the green economy, leading to the proposition that a new theory would have to emerge from the study itself. In this way, the study lent itself to the grounded theory methodology. Data collection and data analysis tools utilised are discussed in the sections that follow. A detailed step-by-step process can be found in Smit20.

Content analysis

The content analysis involved identifying and analysing a set of fourteen national policies and plans in South Africa that relate to the green economy in order to establish the extent of informal economy coverage and to identify the informal green activities therein. According to Babbie21|p-309), content analysis 'is particularly well suited to the study of communications' in order to establish what is said, to whom, why, how and with what effect. In the case of policies and plans relating to the green economy in South Africa, the aim was to ascertain the level and quality of engagement with the informal economy. The units of analysis were appropriately identified as those documents that guide national, regional and local interventions for a green economy as recognised by Montmasson-Claire22, Musango et al.2 and Sustainlabour, COSaTU and TIPS23. The sampling method involved reducing the scope as per the limitations of the study to appropriate national policies and plans created in the period 2008-2013. These included the following:

-

Ten Year Innovation Plan 2008-201824

-

Framework for South Africa's response to the international economic crisis25

-

Medium Term Strategic Framework 2009-201426

-

Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) 201 0-2 0 3 027

-

National Skills Development Strategy III 2011-201 628

-

National Climate Change Response White Paper29

-

National Waste Management Strategy30

-

New Growth Path, Green Economy Accord31

-

National Strategy for Sustainable Development and Action Plan (NSSD) 2011-201432

-

National Development Plan (NDP) 2 0 3 033

-

Draft 2012 Integrated Energy Plan34

-

Bioeconomy Strategy35

-

National Water Resource Strategy36

-

Industrial Policy Action Plan 201437

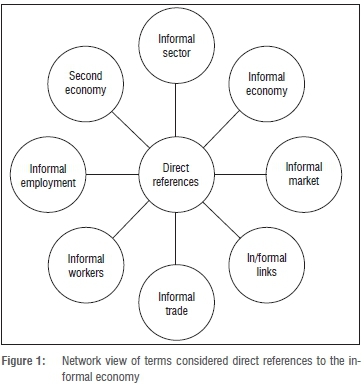

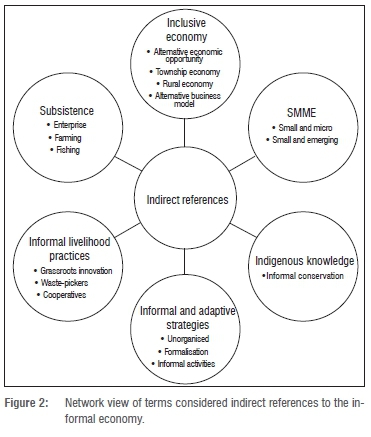

In order to extract the relevant data, each key document was evaluated on the number of times that particular terms occurred throughout each document, referred to as evaluating the manifest content.21 These terms were initially coded as relating to direct references to the informal economy (Figure 1); however, through the coding process, it became apparent that it was necessary to consider a wider formulation of the concept of informal economy based on its defining characteristics. Such occurrences were coded as indirect references to the informal economy (Figure 2). The resulting data were then coded and analysed using ATLAS.ti.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts in the field of the informal economy as well as those involved in facilitating, planning or implementing green economy policies, plans, projects or activities.

Initially, interviewees were identified through networking opportunities at green economy meetings or workshops and subsequent candidates were identified from mailing lists obtained from the organisers of some of the events. The sampling method therefore involved nonprobability sampling, utilising purposive or judgemental sampling in combination with snowball sampling.

A list of pertinent open-ended and closed questions was formulated and posed, yet the semi-structured nature of the questions allowed for deeper probing and exploration (these questions are available in Appendix 1 as online supplementary material). The responses to these questions were recorded and coded. The coding process was both inductive and deductive. Inductive coding related to codes and concepts as emerging directly from the interview data, whereas deductive coding related to codes and concepts that emerged from the survey results, content analysis and observations and which were then searched for reiteratively within the interview data.

Surveys

An online questionnaire was circulated to a number of potential informants ranging from academics, to NGO practitioners and national, provincial and municipal level government officials (the questionnaire is available in Appendix 2 as online supplementary material). The questionnaire was designed to extract data relevant to each of the three research questions and therefore consisted of multiple question types. A number of questions lent themselves to quantitative data analysis through descriptive statistics, such as frequency tables and bar graphs, whilst the open-ended questions were considered to constitute qualitative data requiring computer-assisted qualitative data analysis using ATLAS.ti and were presented either as matrices or, where appropriate, as direct quotations.

