Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.60 n.1 Stellenbosch 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/60-1-1256

ARTICLES

IsiZulu-speaking caregivers' perceptions on disclosing child sexual abuse

Douglas MavhungaI; Pieter John BoshoffII

INorth-West University, COMPRES, School of Psychosocial Health, Potchefstroom, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9710-4927 dougmav@gmail.com

IINorth-West University, COMPRES, School of Psychosocial Health, Potchefstroom, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4560-4337 Pieter.Boshoff@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Child sexual abuse affects children and caregivers all around the world. According to the South African Police Service's (2020/21) crime statistics report, child sexual abuse is common in South Africa, particularly the township of Tsakane. Tsakane, located in Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, is predominantly comprised of IsiZulu-speaking residents and has a significant child sexual abuse problem. Child sexual abuse may be perceived differently by IsiZulu-speaking caregivers than by other cultural groups and hence a qualitative study was carried out to explore this phenomenon. The study employed an exploratory design and semi-structured individual interviews. Thematic content analysis was conducted in analysing the data. The findings revealed that isiZulu caregivers in Tsakane are hesitant to report incidences of child sexual abuse because of cultural, environmental and psychological cost factors. This means that social work should address child sexual abuse in a comprehensive, culturally sensitive and community-focused manner.

Keywords: caregiver; child sexual abuse; culture; disclosure; isiZulu

INTRODUCTION

Assume you are the caregiver for a child who has lately confessed to being sexually abused. Hearing such a disclosure can be emotionally demanding, especially for caregivers who may not have received proper training in coping with such situations. This is exacerbated by the fact that discussing sexual abuse is considered a taboo in some cultures, including IsiZulu-speaking communities, perpetuating a cycle of silence and humiliation. Child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosure is an important element of the healing process for CSA victims.

Disclosure is defined by Pipe, Lamb and Orbach (2013:65) as "the process by which a victim gradually notifies others about their abuse." According to the authors, victims of CSA are often hesitant to talk about their experiences, but they may be more inclined to confess once they have gained the trust of a caregiver or other trusted individual. The term "caregiver" refers to someone who provides actual care for a child but who is not their parent or guardian. Foster parents, individuals caring for a child with consent from the parent or guardian, those providing temporary safe care, heads of child and youth care centres or shelters where a child is placed, child and youth care workers caring for children without appropriate family care, and children who are the heads of child-headed households are all included in this category of "caregiver" (Section 1.1 of the Children's Act No 38 of 2005, 11-12, Republic of South Africa [RSA], 2006). This indicates that caregivers can play a key role in providing a secure and supportive environment for CSA victims to share their experiences and begin the healing process.

Understanding the perceptions of IsiZulu-speaking caregivers of CSA disclosure is therefore crucial in breaking the cycle and ensuring that children receive the required assistance and care. Caregivers' perceptions about CSA can have far-reaching consequences. Some caregivers believe that children should keep silent about the abuse to prevent bringing shame to their families or communities, while others believe that disclosing the abuse will result in more harm to the child or themselves. These fears and beliefs may cause the abuse to go unreported or be reported too late. Early disclosure and intervention, according to Alaggia, Collin-Vézina and Lateef (2019), can be critical in mitigating the impacts of CSA. Understanding the perceptions of IsiZulu-speaking caregivers is therefore crucial in developing successful interventions that take cultural beliefs and practices into account.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

South Africa promulgated the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006), as amended, to defend children's rights to physical health, mental wellbeing and education (Colgan, 2009). CSA, however, is a widespread problem that affects children of all socioeconomic backgrounds, nationalities, ethnicities, beliefs and genders (Artz, Ward, Leoschut, Kassenjee & Burton, 2018).

The South African Police Service's (2019/2020) annual crime statistics, reflect a highly concerning situation regarding child sexual abuse in South Africa. According to this discouraging data, over 24,000 children were victims of sexual abuse during that period, underlining the troubling truth that one in every five children endured this painful experience. The local prevalence surpasses the global averages for girls (18%) and boys (8%), as reported by Gcwabe and Gwala (2021). The frightening finding that many of these heinous acts are carried out by family members or individuals linked with the victim's family, often in secrecy, adds to the depth of the problem (Pijoos, 2017). Furthermore, the South African Medical Research Council reports that less than 4% of CSA cases in the country are reported to authorities, therefore estimates may vastly understate the scope of the problem.

Section 18 of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006), as amended, addresses the vital issue of parental responsibilities and rights, with a focus on reinforcing and conserving family structures, and in this regard caregivers play an important role in defending children's best interests in all situations (De Villiers, 2014).

Section 110 of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006), as amended, also stipulates that caregivers must report any form of child abuse they become aware of in a certain manner.

However, caregivers frequently confront obstacles that impede CSA disclosure. Single mothers, and particularly grandparents, are the primary carers, and they lack community support as well as trust in government authorities to solve problems (Xaba, 2021). Formal services may be inaccessible or ineffective, leading caregivers to report the abuse to community authorities in the hope that the perpetrator will face some form of retaliation (Meinck, Cluver, Boyes & Loening-Voysey, 2016). Despite the importance of social workers in families and communities, some caregivers do not have easy access to them.

In some cases, caregivers may choose to protect the perpetrator, particularly if the perpetrator is the family breadwinner. Furthermore, some caregivers may be unwilling to disclose abuse because of concern for the family's reputation in the community (Rapholo, 2014). Additionally, caregivers are not always able to recognise the fundamental reason of sexualised behaviour in children or know what steps to take. The caregiver's own emotional state and life experiences can have an impact on how they perceive and respond to a child's needs (Faller & Everson, 2014).

Gorman and Anwar (2019) assert that what defines CSA differs depending on cultural norms and beliefs. Different cultural groups may interpret sexual abuse in different ways, resulting in misconceptions and underreporting of CSA. Culture is not static and can change over time, leading to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of people's conduct. Understanding the cultural environment in which CSA occurs is critical to properly addressing the problem (Yearwood, Pearson & Newland, 2012).

Sexual abuse is rampant in Tsakane, a predominantly isiZulu-speaking town in Gauteng. Rape cases have significantly increased in the community, with Tsakane Police Station being among the top 10 in the country based on crime statistics for 2021/2022 (Cele, 2022). However, the publicly available provincial statistics on sexual abuse do not differentiate between abuse of women and of children, making it difficult to determine the extent of child rape in the community. As a result, the data may not fully reflect the extent or seriousness of child rape (Pijoos, 2017).

In modern society, IsiZulu-speaking people place a great emphasis on preserving cultural norms, rituals and values that they believe distinguish them from other cultures (Meinck et al., 2016). This need for cultural preservation may lead to misconceptions about how caregivers in this culture perceive CSA. Rape is the only type of CSA that is widely recognised as reportable in many cultures, and other forms of abuse may not be reported owing to variance in perception. These cultural views may play a role in the high rates of non-disclosure of CSA (Clark, 2015). As a result, it is possible to argue that CSA and the degree of its disclosure may have culturally unique manifestations that differ across African cultural groups.

