Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.60 n.1 Stellenbosch 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/60-1-1255

ARTICLES

Infidelity amongst young married couples: suggestions for social work intervention

Manare Belsie NgwashengI; Rembuluwani Paul MbedziII

IUniversity of South Africa, Department of Social Work, Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2361-8992 belsie.ngwash@gmail.com

IIUniversity of South Africa, Department of Social Work, Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0805-9958 mbedzrp@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Infidelity is a common phenomenon in modern society and a major factor in marital dissolution across the globe. A qualitative research approach was used in this study to develop an in-depth understanding of the experiences and impact of infidelity amongst young married couples. The participants were purposively selected from a population of young married couples who had experienced infidelity in their marriage and lived within the municipal borders of Lepelle-Nkumpi, in Limpopo province, using the snowball technique. Tesch's eight steps were used to analyse the data. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, the researchers assessed the qualitative data for credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability. The findings highlight that young married couples experiencing marital infidelity require direction from social workers to understand the process of recovery from any type of infidelity to bring about improvement and change in their marriage.

Keywords: infidelity experiences; infidelity; social work; social work interventions; young married couples

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Infidelity has become a common phenomenon in modern society (Jahan et al., 2017) and a major factor in marital dissolution across the globe (Fincham & May, 2017). Bahareh (2011) confirms that infidelity is the most significant contributing factor in divorce. According to Pace (2020), infidelity in a marriage means different things for different people. This is supported by Rada (2012), who postulated that two individuals involved in the same relationship may have different definitions of what constitutes infidelity or an extramarital adventure, which makes defining this phenomenon a remarkably complex task. Hence, the meanings ascribed to the term 'infidelity' as applied by researchers in one study may be different from the meanings ascribed by other researchers in their studies. Despite the prevalence of infidelity amongst young married couples and its implications on their marriages, the researchers discovered that there is still a knowledge gap, because previous studies did not focus specifically on infidelity amongst young married couples. Previous studies conducted in South Africa focused on the factors contributing to divorce among young couples in Lebowakgomo (Mohlatlotle, Sithole & Shirindi, 2018); exploring cheating behaviour amongst married men and women in a South African university (Idemudia & Mulaudzi, 2019); risky sexual behaviour among married and cohabitating women and its implications for sexually transmitted infections in Mahikeng, South Africa (Godswill & Natal, 2016); long-term concurrent partnerships, pregnancy and HIV risk dynamics among South African young adults (Harrison & O'Sullivan, 2010); and exploring extramarital sexual relationships as a precursor to psychosocial problems: a concern for social work practice (Masilo, 2019). It is evident that nothing has been documented to date which addresses the challenge of infidelity amongst young married couples or the adverse consequences that young married couples suffer when infidelity has been committed. Infidelity among young married couples is a significant area of concern; by understanding its complexity, social workers can assist couples to navigate the difficulties of infidelity and work towards restoring and maintaining healthy, fulfilling relationships by conducting further research, providing counselling and support services, and advocating for comprehensive education programmes for sustaining relationships.

In this article the researchers discuss the forms and causes of infidelity, the consequences of extra-marital activities, the role of the social workers, the theoretical framework that was used for the study, the research methodology, research findings and conclusions, and the implications for social work.

FORMS AND CAUSES OF INFIDELITY

Infidelity destroys many marriages and relationships regardless of culture, gender, age and nationality (Leeker & Carlozzi, 2014; Sharpe, Walters & Goren, 2013). The study conducted by Gemmer (2012) revealed that approximately 20-40% of men and 20-25% of women involve themselves in a minimum of one extramarital affair in their lives. According to Milhausen, Janssen and Mark (2011), it has been projected that between 25-50% of divorcees conveyed spousal infidelity as the key cause of divorce in Western countries. Bahareh (2011) pointed out that, based on research reports, 90% of all divorces have their roots in infidelity.

Similarly, Idemudia and Mulaudzi (2019) postulate that cheating behaviour among married persons is the main concern that affects most marriages, with its dreadful effects accounting for over 90% of divorces in South Africa. Mohlatlotle et al. (2018) indicated that a limited number of marriages among young couples between the ages of 18 and 35 in South Africa last beyond five years, because divorce has become an accepted alternative to resolving their marital problems. In South Africa men can have several sexual partners before marriage as proof of their strong sex drive and manliness (Ngazimbi, 2009). In certain South African cultures, it appears that extra-marital sexual relations are commonly acceptable in societal practice (Masilo, 2019). South African culture also has normalised polygamy, while Matshidze and Nemutandani (2017) noted that having an extra-marital relationship is not something an African wife is likely to contest. In another South African study, both men and women reported being driven to engage in multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships whilst married (Ruark et al., 2014).

Young married couples are faced with different forms of infidelity, such as physical, emotional, opportunistic, romantic and commemorative infidelity. Idemudia and Mulaudzi (2019) also indicate that types of cheating behaviours include, amongst others, emotional and sexual infidelity. In the former a married individual develops a deep emotional bond with someone other than their partner and cheats on their partner. In the latter, the married partner engages in sexual intercourse with someone other than their partner. One of the most recognised or experienced forms of infidelity among young married couples is physical infidelity. These types of infidelity may differ in meaning, levels of emotional pain caused, and consequences for each couple (Leeker & Carlozzi, 2014), and often differ in nature from person to person (Pour, Ismail, Jafaar & Yusop, 2019).

There are several root causes and factors that lead to marital infidelity. These include personal, relational and contextual factors. Infidelity is typically sexual in nature, but that does not mean that its motivation is fundamentally sexual. Infidelity is usually motivated by several complex factors (Spitzberg, 2016). Fincham and May (2017) note that individual, relationship and contextual factors have received regular attention in attempts to predict infidelity. Understanding the factors that influence people's involvement in extra-marital affairs is relevant to developing interventions that reduce the prevalence of infidelity, which in turn increases the rate of marital satisfaction and decreases the rate of divorce.

There are many reasons related to a married person becoming involved in an extramarital affair (Ojedokun, 2015). Tsapelas, Fisher and Aron (2010) indicate that people who engage in infidelity are mostly "open to new experiences", more unreserved than their partners and easily prone to "boredom". Up to a quarter of persons who have engaged in unfaithfulness cite "revenge" or attempting to restore a relational balance as causes of their infidelity. Their affairs function as a deliberate communicative act (Spitzberg, 2016). Revenge hostility refers to infidelity that is committed to punish a marital partner for the partner's perceived wrongdoings. A study in South Africa found that generally men have more power in marital sexual matters than women (Godswill & Natal 2016). Strong sexual desire and sexual dissatisfaction in the marital relationship are common reasons for married persons to pursue extra-marital relationships (Project Search, 2011).

