Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.58 no.2 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/58-2-1039

ARTICLES

Witness protection programme: the views of witnesses and staff members on how children are affected by the admission of their parents into the programme

Dr Lucy Nthepa Mphaphuli

Office for Witness Protection, National Prosecuting Authority, Pretoria, South Africa. Lucy.mphaphuli@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Children, although innocent, are often admitted into the witness protection programme with their parents and, as a result, they experience isolation and social uprooting. This qualitative study aimed to describe the views of witnesses and staff members on how children are affected by the admission of their parents into the witness protection programme in South Africa. The ecological systems perspective, which recognises the impact of the environment on human functioning, and the person-in-environment perspective provided the theoretical framework. The findings confirmed the hardships of children in coping with the admission of their parents into the witness protection programme.

Keywords: children, family contact, social uprooting, social work intervention, witness protection programme, witness

INTRODUCTION

Crime has increased progressively across the globe in recent years, with criminal syndicates employing more sophisticated methods not only in their criminal activities, but also in the intimidation of witnesses (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008). Witnesses are increasingly compelled to go into the protection programme for their own safety and the safety of their families. Without protection, some witnesses are unable to deliver their testimonies in court, because they fear for their own and their families' lives. Protection programmes are thus necessary to ensure the protection of witnesses as well as to aid the criminal justice system to secure successful prosecutions (Fery, 2012). A higher conviction rate is reported in countries with witness protection programmes compared to those without (Kariri & Salifu, 2016).

Despite the benefits to the witnesses and their families, witness protection programmes impose far-reaching, though unintended, consequences on witnesses and a huge burden on their children. When parents are admitted into the programme, some go in with their children, while some children are left behind with relatives. Children who are in the programme struggle to cope without their grandparents, siblings and cousins, while those who are in the care of their relatives at home find it difficult to cope without parents. Kaur (2011) refers to the impact of being admitted into witness protection as the "rebirthing" of witnesses and families, especially children, because they terminate their association with family and friends, conceal their history, and assume a new identity far away from home in an unfamiliar area. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2008), children find it difficult to integrate into the demanding environment of the programme. Children also find it difficult to establish new friends and adjust to the new school environment, leading to feelings of isolation and loneliness. They live in isolation with constant feelings of fear of saying something that could reveal their true identity and compromise the safety of the entire family (Demir, 2018). Separation and isolation expose children to a life of stress and anxiety that could result in long-term mental health challenges, if not properly managed (Hendrick, 2009).

While there is literature on the important role of witness protection programmes globally, very little attention has been devoted to the South African context and no studies focus on how children experience and cope with the admission of their parents into the programme. A study by Kariri and Salifu (2016) in South Africa, for example, focused on the number of convictions and prison terms that resulted from these witnesses' testimonies. Mahony (2010) concentrated on the shortage and the importance of witness protection programmes in Africa. Demir (2018) investigated the success of the witness protection programmes and the study findings show a 0% death rate for witnesses while under active protection. Mujkanovic (2014) evaluated the impact of criminal activities on the well-being of witnesses and the role of support. Beune and Giebels (2013), on the other hand, focused on the extent of the social distress experienced by witnesses as a result of being admitted into the programme and the role of psychosocial support.

The lack of this knowledge leads to a scarcity of interventions that are responsive to the needs of the witnesses' children. This study seeks to gain an in-depth understanding of the views of witnesses and staff members on how children are affected by the admission of their parents into the witness protection programme in South Africa, with a view to helping social workers to develop appropriate interventions to mitigate such challenges. To achieve the aim of this study, the following research question was asked:

What are the views of witnesses and staff members about the experiences and challenges facing children whose parents are admitted into the witness protection programme?