Respondents were also asked to rate the level of engagement between a list of policies and plans relating to the green economy and the informal economy on a scale including Very High, High, Moderate, Low and Non-existent. Participants were asked to only rate those policies that they were familiar with and were given the option of choosing 'Not Applicable' in order to indicate the policies that they were unfamiliar with. The valid responses per policy were presented as a frequency table. The valid response count was calculated by deducting the number of 'Not Applicable' responses from the response count per policy.

Direct observation

Within this study, observations were obtained with different levels of participation, including attendance of four green economy related workshops or meetings ranging from national to local level. Direct observations were also made of green activities taking place in two informal settlements, thereby triangulating data from the interviews and questionnaires with observations from the field.

Results and discussion

Extent of engagement with the informal economy

Policies and plans relating to the green economy 'set the tone', so to speak, for understanding the extent of engagement between the green economy and the informal economy. Table 1 represents the results from the content analysis. The categories 'Direct references' and 'Indirect references' were considered to be indicative of the level and quality of engagement between a particular policy or plan and the informal economy.

Based on the combined direct and indirect references to the informal economy, the policies and plans were ranked in terms of their comparative level of engagement. The results indicate the National Development Plan33 as the plan with the most overall references and the Integrated Resource Plan27 as the plan with the fewest references to the informal economy.

Table 1 further illustrates that there are significantly fewer direct than indirect references to the informal economy, which may be indicative of a lack of conceptual or definitional understanding of what the informal economy is. Alternatively, it may signal that the informal economy is not recognised as having value within the green economy. For example, the Green Economy Accord31, ranked sixth, made only one direct reference to the informal economy, even though the Economic Development Department has a mandate in terms of developing the 'second economy'.

Assuming that direct references are preferable to indirect references in terms of recognising and engaging with the informal economy, several policies were found to be problematic, in particular the National Strategy for Sustainable Development32, which ranked eighth yet aims to build sustainable communities and work towards a green economy. The Ten-Year Innovation Plan24 was ranked 11th and made several indirect references, yet all of the references pertained to indigenous knowledge systems only, and therefore this plan does not explore other possibilities within the informal economy.

There also seems to be an overall disconnect between policies and plans that drive the green economy and the informal economy. The low level of engagement is evidenced by the lack of overall reference to the informal economy (that is either direct or indirect). In contrast to the majority of the policies and plans, however, the National Development Plan33 ranked first and stands out as recognising and engaging with the informal economy. The quality of its engagement is also evidenced by its identification of challenges and opportunities relating to the informal economy as well as its recognition of the need for a more inclusive economy.

In order to triangulate the findings from the content analysis process, participants in the online questionnaire were asked to rate a set of policies and plans in terms of each policy's engagement with the informal economy (Table 2). Respondents were asked to rate only those policies that they were familiar with. The valid response count therefore took into account the number of people who responded to each question less those who were unfamiliar with the particular policy. The results therefore pertain to the rating by respondents who were familiar with each policy.

From Table 2, the following observations are pertinent. The National Development Plan33, which most participants (12 out of 14) were familiar with, was rated by the majority of respondents (8 out of 12, or 67%) as having a 'High'' (25%) to 'Very High' (42%) level of engagement with the informal economy. This finding supports the results from the content analysis, which found the National Development Plan33 to have the highest number of direct and indirect references to the informal economy as compared to the other policies in the sample. Data from the semi-structured interviews, however, rate the National Development Plan33 at a moderate level of engagement. Interviewee 1 explained that on first reading, the National Development Plan33 seemed to have little engagement with the informal economy but on more detailed reading and considering more 'holistic comments', the level of engagement was more moderate. Interviewee 1 also indicated that the National Development Plan33 seemed to designate responsibility for the informal economy at local government level.

A conflicting result, however, relates to the National Strategy for Sustainable Development32, which was found in the content analysis to have a surprisingly low number of references to the informal economy, whereas the survey indicated that more than half of the respondents (7 out of 11 or 63%) rated it as having 'High' (36%) to 'Very High' (27%) engagement.

In terms of the Integrated Resource Plan27, the content analysis indicated that there were no references to the informal economy, and although more respondents (5 out of 11 or 45%) rated it as having 'Low' (36%) to 'Non-existent'' (9%) engagement, there were some respondents (4 out of 11 or 36%) who considered it to have 'High' (27%) to 'Very High' (9%) engagement.

The Green Economy Accord31 was rated by more than half of the survey respondents (7 out of 12 or 58%) as having 'High' (33%) to 'Very High' (25%) engagement. This accord was rated 'Moderate' by 25% of the respondents and only 16% rated it as 'Low' (8%) to 'Non-existent' (8%). In comparison, the content analysis indicated that the Accord made only 13 overall references to the informal economy, which placed it sixth in the overall ranking of policies. This discrepancy in the comparison between the respondents' perception and the results from the content analysis may be indicative of the divide between the expectations and the reality of an inclusive green economy.

