Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.58 no.2 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/58-2-1037

ARTICLES

Towards the creation of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe: an inside perspective on the Department of Social Development

Mr Wilberforce KurevakwesuI; Mr Fanuel DzomaII; Dr Mulwayini MundauIII; Mr John Chiwanza MagochaIV; Mr Simbarashe ChizasaV; Mrs Mary TakangovadaVI

IDepartment of Social Work, Women's University in Africa, Bulawayo Campus, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. wilberkureva90@gmail.com

IIProvincial Social Development Officer, Department of Social Development, Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, Bulawayo Metropolitan Province, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. dzomafanwell@gmail.com

IIIDepartment of Social Work, University of Zimbabwe, Mount Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe. lmundau@gmail.com

IVDepartment of Social Work, University of Zimbabwe, Mount Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe. joemagocha112@gmail.com

VGraduate Intern, Department of Social Development, Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, Manicaland Province, Mutare, Zimbabwe. chizasasimbarshe@gmail.com

VISocial Development Officer, Department of Social Development, Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, Compensation House, Harare, Zimbabwe.marytakangovada1@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

In June 2020 the government of Zimbabwe issued a statement of intent towards embracing a developmental social welfare approach by changing the name of the Department of Social Welfare to the Department of Social Development. This has been a long-awaited move in the indigenisation of Zimbabwe's social welfare services. However, despite such a strong and progressive commitment by the government, there is no clear framework on how the Department of Social Development plans to implement developmental social welfare services in Zimbabwe. It is this concern that we address as we take an 'inside perspective' on the work of the Department of Social Development towards explicating current programmes and services, and examine available information on how the Department intends to reorientate Zimbabwe's social welfare system. We then offer recommendations that can be used by the DSD towards the creation of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: developmental social welfare, Department of Social Development indigenisation, social welfare, welfare state, social welfare services, Zimbabwe

INTRODUCTION

The focus of this article is on the creation of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe. The department responsible for the provision of social welfare services in Zimbabwe - the Department of Social Development (DSD) - has been providing services on a remedial and residual basis ever since it was instituted in colonial times. However, in June 2020 the DSD issued a strong statement of intent towards the adoption of a developmental stance to the provision of social welfare services by changing its name from the Department of Social Welfare to the Department of Social Development (DSD). But after this development, no clear framework has emerged to map out how this approach will be implemented outside the provisions of the National Social Protection Policy Framework (NSPPF) (MoPSLSW, 2016), which has a developmental inclination. It is against this background that we seek to explore the current position of the DSD - the programmes and services being offered - and how the DSD intends to implement a developmental approach to the provision of social welfare services, and come up with practicable policy and practice recommendations. Given the fact that the government's commitment to offer development-oriented social welfare services is very recent, we adopted an inside perspective in that our own experiences, knowledge and work within the DSD have informed this article. We believed there were few better ways to gain more insights than the 'inside perspective' that we adopted.

As such, the article begins with an exposition of the inside perspective that we adopted in this study, followed by a brief account of the historical background of the DSD and an analysis of the application of developmental social welfare principles in other jurisdictions. After that, the programmes that are being implemented by the DSD are clarified in an attempt to explain, through the inside perspective, how developmental social welfare will be implemented by the DSD in Zimbabwe. We then offer policy and practice suggestions for the DSD.

THE INSIDE PERSPECTIVE

The 'inside perspective' that we adopted refers to the authors being part of the DSD and the analysis provided reflects the views of those 'inside' or working within the DSD. This contrasts with Spitzer's (2019: 568) "mzungu perspective", which refers to a self-reflective outsider's view. Considering that the DSD was rebranded a few months before the writing of this article, an inside perspective was needed towards understanding the means through which the developmental social welfare approach will be implemented by the DSD. An inside perspective also ensures that the policy and practice recommendations offered by the authors are valid and relevant to the work of the DSD. To further support the use of an inside perspective, during the time of writing this article all the authors, except for two, were working within the DSD. Of the six authors, two have more than 15 years' experience within the DSD - at management level. The other two were conducting their Master of Social Work fieldwork within the DSD. Of the two authors not working within the DSD, one is a researcher who has strong interest in issues around developmental social welfare and he has supervised many BSW and MSW students during their fieldwork within the DSD, and the other one once did his MSW fieldwork within the DSD and he has also supervised several BSW and MSW students within the DSD. Given this, all the authors could adopt an inside perspective, though to some the extent to which they could assume an inside perspective was limited. The inside perspective in this article is a reflective one; it critically reflects upon developmental social welfare realities within the DSD. Its basic philosophy - just as in Spitzer's (2019) mzungu perspective - is that such reflection should be a standard in social work research and practice.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE DSD