BACKGROUND

The witness protection programme in South, called the Office of Witness Protection (OWP), was established in 1999 in terms of the Witness Protection Act 112 of 1998 (RSA, 1998). The protection of witnesses plays a pivotal role in the criminal justice system's quest to fight crime, as a witness's testimony is a necessary part of the fact-finding process of the court and links the perpetrator to the committed crime (Beqiri, 2018). The aim of witness protection programmes was initially to take care of the physical safety of the witnesses in order to dismantle organised crime and not much consideration was given to the impact of admission on the children of witnesses (Kiprono, Mwangi & Ngetich, 2015). This resulted in isolation and the separation of parents from their children, as well as stress and anxiety for both parents and children. According to Coley and Kull (2016), separation and social uprooting undermine emotional bonds, social skills, and cognitive, social and emotional functioning, and also impedes the school performance of children.

Witness protection programmes across the world have resolved to improve services to witnesses by extending admission to family members of witnesses, including children (Kayuni & Jamu, 2015). While there has been a shift and families are now allowed to go into the programme with witnesses, evidence from practice shows that children continue to experience separation, as some family members are unable to go into the programme because of commitments such as employment. In instances where, for example, the mother goes into the programme and the father does not, children are forced to stay with one parent, either in the programme or at home. This is because anyone who enters the programme is expected to terminate their employment, with no prospects of getting another job while in the programme or upon disengagement from the programme (Kaur, 2011). Furthermore, it is evident from practice that children lose out on school contact time when the family is removed from home urgently, and school reports and transfers are only obtained at a later stage. This causes delays in securing the placement of a child in a new school.

It is important that the witness protection programmes provide support services that enable family preservation. The Revised White Paper on Families (RSA, 2021) emphasises the importance of preserving families through interventions that capacitate and strengthen the family, including ensuring that children are raised within a supportive home environment and are afforded the right to a family. Families who are under protection are provided with support through what is commonly known as the witness assistance programme, which is a programme intended to support the witnesses and their families cope and adjust better in the programme, help witnesses heal from the trauma induced by witnessing a crime, empower witnesses to deliver effective testimony in court, avoid the secondary victimisation of witnesses, reduce the anxiety of participating in a trial, and work with the family of the witness at home to ensure successful family reunification and community integration when the witness is finally discharged from the programme (Dulume, 2017). Such services include providing psycho-social services, access to medical care and support with the educational needs of children, skills development and rehabilitation, as well as assisting witnesses to prepare for court (UNODC, 2008).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach within the framework of the exploratory, descriptive and contextual research designs was used in this study to gain an in-depth understanding of the views of witnesses and staff members on how children experience and cope with the admission of their parents into the witness protection programme (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Permission to conduct the study was granted by the OWP and ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Department of Social Work at the University of South Africa (UNISA). A collective instrumental case study was used to direct the selection of the sample and it also enabled the researcher to collect data from four groups of participants (Lichtman, 2014). The target population for this study was witnesses, protectors, social workers and senior managers in the witness protection programme in South Africa.

Participants were selected by means of non-probability, purposive sampling with the assistance of gatekeepers (Creswell & Poth, 2018). The criteria for inclusion focused on both male and female participants who were in the programme for three years or longer, who were fluent in English, and who were willing to participate in the study. In terms of the selection of witnesses, only witnesses with whom the researcher had not had any prior contact in the line of duty as a social worker were considered. The reason for this was to ensure that the information provided by the participants is not prejudiced by any existing work relationship with the researcher. The witnesses were made aware that the study is part of the requirement to obtain a PhD qualification at UNISA and that there was no direct or immediate benefit for taking part in the study. A colleague within the OWP was on standby to provide counselling to participants who could have been traumatised by answering the interview questions (Marshall & Rossman, 2016). However, the service was not utilised as there were no incidents of trauma.

The gatekeepers were the provincial managers of the witness protection programme. The sample was drawn from six provinces, namely: Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Northern Cape. Data were collected from 12 witnesses, 12 protectors, 3 social workers and 3 senior managers in the witness protection programme in South Africa (Koerber & McMichael, 2008). Protectors are the officials who are tasked with the responsibility of ensuring the physical safety of witnesses and their families. The entire population of social workers consisted of four social workers nationwide, including the researcher, while senior management consisted of three officials. Senior managers are non-social workers who are part of the leadership of the programme and are also responsible for decision making in the programme.

