Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

versión On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versión impresa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.60 no.1 Stellenbosch 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/60-1-1250

ARTICLES

The experiences of youths who left child and youth care centres of the Ekurhuleni Metro Municipality during the Covid-19 pandemic

Fadzaishe Bridget ZingweI; Maditobane Robert LekganyaneII

ISocial Worker, El- Shammah Home CYCC, Germiston, South Africa https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7712-0021 fmasimira@yahoo.co.uk

IIUniversity of South Africa, Department of Social Work, Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8434-7885 lekgamr@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Leaving a familiar environment can be daunting. Although previous studies investigated the experiences of youths who left care centres, few considered those who left during the Covid-19 pandemic. For this exploratory qualitative research study, we purposively recruited 12 African youths aged between 18 and 23, with least two years' experience of life in the care centres of Ekurhuleni Metro Municipality to investigate their experiences when they left such centres during the Covid-19 pandemic. The data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews, analysed according to Akinyonde and Khan's thematic analysis method, and verified using Guba and Lincoln's strategies. The findings revealed experiences that were clustered into three themes: preparing to leave, reflecting on life at the centre, and transiting from care during Covid-19. The recommendations proposed include the need to facilitate exit strategies for these youths, clear follow-up plans to support them, and collaboration of practitioners in the field of child and youth care.

Keywords: child and youth care centre; Covid-19; experiences; social work; youths

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Child and youth care centres (hereinafter care centres) can be traced as far back as the 18th- and 19th-century North American institutional homes, camps and clubs that emerged after the industrial revolution (Freeman, 2013). Although child and youth care work has existed for some time in South Africa, it was considered ancillary to other helping professions until recently, when it became professionalised (Allsopp, 2020). Section 191(1) of the Children's Act No 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006) defined a child and youth care centre as a facility providing residential care to more than six children outside their family environment. The reasons for placing children and youth in care centres include the need to remove them from their families because of unfavourable living conditions such as abuse, neglect, and abandonment (Mamelani Projects, 2015). In some instances, youths get placed in care centres as a consequence of behavioural issues resulting in volatile relationships in their families. In such cases, they are placed in care centres with the hope of 'reforming' their behaviour so that they can have healthy relationships. Most youths in care centres remain there until the age of majority, which is commonly the age of 18 (Glynn, 2021). However, section 176(2) of the South African Children's Act No 38 of 2005 allows them to remain in care until the age of 21 on two conditions: (1) their caregiver is willing and able to provide care; and (2) remaining in care is essential for them to complete their education or training (RSA, 2006).

Being placed in care centres has certain advantages for the youths, including having a roof over their heads, clothing, food and access to education. Care centres strive to enable the children and youths who live there experience a sense of home with adults on whom they can rely for guidance (Malatji & Dube, 2017). One can only imagine the difficulties of these youths when the time comes for them to leave the care centre as they prepare to forge their independence. Transitioning from a care centre where they had all the support needed into an environment where they must now fend for themselves might not be an easy experience for some.

For a successful reintegration into society, youths should be prepared to exit care centres whilst they are still in such centres through a gradual and supervised process determining where they will live, guiding them to develop the necessary life, financial management and job skills, and ensuring the necessary support (Better Care Network, 2023; Connelly & Saater, 2016). Mamelani Projects, for example, has a Transitional Support Programme for promoting youth independence (Mamelani Projects, 2015). For those who are to be reunified with their families, it is crucial to allow regular visits and communication by such family members and to assess whether problems that triggered the separation from families have been resolved and if it is in their best interests to return home (Better Care Network, 2023). Preparation support for youths leaving care centres varies per institution. In some instances it is determined by available resources. Institutions such as the SOS Children's Villages, for example, have good mechanisms and resources for preparing youths leaving their care, which most care centres do not have. This suggests that some of these children leave without being adequately prepared (Sekibo, 2020).

Most youths leaving care centres experience numerous challenges such as transitioning from dependence to independence (Glynn, 2021). They have to navigate a series of difficulties, including low educational attainment, homelessness, substance abuse, unemployment, conflicts with the law, unplanned pregnancies and mental health issues (Mamelani Projects, 2015; Sekibo, 2020). They often experience a lack of basic life skills or support networks, and become stigmatised for having been in a care centre (Pryce et al., 2016). A United Kingdom study among youths who left care for instance, found that they were stigmatised for having been in a care centre (Baker, 2017). In South Africa youths who have left care centres are exposed to crime, poverty, violence and high youth unemployment rates; many are not in education or training programmes (Bond, 2018). These challenges further complicate their transition when they return to communities that are riddled with difficulties (Mamelani Projects, 2015).

Youths who leave these centres after attaining the age of 18 are more vulnerable because of a lack of support compared to those who have more stable conditions by being reunited with their families (Glynn, 2021). They often lack the maturity required to manage emotional and psychological challenges stemming from unresolved childhood trauma such as neglect and abuse (Moodley, Raniga & Sewpaul, 2018). The realities of their independence are not what they envisaged and this could lead to uncertainty about their future (Baker, 2017). A UK study of youths who left care revealed that they faced disrupted school experiences as well as major life changes by becoming parents (Baker, 2017). In some instances, they are lonely and depressed due to lack of suitable living arrangements and have to deal with an abrupt loss of a support network (Atkinson & Hyde, 2019).

Despite these challenges, some youths were excited and looked forward to the independence that comes with adulthood. Unfortunately for those who left care centres during the Covid-19 pandemic, the experience was not as liberating as they had anticipated. Their vulnerability was greater than that of their peers, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, when regulations restricted their movements and negatively affected their daily lives, particularly regarding family relationships and life plans (Jindal, Suryawanshi & Kumar, 2021; Kelly, Walsh, Pinkerton & Toal, 2020). Instead of beginning their independence by searching for employment opportunities, some of these youths were forced to remain indoors, while companies that could have been their potential employers were either shutting down or downsizing. A study across eleven Asian countries on SOS Children's Villages found that youths who had exited care centres and who were on the verge of becoming self-sufficient returned to the SOS programme because of the impact of Covid-19 (Jindal et al., 2021). Those who are usually employed in the hospitality, entertainment, beauty and wellness sectors were severely affected by the slowdown of economic activities worldwide (Jindal et.al., 2021), and their hopes were either dashed or dampened by this new reality for which nobody was prepared.

