Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.60 n.1 Stellenbosch 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/60-1-1252

ARTICLES

The relationship between food insecurity, the child support grant and childcare arrangements

Babalwa Pearl Tyabashe-PhumeI; Rina SwartII; Wanga Zembe-MkabileIII

IUniversity of Cape Town, Department of Health and Rehabilitation, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4004-6436 tyabashe.b@gmail.com

IIUniversity of the Western Cape, School of Public Health, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7786-3117 rswart@uwc.ac.za

IIISouth African Medical Research Council https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4106-4513 Wanga.Zembe@mrc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Food insecurity is endemic in South Africa because of high levels of poverty. Children in food-insecure households may be exposed to childcare instabilities. However, the role of social protection in mediating the relationship between food insecurity and childcare arrangements is not well understood. This study explored the relationship between food insecurity, childcare arrangements and the child support grant (CSG) in a township in Cape Town. The study design was mixed-methods; a hunger scale was administered to 120 participants and in-depth interviews conducted with 23 primary caregivers of children under 2 years of age. The findings indicated that despite being food insecure, many households had stable childcare arrangements, presumably because of the CSG and the age of the children at the time of the study. Further research is needed to unpack the relationship between food insecurity, childcare arrangements and the CSG.

Keywords: childcare arrangements; child support grant; food insecurity

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that in South Africa 34.5 percent of the population are children aged 17 years and younger. Of those, the majority are in the youngest age group of 6 years and younger (Statistics South Africa, 2019). Children are an integral part of any community, and because of their vulnerability and their dependence on others, their rights should be protected at all times. Childcare refers to the care, supervision and nurturing of a child by a parent, caregiver or family member(s). It can also be provided in a formal setting by trained caregivers such as those at early childhood development (ECD) centres and foster care centres. According to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, 2006), childcare is not limited to the child's parents exclusively; caregivers can be people who are either related or not related to a child (NICHD, 2006; Phillips & Adams, 2016). There are various types of childcare, including parental care, maternal care and alternative care.

According to Statistics South Africa (2023) the percentage of children who live with their parents, guardians or other adults increased from 57,8% in 2019 to 64,6% in 2021. During the same time, the percentage of children who attended Grade R, pre-school, nursery school, crèche and edu-care centres decreased from 36,8% in 2019 to 28,5% in 2021 (Statistics South Africa, 2023). Additionally, good childcare is recognised as sound parenting, nurturing and psychosocial support that a child receives from a parent or caregiver (Sherr, Macedo, Tomlinson & Cluver, 2017). According to the NICHD (2006), positive caregiving behaviours are essential for meeting the child's developmental needs.

Understanding child development through the lens of the ecological systems theory

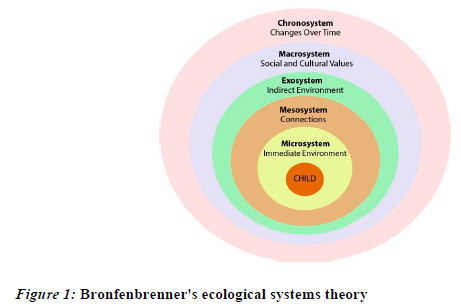

According to Sherr et al. (2017), the quality of parenting and childcare impact on a child's development. The ecological systems theory (Figure 1) developed by Bronfenbrenner looks at a child's development within the context of the system of relationships that constitute their environment. The ecological systems theory has five levels: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). Within the microsystem there are the family, school, neighbourhood and childcare environments. At this level, the child is influenced by the people in their immediate environment, the influences at this level are strongest and have the greatest impact on the child and their development (Paquette & Ryan, 2009). The mesosystem level indicates the connection between the structures of the child's microsystem (Paquette & Ryan, 2009); unrelated people in the microsystem are connected -for instance, the connection between the child's parents and their teacher.

The exosystem level refers to society at large, within which the child does not function directly. For instance, the parent's work schedule may influence the parent's availability and interaction with their child (Berk, 2013). The macrosystem refers to the outermost layer in the child's environment. This level comprises cultural values, customs and laws (Berk, 2000; Berk 2013). The effects of larger principles defined by the macrosystem have a cascading influence throughout the interactions of all other layers. For example, if it is the belief of the culture that parents should be solely responsible for raising their children, that culture is less likely to provide resources to help parents (Paquette & Ryan, 2009). The chronosystem encompasses the dimension of time relating to a child's development and environments. Elements within this system can either be external, such as the event of a parent's death, or internal, such as the physiological changes that occur with the aging of a child. As children get older, they may react differently to environmental changes and may be more able to determine how that change will influence them (Paquette & Ryan, 2009).

