Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.59 n.4 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/59-4-1168

ARTICLES

An ecological systems approach to assess the well-being of street children in Zimbabwe: implications for developmental social work practice

Constance Gunhidzirai

University of Botswana, Department of Social Work, Gaborone, Botswana https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0339-6138 GunhidziraiC@ub.ac.bw

ABSTRACT

This study reports on an assessment of the well-being of street children in Harare Metropolitan Province in Zimbabwe using the ecological systems approach. This study was underpinned by a quantitative approach which employed a semi-structured questionnaire as an instrument of data collection. Based on survey data of 202 street children who were purposively sampled, the findings revealed that street children lack access to food, education, accommodation, health care and proper sanitation. Therefore, street children require multi-component psychosocial and developmental interventions to enhance their well-being. The recommendations drawn from the findings were submitted to the Department of Social Development in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: Child well-being; developmental social work; multiple deprivation; street children; poverty

INTRODUCTION

Street children live in an environment, which has an adverse impact on their growth and development. The social and economic domains of their well-being are significant because they directly affect their holistic development. The ecological systems approach (ESA) aids in examining the environment in its entirety and assessing its impact on human development. This study is unique because studies on street children in Zimbabwe have not addressed the implications of the environment on the well-being of street children. Street children refers to a girl or a boy under the age of 18 years who stays, sleeps and makes a livelihood on the streets without the guidance of an adult person (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], 2003). Street children refers to a boy or girl who has not achieved adulthood and for whom the street has become their habitation, a source of income and who is inadequately safeguarded and monitored by the parents or caregiver (Ogan, 2021). The estimated global child street population is between 100 to 150 million (UNICEF, 2017). In Zimbabwe, as Ndlovu and Tigere (2022) note, the number of street children is unknown because they do not have a permanent residence.

Street children are not a new phenomenon. They were visible on the streets at least as far back as World War II, when the economies of many countries collapsed, poverty increased and families and societies disintegrated (Ogan, 2021). At this time the increase of vulnerable children in the global north and south led to various social protection programmes and treaties being implemented to ensure that their needs were met (Ogutu, 2020). As a member of the United Nations, Zimbabwe adopted various treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which were incorporated into the Constitution of Zimbabwe in 1980 (Kanjanga & Chiparanga, 2015). This demonstrated the government's desire to enhance the well-being of the people. However, in upholding the rights of street children including the right to basic nutrition, shelter, social service and basic health care services, the government is faced with multiple challenges (Jakaza & Nyoni, 2018). According to Ndlovu and Tigere (2022), these challenges include the lack of financial resources and the unavailability of social workers as they migrate to greener pastures, in the process constraining the governments' efforts to address the challenges faced by vulnerable children.

Many push and pull factors trigger the proliferation of children in the streets in Zimbabwe. The push factors are the unfavourable circumstances that drive children to the street, such as abuse, neglect, poverty, adverse economic circumstances, natural disasters, family disintegration, parents' death, and divorce (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). Furthermore, social ties in extended families have broken down because of unemployment and lack of adequate income, which has led orphaned and other children to live or work on the streets (Ndlovu & Tigere, 2021). In Kenya, for example, family challenges forced children to work in the street environment to earn an income to meet basic household needs. The pull factors are the circumstances that attract children to street life, such as prospects of a better standard of living as well as peer pressure from fellow peers living independently and providing for their needs themselves (Human Rights Watch, 2020). Drawing from the push and pull factor perspective, it can be argued that the type of street environment influences a child's growth and development.

Despite growing research on the needs of street children in Zimbabwe, there is limited information on the economic and social risks they face on the streets. Therefore, this study applied the ecological systems approach to assess the influence of the environment on street children, including their well-being as they live or work in Harare Metropolitan Municipality.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The decline of the economy of Zimbabwe for various reasons has triggered many economic and social ills that include dire poverty and a sharp rise in the number street children. The prevailing social, economic and political conditions in Zimbabwe has created many risks for street children which hinder their growth and development. Despite all the government's efforts to address the plight of orphans and vulnerable children through various welfare programmes, the immediate needs of street children remain unmet. The consequences of a struggling social welfare system are evidenced by the rapidly growing number of street children as they scramble for survival in Harare Metropolitan Municipality, where this study was conducted.

While scavenging for survival characterises the daily lives of street children in Harare, the inconducive street environment has exposed children to various physical, social, economic, educational and psychological risks. To understand the plight of street children affecting their well-being adversely, the study adopted the ecological systems approach to examine the influence of the environment on the growth and development of a child. The researcher thereby attempted to demonstrate, among other things, how the volatility of the street environment can affect the well-being of street children. The goal of this study was to assess the well-being of street children to see if alternative mechanisms and strategies could be implemented by the government of Zimbabwe to enhance the living standards of street children.

The study answers the following research questions:

• Which gender and age groups are dominant on the streets?

• What are the challenges faced by street children concerning their well-being?

