Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.60 n.1 Stellenbosch 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/60-1-1259

ARTICLES

Social work practitioners' and supervisors' conceptualisation of supervision at the Department of Social Development, King Cetshwayo District: a polity dualism

Sandile Ntethelelo GumbiI; Ntombifikile Margaret MazibukoII; Mbongeni Shadrack SitholeIII

IUniversity ofKwaZulu-Natal, Department of Social Work, Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0819-3869 gumbisn4@gmail.com

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Department of Social Work, Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2072-8424 MazibukoN3@ukzn.ac.za

IIIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Department of Social Work, Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4075-0677 sitholem3@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The historical development of social service supervision reveals that the professional and organisational demands do not co-exist without challenges. The tension that often manifests between professional and managerial supervision is explained using the analogy of "polity dualism", a concept widely used in political science to describe the co-existence of democratic and traditional rulership. The study adopted a qualitative exploratory-descriptive design underpinned by an interpretive paradigm. Seventeen social workers and supervisors were purposively sampled at the Department of Social Development, King Cetshwayo District, KwaZulu-Natal. The findings were presented in terms of two main themes and two related subthemes. These included participants' understanding of supervision and relating their understanding of supervision with experience. The recommendations could be summarised to involve the need to limit supervisors' responsibilities to providing supervision only and to address the challenges posed by polity dualism by relying on professional supervision that offers more support and guidance and encourages collaboration between supervisors and supervisees.

Keywords: managerial supervision; neoliberalism; polity dualism; professional supervision; social worker; social work supervisor

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this article is twofold: (1) to gain an in-depth understanding of how social workers and supervisors conceptualise supervision in the social services sector, (2) and to explore how polity dualism influences the social service organisation as a context in which supervision is implemented. In attempting to explain the nature of supervision in the social services sector, the authors used the analogy of "polity dualism". Before explaining the three functions of supervision, it is worth indicating the relevance of polity dualism to this article. Holzinger, Kern and Kromrey (2016) describe polity dualism as a situation of the co-existence in which both democratic and traditional rulership apply simultaneously to the same population. While this concept is widely used in political science to describe the co-existence of the state and traditional systems, the authors became interested in the significance of traditional ruler-state dualism in social service organisations as a context in which supervision occurs. As in the duality of state and traditional systems at the political and administrative level, the influence of this dualism in social service organisations and supervision, in particular, cannot be disregarded and was therefore considered worth exploring in more detail.

The way that social workers and supervisors undertake supervision is directly linked to their conceptual understanding of supervision practice and social service organisations as a context in which supervision is practised. Tropman (2022) asserts that beyond the benefit of providing quality social services to clients by social workers, being well-supervised is also helpful to the supervisees in order for them to become better supervisors when the time arises. The supervisory relationship between social workers and supervisors is significant and often manifests through the quality of the services provided to clients (Caras & Sandu, 2014). While the supervision relationship is significant, supervision may also be viewed as having limitations if it does not address "the professional and organisational aspects of practice" (Rankine, 2019:67)

De Groot (2016) argues that effective supervision offers a platform for ensuring an integrated balance between administrative, educational and supportive functions and subsequently provides the most appropriate environment in which social workers can develop their capacities. An inability of supervisors to maintain a balance in implementing the three functions of supervision results in supervision practice-related inefficiencies. Wong and Lee (2015) assert that social work supervisors are often confronted with challenges when it comes to the simultaneous execution of administrative, supportive and educational functions of supervision, as they are often expected to perform dual roles as managers and clinical supervisors. The implications of this shortcoming are likely to be felt by the key role players, namely social workers, the organisation they work for and the client system. To maintain a balance, supervisors need to adequately implement the administrative, supportive and educational functions. A growing body of literature suggests that social work supervision is mainly conceptualised in terms of the administrative function, which emphasises accountability and managerialism. The prioritisation of the administrative function of supervision by social work supervisors stems from the focus on managerial rather than professional supervision and compromises the quality of supervision provided to the supervisees (Engelbrecht, 2013; Sithole & Shokane, 2023; Vetfuti, Goliath & Perumal, 2019).

In this regard, social work supervisors are likely to end up neglecting the need to integrate these functions because they do not always complement each other and resort to focusing on just one function (Hawkins & Shohet, 2012). The supervisor should apply these functions purposefully and according to the needs of the supervisees to enhance their practice. Supervision has taken a managerial and performance management character, which is not always desirable and may result in a situation where supervisees experience supervision as a harmful rather than helpful practice (Chibaya & Engelbrecht, 2022; O' Donoghue & Engelbrecht, 2021). For social work supervision to become helpful rather than harmful, it has to take on the characteristics of professional supervision. Caras and Sandu (2014) assert that professional supervision contributes to the growth and development of good social workers. The professional growth and development of social workers ultimately enables the organisation as a social service agency to render quality and effective services to its clients.

In the social service context, the historical development of social services and supervision reflects the plural nature of the democratic era in which social service organisations operate. In terms of the polity dualism analogy in the context of social service organisations, the professional and organisational demands could be viewed not as just co-existing, but also as characterised by an underlying tension. White (2015:252) asserts that "the organisational cultures of many social work agencies have been refashioned under the impact of modernisation and managerialism". In contrast to managerial supervision, professional supervision enables practitioners to engage in a relationship with a supervisor "enabling both a place and space to refine and develop professional identity, knowledge and skills and for reflectively examining the challenges faced in everyday practice" (Karvinen-Niinikoski, Beddoe, Ruch & Tsui, 2019:87).