Against this background, the researchers conducted a study in 2022 to investigate the experiences of youths who had left care during the Covid-19 pandemic. A preliminary literature review indicted that there was limited knowledge on this subject, with most studies focusing on youths who left care centres having been conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE STUDY

The theoretical framework underpinning this study was William Bridges's transition model, which explains transition as a process experienced by individuals who go through change or transformation (Leybourne, 2016). The theory covers three stages of change: the ending or letting go, the neutral zone, and the new beginning (Leybourne, 2016). This model was relevant to the transition process experienced by participants leaving care centres during Covid-19.

The letting go stage involves the individual's likelihood of experiencing a range of different emotions as well as a sense of loss (Leybourne, 2016). Emotions such as anxiety, fear, anger, sadness, and happiness might be common among youths leaving care centres, because of the likelihood of separating from old, familiar environments and the acquisition of the identity of imminently being an independent youth. During this stage, comfort levels are reduced, and long-familiar aspects are removed (Leybourne, 2016). Youths who leave care centres are not guaranteed the dependable comforts that they used to enjoy such as clothing, meals, support and shelter. The Covid-19 pandemic compounded some of these uncertainties since the youths had to prepare for the likelihood of eventually letting go of how they lived before the pandemic and adjust to independence in the midst of a pandemic. It could also be expected that the youths would have been fearful and anxious about being infected with Covid-19 when preparing to leave care. Additionally, they would have been concerned about how the communities that they were returning to were managing the pandemic.

The neutral zone is characterised by transitioning between 'what was' and 'what will be' as well as uncertainties about the future (Leybourne, 2016). These uncertainties stem from the youths' changing circumstances which have the potential to affect the meeting of their material needs and a loss of the recognition experienced whilst in a care centre, where they were treated like family (Glynn, 2021). It is normal for youths to experience confusion because of the challenges of independence after having depended on care centres for most of their lives. They are confronted with difficult decisions regarding where they are headed to next after exiting the care centre (Leybourne, 2016). Uncertainties among these youths are common, particularly regarding being reintegrated into the communities after being in a care centre and as well as the abilities to manage their lives away from the care centre. Covid-19 added to this uncertainty because during the pandemic these youths, like any person, did not know when life would return to normal.

The new beginning is launched when individuals begin to perform new roles during their transition. They are integrated into a new and different identity from the one they had at the care centre (Glynn, 2021). The youths are now considered to be young independent adults who can fend for themselves. They have taken on new roles as employees, or they have enrolled as students in tertiary institutions. But the pandemic could still negatively affect their independence through loss of employment or study opportunities, as well as the fear of Covid-19 infection.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study adopted an exploratory qualitative research design. Qualitative research is based on the fundamental idea that reality is subjective, and that people have diverse views and experiences regarding their environments (Anas & Ishaq, 2022; Cropley, 2022). It seeks to understand people's beliefs, experiences, attitudes, behaviours and relationships by generating non-numerical data (Anas & Ishaq, 2022). Through qualitative research, the researchers sought to understand how participants individually experienced transitioning from care centres to independence during Covid-19. The researchers also anticipated creating a platform for participants to freely explain their experiences and explore their views. In recruiting potential participants, a purposive sampling technique was used. As this approach seeks "information-rich" sources (Lapan, Quartaroli & Riemer, 2012), the participants were selected based on their potential to make a contribution to the study. Implementation of purposive sampling was guided by predetermined inclusion criteria. Participants had to:

• Be between 18 and 23 years of age;

• Already have been placed at a care centre before the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic and left during the pandemic;

• Have been placed in the care centre within the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality;

• Have left care because of a lapsed court order in terms of section 175 of the Children's Act 38 of 2005 Covid-19;

• Have discharged themselves from the care centre during Covid-19;

• Have been in care for at least two years prior to their departure from the care centres.

The participants were recruited by contacting the relevant authorities of the care centres where they had been placed. A formal request for permission to conduct the study was made by explaining the purpose, risks and benefits of the study as well as a request that the authorities seek permission from the participants to consent to their contact details to be shared with the researchers. Upon getting permission and the relevant consent, the participants were contacted, informed about the study and prepared for data collection. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews supported by an interview guide. The interview guide contained nine topical questions and seven biographical questions such as the duration of their stay in the care centre, their current place of residence, their experiences in a care centre and their experiences when transiting from care centres during the Covid-19 pandemic. Upon indicating their language preference for the interview, participants were then individually interviewed for approximately one hour.

Akinyode and Khan's (2018) thematic analysis strategy was used in analysing the data. This strategy involves five stages: (1) Data logging: transcribing the interviews verbatim; (2) Anecdotes: summarising the storylines in sequence; (3) Vignettes: narratively describing events as recounted by the participants; (4) Coding: reducing data into meaningful segments and assigning labels to different categories; and (5) Thematic network: closely examining data to develop themes. This strategy was deemed appropriate because it allowed researchers to immerse themselves in the data during each stage of analysis to identify themes and sub-themes.

Trustworthiness was ensured through tests for credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability (Anney, 2014; Stahl & King, 2020). Credibility was ensured by triangulating of multiple sources of data (youths from diverse care centres) and literature sources from diverse disciplines (Anney, 2014). Dependability refers to the consistency and reliability of the research findings, which entailed providing a detailed description of the process followed including the methodological approach (Moon et al., 2016). Elmusharaf (2012) defines confirmability as the degree to which the findings are the product of the focus of inquiry and not the researcher's biases. For confirmability, thick descriptions (including presenting findings verbatim) were provided (Anney, 2014; Elmusharaf, 2012). Transferability involves generalisability of findings to other samples from the same population (Lune & Berg 2017). Purposive sampling and thick descriptions were intended to enhance transferability (Anney, 2014; Elmusharaf, 2012; Moon et al. 2016).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical clearance for this study was sought from the University of South Africa's College of Human Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee (REF #: 48087688_CREC_CHS_2021), prior to data collection in 2022. This study was conducted in good faith and characterised by deliberate intentions by researchers to avoid any form of harm to the participants. It specifically maintained informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity, beneficence, data protection and debriefing (Akaranga & Makau, 2016; Arifin, 2018). All participants signed informed consent forms to confirm their voluntary participation in the study (Akaranga & Makau, 2016; Arifin, 2018). For confidentiality and anonymity, codes were used instead of participants' actual names. Section 12(2)(f) of the Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013, provides that if personal information is not obtained directly from participants, researchers should show why it was not reasonably practical to do so (RSA, 2013). It was impossible for researchers to directly collect personal information such as the names and contact details of these youths, because they did not even know them in the first place. They could only access them through a third party (officials from the care centres) who knew them because they had their records. The Act further provides in section 12(2)(c) and (d)(v) that if personal information is to be collected from a third party, researchers should show that it would not prejudice the legitimate interests of the participants and that such collection would take place only if necessary to maintain the legitimate interests of the participants or such a third party (RSA, 2013). This study sought to promote the legitimate interests of both the participants and the third party (the care centres) because it afforded participants an opportunity to record their challenges in order to draw the attention of potential parties who may wish to support them. The findings will specifically provide social workers and other practitioners involved in child and youth care with the information to guide the necessary support interventions for the benefit of these youths and the care centres.