Green activities in the informal economy

From the second question, we aimed to identify 'green' activities taking place in the informal economy and to gauge the range of possible connections of the green economy to the informal economy.

An overwhelming majority of survey participants (15 of 17) and all interviewees (9 of 9) agreed that there are green activities taking place in the informal economy. These activities are described as mainly being driven by NGOs, and researchers or community organisations (Interviewee 3, 4 and 6). Although a number of projects have been initiated by different levels of government, Interviewees 3, 4 and 6 indicated that the level of commitment and dedication to such government-run projects is less than desirable. Regardless of outside intervention, Interviewee 5 suggested that some informal economy activities may even be 'greener' than their formal counterparts.

However, the notion that green activities occur in the informal economy is not uncontested. From the survey, 88% (15 of 17) of respondents agreed that there are green activities taking place in the informal economy, whereas 12% (2 of 17) disagreed. One such contestation revolved around the lack of regulation whereas another related to the motivation or intent of informal workers to be green. In contrast to this view, Interviewee 3 suggested that there is willingness and an understanding by some informal actors to participate in green activities. Interviewee 9, an informal settlement resident, demonstrated this willingness and understanding by describing the problems with 'earth and air pollution' and suggesting 'we need to do something about it ourselves'.

When asked to describe green activities taking place in the informal economy, online survey respondents identified the following: (1) subsistence farming; (2) bio-processing, management and trade; (3) recycling; (4) waste picking; (5) waste to compost activities; (6) use of renewable energy and other fuel saving innovations; and (7) rainwater harvesting.

Green economy activities in national policies and plans

A number of the green activities taking place in the informal economy were also recognised by national policies and plans related to the green economy as well as by green economy and informal economy practitioners who were interviewed.

Bioprospecting and biotrade

The Bioeconomy Strategy35 makes several references to bioprospecting as connected to indigenous knowledge systems, whilst the Ten Year Innovation Plan24(p.11) illustrates the connection as an 'interface between biodiversity heritage, indigenous knowledge systems and new development in genomics'. The advantages of bio-composites are described in the Industrial Policy Action Plan37(p.128) as including 'a reduced environmental footprint, reduced energy consumption in production, and health and safety benefits' as well as offering 'potential for new enterprise development and job creation, including in rural communities'.

Recycling and waste picking

Within the waste sector, recycling and waste picking activities are recognised as contributing to the green economy and as involving the informal economy. The National Waste Management Act, for example, aims to 'stimulate job creation and broaden participation by SMEs [small and medium enterprises] and marginalised communities in the waste sector'.30(p.27)

Waste collection and recycling was recognised by the majority of survey respondents (7 of 11) and all interviewees (9 of 9) as providing 'informal green jobs' making it the most recognisable of the activities. There is also much potential for further exploration, for example, through waste to compost activities and waste to fuel projects (Respondent 3). Interviewee 2 also suggested that within the value-chain for the recycling of waste in South Africa, certain levels of activity are already taking place within the informal economy with much scope for expansion.

Field observations indicated that some recycling activities are taking place within informal settlements. The recycling project at Site B is driven by a single member of the community. The recyclable material is collected from the individual households and then stored until it can be collected by a formal recycling business. The level of recycling however varies with community cooperation and is therefore both sporadic and small-scale in nature. From the issues pertaining to the level and quality of recycling in informal settlements, there may be a need for greater incentives and support for those individuals and communities that want to expand their efforts.

A further connection could also be made between recycling activities and the craft sector. The Industrial Policy Action Plan37 makes no explicit connection between the craft industry and the green economy, however, it does place emphasis on the benefits of localisation. The craft industry is described as being predominantly small-scale and informal, thus linking it to the informal economy. The potential here lies in connecting it with recycling activities, by using recycled materials to create marketable artefacts. For example projects such as Trashback and the Waste to Art Market (Respondent 6), which connect to the informal economy, localisation and the green economy.

Small-scale and subsistence farming

Along with several survey respondents (Respondent 1, 6, 7), Interviewees 1 and 2 described subsistence farming as green activities taking place in the informal economy. The connection between subsistence or small-scale farming and climate change is also made explicit by the National Climate Change Response Paper29(p.23), which proposes the following response:

Educate subsistence and small-scale farmers on the potential risks of climate change, and support them to develop adaptation strategies with on-farm demonstration and experimentation. Adaptation strategies will include conservation agriculture practices including water harvesting and crop rotation, and will prioritise indigenous knowledge and local adaptive responses.

In the context of climate change, the National Development Plan33(p.89) emphasises the need for innovative responses whilst also referring to the role of subsistence farmers:

The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, for example, is working to achieve food security for Africa by promoting sustainable agricultural growth through smallholder farmers. Recognising that smallholders - mostly women - produce most of Africa's food today with minimal resources and little government support...