Therefore, child development is influenced by the nature of the care that children receive at all levels; this means that the care that the parent or caregiver provides to a child at each level has an influence on the child's holistic development. While early studies emphasised the need for maternal care solely, more recent studies have shown that other childcare arrangements do not necessarily produce negative outcomes (Del Boca, Piazzalunga & Pronzato, 2014; Pilarz, Sandstrom & Henly, 2022). Most of the literature on childcare arrangements and child outcomes over the last few years shows that children's outcomes, including cognitive, health and behavioural outcomes, are the result of inputs provided by people at all levels of the child's environment (Del Boca et al., 2014). Other factors that affect parents' or caregivers' ability to provide care to their children include poverty, the socio-economic status of the household and childcare instabilities.

Living in poverty is associated with poor child outcomes, influenced by quality of parental care, family dynamics and environmental characteristics. Childcare instabilities occur when a child in a particular household is taken care of by different people or attends different childcare centres over a period of time. Childcare arrangement instabilities can have an impact on the quality of care provided to the child (Byrne & O'Toole, 2015; Pilarz & Hill, 2014). Stability and continuity in childcare promote positive interactions between children and caregivers as well as the development of secure attachment relationships. Studies suggest that parents, particularly those with low incomes, often find it difficult and stressful to manage changing employment demands and childcare arrangements. In the South African context, the historical migrant labour system has normalised the separation of families, including children from their mothers (Makiwane, 2011). However, not all changes in childcare arrangements are harmful to children's development. Changes that are planned and purposeful and that lead to higher-quality or more developmentally appropriate care, such as transitioning from in-home care to centre-based care during the preschool years, may produce more positive outcomes (Ansari & Winsler, 2013).

There are other various factors that may adversely affect childcare and development. These include socio-economic factors, such as food (in)security, economic circumstances (especially poverty), parental involvement and living conditions (Hobbs & King, 2018). Poverty is a global problem that affects many households. In South Africa there is a huge number of households that are affected by poverty. Approximately 30.3 million people are living in poverty in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2023). Zembe-Mkabile et al. (2015) mention that there is a higher proportion of children living in poverty than adults, with children generally exposed to higher levels of poverty than adults. There are many poor households in South Africa and hence children are the ones who are mostly severely affected. According to Statistics South Africa (2021), 44% of children (8.9 million) lived in poverty in 2018, and 33% (6.6 million) were below the food poverty line, meaning that they were not getting enough nutrition. This indicator shows the number of children living in households that are income poor. As money is needed to access a range of services, low income is often closely related to poor health, reduced access to education, and unhealthy physical environments.

Social protection mechanisms such as the child support grant (CSG) have been used as a policy instrument to reduce childhood poverty. Few studies have assessed the continued impact of the CSG, and even fewer studies have investigated the role of the CSG in the nexus between food security and childcare. The study reported in this article proceeded from the assumption that food-insecure families are most likely to face childcare arrangement instabilities, because caregivers spend less time with their children as they have to look for work or generate an income for their households. However, the presence of the CSG might mediate the impact of food insecurity on childcare arrangements.

In this article we report results from a study that aimed explore and assess the relationship between food insecurity, childcare arrangements and the child support grant among a cohort of mother-child pairs who participated in a longitudinal study. This study's objectives were i) to explore the extent of food insecurity among CSG recipients and non-recipients; ii) to explore the extent to which food insecurity contributes to childcare arrangement instabilities; and iii) to explore and compare the relationships between childcare arrangement instabilities and food insecurity among CSG recipients and non-recipients.

METHODOLOGY

This study proceeded from the assumption that food insecure families are most likely to have childcare arrangement instabilities because caregivers spend less time with their children as they have to look for work or engage in income-generating activities that take them away from home. However, it hypothesised that the CSG may mediate the impact of food insecurity on childcare arrangements. The study design was an explanatory, sequential mixed-method design. This is a design in which quantitative and qualitative data are collected sequentially and analysed separately, with the qualitative data explaining the quantitative results (Cameron, 2009). This study design was two-phased; the quantitative data were collected and analysed first and then the qualitative data were collected. This was done so that the qualitative data could build on the results emanating from the quantitative data. The two-phase structure and the link to emergent approaches where the second phase was designed on the basis of the outcomes of the first phase (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011).

The sample of this study was drawn from a larger research project, a longitudinal birth cohort study which investigated the impact of the CSG on child health and wellbeing outcomes in an urban township in Langa, Western Cape Province. About 500 children under the age of 2 made up the birth cohort sample. The sample size calculations were done with the assistance of a senior biostatistician. The comparison of the primary outcome, height for age (HAZ), between CSG recipients and non-recipients at 2 years of age was used to calculate the sample size required for the primary study. The study proceeded on the basis of a number of assumptions. It was expected that at 2 years of age, 80% of the established cohort would be CSG recipients. This implied an expected ratio of 4:1 in the size of the two groups. At 2 years, it was expected that the mean HAZ=-.8 for CSG recipients and the mean HAZ=-1.0 for non-recipients. Therefore, the expected difference was 0.2 standardised deviation units. A common standard deviation for both groups of 1.5 units, at 90% power and a significance level of 5% using a 2-sample t-test in the statistical analysis.

