Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.58 no.2 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/58-2-1043

ARTICLES

The perceptions of students in an Open Distance Learning (ODL) institution on life skills as an HIV and AIDS prevention strategy

Prof. Boitumelo Joyce MohapiI; Dr Caroline AgboolaII; Dr Mmaphuti Percy DipelaIII

IDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. joycempohapi@yahoo.com

IIDepartment of Sociology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. agboolacaroline@gmail.com

IIIDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.dipelmp1@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Most people, including university students, are faced with the challenge of preventing infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). There is a need to ensure that students, future graduates and the future workforce enter the workforce as health-conscious citizens. This descriptive, explorative, qualitative study was conducted among students of the University of South Africa (Unisa), and it explored the students' perceptions of developing life skills as an HIV and AIDS prevention strategy. Focus group discussions were used as a means of data collection. The data collected were subjected to content analysis. The perception of the students showed that life skills may play a crucial role in the prevention of HIV and AIDS. The study revealed that learning about life skills is absent from the students' curriculum, and students want it to be included in their education. Some recommendations were made: the inclusion of HIV and AIDS education in the students' curricula and qualification; student support services should provide services that go beyond the provision of medication and condoms to include counselling services for students on mental health, behaviour and general health; compulsory life skills workshops and educational sessions should be made available to students at the beginning of registration cycles; and topics for the life skills workshops should encompass aspects that are related to HIV and AIDS as well as those that are not HIV- and AIDS-related.

Keywords: HIV and AIDS prevention, life skills, students, students support services, strengths perspective, Open Distance Learning

INTRODUCTION

HIV and AIDS are still a concern in many countries and continue to cause distress. Despite progress towards the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 95-95-95 targets, South Africa is still suffering from one of the largest HIV epidemics globally (Kim, Tanser, Tomita, Vandormael & Cuadros, 2021). According to the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2020), HIV infections have increased by 72% in Central Asia and Latin America, by 22% in the Middle East and North Africa and by 21% in Latin America. UNAIDS (2020) further reports that globally there were 690,000 AIDS-related deaths in 2019 and 1.7 million new infections.

Mozambique, South Africa and Tanzania accounted for more than half of new HIV infections and deaths from AIDS-related illnesses in the Southern African region in 2017. South Africa, as indicated above, is still facing huge challenges in managing the spread of HIV and AIDS. The total number of persons living with HIV (PLHIV) in South Africa increased from an estimated 3,8 million in 2002 to 8,2 million by 2021. This high rate of HIV prevalence in South Africa is confirmed by UNAIDS (2020), which states that the country has the biggest HIV epidemic in the world. South Africa, furthermore, accounts for a third of all new HIV infections in southern Africa. In 2018 there were 200,000 new HIV infections and 72,000 South Africans died from AIDS-related illnesses.

According to Murwira, Khoza, Jabu, Maputle, Mpeta and Nunu (2021), studies on youth sexual behaviours in South Africa show that young people continue to face the greatest risk of HIV infection. The authors state that other surveys reported that South African youths (15-24 years) in general exhibit unsafe sexual behavioural practices. These risky behaviours include, amongst others, a high average number of partners, sex with unknown persons, inconsistent use of condoms, negative views about condom use, and abuse of various substances.

HIV and AIDS affect South Africa economically, because the most affected people are between 15 and 49 years old and hence the most economically active, according to the Association of African Universities (2010). It is further states that, "if the importance of scientific, technical and social knowledge of HIV and AIDS is to be helpful to students, it must lead to value re-orientation, attitude change and behaviour modification" (Association of African Universities, 2010). This can only happen if HIV and AIDS awareness penetrates all aspects of institutional culture. That is the main reason that formal curriculum activities (i.e. that which is consciously taught) must be complemented with an informal curriculum which is taught through intensive, interactive exposure. Life skills workshops and awareness sessions can serve to fulfil this role.

HIV and AIDS present a challenge that affects not only the government, but also most citizens, who are either infected with the virus or indirectly affected. According to UNAIDS, globally, there were 690,000 AIDS-related deaths in 2019 and 1.7 million new infections (UNAIDS, 2020). Given the growing number of new infections, higher education institutions (HEIs) are being challenged to join the fight against HIV and AIDS. HEIs need to advance their strategies to prevent, eliminate or minimise the spread of HIV and AIDS. As such, results from this study will be useful in the HEIs' fight against HIV and AIDS. The following research question guided this study: The research question which guided this study is: what are the perceptions of students at Unisa regarding life skills as a behaviour change strategy in the prevention of HIV and AIDS?