After this introduction, the study reviews the literature on street children in African cities, and specifically in Zimbabwe, in terms cial development policies for vulnerable children and child well-being using the ecological systems approach (ESA) and developmental social work approaches. The section after that offers a synthesis of the ecological approach and developmental social work and outlines the research methods. The next section focuses on data analysis and verification, followed by the presentation of the findings of the study and a discussion of the risks and implications for practice. The final section concludes the article and makes recommendations based on the study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A country's development is measured by, among other things, the extent to which it adopts a holistic approach to the well-being of children in the following domains: physical, psychological, social and economic (Sirgy & Lee, 2018). These domains influence each other and are directly linked to the well-being of children. These child well-being domains are vital in assessing whether a child is flourishing or experiencing positive development. The state of street children is a concern because they are experiencing numerous economic and social risks that inhibit their growth and development. Alex-Petersen, Lundborg and Rooth (2022) note that an adequate family income allows a child to attend school, have the basic necessities and access good health care, brightening their future prospects and creating better adult life opportunities. Patel et al. (2021) note that child well-being entails a combination of elements that influence a child's enjoyment and level of satisfaction, as well as affecting the conditions that support holistic development and growth. This shows that street children are at risk regarding their physical and mental growth, because they do not have systems on the streets that support and provide for their needs. Therefore, the welfare system, education system and health care system need to work together to implement an intervention that seeks to address the risks faced by street children to attain overall happiness, achieve their goals and enjoy life (Salihu, 2019).

Street children in African cities

This study reviewed the empirical literature on the experiences of street children in various African cities. The increase in the number of street children in Africa is a social concern to all governments and stakeholders. Ogutu (2020) noted over 150 000 street children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 30 000 in Accra, Ghana, 30 000 in Kinshasa, Congo, one million in the cities of Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt, and between 250 000 to 300 000 in Kenya. Most of these children reside or work on the streets of metropolitan cities and big towns, which they perceive to offer social and economic opportunities (Reza & Bromfield, 2019). Drawing from the statistics above, governments, as the primary custodians of children, struggle to uphold children's rights and best interests in all circumstances.

Street children in African cities survive by doing part-time jobs such as recycling, car washing, baggage carriers as well as begging, to mention a few (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). These economic activities help them earn some income for their necessities on the streets. Because of the lack of accommodation and the nature of the informal economic activities the street children engage in, most of them sleep at filling stations, under bridges, at bus terminuses and anywhere that they can find a space to lie down (Maepa, 2021). This makes them vulnerable to abuse, including physical and psychological challenges, because of the hostility of their environment.

Except for Morocco, all African countries are members of the United Nations and have ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child Treaty (1989) adopted into their constitutions (UNICEF, 2015). This Convention considers these countries responsible for safeguarding and promoting children's rights. African governments have adopted programmes to ensure that the needs of vulnerable children are met. In Zimbabwe, the government has implemented social protection programmes and services to address the needs of orphans and vulnerable children (UNICEF & Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, 2016).

Street children in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a landlocked African country in the Southern Hemisphere. The capital city is Harare, with around five million people who reside in suburbs, high-density areas, dormitory towns and informal areas (Republic of Zimbabwe, 2014). For the past two decades in Zimbabwe Street children have become an increasingly common feature of Harare's urban landscape, because of increased economic suffering and poverty in the country (Jakaza & Nyoni, 2018). The Department of Social Development (DSD) in Zimbabwe provided various social welfare services to vulnerable groups. However, the collapse of the economy led to reduced government spending on public services, perpetuating poverty among vulnerable populations who relied on government assistance (Kaseke, 2011). This dire situation forced children to embark on various kinds of economic activities on the streets. UNICEF and the Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare (2016) reported there are around 5 000 street children who receive one meal per day and donations from various welfare organisations in Harare Metropolitan Province. However, other street children refuse to be on the DSD street children database because they do not want to be categorised as "vulnerable" for fear of being detained and placed in children's homes (Chitiyo, 2017).

Social development policies for vulnerable children in Zimbabwe

The DSD collaborates with welfare organisations such as Streets Ahead, Cathedral Church, Just Children Foundation and House of Smiles to meet the needs of street children in Harare Metropolitan Province. These welfare organisations provide various social interventions such as therapeutic counselling, health care services, provision of food and supply other necessities to enhance the well-being of children on the streets (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). The stakeholders in the welfare system, such as those mentioned above, rely on donations, which means that their services to street children are limited.

The DSD implemented programmes such as Free Treatment Order, Child Adoption, Institution Care, Basic Education Assistance Module, and Harmonised Cash Transfer Programme (HSCT) to assist vulnerable children in Zimbabwe (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). These programmes seek to ensure that children in difficult circumstances, such as street children, obtain comprehensive social welfare services to address their needs. However, the DSD is experiencing a shortage of social workers and funds, as well as corruption and other challenges, which constrain the provision of welfare services (Jakaza & Nyoni, 2018). This indicates that the government as the primary custodian of children is not adequately upholding children's rights.