The interview schedule was tested by means of a pilot study that was conducted with two participants, namely one staff member and one witness, in order to ensure that the questions yielded sufficient information (Marshall & Rossman, 2016). Data were collected through the use of semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with an interview schedule (Tracy, 2013). A consent form was signed prior to data collection. The interviews with participants were digitally recorded and transcribed, and the data were analysed using the eight steps of data analysis constructed by Tesch (Creswell, 2009). Witnesses were individually interviewed in their safe houses and staff members were interviewed separately in their offices. The hard copies of data were kept in a safe within a strong room and soft copies were password protected on a computer (Wahyuni, 2012). Data were managed in terms of the Minimum Information Security Standards (rSA, 1996).

The service of an independent coder was employed to consolidate the themes, subthemes and categories. Data verification was guided by the principles of trustworthiness, namely credibility, dependability, transferability and conformability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The researcher also conformed to the ethical requirements for obtaining permission to conduct the study, i.e. obtaining consent, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, ensuring beneficence, and avoiding deception, as well as managing information and debriefing the participants (Bless, Higson-Smith & Sithole, 2013).

The researcher's conviction is that the outcomes of this study will help to improve the wellbeing of children whose parents are admitted to the programme and contribute to service delivery improvement in the OWP (Shaw & Holland, 2014).

Participants

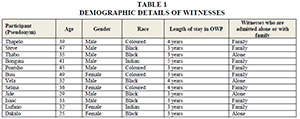

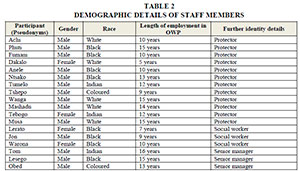

The demographic details of the participants are presented in Table 1 and Table 2 below.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory was used to interpret the research results because it emphasises the importance of the environmental system on a child's development (Ettekal & Mahoney, 2017). The environment, whether at the level of the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, or chronosystem, may be supportive of or detrimental to a child's development. It is important to note that the nature of the witness protection programme directly and indirectly marginalises children as a result of isolation, social uprooting, restrictions on movement, and lack of contact with family and social networks. Children are negatively affected when they are removed from their homes and placed into unfamiliar environments without social networks. At a microsystem level, children are detached from the environment to which they are accustomed, including family and friends, and are expected to adjust to an unfamiliar environment. Once in the programme, the mesosystem becomes complicated, as they are placed in a new schooling environment with a different academic programme, new teachers and a different teaching system. The impact of the exosystem can be seen when parents quit their jobs in exchange for their safety and children are indirectly affected, as parents are no longer in a position to provide in the same way as they did before being admitted into the programme. The macrosystem, in this context, involves the rules and laws that govern the witness protection programme which childre are expected to abide by, such as being unable to disclose their identity and location, and not being allowed to maintain contact with family members who are outside the programme. In terms of the chronosystem, children suffer the impact of separation and social uprooting and, although they are not directly involved with the criminal justice system as witnesses, the children are exposed to possible trauma that could have a long-term effect on their development and functioning later in life.

The ecological perspective was not only useful in the interpretation of the research results, but also provides a framework for the development of relevant and responsive psychosocial interventions by social workers in addressing the needs and challenges experienced by children whose parents are admitted to the programme.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Five themes emerged from the data analysis and will be presented in the next section. These themes are: the inability of children to adapt to the programme; children experience loneliness; manifestation of behavioural problems; family contact is required to help children to deal with separation; and social work intervention is required to help children to cope.

Theme 1: The inability of children to adapt to the programme

The participants made reference to the inability of children to adapt to the programme after being uprooted from their familiar environments. Participants reported that children in the programme struggle to adapt to the new school environment, especially if the medium of instruction and curriculum differ from what the child is familiar with. It was also reported that one of the children was unhappy and threatened to commit suicide because she was forced to repeat Grade 11, as the subjects offered by the new school differed from the ones she had been doing at home and she could not be placed in Grade 12.