Under these assumptions the total sample size needed to be 305 participants, consisting of 244 CSG recipients and 61 non-recipients. To make provision for inability to follow up at two years, the sample size was increased to 500. The population for this study was mothers who were identified and recruited while pregnant (+- seven months) at Langa Clinic and Vanguard Community Health Centre. These are the community clinics which provide health care services for the people living in Langa. The mother and child pairs were followed up from six weeks after birth and data were collected at three-six weeks, at six months, at one year and at two years of age. The sample for this study was selected purposefully. It included all participants followed up for the primary study over a period of three months (March to June 2018) and provided a sample of 120 mother-child pairs. All these participants completed the household hunger scale (HHS). The SPSS software was used to analyse and tabulate demographic data and the HHS categorical indicator was used to determine food-insecure households.

A follow-up was done on the quantitative results in order for the second phase to be implemented - which was where the quantitative and qualitative data were connected. The sample for the qualitative data collection was purposefully selected from the quantitative results. Participants who were deemed food insecure on the basis of the HHS analysis formed the pool from which 23 participants were selected for the qualitative key information interviews. These participants provided an in-depth account of their lived experiences. Additionally, three focus groups were conducted with 24 community workers (care workers) who were also mothers and were not participants in the cohort study. Each focus group consisted of eight participants. The qualitative data were thematically analysed with the aid of ATLAS.ti. After that, both the quantitative results and qualitative findings were integrated and interpreted.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSSREC) of the University of the Western Cape (reference HS18/4/20). The component of the study relating to the hunger scale was submitted as an amendment to the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) since the sample on which the scale was administered came from the primary study.

Validity and Trustworthiness: The researcher used bracketing (i.e., writing down preconceived ideas and beliefs prior). This was done for the purpose of later reflection and to avoid bias. A peer review process was also followed to ensure the trustworthiness of the study. In this regard, the researcher worked with the fieldworkers to verify that the HHS data were analysed correctly.

FINDINGS

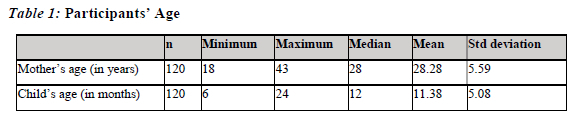

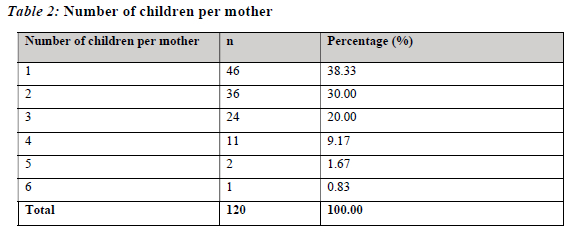

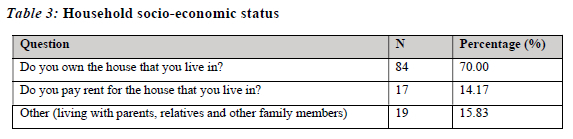

The purpose of the quantitative component of the study was to ascertain the demographic characteristics of the respondents and to identify households that were food insecure. The demographic data indicated the age of the sample (Table 1), number of children per mother (Table 2) and the socio-demographic status of each household (Table 3).

Participating mothers had between one and six children (Table 2). The majority of the 46 mothers (38.33%) had only one child, while one mother (0.83%) had six children.

Findings revealed that 31.67% of the participating mothers earned money for themselves, 49.16% did not earn money and 19.16% did not disclose, when asked if they earned money for themselves. Three additional questions were asked in order to determine the means by which the participants received their income. Some 9.17% of participants earned money through irregular employment, 17.5% earned money through regular employment and 1.67% earned money through home employment.

In addition to the socio-demographic data, the results also revealed the socio-economic status of the participants regarding their housing and basic household utilities. Seventy percent (70%) of the participants owned the houses (formal and informal) that they lived in, 14.17% paid rent and 15.83% lived with their parents, relatives and other family members (Table 3).

The extent of food insecurity among CSG recipients and non-recipients

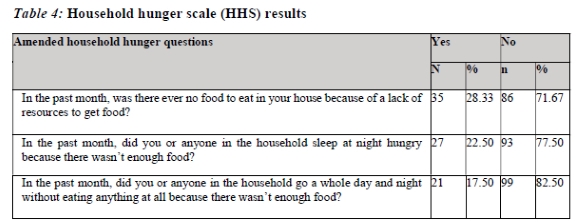

According to Ballard, Coates, Swindale and Deitchler (2011:1), "the household hunger scale (HHS) is used to measure household hunger in food insecure areas". The HHS has three main questions, with sub-questions used for follow-up purposes. Acquiring answers to these questions helped to distinguish participants who were food secure and those who were food insecure. Data collected with the HHS were analysed to construct two types of indicators: a categorical HHS indicator and a median. To tabulate both indicators, it was first necessary to compute an HHS score for every responding household. This required some recoding of the data collected (Ballard et al., 2011). Table 4 below lists the amended household hunger questions and the responses to them. The majority of the sample reported little to no hunger in the households (Table 4), while 28.33% reported that in the past month there had been instances when there was no food in the household because of the lack of resources to get food. A further 22.5% reported having gone to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food, and 17.5% reported that someone in the household had gone the whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food.

