Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.59 n.4 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/59-4-1167

ARTICLES

Effects of family preservation services on family cohesion: views of family heads

Zibonele ZimbaI; Pius TangaII; Zintle NtshongwanaIII

IUniversity of Johannesburg, Department of Social Work and Community Development, Johannesburg, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2597-2167 zibonelez@uj.ac.za

IIUniversity of Fort Hare, Department of Social Work/Social Development, Alice, South Africa https://orcid/org/0000-0003-1359-8729 ptanga@ufh.ac.za

IIIUniversity of the Witwatersrand, Department of Social Work, Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4305-6402 Zintle.ntshongwana@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Family preservation services are considered essential and allow children to be with their families, which by implication, avoids their placement outside family care. This article presents the views of family heads on the effects of family preservation services, such as time spent together and connectedness. The findings of the study emerged from the qualitative approach, which entailed conducting semi-structured interviews with 20 family heads. Adverse circumstances such as travelling distances, lack of communication from professionals and fear of communal judgement faced by families during family preservation services are also addressed. The study nevertheless concludes that family preservation services are a mechanism to rebuild families.

Keywords: Child protection services; family; family cohesion; family preservation services; social work

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this study was to investigate the views of family heads on the impact of family preservation services on family cohesion in South Africa. The White Paper on Families in South Africa (Republic of South Africa [RSA] 2013) defines family preservation services as services that focus on family resilience in order to strengthen families in order to keep them together as far as possible. Family preservation is also considered as a planning process that addresses the imminent risks facing children and parents by empowering families and rendering the necessary support services to restore family functioning to protect and care for their children (Strydom, 2010; Strydom, Spolander, Engelbrecht & Martin, 2017). According to Strydom (2012), family preservation is an approach used by social workers to provide social work services to both the child and the family in cases where child maltreatment is reported to child welfare services such as intensive family preservation services, family-centred services and family support services. Therefore, family preservation is an integral part of child protection. Child protection services have been defined as "certain formal and informal structures, functions, and capacities that have been assembled to prevent and respond to violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation of children" (RSA, 2013; Strydom, Schiller & Orme, 2020; United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Save The Children & World Vision, 2012).

Child protection services are broadly categorised under three types - namely primary prevention, secondary prevention and tertiary response. Focusing on primary prevention are universal services directed at the general population with the aim of stopping violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation, ideally before it occurs. The purpose of primary prevention activities is to raise awareness and to engage and empower households and communities, service providers, practitioners, professionals and duty bearers to stop and address violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation (United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Save The Children & World Vision, 2012). Primary prevention activities provided to families in child protection services in South Africa include educational services on child abuse, educational parenting skills, and family communication activities. Child protection services enable vulnerable families to explore possibilities of working together as families to create a bond referred to as family cohesion. Family cohesion encompasses the emotional bonding between family members as well as regulating the degree of autonomy experienced by individuals within the family system (Olson, Sprenkle & Russell, 1983).

Numerous studies (Combrinck, 2015; Nhedzi & Makofane, 2015; Nzuza, 2019; Strydom, 2012) have been conducted in the field of family preservation and child protection services on different types of family preservation services, the role of social workers in the planning and implementation of family preservation services, and the experiences of social workers in the provision of family preservation services. However, no study has been conducted specifically to understand the effects of family preservation services on family cohesion, nor on the factors that impede the participation of families in preservation services provided by social workers. Hence the focus of this study is on the views of family heads on the effectiveness of family preservation services in achieving family cohesion.

The article is organised as follows. First, the article provides a statement of the problem. Secondly, it presents a literature review with a focus on the conceptualisation of the notion of family, before the focus shifts to providing different types of family preservation services in South Africa. Thirdly, the article addresses issues of crisis intervention and the strengths perspective. The article ends with a discussion of the findings before offering a conclusion and making recommendations.

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Family preservation services in South Africa is a vast field with numerous focus areas. EbscoHost Discovery provided access to multiple databases, including Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, BASE, Complementary Index, Directory of Open Access Journals, PubMed, SocINDEX with Full Text, Science Direct, Social Sciences Citation Index and Supplemental Index; the literature consulted focused mostly on challenges encountered by families and social workers (Nhedzi, 2014; Proudlock & Jamieson, 2014). Other prominent studies (Nhedzi & Makofane, 2015; Strydom, 2010; Strydom, 2012; Thoburn, Robinson, & Anderson, 2012; van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016) focus on the role and views of social workers in the provision of family preservation. According to the Children's Act 38 of 2005 Section 148 (1)(b) (RSA, 2006), child protection services include services relating to early intervention services in which a court may order the child's family and the child to participate in prescribed family preservation services. Several studies in the United Kingdom reported on the effectiveness of family preservation (Fraser, Nelson & Rivard, 1997) as well as on challenges of family preservation (Fraser et al., 1997; Heneghan, Horwitz & Leventhal, 1996; Hooper-Briar, Broussard, Ronnau & Sallee, 1995; O'Reilly, Wilkes, Luck & Jackson, 2009). In South Africa studies by Nhedzi (2014) and Strydom (2012) looked at the effectiveness of preservation in families and the experiences of the social workers involved. However, as far as we could establish, no study has been conducted to investigate the effects of family preservation services specifically on family cohesion in South Africa. The focus on the effects of family cohesion is vital in order to understand the value of family preservation on the emotional bonding of family members with one another. Therefore, this study seeks to gain in-depth understanding of the views of family heads on the impact of family preservation services. The article is anticipated to contribute to the dissemination of knowledge for practice with respect to the value of family preservation in maintaining family cohesion.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In South Africa the largest sphere of service rendering in social work is child and family welfare, which is designated by legislation to provide child protection services. Child protection services are aimed at reducing child abuse and neglect, whilst protecting the child and preserving the family unit (RSA, 1997). Katz and Hetherington (2006) submit that child protection services focus on family-centred interventions, which are referred to in the literature as "family support services" and "family preservation services". The Children's Act 38 of 2005 Section 46 (g) (RSA, 2006) considers family preservation services as prevention and early intervention services. Section 157 of the Act further stipulates that caregivers or parents must obtain a report from a designated social worker about the details of family preservation services that have been tried. Therefore, the first step in understand their impact is to conceptualise family and family cohesion. The second is to unpack family preservation from two perspectives - family preservation services as prevention and early intervention services, and to discuss family preservation as a statutory intervention service. The relevant steps are outlined below.