As noted by the final point above, there is a disconnect between agricultural policies and the informal economy. Interviewee 1 describes the food system in South Africa as being 'managed and driven in a very entrepreneurial way, [and] the State is very absent from any of those structures'. The implication is that there are 'very few policies structurally that seek to enable the informal economy'.

Interviewee 2 suggested that a lack of support for small-scale farmers may have an impact on food security, and therefore have wider repercussions. In order to address the disconnect from the informal economy and to promote wider food security, Interviewee 1 proposed that the city formally adopts a food strategy that engages with the food system across all of its complexity; and that it adapts and adopts a citylevel mandate from the bottom up. This strategy may involve alternative processes where citizens come together to assert a different kind of agency in terms of city governance. A third component revolved around the criminalisation of certain activities, but which are not necessarily acted upon or enforced, because it is recognised that action could have negative effects on the wider and often impoverished communities they serve. As indicated by Interviewee 1, there are, however, numerous repercussions and complications associated with this final point that should also be acknowledged.

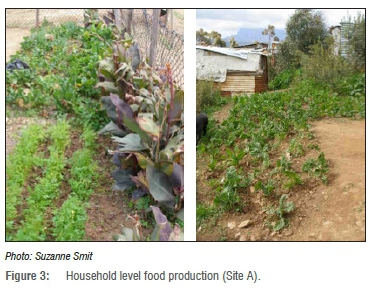

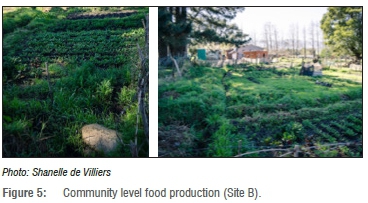

Small-scale and subsistence farming activities were observed in both the informal settlements (Site A and Site B) (Figures 3 to 5). The type, quantity and quality of produce varied according to plot size and aspect, season, soil quality, access to tools, and individual and financial constraints. In general, all food was grown for personal consumption by the individual households and the surplus then either sold or donated to the community members.

Green infrastructure, technology and construction

One way of connecting the green economy with the informal economy is through the introduction of green infrastructure and technologies. The use of renewable energy, rainwater harvesters, bio digesters, construction through eco-design, and bio-mimicry for solid and waste water treatment were recognised as projects taking place in a number of informal settlements (Interviewees 4, 6, 7 and 9). Small-scale solar installations were observed as being promoted and trialled in both informal settlements in order to help address the lack of access to energy.

Another energy related project observed at both sites incorporated the use of a bio-digester. Principally, the gas emissions from human waste are captured and transformed into gas for cooking, thereby creating a more sustainable form of energy. This project may provide several social, economic and environmental benefits, but community buy-in at Site B was problematic. Observations before and after installation indicated that there were certain benefits to upgrading the community toilets and although residents were initially excited by and involved in the upgrading process; one year later, only one toilet and bio-digester unit remains operative, partly because of community apathy and interpersonal conflict.

The difficulties associated with green projects in informal settlements reiterate the need for greater and better quality engagement with informal actors and entities. Nonetheless, if handled well, such projects may produce several social and economic gains in addition to environmental benefits. A number of interviewees indicated that green projects have the potential to create informal green jobs and also to assist municipalities with their infrastructure and resource constraints (Interviewees 4, 6 and 7). 'Decentralised infrastructure is about a completely different model of management and ownership' (Interviewee 7), and contains a variety of opportunities in relation to 'upcycling'; creating economic opportunities and assets that the poor can capitalise on; and can positively impact people's living conditions (Interviewees 4, 6 and 7).

It is felt that there is much scope for the informal economy in the green economy 'due to the number of sectors of work that could be included beyond just the construction industry' (Interviewee 2) and in terms of 'unlocking new value streams' (Interviewee 4). The job creating potential of green infrastructure may therefore be a topic for future study as well as a descriptive study of the number of informal worker groups in the green economy, their make-up, and the social, environmental and economic impact that these technologies have for those working and living in informal conditions.

Mechanisms to improve current planning and policy environment

The third research question aimed at recognising the ways in which the current planning and policy environment could improve. Therefore, it was deemed necessary to first explore both the challenges and the opportunities associated with connecting the green economy to the informal economy. Combining results from the online survey and the semi-structured interviews, the following SWOT analysis (Table 3) identifies the range of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats pertaining to connecting the green economy to the informal economy in South Africa.

The SWOT analysis considered a range of factors or conditions that may either help or hinder such connections (Table 3). The strengths and weaknesses relate to conditions within government or organisational control, whereas the opportunities and threats relate to factors outside or external to direct control.