The literature shows that the notable preference for managerial over professional supervision can be mainly attributed to the dominance and influence of neoliberal discourse in social service organisations. In a study conducted in the DSD in 2020, it emerged that, practically speaking, there was "notable centralisation and emphasis on the managerial supervision, with professional supervision pushed to the periphery" (Sithole, 2020:77). One explanation for this was that:

Neoliberalism and managerialism have increased surveillance and control and replaced collegiality and trust with contracts, competitiveness, individuality and performance indicators, supporting a compliant and technically skilled workforce rather than critically reflexive professionals. (Dlamini & Sewpaul, 2015:477)

Rankine (2019) explains that social workers currently operate in a managerial and neoliberal environment that threatens their ability to engage in a critical reflective supervision practice and consequently forces them to engage in supervision agendas that are concerned with measuring outputs and efficiency. While the construct of neoliberalism lacks a uniform definition, several authors have written on "an increasing pressure on social service organisations to conform to the political, economic and ideological precepts of neoliberalism" (Patel, 2019:3). Among the operational consequences of the influence of neoliberalism, according to Spolander (2019), is the prioritising of efficiency, effectiveness and economics above other predominant social work values such as social justice.

CONTEXTUALISING SUPERVISION

The literature depicts supervision in social service agencies to be a context-driven process (Beddoe, 2015). To contextualise social work supervision, Khosa (2022) explains that it is crucial to take into account the context within which supervision takes place. For the purposes of this article, supervision practice is contextualised within the King Cetshwayo Department of Social Development (DSD) as a social service organisation characterised by high levels of polity dualism.

The Department of Social Development as a social service context

Supervision plays a significant role in the DSD in helping social workers perform their functions efficiently to fulfil the Department's mandate and vision. The mandate of the DSD is to "provide social protection services and lead government efforts to forge partnerships through which vulnerable individuals, groups and communities become capable and self-reliant participants" in their development, (DSD, 2021:21). This mandate is derived from section 27(1)(c) and section 28(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (RSA, 1996), which provide rights for the provision of social assistance to vulnerable populations and protects the rights of children, respectively. The White Paper for Social Welfare (RSA, 1997) (herein referred to as the White Paper) was developed to fulfil the mandate provided by the Constitution of RSA (1996) and adopted a developmental approach to social welfare and the framework for the provision of social welfare services. The White Paper (RSA, 1997) recognises social workers as the main practitioners who must lead in the implementation of the policies.

Therefore, social work supervision becomes critical for social workers because it becomes the primary resource for increasing levels of autonomy of social workers in the provision of efficient and effective services to their clients (Caspi & Reid, 2002). The Supervision Framework for the social work profession in South Africa developed by the Department of Social Development (DSD) and the South African Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSP) states that supervision can take place in many different contexts and employments; the core significance of social work supervision is that it is a professional activity ingrained within social work as a demanding and dynamic profession (DSD & SACSSP, 2012).

Social work as a profession exposes social workers to different contexts where they face different challenges in working with diverse clients, and hence, social work professional supervision becomes fundamental in social work professional practice, (Nickson, Gair & Miles, 2016). Social workers are regarded as key frontline cadres in the delivery of quality social welfare services, and this requires them to be afforded quality and efficient supervision (DSD & SACSSP, 2012). Ncube (2016) mentions that since social work supervision plays a critical role in guiding social workers to provide quality social welfare services, the application of supervision should, therefore, be specific to the specific context within which it is practised, in as much as supervision can be applied across different contexts.

The King Cetshwayo District DSD as a rural-based social service organisation

The King Cetshwayo District of the DSD is located north-east of KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. The district is comprised of five municipalities, namely the City of uMhlathuze, uMfolozi, Nkandla, Mthonjaneni and uMlalazi. It is also the home of five DSD service offices that serve the people residing in the respective districts. Among the reasons for choosing the King Cetshwayo District DSD as the locality for this study was that this district reportedly services communities that are situated in a setting that is mainly rural and only a small part being urban (Gumbi, 2021). It was also relevant as one of the districts that provide social services aimed at empowering marginalised and vulnerable people. Phungwayo (2012) states that the DSD is the custodian of social services that purport to empower vulnerable groups in South Africa. However, this district is characterised by high levels of polity dualism.

Polity dualism

Polity dualism in the context of the King Cetshwayo District DSD relates to the co-existence of the traditional and state sectors; both democratic and traditional rulership apply simultaneously to the same population (Holzinger et al., 2016). Holzinger et al. (2016) describe contemporary traditional forms of governance as co-existing with the political institutions and laws of the state. The King Cetshwayo District is located at the north-east of KwaZulu-Natal with most of its land administered by the Ingonyama Trust Land under the Traditional Authority of the Zulu Kingdom. Traditional ruler-state dualism is common in regions riddled with internal conflict, delayed democratisation and stalled development (Holzinger et al., 2016). All these factors are relevant in this study locality as they influence the context in which social services are provided. Ubink and Duda (2021) add that traditional rulership creates unequal power relationships that affect access to goods, services and natural resources.

In the identified district, people are subject to the traditional authorities while also being under municipal administration. In the context of social work practice, social work practitioners may find themselves having to practise within a more cultural and traditional environment and, at the same time, having to provide services in a municipal administrative environment. The tensions that prevail between professional and organisational mandates in social service organisations could be viewed as being influenced by the co-existence of two systems.

In a South African context, where social work supervision has been described as tending largely towards managerialism, the supervision formation is clearly influenced by external factors (Chibaya & Engelbrecht, 2022; Sithole, 2020). The challenge stems from the uniquely peculiar sets of clients' needs emanating from their traditional and cultural orientations while at the same time relying on a democratically founded institution for intervention with different operative mechanisms, a situation that could frustrate the practice of effective supervision.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Patel and Patel (2019) define research methodology as principles for conducting research scientifically. The key elements in this regard are the generated participants' accounts and findings achieved through a logical, systematic, and step-by-step research process undertaken.