BACKGROUND

The Higher Education HIV and AIDS Programme (HEAIDS) was established because the higher education sector has a critical role to play in the fight against the spread of HIV and AIDS (Woods & Pillay, 2016). Policy is needed for prevention of HIV and AIDS as well as relevant interventions in higher education institutions (HEAIDS, 2008), but there is also a need to integrate prevention strategies into the curriculum so that students are equipped with the necessary skills to improve the society in which they live while they are students and after they graduate. However, it has been noted that little has been done to integrate HIV and AIDS awareness into the curriculum in higher education institutions (Woods & Pillay, 2016).

Similarly, the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) established the Higher Education and Training HIV and AIDS Programme (HEAIDS) in 2000 to develop and support HIV-mitigation programmes at South Africa's public-sector universities and technical and vocational education and training colleges (TVETs) In this regard, the European Union states that:

HEAIDS was launched in 2000 by South Africa's Department of Education in collaboration with universities. The first phase was funded by the British and Irish official development programmes, as well as the American Centre for Disease Control. Some of the key focus areas included curriculum integration as well as peer education (European Union, 2017).

The DHET Strategic Plan: 2010-2015 proposed the establishment of a transformation unit in the DHET that will deal with issues such as student development and support, gender equity, HIV and AIDS, and career information and guidance, among others (DHET, 2012).

Some HEIs have resorted to life skills education as one of their intervention strategies to empower students as their internal stakeholders. The World Health Organisation (1997) defines life skills as the ability to embrace adaptive and positive behaviour that enables individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life, and states that this an important aspect in HIV prevention and preparation of young people for their changing social circumstances (Liu, Liu, Yan, Lee & Mayes, 2016). Life skills training is defined as:

learning experiences that aim to develop knowledge, attitudes and especially (psychosocial competencies) that will enable learners to take positive actions towards developing and maintaining healthy behaviours, environments, and quality of life (Liu et al., 2016:27).

In the context of the HIV and AIDS pandemic, the aim of life skills training is to develop young people's knowledge and help them to cultivate the skills needed for healthy relationships, effective communication and responsible decision-making that will protect them and others from HIV infection and optimise their health (World Health Organisation, 1997). Additionally, life skills training covers important issues related to empowering young people to adopt new values. In the context of this paper, life skills will be defined as skills that a person must develop in a vigorous and positive manner to function efficiently in society. A vital part of life skills involves empowering and allowing students to adopt values that will positively influence them to take informed decisions as far as HIV in concerned.

There is a need for rigorous measures, such as life skills training and a massive HIV-prevention campaign, beginning with the promotion of condom use and the reduction of multiple concurrent partnerships. Hence, it was proposed that the programmes should deal with sexual coercion, transactional sex, intergenerational sex, risky sex linked to the use of alcohol and drugs, the lack of job opportunities for young women, and ignorance, powerlessness and poverty (Ramaphosa, 2015). Such campaigns, if implemented and sustained, may benefit students so that new infections can be curtailed and existing infections properly managed so as to reduce reinfections. Structural approaches including cash transfers, vouchers and food and nutritional support show potentially promising results as a possible strategy to reduce vulnerability to HIV infection in girls and young women (UNAIDS, 2013). While these new approaches have proven effective in trials, they have not yet led to a measurable and sustained decline in new infections at population level to a great extent because of the failure to implement these strategies to scale (UNAIDS, 2013). Furthermore, some young girls and women misuse these initiatives by enjoying the benefits of receiving a government grant, but failing to take responsibility for their wellbeing by adopting positive behaviour geared towards the prevention of HIV and AIDS.

There are programmes designed by HEAIDS projects that are aimed at consolidating the educational sector's response to HIV and AIDS based on gaps and weaknesses identified in the spread of HIV and AIDS at institutions of higher learning. One such project is the zero-prevalence study, which sought to establish prevalence rates for students and staff at HEIs in South Africa (HEAIDS, 2008). The majority of young people in South Africa are aware of HIV and AIDS and also about some aspects related to this pandemic. Young people's awareness is mainly centred on three issues: namely that HIV and/or AIDS can but does not necessarily result in death; it is an infectious disease; and several sources of information could be accessed in the community (Taukeni & Ferreira, 2016).

RESEARCH QUESTION

The research question which guided this study is: "what are the perceptions of students at Unisa regarding life skills as a behaviour change strategy in the prevention of HIV and AIDS?"