There has been limited research on caregivers' disclosure of CSA in African communities. Previous research by Hendricks (2014) and Meinck et al. (2016) explored post-abuse services and mandatory disclosure of CSA in general. Other research (Marais, 2022; Ramphabana, Rapholo and Makhubele, 2019; Rapholo, 2014; Zantsi, 2014) examined caregiver attitudes towards CSA disclosure among the isiXhosa, Pedi and Vhavenda ethnic groups. According to the research, fear of the offender, the spirit of ubuntu, socioeconomic position, relationship with the perpetrator, preserving family dignity, fear of victimization, fear of witchcraft, and cultural beliefs are among the factors that influence the level and nature of disclosure. However, because of their narrow emphasis, these findings have limited applicability.

The researchers intended to address the research gap by focusing on isiZulu-speaking caregivers in Tsakane, which has a high rate of sexual abuse and a high prevalence of isiZulu-speaking people. By exploring isiZulu-speaking people's perceptions from a culturally diverse perspective, the researchers seek to better support and empower caregivers and survivors of CSA in a culturally sensitive manner, particularly for social workers working in diverse cultural contexts.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The study is based on Bandura's (1986) social cognitive theory (SCT), which posits that learning occurs in a social setting through dynamic and reciprocal interactions between individuals, their environment and their behaviour. The research focuses on the role of observation, modelling and learning in moulding people's views and behaviours. Using this paradigm, the study investigates the influence of personal experiences, cultural norms and social learning on IsiZulu-speaking caregivers' views on CSA disclosure.

THE AIM OF THE RESEARCH

The aim of the research study was to explore the perceptions of isiZulu-speaking caregivers regarding the disclosure of CSA.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The researchers used a qualitative exploratory methodology to acquire a better understanding of caregivers' perceptions regarding disclosing occurrences of CSA amongst isiZulu-speaking people. According to Rendle, Abramson, Garrett, Halley and Dohan (2019), a qualitative-exploratory approach enables researchers to delve into understudied areas and allows participants to contribute to the production of new knowledge in that field. The study focused on isiZulu-speaking caregivers in Gauteng's Tsakane community, who had received CSA education through empowerment and awareness campaigns. Purposive sampling, a non-probability sampling technique, was used in this study, with defined selection criterion serving as the foundation for sampling (Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls & Ormstrong, 2014). Consequently, the sample included caregivers who spoke isiZulu, were informed about CSA in the Tsakane Community because of their exposure to empowerment and awareness initiatives offered by the Department of Social Development (DSD), and were able to articulate their views on CSA disclosure.

Data saturation was achieved after 15 participants were interviewed. Participants included isiZulu-speaking caregivers between the ages of 18 and 70, of both genders, and with knowledge of CSA in the Tsakane Community. The researcher performed individual face-to-face interviews, using a semi-structured interview schedule and a list of preset open-ended questions to guide the interview process. The data-collection method allowed for thorough probing and exploration. The following interview schedule was employed by the researcher:

• What are your thoughts about CSA among isiZulu-speaking people in the Tsakane Community?

• How do you perceive the disclosure of CSA?

• How should a child's caregiver participate to the disclosure of sexual abuse of the child?

• What are the reasons for isiZulu-speaking caregivers' failure to disclose CSA?

• Do you have any suggestions for encouraging caregivers to report CSA?

The eight-step data-analysis process described by Tesch (1992) was utilized. The researcher read through all the transcripts several times to become acquainted with the data. Field work, researcher notes and observations were used to drive the coding process, as proposed by Babbie (2016). Significant themes were identified, and related perceptions and concepts were arranged with headings and sub-headings to generate data coding (Creswell, 2014). The data were subjected to thematic analysis as is common in qualitative research (Creswell, 2014). The researcher then created integrated descriptions of the phenomenon that were divided into themes and sub-themes. This data visualisation facilitated discussion, debate and comparison with other studies and literature.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The research study received ethical approval from the Health and Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the North-West University's Potchefstroom Campus, with ethics number NWU-00489-19-A1. The researcher had formal discussions with several ward councillors to negotiate entry into the Tsakane Community. The social work supervisors from DSD and Child Welfare, responsible for the Tsakane Community, also gave their consent. The ethical risk associated with the study was moderate, as discussing CSA could trigger emotional responses and memories for caregivers. All participants signed a confidentiality declaration which ensured their anonymity and confidentiality throughout the data collection, analysis and storage process. Numbers were assigned to the participants to conceal their identities, and digital recordings were used only for transcription before being deleted. Electronic data were stored on the researcher's password-protected computer, and access to locked cabinets containing transcripts was limited to the researchers. Participants were informed about the purpose and scope of the research, and reminded of their voluntary participation in both English and isiZulu by an independent person before they granted informed consent. Consent was granted in the presence of an independent person and a witness, either at the organisations' offices or the participants' residences. Participants experiencing emotional distress were referred to social workers from DSD or Child Welfare in the Tsakane community for assistance in coping.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

The study included 15 caregivers, with only two of them being men and the rest being women. This is consistent with a recent study by Horowitz, Parker, Graf and Livingstone (2017), which found that women are more likely to be child caregivers. Most of the participants (61%) were young persons aged 19 to 35, with only 13% above the age of 60. The study included caregivers of all ages between the ages of 18 and 70, but the higher percentage of young people could be attributed to the purposive sample strategy used, in which young individuals were disproportionately selected based on the inclusion criteria. As a result, the study's findings may be more representative of the perceptions of women and young people.

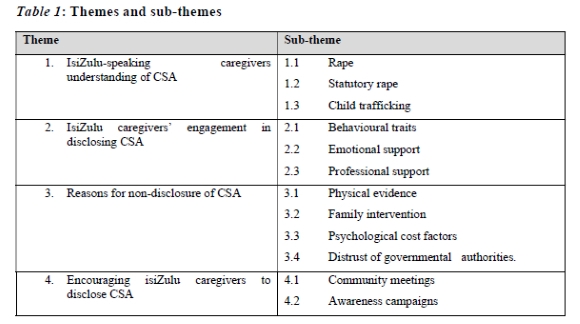

The analysis examines the themes and sub-themes derived from the data, as well as participant testimonies supported by relevant literature. The researchers have limited the use of verbatim comments to two or three per theme or sub-theme, selecting those that most fully support the specific theme or sub-theme under consideration. This methodology ensures a thorough and concise representation of participants' points of view. The primary themes and related sub-themes from the research study are depicted in Table 1.

Theme 1: IsiZulu-speaking caregivers' understanding of CSA

CSA perceptions led to the development of various sub-themes, such as CSA as rape, statutory rape and child trafficking. These sub-themes will be discussed in depth below.

Sub-theme 1.1: Rape

Kim, Cho, Choi, Lee and Lee (2017:612) define child rape as "committing forced sexual intercourse by violence or threat on a child under the age of consent by an adult or an older child." It can cause severe and long-term physical, emotional and psychological damage to the victims, leaving them feeling helpless, fearful and distressed. This understanding is supported by the participants' verbatim accounts:

CSA is when an adult male uses his penis to forcefully penetrate the vagina of a girl child. This can be very traumatic; the child doesn't know how to cope.

CSA is when an adult male sleeps with a small child who does not know anything about sex, without the child's consent.

The adult male will have sexual intercourse with a little girl. This is rape and should be reported to the authorities.