Conceptualisation of the family and family cohesion

The word "family" triggers thoughts of parents with their children. However, the concept has been redefined a countless number of times. The Department of Social Development's National Policy Framework on Families (DSD, 2001) defines family as individuals who either by contract and/or agreement, or by descent and/or adoption, have psychological/emotional ties with each other, and function as a unit in a social and/or economic system but who do not necessarily live together intimately. Lanz and Tagliabue (2014) state that families are believed to share certain features such as being intimate and interdependent, stable over time, and set off from other groups by boundaries related to the family group and promoting supportive tasks. The Department of Social Development (DSD, 2008:16) points to:

the multicultural and dynamic nature of the South African society, and defines family as a group of persons united by ties of marriage, blood, adoption or cohabitation, characterised by a common residence, interacting and communicating with one another in their respective family roles, maintaining a common culture and governed by family rules.

A family can also be considered in the context of nuclear families, extended families, single-parent families as well as in terms of matrilineal, patrilineal, fictive, residential and non-residential forms (McGoldrick, Carter & Garcia-Preto, 2011). A family is considered to be an important environment for an individual's healthy development (Miller et al., 2000).

Family cohesion has been defined with reference to the emotional bonding that family members have towards one another (Olson, Russell, & Sprenkle, 1983). Olson, Portner and Bell (1982) argue that family cohesion manifests in the emotional bonding between family members and the degree of autonomy experienced by individuals within the family system. Jhang's (2017) study has shown that family cohesion can alleviate the individual psychological problems contributing to mental health issues. The higher the family cohesion, the more support and help the individual can get from others, which can in turn help the individual reduce the negative effects of stress (Zeng, Ye, Zhang, & Yang, 2021).

Family preservation services as prevention and early intervention services

According to Strydom (2012), the family preservation approach is the main model used by social workers to provide social work services to both the child and the family in cases where child maltreatment is reported to child welfare services. The main purpose of a family preservation programme is to assist families in creating healthy and safe home environments where children's needs could be met (Proctor & Dubowtiz, 2014). Most preservation programmes have certain basic core characteristics in common such as providing families with concrete assistance at the initiation of the services, and developing a service plan to address the most pressing stressors that have a potential to contribute to child maltreatment (Rodriguez-Jenkins & Marcenko, 2014). The services provided by family preservation programmes are mostly short-term and intense, and involve the making of many contacts in the natural environment of the family's home (Strydom, 2012). Child protection services in South Africa follow the family preservation approach in which attempts are made to keep the child safe in the home by addressing the causes of abuse whilst working with the family as active participants (Malatjie & Dube, 2017; Strydom, 2012; Swart, 2017; Tully, 2016). These services are provided within a continuum of care, which consists of prevention services, early intervention services and statutory services, when necessary (Swart, 2017). These services are regarded as prevention services, aimed at the larger population, to prevent child abuse by raising awareness not only of the issue but also the available community resources to address it (Makoae, Roberts & Ward, 2012; Swart, 2017). Early intervention services include developmental and therapeutic interventions aimed at specific families that are at risk of statutory intervention because maltreatment has already occurred (van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016). Statutory intervention, which entails a child being placed in foster care, only occurs once the other two service levels have proved unsuccessful in ensuring the safety of the child (Swart, 2017). Hence, rendering these services allows families to realise their strengths and inherent capacity to continue to support, care and protect their children within the family system (Combrinck, 2015; Dhludhlu & Lombard, 2017; van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016).

According to Strydom (2010), focusing on family preservation services can reduce the number of children entering deeper into the statutory system, whilst allowing families to realise their inherent capacity to protect, care for and support their children. In addition, providing intensive family preservation services helps families to work with other people in addressing dangers that risk the removal of a child from the family. Mosoma and Spies (2016) assert that intensive family preservation services aim at helping families at risk, in an unsafe situation, or who are at risk of being separated from their children because of unpleasant circumstances, or who have been separated from their families and placed outside their family home. Strydom (2012) emphasises the importance of rendering preventive services to families prior to the onset of crisis to limit the possibility of families entering into the welfare system and to minimise the need for statutory services.

This means that family preservation services are both representative and therapeutic interventions rendered by social workers to preserve the family and to prevent the removal of children to alternative care (Strydom, 2012). These services aim at strengthening the family's capacity and providing them with access to formal and informal resources. Van Huyssteen and Strydom (2016) describe family preservation services as early intervention child protection services aimed at preventing the abuse, neglect and abandonment of children. The focus of the programme is on identifying strengths of families and to keep them intact as far as possible (Mosoma, 2014). Similarly, Strydom (2010) argues that family preservation services are provided to families for the purpose of increasing and extending the capacity of parents to care for and protect their children or families, so that children can undergo the desired development. Strydom et al. (2017) strongly stress that the family preservation approach is closely linked with the development approach; hence, the focus is on prevention and early intervention services that support children and families.

The social development approach to enhance the welfare of citizens embraces services that aim at supporting and empowering families to use community services to meet their socio-economic needs (Ntjana, 2014; Sesane & Geyer, 2017; Strydom et al., 2017).