The literature cites several contextual factors that contribute to infidelity. Bhattarai (2012) reported an upsurge in extra-marital affairs in Nepal that were attributed to economic factors such as far-off employment when spouses migrated to other parts of the country or outside their country of origin to secure employment. Certain work environments create increased interactional opportunities amongst employees which in some instances lead to employees engaging in extra-marital relationships (Carter, 2014). Ojedokun (2015) confirmed that in some instances couples enter an extramarital affairs as a result of poverty. Schonian (2013) found that the physical impact of infidelity can also develop into long-term extra-marital affairs.

Extra-marital affairs, according to Stinley (2017), can have several negative consequences in different areas of a couple's relationship, such as their physical, emotional, relational and economic lives, which may place the participant and their affected spouse at risk of trauma, sexually transmitted diseases, shock, anger, self-doubt and depression. Those affected by infidelity may experience psychological symptoms, such as depression and anxiety which may contribute to the development of serious health problems (Schonian, 2013). These negative consequences affect both partners and their children (Pour et al., 2019). Infidelity not only affects the married couples, but also their immediate families, and even the following generation, as well as society at large. The immediate relationships between family members are strained by infidelity, leading to dysfunctional family dynamics with potential long-term consequences. Moreover, children who observe or learn of infidelity in their parents' marriage may suffer psychological and emotional effects, and infidelity can reinforce unfavourable notions or misconceptions about fidelity in marriage, which may in turn negatively influence social and cultural norms (Negash & Morgan, 2016).

SOCIAL WORK INTERVENTIONS

Given the adverse consequences of infidelity and its impact on marriages, the individuals who have been cheated on find themselves needing some form of support to enable them to cope. It is worth noting that there are several avenues that they may pursue, which include individual counselling, support groups, and seeking support from friends and family (Pace, 2020). Developing a preventative intervention may ultimately help married couples avoid the damaging and traumatic experience of infidelity (Fye & Mims, 2019). Through preventative intervention, social workers can empower couples with the knowledge, skills and resources to proactively protect their relationships by fostering strong resilient marital bonds that protect their relationships from the risks of infidelity. Leeker and Carlozzi (2014) stress the importance of therapists such as social workers fully conceptualising the impact that infidelity has on their clients, providing them with the knowledge and skills to empower them to process and cope with infidelity. When dealing with issues around infidelity, social workers assist not only young married couples, but everyone around them who is affected (Negash & Morgan, 2016). This approach is supported by Miley, O'Meila and Dubois (2009), who noted that social work intervention strategies provided by social workers need to target different systems at different levels of the eco-system. Social workers must work directly with clients, their families and communities. These levels of interventions can be understood in relation to the different methods of social work intervention, namely casework (one-on-one sessions), group work (support groups), community work (awareness campaigns on issues surrounding infidelity), research and administration. Social workers must equip young married couples who experience infidelity with problem-solving skills and coping strategies and link them to relevant resources.

Anastas (2014) stated that social work has three dimensions, aims or functions; (i) the therapeutic, which may promote change or offer support; (ii) problem-solving in human relationships, which promotes the interpersonal and social "harmony" or serves as a social control function; and (iii) to promote social development and/or social change. This is supported by Marin, Christensen and Atkins (2014), who postulated that the interventions provided by social workers seek to improve couples' distressed relationships or their move towards separation. The purpose of couples' counselling is to enable both partners to develop to their full potential, enrich their lives and prevent dysfunction, as stated by Rautenbach and Chiba (2010). Therefore, enhancing access to a well-informed and coherently developed psycho-educational intervention strategy that incorporates interactive activities that address infidelity, and facilitated by an experienced/seasoned social services practitioner on a conveniently regular basis, may serve as an essential protective factor for young married couples confronting infidelity.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The researchers incorporated resilience and strength-based theory into this study. According to Van Breda (2018), resilience focuses on what "adversity" and "outcomes" mean, the possibility of being resilient, and how resilience processes operate. Positive factors that promote resilience, as identified by Baloyi (2011), include: the ability to cope with stress effectively and healthily; seek help from professional counsellors; believe that there is something good one can do to manage one's feelings; seek social support and connections with others such as family or friends; self-disclosure of the trauma to loved ones; cultivate an identity as a survivor; develop the capacity for learning; and bolster a positive innovative vision.

In other words, the young married couple can collaborate to find solutions to overcome the challenges in their relationship that contributed to the infidelity, or address the negative consequences of the infidelity by using methods which include: joint decision-making; clarifying their expectations and needs in terms of how infidelity can best be avoided in the future; giving open expression to their positive and painful feelings; and providing one another with information about how issues of infidelity have affected them personally. Even in the aftermath of infidelity, young married couples can be resilient and make their marriage work. Resilience in the context of this study would mean that individuals affected by infidelity can shift their focus onto the positive and away from the negative by making a deliberate effort to look for the positive aspects emerging from the experiences of the infidelity, enjoying their marriage and nourishing the positive experiences, being able to build on positive feedback rather than allowing themselves to be broken down by what is happening or has happened in their relationship (Van Dijk, 2020).

Infidelity is a complex phenomenon that is unique to individuals in their particular situation, which may lead them to focus on the weaknesses with their relationships. Gottlieb's (2013) strengths-based theory posits that people must be viewed holistically, and the focus should be on their individual strengths, what works and functions properly in their relationships, how individual partners complement one another's characteristics, and what resources they can draw on to assist them to deal fruitfully with their lives. People develop strengths not despite their trials and adverse experiences, but because of them (Myers-Walls, 2017). This implies that focusing on strengths does not mean overlooking challenges or turning struggles into strengths (Pattoni, 2012). The shift from a deficit to a strengths perspective highlights the strengths, skills and abilities that people have (Pulla & Francis, 2015). This is to say, regardless of infidelity, couples have strengths and the personal capacity to change and grow and the resources to resolve their problems. These factors constitute resilience. Problems such as infidelity can blind people to noticing their strengths, hence the strengths-based theory promotes bouncing back from adversity rather than dealing with deficits. People's ability to bounce back in the aftermath of infidelity depends mostly on their ability to forgive.

Both theories were integrated into the findings and conclusions on the experiences and impact of infidelity on young married couples, and both their implied recommendations for seeking social work support services were presented.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The aim of the study was to develop an in-depth understanding of the experiences and impact of infidelity amongst young married couples.

To achieve the aim of this study, the following research objectives were posited:

• To explore and describe the experiences of infidelity amongst young married couples;

• To explore and describe the impact of infidelity on young married couples;

• To explore and describe the suggestions made by young people who have experienced infidelity in their marriages regarding social work support services.

The researchers followed a qualitative research approach and applied explorative, descriptive, contextual and phenomenological research designs for this study (Creswell, 2014). The population of the study consisted of young married couples, aged between 18-35 years, who had been married for less than 5 years and had experienced infidelity in their marriage and who lived within the municipal borders of Lepelle-Nkumpi, in Limpopo Province. A sample of 10 participants was drawn using purposive and snowball sampling. The researchers also took into account recommendations and referrals from social work practitioners employed at the Department of Social Development as well as from participants who knew other young married couples who had been married for five years or less and experienced infidelity in their marriage.