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this research were:

• To explore the perceptions of students about developing life skills as a strategy to prevent HIV and AIDS; and

• To describe the students' perceptions about life skills as a behaviour change strategy in the prevention of HIV and AIDS.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The theory underpinning this study draws on the strengths perspective. According to this perspective, all human beings have a natural power within themselves that can be harnessed (Miley, O'Melia & Du Bois, 2007). When applied to this study, it means that university students are perceived to have certain strengths, which can be enhanced through life skills training. This will in turn enable them to avoid risky behaviours which are conducive to the spread of HIV and AIDS. The following are the goals of the strengths perspective: empowerment, membership, resilience, healing and wholeness, dialogue and collaboration, and suspension of disbelief (Saleebey, 1997). The strengths perspective focuses on peoples' strengths, and not their deficiencies. Life skills are skills that are taught to build on the strengths that people already have, therefore life skills training resonates with the strengths perspective.

The strengths perspective is based on several principles (Saleebey, 1997). The first is that every individual, group, family and community has strengths. In this context, it means that all university students have strengths that should be acknowledged. Another principle states that trauma and abuse, illness and struggle may be injurious, but they may also be sources of challenge and opportunity. When applied to university students, this means that even if they are facing problems, these can also be seen as opportunities with which to begin a new chapter in their lives. As far as aspirations are concerned, the strengths perspective urges those who offer a service to students to assume that the students do not know the upper limits of the capacity to grow and change of the individual student or group of students, so they have to take their students' aspirations seriously. Collaboration and the environment are also emphasised in the strengths perspective, since this affirms that we can best serve people by collaborating with them, provided that the environment in which they are is full of resources. When applied to university students and life skills, this means that we have to create an environment conducive to their acquiring life skills.

RESEARCH METHODS

Research approach and design

This study utilised a qualitative approach with a descriptive and exploratory design, as the research is primarily concerned with the meaning that subjects give to their life experiences (Fouché & Schurink, 2011). Of interest to this study are the perceptions of students from learning centres at Unisa in relation to developing life skills as a strategy in the prevention of HIV and AIDS. These centres are situated across five provinces within South Africa: Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, Northern Cape and Western Cape. In order to explore the perceptions of students in relation to HIV and AIDS prevention through life skills, it was important for participants to be allowed an opportunity to share "points of view, experiences, wishes and concerns" (Monette, Sullivan & De Jong, 2005). The qualitative approach used allowed "a thick description of the stories from the participants" (Giles, 2009) and "the subjective assessment of attitudes, opinions and behaviour" to be gathered (Kothari, 2006).

Sampling

Purposive sampling (Lambert & Lambert, 2012) was used in that the Unisa learning centres used were predetermined. The inclusion criterion was that a student should be registered to study at the colleges of the University of South Africa. With regards to the participants, all students within the selected centres who were available and willing to attend the focus group session were included in this study, thereby making it convenience sampling. Hence, a combination of purposive and convenience sampling were used for this study. One can simply decide the purpose that one wants the informants to serve and take what one can get when using purposive sampling (Bernard & Ryan, 2010). Based on the ease of access (Kothari, 2006), the researchers selected a sample of 39 students to participate in this study.

Data collection and data analysis

Data were collected through focus group interviews. A focus group is "a carefully planned discussion with a small group of people on a focused topic" (Guest, Namey & Mitchell, 2013). Five focus group interviews were conducted in urban areas where Unisa learning centres are situated. However, some of these centres serve students who commute from rural areas on a daily basis. Content analysis (Colorafi & Evans, 2016) was conducted to analyse the collected data. In using content analysis, the participants' responses were transcribed, coded and categorised into themes. Words, sentences and phrases formed the basis of data analysis.

To ensure rigour and trustworthiness, the researcher used the criteria put forward by Guba (Schurink, Fouché & De Vos, 2011) when conducting the study. These criteria are credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. To ensure credibility, all participants selected were Unisa students. More than one region was involved in order to ensure that the results are transferable, to a limited extent, to other similar Unisa regions. The focus group discussions were recorded, which guarantees dependability. The recordings of the focus group discussion render them confirmable.

Ethical considerations

Ethics is a set of moral beliefs which are suggested by an individual or group, is widely accepted and offers rules and behavioural expectations about the most correct behaviour towards experimental subjects and respondents, employers, other researchers, sponsors and students (Strydom, 2011:84).