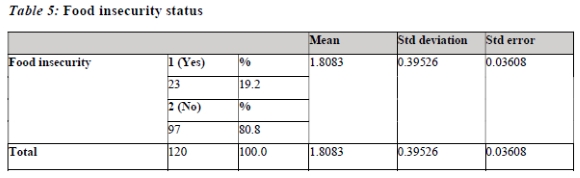

The HHS was administered to 120 participants; 23 participants (19.2%) were found to be food insecure, and 97 participants (80.8%) were found to be food secure. The standard deviation for this sample was 0.39526 and the standard error was 0.03608.

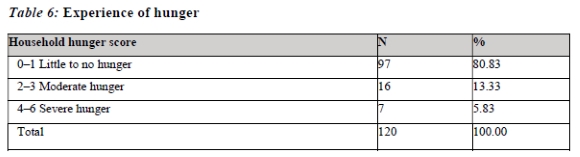

In the third step, the new variables were summed for each household/participant in order to calculate the HHS score. Ballard et al. (2011) mention that the correct tabulation should reflect the HHS score of 0 to 6 and state that a score of 0-1 indicates households where there is little to no hunger; a score of 2-3 indicates households with moderate hunger; and a score of 4-6 indicates households with severe hunger. The food-insecure participants had scores of 2-6. Of the food insecure, 5.83% (n=7) experienced severe hunger (Table 6).

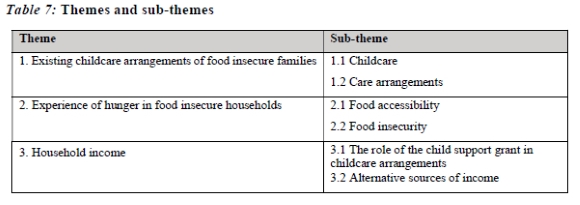

The 23 participants who were identified as food insecure were invited to participate in the qualitative component of the study. As mentioned previously, food insecurity can be the result of different factors. The qualitative data were analysed and during the analytical process themes that were generated by the interviews were identified, arranged and summarised. These appear in Table 7 below. Findings from this study will be first presented under a theme, followed and substantiated by a comment from either an individual interview or focus group discussion.

Theme 1: Existing childcare arrangements of food insecure families

Findings revealed that childcare arrangements in food-insecure households are not straightforward; they do not allow for a simple binary analysis of "yes, there are care arrangement instabilities" or "no, there are no care arrangement instabilities". While in many of the households interviewed children lived with their biological parents (often mothers), the extended family played a big role in child rearing, with mothers often sending their children to live with grandmothers, sisters and other relatives for short periods of time.

Sub-theme 1.1: Childcare

Findings indicate that children in most food-insecure households were taken care of by their parents as primary caregivers, while the extended family often assisted in taking care of these children, especially grandparents. Single motherhood was prominent in the interviews, with participants often citing that grandmothers were the ones who stepped in to close the gap left by absent fathers. The findings reflected that mothers as primary caregivers sometimes struggled as they had to look for employment. Not having a secondary caregiver or the father of the child present made it very challenging for the mothers, as they had to leave their children in the care of other people. The participants illustrated this point by stating that:

Sometimes, when I have to go to town to look for a job, I leave my daughter with my neighbour. She also does the same; she also leaves her child with me when she has to go somewhere or when she has commitments.

Focus group discussions' findings indicated that most parents from poor households leave their children with their grandparents in the rural areas and move to urban areas to seek employment. Some food-insecure parents send their children to live with their grandparents or other relatives so that they can look for or engage in employment and income-generation activities; in such cases the CSG would follow the child, while the mother would lose the CSG as a source of income. It was also found that some mothers, after giving birth to their children, struggled to care for them. They chose to send them to the Eastern Cape to live with their grandparents, because there the children would receive better care than they would otherwise have received if they lived with their parents in poverty. These findings highlight that there are different types of caregivers - they can be the parents or the grandparents of the children, depending mostly on their day-to-day experiences and living conditions. Some living conditions may hinder a caregiver's ability to provide adequate childcare. Furthermore, these findings show that socio-economic factors affect the quality of childcare and that these factors may also lead to childcare arrangement instabilities.

Sub-theme 1.2: Care arrangements

The findings from this study suggest that most children in these households spent most of their time with their parents and were rarely taken care of by other people for long periods of time. However, some parents chose alternative care arrangements for their children when they had to run errands or when they looked for jobs or went to work. In addition, the most desirable alternative care arrangement based on the findings was to leave a child in the care of a relative. In some instances, parents relied on their neighbours for alternative childcare, because they also assisted their neighbours by taking care of their children. This shows unity in the communities and a spirit of ubuntu. However, the findings show that some parents chose these alternative care arrangements because they could not afford to pay for other arrangements such as ECD centres and child minders. The participants were asked if they would choose the same alternative care arrangements if they were employed or if they had money. Below is an example of one of the responses:

I would take him to a crèche. I love crèches because children get to be with other children, and they get to learn. Unlike when they are with child minders, there they don't get the simulation that is appropriate for their age and growth.