Family preservation services as statutory intervention services

In South Africa, family preservation services are also supported by the Constitution (RSA, 1996). For instance, Section 28 states that every child has a right to family care or parental care, or to appropriate alternative care when removed from the family environment. This indicates that the Constitution, which is the supreme law of the land, protects the dignity and rights of all, and regards families as an important institution for childcare and protection. Therefore, measures should be taken to ensure that children in need of care are protected within their environment. This is in agreement with statutory intervention services as stipulated by the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2006). Moreover, statutory intervention is outlined by Sections 150-151, which state the conditions under which children in harmful circumstances are or may be considered to be in need of care and protection, and provide for the statutory removal of children to alternative care. In addition, Section 153 of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 provides for perpetrators of child abuse to be removed from the home instead of ordering the removal of the child. Based on these sections, amongst several other provisions, a family member or family members may be ordered to attend a family preservation programme (DSD 2008; RSA, 2006, Section 46). Furthermore, these services are provided as statutory intervention services rendered to families waiting for the outcome of court procedures after the statutory removal of a family member (the child or the perpetrator) from home (DSD, 2008; DSD, 2012). Once the order is granted by a Children's Court, social workers should activate aftercare services. Aftercare family preservation services are provided to families of children who have been statutorily removed from their homes to alternative care (White Paper on Families in South Africa, 2012). This is done to address the risk factors that necessitated the removal of a child or family member, and to facilitate the development of a stable, self-reliant and well-functioning family (DSD, 2011; DSD, 2012; RSA, 2013). Thus, children who have been separated from their families are reintegrated into the family and communal life through the provision of services that seek to restore family functioning, such as behavioural modification programmes and family counselling (DSD, 2008; DSD, 2012).

Considering the conceptualisation of family preservation as both prevention and early intervention services, and as statutory intervention services, the importance of role of family preservation services is clear. Family preservation services are also seen as legislative interventions to address the risks of family dissolution. However, the concept of family preservation is not engaged through literature and policy framework on its significance to promote closeness and family functioning skills that increase prospects of family cohesion.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study proceeded from two points of departure, namely the crisis intervention perspective and the strengths perspective. The former is rooted in the understanding that the perspective represents an attempt to empower an individual who is undergoing a crisis by helping them to find viable solutions that can help ameliorate the problems causing extreme tension and stress. In this study, crisis intervention perspective was selected to understand how family heads and their families developed coping strategies to preserve the cohesion of their family. Since the crisis intervention perspective focuses on advancing the empowerment of individuals, it does not focus specifically on the strengths of individuals. Therefore, the strengths perspective is used in the study to highlight the strengths and resources of family heads and their environments, rather than on their problems and pathologies during the rendering of family preservation services.

Crisis intervention perspective

A crisis is a state which is the result of an event or series of events that pose a threat, or lead to a loss or challenge which an individual struggles to cope with using their habitual coping strategies or strengths (Coulshed & Orme, 2012). From a crisis intervention point of view, the provision of family preservation services seeks to stabilise the crisis situation that could cause children in need of care and protection to be removed from their families (Strydom, 2010). The key assumption is that services are home-based and are rendered for a short period of time to ensure that children who are involved remain safe (Berry, Cash, & Brook, 2000). The focus is on the provision of mechanisms to enable a family with problems to cope. The theory supports the assumption that a family must be provided with the appropriate coping skills to achieve stability during the crisis. Therefore, in this study a family is viewed to be in crisis in terms of the theory, and the services provided by the social workers are intended to assist the family to deal with their crisis within a given time frame. However, the assistance provided in terms of this perspective does not necessarily address the individual strengths of members in the family; hence, the use of the strengths perspective to complement the crisis intervention perspective was necessary.

Strengths perspective

The strengths perspective posits that parents can consolidate their strengths to be able to take care of their own children with the necessary support from social workers (Saleebey, 2013). From a crisis intervention perspective, establishing a collaborative relationship in assessing the family's strengths and drawing up an intervention plan that seeks to protect a family member who is at risk might be impractical (Higham, 2006). The collaborative relationship ensures that social workers are attentive to clients' strengths during the intervention process (Sheafor, Horejsi, & Horejsi, 2000). Saleebey (2013) identifies a number of basic assumptions of this practice framework: (1) every individual, group, family and community has strengths; (2) trauma, abuse, illness and struggle may be harmful, but may also be sources of challenges and opportunities; and (3) the environment in which the client lives and functions is full of resources. Therefore, this approach presumes that all individuals and groups have overlooked and untapped reserves of abilities, fortitude, goodwill, knowledge, experiences and other assets. If these strengths are recognised and used in the helping process, they elevate the client's motivation and enhance the possibility for change. The contention in family preservation services is that the crisis intervention and strengths perspectives are applicable to assist families to gain control and (re-)establish family cohesion.

METHODOLOGY

This article is based on a larger study conducted in Amathole District Municipality, which is situated in the central part of the Eastern Cape of South Africa, and is comprised of six local municipalities, namely Mbhashe, Mnquma, Great Kei, Amahlathi, Ngqushwa and Raymond Mhlaba. In this exploratory qualitative study, 20 heads of families who were primary care givers represented their families; during the data collection they were asked to reflect on the effects of family preservation services on family cohesion and family functioning. The study used the following criteria to select the participants:

• A head of a family (a person over the age of 18, who provides for a family and looks after the functioning of the family);

• Resides in the Amathole District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province; and

• Received the following family preservation services:

1. Intensive family preservation services, and

2. Family support services.

The recruitment process was undertaken as follows. First, 10 child welfare and family organisations were approached with a letter of request to access data from families that met the requirements of the study. Once the gatekeepers had granted permission to engage social workers to help in the selection of heads of families, social workers were contacted and asked to purposefully identify families in their caseloads that met the requirements of the study. Secondly, social workers shared the information letter with the heads of the families so that they could understand the nature and purpose of the study before deciding to participate. The information letter about the study included contact details of the researcher which heads of families who were interested in the study used to make contact with the researcher. Afterwards, the process of data collection commenced with 20 heads of families. An in-depth interview technique was used to collect the data; an interview guide was formulated taking into account the objectives of the study. Semi-structured interviews allowed participants the freedom to digress and to introduce their own issues during the interviews.