Ethical clearance to conduct the study was granted by Unisa. In addition to this, the ethical principles of informed consent (Ferreira & Serpa, 2018), mitigation of potential harm to participants (Brown, Spiro & Quinton, 2020) and anonymity (Lancaster, 2017) were adhered to in conducting the study. Informed consent implies that all participants in the focus group discussions were informed about the purpose of the research and how the focus groups will be conducted. The written consent of all the participants was also sought and obtained. Mitigation of potential harm to participants means that, in conducting research, participants may be harmed either physically or emotionally; in conducting this study, all reasonable attempts were made to protect the respondents from possible harm. As far as anonymity is concerned, the dissemination of research results was discussed with the respondents and they were informed that the research results will be reported in such a manner that no information can be linked to a specific individual.

RESULTS

The results were classified according to the following themes: participants' characteristics, the comprehension of the concept "life skills", perception of their roles and the benefits of life skills training in the prevention of HIV and AIDS, timing, frequency and location of life skills training workshops, and topics to be covered in life skills training. From time to time, transcripts from the focus groups were used to support themes that emerged. In this study, 'FG' stands for 'focus group', followed by a number to represent a specific focus group, while 'P' is used to identify a specific participant in a focus group. For example, FG4P1 indicates participant 1 from focus group 4.

Participants' characteristics

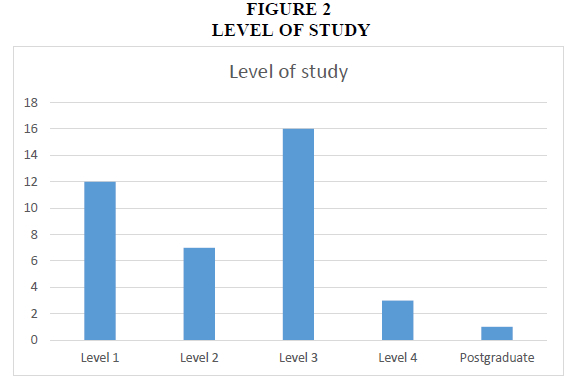

The participants consisted of 14 males and 25 females. The participants' ages ranged from 18 to above 45 years. The participants were undergraduates and postgraduate students. The participants' biographical data are presented in the following figures and tables.

Figure 1 shows that the ages of the participants in the study ranged from 18 to above 45 years. However, only one participant was older than 45. The majority of participants were between the ages of 26 and 35 years.

Figure 2 indicates that the majority of participants (16) were undergraduates who were in year three of their studies, and 12 participants were in year one. Only one participant was registered for postgraduate studies.

Figure 3 shows the participants who took part in this study were from five colleges, namely, the College of Human Sciences, College of Law, College of Education, College of Economic and Management Sciences, and the College of Science, Engineering and Technology. The College of Human Sciences had the highest number of participants.

South Africa is divided into nine provinces, but Unisa is divided into seven regions: Western Cape, Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Midlands (see Figure 4). The Midlands is a combination of the provinces of the Northern Cape, Free State and North-West. The study was conducted in the Midlands, Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape regions of Unisa. The four regions were selected based on availability of participants and resources.

Comprehension of the concept "life skills"

Most of the participants had a clear understanding of what life skills entailed. The common theme that emerged was that life skills involve formal or informal training that prepares people to deal with life's challenges. They further mentioned that when internalised, life skills empower participants and bring about growth in some areas of their lives. In line with their understanding, the participants then went on to share their perceptions of the role of life skills in raising awareness about HIV and AIDS.

The roles and benefits of life skills training in the fight against HIV and AIDS

The participants agreed that life skills would assist in raising awareness and lead to behaviour change among university students, who tend to be easily tempted to engage in risky behaviour. According to FG4P1, students entering tertiary institutions are ignorant because they have the misguided belief that they "know too much" and "that it [HIV infection] will not happen to us"". Research has revealed that stigma, discrimination, blame and collective denial were potentially the most difficult aspects of the HIV and AIDS epidemic to deal with (Pulerwitz, Michaelis, Weiss, Brown & Mahendra, 2010). The participants further expressed the need for behaviour change in a context in which there is a risk of HIV Infection. Such risks might arise as a result of students' "starting to drink, recklessly using drugs and becoming irresponsible". In the context of this study, the participants unanimously agreed that life skills can assist in preventing HIV and AIDS.

The benefits of life skills training were discussed by the participants. This is attested to in FG2P1's submission that life skills training will ensure that "students do not graduate with distinctions from the university into the grave". Furthermore, the participants thought that life skills training will equip students to remain positive, irrespective of the presence of a myriad of social ills. FG2P6 contextualised the benefits of life skills training in the absence or deterioration of nuclear family structures, and claimed that life skills training will make students conscious of "their exposure to a variety of vulnerabilities''".