The data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews using open-ended research questions. It is worth noting that two participants were identified to participate in a pilot test before the execution of the main research study in order to test the research tool. The researchers utilised the eight steps for analysing data by Tesch (1990). To ensure the final trustworthiness of qualitative data, the researchers applied credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability criteria as the characteristics of the model by Lincoln and Guba (1985). The Research and Ethics Committee of Unisa's Department of Social Work granted ethical clearance for this research project and the researchers ensured adherence to the ethical considerations for research by obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, protecting participants' anonymity, carefully managing research information, securing the protection of all participants, and ensuring that debriefing was available for all participants who needed it.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

This section presents the findings. The demographic data of the research participants, as well as an overview of the themes, subthemes and categories that emerged from the interviews conducted with the young married couples will be presented and supported with direct quotes or storylines taken from the transcripts of the interviews.

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA OF THE RESEARCH PARTICIPANTS

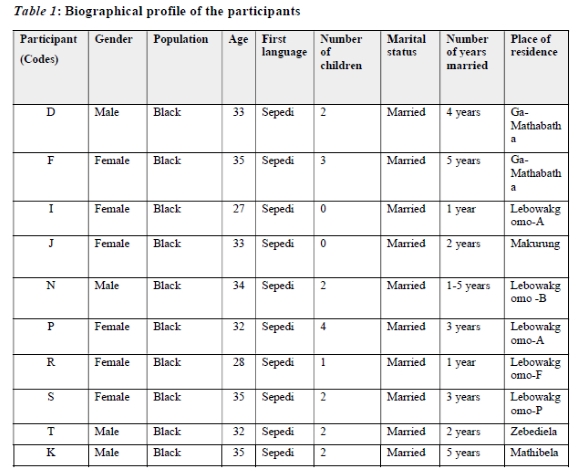

Table 1 presents the demographic particulars of the spouses who participated in this study, using individual codes for each participant. The demographic details are important because they offer information about the participants' backgrounds and personal experiences as affected by their contexts and personal perspectives, which may have some bearing on their responses to the research questions.

Table 1 reflects the demographic particulars of the participants as categorised in terms of participants' codes, gender, population, age, first language, number of children, marital status, number of years married and place of residence. Four males and six females participated in the study. All participants were black and spoke Sepedi as their first language. Their ages ranged from 27-35 years of age. All participants were married at the time of the study and have been married for periods between one and five years. All the participants were residents in Lepelle-Nkumpi municipality in Limpopo.

OVERVIEW OF THE THEMES AND SUB-THEMES

Both the researchers and the independent coder identified several themes in the process of data analysis. The six themes and sub-themes that emerged from the information provided by young married couples who had experienced infidelity in their marriage are outlined below.

Theme 1: Spouses' explanations of the reasons for the marital infidelity

The participating spouses were asked to describe the reasons for the infidelity in their relationship. The subthemes that emerged were as follows: was living elsewhere, being bored and tempted, under the influence of alcohol, feeling unappreciated or unhappy; peer pressure, technology, to spite or wreak revenge on the spouse who had cheated.

Living elsewhere was one of the reasons for the participating spouse's infidelity.

... and because of employment as well. Because I have moved from where I am ...my place of domicile to a workplace. So, ever since I came to a new environment, I started... cheating on my partner. (Participant D)

Kioko (2015) stated that time spent away from home for work normally encourages extramarital affairs as a result of the loneliness and fantasies which force married couples to seek sexual fulfilment outside of marriage.

One participating spouse stipulated that boredom was one of the reasons behind their infidelity.

... my reasons for infidelity were that... I've moved for a year, and I was working in Rustenburg for a year... and I was away from home... So, being in a foreign province, away from home.feeling the boredom you know.I think at some point I was open to a new experience... To be honest I was getting too much attention... (Participant K)

Many people start cheating when they are fed up or bored with each other's company (Jesse, 2021). Watson (2019) posits that boredom is a major cause of infidelity among married couples; when spouses live together for a while, they tend to get used to one another, the excitement disappears, and their relationship becomes boring. In response to this, one or both spouses may end up searching for an exciting relationship outside their marriage, which consequently leads to unfaithfulness.

A participating spouse stipulated that alcohol influenced him to commit adultery.

My reason for cheating was... mostly derived from alcohol. (Participant T)

Project Search (2011) shows that alcohol use can lower inhibitions and provide opportunities for people to meet potential sex partners. In addition, problematic drinking, alcohol dependence and illicit drug use are related to infidelity (Fincham & May, 2017).

One participating spouse indicated that they engaged in infidelity because they were feeling unappreciated by their spouse.

...I was feeling unappreciated by my spouse... because we were both working but...I often had to carry the burden of housework.and childcare.I had to do everything by myself. even on days where I get home from work tired. (Participant F)

Most of the individuals who commit infidelity state they are ignored, unrecognised, unloved, or feel insecure or unappreciated by their spouses, which then translates into cheating as they search for what they lack in their marriage (Watson, 2019). The inability of spouses to handle marriage issues could progress into potentially serious problems such as seeking attention from co-workers or close friends, which could result in the likelihood of unfaithfulness.

Peer pressure was described by one participating spouse as the reason behind their infidelity. Carter (2014) indicated that men's friendships with other males may play an important role in shaping and reinforcing social norms about multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships inside and outside of marriage. One of the contributing factors associated with infidelity, according to Spitzberg (2016), is peer pressure.

I think peer pressure... And another thing is that we got married at a young age. (Participant P)

One participating spouse stipulated that technology (social media) contributed to their infidelity.

I think also technology contributed to our infidelity... they flirt over the phone with girls...social media... WhatsApp, Facebook... (Participant S)

McDaniel and Coyne (2016) stated that social media promotes behaviours that may be potentially harmful to romantic relationships, such as communicating with alternative partners, which may create relationship conflicts and even breakups or divorce. Technology usage generally can interfere with relationships between married couples, potentially causing conflict and lower relationship satisfaction (McDaniel & Coyne, 2016). As noted by Helsper and Whitty (2010), falling in love, engaging in cybersex, flirting and revealing personal details to other parties were the most agreed-upon online infidelity behaviours.

Another participating spouse shared that they wanted to take revenge on their partner who had been unfaithful to them.

... my husband cheated on me when I was pregnant and so I felt like I wanted to revenge immediately after giving birth because it kept on... like I kept on having this thing in me that... I could not forgive him but then I told him I forgave him but then I just had this thing in me that I need to revenge myself. (Participant R)

You know I would like to.to believe that maybe my partner was doing it to spite me or to pay revenge because.she happens to find me cheating. (Participant D)

Wanjiru, Ireri and Menecha (2020) confirm that infidelity does create a need in the aggrieved partner to want to take revenge when their partner has cheated on them. Women may take revenge and choose infidelity because of their resentment toward their husbands for their husband's wrong deeds (Messripour, Etemadi, Ahmadi & Jazayeri 2016). In the same vein, Ruza and Ruza (2010) implied that revenge hostility emerges in response to infidelity that occurs in retaliation for some perceived wrong by the partner.