CSA is viewed as violent conduct in the isiZulu culture in that an adult male penetrates a young girl's vagina without her consent. Victims of this type of abuse are more likely to report the crime. Participants' definitions of CSA includes only adult male perpetrators and vaginal penetration. This viewpoint supports the findings of Amoah, Gyasi and Halsall (2016), who concluded that culturally sexual encounters are frequently portrayed as a conflict between males and girls. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offenses and Related Matters) Amendment Act 5 of 2015 (RSA, 2015), on the other hand, makes no distinction between the genders of the victim and perpetrator when it comes to engaging in sexual contact with a complainant. Furthermore, the Act covers other forms of CSA that the participants did not name, such as sexual grooming, exposure to or display of pornography, employing children for pornographic purposes, or profiting from child pornography.

Aside from legal consequences, child rape can have long-term and severe implications for the victim, such as physical damage, psychological trauma, and difficulty with interpersonal connections and sexual functioning (Haskell & Randall, 2019). Child rape victims may require continuing care and therapy to address the trauma and begin to heal.

Sub-theme 1.2: Statutory rape

Sexual activity with a minor who has not achieved the age of consent is forbidden in isiZulu culture. This includes cases where the minor appears to voluntarily consent to the sexual activity. Despite the minor's obvious desire, the adult can nevertheless face statutory rape charges (Sadiki, 2022). The following statements are examples of the participants' points of view:

There are many cases where adults get involved in an intimate relationship with a child without anyone noticing it.

Some adult men do not see anything wrong being involved in sexual relationships with young girls around 14 and 15, especially girls from poor families since they help them financially.

Some participants believe that adult men having sexual intercourse with adolescent girls under the age of 16 is acceptable in isiZulu society, and that these girls are sexually active despite their age. Consensual sexual behaviour with adolescents aged 12 to 16 years old is criminalised by the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 5 of 2015 (RSA, 2015). There are exceptions if the perpetrator is under the age of 16, or the age difference between the perpetrator and a child is less than two years. Some stories have been shared about parents encouraging their children to marry because financial constraints force families to approve such relationships. The following comment is an illustration of this.

In some cases, an adult impregnates a child and forcefully takes the child as his wife. In such cases the adult would pay the family, traditional "ilobolo", so that the family can accept the young girl to live with the adult man. Parents sacrifices the child for money.

Forced child marriages, according to Efevbera and Bhabha (2020), are a worldwide problem that has significant consequences for young girls who are forced to give up their childhood for a life of abuse and illness. Poverty is a maj or cause of child marriage, since it provides financial respite for many destitute families who now have one fewer person to care for. According to Budoo and Ramnauth (2018), child marriage is common in South Africa with 1% of girls under the age of 15 married in South Africa. Traditional ukuthwala is a form of gender-based abuse or a damaging cultural practice in which girls as young as 12 are married off to older men.

Karimakwenda (2013) explains that this practice is frequently justified by the fact that the parents receive cash or gifts, which is a modified form of the traditional ilobolo or dowry practices.

Ukuthwala is a harmful cultural practice in South Africa. It is unlawful and infringes on human rights. It's distinct from the traditional ilobolo or dowry rituals, which entail the groom or his family giving the bride's family money as a token of respect and gratitude. South African law prohibits adults from having sex with adolescents who are under the age of consent, on the basis of their lack of maturity and experience to make informed decisions.

Sub-theme 1.3: Child trafficking

South Africa has become an attractive destination for human traffickers, serving as a source, transit point and destination for child trafficking (Rantao & Tshabalala, 2022). Children are kidnapped from secure locations and taken to other countries for sexual exploitation. Some participant comments are listed below.

Children in the rural areas in KwaZulu-Natal are lured with alcohol and/or drugs by adult men who visit those areas during holidays, and they end up coming with the men to Gauteng. These girls end up in prostitution, moving from one man to the other as they don't know anyone here.

Some Zulu men also transport young girls from rural Natal and marry them here in Gauteng. Typically, females drop out of school and follow these men in search of a better life in Gauteng.

Trafficked minors from KwaZulu-Natal are being lured by the promise of a better life and brought to Gauteng, where they often become victims of prostitution and drug abuse. The lack of employment and resulting poverty make people vulnerable to exploitation, as seen in research by Van Aswegen (2022) and Wrigley-Asante, Owusu, Otneng-Ababio and Owusu (2016). Impoverished children from Gauteng and the Western Cape are frequently taken to urban areas for exploitation by more affluent individuals. Disturbingly, criminal syndicates have even kidnapped children as young as 10 years old, drugging them and forcing them into prostitution.

According to Section 4(1) of the Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act No. 7 of 2013 (RSA, 2013), trafficking in persons includes various actions such as delivering, recruiting, transporting, harbouring and selling others through threats, coercion, deception, abduction, abuse of power, or by offering or receiving payments or benefits. This provision aims to combat the serious felony of human trafficking and deter such criminal activity.

The isiZulu culture regards child trafficking as repugnant conduct that contravenes the core values of ubuntu. which emphasises the interdependence and connectedness of all people (Msuya, 2017). In the isiZulu culture, children are seen as a gift from the ancestors and are greatly revered. Therefore, any kind of child abuse or exploitation is a serious injustice.

Theme 2: IsiZulu caregivers' engagement in disclosing CSA

Recognising CSA involves caregivers noticing changes in the child's mood, behaviour or physical health (Vaplon, 2015). Providing empathetic and encouraging feedback to the child can help them feel heard and believed, which is essential for the healing process. Caregivers can also assist the child by observing their actions, offering emotional support and seeking professional help.

Sub-theme 2.1: Behavioural traits

IsiZulu speaking children who have experienced sexual abuse exhibit troubling behavioural traits such as social disengagement, difficulty sleeping, changes in food habits, mood swings and reluctance to discuss the abuse. Caregivers need to address these patterns promptly. Some of the comments made by participants include the following:

I noticed that my child's academic progress deteriorated. It got me worried as I know that my child can read and write properly. She was no longer focused and lost interest in her schoolwork.

I realised that my child was now preferring to eat in her bedroom. She was avoiding being with people.

My child did not want to go play at the grounds. She would always ask me to go watch her play, she looked depressed.

Participants reported that people in the isiZulu culture have close relationships with the children they care for and are familiar with their daily routines. As a result, they are able to see behavioural changes that might point to sexual abuse. The participants voiced concern that the academic achievement of the children had dropped, they had grown more reclusive, and they were displaying signs of melancholy and restlessness. Odhayani, Watson and Watson (2013) stated that it is crucial to provide children with attentive care to detect early symptoms of sexual abuse, such as rapid mood swings, violent behaviour or withdrawal.

Negative emotional and physical symptoms in sexually abused children can include low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, stress and unexplained injuries (Fortinash & Holoday Worret, 2014). Caregivers must be aware of the warning signs and symptoms of CSA to encourage disclosure and take appropriate action to support the child's recovery. Early detection and intervention are essential for dealing with the impacts of child abuse and supporting the wellbeing of the child.

Moore (2023) emphasises that some abused children may try to conceal their experiences, therefore parents and other adults should create a safe and open environment where children feel comfortable sharing their concerns and, if necessary, obtaining professional assistance.

