Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.59 n.4 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/59-4-1178

ARTICLES

Adapting the social work curriculum for relevance in a South African university: a collaborative autoethnography of social work academics during the KZN floods

Siphiwe MotloungI; Bongane MzinyaneII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Department of Social Work, Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8921-0367 motloungs@ukzn.ac.za

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Department of Social Work, Durban, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0684-0644 MzinyaneB@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article adopts collaborative autoethnography in order to critically reflect on the experiences of social work academics who integrated disaster-specific approaches to the social work curriculum of two undergraduate courses in a South African university. This curriculum adaptation was in response to the KwaZulu-Natal floods of 2022. The integration of topics such as green social work and disaster-specific trauma responses at an undergraduate level of social work is advocated. These collaborative autoethnographic accounts contribute important lessons for social work education, practice and research in the era of natural disasters exacerbated by climate change.

Keywords: Climate change; collaborative autoethnography; disasters; green social work; KZN floods; social work curriculum

INTRODUCTION

Social work education is the praxis of preparing future professionals for the real-life challenges that confront humankind. Recent natural disasters, such as the KwaZulu-Natal floods of 2022 (KZN floods), proved to be a contemporary challenge that called for interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary preparedness and responses that included social work. Sub-Saharan scholars such as Shokane (2019), Machimbidza, Nyahunda and Makhubele (2022) argue that the role of social work is undoubtedly becoming more significant in disaster management, prevention and response. This means that social work students need to be prepared for the consequences of natural disasters and environmental injustices. With the worsening effects of climate change and the associated natural disasters, it is crucial for social work academics to constantly embark on reflective teaching by constantly rethinking their teaching philosophy and content (Hubball, Pratt & Collins, 2005), in line with the context of evolving real-life challenges. Zeichner and Liston (2013) assert that the university environment is not insulated and/or immune from the outside environment. This implies that the entire system of higher education, including its students and academics, is inevitably affected by the context of its environment and ecosystem.

Undoubtedly, natural disasters lead to a range of unforeseen socio-economic consequences, spatial displacement and psychosocial effects such as trauma, grief and bereavement. Interdependencies between psychosocial issues, spatial/physical environmental issues, socioeconomic challenges and structural inequalities are important factors in the discourse on climate change and social work education. As such, there is a need for the adaptation of social work curricula to deal with the current challenges that have been brought about by climate change and its inherent disasters. Internationally, the third item on the Global Agenda for Social Work and Social Development: Commitments to Action stipulates the importance of 'working towards environmental sustainability' (IASSW, ICSW & IFSW, 2012). On the same note, Dominelli (2012) also pioneered the introduction of the Green Social Work framework, in which she defined as a holistic approach to environmental crises that have challenged the social work profession to incorporate its principles, values and concerns over environmental degradation, and the disasters associated with this, into daily routine mainstream practice. This signifies the importance of incorporating the discourse of climate change into social work education, practice and research, and strengthening its import. This is particularly pertinent for the South African context, which has been affected by several disasters brought on by climate change in recent years and currently, as is the case with many countries around the world.

It is against this background that we critically reflect on our experiences of teaching undergraduate social work students during and after the KZN floods. We have adopted collaborative autoethnography as our methodological framework in order to jointly reflect on our teaching practice and rethink the curriculum implications that emerged from the KZN floods during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the main part of this article, we reflect on the challenges that we noted during the KZN floods and, importantly, on the actual and potential adaptations of the curriculum and the pedagogy of undergraduate social work modules in a time of worsening natural disasters.

THEORETICAL ORIENTATION

Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory (Darling, 2007; Neal & Neal, 2013) was used to chart our reflections regarding our response to the KZN floods at the micro, meso and macro environmental levels in terms of teaching and learning. The focus of the theory is on the way the different types of environmental systems impact on human lives. Of importance was the holistic understanding of the interface between humanity and the environment, but more specifically the natural environment (ie. KZN floods). It was evident that our experiences as well as those of our students (at the micro level) affected teaching, learning (at the meso level) and policy imperatives (at the macro level) that need to be part of social work practice and learning in South Africa. The need for integrated disaster-responsive approaches in social work at the various environmental levels was therefore apparent.

SOCIAL WORK AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE CONNECTION?