Research approach, design and paradigm

Qualitative research is employed to elicit in-depth truths and understanding through observation, engagement and listening (Crabtree & Miller, 2022). This study adopted the qualitative research approach with an exploratory-descriptive design. This research design was deemed appropriate for the study as it allowed for an open, inductive and flexible approach to exploring and describing how participants conceptualise social work supervision in the King Cetshwayo District DSD, which is marked by polity dualism. The interpretivist paradigm seeks to clarify the meaning of the participants' experiences. Krysik (2018) describes an interpretivist paradigm as concerned with understanding social conditions through construing the meanings that individuals ascribe to their experiences.

Sampling

Purposive sampling was used to select the participants of the study, comprised of social workers and supervisors. Daniel (2012) describes purposive sampling as a procedure in which participants are selected from the target population based on their fitness for the study and in terms of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. The researcher purposively sampled participants from King Cetshwayo District at oNgoye, Richards Bay, and Lower Mfolozi service offices. Following data saturation, a total of seventeen participants, consisting of thirteen social workers and four supervisors, were included in the study. Both social workers and supervisors were part of the sample of this study because the Supervision Framework for the social work profession in South Africa (SACSSP & DSD, 2012) tasks supervisors with mainly being responsible for the implementation of supervision to social workers and mandates social workers to be recipients of supervision. The main inclusion criteria for the sample were that the participant should be (1) employed by the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Department of Social Development on a full-time basis; (2) placed in any of the DSD services situated at King Cetshwayo District Municipality; (3) either a social worker or social work supervisor; (4) subject to supervision or entrusted with the supervisory responsibility, respectively; and (5) registered as a social worker with the South African Council for Social Service Professions.

Data collection

In-depth semi-structured interviews were utilised to collect data from the participants. Mahat-Shamir, Neimeyer and Pitcho-Prelorentzos (2021) assert that in-depth interviews are employed in a study to gauge the perspectives of participants in order to uncover information that can be meaningful to address the research questions. Both telephonic and face-to-face interviews were used in accordance with the prepared interviewing guide, which contained questions that were open-ended. The duration of each interview was between 30 and 60 minutes, which allowed the researcher sufficient time to elicit relevant data from the participants.

Data analysis

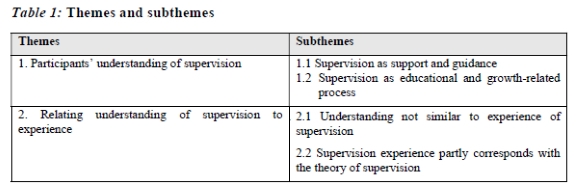

For data analysis, the researcher adopted thematic analysis to analyse and interpret the collected data. Mahat-Shamir, Neimeyer and Pitcho-Prelorentzos (2021) assert that the thematic analysis technique includes identifying the codes, categories and themes that emerge through the systematic analysis of data. Through the thematic analysis, data were identified, analysed and coded into themes. To analyse data, the researcher closely followed the six steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006): data familiarisation, forming codes, inducing themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing a report. Two main themes and two related subthemes emerged from this study. These are dealt with in the findings section below.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The researcher observed research ethical principles while collecting data. Amongst the ethical principles were permission to conduct the study, voluntary participation, informed consent and confidentiality.

Ethical and gatekeeper permission

Obtaining ethics approval from an independent Research Ethics Committee (REC) is an acceptable practice in research studies that involve human beings as participants directly or indirectly, taking into account the implications of the research on the participants (Gelling, 2016). To gain access to participants, the researcher needs gatekeeper approval. Gatekeepers can be individuals or institutions who control access to a specific area, institution or organisation that is a key to the research study (Singh & Wassenaar, 2016). The ethical approval for this study was granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) through the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSSREC). The ethical clearance reference number allocated was HSSREC/00002004/2020. The gatekeeper letter was sourced from the KZN provincial DSD, and approval was granted by the KZN provincial Head of Department (HOD). Access to DSD service offices at King Cetshwayo District was granted by the district director and the respective service office managers, respectively. After that, arrangements for the actual data collection had to be made with the supervisors and social workers.

Voluntary participation and informed consent

The principles of voluntary participation and informed consent ensure that participants make informed decisions without being coerced. Clark-Kazak (2017) asserts that the participants should be afforded the right to withdraw from the study after you provide them with information about the study and specify what is required of them. Informed consent enhances the participants' right to autonomous decision-making as it grants them an opportunity to decide whether their participation in the research study will be compatible with their interests, values and beliefs (Pietilä, Nurmi, Halkoaho & Kyngäs, 2020). Participants were provided with information that pertained to the study, and their rights to participate or withdraw were guaranteed. Consent forms were provided to participants and signed voluntarily.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is one of the fundamental and basic ethical principles of social work research. It upholds the participants' right to privacy regarding what they share in the course of the data-collection process and allows them to feel more at ease with participation and sharing their experiences (Kamanzi & Romania, 2019). Confidentiality was guaranteed, which allowed participants to express their feelings and experiences freely. In this regard, the participants' real identities were protected through the use of codes. Social workers were coded as SWP 1 to SWP 13, while social work supervisors were coded as SWS 1 to SWS 4. The code SWP represents social work practitioner, whereas code SWS refers to social work supervisor.