THE RESEARCH FINDINGS

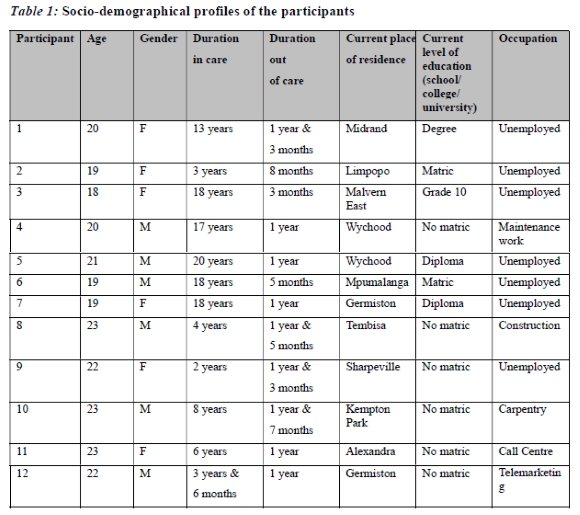

The overall findings were related to the research questions, goal and objectives of the study. Table 1 below depicts the socio-demographical profiles of the participants.

Twelve participants (six males and six females) were interviewed, of whom eight were in their mid-twenties, and four in their late teens. Six participants had spent between thirteen and twenty years in care centres, and the other six had spent between two and eight years. Of the twelve participants, two moved to Mpumalanga and Limpopo, and ten remained in Gauteng after exiting care. Regarding the level of education, one participant was completing Grade Ten and two were completing Matric during the time of the interviews. A total of six participants had not been able to reach Matric, although they expressed an interest in doing so. The remaining three participants had managed to complete their Matric and were studying at a tertiary institution. All participants had formerly been placed at the care centres within the City of Ekurhuleni Municipality. Occupationally, only five participants were employed, including in carpentry, construction, maintenance, a call centre and in telemarketing.

FINDINGS: THEMES AND SUB-THEMES

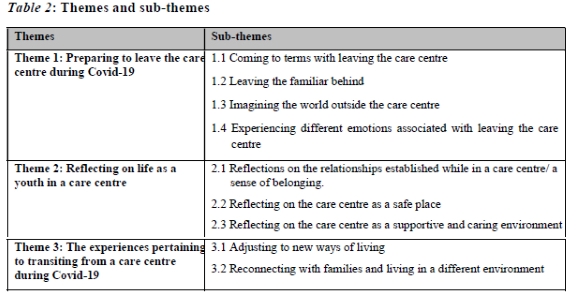

We asked participants about their experiences when they left a care centre during the Covid-19 pandemic. Their responses were analysed and clustered into themes and sub-themes as presented in Table 2.

As reflected in the Table, three themes which were further divided into eight sub-themes emerged from the data analysis. Each of these themes and their sub-themes is introduced and explained below.

Theme 1: Preparing to leave the care centre during Covid-19

The experiences associated with preparing to leave a care centre during Covid-19 was one of the themes emerging from the data. Under this theme, four sub-themes were identified: coming to terms with the reality of leaving the care centre; leaving the familiar behind; imagining the world outside the care centre; and, experiencing different emotions associated with leaving the care centre.

Sub-theme 1.1: Coming to terms with leaving the care centre

Coming to terms with the reality of leaving the care centre was one of the prominent experiences faced by the participants. Participant 1 was among those who expressed this:

It was stressful at first, but I got to adjust. I had to tell myself that this was the situation I was facing so I had to get used to it.

In responding to the question on the experiences associated with coming to terms with leaving the care centre, Participant 8 said,

It was very sad but unfortunately I had to leave because I had to face the outside.

Another participant who described their experiences was Participant 7, who said,

It struck me like, it's going to happen soon.

Participant 12 expressed his dissatisfaction regarding the sudden discharge:

It was like you'd be told that you're leaving on Monday. It wasn't so nice because most of us enjoyed our time there, especially when you were there for long ... now you were leaving behind the ones that you were close to and going somewhere else. I also had to quickly think about what to do and where to go.

The responses from the participants indicate that it was a difficult experience for them as they had to come to terms with leaving the care centre. Participant 7's response, for instance, hinted at a sudden awakening that she had in the time leading up to her departure from the care centre. These responses mirrored Amechi's (2020) observation that youths leaving care centres are often thrust into adulthood without adequate preparation, which can be especially detrimental during a pandemic. Trapenciere (2018) considers exiting care centres as one of the most important processes for these youths, because this transition into adulthood is characterised by having to adopt new roles and responsibilities such as finding employment, parenthood and paying bills. A study by Stein (2014) revealed that many youths leaving care were unprepared and uninformed about the next step in their lives until they were about to leave; consequently they were ill-equipped to cope with the transition into independence. In terms of the Bridges Transition Model, it can be understood that coming to terms with leaving care is the beginning of letting go. In this instance, the participants were letting go of their lives at care centres and preparing themselves for new lives upon their exit. It is generally a difficult and inevitable transition for the youths concerned.

Sub-theme 1.2: Leaving the familiar behind

As alluded to by the participants, leaving the care centres was an uncomfortable experience for them, because they were leaving behind places and people that were familiar to them.

Participant 2 was among those who expressed such concerns:

... I was going to leave everybody behind that I had known for a long time, and I was going to a place where I had no friends. The house mothers were there for me when I needed someone to be there for me. Most of the girls were like my sisters.

Participant 7 described how preparing to leave care centres was characterised by thoughts of her uncertain future:

I was at the centre practically for my whole life and just the thought that the time was drawing close for me to leave was a lot to take in. Whenever I thought about it, I would start to imagine what life would be like once I left the centre. It was just a lot to think about.

Leaving the familiar care centre and venturing into an uncertain world was also an experience reported by Participant 3:

For me it was coming to the realisation that the centre would no longer provide for me the way that they did when I was there. That was hard.