CHILD WELL-BEING, THE ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS APPROACH (ESA) AND DEVELOPMENTAL SOCIAL WORK

The conceptual framework which underpins this study is the ecological system approach (ESA). Urie Bronfenbrenner (1986) devised the ESA in the 1970s to explain how social environments influence the child development process. This approach highlights the significance of observing children in their different environments, referred to as ecosystems. Those ecosystems include micro-, meso-, macro-, chrono- and exosystems, the children exist within the systems and the systems influence how the children develop and grow (Paquette & Ryan, 2009). According to Bronfenbrenner (1994), a microsystem refers to the immediate environment such as family, friends, community and school where a child interacts and forms personal relationships face-to-face. Children on the streets are part of street families and gang groups, and the socialisation they get impacts negatively or positively on their lives. The mesosystem involves the interactions and relationships formed within the microsystem (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). The relations between street children, their peers and members of the public influence their well-being because street children depend on them to provide for their needs.

Bronfenbrenner (1998:727-738) explained that the exosystem refers to the environment over which a child has no control such as "parent's workplace, social networks and communities". Street children are at risk because of social unrest on the streets where they reside. The macrosystem is a blueprint of belief systems, culture and ideologies (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). This study advocates for a change in mindset for all stakeholders to address the social and economic risks faced by street children by launching a developmental social welfare system. The chronosystem explains how the environmental changes during the life course affect child development and growth (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). In this research study the abuse, exploitation, neglect and abandonment experienced by street children affected their well-being. The ESA has been used in previous studies of children by Mhizha (2010) and Thor (2016). In these studies the ESA was used to assess factors that drove street children to the streets. In this study the ESA was used to examine how the specific urban environment influences the well-being of street children in Zimbabwe. The ESA is relevant to this study because street children face social and economic risks, which adversely affect their growth and thwart the desire to achieve their goals and ambitions in life.

Synthesis of the ecological approach and developmental social work

The ESA allows for a developmental assessment of the children’s well-being. In this study the questionnaire was structured to gather relevant data to assess the children and to make recommendations for developmental social work interventions. Furthermore, psychosocial and developmental interventions implemented by social workers are crucial to address the numerous deprivations faced by street children (Ashraf, Ibrar & Ullah, 2022). The ESA guides social work practice in Zimbabwe in formulating family tracing and family reunification programmes, which are vital in reducing the number of children on the streets. Social workers' interventions in the mesosystem are of significance because they help in rebuilding and restoring relationships of clients such as individuals, families and groups in communities. These interventions include psycho-social therapy, human capital development, literacy, public works, entrepreneurial programmes and housing policy, which are crucial in enhancing child well-being. The interventions mentioned above are vital as they help to address the needs of vulnerable children. This indicates that developmental social work draws on the ecological approach.

RESEARCH METHODS

The goal of this study was to assess the well-being of street children in Harare Metropolitan Province in Zimbabwe using the ecological systems approach. The researcher chose Harare Metropolitan Municipality, Zimbabwe because it is surrounded by suburbs such as Chitungwiza, Epworth and Norton that are experiencing high levels of poverty and unemployment. As these social ills are rampant in these suburbs, the children are forced to work or beg on the streets. This study is underpinned by a quantitative approach, based on numbers and statistics as data to generate the findings (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). The quantitative approach was applied in this study because it was the most effective strategy to gather information from 220 street children through the use of a survey questionnaire. Rubin and Babbie (2013) define a population as a set of entities where all the measurements of interest to the researcher are represented. In this study the population consisted exclusively of street children. It should be noted that the size of the population of street children in Harare Metropolitan Municipality is unknown because they are migratory. Kothari (2004) defines a sample selection as a plan for obtaining a sample from a given population. In this study the sample was made up of 202 participants. The sampling technique used was purposive. Maree (2007) states that purposive sampling means that participants are selected because of some defining characteristics that make them the holders of the data needed for the study. The purposive sampling technique was used to select street children because they had the relevant information on the social and economic risks they face on the streets and could indicate how these risks impact on their well-being.

A survey questionnaire was used to gather quantitative data from 202 street children aged between 6 and 18 years who took part in this study. The researcher used a semi-structured questionnaire to elicit data from the participants. Leedy and Omrod (2013) state that a semi-structured questionnaire is made up of open and closed-ended questions to gather qualitative and quantitative data. The semi-structured questionnaire was written in simple English language. It was subdivided into 5 sections and each section was designed to answer the research questions of this study. The researcher employed three research assistants to distribute the questionnaires to street children in public spaces that included Methodist Church, Harare Gardens, Anglican Church and the 4th and Copacabana bus terminus in Harare Metropolitan Province. These places are home to high numbers of street children during the day.