Trustworthiness

As far as trustworthiness is concerned, credibility, confirmability, dependability and transferability were given due attention. Credibility is described as entailing confidence in the accuracy and truthfulness of the findings (Amankwaa, 2016). In this study, credibility was ensured through the adoption of a suitable research approach, paradigm and design that enabled the researcher to apply an appropriate data-collection instrument. Dependability has to do with the stability of findings over time (Connelly, 2016). Dependability was ensured through constantly reflecting on the methods employed in the study and the entire research process. Transferability refers to the applicability of the findings to other contexts (Amankwaa, 2016). The findings cannot be generalised but can be replicated in related contexts. Transferability can be thought of in terms of context-bound extrapolations, which the researcher could enable by providing a deep and rich contextual description of context and participants (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2019). Other DSD service offices are viewed as having a set of similar characteristics to those of the King Cetshwayo Districts across the KZN province. Connelly (2016) describes confirmability as focusing on the degree of consistency of the findings. This aspect was ensured through conducting member checks with the participants.

FINDINGS

This section represents the findings of the study based on the collected data as guided by the research questions. Findings are presented in themes and subthemes as shown in the Table 1 below.

Theme 1: Participants' understanding of supervision

Participants were interviewed on how they conceptualised and understood supervision, which is essential in their practice as social workers. Participants were asked to define supervision and describe how they understand it. In defining supervision, participants related supervision to its functions, namely administrative, supportive and educational. Engelbrecht (2010) mentions that supervision has been defined in various ways, with social workers and social work supervisors conceptualising supervision in terms of control, guidance and support. Emerging from the participants' responses, support and guidance emerged as the essential elements in the participants' conceptualisation of supervision.

Subtheme 1.1: Supervision as support and guidance

"Support" and "guidance" were predominant in participants' responses as they provided their perspectives on how they conceptualised social work supervision. The role of supervision practice in providing support and guidance was described as necessary to contribute to social workers' skill development and professional maturity. Participants' responses were as follows:

Supervision is the guidance and support from somebody who is your senior in the workplace where he/she provides you with information that ensures that you have the skills that are needed to do work accordingly. (SWP 1)

Real supervision provides support and guidance to social workers. It provides support to social workers. (SWP 9)

I would say it is the communication between the supervisee and the supervisor when the supervisor will provide guidance to the supervisee when it is needed and check whether everything is done in an acceptable manner. Any guidance needed by the supervisee has to be communicated by the supervisor. (SWP 10)

It is where you provide support to the employee... you educate and support them so that the employee can grow... Supervision must help an employee to develop professional maturity. Yeah, I can define it that way... you educate, you support the employee to develop professional maturity... (SWS 3)

While few participants described supervision in terms of education and growth, the above statements demonstrate that support and guidance emerged as the main features of supervision that should be evident in their practice. The participants' responses revealed that supervision should be characterised by the constant provision of the support and guidance that are necessary to stimulate professional growth and maturity and to ensure job satisfaction. The DSD and SACSSP (2012), through the Supervision Framework for the social work profession in South Africa, recognise the supportive functions of supervision that mainly assist in increasing job satisfaction and improving work morale. Schmidt and Kariuki (2019) explain that the supportive function of supervision contributes towards the elimination of work-related stressors and promotes healthy working conditions that contribute to increased job satisfaction. Guidance is offered to social workers in the supportive function as they work to enhance the provision of services to clients (McPherson & Macnamara, 2017).

Subtheme 1.2: Supervision as educational and growth-related process

Supervision is also regarded as a reflective process which provides an opportunity to enhance individualised personal and professional growth (Berger & Quiros, 2014; O'Neill & del Mar Fariña, 2018). In response to the same question about the conceptualisation of social work supervision, some participants stated the element of growth and development as another essential element in supervision. Participants' responses were as follows:

Supervision must have an element of growth and development of the supervisee. Now, it doesn't happen like that. It is all about submitting reports and meeting deadlines and does little that is needed to develop and grow an individual. Supervision also deals with educational development, but it doesn't happen. That's how I understand it. It must shape even the approach, behaviours, and attitudes of employees. (SWP 12)

For me, supervision is about educating supervisees on the work they need to do to ensure that they do it accordingly. I also think of supervision as a way to account for the work that you have been given. (SWP 5)

According to my understanding, we conduct supervision for an individual to grow in his/her profession. This takes me to the concept of what is supervision. According to what I've been trained on, supervision is a scientific and conscious process that you need to plan for and need to do as a supervisor to help the employee grow in the scope of work he or she is doing. (SWS 2)

The above comments indicate the views of participants on the significance of the growth and development of supervisees in supervision. As is noticeable from the participants' responses, supervision is also conceptualised as a process that is characterised by education through the provision of training for the purposes of empowerment and enhancement of skills. Kadushin and Harkness (2014) view the educational function as encompassing teaching, facilitation, clarifying, professional growth, informing and problem solving. Social workers and supervisors in this particular district thought that supervision should focus mainly on the educational function so as to achieve professional growth. For professional growth to be realised, it must be informed by the appropriate assessment of gaps in social workers' knowledge and skills as well as the understanding of current practice challenges (Schmidt & Kariuki, 2019).

Joubert, Hocking and Hampson (2013) mention that professional supervision is an integral component of social work practice, providing opportunities for case discussion and reflection, support and professional development. Participants view professional development and maturity as key to the effective delivery of services and, therefore, should be the key focus of supervision. Supervisors expressed concerns that supervision ends up becoming difficult to implement because supervision ratios become excessively escalated beyond what the Supervision Framework for the social work profession in South Africa prescribes. The high levels of cases from the clients of social workers also exert pressure on supervisors as the need for continuous supervision becomes a need for all social workers, especially when confronted with more complex cases. Participants were also requested to relate their understanding of supervision to their own experience.

Theme 2: Relating understanding of supervision to experience

Participants were asked to relate their conceptual understanding of supervision to their practical experience of supervision. The significance of exploring the participants' understanding of supervision on the basis of their experiences was to assist the researchers in arriving at an informed conclusion on whether there were commonalities among participants' understanding of supervision and whether these were based on their practical experiences or not. Most participants explained that their understanding of the nature of supervision is not related to their actual experience of supervision.