From Table 3 it may be surmised that there are two types of conditions that negatively affect connections between the green economy and the informal economy. These connections may be considered as either related to organisational processes, structures and procedures, which fall within the purview of an organisation; or to individual and cultural differences, which fall outside the scope of organisational control. Table 3 also indicates that the benefits of connecting the green economy to the informal economy may be considered as intentional objectives, whereas the opportunities relate to indirect or unintended consequences.

Many of these benefits and opportunities are interconnected and cut across the three pillars of sustainable development, that is, the social, economic and environmental spheres. These benefits and opportunities align with international4 and national28 definitions of green economy and, it may be argued, echo the ideals of an inclusive green economy. Connecting the green economy to the informal economy in South Africa is recognised by participants as contributing to an inclusive green economy and therefore warrants the call for greater engagement between the informal economy and the green economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication.

Support for connecting green economy and informal economy

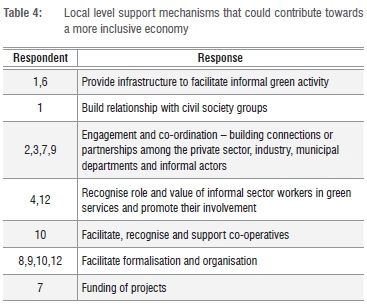

Beyond identifying positive and negative factors associated with connecting the green economy to the informal economy, survey respondents and interviewees were asked to identify how informal green activities taking place in the informal economy could be supported. The following section describes these support mechanisms at different levels of organisation.

Local government or city level

A number of challenges were recognised at municipal level that impede a supportive or enabling environment for engaging the informal economy. These challenges included procedural and bureaucratic processes; lack of vision or leadership; lack of long-term commitment; lack of transparency; various forms of internal and external politics; competition for resources; lack of capacity and/or capability; pressure to conform and comply; and individual and interpersonal issues (Interviewees 1 to 9).

For a number of participants, recognition of and engagement with the informal economy were key support mechanisms, particularly in terms of inclusivity. Other support mechanisms related to infrastructure provisioning, improved coordination, funding, and facilitating processes for formalisation and organisation (see Table 4).

The notion of organisation was a recurring theme underlying the process of engagement. For some, the 'lack of organisation' in the informal economy was a major challenge. Several interviewees (1, 2 and 5) however indicated that the informal economy in general is not 'unorganised', as there may be a number of organisational structures at any given time, for example, those based on gender, seniority, and tribal or political affiliation. At the same time, however, it was recognised that not all forms of organisation were conducive to wider or meaningful engagement. It would seem that both the level and type of organisation were important factors in determining the level and quality of engagement between green economy practitioners and the informal economy.

Organisational and procedural challenges aside, personal perceptions and attitudes may also play an important role in the quality and level of engagement between municipalities and informal actors. Interviewee 6 pointed out that 'it requires a specific mind-set or attitude to make something work in an informal settlement', a mind-set which several interviewees (2, 5, 6 and 7) felt was very much absent at local level. Support mechanisms at local level were also identified as relating to the capacity and capability of municipalities to deal with complexity; to reconcile formality with informality; and to develop new models of engagement (Interviewees 1, 4, 6 and 7).

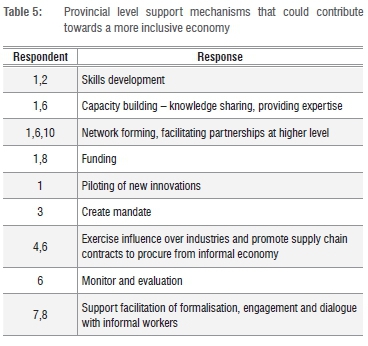

Provincial government

As previously described, some of the main barriers for connecting the green economy to the informal economy are related to lack of capacity, mandate and awareness at local level. Many respondents therefore indicated that provincial level support mechanisms need to address such challenges (Table 5).

It was also suggested that provincial governments have a responsibility to assist in bridging the gap between national policy and local practice and to recognise and support the informal economy, particularly in relation to facilitating partnerships and networks at a national level.

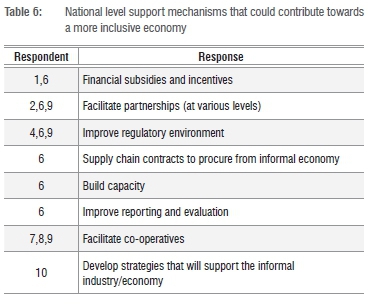

National government

Some of the barriers and challenges for connecting the green economy to the informal economy at national level related to lack of interdepartmental cooperation, lack of coordination and alignment of policies and in some cases, lack of capacity or willingness to engage with the informal economy (Interviewee 1, 2 and 5). Survey responses indicated the need for improving the regulatory environment, facilitation of partnerships at various levels (including at international level) and facilitation of cooperatives, as key support mechanisms (Table 6).