Ethical considerations

According to Neuman (2014), ethics in this context are the moral principles that guide research practice and clarify the boundary between ethical and unethical behaviour towards the participants of a study. The researcher obtained an ethical clearance letter (Reference Number: TANO11SGUN01) from the University of Fort Hare Research Ethics Committee, which stated that the research topic and data-collection instruments have been approved to gather data from the participants. The researcher applied for and was granted permission from the Head Office of the Department of Social Development (DSD) to interview street children of different age groups in the Harare Metropolitan Province, because most of them had no parents or guardians on the streets. The DSD is the primary guardian of street children in Zimbabwe.

Following the principle of informed consent, the researcher and the research assistants explained the purpose and objectives of the study to the street children. The street children signed the consent forms to indicate their willingness to participate in this study. To uphold the principle of voluntary participation, the street children were informed of their rights to withdraw from the study at any point without facing any consequences. The researcher further explained the principle of confidentiality and assured the street children that the information gathered would not be shared with any other persons. Confidentiality was maintained by using codes to conceal the names of the participants while presenting data. This study may have intruded upon the private lives of the street children as it explored the way they lived in the volatile conditions on the streets. Owing to the sensitive nature of certain elements of this study, the researcher offered to refer the street children who might have been affected psychologically to be debriefed by the social workers at the DSD.

Data analysis and verification

The quantitative data from street children were coded in Excel and run on Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26 of 2019, using descriptive analysis. Landau and Everitt (2004) explain that descriptive statistics are used for summarising data frequencies, and they measure central tendencies such as mean, mode and standard deviation. The data generated from this process were analysed using frequency distribution. The results produced in this analysis were presented in the form of pie charts, tables and bar graphs. To ensure the trustworthiness of the research findings, the researcher tested the reliability and validity of the questionnaire used in this study. Leedy and Omrod (2013) state that reliability implies that the same construct is measured under similar conditions repeatedly and the results remain the same. To test the reliability of the instrument used in this study, the researcher adopted the test-retest technique. To test that the instrument collected reliable data, the researcher used the same questionnaire on a sample of 50 street children from Harare Metropolitan Province. The findings obtained were similar, which confirms that the questionnaire was relevant to the research questions of this study.

Rubin and Babbie (2013) explain that validity is the capacity of a research instrument to measure what it is intended to measure. This research study adopted face validity because it used a questionnaire survey to gather quantitative data. In this study, the semi-structured questionnaire was given to two Post-Doctoral Fellows in the Department of Social Work at the University of Fort Hare to check whether the survey questions align with the research questions of the study, as well as to check whether they are written clearly and could measure what they were intended to measure.

FINDINGS OF THE STUDY

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of street children. The gender distribution showed that street boys constituted 76.7% and street girls, 23.3% of the population. There are more males on the streets than females. Maepa (2021) explains that girl's resort to early marriages or are involved in domestic work, hence their numbers on the streets are lower.

The findings show that the highest age group is children between 16-18 years (40.9%), and the lowest age group is children less than 10 years (19.8%). Gunhidzirai and Tanga (2020) reported that factors such as child abuse, neglect, increased poverty and death of parents or caregivers drove many children to live or work on the streets in Zimbabwe and South Africa. The age groups of street children in Zimbabwe varies because of the range of different personal and domestic circumstances they encounter in their lives.

The findings indicated that 75.7% of children live on the streets, while 11% of the children live off the street. Those who live on the streets considers the street environment as their permanent residence place and those who live off streets, spend most of their time during the day on the streets and at night sleep at home. The study conducted in Nigeria by Adaugo, Ibadin, Ofovwe and Abiodun (2020) corroborates these findings and report that majority of street children who have experienced many challenges in life live permanently on the streets and those children in dire poverty are embarking on various livelihoods to meet their needs. The microsystem in the ESA highlights the importance of relationships and contact with immediate families, 45.5% of street children are in contact with their families or relatives. Based on these findings, the reunification of family programmes and therapeutic services could be effectively implemented as a way of removing children from the streets, while rebuilding the broken relationships between children and parents.

This study's findings indicate that children who are maternal orphans constituted 53% of the sample, while 40.1% reported that their mothers are alive and 6.9% of the street children are not sure whether their mother is alive or deceased. Of the paternal orphans, 34.2% of the street children reported that their fathers are alive and 17.8% were not sure whether their fathers are alive or deceased. The majority of the street children (40%) stated their fathers were deceased. Pradhan and Sahoo (2022) and Adaugo et al. (2020) indicated similarities in their studies conducted in India and Nigeria respectively. This indicates that paternal and maternal orphanhood were among the causal factors driving children to live on the street environment.

Risks experienced by street children

This study found that street children encountered various risks in trying to meet their needs within the street environment, which has a detrimental impact on their well-being. The section below elaborates on the risks faced by street children in the following domains: economic, physical, psychosocial and educational.

Theme 1: Economic risks and children 's livelihood strategies

Street children are highly vulnerable to extreme poverty. The findings indicated that they are involved in various activities earning a livelihood as a source of income. Below are the subheadings derived from this theme: livelihood strategies and accommodation.