Another reason is the language barrier, for example, a person from Cape Town might struggle with languages in Mpumalanga, it is also not easy for children to adapt in school. We had a child who wanted to commit suicide because of anger of having to repeat a grade that she had passed. OWP does not have a programme that caters for the needs of the minors. I think it is a nightmare for children who are admitted in the programme. I think the programme is not conducive for children and young adults because they need a support system. It is also hardfor parents who are admitted on the programme without their children. Some parents end up leaving the programme because children are unhappy. (Warona)

Ruff and Keim (2014) state that social uprooting leads to school transitions, which may in turn cause a delay in the transfer of school records, missing out on crucial topics in certain subjects, academic weakness, and in some instances a need to repeat grades. The participants also reported that the unhappiness of children often leads to some witnesses resigning from the programme prematurely. By going back home, witnesses run the risk of being silenced by the perpetrators. It was reported that children who are with their parents in the programme miss their family and friends at home, while those who are left at home are also not coping with being separated from their parents.

Because of the pressure from children, some witnesses would just leave the programme and go back home. Some would even leave the safe house without following a proper procedure. (Tumelo)

The thought of leaving the programme has crossed my mind. It is hard for me to be away from my children. I am even scared to phone home because they always ask when am I coming home, they want to visit me over the school holidays. (Thapelo)

According to the UNODC (2008), children are the most difficult group to protect, as they do not appreciate the extent of the threat that the family faces and thus struggle to assimilate into the new environment. Research shows that children, more so than adults, find it difficult to adjust in the programme, struggle to make new friends and to fit into the new schooling environments, and are often unable to cope with feelings of homesickness (Beune & Giebels, 2013; Council of Europe, 1999). Lu, Yeung, Liu and Treiman (2019) state that for children who are left at home, parental absence has a detrimental impact on their development, such as the lack of a stimulating homely environment. This in turn destabilises affectional relationships and leads to feelings of abandonment and insecurity. Such children go through vital stages of life without parental guidance and supervision.

Theme 2: Children experience loneliness

The participants indicated that children experience loneliness because of being moved away from their friends and family, and they find it difficult to successfully establish and maintain new friendships because of the strict rules of the programme.

My son had friends in school, but he never invited them to visit him here in the safe house because it is against the rules of the programme. It is difficult to teach a child to keep a secret or lie; he is really struggling, this is a new experience for him. (Selina)

It is overwhelming for children to have to carry a secret and live in constant fear of slipping up and saying something that could reveal their real identity. According to the UNODC (2008), children tend to lack the ability to function in a covert environment and find comfort by confiding in friends. However, in so doing, they reveal personal information to friends that might result in the safety of the family being compromised.

This frustrates children because they cannot contact their friends and grandparents. It also puts a strain on our marriage when the children are not happy. (Pontsho)

As for my children, Ifeel it would be better if they could speak to our family back home or their grannies. They miss family and it is difficult for them, physically, mentally, and emotionally it is a challenge for my children. (Busi)

Kaur (2011) states that isolation results in boredom and loneliness. English and Worlton (2017) reveal that there is a direct link between social uprooting and stress and anxiety in children. Kwan, Gitimoghaddam and Collet (2020) indicate that loneliness may cause health problems, both physically and psychologically, with an increased risk of depression and suicide in children. Furthermore, the study found a correlation between loneliness in childhood and child development challenges, learning difficulties, low self-esteem, lack of optimism, and poor health later in life. Hendrick (2009) states that the breakdown of social connections and the discontinuation of familiar activities, such as participation in sport, may lead to psychological distress for children. According to Kwan et al., (2020:17), "belonging is a basic human need" that relies on social attachments and interaction without which affected individuals experience social isolation and social exclusion. Fyfe and McKay (2000) hold the view that while it is necessary to remove witnesses from immediate danger and place them into the programme, it does little to allay feelings of anxiety about separation, especially for children.

Theme 3: Manifestation of behavioural problems

Participants raised concerns about behavioural problems displayed by children as a result of being admitted into the programme. Behavioural problems that were mentioned include disruptive behaviour at home, such as refusing to go to school, mood swings, and constantly picking fights with a parent or sibling. It was also reported that some children's school performance had declined since being admitted into the programme.