The researchers conclude that it is evident that relational and contextual factors play a major role in contributing to extramarital affairs where motivations differ by gender. Every affair is different as reflected in each of the participating spouses' reasons for their involvement in infidelity.

In the next theme, participating spouses describe the challenges they faced because of the marital infidelity they experienced.

Theme 2: Spouses' descriptions of the challenges they faced because of marital infidelity

After participating spouses had given the reasons why their infidelity had occurred, they were asked to describe what challenges they faced because of marital infidelity. Their responses to this question were categorised into three subthemes, namely, financial challenges, lack of trust or respect, and lack of support or communication.

Finances were one of the challenges the participating spouses faced because of marital infidelity.

...one of the greatest challenges I've... experienced greatly was ...the finances you know... to be honest, it's not easy to maintain a double life... I ended up... my roles... ended up changing you know... now I was not going home as frequently as I used to go home... But, on the other hand, I knew what I was doing... and that type of a lifestyle, it needed to be maintained... so that is why it affected my finances. (Participant K)

...the challenges were things like financial struggles... there are certain things that we do for the house... he knows that he needs to take care of the bigger finances in terms of school fees for myself because I'm still a student... and stuff like cars that .are still being financed by banks, so he takes care of that and I take care of little things like groceries and so forth. And... he just completely just stopped doing it and I know for sure that he still can afford it. (Participant I)

Esiri and Chigbu (2014) stated that cheating men spend more money on their mistresses than on their wives. Financial challenges such as reduced income earnings during the infidelity experience, the diversion of household resources to the partner in infidelity, and the economic consequences related to divorce are recognised outcomes of infidelity that impact on marital partners (Crouch & Dickes, 2016).

Participating spouses' biggest challenge resulting from infidelity was lack of trust. Participant T maintained that the lack of trust was the biggest challenge resulting from the infidelity:

I think the biggest of them all would be trust. Rebuild trust is something that to this day... it's difficult. Yeah, because you know I go out to have a social life, I go out at night. So, even when I'm chilling with my friends... it's just a social you know hang out, she wouldn 't be comfortable because one... I'm out. ...at this point I feel like I can trust her almost 90%... with her, I know she doesn't trust me... one bit.

... right now, there is no trust at all.he does not trust me right now because right now ... we are in a long-distance relationship. So, I go home on weekends. So, he does not trust me, he feels I will cheat or do something where I stay right now. (Participant R)

Ojedokun (2015) indicated that an extramarital affair causes unbearable emotional pain and trauma, a blow to self-esteem and a lack of trust or respect. Even if you have admitted your affairs in front of your partner and apologised, you won't be able to regain their trust again as before (Jesse, 2021).

Participating spouses experienced a breakdown of communication and lack of support as one of the challenges faced because of marital infidelity. Participant J identified lack of communication as a challenge she was facing:

Our communication. I don't think we are... I don't think we have constructive conversations. I don't know if we are still planning together because I know she probably has planned; I also have plans but then I don't know if we are still planning together because our communication it's poor now because of trust.

Participant, I identified a lack of support which was linked to a lack of communication as well:

Him not being supportive... when I'm going through certain things... that I would like to share with him... he is absent, and he wouldn't pay attention or even bother to ask have you solved it, you know... how can I help?

When communication is poor, couples experience emotional isolation, neglect, sexual difficulties and uncertainty, and this leads to one seeking intimacy outside the primary relationship, hence infidelity occurs (Mapfumo, 2016). Jesse (2021) stated that the current data on infidelity indicates that males and females cheat as a result of a lack of support as well as problems in marital relationships.

Based on the above, it was concluded the exposure to the identified challenges could be irreparable or take time for the marriage to get back to where it was for both the victim or the offender, their families, or worse, their children.

The next theme presents descriptions of how marital infidelity affected the spouses' marriages.

Theme 3: Spouses' descriptions of how the marital infidelity affected their marriage

After the spouses described how the infidelity in their marriage had affected them personally, they were asked to recount how their marriage had been affected by marital infidelity. The spouses gave a variety of responses, which are presented in the form of storylines sub-divided into four sub-themes, namely: family units were affected; considered divorcing; experienced tension or uncertainty; and a lack of trust or communication.

The participating spouses indicated how marital infidelity affected their family units. Participant K recounted how his roles as partner and father as well as his children had been affected by the infidelity:

... it affected... my roles as a husband and as a father to my children... it affected me in that depth.it affected my children as well because they were used to having me every weekend and then now... suddenly your father is no longer coming home every weekend now, he's coming once a month ...he's at times full of excuses...

Participant D also related how his family life was affected:... also affected our kids in one way or another because they could see that there was something wrong...

Kioko (2015) noted that marital infidelity leads to disintegration of the family unit, which in turn results in poor, physical, mental and moral growth among the family members. It threatens the family structure and consequently the feeling of marital belonging (Baboo & Mohammadi, 2021). Ojedokun (2015) indicated that an extramarital affair has a great negative impact on home stability.

Participating spouses stated that they considered divorce because marital infidelity affected their marriage. Participant R explained that she and her husband had considered divorce:

... we have on many occasions; we've like we've reached a point where we were like we wanted to divorce. He wanted us to go our separate ways but then we came back and thought of our child and then, we just had to resolve our issues right now.

Participant I reported the same consideration of divorce:

...I felt like it is not worth it anymore. I think maybe we should file for divorce or maybe separate... because it's not worth it anymore... it's draining us and believe we are both young and maybe we could do better if we separated or divorced.

The above statements are supported by Russell, Baker and McNulty (2013) indicated that not only may infidelity lead to relationship distress and therefore decreased relationship satisfaction for both partners, but it is also a strong predictor of divorce. Marital infidelity is considered one of the factors jeopardising the performance, stability and the endurance of marital relationships as well as being a main reason the collapse of a marriage (Messripor et al., 2016).

Other spouses reported that they had experienced tension or uncertainty in their marriage because of marital infidelity. Participant D spoke of the tension in the marriage after the infidelity: So.there was just a tension, and the tension also affected our kids in one way or another because they could see that there was something wrong...

Participant N experienced uncertainty when he compared his wife to the person with whom he had been unfaithful:

...it's quite difficult to put it in one as to what extent, but... honestly, I think it devalues... it devalues how you view the other partner you know. Now you start comparing even though you find that your primary partner is doing... it's like you're proving there and there... like you know that knowledge of saying that comparison, you know it ends up making you compare her with the other person. And as such, it has the potential to affect the quality of your union.