For over two decades, the profession of social work called for action to address the issues of environmental challenges, climate change and disasters (Jackson, 2017). However, action to integrate green social work into social work curricula and practice has been slow and gradual in the South African context. This is confirmed by Matlakala, Nyahunda and Makhubele (2021:89), who found in their study that "social workers lack [...] proper training to deal with the victims and survivors of natural disasters". Green social work focuses on the particular role that ecological factors play in maintaining the well-being of individuals and communities (Papadimitriou, 2020). Whereas social work is a profession that is concerned with the personin-environment, which derives from the ecological systems theory, the focus is on the social environment and not the physical environment. When dealing with social issues from the micro, meso and macro levels, however, there is a need to widen the focus in order to include the natural environment and the associated ecological factors (Cumby, 2016; Shaw, 2011). The integration of green social work into African and South African social work curricula and practice has been particularly slow and inadequate. This is despite the concentration of some of the most marginalised and vulnerable populations being in Africa and the well-documented fact that the effects of climate change disproportionately affect the most vulnerable and marginalised (Achstatter, 2014; Cleary & Dominelli, 2020; Cumby, 2016; Dominelli, 2014; Dorn, 2019; Forman, 2022; Jackson, 2017; Matlakala, Makhubele & Nyahunda, 2022; Papadimitriou, 2020; Shaw, 2011). Furthermore, climate change brings to the fore social justice issues, because its effects often intensify the existing poverty in these contexts, making environmental justice an important factor to deal with for social workers. This is supported by Cumby (2016:15), who states that "social work service users are likely to be amongst those disproportionately affected by climate change".

At an international level, goal 13 of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations 2030 (SDGs) expresses the commitment of world nations to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impact (cf. Arora & Mishra, 2019). On the same note, the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) and the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW), to which most social work educational institutions including South Africa belong, have clearly delineated the importance of social work intervention in the social, natural and geographic environments. Furthermore, the IFSW and IASSW were involved in updating the Global Standards for Social Work Education and Training (IFSW & IASSW, 2020:12), which has a standard which stresses the need for "the critical understanding of the impact of environmental degradation on the well-being of our communities". Given the impact of environmental challenges, including climate change, it has therefore become imperative to include the related issues in social work education, as highlighted by the above international social work educational bodies.

In the South African context, the effects of climate change have been felt with rising temperatures, water shortages and especially with flooding, the most recent instance of which was the devastating floods on 11 and 12 April 2022 on the coast of the province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), more specifically Durban. Bouchard et al. (2022) argue that the KZN floods were among the deadliest natural disasters to strike South Africa in the twenty-first century and the deadliest since the floods of 1987, with 300 millimetres of rain falling in a single day. As a result of this flooding, over 400 people died, several bridges, roads and other kinds of infrastructure were damaged, and more than 40 000 homes were demolished, with some people's bodies not ever found (Makhaye, 2022). Social work practitioners and social work academics in KZN were involved in providing relief to the victims of the floods in terms of psycho-social support and material assistance (Ngcobo, Mzinyane & Zibane, 2023). That disaster, however, prompted serious discussions of the way the current South African Social Work curriculum deals with current environmental issues, specifically the devastating effects of climate change. According to Dominelli (2014:338-339)

social work educators and practitioners have an important role to play in developing and sustaining an environmental justice that upholds human and citizenship-based rights and in ensuring that such concerns are covered in social work's curricula.

The South African Council of Social Service Professions (SACSSP) is the statutory body that all South African social workers who have qualified as social workers belong to. It plays a comprehensive role in setting standards for education and training of social work practitioners to determine, guide and direct the structure of social service professions in South Africa, and in passing policy resolutions (SACSSP, 2007). The SACSSP, in Section 5.5 which focuses on social workers' ethical responsibilities to the broader society with respect to social development and public emergencies, points out that:

5.5.1Social workers should promote the general development of society, from local to global levels and the empowerment of their communities and their environments. Social workers should advocate for living conditions conducive to the fulfilment of basic human needs and should promote social, economic, political and cultural values and institutions that are compatible with the realisation of social justice.

5.5.2Social workers should provide appropriate professional services in public emergencies to the greatest extent possible.

5.5.3a Social workers should engage in social andpolitical action that seeks to ensure that all people have equal access to the resources, employment, services and opportunities they require to meet their basic human needs and to develop fully. Social workers should be aware of the impact of the political arena on practice and should advocate for changes in policy and legislation to improve social conditions in order to meet basic human needs and promote social justice (SACSSP, 2007:42).

With reference to the above responsibilities outlined by the SACSSP for social workers, there are no specifics about what "empowering the environment" means. The SACSSP elucidates that the fulfilment and meeting of human needs, providing equal access to resources and social justice are important, but there is no mention of environmental justice. This is despite the fact that global environmental changes and the reverberations of climate change abound the world over. Additionally, the consequences of climate change affect living spaces, food supplies, water and air quality, infrastructure and mental health, as well as leading to population displacements and exacerbating existing inequalities (Dominelli, 2014; Dorn, 2019; Forman, 2022; Jackson, 2017). These changes are most poignantly in the South African context, especially among the poor. In comparison, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), the body subscribed to by social workers in the United States, added environmental justice to its social work list of core competencies and launched the Committee on Environmental Justice in 2015 (Forman, 2022; Jackson, 2017). This highlights the importance of the need to adapt legislation, social policy and social work curricula accordingly in the South African context to meet current and future environmental challenges. A discussion of our methodology for this study addressing these issues follows below.