The DSD is housed under the government of Zimbabwe's Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare (MoPSLSW). The historical background of the DSD dates back to the colonial era. Kaseke (1998) documents that the first thrust to provide social welfare services in Zimbabwe took place in 1936, when the Probation and School Attendance Compliance Officer programme was introduced in the then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). A recommendation to institute probation services was made after the Ministries of Education, Justice and Home Affairs mutually investigated issues related to school attendance and non-attendance as well as children in conflict with the law (Kaseke, 1998). Probation programmes for white children were introduced in 1936 after F.S. Caley from Britain was employed as the first probation officer by the colonial government and it was around that time that education was made compulsory for white children (Kaseke, 1998).

In the beginning the system's main thrust was the welfare of the white minority. As for the native black African, the welfare system enacted a Vagrants Act, which was meant to regulate the flow of blacks into towns (Kaseke, 1998; Mupedziswa, 1988). In 1948 an appropriately organised Department of Social Welfare was established for the first time in Southern Rhodesia - since the Rhodesian government had secured the services of a probation officer from the United Kingdom (Mupedziswa, 1988). The Department's functions were somewhat limited in scope, but they included investigations of juvenile delinquency cases amongst all races. In 1949, however, the first black probation officer was appointed in the Department of Social Welfare (Kaseke, 1998).

In the 1950s and 1960s the Department gradually expanded throughout the country as it established offices outside Harare - in Bulawayo, Gweru, Mutare and other towns (Kaseke, 1998; Mupedziswa, 1988). In line with this expansion, the then government set up institutions such as, inter alia, Northcot, Highfields Probation Hostel, Luveve Training School for Girls and the Percy Ibbotson Probation Hostel for the rehabilitation of child offenders (Hampson & Kaseke, 1987; Mupedziswa, 1988). The Department introduced the public assistance programme in 1964 whereby assistance was provided through means testing, primarily within the residual model of social welfare. However, the public assistance programme was not that effective because after four years (1964-1968) fewer than four hundred black families were assisted at a time when hundreds of thousands of black families needed assistance (Hampson & Kaseke, 1987; Mupedziswa, 1988). One of the reasons for this was the racist tendencies of the then government which affected the effectiveness of its programmes, despite the Department expanding to several towns and cities.

The coming of independence from British colonial rule in 1980 saw the development of the Department to also become responsible for several programmes that were attached to other government ministries, non-governmental organisations and churches involved in welfare provision. This also saw the promulgation of new legislation as well as amendments to existing legislation that led to the provision of social welfare services to all deserving Zimbabweans - regardless of colour, race or ethnic background. Consequently, according to the Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ), social welfare services began to be administered in terms of the Government of Zimbabwe, Social Welfare Assistance Act of 1988.

Since the 1980s the DSD has been rebranded time and again, from the Department of Social Welfare to the Department of Social Services (together with the Department of Child Welfare and Probation Service)1, then back to the Department of Social Welfare, and since June 2020 it is known as the Department of Social Development. This change of name to indicate a developmental orientation is a statement of intent by the government towards embracing developmental social welfare in line with the government's National Development Strategy 1 which runs from 2021 to 2025. However, despite this change of name, social welfare services provision has to date remained residual and remedial instead of being developmental and preventive. In the light of the need to set the stage for the government to develop a comprehensive framework for developmental social welfare in Zimbabwe, the analysis that we offer in this article is highly warranted. To make the analysis possible, we had to thoroughly conceptualise the notion of developmental social welfare and review the literature from other jurisdictions that have successfully implemented the approach.

CONCEPTUALISING DEVELOPMENTAL SOCIAL WELFARE

Traditionally, there are four welfare-state regimes and these relate to the liberal, social democratic, corporatist and state-socialist welfare states (Hassim, 2006). However, in the past three decades, a new welfare regime appeared - the developmental welfare state. This welfare regime has been seen by several scholars as one that can rival remedial social welfare provision by addressing root causes of social problems throughout Africa (Kurevakwesu, 2017; Manyama, 2018; Ntjana, 2014; Patel, Triegaardt & Noyoo, 2005; Spitzer, 2019). Gil (1999) saw developmental social welfare as a solution to the challenges affecting social welfare throughout the world - a view that is also shared by Manyama (2018). Since developmental social welfare derives from the social development approach, it is prudent to first define social development. Kaseke (2001) argues that social development - as a term and philosophy - was born out of a conceptualisation of development that was skewed more towards economic growth and development. But the reality is that economic development does not equally translate to overall development. Given this, there was need for an approach that would emphasise the value of social factors in development (Kaseke, 2001; Mupedziswa, 2001).