Livelihood strategies

Street children engage in various economic activities to survive on the streets. These survivalist activities carried out on the streets are prohibited by municipal by-laws, so the relationship between street children and municipal officials is strained. The figures below show the activities carried out by street children to earn an income on the streets.

Figure 1 shows that 38.6% of street children survived on activities such as recycling, car washing, commercial sex work, baggage carrier and part-time jobs, and 30.2% stated they beg on the streets. 12.4% of street children were rank marshals (in the Zimbabwean context, these individuals control the movement of taxis at public taxi ranks), while 9.4% are vendors. 9.45% rely on donations/handouts.

Accommodation

Street children who took part in this study described the different places where they sleep at night. The table below shows numerous locations where street children stayed at night.

Figure 2 revealed that 42.1% of street children in "others" refer to places not mentioned above, while 15.3% sleep at the taxi rank. 13.4% of street children sleep on pavements, and 12.4% rent a place to sleep for the night. 11.4% sleep beneath the bridges and 5.4% sleep at the gas station.

Theme 2: Physical risks

The findings indicated that street children are exposed to multiple physical risks by living on the streets. Below are some of the risks relevant to this theme: access to food, access to sanitation and adverse health implications of living on the streets.

Access to food

Starvation and hunger are common among street children in Zimbabwe. This is primarily because they lack funds to purchase food. Most street children reported that they could not afford a balanced meal and had to work very hard to get one meal each day. The diagram below depicts how and where street children get their food regularly.

Figure 3 reveals that 27.2% of street children bought their food, 18.8% collect leftovers, 18.8% relied on handouts and 16.8% of the street children stated they received food from welfare and religious organisations such as the Methodist Church, the Anglican Church, Kwa Mai Zuva in Mbare and Streets Ahead. 11.9% of the street children do work for food, while 6.4% rely on soup kitchens.

Health implications of living on the streets

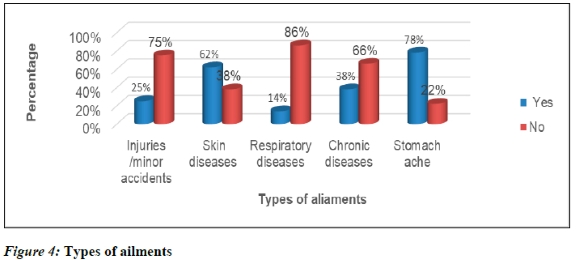

The street environment is hostile and exposes street children to various physical ailments. The illnesses that plague street children are indicated in the graph below.

Figure 4 above indicates that 78% of street children suffered from stomach aches. In addition, 62% of the sampled street children were affected by skin diseases. Furthermore, 38% of street children had chronic illnesses. In addition, 25% of street children had sustained injuries or been involved in minor accidents. Lastly, 14% of the street children had contracted respiratory diseases.

Sanitation

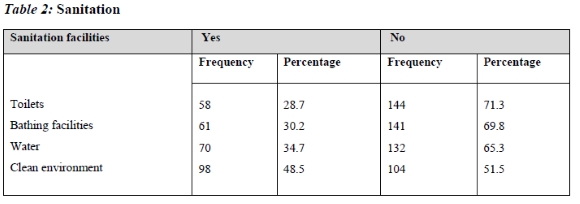

Because the street environment is toxic and polluted, making it unsafe for human survival, street children do not have access to proper sanitation. The table below indicates the difficulties street children face in maintaining proper basic hygiene.

Table 2 above reported that 71.3% of street children do not have access to toilets. Furthermore, 69.8% reported not having access to bathing facilities. In addition, 65.3% do not have access to water. 51.5% believed that there is no clean environment on the streets.

Theme 3: Psychosocial risks

The interaction of street children with each other on the streets influences their psychosocial well-being. The following sub-themes were derived from the main theme: criminal offences and antisocial behaviour.

Criminal offences

The street environment is volatile and exposes street children to various criminal offences. For example, they commit crimes under the influence of their peers and gangster groups or as a survival economic strategy to earn an income. Table 3 indicates the criminal offences that street children admitted having committed on the street.

Table 3 reported that 56% of street children were involved in economic offences and 17.5% were arrested for substance use. In addition, 14% were arrested for aggressive behaviour and 7.5% were detained for a sexual offence. Lastly, 5% were arrested for minor offences.

Antisocial behaviour

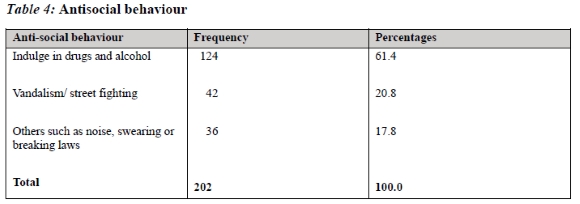

The norms and values of the streets influence the behaviour of street children. In this study, street children revealed that they are affiliated with different street-gang groups. Those gang groups directly influenced the behaviour of street children. The graph below shows antisocial behaviours of street children.