Similarly, another participant described life skills training as like a "surrogatefamily". FG2P3 mentioned that "life skills training will give students a sense of common understanding of social ills and a common goal in empowering communities, thereby reducing the spread of HIV and AIDS". The participants' views are in line with the contention that what humans do, think and desire is partly influenced by key elements of social life, including norms, values, networks, structures and institutions (Auerbach, Parkhurst & Cáceres, 2011). FG5P2 used the following analogy to express the role of life skills training: "It is like being given a glass and being shown where the tap of water is". Such expressions link the benefits of life skills training with survival.

The frequency, timing and location of life skills training workshops

Unisa has two registration cycles for the academic year, one in semester 1 and the other in semester 2. The participants thought that life skills training workshops should be held at least once in a semester so as to target the new students. They also felt that HIV and AIDS testing and counselling should accompany the life skills training workshops in order to identify and assist vulnerable students sooner rather than later. The participants expressed the view that such programmes should be offered outside of examination periods. Although some participants suggested that life skills training programmes be held "after examinations'", this idea was not supported by the majority of participants, who opted for "before examinations". FG2P4 justified their preference for "before examination sessions" as follows: "Once students are done with examinations, they might not want anything much to do with Unisa as it would be their break period". The participants noted that life skills training in relation to HIV and AIDS prevention should be offered earlier and not only at tertiary level. FG1P2 lamented that "By the time students receive life skills training, it might be too late". In support of the need for early life skills training, some participants shared their experiences of children becoming pregnant as early as age 12. To demonstrate their insight into the long-term negative impact of HIV and AIDS, if students failed to take life skills training seriously, FG1P4 mentioned that "an educated workforce will not sustain the economy of the country as they will be too sick to work".

In addition, on the frequency and location of life skills training, the participants mentioned that it should be offered on the campus and in city centres. According to the participants, life skills training should be offered at least monthly or every semester. The participants noted that life skills training should be packaged in the form of "edutainment", and in collaboration with various celebrities. In this way, the participants posited that many people, especially young people, would attend. Given the ODL nature of Unisa, holding life skills training monthly was considered by some participants as occurring "too regularly". This category of participants noted that sessions once per semester only is sufficient. In order for life skills training to be effective, the participants expressed the view that "the university should offer life skills training in collaboration with other students, that is, their peers". The participants submitted that life skills training be offered quarterly, and their peers be empowered to run these life skills training sessions. In other words, the peers are to functions as peer educators. The use of peer educators would prevent individual students from feeling that they were being targeted (FG1P3). Some participants maintained that certain content on television can undermine the effects of life skills training at higher education institutions. Also, the participants explained that they do not desire the types of workshops that would take the format of an "event", but they preferred those that are offered as a series of workshops or discussions.

The participants, specifically those from rural areas, expressed concerns that young people, that is, their peers, tend to deny the existence and severity of HIV and AIDS. By comparing open and distance learning (ODL) institutions and residential universities, the participants noted that ODL students' lives are not centred on the university campus. The participants held the view that life skills training programmes in residential universities tend to have an impact on the behaviour change of students because they are offered on a consistent basis. Hence, the participants recommended that ODL students be equipped with life skills that are relevant to their communities and they warned against "once-offprogrammes " that do not deal with " real issues". In contrast, some participants were concerned that there is HIV and AIDS information overload in some communities. Therefore, they believe that "HIV and AIDS only workshops" would not be beneficial. The participants agreed that life skills training can assist as "in townships, there is a sign of danger" (FG4P4). This statement points to the high level of exposure to HIV and AIDS that people in rural communities experience. The participants agreed that many people and organisations have been spreading information about HIV and AIDS. However, their concern was that there are many illiterate people who still do not know much about HIV and AIDS, especially in rural areas.

Topics to be covered in life skills training

The participants suggested various topics that should be included in life skills training. Some suggested topics are related to HIV and AIDS, whereas others were completely unrelated. The topics are outlined below.

Topics related to HIV and AIDS

The participants explained that life skills training should include the following topics that are related to HIV and AIDS: basic information about HIV and AIDS - such as, it is acquired, prevention, treatment and living with HIV and AIDS; the lifestyle of a person living with HIV and AIDS; nutrition; physical exercise; contraception; safer sex; support and counselling services; referrals; the effects of HIV on the younger generation, communities and students; relationships, including serodiscordant partners - where one partner is HIV+ and the other is HIV-; CD4 counts; phases and stages of HIV and AIDS; implications for conceiving when HIV+; in vitro fertilisation; cultural issues around HIV and AIDS; myths about HIV and AIDS; different types of condoms; contraceptives that empower females; and how to live with infected individuals, including dealing with stigma. With regards to how HIV and AIDS-related topics should be dealt with, participants suggested that facilitators should involve real people who are HIV positive so that they can relate their first-hand experiences and offer practical advice.