Social development has been defined in several ways by several scholars. To Dominelli (1997), it is a process through which resources and human interactions are organised towards improving the capacities of all people to realise their full potential. Midgley (1995:25) perceives it as "a process of planned social change designed to promote the well-being of the population as a whole in conjunction with a dynamic process of economic development". These definitions - though overtaken by events - are as relevant as they were during their day in defining social development. Midgley and Pawar (2017) provide a somewhat more recent and comprehensive definition of social development as they summed up all definitions that have so far been given into three classes. In line with the three classes of definitions provided by Midgley and Pawar (2017), social development relates to the organisation and association of both social and economic development, institutional and social transformation, and the enhancement of capabilities of people, their freedom, and satisfaction of their needs and improvement of quality of life.

Developmental social welfare is defined as a welfare-sector approach that focuses on bringing about social development through promotion of the socio-economic inclusion of the poor by focusing on their strengths and capabilities, so that they become self-reliant and independent towards improvement in their quality of life (Ntjana, 2014). Dutschke (2009) defines a developmental social welfare system as one that tries to concomitantly bring about both economic and social development - an explanation that is challenged by Midgley and Pawar (2017), as they see it as a misconstruction to take social and economic development as binary forms of development since social development inherently includes economic development. Nevertheless, Dutschke (2009) provides important aspects that reflect a developmental social welfare system. Dutschke (2009) argues that a developmental social welfare system invests much of its resources in the prevention of social problems and that government departments must collaborate to make a developmental state possible. Additionally, if prevention of social problems fails, early intervention services are offered as soon as a social problem appears, and this guards against costly later interventions if the problem is left to grow - something that brings about holistic development (Dutschke, 2009).

In the final analysis, it can then be argued that a developmental welfare regime is one in which there is, inter alia, the development of capacities of people, promotion of self-reliance, prevention of social problems and early intervention, a focus on the poor (alleviation of poverty and inequality), participation, improvement of quality of life, and collaboration between government departments. Despite there being a wealth of benefits in adopting a developmental welfare regime, what is worrying is that the uptake of the approach by most African governments is rather slow as shown in the following section.

LITERATURE ON DEVELOPMENTAL SOCIAL WELFARE IN AFRICA South Africa

Among African countries, one country that has successfully adopted a developmental social welfare model is South Africa, where developmental social welfare services have evolved since the adoption of the White Paper for Reconstruction and Development of 1994 and the White Paper on Welfare of 1997 (Lombard & Wairire, 2010; Patel, 2016). These were put in place to transform the colonial welfare system that was rigged towards the white minority by the apartheid regime (Lombard, 2019; Lombard & Viviers, 2021). After coming into power in 1994, the South African government began efforts to develop South Africa and to provide welfare towards social development in an attempt to redress the ills of the colonial past on South Africa's native society (Cassim, 2016; Lombard & Wairire, 2010; Lombard & Viviers, 2021). South Africa's Department of Social Development adopted the White Paper on Welfare, which situated developmental programmes and services at the heart of policy-making and intervention processes. One of the major goals of this White Paper was to foster socio-economic development through poverty alleviation. This was because poverty, unemployment and the problem of housing had become the prevailing afflictions for the majority of South Africans and the remedial approach could not respond effectively to these challenges (Lombard & Wairire, 2010; Patel, 2016).

To further strengthen the developmental approach adopted by South Africa's Department of Social Development they adopted the Integrated Service Delivery Model (ISDM) for the provision of developmental social welfare services in 2011 (RSA, 2011). Since then, the South Africa's Department of Social Development has strengthened its social development programmes - including community development and social security - towards addressing poverty alleviation. From 2011 onwards, social welfare in South Africa was conceptualised within the developmental approach. One of the programmes of the DSD - community development - began to be used towards combining the efforts of individuals, groups and communities to foster socio-economic development (RSA, 2011). The programme strives for the reorientation of the provision of social welfare services from the curative or remedial model towards the preventive social development approach. Moreover, the success of developmental social welfare in South Africa - through the 2011 framework - now rests upon the availability of social workers and other social service occupations that are adequately trained to apply strategies aimed at developing capacities, human potential and the empowerment of communities (RSA, (2011). As it stands, developmental social welfare services in South Africa are provided as a constitutional dictate by the DSD.