Subtheme 2.1: Understanding not similar to experience of supervision

As participants gave accounts of their experiences of social work supervision, it emerged that most of their understanding of what supervision is and what it should be was not related to what they experienced in practice daily. This discrepancy is evident in the participants' accounts as reported below:

I would say supervision has never been something that has made any positive impact on me, because it has never been a good thing or had an impact... I work independently I have never had an opportunity to be supervised genuinely. As I have said that I work independently, because rarely would you find the person who comes and supervises. At the end of the day, you have to work independently... theoretically we can say that things should be supposed to go this way, but practically I have to go my own way to get issues solved.... (SWP 13)

No, the supervision I have described is not what happens in this office, because they do not care about your problems, even those that relate to your cases or other duties... I have never had a one-on-one session with my supervisor except for those urgent short consultations. rather I use my senior social workers to provide me with guidance... (SWP 7)

The understanding is the same with the one we were taught in university, but when it comes to it being implemented, it is different because there are things that a supervisor is expected to do but that are impossible to do in this environment. I cannot do one-on-one with my supervisee; I cannot give them the support they need... all that is required, but I end giving them few minutes of my time when there are urgent cases... (SWS 2)

For supervision experience of supervisors and supervisees to be better, they have to revise the ratio of supervision in the framework. You will find that in the framework the ratio of a supervisor to supervisees is maybe 1:15 or 1:13, but that ratio is too high for supervision. You cannot provide effective supervision. Even if you really wish to do so, it becomes impossible when having other responsibilities. At least if you can say 1:5 or 1:6... so supervision ends up undoable.... I currently have 19 or 20 supervisees so that [is] the challenge, because I also have other duties expected of me. (SWS 1)

The participants' statements reflect the extent of the discrepancy in supervision practice between the conceptual and practical level. It is evident from the participants' accounts above that what they described and understood conceptually as supervision in social work is not what they experienced supervision to be on a day-to-day basis. The participants' accounts demonstrate that both social workers and supervisors describe supervision in their practice as non-existent. Hence, this deprives social workers of the chance to receive the necessary support for their work as well as of an opportunity to engage in reflective practice and consequently their ability to develop professionally (Maslow, 2020). The nature of the environment in which social workers and supervisors operate creates a situation that makes it difficult for both supervisors and social workers to translate into practice what they have been trained to expect regarding supervision. Alpaslan and Schenck (2012) found that social workers working in rural settings are confronted with conditions that are too hostile for an effective supervision process to unfold. Nevertheless, professional supervision can be highly advantageous for social workers in rural areas, as that would cushion them by providing constant support as they are mostly confronted with a high number of cases that are very diverse (Nickson, Gair & Miles, 2016; Sandu & Unguru, 2013). As a result of the lack of professional supervision, service delivery to clients remains compromised. Some participants also described their supervision experience as being partly in line with what they had understood supervision to be.

Subtheme 2.2: Supervision experience partly corresponds with the theory of supervision

There were social workers and supervisors who described their understanding of supervision as having little correlation with their practical experience of supervision as implemented in their practice. When participants were requested to provide their views, these accounts emerged, amongst others:

I would not say it is completely similar and I would not say it is completely different, because I think we have got a lot of workload. So, you will find that we consult supervisors, otherwise we figure things on our own, but they do give us that small support and guidance when we call for it. (SWP 12)

It is different partly because it is not functional due to the high caseload, because sometime you make plans on what you will need to do, but find that you are tasked to do other things... same with supervisors, [who] do make plans on what they will do but get disturbed... it is very much different in the Department on how it is done... sometimes you end up thinking that what you learnt in the university does not help you when it comes to its practicality. you even forget what it means to be a social worker. (SWP 6)

I think it is similar because when you have a problem you can consult with your supervisor and also get the information you need. (SWS 4)

The participants' assertions above indicate that their experiences of social work supervision in their service offices as being unreliable, inconsistent and unpredictable. The impact of such supervision practices yields unguaranteed and unmeasured outcomes to supervisees and clients. Holzinger et al. (2016) mention that in a context marked by less integration and harmonisation of state and traditional institutions, more negative consequences normally emerge. In the context of this study, the integration and harmonisation should unfold from the DSD as an institution founded upon democratic statutes and the deeply cultural and traditional institutions and communities that are served by social workers at the DSD service office level. These negative consequences of the disjuncture between the DSD and its surrounding traditional communities include a direct or indirect impact on the functioning of social workers with their clients as they aim to fulfil their professional and organisational mandate. Hair (2015:352) asserts that "it is the responsibility of supervisors to explore differences and local understandings of knowledge and values with social workers in order to have effective supervision relationships". It is evident that supervision is critical for social workers to foster the necessary growth, autonomy, support and guidance, and to develop the capacities to effectively confront unique challenges that may arise by functioning in this context.

DISCUSSION

A central feature of this study is the social workers' and supervisors' conceptualisation of supervision in the social services sector, which is characterised by the co-existence of managerial and professional supervision. The analogy of polity dualism has been used to explain the nature of this existence. This coexistence served as the thread that cuts across to explain the context of supervision and its influence on implementation supervision. It is evident from the data collected that the coexistence plays a huge role on how social workers conceptualise and experience the practice of social work supervision in this district.

In summary, the findings reflect that the implementation of social work supervision still remains a major challenge in the DSD with a highly managerialist approach taking precedence over professional supervision. The implication of supervision being mainly managerial is that professional supervision is neglected, and subsequently the educational and supportive functions are minimised. Compared to professional supervision, managerial supervision is viewed as largely influenced by external factors that impact on the organisation.