Sub-theme 2.2: Emotional support

IsiZulu-speaking caregivers may feel confused, furious and uncertain when a child discloses their experience of CSA (Van Duin, Verlinden, Tsang, Verhoeff, Brilleslijper-Kater, Voskes, Widdershoven & Lindauer, 2022). Instead, they should manage their emotional reactions and offer crucial emotional support to aid the child's healing process. This involves creating a safe environment, attentive listening, acknowledging their feelings, and helping to develop their self-confidence and self-worth. The study presents various participants' viewpoints on this subject:

I felt very confused, I did not know whether I should cry or get angry. When the child saw my reaction, she stopped talking. I wanted to confront the offender.

I will give my child a hug and hold them close when I see that they are depressed so that they feel I am with them in the whole process until they get help from a professional person.

I will hold my child's hand and encourage them to tell me everything that happened to them. If they do not want to talk, I will take them to a person of their choice so that they can talk about it.

When a child disclosed sexual abuse, the caregivers' reactions ranged from crying, rage, feeling helpless and refusing to acknowledge it. Some even stated that they wanted to confront the suspected criminal. Everstine and Everstine (2014) discovered that many caregivers are unprepared to respond appropriately to sexual abuse disclosures, which can have harmful consequences for the child. This could happen for a variety of reasons, including a lack of information about the signs of sexual abuse or being unprepared for such an event. Several respondents stated that their emotional response to the disclosure had a negative impact on the child, prompting the child to become unhappy and unwilling to continue the conversation. Fong, Bennett, Mondestin, Scribano, Mollen and Wood (2020) attest that children's readiness or otherwise to disclose abuse might be influenced by the caregivers' emotions or expectations. Caregivers' potential response, such as feelings of powerlessness and uncertainty about how to support the child, may influence whether the child discloses the abuse.

Furthermore, the findings show that caregivers must set aside their personal emotions and demonstrate fortitude to provide impartial and empathic emotional support to abused children. Emotional support for CSA survivors, according to Kaakinen, Coehlo and Steele (2018), can be empowering and encouraging, but also include setting limits. Such assistance can encourage children to talk openly about their experiences. Parental support is cited by Vaughan-Eden, LeBlanc and Dzumaga (2020) as a protective factor for these children. As required by the Children's Act No 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006), as amended, caregivers should encourage children to disclose abuse and provide emotional support throughout the disclosure process.

Sub-theme 2.3: Caregivers seeking professional support in disclosing CSA

Seeking professional support when suspecting a child has been sexually abused can be a critical move in reporting the abuse to the authorities and getting the child the help that they need. The following comments demonstrate this preference:

It is difficult to report to police and I do not feel comfortable as they ask a lot of questions making me feel like the suspect. I prefer disclosing the matter to the social workers working around Tsakane, they are always supportive.

I will approach a social worker in an empathetic environment, someone whom I trust will assist me without judging nor blaming me for the sexual abuse of my child.

The study indicates that some caregivers may have difficulties disclosing CSA to authorities, even if they have detected indicators of it. In such cases, caregivers commonly opt to confide in trusted social workers, who can aid them in reporting the abuse to the police. According to Faller and Everson (2014) and Goodyear-Brown (2012), caregivers frequently reveal CSA to a professional before reporting it to authorities. When a child discloses sexual abuse, caregivers frequently choose to seek professional assistance from doctors or local social workers for a variety of reasons. One could be that they lack the information or training needed to give adequate assistance and manage an intervention for the child. Another factor is that they may not want to deal with the situation alone or make judgments without consulting an expert in the field. They may also be anxious about the potential implications of mishandling the disclosure, such as retraumatising the child or risking any necessary legal action (Wallis & Woodworth, 2021).

Seeking assistance from professionals is critical in safeguarding and encouraging a sexually abused child's wellbeing. It provides caregivers with access to expert resources and information, assists in the management of emotional and psychological effects, and prevents additional harm. Caregivers should not be afraid to reach out for support if they suspect, or are aware of, the sexual abuse of a child.

Theme 3.3: Reasons for non-disclosure of CSA

Several factors have been identified as contributing to isiZulu-speaking caregivers' inability or reluctance to disclose CSA. The data revealed the following sub-themes, each with its own set of reasons contributing to non-disclosure: establishing physical proof, need for family intervention, psychological cost factors, and lack of trust in authorities.

Sub-theme 3.1: Physical evidence

Physical evidence is valuable in proving CSA complaints. Using tangible evidence can raise the likelihood of a successful conviction, deter perpetrators and provide justice to the victim. The following participant accounts bear this out.

Some caregivers don't have good relationships with the child and don't take time to listen to the child. In such cases the caregiver will only find out about the sexual abuse either through blood on child's clothes when washing them, or the child limping or failing to sit properly.

It was difficult to believe that the child I cared for accused my partner of being intimate with her, he treated her like a father. I only believed it when she was medically assessed that she was indeed raped.

It is easy to report to the police or the court when there is tangible physical evidence which makes it easy to link the perpetrator to the crime as CSA is difficult to prove in the absence of physical evidence.

Research participants indicated that, in the IsiZulu culture, there was a preference for disclosing cases of CSA only when concrete proof is available to confirm that the abuse occurred. Often abuse is discovered by chance when a child is referred to a doctor, social worker or psychologist because of behavioural or physical concerns. Genital injuries or scarring, difficulty walking or sitting, and sexually transmitted illnesses presenting in emergency rooms may suggest sexual abuse, which can be alarming for caregivers (Taylor, 2013).

Reitsema and Grietens (2016) noted that caregivers tend to intervene only if a child unintentionally confesses during a medical examination. Physical evidence is frequently seen as essential in court to prove abuse, as children may be hesitant to describe their experiences. However, Springer and Roberts (2017) express concerns that this reliance on physical evidence may result in some CSA cases being overlooked during investigations.

Cage (2022) argues that while physical evidence can support claims of abuse, it is not always necessary for successful prosecution, or for a child to receive proper therapy and support. Many CSA cases may lack physical evidence, especially when some forms of sexual abuse do not leave obvious physical injuries or biological evidence.

According to the Criminal Law (Sexual Crimes and Related Matters) Amendment Act 5 of 2015 (RSA, 2015), all cases of CSA must be reported as sexual crimes, even in the absence of physical proof. The veracity and consistency of the child's testimony become crucial in determining the legitimacy of abuse allegations. Corroborating evidence from witnesses or the child's behaviour can also be helpful in assessing the truth when tangible evidence is lacking.

Sub-theme 3.2: Family intervention

In the IsiZulu culture, child protection is viewed as the responsibility of the maternal family. When the perpetrator of CSA is a family member, it is more difficult to disclose the abuse, making caregivers hesitant to report it. Participants in this discussion expressed the following points of view:

The uncles had to be informed and give direction to the family when I disclosed to them that the girl I was caring for was sexually abused by our neighbour where we stayed.

It is difficult to report a family member to the police because it will be a double loss as I should deal with having a family member in prison plus the child may not be open enough to testify against a family member. I would rather advise her to stay away from him.

The study's findings emphasised the need of disclosing incidents of CSA within the family, particularly to older family members such as uncles, as a critical first step. This finding is consistent with prior research by Fontes and Plummer (2010), who linked it to isiZulu cultural societal norms and beliefs that favour family unity and intimacy. Theimer, Mii, Sonnen,

McCoy and Meidlinger (2020) highlight the bio-ecological model, which emphasises the need to take into account cultural environment and familial dynamics when developing interventions and treatments for CSA. The study's findings corroborate this strategy, as participants claimed that disclosure within the family was frequently the first informal response to CSA prior to any official involvement by the system.