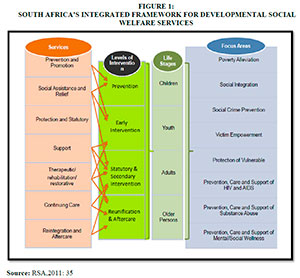

It is also noteworthy that the ISDM of 2011 mandates other government departments to adopt developmental social welfare approaches in their business so that the provision of such services becomes holistic (RSA, 2011). These departments include the Department of Basic Education, which is mandated by the framework to formulate, amend and apply policies, programmes and approaches that foster the extension of developmental social welfare services in South Africa's education sector. Other departments that were given the same mandate include the Department of Health, the Department of Correctional Services, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, the South African Police Service and all organisations that work on the welfare of women, children and people with disabilities (RSA, 2011). Among the directives are also the requirements that these departments should recognise social service professionals within their departments, develop referral systems to link vulnerable children with necessary resources, and commit resources towards the delivery of social welfare services that seek to promote child welfare in the various provinces of South Africa. Even South Africa's Cooperate Governance and Traditional Affairs Department - which is responsible for running municipalities - was given the same responsibility by the ISDM (RSA, 2011). The figure below sums up the integrative framework.

The levels of intervention for South Africa's ISDM include prevention, early intervention, statutory intervention or alternative care and residential care, together with reunification and aftercare (RSA, 2011). These levels are not in any defined successive form, as they do not follow any pattern. It is the developmental needs of communities together with the presenting social ills that determine the patterns of service delivery to be followed. In this way, the levels of functioning of beneficiaries are determined, together with the challenges they are facing and their specific needs, and from that point on interventions are developed towards improving functional levels and promoting self-reliance (RSA, 2011). These levels are explained in more detail below.

Levels of South Africa's Integrated Framework for Developmental Social Welfare Services Prevention

The focus of prevention is to build and fortify beneficiary capability, independence or self-sufficiency and resilience, whilst - at the same time - dealing with socio-economic and personal issues towards establishing an environment that is conducive to improving wellbeing (RSA, 2011). The major focus of service provision at this level is to reduce the expansion of development needs into risks and social problems.

Early intervention

Early intervention aims to prevent the development of social problems by identifying - at the earliest possible time - any risks, actions or signs from persons, social groups and social institutions (RSA, 2011). These have the tendency to affect the wellbeing of people and, if left to develop, they can trigger lifelong social problems that will continue to affect individual and societal development. For instance, there can be early detection of likely causes of crime and drug abuse, and these will have to be dealt with so that the likelihood of these social ills emerging is reduced (RSA, 2011).

Statutory or residential care and alternative care

Under this level of intervention, the economic, social and emotional status of service beneficiaries will be compromised (RSA, 2011). There will be a need to either apply statutory interventions or to move the beneficiary from their current disabling environment; this can help restore the normal functioning of beneficiaries or prevent the continued development of the problem. This can be referred to as tertiary prevention and it can also be rehabilitative.

Reunification and aftercare

At this level of service delivery, efforts are made to help service beneficiaries to become self-reliant and improve their functioning in a context that is conducive to this. There is also reunification with the family and reintegration of beneficiaries into society.

Challenges for developmental social welfare in South Africa

Despite having such a multifaceted integrative framework for developmental social welfare services, service delivery in line with this approach is not without challenges in South Africa (Ntjana, 2014; Patel, 2016). Some of the challenges include the lack of resources to support social welfare services provision (Alpaslan & Schenck, 2012), lack of understanding among social workers on what developmental social welfare entails (Lombard, 2007; Lombard, 2008; Ntjana, 2014), the shortage of social workers as a result of emigration (Cassim, 2016; Ntjana, 2014; Patel, 2016), together with poor working conditions for social workers (Ntjana, 2014; Patel & Hochfeld, 2008; Patel, 2016).

Despite these and other challenges, Lombard and Wairire (2010) argue that one of the factors that has aided the success of developmental social welfare in South Africa is the proper regulation of the social work profession. Correspondingly, in their recommendations for the Department of Social Development of South Africa, Lombard and Wairire (2010) argued that the regulation of the profession has to continue on a positive trajectory, because this will create a well-placed and knowledgeable unit of social workers that will improve the delivery of quality developmental social welfare services.

The East African Community and the rest of Africa

In other African countries, making provision for developmental social welfare services is evident in several pieces of legislation and socio-economic policies, but there are no formal structures for their implementation, for instance, in Kenya (Lombard & Wairire, 2010; Wairire & Kiboro, 2014). This is confirmed by Spitzer (2019), who used findings from a study by Twikirize, Spitzer, Wairire, Mabeyo and Rutikanga (2014) to show how countries in the East African Community2 have moved towards the adoption of developmental social welfare. In the study, however, it is clear that in the East African Community no country has made a formal commitment to transform social welfare services towards development. But individual social workers have taken it upon themselves to try and offer developmental social welfare services.