By spending most of their lives at the care centres, the youths experienced a sense of comfort, resulting in some difficulties when the time came to leave their familiar environment and its people. Participants became anxious about their uncertain future after leaving the care centre. What they were going through is reflected in the neutral zone of the Transition Model, characterised by uncertainty resulting from changing circumstances (Leybourne 2016). They were worried about leaving the people with whom they had established and maintained relationships as well as moving from the general environment in these centres. Yet the relationships that the youths built in care were essential for their future growth and development (Haggman-Laitila, Salokekkila & Karki, 2019).

In the neutral zone of their transition, the participants were aware that change was imminent, and they wondered how they would get used to life outside the centre. Some were not yet comfortable with the idea of adapting to a new way of life, as reflected in Participant 3's response. When youths are in care centres, they engage in material and psychosocial exchanges with their social network often represented by these centres. They have relationships of dependence that they utilise to meet their basic needs such as accommodation and food (Glynn, 2021). This often resulted in what Trapenciere (2018) refers to as a problem of 'consumerism' among the youths at care centres, because everything is provided for them. However, the reality that these relationships and their benefits were inevitably bound to end, also created a sense of loss for youths leaving care. This is to be expected during the normal transitional process of the letting go stage of the Transition Model. Focusing on preparing to leave the care centre reminded participants of the impending losses they were about to experience in terms of relationships, familiarity and security (Dallas-Childs & Henderson, 2020).

Sub-theme 1.3: Imagining the world outside the care centre

Besides preparing to leave these care centres, it also emerged that participants were already beginning to visualise their lives outside the care centres.

Participant 2 was particularly wondering about how people were coping in the context of Covid-19:

just wondered how people out there were surviving during Covid-19 because we would hear about many people losing their jobs ...

As with Participant 2 above, Participant 7 also shared sentiments pertaining to people coping with Covid-19:

I wondered how people were handling the virus out there.

Participant 5 had this to say:

I knew that I would have independence and see the world, like how it is out there ... When you are at the centre, you don't really go anywhere much except for school. I knew things would be different because I would get to see more places and meet new people.

The participants' narratives regarding life outside the care centre revolved around their preparation to leave through imagining how their lives would be like outside the centre. This included placing themselves in their communities through imaginations. Their narratives are not surprising in the light of an observation by Trapenciere (2018), that youths from care centres may have problems with adapting to society because of negative views about their residence there. Moodley et al. (2020) cite several studies demonstrating that youths spoke about their care centre as being a separate world from the community, which is an indication of the disconnection of care centres from the broader communities. This is not surprising, because of the minimal interaction between the care centre and the community (Moodley et al., 2020). It is important to note that not all youths in care centres have families who visit them, as they were abandoned in the first place. Those who have families may also have strained relationships resulting in poor communication that intensifies during this disconnect. Moodley et al. (2020) found in a South African study of youth transitioning out of care that, as with the participants of this study, some youths wondered whether everyone else was adhering to the measures in place to prevent the spread of Covid-19 infections, just as they were themselves confined in the centre. In another study among American youths in residential care, participants acknowledged that a ban on visits during the pandemic assisted in minimising their risk of contracting Covid-19 because no one would know if the visitors had contracted the virus (Howey, Assadollahi & Lundahl, 2022). The participants in this study indicated that as far as social distancing during Covid-19 was concerned, they felt that there was a divide between their world at the care centre and the one that they were entering (Howey et al., 2022). Another South African study by Haffejee and Levine (2020) at a Gauteng care centre investigated the views of youths about the pandemic and revealed that youths had an awareness of how Covid-19 impacted on them, their families and the communities to which they would be returning (Haffejee & Levine, 2020).

The thoughts that the participants had about life when they exited the care centre emerged in the neutral zone of Bridges Transition Model, which is the most disconcerting phase of the transition (Lucidity, 2023). Emotions such as fear and anxiety, which are common to the letting go stage of the Transition Model, were also displayed by participants who were concerned about Covid-19 virus, which was spread through human contact and therefore required every individual to take care of not only themselves, but of others.

Sub-theme 1.4: Experiencing different emotions associated with leaving the care centre

As the time of departure came closer, participants experienced various emotions associated with the reality of knowing that they were leaving the care centres. These emotions included the fear of being infected with Covid-19 once they had left the care centres. Some were anxious and worried and were not happy because they were leaving.

Participant 5 shared her anxiety regarding Covid-19 by saying,

I was anxious because I was leaving during Covid-19. We heard about how hard life was since people started getting infected. We heard about how people lost jobs and got sick, so it sounded like life was a lot more difficult out there.

In the interview, Participant 6, revealed his worries about the possibility of being infected with Covid-19:

I was also worried about getting infected because I was going to move to another province to live with my grandmother, my aunt and my brother so I didn't know how that was going to be.

Participant 11 also conveyed her fears and worries about leaving the care centre during the pandemic:

I was afraid and worried. I was going to leave the centre during Covid-19 and there were many people getting sick and dying during this time. At the centre we did not go out since Covid-19 started and there was hard lockdown. That made us a bit more safe because we didn't move around.

Participant 4's main concern was fear of infection:

The issue of Covid-19 was scary because others were sick during the time that I was preparing to leave the centre. I was scared of being infected and being sick.

The narratives of the participants reflected what transpires in the ending stage of Bridges Transition Model, where a person is likely to have to deal with different emotions such as anger, anxiety and sadness (Leybourne, 2016). Although reported emotions such as worry and fear are not uncommon at this stage of the Bridges Transition Model, they were intensified when the participants had to leave their care centre during the pandemic. The ending stage is described by Lucidity (2023) as an important emotional stage during which one accepts the ending of a phase of life and understands how to manage the transition into the next phase. The participants' emotional reactions show that they understood that what they were comfortable with is about to be replaced by something new (Lucidity, 2023). Baker (2017) asserts that in several studies youths leaving care centres report feeling anxious and stressed by their departure. This notion is confirmed by previous research studies which show that youths who leave care centres are a marginalised group for whom transitioning from care became even more difficult and worrisome during the Covid-19 pandemic (Modi & Kalra, 2022). Kelly, Walsh, Pinkerton and Toal (2021) indicated how youths who left care during Covid-19 were uncertain about their future as they feared for their health. Ofsted (2022) investigated the views of youths leaving care centres and found many of them to be worried about the area that they were going to live in, or people whom they were going to live with. This response was also revealed by the emotional responses of the participants in this study.