Recovering from an affair is one of the most challenging chapters of one's life and the challenge comes with ambivalence and uncertainty (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2021). Gemmer (2012) concurs that when a betrayed partner discovers or is informed about the affair, questions about the entire legitimacy of the marriage arise and, as a result, the betrayed partner often wonders if the entire relationship was a lie.

The researchers conclude that the inability of married couples to resolve their marital problems, which include infidelity, may lead to ineffective communication which has an extensive impact on the marriage.

In the next theme, participating spouses explained how they dealt with the consequences of infidelity.

Theme 4: Spouses' explanations of how they dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity

After having recounted how the marital infidelity had affected their marriage, the spouses were then asked whether or not they had been able to deal with the consequences of infidelity If they had, what were their coping strategies, and if they had not, what were the hindrances or obstacles. The spouses' responses are given under one theme with four sub-themes, namely how they dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity, namely have not dealt with it; separated for a while; was honest with spouse or self; and went for counselling.

Participating spouses who indicated that they have not dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity are discussed below.

Participant I said that lack of support and love from her husband who had been unfaithful had made it difficult to deal with the consequences of marital infidelity:

I think for me it would support because if you're not supporting somebody whom you say you love.it affects that person mentally.because there is an expectation. that I'm expecting that he's going to be supportive and when he is not supportive, I don't think there is love.

When asked if she had dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity, Participant P responded: I don't... not really because... I think I'm angry... I'm still angry.

Rada (2012) stated that the reaction to infidelity depends very much on an individual's personal limits, because for some a single adventure is intolerable and they will divorce.

The participating spouses decided to separate for a while to deal with the consequences of marital infidelity. Participant F explained that it had been hard for her husband to forgive her and they had separated for a while:

...I had forgotten to delete my call log and also my WhatsApp messages from the person I was having an affair with ... so that almost got us divorced as it was hard for my husband to forgive me ...and that was when we nearly got divorced due to this infidelity.

... there was a point where we broke up... she went back home, and I stayed behind for almost two months. Took my kids with her. We stopped all communication, my family tried to intervene... her family tried to intervene ...we were both 'gatvol' of each other you know ... and then you see the kids had to come back home eventually. So, she came back. (Participant T)

The above findings reflect those of Kioko (2015) that infidelity is responsible for most cases of divorce and separation in marriage, because most marriages die with a whimper as people turn away from one another, slowly grow apart and end up divorcing one another.

One participating spouse was honest with himself and that was how he dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity. Participant N struggled at first to deal with his being unfaithful but eventually realised he had to be honest with himself:

...you need to understand that coping is a way of just making yourself feel better because you know what you did... what you are doing is not right. So...by coping it's like trying to dissociate yourself from that experience or even trying to forget you know... you switch it off... but you find it will keep on coming because every time you are with your wife... at the back of your mind you have that thing that says: hey, but you know you are playing tricks.

Walters and Burger (2013) thought such disclosures offer opportunities to renegotiate the nature of the self and the relationship. Participants said they had gone for counselling, and this had been one way they had tried to deal with the consequences of marital infidelity. Going for counselling was how other participating spouses dealt with the consequences of marital infidelity.

... I wanted to rebuild my marriage... and I wanted my wife and me to work on our marriage and put in more efforts you know. And that is whereby at some point I even initiated counselling. (Participant K)

... after our separation, we went... to therapy... It was from the social workers around where we stay that provided us with counselling. (Participant F)

Ojedokun (2015) stated that when infidelity takes place, there is the likelihood that partners are more likely committed to repairing the relationship and are willing to make amends instead of divorcing. By showing up for counselling, clients have taken the first step towards ensuring that infidelity does not define the rest of their lives (Phillips, 2020).

From the extracts above, the researchers conclude that creating a trusting and safe relationship with the clients is necessary to enable clients to share their concerns or experiences with trust and honesty during counselling services, and to deal better with or even ultimately repair their marriage rather than separating.

In the next theme spouses describe the effectiveness of social work support services.

Theme 5: Spouses' descriptions of the effectiveness of social work support services

In this theme, the spouses were asked if they had received social work support services to determine whether such services were helpful or not.

All the participating spouses said they had received social work support services except for Participant N, who said in response:

... for me, it's a matter that I consider cheating to be a private matter, you know. It's not easy for you to go and talk to the social workers. Then I found no importance of consulting with social workers.

This response suggests that every relationship has its ups and downs; unfortunately, many couples wait too long before opting for couples therapy after infidelity and by then the damage has already been done (Pace, 2021). Gemmer (2012) stated that the responses to infidelity include self-help, where one attempts to resolve the infidelity within a relationship without the help of outside influences. This attempt to resolve the infidelity within the relationship without external assistance, suggests that individuals demonstrate their resilience and belief in their own ability to overcome the difficulties they face.

Those who responded by saying they had received or sought social work support services were asked whether these services had been helpful or not. Some spouses said that the social work support services that they received in the form of counselling had enabled them to speak about the challenges they faced in their marital relationship as a result. Participant I said this was the case, specifically for her:

It was counselling, verbally... trying to just suggest stuff and try to get the depth of my... challenges in my marriage... they were very supportive... for me, I think, personally it was [helpful] ...not as for both ...I think it worked differently for me or it helped me a bit... to understand how to deal with this in a better way...

Although Participant K's wife was initially reluctant, he and his wife were able to speak about their challenges and work on building their marriage:

...we received supportive counselling services from a social worker... the lady indeed managed to assist us... she allowed us to become ourselves and to be in a safe space wherein we managed to cough out the challenges that we were hiding from each other.

The findings above are supported by those of Pace (2020), who noted that infidelity counselling not only allows one to take the floor with their hurt feelings, but can also help understand what went wrong in the relationship and how to avoid similar mistakes in the future. In the same vein, Ojedokun (2015) stated that marital and family psychotherapy sessions facilitate communication between partners and prevent a decline in marriage relationships.

Other spouses said that the social work support services they had received helped them to address some issues. Participant D spoke of how he and his wife were helped to see where they had gone wrong and what they needed to address:

Yes, it was helpful because we could... after engaging with the social worker we could see where we went wrong and try to... to amend whatever needed to be fixed in our relationship... we had quite a several sessions and we were grateful that we went to the office of the social worker... had we not gone to the office I don't know where I would be now... we could see that involving the elders that it was not working out so we had to seek professional help. because those people are trained to deal with problems in marriages.

Gemmer (2012) stated that discussing the conflicts in the couple's marriage prior to the extradyadic relationship can promote insight into what may have led up to the affair. One of the responses was that the social work support services were helpful in that the spouses expressed the opinion that the social worker had helped them to understand the situation better.

Yes, they were helpful because right now we... like, we have learnt to trust each other again, we... we do things as a couple right now. Like, we... choose like, no matter, what happens, we chose to choose each other repeatedly... yes and put everything aside. So, the counselling was, was just helpful. (Participant R)

Gemmer (2012) stated that helping couples fully understand what led to extradyadic behaviours is important when addressing infidelity with couples. The best stance for therapists to take is to encourage clients to explore all their feelings about the affair and their marriage or partnership and to help them hold all intense emotions, though not necessarily at once (Koenig 2021).