Other topics unrelated to HIV and AIDS

In carrying out life skills training, the participants suggested the inclusion of other topics that are unrelated to HIV and AIDS. These topics are broadly categorised into two: the first encompasses health-related topics that can be dealt with by health professionals, and the second entails topics that fall within the ambit of educationists and social service professionals, such as social workers, counsellors and psychologists. Some of the health-related topics that were mentioned in the first category are first aid, cancer, high blood pressure, tuberculosis, heart attack and diabetes. Regarding the second category, the participants suggested the following topics: social behaviour (taking responsibility for your decisions and actions), career guidance, academic literacy, developing a culture of reading and writing, moral regeneration, dealing with peer pressure (including saying "No" to sexual activities), gender equality, sexual orientation, diet, relationships, self-concept, self-confidence, objectification of women, decisionmaking, parental guidance. lifestyle of sex workers, and self-esteem workshops for females.

DISCUSSION

The study was carried out to provide an explorative and descriptive analysis of Unisa students' perceptions of the prevention of HIV and AIDS through life skills training. As presented in the results, five main themes emerged. The gender ratio of participants in this study (about 1 male to 2 females) is similar to the student profile of Unisa. In 2018, female students accounted for about 66.2% (based on researcher's own calculations) of the total student population (UNISA, 2018). In this study, the participants understood what constitutes life skills. The participants' understanding of life skills is consistent with the definition by the Peace Corps, which states that:

Life skills is viewed as a complete behavioural change that concentrates on the development of the skills needed for life such as communication, decision-making, thinking, managing emotions, assertiveness, self-esteem building, resisting peer pressure, and relationship skills (Peace Corps, 2001).

Life skills are necessary in the development of psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, behavioural and resilience skills in order to be able to navigate life's challenges and be a productive member of society (Nasheeda, Abdullah, Krauss & Ahmed, 2019). Similarly, this study found that life skills training plays a significant role and is beneficial in the prevention of HIV and AIDS. This was reflected in the participants' opinions that life skills training can bring about awareness of the disease and lead to behaviour change among students at the university studied, as well as equip them with knowledge on how to deal with social ills. The participants maintained that other social ills, such as rape and child molestation, can also be curbed through life skills training. It has been noted that these social issues affect many students who are studying at Unisa, and that most of the students had experienced domestic violence, physical and verbal abuse, sexual trauma and rape (Schenck, 2009). The participants were also of the opinion that life skills are critical to minimise the stigma associated with HIV and AIDS.

The frequency, timing and location of life skills training workshop is another theme that emerged in this study. The participants suggested that the workshop should be an ongoing process that should be conducted every semester so as to enlighten the new students on the issue of HIV and AIDS prevention. The participants had conflicting opinions on when the workshops should be done; some suggested after examinations, while others were of the opinion that this is not advisable, because students may not be interested as they may feel that they are on a break from the institution by that time. The participants indicated that the workshops should be presented at the various Unisa campuses and in city centres. Peer educators were noted by the participants as an important element in the workshops on life skills training in the prevention of HIV and AIDS. According to HEAIDS (2015), peer education as a concept is widely used to describe interventions where people who are similar in terms of age, background and/or social status educate and inform each other about a wide variety of issues. Peer educators are often used in the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections globally. Peer educators are people who have similar characteristics to those of the target audience, and they train the population on specific issues so as to increase their awareness and stimulate behavioural changes among the groups. It is believed that peer educators enjoy some level of trust from their peers and this creates an enabling environment for the discussion of sensitive topics which encourages individual behaviour change among the target group (Schenck, 2009). This assertion is supported by this study participants' request that peer educators engage them in life skills training on HIV and AIDS prevention, as it suggests that they have trust in the peer educators and are open to gaining knowledge from them. Studies (Medley, Kennedy, O'Reilly & Sweat, 2009; Menacho, Galea & Young, 2015) indicate that peer educators or leaders are effective in the improvement of health behaviours. The participants' suggested topics for the life skills training workshops centred on HIV and AIDS-related topics and those not related to HIV and AIDS. Topics suggested include HIV and AIDS transmission methods, prevention and treatment, living positively with the disease, and reproduction with a specific focus on HIV and AIDS, chronic diseases and terminal illnesses.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Life skills training is an important tool in the prevention of HIV and AIDS, particularly among students in higher education institutions or tertiary institutions. This is even more important given that the age group 15-24, which includes a lot of tertiary institution students, constitutes nearly half of all new HIV infections worldwide, and this demographic is more prone to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (Asante, Osafo & Doku, 2016). Life skills training equips students of tertiary institutions with knowledge not only on the prevention of HIV and AIDS, but also on the various aspects of HIV and AIDS, such as how to properly manage the disease - this is particularly important for those who are already infected or have family members or friends living with the disease. The results from this study further indicate the various aspects of dealing with HIV and AIDS that can benefit from life skills training. The effect of life skills training in the prevention of HIV and AIDS may have a domino effect and transcend the barriers of the tertiary institutions where they are taught by extending the knowledge acquired to the various families and communities the students come from. Similarly, students who are equipped with such knowledge will join the labour market at some point in their lives and become part of a well-informed workforce on the prevention of HIV and AIDS based on the life skills training that they went through as students in tertiary institutions, in this case a university.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study investigated students' perceptions of life skills as an HIV and AIDS prevention strategy. Thirty-nine students participated in five focus groups. The results showed that life skills training as an HIV and AIDS preventive measure is important in the spread and management of the disease, and this is knowledge that students want to acquire. The following recommendations are based on the results of the study.