In the same study by Twikirize et al. (2014) social workers reported the extent to which their work resonated with the principles of developmental social welfare. In Kenya 52 percent of social workers who took part in the study reported that their work can be related to the provision of developmental social welfare (Twikirize et al., 2014). In Rwanda the percentage of social workers who reported this was 29 percent, whilst in Tanzania it was 18 percent and in Uganda it was 56 percent (Twikirize et al., 2014). However, Kalinganire and Rutikanga (2014) argued that developmental social welfare has become the privileged model for social work practice in Rwanda - something that speaks to the improved adoption of developmental social welfare practices in the country. In line with these statistics, the total percentage of social workers who adopted the principles of developmental social welfare in their work was 33 percent of all social workers who took part in the study in the four East African Community countries (Spitzer, 2019; Twikirize et al., 2014). This shows that the uptake of developmental social welfare in the region is poor, despite Kalinganire and Rutikanga's (2014) argument that it is the privileged model for social work in Rwanda.

Dlamini (2020) argues that in Eswatini the government has a development agenda that social workers subscribe to in assisting households that are affected by HIV/AIDS - using participatory approaches to end poverty and improve the social and economic wellbeing of people. Despite this, the Kingdom of Eswatini has not formally adopted a developmental social welfare approach. In Namibia there are calls for the government to formally adopt a developmental social welfare approach (Chiwara & Lombard, 2017), but to date the Namibian government has not done so. As for other African countries, the literature on developmental social welfare is scarce - signalling its non-existence or poor implementation. In Zimbabwe attempts to formalise the creation of a developmental welfare state were made in mid-2020, but there is no clear framework on how the approach will be implemented. However, some of the programmes offered by the DSD have - over the years - been gradually transformed towards developmental social welfare, whilst most of them are still remedial in nature (Kurevakwesu, 2017; Mhiribidi, 2010). Some of these programmes are explicated in the following subsection.

PROGRAMMES AND SERVICES OFFERED BY ZIMBABWE'S DSD

The DSD's work is guided by several pieces of legislation, including the Children's Act (Chapter 5:06), the Disabled Persons Act (Chapter 17:01), the Social Welfare Assistance Act (Chapter 17:06), the Private and Voluntary Organisations Act (Chapter 17:05) and several policies including the National Orphan Care Policy (GoZ, 1988; GoZ, 1991; GoZ, 1999; GoZ, 2001; GoZ, 2008). These pieces of legislation and policies have given rise to several programmes that are offered by the DSD towards assisting vulnerable groups - orphans and vulnerable children, the elderly, persons with disabilities, child offenders, families affected by drought and famine, and economic hardships, among others. Some of these programmes and other related services are elucidated below to provide a basis for the discussion that follows together along with viable recommendations.

Provision of maintenance allowance

The DSD provides monthly allowances to vulnerable households towards family support and helps the elderly and persons with disabilities. The programme is targeted at households and beneficiaries are means-tested by Social Development Officers (SDOs)3 with the DSD. Assistance through this programme is renewed annually - since the programme runs from January to December of each year -and if a person does not renew by way of filling an application form at the closest DSD district offices, there will be no payment.

Child protection (in need, custody, and adoption)

The DSD is mandated to provide care and support to vulnerable children or children in need of care as defined in the Children's Act (Chapter 5:06) (GoZ, 1991). As such, the DSD places children in various children's homes and discharges some when they turn 18 - or before they turn 18 for reunification with their relatives upon successful tracing or placement in alternative care. For children in institutions, the DSD pays school fees together with monthly per capita grants that have been pegged at ZWL4 $1 500 per child since January 2021 (an equivalent of less than USD $10 on the parallel market exchange rate, but close to USD $15 at the official exchange rate). The grants are reviewed from time to time - and they are currently under review. In cases where there is a custody dispute over a child and upon receipt of a case from the children's court, the DSD investigates the case and compiles a sociological report on the circumstances of the disputing parties and of the child(ren) and recommends to the court how best to deal with the case, or who between the disputing parties is suitable to have custody of the child(ren).

Juvenile justice (child offenders)

For child offenders, upon referral by the courts or the police, the DSD investigates and compiles a sociological report for the court or the Prosecutor General. The report is meant to assist the court to make an informed decision or judgement on the matter and pass an appropriate sentence. For child offenders below 14 years, the sociological report is compiled for the Prosecutor General, whilst for those above 14 years but below 18 years the report is compiled for the Criminal Courts, either the Magistrate's court or the High Court, depending on the nature and gravity of the offence committed by a child.