METHODOLOGY

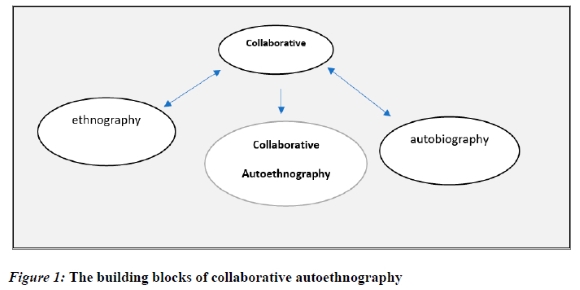

In this article, we adopted a qualitative approach called collaborative autoethnography as our epistemological point of departure. The term collaborative autoethnography has three building blocks: collaboration, autobiography and ethnography. According to Chang, Ngunjiri and Hernandez (2013), the term 'collaborative autoethnography' is actually oxymoronic, in that ethnography is a study of culture and habits that enables the researcher to capture and give an intimate descriptive and interpretive account of participants' experiences (Zibane, 2017), while autobiography is defined by Staude (2005:249) as "a dialogue of the self with itself in the present about the past for the sake of self-understanding". Yet despite this potential conflict of meanings, the methodological genre of autoethnography has been theorised, validated and widely adopted by a number of scholars (Anderson, 2006; Atkinson, 2006; Roy & Uekusa, 2020; Wall, 2016). Chang et al. (2013) expanded the concept of autoethnography by introducing the notion of "collaborative" into it. Collaborative autoethnography is still a research method based on self-inquiry, but one that is collaborative in that authors reflect scholastically while learning from each other (Chang et al., 2013). It is important to note that some scholars have referred to this method by different terms: duo-autoethnography (Lund & Nabavi, 2008) and community autoethnography (Toyosaki, Pensoneau-Conway, Wendt & Leathers, 2009); but the differences in these labels are a matter of nuance and non-substantive. In essence, the approach refers to a procedure for self-inquiry that includes more than one researcher. We developed a graphic (Figure 1) to illustrate the building blocks of this concept.

This methodology was appropriate in order to draw from the dual lenses of social work academics who have similarities:

• Firstly, we are both social work academics employed in the same institution;

• Secondly, we are both teaching undergraduate Social Work programmes in the same institution;

• Lastly, we both modified our curriculum during the KZN floods in order to simultaneously strengthen the process of students' preparedness for practice and also address their mental health struggles during that time.

Collaborative autoethnography as a process empowers researchers to engage in a collective examination of individual autobiographies to understand a sociocultural phenomenon (Chang et al., 2013).

Chang et al. (2013) posit that this method entails four steps of data collection and analysis: (1) preliminary data collection, (2) subsequent data collection, (3) data analysis and interpretation, and (4) report writing. We adopted these steps in our collaborative autoethnographic reflection, as outlined in more specific detail below.

In the execution of this research method, the preliminary data collection started with a reflective conversation where we shared and debriefed about our experiences of the KZN floods and the implications for our respective social work modules. This process started informally but during the next meeting there was formalised 'sharing' and 'probing' by both of us. The phase of the data collection was continued by writing up the minutes of our initial two meetings, followed by detailed individual self-writing about our subjective experiences of teaching and learning during the KZN floods. Through the individual interpretation of the minutes of the meetings and the individual journaling process, we started to create individualised meanings of our experiences, which we later shared with each other and combined for analysis. The data analysis and interpretation were done through the exchange of journal notes and the collaborative familiarisation of both our 'raw individual reflections'. Thereafter, we initiated the process of meaning-making and thematization of our reflections. Based on the analysis process we developed two thematic reflections as presented below. We later discussed the individual reflections in order to refine our understanding, rethink the curriculum and formulate recommendations for social work education, practice and research. Based on our experience of this research approach through applying the steps outlined by Chang et al. (2013), we posit that this research orientation is simultaneously interpretative and critical. Through collaborative autoethnography, we managed to "consciously adopt a critical and reflective stance" in relation to our research, as advocated by Pozzebon (2004:277), who strives for the normalisation of critical-interpretative research.