Thematic analysis was used to process the collected data, which were scanned, transcribed, arranged and organised. This was done to identify incomplete, inaccurate, inconsistent and irrelevant data in order to organise the material collected into relevant categories. Data were organised into a manageable format and into groups in terms of descriptions, common words, phrases, themes or patterns of information (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Tabulation was the best format for presenting the data in ways that allowed for meaningful summaries and interpretations. Excerpts were also considered to be useful in presenting feedback from the face-to-face interviews.

Steps recommended by Creswell (2009) were followed to transcribe all the audio-recorded responses verbatim from the semi-structured interviews. The researchers listened to the audiotapes, and read and re-read all the transcriptions. Significant statements pertaining to participants' experiences were extracted; a list of topics was compiled and similar topics were clustered together. The most descriptive words for the topics were assigned and turned into categories. Afterwards, statements were organised into themes and sub-themes in order to provide full descriptions of participants' experiences.

To ensure rigour and trustworthiness of the study, four critical components of trustworthiness, namely credibility, transferability, confirmability and dependability were used. Credibility was enhanced by ensuring that the participants met the criteria for inclusion in the study. Transferability was promoted by checking whether the research findings could be generalised or transferred to other settings. Confirmability was ensured through an audit trail of the recorded and transcribed data. The dependability of the study was ensured by providing narratives in support of all themes and subthemes presented.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

The researchers acknowledge the following limitations:

• The study only collected data from family heads, whose views may not be representative of the views of entire families;

• The sample size of the study was 20 family heads, and the study findings can thus not be generalised; and

• The target population of the study included only family heads; thus, the findings reflect their views only. The study could have benefited by incorporating the views of social workers on the impact of family preservation services on family cohesion.

FINDINGS OF THE STUDY

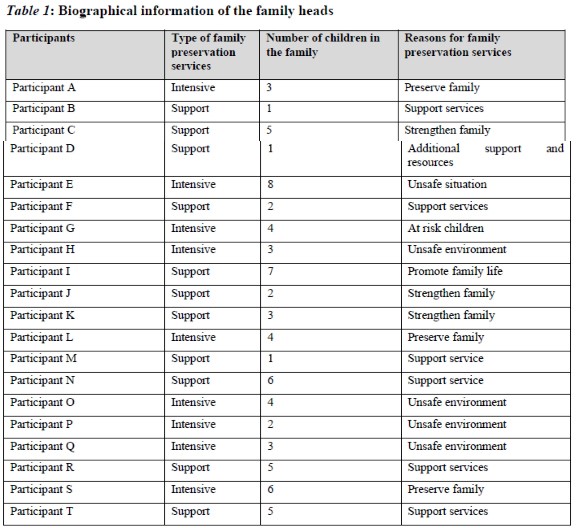

This section is divided into two parts. The first part provides the biographical information of the family heads, and the second presents the themes and sub-themes that emerged from the narratives of the participants, whose verbatim comments are italicised and indented. The confidentiality and anonymity of the study participants has been protected.

Eleven of the family heads who participated in the study indicated that they were receiving support services for family preservation, whilst the remaining nine said that the type of family preservation services they were receiving included intensive family preservation services. The findings of the study are consistent with those by Strydom (2012), which found different types of services rendered by social workers to at-risk families, including types of family preservation services such as intensive family preservation, family support services and family-centred services. About sixteen of the family heads who participated in the study indicated having between 1 and 5 children each. Four of them indicated that they had between 5 and 8 children. The findings of the study with the report issued by O'Neill (2023), which indicates that the fertility rate in South Africa is 2.4 children per woman. About six family heads indicated that the reason for receiving family preservation services was the need for support services. Five of them indicated that an unsafe environment/ situation was the reason they received family preservation services. The other family heads indicated that they received family preservation to preserve their family, promote family life and strengthen family functioning.

Theme 1: Effects of family preservation on family cohesion

Participants were asked to reflect on the effects of the family preservation service on family cohesion. The views of the majority of the family heads were grouped into four sub-themes as presented below:

Sub-theme 1: Time spent together

During the in-depth interviews, heads of families were adamant about their views on the value of the time spent together as a family since being involved in family preservation services. Almost all the heads of families stated that their families never spent time together. The reason behind this was due to harsh family approaches, as a form of discipline, when dealing with misbehaviour. Fearing the environment created by the harsh discipline approach prevented children from spending time with their parents or from being part of a family unit. However, a few of the heads of the families stated that they did spend time with their children, since the children were still at an age that made it easy to monitor and control them.

Participant D said:

My family never spends quality time together; we only see each other maybe when others are hungry or watching television.

Participant F stated that:

I spend time with my kids because they are young and controllable, I can tell them that we need to spend time as a family.

Sub-theme 2: Connectedness

Family heads indicated that family preservation services enable family members to feel connected to one another. They considered being involved, as families, with social workers in making decisions and discussing progress updates as factors that enhance connectedness. Participant K said:

I realised that since we started seeing social workers, we attend meetings to social workers together and we can always talk as family.