The researchers conclude that social workers may help young married couples to address the issues that led up to the promiscuous behaviour by applying their skills, knowledge and social work intervention models to repair the marriages on the verge of being broken, or recover those that have already been broken.

There were a few of the spouses participating in this research who responded that the social work support services had not been helpful to them. Two of the spouses responded that their husbands had not attended all the sessions and they felt that the social work support services had therefore not been fully helpful. Participant, I said this:

He... I think only attended a couple of sessions, not all the sessions and I think it's very important for both of us to attend all the sessions, but he didn't attend all the counselling sessions that we were supposed to do together ...it did help.

Participant T explained:

So, what we did as a couple was, we attended one counselling session. That was during the lockdown and the lady... I think she didn't pick sides... the counsellor ... was a lady. She was fair and she [wife] cried more than me. But otherwise, I wouldn't say it was effective to that extent.

Pace (2020) contends that it is incredibly important that both parties commit fully to the process of infidelity counselling for the sessions to be successful. Pace (2021) added that one of the reasons why couples are not eager to start with couples therapy is that one of the two is unwilling to cooperate. Although they did receive social work services, some spouses said they were not helpful and expressed the opinion that it takes time to heal after having experienced marital infidelity. Schnell (2017) mentioned that research shows it takes about eighteen months to two years to heal from the pain of a partner's infidelity.

Suggestions regarding social work support services for couples who have experienced marital infidelity are presented in the next theme.

Theme 6: Spouses' suggestions regarding social work support services for couples who have experienced marital infidelity

After the participating couples had explained whether social work support services had been helpful to them or not, the spouses were asked for their suggestions regarding social work support services for couples who have experienced marital infidelity. In responding to this question, many of the participants focused more on making suggestions about what couples should do rather than on what social workers should do. Consequently, three sub-themes are addressed: social workers should market their services; social workers should be proactive and non-judgemental; and couples should seek and pre- and post-marital counselling.

Many of the spouses' first responses were to suggest that social workers should market their services and be proactive.

...the social workers can also market their services... run campaigns... about marriage... about challenges faced by couples because I believe that this is what they do on their daily basis, they know these things... they get to experience a lot of couples that come to their offices having so many different problems... (Participant K)

I think social workers should market their services, make their services available to everyone. Let the public know what kind of services they are providing because sometimes people are not going to the offices because they don't [know] what services they are going there for ... I think they can save quite a several marriages. (Participant D)

In marketing social work services, Project Search (2011) indicated that social networks can be used to provide relevant information and build partner communication skills about the risks of concurrency; moreover, conflict resolution skills for couples can be developed to improve the quality of relationships, leading to reduced interest in outside partners. Social work and marketing skills sets come naturally and give social workers the power to create a more positive perception of the work they do; in addition, changing how people perceive the profession can both improve the reputation and strengthen the mission of social work (Battista-Frazee, 2021). In other words, marketing social work services can be used to raise awareness of the negative consequences of infidelity, promote healthy relationship dynamics, and provide information about available support services by identifying target groups, understanding their needs and motivations, and designing effective communication campaigns to influence behaviours and attitudes related to infidelity (Moraro, 2015).

Participant N emphasised the need to be proactive and started by referring to strengthening families:

So, for me, I will say... it's for social workers just to intensify their family strengthening programmes, especially for us as young couples because some of us we are not able to... to talk openly about cheating and the likes.

According to Weeks and Treat (2013), therapists must adopt a structured approach, otherwise, the partner who feels being sided against is unlikely to return, and the accusing partner has his or her linear view of the situation reinforced. Therapists should be proactive, non-judgemental, open to alternative lifestyles, consistently observant, and validate and create an atmosphere of hope in the sessions; they should remain sensitive to third parties being affected and minimise any harm or emotional fallout among all the parties concerned, i.e. client, their spouse, their families and their affair partners (Agrawal & Shah, 2009).Social workers must internalise professional values such as respect, individualisation, self-determination and confidentiality as stipulated by Grobler, Schenck and Mbedzi (2013), when dealing with marital infidelity.

Many of the spouses suggested that over and above social workers marketing their services, couples themselves should seek marital counselling when they experience any challenges, but they also suggested that it was important for couples to seek pre- and post-marital counselling from social workers.

And the suggestions to married couples are they should seek post- and pre-marital counselling. That one should always be a priority... (Participant S)

Based on the above statements, the researchers conclude that since social work support services that do not follow a linear process, it is very important to provide pre- and post-marital counselling services to couples who are experiencing or have experienced infidelity in their marriages to improve their wellbeing. Social service providers should also market their services in the sense that all the services required to address married couples' issues are accessible.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SOCIAL WORK

Based on the research findings, several implications for social work practice were identified by the researchers. These provide insights into potential outcomes that should be considered regarding training and education, the social work knowledge base, social work practice and further research. These implications include the need for intervention methods and programmes that are designed to assist young married couples to deal with issues of infidelity to be introduced in social work training at an undergraduate level. Social work practitioners must be well informed about intervention strategies that integrate interactive tasks towards dealing with infidelity amongst young married couples, and policymakers should develop, engage, amend and promote policies that will assist young married couples, their families and communities to fulfil their potential and lead healthy and productive lives.

Further research should be undertaken to determine and explore the best evidence-based approaches or practices that will assist young married couples to better manage the issue of infidelity in marriage. Infidelity is a very sensitive issue and for that reason it is recommended that social workers be proactive and non-judgemental. To ensure this, the following suggestions can help to apply this in practice. Social workers should receive a comprehensive training and education on issues related to infidelity, including its causes, impact and effective intervention strategies. The training should emphasise the importance of maintaining non-judgemental attitudes and developing empathetic skills to better understand the complexities and emotions that accompany infidelity.

Social workers should continually engage in self-reflection and raising their self-awareness to recognise and manage personal biases, values and assumptions when working with clients affected by infidelity. Such introspection will assist social workers to maintain an objective and non-judgemental approach to create a safe and supportive environment in which clients can share their experiences. Social workers should therefore also strive to understand and appreciate diverse cultural perspectives on infidelity. Recognising that cultural norms, beliefs and values related to infidelity can vary, social workers can tailor their interventions accordingly, ensuring they are responsive to the client's unique cultural contexts.

Social workers should emphasise active listening and empathetic communication when dealing with clients affected by infidelity. By actively listening to clients' experiences, concerns and emotions without judgement, social workers create a safe space for clients to express themselves openly and honestly. Social workers should therefore adopt a collaborative approach when working with clients to identify their needs, goals and preferred solutions. By involving the clients in decision-making processes and treating them as active participants, social workers empower their clients to take responsibility for their recovery and growth.