Assisted Medical Treatment Orders (AMTOs) - Health assistance

The DSD provides health assistance to vulnerable people who cannot raise money for treatment and medication. It assesses clients in need of health assistance and issues the AMTOs so that clients may access health services at any government or mission hospitals - free of charge. After that, upon receipt of claims from health institutions, the DSD processes claims for payment by the government.

The Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) - Education assistance

The DSD pays tuition and exam fees for orphans and vulnerable children at both primary and secondary school levels. Through this programme the DSD now provides uniforms and stationery to such disadvantaged children. In some cases, boarding fees are paid for vulnerable children with disabilities who require boarding facilities from Early Childhood Development level to Form 6. Community and school selection committees are responsible for the selection of beneficiaries. After selection, the DSD's district offices, together with District School Inspectors, verify the applications received from schools. The verified applications are then sent to the DSD head office, where payments are processed.

Registration and monitoring of PVOs, children's and old people's homes

The DSD's district and provincial offices process applications for the registration of private and voluntary organisations (PVOs), old people's homes and children's homes. The applications are then forwarded to the DSD head office for registration after review by a national PVO board, which is composed of experts from diverse fields. After registration, the DSD monitors, supervises and inspects the PVOs, old people's homes and childcare institutions and ensures that they abide by registration conditions and all legal instruments that govern their operations to promote quality service delivery.

Cash transfers

The DSD offers unconditional cash transfers to food-poor households. One of the cash transfer programmes is the Harmonised Social Cash Transfer programme (HSCT), which came into being through the National Action Plan for Orphans and Vulnerable Children. Beneficiary households receive cash on a monthly basis and currently transfers are being made via Ecocash (a mobile money platform) and rates depend on household size. According to Dewbre, Prifti, Ruvalcaba, Daidone and Davis (2015), the HSCT programme is a livelihoods support strategy and, as such, it underscores the developmental function of social protection. The HSCT aims to boost the wellbeing of poor and vulnerable families living in the poorest households in Zimbabwe (Mtetwa & Muchacha, 2013).

The programme is intended to harmonise with and complement other social protection programmes, notably the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) and Assisted Medical Treatment Orders (AMTOs). In this way the HSCT can be developmental, because it can be used to stimulate children's education after they are enrolled in the BEAM programme and if they fall ill, they get free medical assistance through AMTOs. As such, children will be able to access education with enough food and proper healthcare and they will find it easy to make investments in human capital development. Moreover, for children, the HSCT programme reduces the chances of their becoming subjected to child labour and early pregnancy, and it assists them to focus productively on their education (Mtetwa & Muchacha, 2013), thus having a preventive function. However, the harmonisation of the programme with BEAM and AMTOs has been problematic as a result of various challenges.

The DSD also offers cash transfers for food-poverty mitigation (cash for cereals). The DSD is mandated to provide vulnerable households with food to fight hunger, with each household entitled to a 50 kg bag of grain per month - be it maize, millet or rapoko. This grain is still being given in rural areas if the need arises, and in urban areas the provision of grain has been substituted (not removed) with cash, with food-poor households now receiving transfers via One Money (a mobile money platform). This cash is basically meant for the purchase of foodstuff.

Transport assistance

The DSD assists vulnerable people with transport money through the 'warrant system' which applies to road and rail transport. Clients of the DSD who need to travel are given warrants at district offices and they use these warrants to travel. After that, the bus or train operator who would have ferried the client(s) will be paid by the government upon submission of a claim. The facility is for long-distance journeys only. A voucher or token system is also in place in selected rural districts and it is mainly intended for emergency cases. However, the programme is currently faced with numerous challenges and assistance has been minimal, if available at all in most instances, as private bus operators shun the warrant system.

Assistance to persons with disabilities

The DSD, at the sub-national level, processes applications for any form of assistance for persons with disabilities and submits them to the Department of Disability Affairs at its head office in Harare. This Department then procures assistive devices for persons with disabilities or pays vocational training fees, and payment is made by the government to a selected service provider or supplier. The DSD also processes income-generation projects' loan applications for persons with disabilities and submits them to the Disability Affairs Department at Head Office for payment. The loans are meant to financially empower persons with disabilities, but this is a revolving fund - the loans have to be paid back at 15% interest per year. In addition, the DSD also processes applications for people with disabilities pursuing tertiary and vocational training, and application forms are sent to the head office for payment.