Sub-theme 3: Family joint tasks

Most of the family heads said that being part of family preservation services and being able to do tasks such as attending support groups and family events in the community gave them a sense of acting jointly as a family. Participant F said:

We attend to events together and get tasks during sessions and we do the tasks as a family like going to SASSA.

Sub-theme 4: Power negotiation

Family heads also revealed that receiving family preservation services improved the family's ability to make joint decisions and to negotiate power relationships in dealing with family issues. Family heads explained that before working with social workers on family preservation services, they were making all the decisions as heads without considering other family members.

In my family, I do not take decisions alone now; I consult with everyone if we must decide, but before only me took decisions in the family. (Participant B).

The findings above show that heads of families consider family preservation services valuable and as adding value to time spent together by the family, as well as enabling joint tasks, fostering connectedness and creating an environment for negotiating the power relationships within the family.

Theme 2: Adversities faced in participating in family preservation services

The second theme of the study dealt with the adversities faced by heads of families in participating in family preservation services. Six sub-themes emerged from this theme, namely travelling distance, lack of communication by officials, lack of support amongst family members, lack of full involvement of members in each other's lives, cultural beliefs, and fear of being judged. These sub-themes are discussed below.

Sub-theme 1: Travelling distance

Family heads indicated that as much as family preservation services add value to family cohesion, the main adversity faced was the location of social work organisations and departments. Family heads indicated that social work organisations and departments were often in town and this meant travelling to consult social workers. Organisations and government department offices are mostly situated in urban areas, whilst most users of these services reside in townships and rural areas. One family head emphasised this point as follows:

We stay in a village; we travel to meet social workers for family conferences. We cannot afford transporting all members of the family to the programmes designed for us by social workers (Participant G).

Sub-theme 2: Lack of communication by professionals

Communication is the most important ingredient in facilitating change and in showing support for families in family preservation services. Heads of families strongly indicated that lack of communication from social workers demotivated them from attending and committing to services that would benefit their families. Participant T maintained that:

We do not get constant communications from our social workers; we never get calls to check us up or update us of any progress we are making.

Sub-theme 3: Lack of support amongst family members

Some of the participants indicated that weak support amongst family members was a difficult and demotivating factor that resulted in their discontinuing participation in family preservation services. They asserted that family preservation services require family members to engage with each other and to do activities as a team, but it is often difficult to receive support from other family members. Another head of a family added emphatically that the support lacking is emotional, physical and psychological in nature. Participant T stated explicitly that:

In my family there is no support at all.

Participant M added:

My kids are not supportive at all, financially and emotionally.

Sub-theme 4: Lack offull involvement of members in each other's lives

Heads of families clearly pointed to lack of involvement of members in other family members' lives. They referred to the lack of full involvement of members in attending counselling or therapeutic services which were provided to their entire families. The level of family involvement in each member's life was indicated as being very poor. One of the family heads pointed out:

Me, my husband and my kids we [are] not involved in each other's lives or sharing anything about each other; sometimes they do things I do not know in their lives (Participant J).

Sub-theme 5: Cultural beliefs

Family heads pointed out that their cultural beliefs and worldviews created difficulties in terms of their participation in some of the family preservation services that are related to parenting skills and discipline. For example, the heads indicated that it was their cultural belief that a child must not say anything to their parents during or about their upbringing, yet in parenting skills training the children are encouraged to be involved in family processes. Participant J said:

I am a village person with beliefs in my culture that kids are kids and must be treated as such in terms of discipline and communication, but in parenting skills meetings we are encouraged not to hit our kids and try new ways to raise them; I have a problem with that as my kids are disrespectful.

Sub-theme 6: Fear of being judged

The participants indicated that another difficulty faced during family preservation services is fear by family members of being judged by others in the community. They were afraid of being regarded as people who needed social work services. Some family heads pointed out that asking for help or being offered help creates feelings of fear of being judged and stigmatised. Participant E said:

In my community, working with social workers there is a perception that you are too poor or a failure. People in my community just do not have to know the reason of working with social workers, they assume the worse and that makes me feel like they will judge me.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

Based on the views of the heads of families, family preservation services are seen as helping families to intentionally spend time together. McAuley, McKeown and Merriman (2012) found that spending time enables families to value one another as a family unit. The finding on the effect of family preservation services on family cohesion confirms that the services provided to families sometimes fulfil the purpose stipulated in the White Paper on Families in South Africa (RSA, 2013), which states that family preservation services must be provided to ensure improvement in family cohesion. From a strengths perspective, the effects of family preservation on families is linked to the services provided, and affect the way families view, perceive and experience services (Collins, Jordan, & Coleman, 2010; Saleebey, 2013). Based on the findings by McAuley et al. (2012) as well as those of the current study, in practice, family preservation services must been seen as a tool that facilitates time spent constructively amongst family members. Family preservation services should be viewed as a catalyst for the creation of opportunities for families to jointly confront family challenges.

The study revealed that being part of family preservation services encourages families to be connected to one another. Wells and Whittington (1993) conducted a comparative study between families receiving family preservation services and those not receiving these services to measure improvements in family functioning. They found an increased high level of connectedness in the former group compared to the latter. The findings of this study confirm that families that receive family preservation services experience improved family connectedness. Morris et al. (2022) found that practitioners of family preservation initiatives consider joint tasks as a catalyst for engagement, readiness, the development of a therapeutic relationship, and the need for supported closure. Dawson and Berry (2002) argue that engaging families in child welfare improves ways in which families view power relations amongst family members. This argument is aligned with the findings of the study that show that the involvement of families in family preservation services enables them to engage with and deconstruct power relationships and approach decision-making with a different mind-set. Combrinck (2015) claims that family preservation services create a sense of belonging and closeness amongst family members. The findings of this study indicate that family preservation services are vital in facilitating connectedness amongst family members. The findings, supported by the literature, further suggest that the provision of family preservation services can be used to promote family closeness and to empower families to enhance their ability to confront family issues as a unit.