Table 4 above indicates that 61.4% of street children indulged in drugs or alcohol use, while 20.8% of the sampled street children were involved in vandalism / street fighting. 17.8% of the street children were involved in other activities such as noise, swearing or breaking laws.

Theme 4: Educational risks

Street children live or spend most of their time on the streets, which is not conducive to being encouraged to enrol in a formal schooling system. The sub-theme school dropout was derived from this theme.

Table 5 indicates that 50.5% of street children dropped out at the primary level, 36.1% dropped out at the pre-school level, and 13.4% dropped out at the secondary level.

DISCUSSION OF RISKS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The findings indicated that street children experienced risks to their physical health, such as bouts of diarrhoea, that impacted on their well-being. Some of the challenges reported in the findings include lack of access to adequate food to keep their bodies healthy. These findings correspond to those by Pratibha and Mathur (2016), who also found that street children in India do not have a balanced diet and this affects their physical well-being. Therefore, street children are susceptible to various deficiency ailments such as kwashiorkor and infections, which made their bodies weak and slow to recover from such ailments.

The findings of the study revealed that street children experience various physical illnesses such as respiratory illnesses, skin diseases, minor injuries, chronic diseases and stomach aches. These findings are congruent with those of Kabonga (2020), who found that the nature of their livelihood activities and unhealthy lifestyles in Iran makes street children vulnerable to physical illness. This demonstrates that the street environment inflicts harm on street children because variables beyond their control impair their physical development.

The lack of housing was reported in the findings as having a detrimental impact on all aspects of a child's development, since they are exposed to various environmental challenges, land and water pollution, and abuse on the streets. These findings corroborate those in the study of Chitiyo (2017), which revealed that street children's psycho-social well-being is affected because they do not have a permanent and safe place to sleep at night. The ESA posits that the family is regarded as the child's primary social group, which is responsible for meeting the basic needs of the child (Paquette & Ryan, 2009). Therefore, the lack of accommodation accounts for many of the challenges confronting children on the streets.

The analysis of the data revealed that street children do not have access to proper sanitation such as a clean environment, bathing facilities, safe water and toilets, which are vital for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. These findings are congruent with those of Maepa (2018), who claimed that corruption, lack of efficiency, poor management of finances and bureaucracy in public state entities severely affect street children, who lack access to safe drinking water and public restrooms. Contrary to the arguments presented above, Grineski (2014) states that homeless children and families are accustomed to street life; hence, despite government initiatives to build several decent forms of accommodation to meet their right to housing and proper sanitation, they still roam the streets. The ESA posits that the environment has a significant impact on child development. This suggests that a lack of basic sanitation leads to poor personal hygiene and exposes street children to illnesses that impair their physical growth and development.

A review of the study findings shows that street children face economic risks in the street environment. To survive, they require income to meet their needs, which motivates them to embark on various economic activities - legal or illegal - on the streets. A study done in Bangladesh by Reza and Bromfield (2019) revealed that economic activities play a crucial role in the well-being of street children. This statement reflects the degree of effort made by street children to make a living in the street environment compared to those living in a stable family environment. Krishnan (2010) explains that the environment plays a vital role in child development, either directly or implicitly. As a result, the economic activities conducted by street children affect their physical development as they do not have sufficient time to rest and recover. Therefore, social work practice in Zimbabwe should enrol older street children between 16 and 18 years in skills development and entrepreneurship programmes so that they can embark on sustainable livelihoods. Furthermore, those street children below 10 years of age should be removed from the streets and placed in children's homes (Ndlovu & Tigere, 2020).

The interactions of street children in the street environment has also been reported to affect their psychosocial well-being negatively. This is because street children lack the means to meet their fundamental needs, which drives them to engage in criminal activities. The criminal offences committed by street children are motivated by peer pressure and a need to survive on the streets. Top economic offences are petty crimes and robbery because of the need to obtain some income. These findings are in line with those of Jakaza and Nyoni (2018), who found that there is a link between criminal offences and the need to survive in the street environment. According to Bronfenbrenner (1994), micro- and mesosystems play an important role in enhancing child development. Hence the failure of the systems to satisfy fundamental needs drives street children into committing criminal activities.

Street children, as noted in the analysis of the data, also exhibit antisocial behaviours emanating from peer influence. These findings confirm those by Chikanda and Tawodzera (2017), who observed that peer pressure forces minor street children to engage in antisocial behaviour and criminal activities, because of the need to be accepted by their older peers on the street. Furthermore, failure to fit in with other peers can also lead to different sorts of abuse, including physical violence and confiscation of personal belongings such as clothing, money and food (Maepa, 2021).