Findings further highlight that money plays a huge role in the care arrangements that parents choose for their children. Most parents indicated that if they had adequate money, they would choose different care arrangements for their children. They would choose arrangements that would be beneficial for the child's overall growth and development.

Theme 2: Experience of hunger in food insecure households

As shown in the quantitative findings above, 78.2% of food-insecure households experienced moderate hunger and 21.8% of these households experienced severe hunger on a daily basis. Some participants mentioned that they eat only once or twice per day:

We eat once or 2 times a day, but it's mostly once. We are used to it now.

We eat 2 or 3 times, it all depends on how much food we have.... I feed my baby whenever he's hungry, so I think he eats 4 or 5 times a day

Hunger in these households was mainly caused by the inability to access enough food for the household. The findings from this study also show that most of these households were unable to source and acquire enough food to consume on a daily basis.

Sub-theme 2.1: Food accessibility

Findings show that these households accessed food in various ways besides earning money from their jobs. The qualitative questionnaire explored ways in which the participants accessed food. Some participants mentioned that they buy food at a local supermarket, but sometimes they take it on credit and other times they go to the food market close by to pick up food that was thrown away but still salvageable.

I take some food items on credit at the spaza shops and then pay them back month end. I also go to pick up food from the market or ask my neighbour for food, more especially for my children.

Some people from these households go to the fruit and veg market in Epping to pick up spoilt fruits and vegetables and salvage them so that they can at least go to bed with something in their stomach.

These quotes indicate that most of the participants found it challenging to access food; they even went to extra lengths to pick up food that was thrown away at the markets. These food items were thrown away because they had expired, but they could be salvaged as something to eat. These findings show food inaccessibility as one of the factors contributing to household food insecurity.

Sub-theme 2: Food insecurity

The findings from this study demonstrate that having low or no income is very challenging and leads to such households being food insecure. Poor households use different strategies to try and stretch the few resources that they have to obtain food. In some households, everyone contributes the little that they have towards providing food. One interviewee elaborated on this:

We all contribute money towards buying the food. Since my mother receives more money than us, she is the one who contributes more money than others and the rest of us contribute a small amount of money. Each and every one of us who receives CSG contributes R75 towards groceries.

These findings show that a little does go a long way; the little money that they had was used to buy food. Findings further highlight that participants from food-insecure households often bought staple foods which did not last the whole month. Food in these households ran out shortly after it was purchased. Participants were therefore asked about the types of food that they bought, and they listed maize meal to make pap and soft porridge, vegetables, tinned fish (pilchards), samp and bread. The food items that they bought and consumed daily were not of a high nutritional value. They bought food that would fill up their stomachs and give them the energy that they needed to get by. The findings also reveal that some parents engaged in shielding their children from hunger through meal skipping or rationing in order to ensure that their children ate at least three times a day, even if the diet was poor.

The impact of food insecurity on childcare arrangements

The findings from this study reveal the role that food insecurity plays in childcare arrangements. The participants from the focus group discussions were asked about household hunger and how they thought it affected the existing childcare arrangements. They mentioned that:

Not having food in the household is very challenging because you end up giving your child away. Not that you want to, but because of circumstances you send your child away to live with other relatives. It is really painful to see your child cry because they are hungry and there's nothing you can do about it.

It is very hard having your child live with you when you don't have food in the household. The child doesn't understand whether there's food or not, when they are hungry, they need to be fed. That's why as a parent you end up sending your child to the rural areas to live with their grandmother because there's no food at home.

The above comments show that food insecurity plays a part in parents sending their children away or leaving them in the care of other people. These findings further illustrate that little or no food in the household is a driving force behind parents choosing alternative care arrangements for their children.

Theme 3: Household income

There are potentially various sources of income in food-insecure households. These include income from employment, social grants and child maintenance money. Most families who are destitute depend on the social security grants that the government provides, including the CSG and the Old Age Grant (OAG) that grandparents receive. Families from this study received the grants as their primary source of income.

The CSG is very helpful, you know. It is my only source of income so I rely on it for everything. I buy food with it.

Furthermore, this study revealed that the CSG was an additional form of income that was used as a substitute for employment income in some households. Overall, child support grants were used to help alleviate childhood poverty in families, address food insecurity and also cater for other household expenses. The provision of cash enhances the family's ability to take better care of their children, even though the CSG is inadequate. The amount is too small and is used for too many expenses which go beyond the needs of the child.

Sub-theme 3.1: The role of the CSG in childcare arrangements

The findings from this study show the relationship between the CSG and childcare arrangements; parents who were CSG recipients chose more stable care arrangements for their children. One participant from the focus group discussion mentioned that:

The CSG plays a huge role in a sense that parents are able to keep their children, because they are able to provide food for them. If it wasn't for this money there would be no food in the household. The parents would send their children away to their well-off relatives.