This not only creates a major gap in practice, but also leads to ineffective practice for social workers. Although in the findings of this study, the participants described the implementation of supervision in the social service organisation as still being a challenge, they still regard it to be important and believe that it is necessary to provide them with support, guidance, education and foster growth. The findings are roughly congruent with the analogy of polity dualism in supervision, as the practice of managerial supervision is seen as the traditional mode of supervision and still takes precedence over professional supervision, which is seen as a democratic mode of supervision which allows for active participation and critical reflective practice.

Secondly, the influence of the socio-political factors on social services and supervision cannot be underestimated. These influences may be indicative that supervision is "not a politically innocent" phenomenon and that it is susceptible to external influences (Adamson, 2012:194). High caseloads were highlighted by participants as one of the issues that impact of the implementation of supervision in DSD at King Cetshwayo District. These findings are similar to the ones reached by other scholars (Dlamini & Sewpaul, 2015; Manthosi & Makhubele, 2016; Shokane, Makhubele, Shokane & Mabasa, 2017). Common among the related studies is the depiction of the high caseloads of social workers and supervisors and the impact of this on their responsibilities, the high supervisor-supervisee ratio and job dissatisfaction.

Thirdly, Dlamini and Sewpaul (2015) highlighted the implications of neoliberalism and its relationship to managerial supervision as contributing to the erosion of the core of the profession's identity. With the unique challenge that polity dualism presents in the DSD at King Cetshwayo District, social workers require extended support and guidance from their supervisors to navigate complex and demanding cases that may stem from the clients' deeply held cultural and traditional orientations. However, some African scholars have emphasised that the provision of supportive supervision needs to take into account the unique socio-cultural context of each locality, so that it can promote professional development and service delivery to clients (Gumbi, 2021; Mendenhall, De Silva, Hanlon, Petersen, Shidhaye, Jordans., Luitel, Ssebunnya, Fekadu, Patel & Tomlinson, 2014; Ncube, 2016; Ross & Ncube, 2018). Furthermore, Nickson, Cater and Francis, (2020:5-6) assert that the "impact of social work supervision on social workers depends on the supervisor's cultural sensitivity and ability to be contextually relevant as well as whether supervision is conducted in a more humanistic manner".

Despite the limitations of the clear articulation of African-centred supervision in South Africa, this article acknowledges that the meaningful strides made in the literature and practice related to indigeneity, Africanising, decolonising and decoloniality of social work practice lays a critical foundation for African-centred supervision. Moreover, the need for extensive literature on social work supervision with specific reference to the African context cannot be over-emphasised as this would lay the foundations for new Afrocentric literature on supervision. African scholarship on supervision would provide a unique perspective on how supervision should be carried out in a context characterised by high levels of polity dualism.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Three recommendations worth noting in this article may be summarised as (i) adherence to the policy framework, (ii) capacity building and (iii) the development of new supervision practices. Firstly, it is recommended that supervisors adhere to a supervisory-related policy framework. The Supervision Framework for the social work profession in South Africa (DSD & SACSSP, 2012) stipulates the roles and responsibilities and the prescribed supervisor-supervisee ratio, to name a few aspects. Adherence to these provisions would strengthen the supervision process in the service offices, and afford time and space for social workers to be supervised across the three supervision functions. Having supervisors who focus only on supervision would assist social workers to receive much needed support when confronted with uniquely complex cases emanating from the demanding contexts within which they are employed. There is a need to find innovative ways to decrease the administrative duties for social workers and supervisors. This may assist in better managing the high caseloads that pertain to clients. This would ensure that each client's case would be dealt with more efficiently.

The second recommendation is the provision of ongoing capacity-building support for both supervisors and social workers, even before the latter assume a supervisory role. This is relevant considering that supervision is a relational process. Supervision education and training are also fundamental for the successful implementation of quality and effective supervision. This is because, as Schmidt and Kariuki (2019) assert, the social work curriculum on the undergraduate levels of study reflects generalist practice and educates social work students on social policy, ethics and values, and basic practice methods, but it lacks supervision training as an important dimension of social work practice. Furthermore, to assist social work supervisors confront challenges presented by polity dualism, it is recommended that they practise professional supervision that would enable their supervisees to constantly engage in reflective practice.

Lastly, the widened interest in social service organisations and supervision practice in contemporary society could dictate the development of new ideas of designing and executing supervision practices as opposed to adherence to the traditional ways. As indicated in Hafford-Letchfield and Engelbrecht (2019), the key stakeholders in supervision extend beyond the immediate supervisor-supervisee relationship, and include service users, educators, people leading and managing services, and organisations providing services. Social workers and social work supervisors as key role players in supervision are required to develop deeper engagement and reflection not only on their experiences, but with due consideration of the influence of socio-political factors on social service organisations within the context in which supervision is taking place (Mo & Tsui 2019; Rankine, 2019; Roche, 2022). The contemporary literature and research on supervision practice locally and internationally is likely to assist in strengthening the practice of supervision.