Education is important in enhancing children's well-being. The findings indicated that street children's lack of access to formal education hinders their attainment of a higher social and economic status in life. Ashraf et al. (2022) note that poverty is inevitable among street children, because they lack fundamental social services such as education and health care, vital to attaining a better living standard. The mesosystem of the ESA highlights the importance of schooling in child development. Therefore, street children are at risk because they lack formal socialisation and education, which could bring them better economic opportunities.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The study's recommendations are derived from the findings and are intended to address the challenges faced by street children. This study recommends that Social Welfare Officers at DSD should implement policies that comprehensively seek to assess the challenges facing street children in Zimbabwe. This will allow the needs and challenges faced by street children to be addressed holistically. Social Welfare Officers need to implement family reunification and tracing programmes for street children who reported that their biological parents are still alive. Furthermore, they should provide therapeutic interventions so that children can be reintegrated into their families. This study recommends that children who are regarded as orphans be placed in institutional and foster care facilities to minimise the detrimental impacts of being exposed to hostile street environments that may adversely affect their development and growth. This study further recommends the establishment of contact centres around metropolitan cities in Zimbabwe. These contact centres will allow street children to obtain social welfare assistance such as counselling services, accommodation, food and clothing. Lastly, this study recommends that the DSD provide referrals to street children so that other welfare organisations can assist with the process of institutionalisation and provide basic necessities to vulnerable children.

CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this study was to assess the well-being of street children using the ecological systems approach. The conclusions derived from this study were drawn from the quantitative data collected from street children through a survey questionnaire in Harare Metropolitan Province, Zimbabwe. This study was unique, since little information is available about how the street environment affects the well-being of street children in Zimbabwe. This study highlighted the risks faced by street children.

The findings have shown that street children encounter economic, social, physical and psychosocial risks on the streets. The economic risks are forcing street children to indulge in various livelihood strategies such as vending, begging and marshalling vehicles to mention just a few. Street children work every day to earn a basic income and this affects their physical health as they do not have time to rest and recover. Regarding the educational risks, the findings indicated that a large number of street children dropped out of formal schooling. This affects their future prospects, because they have very few chances of being employed formally without any qualifications.

The findings indicated that street children face numerous physical risks such as limited access to proper food or sanitation, including basic health facilities, and are exposed to different types of ailments on the streets. These risks affect the physical well-being of street children. Street children also face psycho-social risks such as antisocial behaviour and are drawn into committing criminal offences. Such risks encountered by street children affect all facets of their lives and this increases or even entrenches child poverty and prevents them from reaching their full potential in life. This study has shown the critical importance of understanding the influence of the environment on child well-being.

REFERENCES

Adaugo, O., Ibadin, O. M., Ofovwe, E. G. &Abiodun, O. P. 2020. Street children in Benin City, Nigeria: Nutritional status, physical characteristics and their determinants. Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Research, 19(1):33-42. [ Links ]

Alex-Petersen, J., Lundborg, P. & Rooth, D. O. 2022. Long-term effects of childhood nutrition: Evidence from a school lunch reform. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(2): 876-908. [ Links ]

Ashraf, A., Ibrar, M. & Ullah, F. 2022. A qualitative exploration of street children life in Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the light of Urie Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory. Progressive Research Journal of Arts & Humanities (PRJAH), 4(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1986. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6):723-742. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In: Husen, T. & Postlethwaite, T. N. (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, P. A. 1998. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon, W. & Lerner, R. M. (eds.). Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

Chikanda, A. & Tawodzera, G. 2017. Informal entrepreneurship and informal cross-border trade between Zimbabwe and South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP) Migration Policy Series (74). Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Chitiyo, R. A. 2017. Street kids: A different face of childhood in Zimbabwe. [Online] Available: https://www.childhoodexplorer.org/street-kids-a-different-face-of-childhood-in-zimbabwe [Accessed: 18/11/2022]. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. 2018. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. California: SAGE. [ Links ]

Grineski, S. 2014. The multi-dimensional lives of children who are homeless. Current Issues in Education, 5(3):203-217. [ Links ]

Gunhidzirai, C. & Tanga, P. T. 2020. Implementation of government social protection programmes in mitigating the challenges faced by street children in Zimbabwe. Gender and Behaviour, 18(3): 16269-16280. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch, 2006. What future? Street children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. [Online] Available: https://www.hrw.org/report/2006/04/04/what-future/street-children-democratic-republic-congo/ [Accessed: 13/11/2021]. [ Links ]

Jakaza, T. N. & Nyoni, C. 2018. Emerging dynamics of substance abuse among street children in Zimbabwe. A case of Harare central business district. African Journal of Social Work, 8(2): 63-70. [ Links ]

Kabonga, I. 2020, Reflections on the 'Zimbabwean crisis 2000-2008' and the survival strategies: The sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) analysis. Africa Review, 12(2): 192-212. [ Links ]

Kanjanga, O. & Chiparange, G. V. 2015. Street kids in the Christian world: A case of Mutare urban-Zimbabwe. European Scientific Journal, 11(29): 301-317. [ Links ]

Kaseke, E. 2011. The poor laws, colonialism and social welfare: Social assistance in Zimbabwe. In: Midgley, J. & Piachaud, D. (eds). Colonialism and welfare: Social policy and the British Imperial Legacy. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Kothari, C. R. 2004. Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Delhi: New Age International. [ Links ]