The CSG money was used interchangeably by parents for their care arrangements. On the one hand, some parents used the money within their households to provide for their children's basic needs instead of sending them away because of their inability to satisfy such needs. On the other hand, some parents used the CSG money to pay for alternative care arrangements; for instance, some participants used the CSG money to pay the fees at the ECD centres. Moreover, there were some parents who were able to keep their children in their household with them because there were other sources of income besides the CSG.

Sub-theme 3.2: Alternative sources of income

Findings from this study indicate that in food insecure households, families also rely on other types of social security grants as their source of income. Participants were asked about alternative forms of income, besides the CSG. They mentioned that:

I am not employed, my mother receives the old age grant and we use most of her money to pay for most of the things.

I live off the CSG that I receive for my children and the foster care grant that I receive for my niece.

I don 't receive the CSG for my oldest daughter because she is 18 now but I receive it for my other 3 children and my daughter receives it for her child. In fact, for my 2nd born I receive a disability grant, as he is physically disabled. His money is the most helpful out of the 3 that I receive because it's a lot compared to the CSG. With the disability grant I am able to do a lot of things that I can't do using the CSG.

These findings clearly show that the other social security grants are used to support multigenerational households. In addition to the old age grant, some families relied on the foster care grant and the disability grant as source of income.

Overall, these findings highlight the fact that the food-insecure households had various sources of income. Although the majority of the participants were unemployed, they did have other means of getting an income and providing for their children's basic needs. Therefore, from these findings it can be deduced that the main source of income was the CSG, because the majority of these households received the CSG as their primary income. Other grants, such as the old age grant and disability grant, were used as additional sources of household income.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to explore the relationship between food insecurity, the CSG and childcare arrangements. The HHS was administered to determine which households were food insecure. The results indicated that of the 120 households, 23 were found to be food insecure, with the latter experiencing moderate to severe hunger. A link was established between the child support grant (CSG) and the hunger experienced in food-insecure households. It was found that in households that received the CSG, hunger was not experienced as severely as in households where there was no CSG recipient. Thus, households with CSG recipients consumed more meals per day than those which did not receive the CSG.

The literature on the role that food insecurity plays in child care arrangements is limited. In view of this, this study set out to determine the link or relationship between the two. A key finding was that food insecurity played a part in parents sending their children away or leaving them in the care of other people. Furthermore, having little or no food in the household was a driving force behind parents choosing alternative care arrangements for their children. Pilarz et al. (2022) mention that children in low-income families may also be more likely to suffer the effects of childcare instability, as well as instability in other aspects of their lives. Some research studies confirm this view by suggesting that parents, particularly those earning a low income, often find it difficult and stressful to manage changing employment demands and childcare arrangements (Adam 2004; Pilarz et al, 2022).

Findings from this study did not suggest any childcare arrangement instabilities. Contrary to the assumption that children in food-insecure households tend to experience care arrangement instabilities, this study showed that the care arrangements for the majority of children in these households were quite stable as almost all the children were taken care of by their parents. However, what seems to explain the absence of care arrangement instabilities is, somewhat ironically, unemployment. An overwhelming majority of mothers sampled for this study were unemployed and thus spent much of their time at home. These findings suggest that children from low-income or food-insecure households are most likely to have stable care arrangements because their parents are unemployed and thus spend more time at home.

In most food insecure households, children were taken care of by their parents as primary caregivers while the extended family often assisted in taking care of the children, especially grandparents. In those households, mothers were the sole caregivers to their children and sometimes struggled in their role as they had to go and look for work. As a result, they often relied on their parents (grandparents), other relatives and neighbours to help them care for their children. A study conducted by Ntshongwana, Wright and Noble (2010) confirms these findings by highlighting that in South Africa, single mothers are often not able to be sole caregivers to their children, because they have to move away from their homes to bigger cities in search of employment opportunities, or have to be absent from home for many hours during the day to go to work or to look for work; as a result, they need to leave their children in the care of their grandparents. Makiwane (2011) supports these findings, by asserting that grandparents among black South African families tend to take care of their grandchildren when their parents migrate from the rural areas to the urban centres to look for job.

The literature suggests that parents from low-income households will not tolerate destitution and food insecurity, and will thus go out and look for work, and this could in turn lead to care instability (Pilarz et al., 2022). It also assumes that where there is care instability, there is food insecurity. The findings from the current study complicate this simple hypothesis in the literature, which assumes that low socio-economic status is central to adverse childhood outcomes and that much centres on whether the parent is available or not. The findings from the current study, however, show that this is not necessarily the case.