I have noticed that my 14-year-old daughter started to be rebellious now, and I don't know if it is because of being on the programme. I don't want our being on the programme to affect her negatively; she was not like this before we came here. (Bongani)

I am already having a big problem with my elder son, he is swearing at me, he wants to fight with me. I drag him out of bed in the morning to go to school. My children don't understand why I am testifying against their father. My son want to leave the programme, he even ran away from the safe house at some point. (Lufuno)

Sometimes my children just cry at night because they miss their grannies back home. As a father I don't have answers to the questions that my children ask. For example, how do I explain to a nine-year-old when she ask 'when are we going to see granny again?'. It is difficult for us. (Jide)

This finding is supported by Kaur (2011), who states that children, unlike adults, struggle to verbalise their frustrations and adapt to unfamiliar environments, which leads to emotional outbursts. According to Melrose (2013), moving homes results in relocation stress syndrome, a psychosocial and physiological disturbance caused by transfer from one environment to another. The symptoms in children include feelings of insecurity, lack of trust, loneliness, anxiety, attachment challenges, etc. Hendrick (2009) states that the children of witnesses often feel ignored, with no one to communicate with at home. Parents are swamped with various activities, including trying to adapt to the new environment and preparing to deliver their testimony in court, and thus pay less attention to the feelings of the children, leading to child-parent conflict.

On the other hand, Fegert, Diehl, Leyendecker, Hahlweg and Prayon-Blum (2018) state that isolated parents experience heightened irritability, stress and anxiety, which contribute to parent-child relationship problems, with the impact on children being internalised psychological distress. Fegert et al., (2018) further assert that affected children are sometimes perceived as defiant and rebellious by parents, who often respond with various forms of punishment. According to Ruff and Keim (2014), family relocation also results in children feeling resentment and anger towards their parents, as they blame them for having been removed from their social networks.

Theme 4: Family contact is required to help children to deal with separation

In order to mitigate the impact of social uprooting and separation on children, participants suggested interventions by social workers and stressed the importance of ensuring that children are able to keep contact with their family members who are outside the programme.

My children keep asking when are we going home. I can see that they are homesick and they just can't take it anymore; they miss home. Why can't OWP allow us to visit our family? Every year when I make a requestfor a family visit, I get a response saying O WP does not have money. When they admitted us here, they promised that we will be able to visit our family, now they have changed. (Isaac)

Sometimes children and parents blame each other for being on the programme. The children need psychological support to cope on the programme, otherwise social workers could motivate that witnesses must be allowed to see their families in order to avoid emotional breakdowns. It's not easy especially for children. (Fumani)

The witness feel guilty because he is not there to see his children who are not on the programme. On a yearly basis witnesses can apply for a family visit; we, however, have financial constraints at the present moment as far as this is concerned. Family visit has a positive effect on the witness; a witness will be in a positive spirit after seeing his children. (Tom)

Contact with family members outside the witness protection programme is facilitated by the programme through shielded video-link communication or physical meetings in safe locations, far from where the witness is protected, in order to ensure that the identity and location of protected witnesses are not compromised (Mack, 2014). However, it appears that physical contact does not take place often, as the OWP is reportedly experiencing financial constraints, leading to separation and frustration for witnesses and their children. The importance of witnesses maintaining contact with family members while in the programme is supported by Bakowski (2013) and Mack (2014). Deprivation of social contact and the lack of formal family contact are likely to tempt witnesses to break the rules of the protection agreement by initiating unsafe contact with their families (Beune & Giebels, 2013). A study by Koedam (1993), for example, revealed that a woman in the Witness Security Program (WITSEC) who had left her young child in the custody of her mother compromised her safety by contacting her family, as she could no longer bear the thought of her child growing up without her. Family contact helps children to cope and adjust better in the programme (Lu et al., 2019). Stepakoff, Henry, Barrie and Kamara (2017) emphasise that the maintenance of human connections is also vital in order to recover from trauma.

Theme 5: Social work intervention is required to help children to cope

Participants indicated that children would benefit from social work interventions that help them deal with the challenges associated with separation and social uprooting, and cope with their parents being away, as well as in order to help them to better assimilate into the covert environment.