REFERENCES

Adamson, C. 2012. Supervision is not politically innocent. Australian Social Work, 65(2): 185-196. Doi:10.1080/0312407X.2011.618544. [ Links ]

Alpaslan, N. & Schenck, R. 2012. Challenges related to working conditions experienced by social workers practising in rural areas. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(4): 400-419. https://doi.org/10.15270/48-4-24. [ Links ]

Amankwaa, L. 2016. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 23(3): 121-127. [ Links ]

Beddoe, L. 2015. Supervision and developing the profession: One supervision or many? China Journal of Social Work, 8(2): 150-163. doi:10.1080/17525098.2015.1039173. [ Links ]

Berger, R. & Quiros, L. 2014. Supervision for trauma-informed practice. Traumatology, 20(4): 296-301. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099835. [ Links ]

Bloomberg, L. D. & Volpe, M. 2019. Completing your qualitative dissertation: A road map from beginning to end. 4th ed. Los Angeles: London [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2): 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Caras, A. & Sandu, A. 2014. The role of supervision in professional development of social work specialists. Journal of Social Work Practice, 28(1): 75-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2012.763024 [ Links ]

Caspi, J. & Reid, W. L. 2002. Educational supervision in social work: A task-centred model for field instruction and staff development. New York: Colombia University Press. [ Links ]

Chibaya, N. H. & Engelbrecht, L. K. 2022. What is happening in an individual supervision session? Reflections of social workers in South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 58(4): 520-545. https://doi.org/10.15270/58-4-1079 [ Links ]

Clark-Kazak, C. 2017. Ethical considerations: Research with people in situations of forced migration. Refuge, 33(2): 11-17. [ Links ]

Connelly, L. M. 2016. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing, 25(6): 435-436. [ Links ]

Crabtree, B. F. & Miller, W. L. 2022. Doing qualitative research. 3rd ed. California: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Daniel, J. 2012. Sampling essentials: Practical guidelines for making sampling choices. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

De Groot, S. 2016. Responsive leadership in social services: A practical approach for optimizing engagement and performance. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development (DSD) & South African Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSP). 2012. Supervision framework for the social work profession in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Dlamini, T. T. L. & Sewpaul, V. 2015. Rhetoric versus reality in social work practice: Political, neoliberal and new managerial influences. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 51(4): 467-481. https://doi.org/10.15270/51-4-461 [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, L. K. 2010. Yesterday, today and tomorrow: Is social work supervision in South Africa keeping up? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 46(3): 324-342. https://doi.org/10.15270/46-3-162. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, L. K. 2013. Social work supervision policies and frameworks: Playing notes or making music? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(4): 456-68. https://doi.org/10.15270/49-3-34 [ Links ]

Gelling, L. H. 2016. Applying for ethical approval for research: The main issues. Nursing Standard, 30(20): 40-44. Doi: 10.7748/ns.30.20.40.s46 [ Links ]

Gumbi, S. N. 2021. Exploring the experiences of social work practitioners and supervisors on the implementation of social work supervision in the Department of Social Development: A case study of King Cetshwayo District Municipality. Master's thesis. University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Hafford-Letchfield, T. & Engelbrecht, L. 2019. Introduction. In: Hafford-Letchfield, T. & Engelbrecht, L. (eds.). Contemporary practices in social work supervision: Time for new paradigms? (pp. 1-5). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hair, H. J. 2015. Supervision conversations about social justice and social work practice. Journal of Social Work, 15(4): 349-370. https://doi.org/10.1177/146801731453908. [ Links ]

Hawkins, P. & Shohet, R. 2012. Supervision in the helping professions. 4th ed. New York: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Holzinger, K., Kern, F. G. & Kromrey, D. 2016. The dualism of contemporary traditional governance and the state: Institutional setups and political consequences. Political Research Quarterly, 69(3): 469-481. Doi: 10.1177/106591291664801. [ Links ]

Joubert, L., Hocking, A. & Hampson, R. 2013. Social work in oncology - Managing vicarious trauma: The positive impact of professional supervision. Social Work in Health Care, 52(2-3): 296-310. Doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.737902. [ Links ]

Kadushin, A. & Harkness, D. 2014. Supervision in social work. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Kamanzi, A. & Romania, M. 2019. Rethinking confidentiality in qualitative research in the era of big data. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(6): 743-758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219826222 [ Links ]

Karvinen-Niinikoski, S., Beddoe, L., Ruch, G. & Tsui, M. 2019. Professional supervision and professional autonomy. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31(3): 87-96. [ Links ]

Khosa, P. 2022. Implementation of the supervision framework for the social work profession in South Africa by a designated child protection organisation. Doctoral thesis. Stellenbosch University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Krysik, J. 2018. Research for effective social work practice. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mahat-Shamir, M., Neimeyer, R. A. & Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S. 2021. Designing in-depth semi-structured interviews for revealing meaning reconstruction after loss. Death Studies, 45(2): 83-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1617388 [ Links ]

Manthosi, F. L. & Makhubele, J. C. 2016. Impact of supervision on social worker's job performance: Implications for service delivery. SAAPAM Limpopo Chapter 5th Annual Conference Proceedings. Polokwane: University of Limpopo. [ Links ]

Maslow, A. 2020. Social work supervision. In: Nickson, A. M., Carter, M. & Francis, A. P. (eds.). Supervision and professional development in social work practice. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt LTD. [ Links ]

McPherson, L. & Macnamara, N. 2017. Supervising child protection practice: What works? An evidence informed practice. Cham: Springer. [ Links ]

Mendenhall, E., De Silva, M. J., Hanlon, C., Petersen, I., Shidhaye, R., Jordans, M., Luitel, N., Ssebunnya, J., Fekadu, A., Patel, V. & Tomlinson, M. 2014. Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: Stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. Social Science & Medicine, 118(2014): 33-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.057 [ Links ]

Mo, K. Y. & Tsui, M. S. 2019. Toward an indigenized external supervision approach in China. International Social Work, 62(4): 1286-1303 Doi: 10.1177/0020872818778104 [ Links ]

Ncube, M. 2016. Conceptualizing social development supervision in social work. The Indian Journal of Social Work, 80(1): 31-46. Doi: 10.32444/ijsw.2018.80.1.31-46. [ Links ]

Nickson, A., Gair, S. & Miles, D. 2016. Supporting isolated workers in their work with families in rural and remote Australia: Exploring peer group supervision. Children Australia, 41(4): 265-274. Doi:10.1017/cha.2016.41 [ Links ]