Theme 2: Reflecting on life as a youth in a care centre

In order to fully understand the participants' experiences, it was essential do so from a broader perspective including considering the quality of their lives at the care centres. This theme generated the three sub-themes explained below.

Sub-theme 2.1: Reflections on the relationships established while in a care centre - a sense of belonging

The responses of the participants regarding the nature of their relationships in the care centre led to a sub-theme around their experiences of a sense of belonging. The care centre was a place where participants felt loved and accepted.

This was demonstrated during Participant 12's interview:

When I was there, I was well-connected with everyone. I had two friends that I enjoyed spending time with.

Participant 1 shared similar sentiments:

I came to the centre at a young age, and so because I grew up around the adults and kids at the centre, I became so comfortable around them and felt like I belonged somewhere. I felt that they cared about me.

In the case of Participant 2, she felt other girls at the care centre were more like sisters to her:

Most of the girls were like my sisters. I would help the younger girls with their homework when they came to me to ask for help.

A sense of belonging as explained by the participants seems to have emanated from the care and support they received from the care centre. According to Dallas-Childs and Henderson (2020), belonging and feeling at home are closely linked to a sense of security and positive identity for youths in care centres. Kovacevic and Vujovic (2015) also note that youths who leave care centres tend to be protected, safe and have established close relationships with at least one adult at the care centre. Negard, Ulvik and Oterholm (2020) also attest that youths who have been placed in care centres report a sense of belonging. A South African study by Nurcombe-Thorne, Nadesan and van Breda (2018) found that a sense of belonging and close relationships play a crucial role in identity development among children in care. Lukšik and Hargašová's (2018) Slovakian study of the impact of residential care on the quality of life for youths when they leave care revealed that those who maintained supportive relationships with staff and other youths from care centres had a continued sense of belonging and emotional stability. These findings echo the sentiments of the participants of this study, who also felt a sense of belonging emanating from the good relationships that they had established with the centre's staff and other youths at the care centre.

Sub-theme 2.2: Reflecting on the care centre as a safe place

The safety that the participants referred to through this sub-theme is twofold: (1) safety of feeling protected by people who care about them, and (2) safety from Covid-19 infections.

One of the participants who reflected on the care centre as being a safe place was Participant 5:

It was a really safe place for me. If you were not comfortable with something, they wouldn't force you to do it. They respected that you are a person, and they made you feel that you could make your own choices.

Participant 1 had this to say regarding safety at the centre:

... even though it was a space where we all had our own problems, it became a family that I always wanted. It became my safe place. I could be myself when I was there. I had people to go to when I needed help. I felt protected.

For Participant 11 and Participant 8, their feelings of safety were related to being protected from Covid-19 infections. Participant 11 had this to say,

I felt safer at the centre. I worried that when I went back home, the situation would not be the same. I would ask my sister over the phone how people were behaving during this time, and she said that some people were moving around without masks, and they were not practising social distancing.

In sharing his experiences regarding safety from Covid-19, Participant 8 said,

I did not know how it was going to be. I hoped that it would be safe. At the centre, we had to follow strict rules in order to be safe, and we didn't really go anywhere during lockdown, so we were not around many people. I was going back home to Tembisa, and there are a lot of people who live there.

A sense of safety is of paramount importance for youths in care centres considering that they would have experienced hardships prior to being placed there (Sellers et al., 2020). Sellers et al. (2020) observed that the relationships formed between the adults and youths in care centres created a foundation of safety among these youths. For Dallas-Childs and Henderson (2020), the feeling of safety experienced by these youth is linked to their sense of belonging. Participants of this study felt safe at their care centres, because they knew that they had people whom they could rely on and turn to for support. Participant 5 and Participant 1 explained how they were not obliged to participate in activities and were given the freedom to be themselves, which in turn enabled a sense of safety. Participant 11 and Participant 8 spoke about safety in the context of being protected from Covid-19 infections. Their responses regarding feeling safe at the care centres during Covid-19 support findings in other studies. Haffejee and Levine (2020) studied thirty-two youths at a care centre in Gauteng and found a range of emotions including a sense of safety they experienced when they were in care. The same study also found that this sense of safety enabled the youths to cope during Covid-19 because of the support offered by the care centre (Haffejee & Levine, 2020).

Sub-theme 2.3: Reflecting on the care centre as a supportive and caring environment

When reflecting on their experiences while at the care centre, participants said it was generally a supportive and caring environment. When describing the experiences of support and care that she had received at the centre, Participant 9 said,

There was food, and they gave us clothes. When my sister and I lived with our previous foster mother, we would go to bed hungry sometimes. She would make us sleep on the floor, and we would be cold. At the centre, each one of us had a bed and warm blankets so I could have a good sleep.

Participant 10 shared similar sentiments:

Accommodation and food were provided at the centre. They also bought us clothes. All that was available at the centre, so we didn't have to worry about that.

Participant 8 appreciated support provided for his educational needs:

... when I came to the centre, I didn't know how to read; they taught me how to read ... It makes me feel so happy and thankful because if they didn't teach me, I would not be able to do many things that involve reading and writing.

The needs of the participants that were met by the care centres covered all areas of their lives, from food to educational support. Mendes (2022) notes that youths in care centres enjoy a stable environment where they are provided with housing, food, clothing and education. Agere (2014) reported that youths who leave care centres benefit from access to safe accommodation, security, psychosocial support, and social work services. However, Modi and Kalra (2022) found that transitioning from protective care centres, where there is support, to independence often creates a plethora of difficulties for these youths. An important aspect to note is that most children and youths in care centres come from highly disadvantaged families and backgrounds that are characterised by poverty, amongst other factors (Campo & Commerford, 2016) and it is therefore not surprising that they highlighted care and support as important parts of the reflections on their life at the care centre. In support of this viewpoint, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2020), reported that youths who left care centres during the pandemic often returned to impoverished households which were already living below the poverty line before the pandemic, which substantiates their expressions of appreciating the support and care received at the care centre.

Participants also wondered whether they would be able to support themselves after depending on care centres for a long period. The letting go stage of the Transition Model best describes the state of the participants when they were positioned for transition, which was at a point where they had to forfeit services from the care centres. Participants had to accept that they would not receive the same support that they had while they were still at the care centre. Participant 10 spoke about how he did not have to worry about accommodation, food and clothes, because they were provided for him at the care centre. At this stage of the transition process, they had to let go of these provisions and figure out how they would begin to manage these processes including providing for themselves once they exited care.