Krishnan, V. 2010. Early child development: A conceptual model. [Online] Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/study/Early-Child-Development%3A-A-Conceptual-Model*-Krishnan/80996bed2ef51e4128e5251f98242009888f4028 [Accessed: 02/11/2021]. [ Links ]

Landau, S. & Everitt, B. S. 2004. A handbook of statistical analyses using SPSS. New York: Chapman & Hall/ CRC. [ Links ]

Leedy, D. P. & Ormrod, E. J. 2013. Practical research: Planning and design. 10th ed. Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Maepa, M. P. 2021. Self-esteem and resilience differences among street children compared to non- street children in Limpopo Province of South Africa: A baseline study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9: 1-7. [ Links ]

Maree, K. 2007. First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Mhizha, S. 2010. The self -image of adolescent street children in Harare. Master's thesis. University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. [ Links ]

Neuman, L. W. 2014. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 7th ed. Essex: Pearson. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, E. & Tigere, R. 2022. Life in the streets, children speak out: A case of Harare metropolitan, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities in Research, 5(1): 25-45. [ Links ]

Ogan, E. P. 2021. Dynamics of street children in Africa. [Online] Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348539465_DYNAMICS_OF_STREET_CHILDREN_IN_AFRICA [Accessed: 13/11/2021]. [ Links ]

Ogutu, M. 2020. Under the bridge: The invisible lives of street children. [Online] Available: https://www.mandelarhodes.org/ideas/under-the-bridge-the-invisible-lives-of-street-children/ [Accessed: 08/11/2021]. [ Links ]

Paquett, D. & Ryan, J. 2009. Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory. [Online] Available https://www.semanticscholar.org/study/Bronfenbrenner's-Ecological-Systems-TheoryPaquetteRyan/b23a4e916f3d815a2624f2289575cdf5c493a0c6 [Accessed: 10/10/2021]. [ Links ]

Patel, L., Pillay, J., Henning, E., Telukdaries, A., Norris, S., Graham, L., Haffejee, S., Sani, T., Ntshingila, N., Du-Plessis Faurie, A.,Wanga, Z. M., Baldry, K., Sello, M., Mbowa, S., Setlhare-Kajee, R., Bezuidenhout, H. & Rhamasodi, R. 2021. Community of practice for social systems strengthening to improve child -well-being outcome. findings from Wace 1: Tracking child wellbeing. [Online] Available: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/5851/file/ZAF-Community-practice-social-systems-stregnthening-improve-child-wellbeing-findings-1-wave-Oct-2021.pdf [Accessed: 25/12/2021]. [ Links ]

Pratibha, A. & Mathur, A. 2016. Difficulties and problems of street children. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(2): 1859-1861. [ Links ]

Republic of Zimbabwe. 2014. Zimbabwe agenda for sustainable socio-economic transformation (ZIMASSET). [Online] Available: https://www.dpcorp.co.zw/assets/zim-asset.pdf/ [Accessed: 11/10/2021]. [ Links ]

Reza, M. H. & Bromfield, N. F. 2019. Poverty, vulnerability and everyday resilience: How Bangladeshi Street children manage economic challenges through financial transactions on the streets. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(5): 1105-1123. [ Links ]

Rubin, A. & Babbie, E. 2013. Essential research methods for social work. 3rd ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Salihu, H. B. 2019. The growing phenomenon of street children in Tehran: An empirical analysis. Journal of Social Science, 3(1): 1-10. [ Links ]

Siporin, J. 1980. Ecological systems theory in social work. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 7(4): 507-532. [ Links ]

Sirgy, M. J. & Lee, D. J. 2018. The psychology of life balance. In: Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. (eds.). Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers. [ Links ]

Thor, T. P. S. 2016. An ecological approach to understanding highly able students' experiences of their academic talent development in a Singapore school.[Online] Available: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1534486/1/EdD%20Thesis_THOR%20T.P.S.pdf [Accessed: 09/10/2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2003. Hope never dries up: Facing the challenges. A situational assessment analysis of children in Zimbabwe in 2002. Harare: UNICEF. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) 2010. Evaluation of programme of support for national action plan for orphans and vulnerable children impact/ outcome assessment. Harare: UNICEF. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2015. Introduction to the human rights-based approach: A guide for Finnish NGOs and their partners: Finland. [Online] Available: https://unicef.studio.crasman.fi/pub/public/pdf/HRBA_manuaali_FINAL_pdf_small2.pdf [Accessed: 15/10/2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 2017. Children in the street. The Palestine case. [Online] Available: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/864C6E78862058D9492572D600052C95-Full_Report.pdf [Accessed: 02/11/2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) & Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare. 2016. Social protection budget brief. Harare: UNICEF Zimbabwe. [Online] Available: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/6511/file/UNICEF-Zimbabwe-2020-Social-Protection-Budget-Brief.pdf [Accessed: 12/10/2021]. [ Links ]

Article received: 15/8/2022

Article accepted: 11/5/2023