As previously indicated, there is a need for greater consistency in the interface between polices and/or practices by national government. According to Interviewee 2, in contrast to current 'top-down tendencies' support mechanisms may include a 'type of multi or inter ministerial structure' which is mandated to engage with the informal economy. A second supportive measure included recognising the different informal worker groups operating in the green economy (Interviewee 5). It is worth noting that the former support mechanism may assist in horizontal coordination and the latter with vertical coordination. For example, Interviewee 5 explained that identifying the different worker groups 'helps to navigate [the complexity]' and that 'by understanding it by worker group and then thinking it through per worker group' will improve sectoral or vertical coordination.

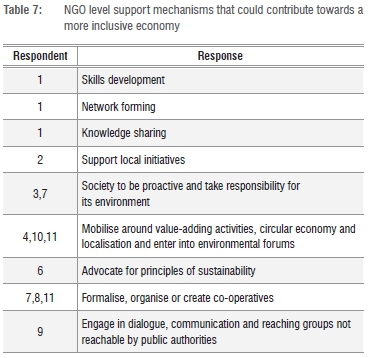

NGOs or civil society groups

Several interviewees (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) recognised the role of civil society groups or NGOs in connecting the informal economy to the green economy in South Africa. A number of support mechanisms pertaining to NGOs were recognised by survey respondents (Table 7).

Key support mechanisms reported by survey respondents related to the facilitation of organisations within the informal economy and the mobilisation of NGOs around green activities. In previous discussions on connecting the green economy with the informal economy, the focus fell on green economy practitioners and their role in engaging informal actors. As indicated above, and as reiterated by Interviewee 5, there is also a need for NGOs that represent and advocate for the informal economy to engage with the actors and entities promoting the green economy.

Such engagements would require practitioners to reconsider the green economy space in terms of the opportunities it may hold for informal economy actors (Interviewee 5). NGOs can further contribute to a more enabling policy and planning environment by assisting in 'mapping the size of the opportunity to enable further interventions' (Respondent 6); identifying different informal worker groups that operate in the green economy; and by participating at different levels, local to international, in discussions on the green economy (Interviewee 5).

Although NGOs may offer much assistance in connecting the green economy to the informal economy, they may also unwittingly impede such processes through poor representation; ideological differences; conflicting agendas and the tendency to 'roll-out a blueprint formula that works in some places' but that does not take context into account (Interviewees 1, 3, 4 and 5). These challenges therefore also warrant further attention if a more enabling policy and planning environment is to ensue.

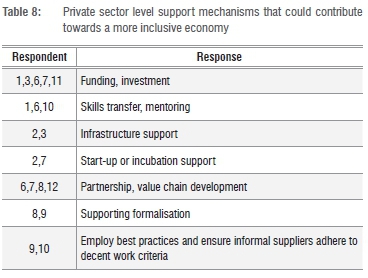

Private sector organisations

Finally, survey respondents were asked to consider the role of private sector organisations in contributing to a more inclusive green economy and several support mechanisms were identified (Table 8).

The most pertinent mechanisms related to formalising relationships through partnerships and investment in small and micro enterprises in terms of both financial support and skills transfer, as well as the development of broader value-chains that incorporate informal actors or entities. The notion of an expanded value-chain was also supported by a number of interviewees. For example, Interviewee 4 pointed to opportunities in the green infrastructure and technology sector, whereas Interviewee 2 referred to opportunities within the waste sector.

Overall, support mechanisms for connecting the green economy to the informal economy would require a paradigm shift in terms of what an inclusive green economy is; who the stakeholders and role-players are; as well as in addressing how and to what extent they are engaged.

Conclusions

We explored the connections between the green economy and the informal economy in the South African context using multiple methods. Results from observations, an online survey and interviews indicated that the informal economy is mostly invisible, in part because of a lack of conceptual consensus and interpretation but also as a result of insufficient recognition or awareness of the informal economy's role within the green economy space or how to engage with it successfully.

The paper revealed a number of possible connections between the green economy and the informal economy in the form of green activities, indicating that the informal economy may add much value to an inclusive green economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication. The results also indicated a number of opportunities and benefits related to connecting the green economy to the informal economy, which warrant further investigation.

In terms of improving, enabling or supporting connections between the green economy and the informal economy, the survey and interview of several green economy and informal economy practitioners and policy influencers revealed a number of support mechanisms. These mechanisms were identified as addressing several barriers and challenges at various levels of organisation, and if incorporated, may assist in bringing about more empowering and inclusive practices or enabling policy and planning environments.