When the perpetrator is a family member, it can be much more difficult to disclose sexual abuse. The isiZulu culture values family unity and avoiding the severe societal consequences of reporting a family member to authorities for CSA (Norman, 2016). Caregivers may be reluctant to speak up for fear of damaging the family's image, which can result in social ostracism and shame (Schomerus, Schindler, Rechenberg, Gfesser, Grabe, Liebergesell, Sander, Ulke & Speerforck, 2021). Furthermore, intra-family CSA frequently occurs in an environment of trust and familiarity, in which the offender may have developed authority and influence over the victim and the family. This dynamic complicates disclosure by evoking disbelief, denial or even guilt in the victim (Gekoski, Davidson & Horvath, 2016).

Regardless of cultural norms, isiZulu-speaking caregivers should prioritise the child's safety and wellbeing. The Criminal Amendment Act 5 of 2015 requires caregivers to report any CSA incidents to police, regardless of the family's conduct (RSA, 2015).

Sub-theme 3.3: Psychological cost factors

Disclosing instances of CSA has been found to have psychological costs. Disclosing abuse claims is critical, but it may be a difficult and unpleasant process for caregivers. Some of these costs are demonstrated by the examples supplied by participants.

The perpetrator may threaten to kill the child victim or the caregiver or any other significant family member of the victim. He said to the child he will report that they are in a relationship and that the child always undresses for him.

The neighbours and other community members labelled us liars after that, while the perpetrator told us that we will pay for getting him arrested.

I was not prepared to force the child to stand in court and talk, whilst she was not ready for it. I know what is happening in court, the child is tortured during cross-examination. How can I allow the child to go through this process and be retraumatised?

Experiences of CSA disclosure have significant psychological consequences, including the possibility of the child being removed from their care, negative labelling from neighbours and community members, manipulation by the perpetrator, caregiver trauma as a consequence of insensitive treatment from authorities, and re-traumatisation of the child during court cross-examination.

McElvaney, Lateef, Collin-Vézina, Alaggia and Simpson (2022) emphasise that exposing sexual abuse can be distressing for victims and caregivers because of the associated stigma. Caregivers fear judgment, disbelief and being held accountable, leading to feelings of shame and humiliation. They may also fear retaliation from the abuser, intensifying the trauma. Sexual abusers often target vulnerable children, making it difficult for them or their caregivers to report the abuse because of the abuser's control (Assink, van der Put, Meeuwsen, de Jong, Oort, Stams & Hoeve, 2019).

The stigma surrounding CSA disclosure can impact on the victim's family and society, fostering shame and denial around sexual abuse, discouraging victims from seeking treatment. Tashjian, Goldfarb, Goodman and Edelstein (2016) also suggest that caregivers may experience psychological consequences such as trauma and social stigma when abuse is disclosed.

Survivors of sexual abuse may find it distressing to disclose their experiences repeatedly. Caregivers may choose not to disclose the abuse to protect the child from further trauma during discussions or legal proceedings (Rapholo, 2014). However, not disclosing CSA can perpetuate abuse and put the child in a dangerous situation.

Sub-theme 3.4: Distrust of governmental authorities

The findings suggest that isiZulu-speaking people may be unwilling to report occurrences of CSA to government authorities because of a lack of trust. The following examples illustrate this point of view.

Reporting cases to police does not help. They ask many questions instead of just investigating the matter. The evidence will be there and instead of proceeding straight to arrest the alleged perpetrator, they make you feel like you have done something wrong by reporting.

The courts failed us, the alleged perpetrator was released on bail because the police said they can't keep him in prison because they were still busy with DNA and after everything, he will walk free. No, that is too much stress, for the child and me as the caregiver, I rather quit the whole process.

The overwhelming response was that both the police and the legal system fail both the child victim and the caregiver. As a result, participants expressed distrust in government authorities. This lack of trust is more pronounced in situations where the inquiry process is drawn out. There is a perception that the accusations are not being taken seriously by the authorities, or that no adequate investigation is being done.

Some victims and their families fear that the police are not doing enough to gather information, interview witnesses and follow up on leads. This leads to feelings of dissatisfaction and mistrust, especially if there are delays or errors in the inquiry process. Lindsay (2014) contends that a court system which is perceived to be inadequate can lead to a lack of trust in government authorities, because victims may believe they are not receiving appropriate legal support, attention or protection, and that the system is prejudiced against them. Theimer et al. (2020) added that victims who lack confidence in the government because of insufficient police support and a broken justice system may be reluctant to report sexual abuse cases or engage with the legal system. This could have serious consequences for victims, who may not get the support and justice they need to move past their experiences.

Sexual abuse victims' rights and wellbeing must be prioritised to build trust in authorities and the legal system. A transparent, unbiased and accountable justice system that gives victims a voice will empower victims and increase engagement with the court system. This will eventually motivate caregivers to report more cases of CSA.

Theme 4: Encouraging isiZulu caregivers to disclose CSA

All participants agreed that caregivers should be proactive in reporting CSA cases. Participants reviewed several approaches for encouraging caregivers to report CSA, such as community meetings and stakeholder awareness campaigns.

Sub-theme 4.1: Community meetings

Individuals and traditional leaders (izidunas) must collaborate to foster a culture of openness and support for the dilemma of dealing with CSA in the isiZulu community. We can help safeguard children from the devastating impacts of sexual abuse by working together to raise awareness and aid victims. Several participant accounts supported this viewpoint.

As a community we should organise imbizos allowing members of the community to engage with each other on issues affecting us here regarding the increase of CSA and how that can be stopped.

Caregivers should be able to approach the Izindunas who are able to call for a community meeting to raise awareness and encourage community members to have Ubuntu spirit and encourage them to report CSA.

Participants in the study emphasised the importance of community involvement in addressing CSA in isiZulu culture. They proposed organising imbizos, or community gatherings, to facilitate discussions about the problem and encourage reporting. Community gatherings, hosted by traditional leaders or Izindunas, can effectively address concerns like crime and CSA, promoting community cohesion and a sense of shared responsibility.

According to Goodyear-Brown (2012), a community's response to crime reflects its culture, and imbizos can assist to build a culture of reporting CSA to authorities, which is associated with the ubuntu concept, which promotes community and connection. This can reduce the stigma and shame that often prevent caregivers from reporting abuse claims (Baloyi & Lubinga, 2017).

Imbizos can cultivate a community culture that supports CSA reporting to authorities and empowers caregivers to come forward with abuse charges. These gatherings can foster harmony and a sense of shared responsibility, creating a more supportive environment for victims.

Sub-theme 4.2: Stakeholder awareness campaigns

Stakeholder awareness campaigns can help overcome barriers to disclosing cases of CSA in the isiZulu community, where cultural beliefs about sex as a sensitive matter, among other factors mentioned in the study, can impede or actively discourage disclosure. Individual accounts supplied by participants are indicated below.

There is an urgent need to dispel the myth of not talking about sex while also providing detailed information on the dynamics and different forms of CSA and the importance of reporting this.

The government through the MEC or the MMC for social development and other NGOs can organise awareness campaigns.