The ethical aspects of research have always been an evolving discourse, "especially for ethicists and philosophers of science" (Kazmierska, 2020:119). In this collaborative autoethnography we also ensured the ethical integrity of our project by adopting the axiomatic ethical principle of the need to avoid, mitigate and be transparent about any form of potential harm that may arise from the execution of a research project. Despite this reality, the conceptualisation and writing-up processes of this article still presented us with an ethical quandary: whether to apply for an independent ethical clearance in order to execute this research methodology or not. This was because this article was based on collaborative reflections based on our teaching practice as social work academics. The reality that this article is reflective and did not include any third-party participants brought some level of comfort that we were not likely to cause harm during the execution of this research project. It is noteworthy that in this article we are reflecting on our own personal experiences on subject matter that is not sensitive. However, this is not to indicate that researching oneself is without ethical risk. For instance, Brian, Bains and Church (2019) posit that some self-research in some fields of science can be life-threatening i.e. chemical self-experimentations, amongst other forms of scientific research, including different types of research in social sciences. We were therefore also aware of the methodological positionality and ethical context of our article.

As a result, our scholarly consultation with recent publications on this ethical quandary provided direction (cf. Kazmierska, 2020; Lapadat, 2017). Kazmierska (2020:118) questions whether biographical researchers, in the social sciences, should be equally worried about "old ethical concerns in the face of new challenges and paradoxes". In his study, he examines the ethical requirements of social science methods as compared to those of natural sciences. He, therefore, argues that for biographical researchers to position their ethical standing they should question, "... where does this contemporary ethics discourse come from?" (Kazmierska, 2020:119). He further posits that the development of ethical reflection occurred along with the accelerated development of science, especially about those aspects of research work which were directly related to the study of human behaviour, interference in the human body, or experiments carried out on animals and sometimes on people. We, therefore, assessed our ethical rigour against this assertion.

Our stance on the non-application of ethical clearance was also affirmed by the other scholarly debates on the connection between reflections and ethics (cf. Lapadat, 2017; Roy & Uekusa, 2020). Lapadat (2017:589), in her research, examines the ethical requirements of different types of autoethnographies where she argues that both autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography, as research approaches, "address the ethical issue of representing, speaking for, or appropriating the voice of others". She argues that in these reflective and/or biographic methods, researchers instead write their own personal accounts, on their own behalf and without causing harm to their participants (cf. Roy & Uekusa, 2020). This means that the infliction of self-harm is less likely with this methodology, given the absence of participants. We could not intentionally cause harm to ourselves and/or uninformedly reflect in ways that would cause harm to ourselves. As a result, the need to apply for ethical clearance was invalidated. On the same note, Praeg (2017) emphasises the need for researchers to be emancipated by the processes of writing. He differentiates between "writing what I like and writing what I must" (Praeg 2017:293). In his argument, he highlights the importance of dismantling some of the processes of writing that are not always a necessity. Praeg (2017:4), argues that

when I write what I like, I believe in the emancipatory potential of thinking and writing, but when I write what I must, there is an already implicit foreboding that thinking and writing are weighed down by history and complexity to such as extent that what is being thought and written may not easily translate into an emancipatory project.

Similarly, this collaborative autoethnographic article was emancipatory because it dismantled the need for external interpretation of our ethical considerations, analysis of our views, and a represented write-up of knowledge.

The use of this method also prompted the realisation that it is emancipatory and based on the co-creation of knowledge between the 'sources of data' and the 'researchers', who are ultimately the same people. More importantly, it may involve people who are equally in control of a project. Similarly, in conducting this research, we did not experience any power dynamics because of our similar profile as indicated earlier in this section.

The next section presents our reflections.

KEY REFLECTIONS

The key reflections of this article are presented in three parts: Part 1 presents the reflections of the first author; Part 2 presents the accounts of the second author; Part 3 presents the joint interpretative discussion of our collective accounts with reference specifically to green social work and the social work undergraduate curriculum.

The themes were: (1) My undergraduate module, "floods of challenges" and the autobiography; and (2) My undergraduate module, teaching content and the floods: the turning point?