Being in OWPfrustrates my children a lot. We can't live a normal life because there are things that we are not allowed to do. Ifeel that my children need a social worker just to help ease their mind. (Steve)

I think the social worker must visit the witnesses on a monthly basis to check how the family is doing and to see if the children are coping. Maybe I shout at my children and traumatise them. Maybe OWP does or says something to upset me and I end up shouting at my children. (Vela)

Sometimes my children cannot speak to me because I could be [too] stressed and irritated to listen to them. That is why we need social workers to intervene. It will be nice if we could be able to reach a social worker at any time. Going through a protector and making an appointment, sometimes it takes too long as protectors often go away. We are not saying you must come every month, but regularly. (Dakalo)

According to Ruff and Keim (2014) and Coley and Kull (2016), psychosocial support is necessary to assist children with social, emotional, academic and adaptation difficulties and homesickness, as well as to help the children to develop to their maximum potential. Such intervention may include counselling, therapy, access to healthcare, strengthening parenting competencies, and the establishment of social support and networks (Fegert et al., 2018). According to Lakshmi (2014), social workers' interventions are not only meant to address social problems, but also to define these problems as they are agents of social change by linking social science, policy and evidence-based practice. Getz (2012) states that children are vulnerable and are more likely to be affected by traumatic incidents. However, with timeous and effective therapy, combined with the right parenting support, they can recover.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The author intended to gain an understanding of how the children of witnesses, whether in the programme with their parents or staying at home, cope with their parents being admitted into the programme. This was done by conducting 30 interviews with witnesses, protectors, social workers and senior managers in OWP. The views of witnesses as the parents of these children were corroborated by those of staff members. The participants stated that children who are admitted into the programme experienced difficulties in coping with being isolated from their family and friends. Separation from family and friends and the social uprooting of children resulted in feelings of loneliness. Loneliness resulted in children presenting with behavioural problems, which in turn affected the parent-child relationship. Some of the behaviour reported included being rebellious, fighting with parents, refusing to go to school, absconding from the safe house, and insisting on going back home regardless of the threat to the family. Children experienced challenges such as difficulties in establishing new social networks and in adjusting to the new schooling environment, mainly because of differences in the medium of instruction and academic programme of the new school, which led to poor academic performance.

Participants also reported that children who are left at home with grandparents or the extended family experienced difficulties in coping without their parents. Witnesses also shared their frustration at the thought of their children growing up without their parental guidance, resulting in some witnesses abandoning the programme in order to be reunited with their children. The challenge of withdrawing from the programme is that witnesses have to face the perpetrators of the crime on their own without protection. Furthermore, witnesses also experienced heightened levels of anxiety, as they struggled to make sense of their lives in new and unfamiliar environments without social support. Participants found the lack of regular and consistent family contact difficult to cope with, especially the children, as they could not contact their grandparents or cousins or visit them.

Therefore, consistent with the findings presented in this paper, the following recommendations are made.

• The OWP should consider encouraging the witnesses to be admitted into the programme along with their family, especially children, in order to prevent the children's feelings of isolation and to ensure family preservation. This can be achieved by creating awareness of the programme and how the programme functions in communities, so that witnesses who come into the programme have an idea of what to expect. Awareness programmes could be presented by OWP social workers in collaboration with social workers from both the Department of Social Development and the South African Police Service.

• The social workers in OWP should consider developing and providing intervention programmes that are child-friendly and aimed at addressing the needs of children who are admitted into the programme with their parents. Among other things, such programmes should help children to adjust in the programme and at school, and link children to recreational activities within the community where their family is protected. This will help the children to meet potential friends and help to avoid boredom and loneliness.

• Ensuring the implementation of consistent family contact between witnesses and their children will reduce the likelihood of witnesses abandoning the programme with the intention of reconnecting with family. Children who are left at home should also be provided with psychosocial services to help them cope and better understand the reasons for their parents' absence. These services could be rendered by social workers in OWP as part of family preservation.

Admission of parents into the programme indeed interrupts family functioning, places stress on emotional bonds, and generally impacts negatively on the lives of children. However, it is hoped that the availability of knowledge and understanding of how children experience the admission of their parents into witness protection programmes, as presented in this study, will enable social workers to come up with interventions that will help children to manage the trauma that comes from their parents being admitted into the programme and ultimately restore, reunify and preserve families.