First, there is a need for an integrated curriculum model in which all disciplines incorporate HIV and AIDS education in their curricula and qualifications. The rationale behind this recommendation is based on the proposal that HIV and AIDS should be made relevant to the life and career prospects of every graduate. Moreover, every university educator must be aware of the ways in which HIV and AIDS affects their specific discipline. Second, student development services should not be limited to the issuing of drugs, condoms and medicines. They should offer a holistic service, which should include the provision of counselling services that deals with mental health issues and assistance to improve students' general health and behaviour. Third, life skills workshops, with a focus on HIV and AIDS prevention, should be offered to students at the beginning of each registration cycle per semester. Topics for the life skills workshops could be differentiated according to the level of study. Since Unisa is an open distance learning institution, the workshops should be offered in a blended mode so that students who have access to technology can participate in the workshops online, while those students who do not have access to technology have the option of attending face-to-face sessions. In addition, apart from HIV and AIDS-specific topics, other health-related topics should be included in the life skills workshops. For example, topics on cancer, heart problems and diabetes. Other social issues that should be covered in the workshops include career guidance, taking responsibility for your decisions and actions, developing a culture of reading, dealing with peer pressure, gender equality, sexual orientation, and guidelines for a healthy diet and lifestyle.

REFERENCES

ASANTE, K. O., OSAFO, J. & DOKU, P. N. 2016. The role of condom self-efficacy on intended and actual condom use among university students in Ghana. Journal of Community Health, 41: 97-104. [ Links ]

ASSOCIATION OF AFRICAN UNIVERSITIES. 2010. The response of Higher Education Institutions in Africa to the HIV and AIDS epidemic. Accra: Association of African Universities. [ Links ]

AUERBACH, J. D., PARKHURST, J. O. & CÁCERES, C. F. 2011. Addressing social drivers of HIV and AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice, 6(3): 5293-5309. [ Links ]

BERNARD, H. R., & RYAN, G. W. 2010. Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. California: Sage. [ Links ]

BROWN, C., SPIRO, J. & QUINTON, S. 2020. The role of research ethics committee: friend or foe in educational research? An exploratory study. British Educational Research Journal, 46(4): 747-749. [ Links ]

COLORAFI, K. J., & EVANS, B. 2016. Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4): 16-25. [ Links ]

DHET (DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING). 2012. DHET Strategic Plan 2010 to 2014 (Revised March 2012). Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training. [ Links ]

EUROPEAN UNION. 2017. The Higher Education AIDS Programme in South Africa: a real force for transformation. [Online] Available https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/articles/higher-education-aids-programme-south-africa-real-force-transformation [Accessed 2021/05/10)]. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, C. M., & SERPA, S. 2018. Informed consent in social sciences research: ethical challenges. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 6(5): 13-23. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C. B., & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A. S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C. B., DELPORT, C. S. L. (eds.). Research at grassroots for the social sciences and human service professions. 4th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

GILES, D. 2009. Phenomenological researching the lecture-student-teacher relationship. Some challenges encountered. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 2(2): 108-111. [ Links ]

GUEST, G., NAMEY, E. E., & MITCHELL, M. L. 2013. Collecting qualitative data. California: SAGE. [ Links ]