The literature on the role that food insecurity plays in childcare arrangements is limited. In view of this, this study set out to determine the link or relationship between the two. A key finding was that food insecurity played a part in parents sending their children away or leaving them in the care of other people. Furthermore, having little or no food in the household was a driving force behind parents choosing alternative care arrangements for their children. Adam (2004) mentions that children in low-income families may also be more likely to suffer the effects of childcare instability, as well as instability in other aspects of their lives. Some research studies support this view by suggesting that parents, particularly those earning a low income, often find it difficult and stressful to manage changing employment demands and childcare arrangements (Adam 2004; Altman, Hart & Jacobs, 2009). Contrary to those studies, findings from this study suggest that children from low-income or food insecure households are most likely to have stable care arrangements because their parents are unemployed and thus spend more time at home.

The findings further highlighted the fact that alternative care arrangements were not the primary child care arrangements in food-insecure households. They were only resorted to when parents had to be away from their children for a few hours in a week or month. This may be due to the fact that when the data were collected, the majority of children were still young and were not at an age where their mothers could leave them with someone else. Many households in the study had multiple generations in them, thus ensuring the mother had extended support to care for their child - this could also explain why, in addition to the protective effect of the CSG, the mothers took longer to leave their children in search of work or to engage in employment.

These seemingly contradictory findings can be explained in different ways. One possible explanation is that parents who are unemployed, living in poverty and confronted with food insecurity attempt to keep their children with them for as long as possible before sending them off to live with relatives if their circumstances do not change. As the data were collected when many of the children were still very young (under the age of 2 years), it may have been too early to observe this shift. However, at the end of the primary longitudinal birth cohort study in 2020, loss to follow-up (attrition) was 35%, as a result of children being moved to live with relatives; they were mainly sent to the Eastern Cape to live with their grandparents. Another explanation is that social grants play a role in helping to maintain childcare arrangement stability, since unemployed caregivers are able to keep their children because of the (albeit small amount of) money coming in.

The results also indicated that people living in food-insecure households had various sources of income, despite being unemployed. They largely relied on the CSG and/or the OAG as their sources of income (Altman et al., 2009; Devereux & Waidler, 2017; Makiwane, 2011), but supplemented their social grants income with casual work or "piece jobs" such as doing laundry for neighbours, or cleaning houses once or twice a week, or selling fruit and vegetables. The child support grants were used to help alleviate childhood poverty in families, address food insecurity and also cater for other household expenses. It is evident from these findings that parents who were CSG recipients chose more stable care arrangements for their children.

Overall, the quantitative and qualitative findings showed that there is a relationship between food insecurity, childcare arrangements and the child support grant. A key finding was that in most food-insecure households, the childcare arrangements were stable. This was generally because the primary caregiver of the child was the parent (mother) and a CSG recipient who used the grant money to buy food in order to reduce household hunger. In some cases, the CSG reduced the risk of childcare arrangement instabilities, as some parents used the money to pay for a stable alternative care arrangement for their child. If the child was not with them, they should ideally be at an ECD centre or with a trusted family member. This highlights how the CSG can be an instrument of stability as far as care arrangements are concerned. Importantly, the CSG money also had a major role to play in addressing the risk or reality of household food insecurity. The CSG therefore enables low-income mothers to provide care for their children when they are still very young; when they are older, they start to send them off to live with relatives to enable the mothers to look for work or to engage in work.

Generally, it can be deduced from the findings that fixed, long-term alternative care arrangements were not the primary childcare arrangements in these food-insecure households. These alternative care arrangements were pursued only when parents had to be away from their children for a few hours in a week or month. Having different and inconsistent childcare arrangements can lead to childcare arrangement instabilities. However, this did not seem to be the case with these households as the parents spent most of their time with their children because they were unemployed; this could be explained by the age of the children at the time of the study.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The quantitative and qualitative components of the study have delivered valuable insights into the relationship between food insecurity, the child support grant and childcare arrangements in the township of Langa. The study provides the foundation on which a series of recommendations, notably in the area of social policy and social work interventions, could be made where there are clear gaps.

The study recommends that more social workers should take up the challenge to ensure that such communities have access to social services that effectively combat social injustices. Effective, inclusive childcare policies and strategies, which inform social work practice, should be based on relevant and reliable data and be formulated in consultation with child caregivers.

In conclusion, this study will be a valuable addition to the existing body of knowledge on food insecurity, childcare and the child support grant, and how these relate to one another. It will also inform good social work practice at the micro, meso and macro levels. Further research is recommended to more precisely unpack the relationship between the CSG, food security and childcare arrangements - studies that will include older children or follow children from birth until they are older to see whether the childcare arrangements change over time and how the role of the CSG evolves with these changes.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) / National Research Foundation (NRF) Centre of Excellence in Food Security.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the mothers and children who participated in this study. We also wish to acknowledge the SAMRC Child Support Grant Longitudinal Cohort Study, from which participants for this study were sampled.