Campaigns to raise awareness about child sexual abuse should be directed not only towards caregivers but also towards young girls, as many may not recognise that they are being sexually abused by older men due to early exposure to drugs and alcohol and a desire for a fast-paced lifestyle.

Discussing sex is frequently considered inappropriate in the isiZulu culture. Khuzwayo-Magwaza (2021) confirms that in many African cultures sex is seen as a private matter, leading to discomfort in discussing sexual health and safety. Community awareness efforts are needed to change these views. Johnson (2019) noted a growing acknowledgment of the importance of open conversations about sex and sexuality.

Public awareness campaigns should inform people about various types of sexual abuse, its consequences for victims, and the importance of reporting such incidents. Mathews and Collin-Vézina (2016) support this approach, advocating for community-based programmes to increase the rate of CSA disclosure.

Rudolph, Zimmer-Gembeck and Hawkins (2018) suggest that awareness campaigns can also improve caregiver roles by promoting parental supervision, monitoring and involvement. In addition, they can boost children's self-efficacy, competence, wellbeing and self-esteem, thus reducing their vulnerability to abuse and enhancing their ability to respond appropriately.

Participants in the study stressed the need to educate minors and caregivers through community awareness programmes. Mathews and Collin-Vézina (2016) argue that educating both groups is essential for establishing a stronger social structure that protects children from CSA. Equipping children and caregivers with information and skills to recognise and report abuse can lead to more CSA disclosures and better child protection.

DISCUSSION

The study focused on isiZulu-speaking caregivers' opinions of CSA disclosure in the Tsakane community of Gauteng, South Africa. The findings are consistent with previous studies on CSA and caregiver perceptions undertaken by Marais (2022), Ramphabana et al. (2019), Rapholo (2014) and Zantsi (2014). The data confirm that CSA is a serious problem that affects children in the isiZulu community, yet it is typically underreported.

Understanding of CSA among isiZulu-speaking caregivers is critical in CSA prevention and disclosure (Mathews, Hendricks & Abrahams, 2016). However, the study did find that caregivers in the Tsakane Community had an insufficient understanding of the many forms of CSA, such as rape, statutory rape, child trafficking and child sexual exploitation.

Notably, caregivers can detect cases of CSA by noticing changes in the child's mood, behaviour, or physical health (Vaplon, 2015). Responding sensitively and supportively is vital to ensuring the child feels heard and trusted, which is critical for their healing process. Caregivers can also assist the child to receive proper support and care by monitoring their behaviour, providing emotional support and seeking expert assistance (Moore, 2023).

Several obstacles, including the need for physical evidence, concerns about family interference, psychological costs and a lack of faith in authorities, prevent isiZulu-speaking caregivers from reporting CSA. Tangible evidence is important in caregivers' decision to report abuse, and the absence of conclusive proof may raise concerns about the legitimacy of the child's disclosure, leading to delayed reporting (Fontes and Plummer, 2010; Reitsema & Grietens, 2016; Tashjian et al., 2016; Theimer et al., 2020). Furthermore, cultural norms such as family cohesion and loyalty can make it difficult to reveal intra-familial abuse. If caregivers disclose abuse, they may fear retraumatising the child or stigmatising the family. The study underscores the necessity of addressing the psychological wellbeing of both the child and the caregiver during the disclosure process. Caregivers' lack of trust in authorities shows their suspicion of the legal system and lack of confidence in its ability to respond correctly to abuse, which could be a result of previous unpleasant experiences or a lack of awareness about available resources and support services (Lindsay, 2014).

According to the findings of the study, community-based interventions such as imbizos and awareness campaigns can be extremely effective in persuading caregivers to disclose occurrences of CSA. Imbizos serve as discussion forums for a variety of community concerns, including CSA, whereas awareness campaigns help to raise awareness of CSA, its implications, preventative techniques, and accessible services for assistance and reporting (Goodyear-Brown, 2012). Community members can be educated about CSA by organising imbizos and awareness campaigns, which include knowledge on identifying signs of abuse, the importance of reporting suspected cases, and the availability of support services for survivors, all in accordance with the principles of ubuntu (Baloyi & Lubinga, 2017). Ubuntu emphasizes the connectivity of all people and the importance of children in isiZulu culture, hence harmful activities directed at children violate these values and must be addressed.

The study's findings are consistent with social cognitive theory, emphasising the dynamic interaction between caregivers and their surroundings (Bandura, 1986). Caregivers' perceptions and behaviours regarding CSA disclosure are influenced by their social context, including interactions with family, community members and societal norms. Furthermore, caregivers' actions may impact on the beliefs and behaviours of others in their social network.

IMPLICATION FOR PRACTICE

Social workers must be culturally sensitive and aware of the specific beliefs and values of isiZulu-speaking caregivers to engage with and assist them effectively.

It is critical to build trust with caregivers to communicate and disclose effectively. Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance will ensure safety when discussing delicate subjects like CSA.

Social workers should be aware of the obstacles to reporting CSA among isiZulu-speaking caregivers, such as fear of family interference, the need for actual evidence, and a lack of faith in authorities. Addressing these concerns requires empathy.

Collaboration with other professions, such as law enforcement and medical practitioners, will ensure a coordinated response to CSA situations, providing victims of CSA with additional support and safety.

Social workers must adopt a trauma-informed approach to guide sensitive and responsive interventions, acknowledging the impact of trauma on the child victim and their families. Providing victims and witnesses with safe and confidential reporting methods can encourage them to come forward.

CONCLUSION

The findings reveal that isiZulu-speaking caregivers in Tsakane are hesitant to report CSA incidents. Some families may lack understanding of CSA as mandated by South African legislation. African values, environmental issues and psychological cost factors contribute to this reluctance. Paternalistic traditions, sex as a forbidden subject, the dependence on tangible proof, the emphasis on the family's reputation and status within the community, the perpetrator's role within the family, keeping family matters private, and resolving conflicts internally all contribute to this problem. Additionally, the fear of retaliation, lack of trust in authorities, and enduring trauma caused by repeatedly recalling such experiences are major obstacles preventing the disclosure of CSA within the isiZulu community.

Addressing these challenges requires culturally appropriate, community-led solutions such as imbizos and educational awareness campaigns based on ubuntu principles to promote communalism, compassion and connectivity among individuals and communities. This may encourage survivors and caregivers to break down cultural barriers hindering CSA disclosure. Future research can focus on interventions specific to the isiZulu community, improving child safety, survivor care and preserving their cultural context.

