Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Science

On-line version ISSN 1996-7489

Print version ISSN 0038-2353

S. Afr. j. sci. vol.111 n.7-8 Pretoria Jul./Aug. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/SAJS.2015/A0116

BOOK REVIEW

Brian W. van Wilgen

Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

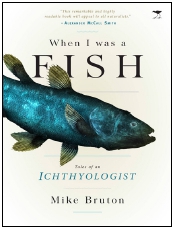

BOOK TITLE: When I was a fish: Tales of an ichthyologist

AUTHOR: Mike Bruton

ISBN: 9781431420575 (softcover)

PUBLISHER: Jacana Media, Johannesburg, ZAR246

PUBLISHED: 2015

With nearly 10% of all known species of birds, fish and plants, and 6% of mammal and reptile species, South Africa is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. Any biologist, ecologist or conservationist who sets out to work in this country in one of these fields is fortunate indeed, as this diversity offers a multitude of opportunities for a rewarding, eventful, influential and memorable career. Mike Bruton is one such person. He started a career as a freshwater ichthyologist studying the fishes in the lakes of northern KwaZulu-Natal, and moved on to being an academic, research director and science educator, among others. His career has been based in southern Africa, but has provided many opportunities for travel to exotic destinations. Rather than write an autobiography, Bruton has penned a 'memoir', which in his own words is 'simply a story [or rather, a collection of stories] of how a boy grew up to become a man who had a passion for fishes'.

As a student of zoology (and later an academic) specialising in ichthyology at Rhodes University, Bruton had a close relationship with (and for a while served as director of) the J.L.B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology. The institute was founded by the legendary James Leonard Brierley Smith, author of the well-known book The Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (1949), but arguably better known as the person who described the first known modern coelacanth. The discovery of this ancient fish, previously known only from fossils that dated back 80 to 350 million years, was one of the most remarkable scientific events of the 20th century. Smith's description of the first specimen was published in 1939 in the journal Nature, and his discovery (after a long search) of a second specimen in 1952, caught the world's attention in a big way. This story is recounted in Smith's book Old Fourlegs, in my view one of the most exciting works of non-fiction ever written. Bruton is of the opinion that, had these events not occurred, J.L.B. Smith would in all likelihood have remained an amateur ichthyologist, and the centre of southern African ichthyology would probably have developed in Cape Town or Durban, and not at Rhodes University in Grahamstown.

As a result of this association, a good deal of Bruton's book is focused on subsequent work on the ecology and conservation of coelocanths, regarded as an icon for marine conservation in the same way that the giant panda symbolises terrestrial conservation. Bruton is one of the few people lucky enough to have observed living coelocanths, an experience he describes in the book, and his passion for the topic is quite apparent. He describes in some detail the documentation of all known specimens, the study of their distribution, ecology and breeding strategies, and the ethical question of whether or not coelocanths should be caught for public display in aquaria.

Bruton's book, however, is not just about coelocanths. It contains a myriad of snippets from a long and eventful career, many personal, quite a few informative, and almost all very entertaining. These stories range from those about sharing his working environment with crocodiles and hippos at Lake Sibiya, to meeting a range of dignitaries including Queen Elizabeth II. Two chapters are devoted to the study and documentation of life-history strategies in fishes. Biologists and non-biologists alike should benefit from the insights into the life and times of fishes that are described in this book, as well as the way in which they are managed (or mismanaged). In some places, I would have liked to have seen more detail, but there is only so much one can fit into a memoir like this. For example, it is mentioned that the stocking of the newly formed Lake Kariba with alien fish to create a new fishery was 'epic and highly controversial', and that 'to our inexperienced and biased eyes the Kariba experiment appeared to be a huge success', but very little further detail is given.

Bruton also pays tribute to the many colleagues with whom he has worked over the years. It is the lot of science administrators that many of their research colleagues will end up better known than their managers. South Africa is a 'fish-crazy nation', and those who publish the detailed guides to fishes are more likely to become known to anglers, naturalists, ecotourists, aquarists and food gourmets than those who nurture the environment that makes these publications possible. Besides J.L.B. and Margaret M. Smith (J.L.B.'s wife, lifelong scientific collaborator and successor), specific mention is made of (for example) Paul Skelton, Phil Heemstra and Ofer Gon, who between them have produced the next generation of definitive books documenting regional fish faunas.1-3

Bruton provides an interesting perspective on conservation in his final chapter. This perspective was again obviously influenced by his long study of coelocanths, a species that has survived in a more-or-less unchanged form for hundreds of millions of years. During this time, many other life forms have come and gone, and new forms of life have evolved. Bruton argues that extinction is neither good nor bad, and that species extinctions simply make space for new species to evolve. Humanity's current concern over the conservation of endangered species may therefore be misplaced. We are simply modifying the planet in a way that will make the evolution of new life forms possible, but it will also render the world uninhabitable for ourselves. Given that life will continue with newly evolved forms long after humans are gone, our concern should rather be that humans are an endangered species. With that in mind, Bruton has devoted the closing phases of his career to science education.

This book is a mixture of adventure stories, entertaining anecdotes, scientific facts and interesting interpretations. The book should be of wide interest to many people from a range of backgrounds, and I would recommend it to anyone with an interest in biology, conservation, education or a career in the sciences.

References

1. Smith MM, Heemstra PC. Smith's sea fishes. Johannesburg: Macmillan; 1986. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-82858-4 [ Links ]

2. Skelton PH. A complete guide to the freshwater fishes of southern Africa. Johannesburg: Southern Book Publishers; 1993. [ Links ]

3. Gon O, Heemstra PC. Fishes of the Southern Ocean. Grahamstown: J.L.B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology; 1990. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Brian W. van Wilgen

Centre for Invasion Biology

Department of Botany and

Zoology, Stellenbosch University

Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602

South Africa

Email: bvanwilgen@sun.ac.za