DEVELOPMENTAL WELFARE SERVICES BY THE DSD: WHERE ARE WE AND WHERE DO WE INTEND TO GO?

As it stands, no official framework has been put in place by the DSD on how developmental social welfare will be implemented in Zimbabwe. However, there is a National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe (NSPPF) which was put in place in 2016 within the framework of the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation.5 Even though the economic blueprint was succeeded by the Transitional Stabilisation Program and the National Development Strategy 16, the NSPPF remains the basis for provision of some developmental social welfare services in Zimbabwe - a situation that needs to be rectified.

The NSPPF is predicated on three approaches to social protection; they relate to social protection as a human right, having a systems approach to social protection, and a multi-sectoral approach to social protection (MoPSLSW, 2016). These approaches are reflective of developmental social welfare as highlighted by Dutschke (2009), Ntjana (2014) and Midgley and Pawar (2017). According to the MoPSLSW (2016:27-28), the NSPPF recognises the five main pillars of social protection as: (i) social assistance, (ii) social insurance and (iii) labour market reforms, (iv) various programmes aimed at supporting livelihoods and resilience at various levels (individual, family, community and society as a whole), and (v) social support and care.

In line with these pillars, the goals of the NSPPF relate to: (i) supporting the poor in developing skills that would enable them to become employable and self-reliant, (ii) enhancement of equitable access to basic social services, (iii) improving the provision of social welfare assistance to the poor and vulnerable, (iv) enhancement of the protection of workers and their dependants against risks that threaten income insecurity, and (v) creation of conditions that promote equity and opportunity and build resilience, self-esteem and empowerment (MoPSLSW, 2016: 32).

The key elements of the NSPPF include access to basic services, social transfers, social support and care services, harmonisation and coordination, and capacity development (MoPSLSW, 2016). On access to basic services, the NSPPF consists of programmes that improve access to services for people at all levels and they are intended to help people realise their full potential. One of the cornerstones of the NSPPF is the integration of all social protection programmes in Zimbabwe towards creating a strong 'social protection system', and this system is supposed to be helpful in the eradication of the numerous vulnerabilities of all people. Despite such a strong policy element, the creation and implementation of a vibrant national 'social protection system' as championed by the NSPPF has yet to be realised. Having such a system will bring several government departments together towards improving the welfare of people - a key feature of a developmental welfare state (Dutschke, 2009). Moreover, the manner in which various government departments are to work together in creating one social protection system is not clear in the NSPPF - something that is very clear in South Africa's ISDM of 2011. In the event that future changes are to be made or a new framework is to be developed, the ISDM can be used as a yardstick for this integration.

Another element that is of importance is the provision of social cash transfers (MoPSLSW, 2016). The social transfers being given in line with the NSPPF are unconditional and are supposed to help food-poor households, particularly those in rural areas, avoid reliance on ad hoc coping mechanisms such as selling productive assets - something that helps them to continue being self-reliant. However, the current social transfer programme in Zimbabwe is not predictable, consistent and sustainable, and to make matters worse, there is no exit strategy in sight. The transfers are negligible given the current economic challenges in the country and at the end of the day the aims of the social transfer programme are not achievable as poverty continues to have a crushing impact on beneficiaries.

Another key element of the NSPPF relevant to this discussion is that of harmonisation and coordination. The NSPPF was designed towards harmonisation, integration and the institution of synergies between several strategies, systems and programmes within and outside the DSD and this has the potential to improve the efficacy of service delivery (MoPSLSW, 2016). A very good example of harmonisation and integration is that of the HSCT, the BEAM and the AMTOs. In line with the NSPPF, the harmonisation of these three programmes was supposed to be enhanced towards improving the coping capacities, the capabilities and the potential of food-poor households - as illuminated under cash transfers in the previous section. However, the harmonisation of these programmes has failed to translate into a beneficial reality. One reason for the lack of proper harmonisation might be the lack of clarity in the NSPPF on how these three programmes were supposed to be harmonised. Lessons will have to be drawn from South Africa's ISDM, as it clearly spells out how social welfare programmes and services are integrated into one towards enhancing the provision of developmental social welfare.

Moreover, there is supposed to be coordination in the provision of social welfare services among several government agencies and departments, as reflected in the South African ISDM (RSA, 2011). In Zimbabwe, cooperation is evident amongst government departments, but it needs to be reinforced by mandating other government departments to adopt developmental social welfare approaches in conducting their business so that the provision of such services becomes holistic. Lessons can be learned from the ISDM, where the government of South Africa gave a directive for all departments to put in place mechanisms that recognise social service professionals within their departments, develop referral systems to link vulnerable children with necessary resources, and commit resources towards the delivery of social welfare services that seek to promote child welfare in the various provinces of South Africa (RSA, 2011).