Nickson, A. M., Cater, M. A. & Francis, A. P. 2020. Supervision and professional development in social work practice. Los Angeles: SAGE publications. [ Links ]

O'Neill, P. & del Mar Fariña, M. 2018. Constructing critical conversations in social work supervision: Creating change. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46(4): 298-309. Doi: 10.1007/s10615-018-0681-6 [ Links ]

O' Donoghue, K. & Engelbrecht, L. 2021. Introduction: Supervision in social work. In: O' Donoghue, K. & Engelbrecht, L. (eds.). The Routledge international handbook of social work supervision. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Patel, L. 2019. Social development, management and supervision of social workers. In: Engelbrecht, L. K. E. (ed.). Management and supervision of social workers. 2nd ed. Hampshire: Cengage Learning, EMEA. [ Links ]

Patel, M. & Patel, N. 2019. Exploring research methodology: Review article. International Journal of Research & Review, 6(3): 48-55. https://doi.org/10.4444/ijrr.1002/1004. [ Links ]

Phungwayo, M. 2012. The performance management system of the Department of Social Development in enhancing the delivery of social services. Master's thesis. University of Witwatersrand, South Africa. [ Links ]

Pietilä, A. M., Nurmi, S. M., Halkoaho, A. & Kyngäs, H. 2020. Qualitative research: Ethical considerations. In: Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K. & Kääriäinen, M. (eds.). The application of content analysis in nursing science research (pp.49-69). Cham: Springer. [ Links ]

Rankine, M. 2019. The 'thinking aloud' process: A way forward in social work supervision. Reflective Practice, 20(1): 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1564651 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Government Gazette, Vol. 378, No. 17678. (8 May 1996) Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1997. Ministry of Welfare and Population. White Paper for Social Welfare. Notice 1008 of 1997. Government Gazette, Vol. 368, No. 18166. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Roche, C. 2022. Decolonising reflective practice and supervision. Philosophy of Coaching: An International Journal, 7(1): 30-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.22316/poc/07.L03. [ Links ]

Ross, E. & Ncube, M. 2018. Student social workers' experiences of supervision. Social Sciences, 79(1): 31-54. Doi: 10.32444/IJSW.2018.79.1.31-54 [ Links ]

Sandu, A. & Unguru, E. 2013. Supervision of social work practice in North-Eastern Romanian rural areas. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 82: 386-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.280 [ Links ]

Schmidt, G. & Kariuki, A. 2019. Pathways to social work supervision. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(3): 321-332. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1530160. [ Links ]

Shokane, F. F., Makhubele, J. C., Shokane, A. L. & Mabasa, M. A. 2017. The integrated service delivery model challenges regarding the implementation of social work supervision framework in Mopani District, Limpopo Province. International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA), 278-287. [ Links ]

Singh, S. & Wassenaar, D. R. 2016. Contextualising the role of the gatekeeper in social science research. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 9(1): 42-46. Doi: 10.7196/SAJBL.2016.v9i1.465 [ Links ]

Sithole, M. S. 2020. The first-time supervisors' experiences of power relations in social service professions: Case study of social work supervisors in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration and Development Alternatives, 5(2): 68- 80. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-jpada-v5-n2-a6 [ Links ]

Sithole, M. S. & Shokane, A. L. 2023. Workplace learning in the contemporary supervision landscape: The case of supervision in a social service organisation. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 59(2): 127-149. Doi: 10.15270/59-2-1125. [ Links ]

Spolander, G. 2019. The impact of neoliberalism on management and supervision. In: Engelbrecht, L. K. E. (ed). Management and supervision of social workers: Issues and challenges within a social development paradigm. 2nd ed. (pp.278-287). Hampshire: Cengage Learning, EMEA. [ Links ]

Tropman, F. E. 2022. Managerial supervision. Encyclopedia of Social Work, 20: 01-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1511. [ Links ]

Ubink, J. & Duda, T. 2021. Traditional authority in South Africa: Reconstruction and resistance in the Eastern Cape. Journal of Southern African Studies, 47(2): 191-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2021.1893573 [ Links ]

Vetfuti, N., Goliath, V. M. & Perumal, N. 2019. Supervisory experiences of social workers in child protection services. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 31(2): 1-18. [ Links ]

White, V. 2015. Reclaiming reflective supervision. Practice, 27(4): 251-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1048055 [ Links ]

Wong, P. Y. J. & Lee, A. E. Y. 2015. Dual roles of social work supervisors: Strain and strengths as managers and clinical supervisors. China Journal of Social Work, 8(2): 164-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17525098.2015.1039168. [ Links ]

Article received: 16/8/2022

Article accepted: 18/08/2023

Article published: 26/03/2024

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Sandile Ntethelelo Gumbi is a PhD candidate and a contract Lecturer at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in the discipline of Social Work. His research focus is mainly, on Social Work Supervision, Decoloniality and Afrocentricity. Mr Gumbi conducted a Masters study from January 2019 to December 2021, and that is the study on which the article is based. He was responsible for conceptualising the article and led the process, including collating the activities and liaison with the Journal.

Ntombifîkile Mazibuko is a Professor Emeritus at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, also serves as an Interim Senior Director in the office of Pro Vice-Chancellor: Student Services, leading the Project Renewal of the institutional student support services. Prof Mazibuko specialises in social development, social policy, management administration and leadership. She contributed from the conceptualisation to the finalisation of the article, including interpretation of findings.

Mbongeni Shadrack Sithole is a senior lecturer in the Department of Social Work in the School of Applied Human Sciences at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. His research interests involve Afrocentricity, decoloniality, management and administration and inclusive education. He supervised the study and assisted with the drafting of the article.