Social workers should engage in continuing professional development opportunities to remain abreast of the latest research, theories and best practices when working with clients affected by infidelity. This continuous learning equips social workers with the necessary tools and knowledge to effectively address issues related to infidelity. By implementing these suggestions, social workers can create an environment of trust, support and non-judgement, and thereby help clients affected by infidelity to overcome their challenges and work toward healing and growth in their relationship.

In conclusion, this qualitative research study provides valuable perspectives on the experiences of infidelity among young married couples in Lepelle-Nkumpi, Limpopo province. The findings highlight the prevalence of infidelity and its repercussions on marital relationships. The study emphasises the importance of pre- and post-marital counselling as essential interventions for young couples to cope with the difficulties linked to infidelity. By providing a supportive framework for understanding and managing infidelity, social workers play a pivotal role in guiding couples through the process of recovery and facilitating constructive change in their marriage.

Overall, this research contributes to an in-depth understanding of the experiences and consequences of infidelity in modern society. It further highlights the significance of proactive measures, such as counselling, to address infidelity-related challenges and prevent marital dissolution. By recognising the specific needs of young married couples in the context of infidelity, social workers can offer guidance and support, enabling couples to navigate the recovery process and ultimately improve the overall quality of their marriage.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, J. & Shah, A. 2009. Couples therapy and extra-marital involvement: Principles and practices. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 25(3-4): 78-88. [ Links ]

Anastas, J. W. 2014. Research on social work practice. 24(5): 571-580. [ Links ]

Baboo, N. & Mohammadi, N. 2021. Investigating the effect of internet addiction on the tendency of marital infidelity in couples in Shiraz. Propositos y Representaciones, 9(2): 1087. [ Links ]

Bahareh, Z. 2011. Review of studies on infidelity. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 19(2): 182-186. [ Links ]

Baloyi, G. T. 2011. Factors influencing resilience in men: Exploring pastoral method of care to an African situation. Doctoral thesis. University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Battista-Frazee, K. 2021. Social workers can create a buzz about their profession. [Online] Available: https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/exc_090915.shtml [Accessed: 15/12/2021]. [ Links ]

Bhattarai, T. 2012. Extramarital affair increase as Nepal society liberalise. Global Press Journal. [Online] Available: https://globalpressjournal.com/asia/nepal/extramarital-affairs-increase-as-Nepal-s-society-liberalizes/ [Accessed: 02/12/2012]. [ Links ]

Carter, C. W. 2014. Infidelity accounts. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(7): 16-23. [ Links ]

Crouch, E. & Dickes, L. 2016. Economic repercussions of marital infidelity. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 36(1/2): 53-65 [ Links ]

Esiri, J. M. & Chigbu, I. O. 2014. Handling marital infidelity: The Hosea example. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 3(1): 424-431. [ Links ]

Fincham, F. D. & May, R. W. 2017. Infidelity in romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13: 70-74. [ Links ]

Fye, M. A. & Mims, G. A. 2019. Preventing infidelity: A theory of protective factors. The Family Journal: Counselling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 27(1): 22-30. [ Links ]

Gemmer, S. J. 2012. Exploring infidelity: Developing the GEM RIM (Gemmer 's Risk of infidelity Measure). Doctoral thesis. Wright State University, United States. [ Links ]

Godswill, O. N. & Natal, A. 2016. Risky sexual behaviour among married and cohabiting women and its implication for sexually transmitted infections in Mahikeng, South Africa. Sexuality & Culture, 20: 805-823. [ Links ]

Gottlieb, L. N. 2013. Strength-based nursing care. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Grobler, H., Schenck, R. & Mbedzi, P. 2013. Person-centred facilitation: Process, theory and practice. 4th ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Harrison, A. & O'Sullivan, L. F. 2010. In the absence of marriage: Long-term concurrent partnerships, pregnancy, and HIV risk dynamics among South African young adults. AIDS Behaviour, 14(5): 1-15. [ Links ]

Helsper, E. J. & Whitty, M. T. 2010. Netiquette within married couples: Agreement about acceptable online behaviour and surveillance between partners. Computers in Human Behaviour, 26(5): 916-926. [ Links ]

Idemudia, E. S. & Mulaudzi, S. K. 2019. Exploring cheating behaviour amongst married men and women in a South African University. Gender and Behaviour, 17(2): 13248-13267. [ Links ]

Jahan, Y., Chowdhury, A. S., Atiqur Rahman, S. M., Chowdhury, S., Khair, Z., Ehsanul Huq, A. T. & Rahman, M. M. 2017. Factors involving extramarital affairs among married adults in Bangladesh. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 4(5): 1379-1386. [ Links ]

Jesse, R. 2021. Who cheats more men or women infidelity statistics (2021). [Online] Available: https://www.dumblittleman.com/who-cheats-more-men-or-women/ [Accessed: 15/12/2021]. [ Links ]

Kioko, R. K. 2015. Determinants of infidelity among married couples in Mwingi central constituency, Kitui country, Kenya (C50/CE/14370/2009). Masters' thesis. Kenyatta University, Kenya. [ Links ]

Koenig, K. R. 2021. When a married client is having an affair. [Online] Available: https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/exc_091809.shtml [Accessed: 11/02/2020]. [ Links ]

Leeker, O. & Carlozzi, A. 2014. Effects of sex, sexual orientation, infidelity expectations, and love on distress related to emotional and sexual infidelity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40(1): 68-91. [ Links ]

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Mapfumo, J. 2016. Unfaithfulness among married couples. Journal of Humanities & Social Science, 21: 110-123. [ Links ]

Marin, R. A., Christensen, A. & Atkins, D. C. 2014. Infidelity and behavioral couple therapy: Relationship outcomes over 5 years following therapy. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 3(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

Masilo, T. D. 2019. Exploring extramarital sexual relationships as a precursor to psychosocial problems: A concern for social work practice. Gender & Behaviour, 17(2): 12791-12800. [ Links ]

Matshidze, P. & Nemutandani, V. 2017. The role of the Vhavenda women in managing marital conflicts in Thulamela Municipality, Thohoyandou: An indigenous perspective. Agenda, 1-10. doi:10.1080/10130950.2016.1266795. [ Links ]

Mayo Clinic Staff. 2021. Infidelity: Mending your marriage after an affair. [Online] Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/infidelity/art-20048424 [Accessed: 15/09/2021]. [ Links ]

McDaniel, B. T. & Coyne, S. M. 2016. "Technoference": The interference of technology in couple relationships and implications for women's personal and relational well-being. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5: 85-98. [ Links ]

Messripour, S., Etemadi, O., Ahmadi, S. A. & Jazayeri, R. 2016. Analysis of the reasons for infidelity in women with extra-marital relationship: A qualitative study. Modern Applied Science, 10(5): 151-162. [ Links ]

Miley, K., O'Melia, M. & Dubois, B. 2009. Generalist social work practice: An empowering approach. 6th ed. United Kingdom: Pearson. [ Links ]