Theme 3: The experiences pertaining to transiting from a care centre during Covid-19

The two sub-themes regarding participants' adjusting to new ways of living and reconnecting with their families were derived from the theme ' The experiences pertaining to transiting from care centres during Covid-19' and they are discussed below.

Sub-theme 3.1: Adjusting to new ways of living

As reported by the participants, leaving the care centre and starting a new life required some adjustment. They explained the necessary adjustments that they had to make.

Participant 10 had this to say:

I had to get used to living at a place where there was no adult supervision like at the centre. I was forced to grow up. I had no choice but to be responsible and save money for myself. No one was buying me clothes like what used to happen at the centre. No one would follow up after me or remind me to do things.

In Participant 5's words:

The thought of where we would be after Covid-19 [and] if we would wear masks for the rest of our lives. You had to be careful of where you went and who you came into contact with. I couldn't go anywhere to buy things like airtime to communicate with my friends, so communication was also very difficult. My sponsor family had to stock up on food. When they came back from the shops, we had to sanitise the bags first before and after packing the groceries. It was just not easy to get used to living this kind of way.

When alluding to such adjustments, Participant 2 said,

I am preparing for my Matric rewrite so that disturbed me a lot. Adjusting to a new environment and at the same time having to study. I need data all the time too and that requires money. Our house does not have electricity.

Participant 1 also shared a similar experience:

When the pandemic began, I had just started school and we had to have data. She explained, Online studying wasn't as easy as it is with one-on-one where you can see the teacher. I had challenges with studying online but then I kind of got the hang of it.

Confusion is a feature of the neutral zone of the Bridges Transition Model and it appears to be common among youths who leave care centres as they face the uncertainties regarding their future. It was particularly felt by those who left during the Covid-19 pandemic, which amplified their confusion by upsetting their normal ways of living. In their Covid-19 response plan for the child sector in South Africa, the Department of Social Development (DSD, 2020) was concerned that maintaining social distance and always wearing a mask would be difficult for the country's youths. It was hard to adjust to these new norms, as confirmed by the participants, including Participant 5. Participant 1 and 2 specifically reported that they experienced challenges in their education as they had to attend classes online. Their experiences reflected some of the findings of the International Labour Organization (ILO, 2020) study which found that globally education and training institutions had closed their doors to students because of the pandemic and switched to alternative learning opportunities such as virtual learning, making it necessary for teaching and learning to take place predominantly on digital platforms. Kelly et al. (2021) note that a shift in social and professional interactions from physical to online modes of engagement negatively affected youths leaving care, because most have limited financial resources to fund online activities and this resulted in the 'digital divide'. Although reports point to some youths leaving care being able to adjust to virtual modes of education delivery (Munro et al., 2021), others such as Participant 1 spoke about missing the face-to-face interactions with teachers and peers.

Sub-theme 3.2: Reconnecting with families and living in a different environment

Reconnecting with family and living in a family environment that is different from that of the care centre was one of the challenges reported by participants. The following extracts highlight such experiences.

In Participant 6's view, something positive came out of Covid-19:

Covid-19 actually helped me to get close to my family and reconnect with them because we spent a lot of time together. My aunt on the other hand works a lot harder to provide for us. She said when Covid-19 started she lost a lot of opportunities to work because of lockdown.

Regarding his experience Participant 12 said,

I went to live in Germiston with my father and brother. At first it was weird because I never thought that I would get that opportunity but currently things are good. In the past we used to fight and all of that, but now it's not like before.

Participant 9 explained:

It was the first time for me to live with my brother in the same house since we were very young. I was happy to live with my brother because we had lived apart for many years. It gave us some time to get to know each other better. My brother was not going to work during the hard lockdown, so we spent a lot of time together.

In response to the question, Participant 11 said,

I was able to spend time with my family after a few years of being at the centre. It was different this time because I was not causing problems like I used to do before. I was getting close to my sister and her baby, my niece. It's nice to be an aunty.

The participants' narratives reflect some components of the Bridges Transition Model, particularly the new beginning in which individuals invest their energies in the new course of their lives. In other words, during this stage, the youths begin to concentrate on their new lives after leaving the care centre. In this study, participants worked on re-establishing relationships that had been problematic in the past and which might have been a contributing factor to their placement in the care centre. Participant 6 and Participant 12, for example, said they reconnected with family and strengthened these relationships because the Covid-19 lockdowns forced people to remain in the same spaces for long periods of time. Campo and Commerford (2016) report that whilst reaching the age of 18 is a time for independence and exploration, family relationships are still vital during this period. Participant 11, who had a strained relationship with her family, had started working on their relationship and found it important to prove to them she has changed. Earlier literature confirms these participants' experiences in that reconnecting with parents or extended families after leaving care can potentially be used as an opportunity to renegotiate past relationships and reconcile differences (Baker, 2017). In support of Baker's (2017) affirmation, Sting and Groinig (2020) state that the future linkage to their birth family may be translated as being a promise of support when youth leave care centres, and it is also associated with the hope that the relationship with their family can improve. Participant 9, who did not have an opportunity to bond with her brother because they were raised in different households, began to do so because of the Covid-19 restrictions.

DISCUSSION

As revealed by the study, youths have to cope with a range of experiences when they leave care centres. Firstly, they must be properly prepared to leave, which when viewed from the perspective of the Bridges Transition Model, is embodied by an acceptance of the end of their life at the care centre and the preparation for a new beginning (Leybourne, 2016). For the participants of this study, preparation to leave the care centre involved coming to terms with the fact that their time to leave had eventually come, and the realisation that when they leave, they were leaving a familiar environment. As the time for leaving drew closer, some took their preparations even further by visualising themselves living a life outside of the care centre. As a result, they started to experience various emotions such as anxiety, worry and fear, which were associated with their imagining life after leaving care. Such emotions were also previously reported in a study of the impact of Covid-19 on childhood by Hartford and Fricker (2020), who found that the spread of Covid-19 and the related restrictions led to extreme anxiety and fear of being infected with Covid-19, and of possibly infecting members of their families.

Secondly, participants' experiences of leaving care centres included reflecting on their own lives, with the care centre being a familiar, supportive, caring and safe environment, as well as reflections on the loss of relationships which they had built up over years. Loss of support is not an uncommon experience for youths who leave care centres; it is a normal experience, even though it makes their transition from care difficult (Okland & Oterholm, 2022). According to Tanur (2012), youths are particularly prone to losing the social, economic and emotional support that they had become accustomed to at the care centre after transitioning to independence.