REFERENCES

BĄKOWSKI, P. 2013. Witness protection programmes: EU experiences in the international context. [Online] Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/LDM_BRI(2013)-130408 [Accessed: 2017/05/02]. [ Links ]

BEQIRI, R. 2018. The immediate demand for an efficient protection of witnesses of justice in Albania. RAIS Journal of Social Sciences, 2(1): 25-48. [ Links ]

BEUNE, K. & GIEBELS, E. 2013. The management of protected witnesses: a behavioural perspective. [Online] Available: https://www.utwente.nl/en/bms/pcrv/publications-and-reports/witness%20protection/management-of-protected-witnesses-beune-giebels-english.pdf [Accessed: 2019/02/21]. [ Links ]

BLESS, C., HIGSON-SMITH, C. & SITHOLE, L.S. 2013. Fundamentals of social research methods: an African perspective. 5th ed. Cape Town: JUTA. [ Links ]

COLEY, R. L. & KULL, M. 2016. Is moving during childhood harmful? Multiple residential moves take a toll on children, but the effects may fade with time. Policy Research Brief. [Online] Available: https://www.macfound.org/media/files/hhmbrief-ismovingduringchildhoodharmful2.pdf [Accessed: 2021/04/15]. [ Links ]

COUNCIL OF EUROPE. 1999. Report on Witness Protection (Best Practice Survey). [Online] Available: https://www.coe.int/t/dg1/legalcooperation/economiccrime/organisedcrime/BestPractice1E.pdf [Accessed: 2018/08/19]. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. 2009. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. United Kingdom: SAGE. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. & POTH, C. N. 2018. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. United Kingdom: SAGE. [ Links ]

DEMIR, M. 2018. The perceived effect of a witness security program on willingness to testify. International Criminal Justice Review, 28(1): 62-81. [ Links ]

DULUME, W. 2017. Ethiopian witness protection system: comparative analysis with UNHCHR and good practices of witness protection report. Oromia Law Journal, 6(1): 124-150. [ Links ]

ENGLISH, A. S. & WORLTON, D. S. 2017. Coping with uprooting stress during domestic educational migration in China. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 11(e9): 1-10. [ Links ]

ETTEKAL, A. & MAHONEY, J. 2017. Ecological Systems Theory. In: PEPPLER, K. (ed). The SAGE Encyclopaedia of Out-of-School Learning, [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483385198.n94 [Accessed: 2021/12/03]. [ Links ]

FEGERT, J. M., DIEHL, C., LEYENDECKER, B., HAHLWEG, K. & PRAYON-BLUM, V. 2018. Psychosocial problems in traumatised refugee families: overview of risks and some recommendations for support services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12(Art. 5): 1-20. [ Links ]

FERY, I. 2012. Executive summary of a study on the protection of victims and witnesses in D.R. Congo. [Online] Available: https://www.protectioninternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/PI-Summary-Victims-Witnesses-protection-study-DRC-3.08.2012-EN1.pdf [Accessed: 2019/04/21]. [ Links ]

FYFE, N. R. & MCKAY, H. 2000. Desperately seeking safety: Witness's experiences of intimidation, protection and relocation. The British Journal of Criminology, 40(4): 475-691. [ Links ]

GETZ, L. 2012. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy - hope for abused children. Social Work Today, 12(3): 22-36. [ Links ]

HENDRICK, B. 2009. Uprooting children raises their suicide risk: The stress of a family move may have dire consequences on kids. [Online] Available: https://www.webmd.com/depression/news/20090603/uprooting-children-raises-their-suicide-risk [Accessed: 2021/04/15]. [ Links ]

KARIRI, N. J. & SALIFU, U. 2016. Witness protection: facilitating justice for complex crimes. ISS Policy Brief 88. [Online] Available: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/policybrief88.pdf [Accessed: 2017/04/30]. [ Links ]

KAUR, S. 2011. Potential challenges in a witness protection programme in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 19(2): 363-368. [ Links ]