Part 1: First reflective account

My undergraduate module, "floods of challenges" and the autobiography

The social work module that I teach at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban is SOWK401 Advanced Clinical Methods. The focus of this specific module is to introduce fourth-year social work students to the topics of mental health and to focus more specifically on mental illness, trauma, addiction and bereavement. Since the University is in the KwaZulu-Natal province, most of our students reside in the province. It is important to note that the KZN floods occurred during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This meant that most students had been studying and/or working from home for almost 3 years (Mzinyane & Motloung, 2022). This meant they had been dealing with the ravages of COVID-19, often while balancing domestic issues and academic work. Some reported challenges with spaces that were not conducive to study, network challenges, electricity challenges, illness, domestic violence, grief and bereavement and other mental health issues. All these challenges were exacerbated by the KZN floods. In the same vein, I was dealing with similar challenges as their lecturer, the only difference being that I was balancing working from home instead of studying. Moreover, in July 2021 in the middle of the pandemic, there was rioting in KZN which culminated in the looting and burning of shops and damage to infrastructure during protests against the imprisonment of former President Jacob Zuma; over 330 deaths were reported, most of whom had been shot by civilians. This resulted in the loss of jobs, trauma, racial tensions and fear. When the KZN floods hit on 11 and 12 April 2022, South Africans were therefore still in recovery from the collective trauma of COVID-19 and the violent rioting, that accumulated over two years. The floods were therefore yet another trauma upon other traumas. The floods affected me as an academic staff member as well as the students. There were challenges at varying levels of severity with loss of electricity, no water, death, damage to infrastructure or homes, and displacement when the homes of some people were completely lost.

In the lectures, the issues of mental health, trauma, bereavement and addiction were therefore not just being discussed hypothetically, but literally experienced by the students and myself. Most students were unable to attend lectures and therefore adjustments needed to be made in terms of rescheduling of lectures. Those who did attend lectures ultimately were very emotional and lectures offered an opportunity to vent and debrief. The importance of healing the healer became a factor (Rakel & Hedgecock, 2008). Murphy (2022) refers to social work students as 'wounded healers' who require self-introspection, self-awareness and therapeutic engagements before they enter the field of social work practice. In the context of this article the concept of "healing the healer" can refer to the process of allowing students to reflect on their own lives and experiences as a way of healing themselves and preparing them to be better therapists. It became apparent that there is a need to develop a mindset that does not view individuals (students in this instance) as separate from their environment (Cumby, 2016).

Considerations of using autobiography as a way to manage the students' emotions became more apparent as students needed to express their traumatic experiences during the processes of teaching mental health issues in my lectures. A shift from conventional teaching became essential during this time of simultaneous disasters to prepare students for their future. According to Staude (2005), writing an autobiography is a therapeutic and useful spiritual process for social workers. The adoption of this method could also be important for research purposes, where students' experiences could be part of the data used to inform curricula and healing-the-healer policies in social work education (Rakel & Hedgecock, 2008). The multitude of traumas that students and I faced, especially the KZN floods, brought to the forefront the absence of a curriculum that clearly dealt with environmental or green social work. The need for psycho-social counselling during this time became especially relevant, something which is sorely lacking in our context when natural hazards hit, as highlighted by Matlakala et al. (2022). On the educational front, this has a particular urgency.

The advocacy role at the macro level is also another important role highlighted by the SACSSP (2007) in terms of social and political action needed to ensure access to resources as well as social policy changes that will advance environmental justice. In terms of individual and community work, environmental intervention strategies need to be incorporated into the day-to-day work of social workers, where physical environmental assessment is incorporated into psycho-social assessment (Cumby, 2016). Moreover, Cumby (2016) highlights social work skills in terms of supporting the marginalised and oppressed as being key to the achievement of social justice. Bearing in mind their varied skills at the micro, meso and macro levels, social workers need to work to actively shape responses to disasters in meaningful and context-specific ways in communities (Cleary & Dominelli, 2020)

Cleary and Dominelli (2020) further advocate for the importance of self-care when dealing with disasters, because of the gruelling and exhausting work entailed.

Below is the reflective account of the second author.

Part 2: Second reflective account

My undergraduate module, teaching content and the floods: The turning point?

As argued earlier in this article, the KZN floods were one of the deadliest natural disasters to strike South Africa in the past three decades and the most destructive since the floods of 1987, with 300 millimetres of rain falling in a single day (Bouchard et al., 2022). At a personal level, I was neither prepared for such destructive rainfall in an Autumn season nor was I prepared for its impact on the lives of the community of Durban and my students. I can genuinely state that as an individual I was unfamiliar with the importance of green social work in the context of climate change, but the KZN floods were a wake-up call for me as an academic. Because of the infrequent nature of floods in the province and the rare involvement of social workers in the management of disasters in previous years, climate change was not a pedagogical focus for me or for social workers in general. When the floods hit, I was teaching a year-long third-level undergraduate practice module called: Social Work Practice Three (SOWK320-H0). This social work module is practical in its nature and is designed to prepare students for real-life challenges at an individual, group and community level. It teaches students to also translate theory into practice. According to the University of KwaZulu-Natal's College of Humanities Handbook of 2022, this module aims to help students develop a critical understanding and practice skills in three areas:

• Working with individuals and families;

• Working with groups in the school/organisation context;

• Working with organisations and communities.