The study found that family heads experience difficulties in the process of their involvement in family preservation services. Travelling distance is considered as an obstacle hindering attendance at family preservation-related activities. Wilson et al. (2020) argue that most families that receive family preservation services are located some distance away from the social services to which they need to travel for consultative purposes. The findings of the study resonate with the realities of South Africa in terms of the dispersed location of services. Most services required by marginalised individuals are located in the suburbs or in towns, as the apartheid-initiated by the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in the Natives Resettlement Act No.19 of 1954 (RSA, 1954) which had the effect of placing persons of colour some distance away from services institutions.

Kapur (2018) notes that lack of communication withy clients in social work practice may lead to demotivation among service users to fully utilise social work services needed by marginalised and vulnerable individuals, groups and communities. The findings of the study reveal that a lack of communication by professionals discourages families from taking part in programmes that benefit them. The findings further show that as much as family heads see value in family preservation services, the discipline approach in families contributes to the creation of feelings of not enjoying spending time together due to fear of being harshly punished in case of misbehaviour. The study does align itself with the views of Berger and Font (2015) and Nzuza (2019), who state that family preservation services provide families with an opportunity to learn and improve ways of spending time together through the assistance of social workers. Based on the findings of the study, family members are not offered enough time to work on relationships with each other and to understand the need to be involved in each other's lives.

The perceptions of the heads of families who participated in this study regarding the argument that social workers help families to improve skills on spending time together is validated by findings of Nhedzi and Makofane (2015), which indicated that social workers are significant in helping families to acquire skills essential for family functioning. Furthermore, it has been argued that in family preservation services, families start working towards spending quality time when an attempt is made to support the family to care and protect their children (Forrester, Kershaw, Moss & Hughes, 2008). The provision of family preservation services is expected to draw on the strengths of family members and to constantly encourage and support families' attempts to use new skills towards attaining that goal (Hurley et al., 2012). Hence, it is vital for social workers to continuously identify and utilise the family's support systems, knowledge, skills, values and strategies. The study revealed that family members were not supportive of each other. Even if one of them was going through a difficult time, they did not care.

Families seem to think that family preservation services do not provide their families with skills that ensure improvement in their support of each other. The findings also present evidence of the effects of family preservation services on family cohesion. Even though the study shows that a sense of closeness amongst family members cannot be confirmed, the strengths perspective indicates that every social worker needs to tap into the available resources when providing services to families (Saleebey, 2013). This facilitation of family members' support of each other is critical to unlock their capabilities.

The literature indicates that family members resist involvement in services provided for family preservation and show lack of cooperation, which negatively affects the provision of family preservation services (Coulshed & Orme, 2012; Sandoval, 2010; Strydom, 2010). Van Wert, Anreiter, Fallon & Sokolowski (2019) state that poverty is often linked with abuse and neglect, because of the stresses that people have to endure in their lives under these circumstances. Heads of families pointed out that the long travelling distance was one of the main reasons they did not fully participate in family preservation services. Beesley, Watts and Harrison (2018) assert that communication skills are some of the most important skills in social work practice. Communication is regarded as a crucial component in helping families build and maintain relationships for them to become functional (Galvin, Braithwaite, & Bylund, 2015). Similar to findings were presented by Nhedzi and Makofane (2015), whose study revealed that parents continue to have difficulties in maintaining good communication with their social workers. Effective communication is a major component of the social work profession. Heads of families can benefit and achieve better outcomes when social workers focus on building quality relationships with their clients (Lee & Ayon, 2004).

Nhedzi and Makofane (2015) found that certain African cultural issues can pose a challenge in social work practice when it comes to issues of child protection; this is because family members may find it difficult to accommodate legal processes that are not fully aligned with their family beliefs. Other findings of the study suggest that family heads find it difficult to adapt to ways that will benefit their families as long as the adaptations are perceived to be in conflict with their cultural values. The study also found that being part of family preservation services made family heads afraid of being judged by other community members. Lanesskog, Munoz and Castillo (2020) found that families at risk often fear being judged for being families whose children have been removed.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Considerable attention has been devoted to the premises that inform the provision of family preservation services, namely the crisis intervention perspective and the strengths perspective. The services provided are significant in preserving families and keeping the family as a functioning unit. The application of the strengths perspective through services provided to families seems to be effective. However, it is noted that the poor quality of the time that family members spend with each other and their minimal involvement with one another may compromise family structures. The findings of the study revealed that family preservation services prepare families to resolve their problems and assist them to create family rules that promote effective ways of dealing with family conflicts. Therefore, the study shares similar views with Coulshed and Orme (2012), who found that family preservation services should help families to make connections, to improve the level of care for one another, and to be able to confront and resolve problems as a family. The literature consulted for the study shows that family preservation services are supposed to assist families to feel relieved from family burdens, and assist families to gain full control of their lives to avoid the removal of children from their care. In an attempt to ensure that families gain full control of their lives, social workers must consider assisting families to improve their communication and parenting skills, and to increase the self-esteem of individual members.

It can be concluded that failure to assess the difficulties experienced by families within the provision of family preservation services will expose them to the risk of removal of their children and will discourage them from participating in services valuable for their livelihood. Therefore, it is recommended that social workers must pay particular attention to any obstacles that may lead to a lack of family participation in the services provided. Social workers need to pay attention to families' basic needs such as those related to their cultural beliefs, stigma and travel distances. If not addressed, these needs have the potential to undermine the benefits families may derive from family preservation services. The provision of family preservation services requires social workers and families to work together to ensure that family strengthening programmes have a positive impact on families.