Thirdly, despite being a challenge to youths who left care centres during the pandemic, Covid-19 brought benefits for some, who found in it, an opportunity to reunite with their family and work on improving their relationships with family members. This relationship-building opportunity was particularly enhanced by, among other factors, Covid-19 restrictions that compelled people to remain together indoors. This corroborated Sting and Groinig's (2020) findings that youths who exit care feel positively about improving their relationships with family members. The participants' experiences were mapped through all the three stages of the Bridges Transition Model, with the ending stage being evident through the emotional experiences they felt when leaving the familiar behind, which left some wondering about their future and in this way reflected the neutral zone of the model (Glynn, 2021 ; Leybourne, 2016). Commitment to work on previously compromised relationships and devising future plans signalled a new beginning, once participants began cultivating their new lives after departing from the care centres (Glynn, 2021; Leybourne, 2016).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study did not only highlight how negatively Covid-19 impacted on youths who left care during the pandemic, it also demonstrated the advantages of leaving care centres during Covid-19. It demonstrated the youths' difficulties of leaving the care centres because of their familiarity with these environments and the relationships that they had built. Although their experiences were characterised by fear, anxiety and uncertainty, they continued to find ways of adjusting to their new lives by working on assuring family members that their behaviour had improved. As they navigate through their new-found independence, these youths will need support and guidance; hence the following recommendations are offered:

• Social workers, child and youth care workers and other relevant professionals should work collaboratively to ensure the continuation of care and support for youths in their lives beyond the care centres.

• Exit programmes should be designed and implemented to ensure proper preparation of these youths before they leave the care centre.

• Social workers should mobilise the resources to assist youths after they exited the care centres, particularly to support them in furthering their education and enabling them to meet their basic needs.

• Longitudinal research studies are suggested to specifically ascertain the conditions and overall lives of youth after they have left the care centres.

REFERENCES

Agere, L. M. 2014. An evaluation of the role of child and youth care centres in the implementation of South Africa's Children's Act. Master's dissertation. University of Fort Hare, South Africa. [ Links ]

Akaranga, S. I. & Makau, B. K. 2016. Ethical considerations and their applications to research: A case of the University of Nairobi. Journal of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research, 3(12): 1-9. [ Links ]

Akinyode, B. F. & Khan, T. H. 2018. Step by step approach for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability, 5(3): 163-174. [ Links ]

Allsopp, J. M. 2020. Child and youth care work in the South African context: Towards a model of education and practice. Doctoral thesis. Durban University of Technology, South Africa. [ Links ]

Amechi, M. H. 2020. The forgotten students: Covid-19 response for youth and young adults aging out of foster care. [Online] Available: https://digitalcom.mons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1069&context=eflfac_pubs. [Accessed: 22/04/2023] [ Links ]

Anas, N. & Ishaq, K. 2022. Qualitative research methods in social and behavioural science research. International Journal of Management, Social Sciences, Peace, and Conflict Studies, 5(1): 89-93. [ Links ]

Anney, V. A. 2014. Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trends on Educational Research & Policy Studies, 5(2): 272-281. [ Links ]

Arifin, S. R. M. 2018. Ethical considerations in qualitative study. International Journal of Care Scholars, 1(2): 30-33. [ Links ]

Atkinson, C. & Hyde, R. 2019. Care leaver's views about transition: A literature review. Journal of Children's Services, 14(1): 42-58. [ Links ]

Baker, C. 2017. Care leavers views on their transition to adulthood: A rapid view of the evidence. Coram Voice: University of Bristol. [ Links ]

Better Care Network. 2023. Leaving alternative care and reintegration. [Online] Available: https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/principles-of-good-care-practices/leaving-alternative-care-and-reintegration. [Accessed: 19/06/2023]. [ Links ]

Bond, S. 2018. Care-leaving in South Africa: An international and social justice perspective. Journal of International and Comparative Policy, 34(1):76-90. [ Links ]

Campo, M. & Commerford, J. 2016. Supporting young people leaving out-of-home care. [Online] Available: https://aifs.gov.au/resources/policy-and-pactice-papers/supporting-young-people-leaving-out-of-home-care, [Accessed: 04/02/2023]. [ Links ]

Connelly, G. & Saater, I. 2016. Alternative childcare and deinstitutionalisation: A case study of Nigeria. Brussels: SOS Children's Village International. [ Links ]

Cropley, A. J. 2022. Introduction to qualitative research methods. A practice-oriented introduction for students of psychology and education. Bucharest: Editura Intaglio. [ Links ]

Dallas-Childs, R. & Henderson, D. 2020. Home and belonging: Mapping what matters when moving on. Scottish Journal of Residential Care, 19(2): 1-18. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development. 2020. Covid-19 childcare and protection sector response plan. [Online] Available: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Docs/exe_rq_na/18d2c837-c8b9-4657-8f82-5db3bb6b465c.pdf. [Accessed: 16/01/2023]. [ Links ]

Elmusharaf, K. 2012. Introduction to qualitative research: Training course in sexual and reproductive health research. Geneva: University of Medical Science and Technology. [ Links ]

Freeman, J. 2013. The field of child and youth care: Are we there yet? Child and Youth Care Services, 34(2): 100-111. [ Links ]

Glynn, N. 2021. Understanding care leavers as youth in society: A theoretical framework for studying the transition out of care. Children and Youth Services Review, 121(2021):1-12. [ Links ]

Haffejee, S. & Levine, D. T. 2020. 'When will I be free': Lessons from Covid-19 for child protection in South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(2): 1-14. [ Links ]

Haggman-Laitila, A., Salokekkila, P. & Karki, S. 2019. Young people's preparedness for adult life and coping after foster care: A systematic review of perceptions and experiences in the transition period. Child and Youth Care Forum, 48(1): 633-661. [ Links ]

Hartford, D. & Fricker, T. 2020. How Covid-19 is changing childhood in South Africa. Pretoria: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Howey, W., Assadollahi, A. & Lundahl, B. 2022. Group homes and Covid-19: Perspectives of youth residents, staff, and caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15): 8978. [ Links ]

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2020. Youth and Covid-19: Impacts on jobs, education, rights and mental well-being. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

Jindal, P. K., Suryawanshi, M. K. & Kumar, R. 2021. Preparing care leavers with short and long term intervention to face challenges of the pandemic of Covid-19 in Asia. Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 8(1):90-97. [ Links ]