HEAIDS. 2008. Policy and strategic framework on HIV and AIDS for higher education. Pretoria: HESA. [ Links ]

HEAIDS 2015. Crucial conversations for peers: a fresh approach. Pretoria: HEAIDS/Universities South Africa. [ Links ]

KIM, H., TANSER, F., TOMITA, A., VANDORMAEL, A. & CUADROS, D. 2021. Beyond HIV prevalence: identifying people living with HIV within underserved areas in South Africa. BMJ Global Health, 6: 1-10. [ Links ]

KOTHARI, C. R. 2006. Research methodology: methods & techniques. 2nd ed. New Delhi: New Age International. [ Links ]

LAMBERT, V. A. & LAMBERT, C. E. 2012. Qualitative descriptive research: an acceptable design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 16(4): 255-256. [ Links ]

LANCASTER, K. 2017. Confidentiality, anonymity and power relations in elite interviewing: conducting qualitative policy research in a politicised domain. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(1): 93-103. [ Links ]

LIU, J., LIU, S., YAN, J., LEE, E. & MAYES, L. 2016. The impact of life skills training on behaviour problems in left-behind children in rural China: a pilot study. School Psychology International, 37(1): 73-84. [ Links ]

MEDLEY, A., KENNEDY, C., O'REILLY, K. & SWEAT, M. 2009. Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [Online] Available https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3927325/pdf/nihms549757.pdf [Accessed 2020/09/14]. [ Links ]

MENACHO, L. A., GALEA, G. T. & YOUNG, S. D. 2015. Feasibility of recruiting peer educators to promote HIV testing using Facebook among men who have sex with men in Peru. AIDS Behaviour, 19: S123-S129. [ Links ]

MILEY, K. K., O'MELIA, M., & DU BOIS, B. 2007. Generalist social work practice: an empowering approach. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

MONETTE, D. R., SULLIVAN, T. J., & DE JONG, C. R. 2005. Applied social research. 6th ed. Australia: Thomson Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

MURWIRA, T. S., KHOZA, L. B., JABU, T. M., MAPUTLE, S. M., MPETA, M. & NUNU, W. N. 2021. Knowledge of students regarding HIV/AIDS at a rural university in South Africa. The Open AIDS Journal, 15: 42-51. [ Links ]

NASHEEDA, A., ABDULLAH, H. B., KRAUSS, S. E. & AHMED, N. B. 2019. A narrative systematic review of life skills education: effectiveness, research gaps and priorities. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(3): 362-379. [ Links ]

PEACE CORPS. 2001. Life skills manual. Information collection and exchange. Publication No. M0063. Washington: Peace Corps. [ Links ]

PULERWITZ, J., MICHAELIS, A., WEISS, E., BROWN, L. & MAHENDRA, V. S. 2010. Looking back, moving forward: reducing HIV-related stigma, horizons studies 2000 to 2007. Horizons Synthesis Background Papers. Washington, DC: Population Council. [ Links ]

RAMAPHOSA, C. 2015. Keynote address at the 7th SA AIDS Conference, 9 June 2015. South Africa: Durban. [ Links ]

SALEEBEY, D. 1997. Introduction: power in the people. In: SALEEBEY, D. (ed.). The strengths perspective in social work. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, R. 2009. The socio-economic realities of the social work students of the University of South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 45(3): 299-313. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C. B. & DE VOS, A. S. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A. S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C. B., DELPORT, C. S. L. (eds.). Research at grassroots for the social sciences and human service professions. 4th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. 2011. Ethical aspects of research in the social sciences and human service professions. In: DE VOS, A. S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C. B., DELPORT, C. S. L. (eds.). Research at grassroots for the social sciences and human service professions. 4th ed.. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

TAUKENI, S. & FERREIRA, R. 2016. HIV and/or AIDS awareness among adolescents in a South African at-risk rural community. South African Journal of HIV Medicine. [Online] Available https://sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/hivmed/article/view/418/827 [Accessed 2021/03/14]. [ Links ]

UNAIDS (UNITED NATIONS PROGRAMME ON HIV AIDS). 2013. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

UNAIDS (UNITED NATIONS PROGRAMME ON HIV AIDS). 2020. 2020 Global AIDS update: seizing the moment. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

UNISA (UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2018. UNISA integrated report. Pretoria. [ Links ]

WOODS, L. & PILLAY, M. A. 2016. A review of HIV and AIDS curricular responses in the higher education sector: where are we now and what next? South African Journal of Higher Education, (30)4: 126-143. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 1997. Life skills education in schools. Revised edition. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [ Links ]