REFERENCES

Adam, E. K. 2004. Beyond quality: Parental and residential stability in children's adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(5): 210-213. [ Links ]

Altman, M., Hart, T. & Jacobs, P. 2009. Household food security status in South Africa. Agrekon, 48(4): 345-361. [ Links ]

Ansari, A. & Winsler, A. 2013. Stability and sequence of center-based and family childcare: Links with low-income children's school readiness. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(2): 358-366. [ Links ]

Ballard, T., Coates, J., Swindale, A. & Deitchler, M. 2011. Household Hunger Scale: Indicator definition and measurement guide. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II Project, FHI 360. [ Links ]

Berk, L.E. 2000. Child development. 5th ed. Boston, USA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Berk, L. E. 2013. Child development. 9th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In: Husen, T. & Postlethwaite, T. N. (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Education. Vol 3, 2nd ed. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Byrne, D. & O'Toole, C. 2015. The influence of childcare arrangements on child wellbeing from infancy to middle childhood. A report for TUSLA: The child and family agency. Maynooth University. [ Links ]

Cameron, R. 2009. A sequential mixed model research design: Design, analytical and display issues. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 3(2): 140-152. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. 2011. Designing and conducting mixed method research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Del Boca, D., Piazzalunga, D. & Pronzato, C. 2014. Early childcare and child outcomes: The role of grandparents. Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study. Families and Societies: Working paper series, 20: 1-33. [ Links ]

Devereux, S. & Waidler, J. 2017. Why does malnutrition persist in South Africa despite social grants? Food Security SA Working Paper Series No.001. DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, 1: 1-35. [ Links ]

Hobbs, S. & King, C. 2018. The unequal impact of food insecurity on cognitive and behavioral outcomes among 5-year-old urban children. Journal of Nutrition, Education and Behavior, 50: 687-694. [ Links ]

Makiwane, M. 2011.The burden of ageing in South Africa. ESR Review, 12(1): 1- 2. [ Links ]

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). 2006. The NICHD study of early child care and youth development: Findings for children up to age 4½ years. USA: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Online] Available: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/documents/seccyd_06.pdf [ Links ]

Ntshongwana, P., Wright, G. & Noble, M. 2010. Supporting lone mothers in South Africa: Towards comprehensive social security. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

Paquette, D. & Ryan, J. 2009. Ecological systems theory. Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory: National-Louis University. [Online] Available: https://dropoutprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/paquetteryanwebquest_20091110.pdf [ Links ]

Phillips, D. & Adams, G. 2016. Child care and our youngest children. Caring for Infants and Toddlers, 11(1): 35-51. [ Links ]

Pilarz, A. R. & Hill, H. D. 2014. Unstable and multiple child care arrangements and young children's behavior. National Institute of Health: Public Access Author Manuscript, 29(4): 471- 483. [ Links ]

Pilarz, A. R., Sandstrom, H. & Henly, J. R. 2022. Making sense of childcare instability among families with low incomes: (Un)desired and (un)planned reasons for changing childcare arrangements. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 8(5): 120-142. [ Links ]

Sherr, L., Macedo, A., Tomlinson, M. & Cluver, L. D. 2017. Could cash and good parenting affect child cognitive development? A cross-sectional study in South Africa and Malawi. BMC Pediatrics, 17(123): 1-11. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2019. Mid-year Population Estimates 2019. Pretoria, RSA: StatsSA. [Online] Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/MYPE%202019%20Presentation_final_ for%20SG%2026_07%20static%20Pop_1.pdf [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2021. National Poverty Lines. Statistical Release no P0310.1. Pretoria: RSA: StatsSA. [Online] Available: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03101/P031012021.pdf [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2023. General Household Survey 2021. Pretoria, RSA: StatsSA. [Online] Available: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182021.pdf [ Links ]

Zembe-Mkabile, W., Surrender, R., Sanders, D., Jackson, D. & Doherty, T. 2015. The experience of cash transfers in alleviating childhood poverty in South Africa: Mothers' experience of the child support grant. Global Public Health, 10(7): 834-851. [ Links ]

Article received: 22/11/2022

Article accepted: 19/08/2023

Article published: 26/03/2024

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Babalwa Tyabashe-Phume is a Postdoc fellow at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Her research interests include childcare, mental health, disability rights and advocacy. The article resulted from her master's degree, conducted from February 2017 to December 2019. She conceptualised the study, conducted fieldwork, interpreted findings, wrote and revised the draft article.

Rina Swart is a professor in Dietetics and Nutrition at the University of the Western Cape. Her area of specialisation is in Public Health Nutrition with a focus on the prevention of all forms of malnutrition through nutrition policies and programmes as well as the evaluation of such policies and programmes. She serves as the Nutrition programme lead in the DSI/NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security. Swart supervised the study from 2017 to 2019, assisted with the interpretation of the study data and reviewed the final article.

Wanga Zembe-Mkabile is a Senior Specialist Scientist in the Health Systems Research Unit, at the South African Medical Research Council. Her research focuses on social determinants of health and social policy in the areas of maternal and child health, poverty and inequality. Zembe-Mkabile co-supervised the study from 2017 to 2019, and assisted with the interpretation of the study data and mentoring in the writing of the draft article and subsequent revisions.