Kelly, B., Walsh, C., Pinkerton, J. & Toal, A. 2020. Leaving care during Covid-19. Belfast: Queens University. [ Links ]

Kelly, B., Walsh, C., Pinkerton, J. & Toal, A. 2021. "I got into a very dark place": Addressing the needs of young people leaving care during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Children's Services, 16(4): 332-345. [ Links ]

Kovacevic, I. & Vujovic, I. 2015. It is hard when the door closes behind you, leaving institutional care: analysis of policies, institutional framework and practice. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Lapan, S. D., Quartaroli, M. T. & Riemer, F. J. 2012. Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [ Links ]

Leybourne, S. L. 2016. Emotionally sustainable change: Two frameworks to assist with transition. International Journal of Strategic Management, 7(1): 23-42. [ Links ]

Lucidity. 2023. Bridges Transition Model. [Online] Available: https://getlucidity.com/strategy-resources/bridges-transition-model. [Accessed: 17/04/2023]. [ Links ]

Lukšik, I. & Hargašová, L. 2018. Impact of residential care culture on quality of life of care leavers. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 9(2): 86-108. [ Links ]

Lune, H. & Berg, B. L. 2017. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 9th Edition. Essex: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Malatji, H. & Dube, N. 2017. Experiences and challenges related to residential care and the expression of cultural identity of adolescent boys at a Child and Youth Care Centre (CYCC) in Johannesburg. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(1): 109-126. [ Links ]

Mamelani Projects. 2015. Transitional support programmes for the child and youth care sector. Cape Town: Mamelani Projects. [ Links ]

Mendes, P. 2022. Homelessness is common for teens leaving out of home care. [Online] Available: https://www.theconversation.com/homelessness-is-common-for-teens-leaving-out-of-home-care-we-need-to-extend-care-until-they-are-at-least-21-181167. [Accessed: 01/01/2023]. [ Links ]

Modi, K. & Kalra, G. K. 2022. Assessing the impact of Covid-19 and the support provided to youth leaving care in India. Youth, 2(1): 53-66. [ Links ]

Moodley, R., Raniga, T. & Sewpaul, V. 2020. Youth transitioning out of residential care in South Africa: Toward ubuntu and interdependent living. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1): 45-53. [ Links ]

Moon, K., Brewer, T. D., Hartley, S. R., Adams, V. M. & Blackman, D. A. 2016. A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals. Ecology and Society, 21(3): 1-21. [ Links ]

Munro, E. R., Friel, S., Newlands, F., Baker, C., Garcia, A. & Lynch, A. 2021. Care leavers, Covid-19 and the transition from care (CCTC study): Research briefing one: Professional perspectives on supporting young people leaving care in the context of Covid-19. [Online] Available: https://www.beds.ac.uk/media/rxOfk4e3/cctc_research-briefingone_professional_perspectives_final2021pdf. [ Accessed: 12/08/2022]. [ Links ]

Negard, I. L., Ulvik, O. S. & Oterholm. I. 2020. You and me and all of us: The significance of belonging in a continual community of children in long-term care in Norway. Children and Youth Services Review, 118(4): 1-10. [ Links ]

Nurcombe-Thorne, A., Nadesan, V. S. & van Breda, A. D. 2018. Experiences of 'I' and 'we' among former looked- after children in South Africa. Child and Family Social Work, 23(4): 640-648. [ Links ]

Ofsted. 2022. 'Ready or not': Care leavers ' views of preparing to leave care. [Online] Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ready-or-not-care-leavers-views-of-preparing-to-leave-care/ready-or-not-care-leavers-views-of-preparing-to-leave-care. [Accessed: 09/04/2023]. [ Links ]

Okland, I. & Oterholm, I. 2022. Strengthening supportive networks for care leavers: A scoping review of social support interventions in child welfare services. Children and Youth Services Review, 138(6): 1-11. [ Links ]

Pryce, J. M., Jones, S. L., Wildman, A., Thomas, A., Okrzesik, K. & Kaufka-Walts, K. 2016. Aging out of care in Ethiopia: Challenges and implications facing orphans and vulnerable youth. Emerging Adulthood, 4(2): 119-130. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2006. Children's Act, 38 of 2005. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944. (19 June 2006). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2013. Protection of Personal Information Act, 4 of 2013. Government Gazette, Vol. 581, No. 37067. (26 November 2013). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Sekibo, B. 2020. Experiences of young people early in the transition from residential care in Lagos State, Nigeria. Emerging Adulthood, 8(1): 92-100. [ Links ]

Sellers, D. E., Smith, E. G., Izzo, C. V., McCabe, L. A. & Nunno, M. A. 2020. Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of adult relationships. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 37(2): 136-155. [ Links ]

Stahl, N. A. & King, J. R. 2020. Expanding approaches for research: understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Developmental Education, 44(1): 26-28. [ Links ]

Stein, M. 2014. Young people's transitions from care to adulthood in European and post-communist eastern European and central Asian societies. Australian Social Work, 67(1): 24-8. [ Links ]

Sting, S. & Groinig, M. 2020. Care leaver's perspectives on the family in the transition from out-of-home care to independent living. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 11(4.2): 140-159. [ Links ]

Tanur, C. 2012. Project Lungisela: Supporting young people leaving state care in South Africa. Child Care in Practice, 18(4): 325-340. [ Links ]

Trapenciere, I. 2018. Transition trajectories from youth institutional care to adulthood. [Online] Available: https://doi.org/10/051/shsconf/20185101002. [Accessed: 14/04/2023]. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2020. Covid-19 rapid emergency needs assessment for the most vulnerable groups. Pretoria: UNDP. [ Links ]

Article received: 01/05/2023

Article accepted: 09/07/2023

Article published: 26/03/2024

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Fadzaishe Bridget Zingwe was a Master of Social Work student at the University of South Africa and is currently a social worker at a child and youth care centre in Germiston, South Africa. Her interest is in child and youth care. This study was part of her Master's research which was conducted from April 2021 to November 2022. Her primary role in this project was to conceptualise it, collect and analyse the data and writing up of the manuscript.

Dr Robert Lekganyane is a senior Lecturer in the Department of Social work at the University of South Africa. His area of specialisation is HIV/AIDS care and support; childcare and protection; vulnerable populations; gender and social justice. He served as a supervisor for this study during the period 2021 to 2022, which is the same period when data collection was conducted. His primary role was to oversee the entire project and guide the first author throughout all the steps of the study by among others, reviewing the study plan, the data collection and analysis process as well as the writing up of the manuscript.