Below are additional recommendations based on the study.

• A collaborative approach in the provision of family preservation services is recommended. Such an approach requires all parties involved within service provision and beneficiaries of the services to work jointly on tasks to assist families to resolve problems of concern to them. In addition, addressing ways of discouraging judgmental attitudes through awareness programmes may assist in reducing stigma in communities.

• The study also recommends that families, communities, social workers and public and private organisations must play an integral role in ensuring that families are preserved and supported during difficult times.

• It is further recommended that service satellite offices or mobile offices be introduced in areas with a high need for social services in South Africa to promote easy access to such services. For example, South African villages are often located kilometres away from offices that can provide professional assistance. Therefore, mobilising resources to develop satellite offices will bring services and professionals closer to marginalised societies.

• Lastly, it is recommended that research focusing on social workers' views on the effects of family preservation services be undertaken to provide a perspective from the practitioners' points of view.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences.

REFERENCES

Beesley, P., Watts, M. & Harrison, M. 2018. Developing your communication skills in social work. 1st ed. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Berger, L. & Font, S. A. 2015. The role of the family and family-centered programs and policies. Future of Children, 25(1): 155-176. [ Links ]

Berry, M., Cash, S. J. & Brook, J. P. 2000. Intensive family preservation services: An examination of critical service components. Child and Family Social Work, 5(3): 191-203. [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:77-101. [ Links ]

Collins, D., Jordan, C. & Coleman, H. 2010. An introduction to family social work. 3rd ed. Belmont: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Combrink, J. M. 2015. Family preservation services: Experiences offamilies at risk. Master's thesis. University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Coulshed, V. & Orme, J. 2012. Social work practice. 5th ed. Hampshire, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Dawson, K. & Berry, M. 2002. Engaging families in child welfare services: An evidence-based approach to best practice. Child Welfare, 81(2): 293-317. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development (DSD). 2001. Draft National Policy Framework for Families. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development (DSD). 2008. Manual on Family Preservation Services. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development (DSD). 2011. Annual report. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Department of Social Development (DSD). 2012. Norms and standards for services to families. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Dhludhlu, S. & Lombard, A. 2017. Challenges of statutory social workers in linking foster care services with socio-economic development programmes. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(2): 165-185. [ Links ]

Forrester, D., Kershaw, S., Moss, H. & Hughes, L. 2008. Communication skills in child protection: How do social workers talk to parents? Child & Family Social Work, 13(1): 41-51. [ Links ]

Fraser, M. W., Nelson, K. E. & Rivard, J. 1997. Effectiveness of family preservation services. Social Work Research, 21(3): 138-153. [ Links ]

Galvin, K. M., Braithwaite, D. O. & Bylund, C. 2015. Family communication: Cohesion and change. 9th ed. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Heneghan, A. M., Horwitz, S. M. & Leventhal, J. M. 1996. Evaluating intensive family preservation programs: A methodological review. Pediatrics, 97(4): 535-542. [ Links ]

Higham, P. 2006. Social work: Introducing professional practice. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Hooper-Briar, K., Broussard, A., Ronnau, J. & Sallee, A. 1995. Family preservation and support: Past, present, and future. Journal of Family Strengths, 1(1): 12-22. [ Links ]

Hurley, K. D., Griffith, A., Ingram, S., Bolivar, C., Mason, W. A. & Trout, A. 2012. An approach to examining the proximal and intermediate outcomes of an intensive family preservation program. Journal for Child and Family Studies, 21(6): 1003-1017. [ Links ]

Jhang, F. H. 2017. Negative life events and life satisfaction: Exploring the role of family cohesion and self-efficacy among economically disadvantaged adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22: 2177-2195. [ Links ]

Kapur, R. 2018. Barriers to effective communication. Postgraduate thesis. Delhi University, India. [ Links ]

Katz, I. & Hetherington, R. 2006. Co-operating and communicating: A European perspective on integrating services for children. Child Abuse Review, 15:429-439. [ Links ]

Lanesskog, D., Munoz, J. & Castillo, K. 2020. Language is not enough: Institutional supports for Spanish speaking client-worker engagement in child welfare. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(4): 435-457. [ Links ]

Lanz, M. & Tagliabue, S. 2014. Family intimacy measures. In: Michalos, A. C. (ed). Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer. [ Links ]

Lee, C. D. & Ayon, C. 2004. Is the client-worker relationship associated with better outcomes in mandated child abuse cases? Research on Social Work Practice, 14(5): 351-7. [ Links ]

Makoae, M., Roberts, H. & Ward, C. L. 2012. Child maltreatment prevention, readiness assessment: South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC. [ Links ]

Malatji, H. & Dube, N. 2017. Experiences and challenges related to residential care and the expression of cultural identity of adolescent boys at a Child and Youth Care Centre (CYCC) in Johannesburg. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(1): 109-126. [ Links ]

McAuley, C., McKeown, C. & Merriman, B. 2012. Spending time with family and friends: Children's views on relationships and shared activities. Child Indicators Research, 5: 449-467. [ Links ]

McGoldrick, M., Carter, E. A. & Garcia-Preto, N. 2011. The expandedfamily life cycle: Individual family and social perspectives. 4th ed. London: Pearson. [ Links ]

Miller, I. W., Ryan, C. E., Keitner, G. I., Bishop, D. S. & Epstein, N. B. 2000. The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2): 168-189. [ Links ]

Morris, H., Blewitt, C., Savaglio, M., Halfpenny, N., Carolan, C., Miller, R. & Skouteris, H. 2022. Using a realist lens to understand the Victorian Family Preservation and Reunification Response in the first year of implementation: Towards a better understanding of practice. Children and Youth Services Review,143: 106663. [ Links ]