REFERENCES

Alaggia, R. Collin-Vézina, D. & Lateef, R. 2019. Facilitators and barriers to child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures: A research update (2000-2016). Trauma Violence Abuse, 20(2): 260-283. https://doi:10.1177/1524838017697312. [ Links ]

Amoah, P. A., Gyasi, R. M. & Halsall, J. 2016. Social institutions and same-sex sexuality: Attitudes, perceptions and prospective rights and freedoms for non-heterosexuals. [Online] Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/23311886.2016.1198219?needAccess=true [Accessed: 25/01/2021]. [ Links ]

Artz, L., Ward, C. L., Leoschut, L., Kassenjee, R. & Burton, P. 2018. The prevalence of CSA in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 108(10): 791-792. https://doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i10.13533. [ Links ]

Assink, M., van der Put, C.E., Meeuwsen, M.W.C.M., de Jong, N.M., Oort, F.J., Stams, G.J.J.M. & Hoeve, M. 2019. Risk factors for child sexual abuse victimization: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5): 459-489. https://doi:10.1037/bul0000188. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. 2016. The practice of social research. 14th ed. Boston: Cengage. [ Links ]

Baloyi, M.L. & Lubinga, E.N. 2017. After Izimbizo, what next? A participatory development communication approach to analysing feedback by the Limpopo Provincial Government to its citizens. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 13(1): a402. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v13i1.402. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc. [ Links ]

Budoo, A. & Ramnauth, D. 2018. A report on child marriage in Africa. Centre for Human Rights, African Commission on Human and People's Rights and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women in Africa. [Online] Available: https://www.chr.up.ac.za/images/pubications/centrepublications/documents/child_marriage_report.pdf [Accessed: 19/03/2020]. [ Links ]

Cage, E.C. 2022. The science of proof: Forensic medicine in modern France. Cambridge. Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Cele, B. 2022. Safety of Ekuruhleni residents under siege as murder sexual offences and hijackings increases. [Online] Available: https://content.voteda.org/gauteng/tag/crime/ [Accessed: 04/04/2023]. [ Links ]

Clark, J. 2015. Why is sexual violence so endemic in South Africa and why has it been so hard to combat? [Online] Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/why-sexual-violence-so-endemic-south-africa-and-why-has-it-been-so-hard-combat-jessica [Accessed: 20/02/2019]. [ Links ]

Colgan, D. 2009. The Children's Act explained. Booklet 1: Children and parents - Rights and responsibilities. [Online] Available: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/1276/file/ZAF-childrens-act-explained-booklet-1-2009.pdf [Accessed: 29/08/2021]. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

De Villiers, A. 2014. Child Rights: Key international treaties in the promotion, protection and fulfilment of children's rights. UNICEF. [Online] Available: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/1526/file/ZAF-child-rights-key-international-treaties.pdf [Accessed: 10/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Efevbera, Y. & Bhabha, J. 2020. Defining and deconstructing girl child marriage and applications to global public health. [Online] Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/23311886.2016.1198219?needAccess=true [Accessed: 14/04/2021]. [ Links ]

Everstine, D.S. & Everstine, L. 2014. Sexual trauma in children and adolescents. Dynamics & treatment. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Faller, K.C. & Everson, M.D. 2014. Contested issues in the evaluation of CSA. A response to questions raised in Kuehnle and Connell's Edited Collection. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fong, H., Bennett, C. E., Mondestin, V., Scribano, P., Mollen, C. & Wood, J. N. 2020. The impact of CSA discovery on caregivers and families: A qualitative study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35: 21-22. https://doi:10.1177/0886260517714437. [ Links ]

Fontes, L. A. & Plummer, C. 2010. Cultural and disclosure issues: Cultural issues in disclosure of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19: 491-518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2010.512520. [ Links ]

Fortinash, K. M. & Holoday Worret, P. A. 2014. Psychiatric Mental health nursing. St Louis: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Gcwabe, L. & Gwala, N. 2021. Rape, childhood sexual abuse continues to plague SA. [Online] Available: https://health-e.org.za/2021/12/09/rape-childhood-sexual-abuse-continues-to-plague-sa/ [Accessed: 10/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Gekoski, A., Davidson, J. C. & Horvath, M. A. H. 2016. The prevalence, nature, and impact of intrafamilial child sexual abuse: Findings from a rapid evidence assessment. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 2(4): 231-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-05-2016-0008. [ Links ]

Goodyear-Brown, P. 2012. Handbook of child sexual abuse: Identification, assessment and treatment. New York: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Gorman, L. M. & Anwar, R. F. 2019. Mental health nursing. 5th ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. [ Links ]

Haskell, L. & Randall, M. 2019. The impact of trauma on adult sexual assault victims. [Online] Available: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2019/jus/J4-92-2019-eng.pdf [Accessed: 08/10/2021]. [ Links ]

Hendricks, M. 2014. Mandatory reporting of child abuse in South Africa: Legislation explored. South African Medical Journal, 104(8): 550 552. https://doi:10.7196/SAMJ.8110. [ Links ]

Horowitz, J., Parker, K., Graf, N. & Livingstone, G. 2017. Americans widely support paid family and medical leave but differ over specific policies. Personal experiences with leave vary sharply by income. [Online] Available: file:///C:/Users/23509066/Downloads/Paid-Leave-Report-FINAL_updated-10.2.pdf [Accessed: 23/07/2022]. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. 2019. S.O.G. I. E Handbook. Sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression. affirming approach and expansive practices. New York: HRI. [ Links ]

Kaakinen, J. R., Coehlo, D. P. & Steele, R. 2018. Family health care nursing. Theory, practice, and research. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. [Online] Available: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/trauma/trauma_Jeng.pdf [Accessed: 13/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Karimakwenda, N. 2013. "Today it would be called rape": A historical and contextual examination of forced marriage and violence in the Eastern Cape. In: Claasens, A & Smythe, D. (eds). Marriage land & custom. Essays on law and social change in South Africa. Claremont: Juta and Co. [ Links ]

Khuzwayo-Magwaza, L. P. 2021. The "Closet" and "Out of the Closet" versus "Private Space" and "Public Space": Indigenous knowledge system as the key to understanding same-sex sexualities in rural communities. Religions, 12(9): 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090711. [ Links ]

Kim, J. E., Cho, Y. R., Choi, B. E., Lee, S. H. & Lee, T. H. 2017. Two cases of hymenal scars occurred by child rape. Obstetrics and Gynaecology Science, 60(6): 612-615. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2017.60.6.612. [ Links ]

Lindsay, M. 2014. A Survey of survivors of sexual violence in three Canadian Cities. [Online] Available: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rr13_19/rr13_19.pdf [Accessed: 19/03/2019]. [ Links ]

Marais, E. 2022. Understanding the perceptions of IsiXhosa-speaking caregivers on disclosing child sexual abuse in the Western Cape. Master's thesis. North-West University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Mathews, B. & Collin-Vézina, D. 2016. CSA: Raising awareness and empathy is essential to promote new public health responses. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37: 304-314. https://doi:10.1057/jphp.2016.21. [ Links ]

Mathews, S., Hendricks, N. & Abrahams, N. 2016. A psychosocial understanding of child sexual abuse disclosure among female children in South Africa. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 25(6): 636-654. https://doi:10.1080/10538712.2016.1199078. [ Links ]

McElvaney, R., Lateef, R., Collin-Vézina, D., Alaggia, R. & Simpson, M. 2022. Bringing shame out of the shadows: Identifying shame in child sexual abuse disclosure processes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37: 19-20. https://doi:10.1177/08862605211037435. [ Links ]

Meinck, F., Cluver, L. D., Boyes, M. E. & Loening-Voysey, H. 2016. Physical, emotional and sexual adolescent abuse victimisation in South Africa: Prevalence, incidence, perpetrators and locations. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(9): 910-916. https://doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205860. [ Links ]

Moore, W. 2023. Signs of child abuse. [Online] Available: https://www.webmd.com/children/child-abuse-signs [Accessed: 30/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Msuya, N. H. 2017 Tradition and culture in Africa: Practices that facilitate trafficking of women and children. Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence, 2(1): 1-36. https://doi.org/10.23860/dignity.2017.02.01.03. [ Links ]