It is important to note that this module has practical components where students would be placed in external social work organisations, with clients, under the mentorship of a registered social worker. Their placement is for a period of three weeks during their mid-year vacation. As a result, it is crucial that this module prepare them for the real-life challenges of their clients. I facilitate the content on community work practice during the second quarter of the year, which is a few weeks before they go to their field placement. Normally, I would allocate case studies of real-life challenges for students to analyse and demonstrate their ability to apply the knowledge that they had accumulated in the previous years of the Bachelor of Social Work degree. Most interestingly, I would adopt a wide range of case study topics, such as rural development, informal settlement and poverty, but not anything on the topics of disaster management and green social work.

During this case study process, I would normally select community work themes or topics that are subjectively related to social problems that are my research niche or preferred area. The magnitude of the floods, however, changed the trajectory of my teaching. As per the norm, our third-year students were due for their third-year work integrated learning, with communities after my term of teaching. Therefore, I had to select a case study theme that was timely and happening in the communities in order for the students to understand their role in disaster response and disaster management.

After realising the effects of the floods in the wider community, I then thematized my case studies to focus on the KZN floods. Students had to select a community problem and devise a community project proposal as a social work response to floods. After allocating this task, I received a lot of complaints from students, who mentioned that they were not confident about dealing with the aftermath of a flood disaster. The theoretical part of disaster-specific social work had never been covered in their curriculum in previous years. Therefore, their discomfort was understandable, but I insisted that they should use their social work creativity, knowledge and skills to initiate intervention plans for a community that was affected by the floods. This then allowed them to be creative and search for literature relevant to the assignment problem that I had allocated for them. To my surprise, in a number of assignments, the theme of green social work emerged, a concept that I was not familiar with. In their previous years, they had never been exposed to the concept of green social work. However, my presenting them with this challenge pushed the students to research beyond their comfort zone. A key lesson was that as the world changes, the problems that we face as a profession also change. It is therefore important to train students to become creative thinkers and resourceful practitioners, even amid unexpected occurrences such as natural disasters.

Part 3: Discussion of the reflections: Dual experiences of curriculum adaptation

The reflections above highlight the fact that social work challenges are not static but evolving and therefore demand adaptation of social work education and practice. Specifically, climate change should not be the sole focus of fields such as Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), but Social Work has a role in advancing the climate change discourse as well.

In our reflections, we acknowledged that social work education needs to be responsive to the real-time challenges of our students and communities.

In her reflection, the first author noted that the KZN floods came on top of a myriad of other socio-economic, psycho-social and environmental challenges and traumas that students, communities and academics alike were facing. These included challenges that were associated with COVID-19, the July 2021 unrest and looting, inter alia. Additionally, the need to incorporate autobiography, reflections and programmes geared at healing the healer for social workers, social work academics and social work students was highlighted (Rakel & Hedgecock, 2008). Based on our reflections above, it is noticeable that the KZN floods prompted us to specifically acknowledge curriculum gaps as well as the evolving realities of those whose interests we serve. The second author illustrates that the subject of climate change in social work modules was unfamiliar, and hence uncomfortable, for academics and students alike. However, the process of adapting the thematic contents of the module called for a pedagogy of discomfort, which is described by Zembylas and McGlynn (2012) as an approach to social justice education that unsettles the cherished beliefs of teaching. It posits that evoking discomforting feelings is important when challenging the dominant discourses of social work education (Perumal et al., 2021).

In these reflections, we were able to dissect the challenges faced by students and communities from the micro, meso and macro levels through the ecosystems theory. The first author posits the importance of dealing with the "intrapersonal" (micro) challenges and therefore healing the healer during the process of social work education (Rakel & Hedgecock, 2008). Through her reflection, it is clear that social work education should be transformative in that it allows students the opportunity to reflect on their personal challenges. On the other hand, the second author argues that social work education should afford students the opportunity to reflect on the practice challenges of social work service users (meso), while exploring disaster-specific social work practical responses. Moreover, the SACSSP and other higher education and social development bodies need to definitively include green social work and environmental justice as core areas in South African social work education and in social policy in general (macro).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the era of unpredictable challenges that affect people, it is apparent that climate change is an emerging and evolving area for social work education, practice and research. This is because of its multiple effects that include socio-economic consequences, spatial displacement and psychosocial challenges such as trauma, grief and bereavement for the survivors and victims of natural disasters. Given the context explained above, we find it appropriate to argue for a social work education that prepares students for the multifaceted challenges of climate change. This article highlights the importance of being flexible and context-conscious academics in the process of social work education.