Although every effort was made to enhance the validity and reliability of the study through triangulation, the size and quality of the sample may be improved in terms of greater representation of informal economy actors or entities. Greater representation would involve cutting across a greater geographical region with varying conditions as related to climate, local bylaws, and social and economic practices and procedures, to allow for broader assertions and comparisons between provinces. It is further recommended that future studies include a focus on (1) profiling informal worker groups within the green economy; (2) exploring 'organisation' in the informal economy; (3) the role of NGOs and collectives in the green economy; (4) government process and change management for an inclusive green economy; and (5) a value chain analysis of green economy opportunities at the bottom of the pyramid.

Although the list of possible future research may be infinite, the implications of the study are relatively clear: for South Africa to achieve an inclusive green economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication, it needs to engage with the actors and entities operating in the informal economy. To do so, both informal economy and green economy practitioners and policy advisors would need to apply a new 'lens' for considering the informal economy and its contribution to the green economy. This new lens involves a paradigm shift in terms of how the informal economy is perceived and approached, as well as pertaining to what an inclusive green economy entails and proposes.

Furthermore, a more open and enabling policy environment may greatly assist in not only recognising current opportunities, but also in leading to an alternative economic model. That is to say, an economic model in contrast to the dominant neo-liberal approach and which embraces the plurality of South African society; is open to alternative forms of development; promotes inclusivity and diversity; and which may be more conducive to socially equitable and environmentally sustainable development.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by funds received from the National Research Foundation's Community Engagement Programme awarded to Stellen bosch University.

Authors' contributions

S.S. conducted the study and wrote the manuscript; J.K.M. made conceptual contributions and assisted with editing.

References

1. United Nations Environment Programme and Department of Environmental Affairs. Green economy modelling report for South Africa (SAGEM): Focus on the sectors of natural resource management, agriculture, transport and energy [document on the Internet]. c2013 [cited 2013 Sept 09]. Available from: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/greeneconomy_modelingreport.pdf. [ Links ]

2. Musango JK, Brent AC, Bassi AM. Modelling the transition towards green economy in South Africa. Technol Forecast Soc. 2014;87:257-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.12.022 [ Links ]

3. Oelofse C, Scott D, Oelofse G, Houghton J. Shifts within ecological modernization in South Africa: Deliberation, innovation and institutional opportunities. Loc Environ: Int J Justice Sustain. 2006;11:61-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13549830500396214 [ Links ]

4. United Nations Environment Programme. Towards a green economy: Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication [document on the Internet]. c2011 [cited 2014 Jan 07]. Available from: http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/GreenEconomyReport/tabid/29846/language/en-US/Default.aspx [ Links ]

5. Resnick D, Tarp F, Thurlow J. The political economy of green growth: Cases from Southern Africa. Public Admin Develop. 2012;32:215-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pad.1619 [ Links ]

6. Death C. The green economy in South Africa: Global discourses and local politics. Politikon. 2014;41:1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2014.885668 [ Links ]

7. Swilling M, Musango JK, Wakeford J. Introduction: Deepening the green economy discourse in South Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press; Forthcoming 2015. [ Links ]

8. Allen C. A guidebook to the green economy. Issue 2: Exploring green economy principles. Division for Sustainable Development, UNDESA, [document on the Internet]. c2012 [cited 2014 Jan 07]. Available from: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=743&menu=35. [ Links ]

9. United Nations. The future we want. Outcome document for the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20); 2012 June 13-22; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [document on the Internet]. c2012 [cited 2014 Jan 05]. Available from: https://rio20.un.org/sites/rio20.un.org/files/a-conf.216l-1_english.pdf.pdf. [ Links ]

10. Devey R, Skinner C, Valodia I. Informal economy employment data in South Africa: A critical analysis. Cape Town: Development Policy Research Unit; 2003. [ Links ]

11. Statistics South Africa. Quarterly labour force survey: Quarter 4. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2013 [ Links ]

12. Economic Development Department. Economic policy development: Second economy. [Document on the Internet]. c2015 [cited 2015 April 20]. Available from: http://www.economic.gov.za/about-us/programmes/economic-policy-development/second-economy [ Links ]

13. Rogerson CM. 'Second economy' versus informal economy: A South African Affair. Geoforum. 2007;38:1053-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.005 [ Links ]

14. International Labour Organisation (ILO). Report of the Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians, 2003 Nov 24-Dec 03; Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

15. Smit S., Musango, JK. Towards connecting green economy with informal economy in South Africa: A review and way forward. Ecological Economics. 2015;116:15-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.022]. [ Links ]

16. Dawa FO, Kinyanjui MN. Green economy and sustainable development: Which way for the informal economy? Think piece produced as part of a series for the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) document on the Internet]. c2012 [cited 2013 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.unrisd.org/unrisd/website/newsview.nsf/%28httpNews%29/43B2464B82F227A1C1257A41002D14B2?OpenDocument [ Links ]