Milhausen, R. R., Janssen, E. & Mark, K. P. 2011. Infidelity in heterosexual couples: Demographic, interpersonal, and personality-related predictors of extradyadic sex. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 40(5): 971-982. [ Links ]

Mohlatlotle, N. E., Sithole, S. & Shirindi, M. L. 2018. Factors contributing to divorce among young couples in Lebowakgomo. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 54(2): 256-274. [ Links ]

Moraro, M. A. 2015. Media campaign and knowledge on extra marital affairs: Case of Mpango Wa Kando advert in Kenya. Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(1B): 110-114. [ Links ]

Myers-Walls, J. A. 2017. Strengthening family resilience. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(4): 584-588. [ Links ]

Negash, S. & Morgan, M. L. 2016. A family affair: Examining the impact of parental infidelity on children using a structural family therapy framework. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(2): 198-209. [ Links ]

Ngazimbi, E. 2009. Exploring the relationship between marital expectation and marital satisfaction between married African immigrant couples and United States born married couples. Doctoral thesis. University of Central Florida Orlando, United States. [ Links ]

Ojedokun, I. M. 2015. Extramarital affair as a correlate of reproductive health and home instability among couples in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Social Work, 5(2): 1-40. [ Links ]

Pace, R. 2020. What constitutes infidelity in marriage? [Online] Available: https://www.marriage.com/advice/infidelity/what-constitute-infidelity [Accessed: 15/01/2021]. [ Links ]

Pace, R. 2021. Recovering from an affair: Couples therapy after infidelity. [Online] Available: https://www.marriage.com/advice/infidelity/couples-therapy-after-infidelity/ [Accessed: 18/12/2020]. [ Links ]

Pattoni, L. 2012. Strength-based approaches for working with individuals. [Online] Available: https://www.iriss.org.uk/resources/insights/strength-based-approaches-working-individuals [Accessed: 11/02/2020]. [ Links ]

Phillips, L. 2020. Recovering from the trauma of infidelity. Counselling Today. [Online] Available: https://ct.counselling.org/2020/04/recovering-from-the-trauma-of-infidelity/ [Accessed: 15/01/2021]. [ Links ]

Pour, M. T., Ismail, A., Jaafar, W. M. W. & Yusop, Y. M. 2019. Infidelity in marital relationships. Psychology & Psychological Research International Journal, 4(2): 1-14. [ Links ]

Project Search. 2011. Understanding the dynamics of concurrent sexual partnerships in Malawi and Tanzania: A qualitative study. Baltimore: USAID. [ Links ]

Pulla, V. & Francis, A. P. 2015. A strength approach to mental health. In: Francis, A., Pulla, V., Clark, M., Mariscal, E. S. & Ponnuswami, I. (eds). Advancing social work in mental health through strength-based practice. United Kingdom: The Primrose Hall. [ Links ]

Rada, C. 2012. The prevalence of sexual infidelity, opinions on its causes for a population in Romania. "Francisc I. Rainer" Anthropology Institute of the Romanian Academy, 58(3): 211-224. [ Links ]

Rautenbach, J. & Chiba, J. 2010. Introduction to Social Work. In: Nicholas, L., Rautenbach, J. & Maistry, M. (eds). Introduction to Social Work. Cape Town. Juta. [ Links ]

Ruark, A., Dlamini, L., Mazibuko, N., Green, E.C., Kennedy, C., Nunn, A. & Surkan, P. J. 2014. Love, lust, and the emotional context of concurrent sexual partnerships among youth Swazi adults. Afr J AIDS Res, 133-143. [ Links ]

Russell, V. M., Baker, L. R. & McNulty, J. K. 2013. Attachment insecurity and infidelity in marriage: Do studies of dating relationships inform us about marriage? Journal of Family Psychology, 27(2): 242-251. [ Links ]

Ruza, I. & Ruza, A. 2010. Causal explanations for the infidelity of Latvian residents in dating and marital relationships. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5(2): 535-547. [ Links ]

Schnell, S. L. 2017. Getting over the hurt of an affair. [Online] Available: https://cwcsf.co./getting-over-hurt-affair/ [Accessed: 15/01/2020]. [ Links ]

Schonian, S. 2013. Perceptions and definition of infidelity: A multimethod study. Master's thesis. University of Nevada, United States. [ Links ]

Sharpe, D. L., Walters, A. S. & Goren, M. 2013. Effects of cheating experience on attitude towards infidelity. Sexuality & Culture, 17: 643-658. [ Links ]

Spitzberg, B. H. 2016. Extramarital Affairs. In: Berger, C. R. & Roloff, M. E. (eds). The International Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Communication. USA: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Stinley, C. M. 2017. Exploring men's motivations and restraints in repeated extramarital sex. Master's thesis. Missouri State University, United States. [ Links ]

Tesch, R. 1990. Qualitative research: Analysis types & software tools. Bristol, PA: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Tsapelas, I., Fisher, H. E. & Aron, A. 2010. Infidelity: When, where, why. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Breda, A. D. 2018. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance to social work. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 54(1): 1-18. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, M. 2020. How to build resilience during difficult times. [Online] Available: www.biznews.com/though-leaders/2020/05/25/build-resilience-difficult-times [Accessed: 12/07/2020]. [ Links ]

Walters, A. S. & Burger, B. D. 2013. 'I love you, and I cheated': investigating disclosures of infidelity to primary romantic partners. Sexuality & Culture, 17: 20-49. [ Links ]

Wanjiru, V., Ireri, N. & Menecha, J. B. 2020. An investigation of the factors contributing to infidelity among married couples in selected mainstream churches in Kikuyu Constituency, Kiambu Country, Kenya. Journal of Psychology & Religious Studies, 2(2): 1-8 [ Links ]

Watson, E. 2019. Unfaithfulness in marriage; What is infidelity? [Online] Available: https://www.brookwriters.com/unfaithfulness-in-marriage-what-is-infidelity/ [Accessed: 11/02/2020]. [ Links ]

Weeks, G. & Treat, S. 2013. Couples in treatment: Techniques and approaches for effective practice. 2nd ed. United Kingdom: Brunner-Routledge. [ Links ]

Article received:22/11/2022

Article accepted: 19/06/2023

Article published: 26/03/2024

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Manare Belsie Ngwasheng was a Master of Social Work student at the University of South Africa (UNISA), and is currently a PhD student at UNISA. Her field of interest is on marriages and families, social work counselling, couple counselling, and qualitative research. The article resulted from her masters, conducted from January 2020 to December 2022, and she conceptualised the study, conducted fieldwork, interpreted the findings, and wrote the initial draft of the article.

Rembuluwani Paul Mbedzi is an Associate Professor and Head of the Social Work Department at the University of South Africa. His fields of specialisation and interest includes amongst others, marriage and family support services, couple counselling and divorce. He supervised the study from January 2020 to December 2022 and also assisted with the interpretation of the research data and the conceptualisation of the article.