Beyond being a collaborative autoethnography, this article was not only a critical reflective exercise for us as academics, but also a contribution to the discourse of green social work and social work education. Our reflections indicated that we both initially lacked an appreciation of climate change as a relevant focal point for social work education. Following sensitisation to this need, the need to integrate green social work and disaster-specific trauma responses at the social work undergraduate level became evident.

The following are our recommendations.

• Given the worsening effects of climate change, the framework of green social work needs to gain considerable momentum in social work education, practice and research.

• Themes such as green social work and the climate change discourse need to be integrated into theoretical and practice-based social work modules.

• Critical reflective teaching should be routine for social work academics in order to evaluate their own biases and acknowledge gaps, and hence adapt social work

pedagogy.

• Social work students need to be prepared for the unexpected and the evolving nature of social challenges of our world, and their need to be critical thinkers needs to be continually emphasised.

• Unconventional methods such as autobiography need to be integrated into the curriculum as social work tools of teaching, learning and research for social work students.

• The explicit inclusion and detailed consideration of green social work and environmental justice needs to be an integral part of social policy and social work practice and education in South Africa.

REFERENCES

Achstatter, L. C. 2014. Climate change: Threats to social welfare and social justice requiring social work intervention. 21st Century Social Justice, 1(1): 1-22. [ Links ]

Anderson, L. 2006. Analytic autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4): 373-395. [ Links ]

Arora, N. K., Mishra, I. 2019. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and environmental sustainability: Race against time. Environmental Sustainability 2, 339-342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-019-00092-y. [ Links ]

Atkinson, P. 2006. Rescuing autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, no. 35(4): 400-404. [ Links ]

Bouchard, J. P., Kramers-Olen, A. L., Padmanabhanunni, A., Pretorius, T. B. & Stiegler. N. 2022. Global warming and psychotraumatology of natural disasters: The case of the deadly rains and floods of April 2022 in South Africa. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique, 3311(2022): 1-6. [ Links ]

Brian P. H., Bains, W. & Church, G. 2019. Review of scientific self-experimentation: Ethics history, regulation, scenarios, and views among ethics committees and prominent scientists. Rejuvenation Research, 22(1): 31-42. [ Links ]

Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F. & Hernandez, K. C. 2013. What is collective autoethnography? In: Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F. & Hernandez, K. C. (eds.). Collaborative autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Cleary, J. & Dominelli, L. 2020. Social work and disasters: Systematic literature review, main report. Stirling Scotland: University of Stirling, Faculty of Social Sciences. [ Links ]

Cumby, T. J. 2016. Climate change and social work: Our roles and barriers to action. Master's thesis. Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada. [ Links ]

Darling, N. 2007. Ecological systems theory: The person in the center of the circles. Research in Human Development, 4(3-4): 203-217. [ Links ]

Dominelli, L. 2012. Green social work: From environmental crises to environmental justice. Bristol: Polity Press [ Links ]

Dominelli, L. 2014. Promoting environmental justice through green social work practice: A key challenge to practitioners and educators, International Social Work, 57(4): 338-245. [ Links ]

Dorn, C. 2019. Climate change and health: A call to social workers. Summer Practice Perspectives, 2019: 1-5. [ Links ]

Forman, A. 2022. Social work, climate change, and environmental justice: A complete guide. MSW Online, 25 March 2022: 1-8. [ Links ]

Hubball, H. T., Pratt, D. D. & Collins, J. B. 2005. Enhancing reflective teaching practices: Implications for faculty development. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 35(3): 57-81. [ Links ]

International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW), International Council on Social Welfare (ICSW) & International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW). 2012. The global agenda for social work and social development: Commitment to action. [Online] Available: https://www.ifsw.org/social-work-action/the-global-agenda/ [ Links ]

International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) & International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW). 2020. Global standards for social work education and training (GSSWE). [Online] Available: https://www.ifsw.org/global-standards-for-social-work-education-and-training/ [Accessed: 27/09/2022]. [ Links ]

Jackson, K. 2017. Climate change and public health: How social workers can advocate for environmental justice. Social Work Today, 17(6): 1-7. [ Links ]

Kazmierska, K. 2020. Ethical aspects of social research: Old concerns in the face of new challenges and paradoxes. A reflection from the field of biographical method. Qualitative Sociology Review 16(3): 118-135. [ Links ]

Lapadat, J. C. 2017. Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(8): 589-603 [ Links ]

Lund, D. E & Nabavi, M. 2008. A duo-ethnographic conversation on social justice activism: Exploring issues of identity, racism and activism with young people. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 10(1): 27-33. [ Links ]