Norman, K. 2016. Into the Laager: Afrikaners living on the edge. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Odhayani, A. A., Watson, W. J. & Watson, L. 2013. Behavioural consequences of child abuse. Canadian Family Physician, 59(8): 831-836. [ Links ]

Pijoos, L. 2017. Sexual assault claims at primary school: Lesufi slams. News 24, 23 November 2017.. [Online] Available: https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/sexual-assault-claims-at-primary-school-lesufi-slams-principal-20171123 [Accessed: 07/08/2020]. [ Links ]

Pipe, M., Lamb, M. E. & Orbach, Y. 2013. CSA. Disclosure, delay, and denial. New York: Taylor and Francis. [ Links ]

Ramphabana, L. B., Rapholo, S. F. & Makhubele, J. C. 2019. The influence of familial factors towards the disclosure of child sexual abuse amongst Vhavenda Tribe. African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 18(2): 173-188. [ Links ]

Rantao, M. & Tshabalala, T. 2022. The alarming rise in the scourge of child trafficking in SA. [Online] Available: https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/news/the-alarming-rise-in-the-scourge-of-child-trafficking-in-sa-c5e47dd4-12e1-4f40-8196-235e2924c11e [Accessed: 14/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Rapholo, S. F. 2014. Perceptions of Pedi-speaking caregivers regarding the disclosure of CSA. Master's thesis. North-West University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Reitsema, A. M. & Grietens, H. 2016. Is anybody listening? The literature on the dialogical process of CSA disclosure reviewed. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 17(3): 330-340. https://doi:10.1177/1524838015584368. [ Links ]

Rendle, K. A., Abramson, C.M., Garrett, S. B., Halley, M. C. & Dohan, D. 2019. Beyond exploratory: A tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. [Online] Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6720470/ [Accessed: 29/09/2020]. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2006. Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005 as amended. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944. 19 June 2006. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2013. Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act No 7 of 2013. Government Gazette, Vol. 577, No. 544. 29 July 2013. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2015. Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Act, No. 32 of 2007 as amended. Government Gazette, Vol. 601, No. 593. 7 July 2015. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M. & Ormstrong, R. 2014. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Rudolph, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, J. & Hawkins, R. 2018. Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk. Child Maltreatment, 23(1): 96-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517729479. [ Links ]

Sadiki, R. 2022. Statutory rape: An underestimated gender-based violence issue. [Online] Available: https://health-e.org.za/2022/05/19/statutory-rape-an-underestimated-gender-based-violence-issue/ [Accessed: 13/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Schomerus, G., Schindler, S., Rechenberg, T., Gfesser, T., Grabe, H. J., Liebergesell, M., Sander, C., Ulke, C. & Speerforck, S. 2021. Stigma as a barrier to addressing childhood trauma in conversation with trauma survivors: A study in the general population. [Online] Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0258782 [Accessed: 30/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Springer, D. W. & Roberts, A. R. 2017. Social work in juvenile and criminal justice systems. 4th ed. Illinois: Charles C Thomas Publisher. [ Links ]

South African Police Service. 2019/2020. Crime situation in RSA Twelve months 01 April 2021 - 31 March 2022. [Online] Available: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/april_to_march_2019_20_presentation.pdf [Accessed: 13/04/2021]. [ Links ]

South African Police Service. 2021/2022. Crime situation in RSA Twelve months 01 April 2021 - 31 March 2022. [Online] Available: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/long_version_presentation_april_to_march_2021_2022.pdf [Accessed: 20/06/2022]. [ Links ]

Tashjian, S. M., Goldfarb, D., Goodman, J. A. Q. & Edelstein, R. 2016. Delay in disclosure of non-parental CSA in the context of emotional and physical maltreatment: A pilot study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 58(1): 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/jxhiabu.2016.06.020. [ Links ]

Taylor, R. B. 2013. Family medicine principles and practice. 4th ed. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Tesch, R. 1992. Qualitative research: Analysis types and software tools. New York: Falmer. [ Links ]

Theimer, K., Mii, A. E., Sonnen, E., McCoy, K. & Meidlinger, K. 2020. Identifying and addressing barriers to treatment for CSA survivors and their non-offending caregivers abuse survivors and their non-offending caregivers. [Online] Available: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/323867358.pdf [Accessed: 07/02/2021]. [ Links ]

Van Aswegen, B. 2022. The alarming rise in the scourge of child trafficking in SA. [Online] Available: https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/news/the-alarming-rise-in-the-scourge-of-child-trafficking-in-sa-c5e47dd4-12e1-4f40-8196-235e2924c11e [Accessed: 14/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Van Duin, E. M., Verlinden, E., Tsang, V. M. W., Verhoeff, A. P., Brilleslijper-Kater, S. N., Voskes, Y., Widdershoven, G. A. M. & Lindauer, R. J. L. 2022. A sexual abuse case series of infants and toddlers by a professional caregiver: A qualitative analysis of parents' experiences during the initial crisis period post-discovery. Child Abuse & Neglect, 125: 105460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105460. [ Links ]

Vaplon, C. S. 2015. The effects of parental response on their children's trauma experience. [Online] Available: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/530 [Accessed: 10/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Vaughan-Eden, V., LeBlanc, S. S. & Dzumaga, Y. 2020. Succeeding with non offending caregivers of sexually abused children. [Online] Available: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-62122-7_15-1 [Accessed 10/03/2023]. [ Links ]

Wallis, C. R. D. & Woodworth, M. 2021. Non-offending caregiver support in cases of CSA: An examination of the impact of support on formal disclosures. [Online] Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S01452134210000287via%3Dihub [Accessed: 24/03/2022]. [ Links ]

Wrigley-Asante, C., Owusu, G., Otneng-Ababio, M. & Owusu, A. Y. 2016. Poverty and crime: Uncovering the hidden face of sexual crimes in urban low-income communities in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography, 8(1): 32-50. [ Links ]

Xaba, N. 2021. Intergenerational relationships: Experiences of grandmothers in caring for their grandchildren in an urban area in KwaZulu-Natal. Durban. Master's thesis. University of Kwazulu Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Yearwood, E., Pearson, G. S. & Newland, J. A. 2012. Child and adolescent behaviour health.: A resource for advanced practice psychiatric and primary care practitioners in nursing. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Zantsi, N. T. 2014. Beliefs and knowledge of isiXhosa speaking people about child sexual abuse in a rural area. Master's thesis. North-West University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Article received: 16/8/2022

Article accepted: 18/08/2023

Article published: 26/03/2024

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Douglas Mavhunga was a MA (Forensic Practice) student, affiliated with the research entity COMPRES, within the Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Psychosocial Health, Subject group Social Work at the North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa, and is currently employed by the Department of Social Development in Gauteng. The article resulted from his master's degree, conducted from January 2017 to December 2020, and he wrote the initial draft of the article.

Pieter Boshoff is a Senior Lecturer affiliated with the research entity COMPRES, within the Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Psychosocial Health, Subject Group Social Work at the North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa. His field of specialisation include trauma intervention, qualitative and quantitative research methodology, and the integration of trauma-informed practices within social work education. He supervised the study from January 2017 to November 2020 and assisted with the writing of the draft article and final editing.