Mosoma, Z. 2014. The formulation of the manual on family preservation services in South Africa and the experiences of social workers regarding the formulation and implementation. University of Pretoria, South Africa: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

Mosoma, Z. & Spies, G. 2016. Social workers' experiences with the South African policy manual on family preservation services. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 28(2): 187-202. [ Links ]

Nhedzi, F. 2014. The experiences and perceptions of social workers on the provision of family preservation services in the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan, Gauteng Province. Master's thesis. University of South Africa, South Africa. [ Links ]

Nhedzi, F. & Makofane, M. 2015. The experiences of social workers in the provision of family preservation services. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 51(1): 354-378. [ Links ]

Ntjana, N. J. 2014. The progress of developmental social welfare: A case study in the Vhembe district, Limpopo. Master's thesis. University of Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Nzuza, M. P. 2019. The implementation of family preservation services to children in need of care and protection within the Amajuba District Municipality, KwaZulu Natal. Master's thesis. University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. [ Links ]

Olson, D., Portner, J. & Bell, R. 1982. FACES II: Family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scale. St. Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota [ Links ]

Olson, D., Sprenkle, D. & Russell, C. 1983. Circumplex model of marital and family system: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Fam Process, 18(3): 4-28. [ Links ]

O'Neill, A. 2023. Fertility rate in South Africa. Economy & Politics. [Online] Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/578912/fertility-rate-in-south-africa/ [Accessed: 20/02/2023]. [ Links ]

O'Reilly, R., Wilkes, L., Luck, L. & Jackson, D. 2009. The efficacy of family support and family preservation services on reducing child abuse and neglect: What the literature reveals. Journal of Child Health Care: For Professionals Working with Children in the Hospital and Community, 14: 82-94. [ Links ]

Proctor, L. J. & Dubowitz, H. 2014. Child neglect: Challenges and controversies. In: Korbin, J. E. & Krugman, R. D. (eds.). Handbook of child maltreatment. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Proudlock, P. M. S. & Jamieson, L. 2014. Children's right to be protected from violence: A review of South Africa's laws and policies. Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1954. Department of Bantu Administration and Development. Natives Resettlement Act No. 19 of 1954. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Government Gazette, Vol. 378, No. 17678 (8 May 1996) Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 1997. Ministry of Welfare and Population. White Paper for Social Welfare. Notice 1008 of 1997. Government Gazette, Vol. 368, No. 18166. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2006. Children's Act, 38 of 2005. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944. (19 June 2006). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA). 2013. Department of Social Development. White Paper on Families in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Rodriguez-Jenkins, J. & Marcenko, M. O. 2014. Parenting stress among child welfare involved families: Differences by child placement. Children andyouth services review, 46: 19-27. [ Links ]

Saleebey, D. 2013. The strengths perspective in social work practice. 6th ed. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Sandoval, C. 2010. Children's social workers' experiences and perceptions on the family preservation program. Master's thesis. California State University, United States of America. [ Links ]

Sesane, M. P. & Geyer, L. S. 2017. The perceptions of community members regarding the role of social workers in enhancing social capital in metropolitan areas to manage HIV and AIDS. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(1): 1-25. [ Links ]

Sheafor, B. W., Horejsi, C. R. & Horejsi, G. A. 2000. Techniques and guidelines for social work practice. 5th ed. USA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Strydom, M. 2010. The implementation of family preservation services: Perspectives of social workers at NGOs. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 46(2): 192-208. [ Links ]

Strydom, M. 2012. Family preservation services: Types of services rendered by social workers to at-risk families. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(4): 435-455. [ Links ]

Strydom, M., Schiller, U. & Orme, J. 2020. The current landscape of child protection services in South Africa: A systematic review. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 56(4): 383-402. [ Links ]

Strydom, M., Spolander, G., Engelbrecht, L. & Martin, L. 2017. South African child and family welfare services: Changing times or business as usual? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(2): 145-164. [ Links ]

Swart, H. 2017. The contribution of volunteers to early intervention services in a community- based child protection programme at a selected non-governmental organisation. Master's thesis. Stellenbosch University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Thoburn, J., Robinson, J. & Anderson, B. 2012. Returning children home from public care. Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE): Research Briefing 42. [Online] Available: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/briefings/briefing42/ [Accessed: 10/10/2021]. [ Links ]

Tully, V. 2016. An evaluation of the safety parent programme in the Western Cape. [Online] Available: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/social-development/an_evaluation_of_the_safety_parent_programme_march_2017_final.pdf [Accessed: 15/10/2021]. [ Links ]

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Save The Children & World Vision. 2012. A better way to protect all children: The theory and practice of child protection systems. In Conference report. New York, NY: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, J. & Strydom, M. 2016. Utilizing group work in the implementation of family preservation services: Views of child protection social workers. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(4): 546-570. [ Links ]

Van Wert, M., Anreiter, I., Fallon, B. A. & Sokolowski, M. B. 2019. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: A transdisciplinary analysis. Gender and the Genome, 3(1): 1-21. [ Links ]

Wells, K. & Whittington, D. 1993. Child and family functioning after intensive family preservation services. Social Service Review, 67(1): 55-83. [ Links ]

Wilson, E., Goodwin, B., Hendley, H., Reed, D., Whitis, C., Rose, T. & Kestiaan, H. 2020. Right family, right time, right services: Evaluation of Indiana DCS family preservation services program. ACF-Children's Bureau. Indianapolis, Indiana. [ Links ]

Zeng, Y., Ye, B., Zhang, Y. & Yang, Q. 2021. Family cohesion and stress consequences among Chinese college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Public Health, 9:703899. [ Links ]

Article received: 5/5/2022

Article accepted: 14/6/2023