Machimbidza, D., Nyahunda, L. & Makhubele, J. 2022. The importance of social work roles in disaster risk management in Zimbabwe. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 27(2022): 717-726. [ Links ]

Makhaye, C. 2022. KZN flood disaster: 'Water was quickly rising and I saw that my house would fall.' Daily Maverick, 24 May 2022. [Online] Available:https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-05-24-mop-up-begins-after-devastating-floods-strike-kzn-twice-in-just-over-a-month/. [ Links ]

Matlakala, K. F., Nyahunda L. & Makhubele, J. C. 2021. Challenges faced by social workers dealing with victims and survivors of natural disasters. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences 9(3): 189-197. [ Links ]

Matlakala, F. K., Makhubele, J. C. & Nyahunda, L. 2022. Social workers intervention during natural hazards. Jamba Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 14(1): 1-6. [ Links ]

Murphy, E. 2022. A Reflection on social work students as the "wounded healer". Relational Social Work, 6(1). https://rsw.erickson.international/archivio/vol-6-n-1/a-reflection-on-social-work-students-as-the-wounded-healer/ [ Links ]

Mzinyane B. M. & Motloung S. 2022. Reflecting on digital summative assessments during COVID-19 lockdown in a South African University: The accounts of social work academics. In: Ramrathan, L., Hoskins, R. & Singaram, V. S. (eds.). Assessment through digital platforms within Higher Education studies. Volume 12. Alternation Book Series. Pietermaritzburg: CSSALL Publishers. [ Links ]

Neal, J. W. & Neal, Z. P. 2013. Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Social development, 22(4): 722-737. [ Links ]

Ngcobo, N., Mzinyane, B. & Zibane, S. 2023. Responding to concurrent disasters: Lessons learnt by social work academics engaging with flood survivors during a COVID-19 pandemic in South African townships. In: Joseph, D. D. & Doon, R. (eds.). The impact of climate change on vulnerable populations: Responses to a changing environment. Basel: MDPI Publishers. [ Links ]

Papadimitriou, E. 2020. Defining green social work. Social Cohesion and Development, 15(1): 139-152. [ Links ]

Perumal, N., Pillay, R., Zimba, Z. F., Sithole, M., van der Westhuizen, M., Khoza, P., Nomngcoyiya, T., Mokone, M. & September, U. 2021. Autoethnographic view of South African social work educators during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Highlighting social (in)justice. Social Work/Maatskaplike Work, 57(4): 393-406. [ Links ]

Pozzebon, M. 2004. Conducting and evaluating critical interpretive research: Examining criteria as a key component in building a research tradition. In: Kaplan, B., Truex, D. P., Wastell, D., Wood-Harper, A. T. & DeGross, J. I. (eds.). Information systems research: Relevant theory and informed practice. Springer: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Praeg, L. 2017. Essential building blocks of the Ubuntu debate; or: I write what I must. South African Journal of Philosophy, 36(2), 292-304. [ Links ]

Rakel, D. P. & Hedgecock, J. 2008. Healing the healer: A tool to encourage student reflection towards health. Medical teacher, 30(6): 633-635. [ Links ]

Roy, R. & Uekusa, S. 2020. Collaborative autoethnography: "Self-reflection" as a timely alternative research approach during the global pandemic. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(4): 383-392. [ Links ]

Shaw, T. V. 2011. Is social work a green profession? An examination of environmental beliefs. Journal of Social Work, 13(1): 3-29. [ Links ]

Shokane, A. L. 2019. Social work assessment of climate change: Case of disasters in greater Tzaneen municipality. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 11(3): 1-7. [ Links ]

South African Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSP). 2007. Policy guidelines for course of conduct, code of ethics and the rules for social workers. Pretoria: SACSSP. [ Links ]

Staude, J. R. 2005. Autobiography as a spiritual practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 45(3): 249-269. [ Links ]

Toyosaki, S., Pensoneau-Conway, S. L., Wendt, N. A. & Leathers, K. 2009. Community autoethnography: Compiling the personal and resituating whiteness. Cultural Studies: Critical Methodologies, 9(1): 56-83. [ Links ]

Wall, S. S. 2016. Toward a moderate ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406916674966. [ Links ]

Zeichner, K. & Liston, D. 2013. Reflective teaching: An introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zembylas, M. & Mcglynn, C. 2012. Discomforting pedagogies: Emotional tension, ethical dilemmas and transformative possibilities. British Educational Research Journal, 38(11): 41-59. [ Links ]

Zibane, S. 2017. Negotiating sexuality: Informal sexual cultures amongst young people at a township high school in KwaZulu-Natal. Doctoral thesis. University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Article received: 2/12/2022

Article accepted: 2/5/2023