17. Davies R, Thurlow J. Formal-informal economy linkages and unemployment in South Africa. S Afr J Econ. 2010;78(4):437-458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2010.01250.x [ Links ]

18. Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. Second economy strategy: Addressing inequality and economic marginalisation [document on the Internet]. c2009 [cited 2014 Feb 06]. Available from: http://www.tips.org.za/files/Second_Economy_Strategy_Framework_Jan_09_0.pdf. [ Links ]

19. Borel-Saladin JM, Turrok IN. The impact of the green economy on jobs in South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2013;109(9/10), Art. #a0033, 4 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/a0033 [ Links ]

20. Smit S. Towards an 'inclusive green economy' for South Africa: Engaging with the informal economy. Stellenbosch: Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences, Stellenbosch University; 2015. [ Links ]

21. Babbie E. The practice of social research. 8th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1998. [ Links ]

22. Montmasson-Clair G. Green economy policy framework and employment opportunity: A South African case study. TIPS Working Paper Series. Pretoria: TIPS; 2012. [ Links ]

23. Sustainlabour. Congress of South African Trade Unions and Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. Green jobs and related policy frameworks: An overview of South Africa [document on the Internet]. c2013. [cited 2014 Feb 08]. Available from: http://www.sustainlabour.org/documentos/Green%20and%20decent%20jobs-%20An%200verview%20from%20Europe%20FINAL.pdf [ Links ]

24. Department of Science and Technology. The ten-year plan for science and technology [document on the Internet]. c2008 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/documents/index.php?term=&dfrom=&dto=&yr=0&subjs%5B0%5D=70&p=3. [ Links ]

25. Republic of South Africa. Framework for South Africa's response to the international economic crisis [document on the Internet]. c2009 [cited 2014 January 27]. Available from: http://www.polity.org.za/article/framework-for-south-africas-response-to-the-international-economic-crisis-february-2009-2009-02-23. [ Links ]

26. National Planning Commission. Together doing more and better. Medium term strategic framework. A framework to guide government's programme in the electoral mandate period (2009-2014). Pretoria: The Presidency of the Republic of South Africa; 2009. [ Links ]

27. Department of Energy. Integrated resource plan: 2010-2013. [document on the Internet]. c2011 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.doe-irp.co.za/content/IRP2010_promulgated.pdf. [ Links ]

28. Department of Higher Education and Training. National skills development strategy III: 2011-2016 [document on the Internet]. c2012. [cited 2014 March 10]. Available from: http://www.dhet.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=A0v8W%2Bm3xHI%3D&tabid = 1131. [ Links ]

29. Republic of South Africa. National climate change response white paper [document on the Internet]. c2011 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/documents/detail.php?cid=315009. [ Links ]

30. Department of Environmental Affairs. National waste management strategy [document on the Internet]. c2011 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/documents/index.php?term=&dfrom=&dto=&yr=0&subjs%5B0%5D=49&p=6. [ Links ]

31. Economic Development Department. The new growth path: Accord 4 - Green economy accord [document on the Internet]. 2011 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/documents/index.php?term=&dfrom=&dto=&yr=0&subjs%5B%5D=92. [ Links ]

32. Department of Environmental Affairs. National strategy for sustainable development and action plan (NSSD1) 2011-2014. Pretoria: Department of Environmental Affairs; 2011. [ Links ]

33. National Planning Commission. National development plan, Vision 2030: Our future - make it work [document on the Internet]. c2012 [cited 2014 April 22]. Available from: http://www.npconline.co.za/pebble.asp?relid=25. [ Links ]

34. Department of Energy. Draft 2012 integrated energy planning report [document on the Internet]. c2013 [cited 2014 March 10]. Available from: http://www.energy.gov.za/files/IEP/IEP_Publications/Draft-2012-Integrated-Energy-Plan.pdf. [ Links ]

35. Department of Science and Technology. The Bio-economy strategy [document on the Internet]. c2013 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.dst.gov.za/images/ska/Bioeconomy%20Strategy.pdf. [ Links ]

36. Department of Water Affairs. National water resource strategy: Water for an equitable and sustainable future. 2nd ed [document on the Internet]. c2013 [cited 2014 March 10]. Available from: http://www.dwaf.gov.za/nwrs/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=3AVrHanrkfw%3d&tabid=91&mid=496 [ Links ]

37. Department of Trade and Industry. Industrial policy action plan 2014/15-2016/17 [document on the Internet]. c2014 [cited 2014 June 22]. Available from: http://www.gov.za/documents/index.php?term=&dfrom=&dto=&yr=0&subjs%5B%5D=112 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Suzanne Smit

School of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University

Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602

South Africa

Email: suzann3sm1t@gmail.com

Received: 04 Dec. 2014

Revised: 04 Feb. 2015

Accepted: 07 May 2015