KAYUNI, S. W. & JAMU, E. 2015. Failing witnesses in serious and organised crimes: Policy perspectives for witness protective measures in Malawi. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 41(3): 422-438. [ Links ]

KIPRONO, W., MWANGI, W. & NGETICH, K. 2015. Witness protection: Socio cultural dilemmas. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology, 2(10): 50-58. [ Links ]

KOEDAM, S. W. 1993. Clinical considerations in treating participants in the Federal Witness Protection Program. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 21(4): 361-368. [ Links ]

KOERBER, A. & MCMICHAEL, L. 2008. Qualitative sampling methods: a primer for technical communicators. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22(4): 454-473. [ Links ]

KWAN, C., GITIMOGHADDAM, M. & COLLET, J. 2020. Effects of social isolation and loneliness in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: a scoping review. Brain Science, 10(11): 1-31. [ Links ]

LAKSHMI, J. 2014. Role of school social workers in dealing with problems of adolescents: a mental health perspective. Indian Journal of Applied Research, 4(12): 172-174. [ Links ]

LICHTMAN, M. 2014. Qualitative research for the social sciences. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

LINCOLN, Y. S. & GUBA, F. A. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

LU, Y., YEUNG, J. W., LIU, J. & TREIMAN, D. J. 2019. Migration and children's psychosocial development in China: when and why migration matters. Social Science Research, 77(1): 130-147. [ Links ]

MACK, R. L. 2014. The Federal Witness Protection Program revisited and compared: Reshaping an old weapon to meet new challenges in the global crime fighting effort. University of Miami International & Comparative Law Review, 21(191). [Online] Available: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umiclr/vol21/iss2/4 [Accessed: 2020/04/21]. [ Links ]

MAHONY, C. 2010. The justice sector afterthought: witness protection in Africa. [Online] Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2781181 [Accessed: 2017/04/30]. [ Links ]

MARSHALL, C. & ROSSMAN, G. B. 2016. Designing qualitative research. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

MELROSE, S. 2013. Relocation stress: how staff can help. Canadian Nursing Home, 24(1): 16-20. [ Links ]

MERRIAM, S. B. & TISDELL, E. J. 2016. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

MUJKANOVIC, J. 2014. Development of a witness and victim support system - Croatian experience: good practices and lessons learned. [Online] Available: https://www.eurasia.undp.org/content/rbec/en/home/library/democraticgovernance/development-of-a-witness-and-victim-support-system.html [Accessed: 2020/07/15]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1996. Minimum Information Security Standards. [Online] Available: https://www.sita.co.za/content/minimum-information-security-standards [Accessed: 2017/08/11]. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 1998. Witness Protection Act, No 112 of 1998. Government Gazette, Vol. 401, No. 19523. 27 November 1998. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2021. Department of Social Development. Revised White Paper on Families in South Africa. Notice 540 of 2021, Government Gazette, Vol. 586, No. 44799. 2 July 2021. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RUFF, S. B. & KEIM, M. A. 2014. Revolving doors: the impact of multiple school transitions on military Children. The Professional Counsellor, 4(2): 103-113. [ Links ]

SHAW, I. & HOLLAND, S. 2014. Doing qualitative research in social work. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

STEPAKOFF, S., HENRY, N., BARRIE, N. B. & KAMARA, A. S. 2017. A trauma-informed approach to the protection and support of witnesses in international tribunals: ten guiding principles. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 9(2): 268-286. [ Links ]

TRACY, S. J. 2013. Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. London: John Wiley. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME (UNODC). 2008. Good practices for the protection of witnesses in criminal proceedings involving organised crime. [Online] Available: https://www.unodc.org/documents/middleeastandnorthafrica/organised-crime/Good_Practices_for_the_Protection_of_Witnesses_in_Criminal_Proceedings_Involving_OrganizedCrime.pdf [Accessed: 2017/05/02]. [ Links ]

WAHYUNI, D. 2012. The research design maze: understanding paradigms, cases methods and methodologies. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research (JAMAR), 10(1): 69-80. [ Links ]