Despite the NSPPF having a developmental orientation, the developmental nature of the programmes and services of the DSD is debatable. An example relates to programmes and services related to child protection. In comparison with the ISDM of South Africa, when it comes to child offenders, one aspect that relates to developmental social welfare is the prevention and early detection of child committal. In Zimbabwe, prevention and early detection are not part of the conversation when it comes to child committal and, as such, the DSD's approach is curative, yet prevention has always been better than cure. According to the South African Department of Social Development (RSA, 2011), prevention and early detection are important components of the ISDM as they help in detecting causes of problems and dealing with those causes before the problems affect a large part of the population. This avoids costly intervention at a later stage (Dutschke, 2009; Kurevakwesu, 2017). In a way, the DSD has to identify - through research - the major problems that promote vulnerability in Zimbabwe, investigate their major causes and work on forestalling these causes by empowering and improving the resilience of communities. This will improve the capability, independence and self-sufficiency of people, and in the long run reduce the number of people in need of social welfare services.

The NSPPF also focuses on the enhancement of capacity development initiatives for the DSD so that all objectives of the NSPPF are achieved (MoPSLSW, 2016). There is no question that the institutional capacity development of the DSD has been weak over the years as a result of the poor remuneration of SDOs and probation officers throughout Zimbabwe - something that affects attempts to strengthen the administration of social protection programmes and the improvement of service delivery. Despite the poor remuneration of employees within the DSD, there are other challenges that militate against proper service delivery, and these include the employment of non-social workers in positions that are reserved for social workers (Kurevakwesu, Chikwaiwa & Mundau, 2022), and the shortage of human, financial and material resources. If the DSD is serious about the implementation of developmental social welfare services, SDOs have to be properly remunerated as they are at the heart of the implementation of such services. This has to be the first step towards the enhancement of the capacity of the DSD to work on achieving the objectives of the NSPPF or any other future frameworks.

Now that the DSD has made a bold statement of intent towards the creation of a developmental welfare state, there is need for a revised official framework on how developmental social welfare will be implemented. Even the consultants who prepared the NSPPF argued that the policy options provided in the framework were the ones considered to be critical at the time. They contended that - every now and then - there will be a need for revisions so that the framework is continuously adjusted to meet the socioeconomic conditions prevailing in Zimbabwe at any given point in time. With the need to formally implement developmental welfare services, it seems the time is now ripe for a thorough revision of the NSPPF or the promulgation of a new policy framework altogether. In developing the framework, there will be need to borrow features from South Africa's ISDM. Despite the ISDM (RSA, 2011) being promulgated in 2011, it has been the basis for South Africa's implementation of developmental social welfare, and as such, it can provide insights for any country that intends to undertake developmental projects.

What is known is that the DSD intends to ensure that people are capacitated instead of having to rely on handouts. Moreover, the DSD intends to provide livelihood support initiatives to vulnerable members of society and these will enhance income-earning opportunities, build the capacities of people towards developing self-reliance and resilience, offer services that support asset development or reconstruction of community assets, provide microfinance to enhance their productive capacity, and support efforts to reduce environmental degradation. As there is not much information available on how some of these initiatives will be rolled out, we offer the following recommendations for the DSD towards the creation of a functional developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE DSD

Below are some suggestions of what the DSD can do to expedite the creation of an efficacious developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe.

• First of all, there is need for an amendment to the Social Welfare Assistance Act (Chapter 17:06) of 1988 (GoZ, 1988) so that it becomes the basis for the provision of developmental welfare services. The Act is still focused on the provision of remedial welfare services and this can affect the effectiveness of any thrust towards the creation of a developmental welfare state. A reorientation of the Act will set the stage for a complete transformation of Zimbabwe's social welfare system and will set a precedent for the development of a strong policy or framework towards the provision of developmental welfare services.

• The DSD has to come up with a comprehensive framework for the provision of developmental social welfare services - where they have to lay out the services to be provided, levels of intervention, life stages and focus areas - just as the ISDM of South Africa does. The framework should explain how the current programmes being offered by the DSD are to be transformed or incorporated into developmental welfare programmes - something that is not clear in the NSPPF. It will be very difficult, if not impossible, for the DSD to fully commit to developmental social welfare services provision without such a framework because it will stand as a map to chart the social welfare terrain and inform SDOs within the DSD on how they can best implement the approach.

• It is one thing to have a sound framework and another for it to be properly implemented. As such, there is a strong need to make sure that if a new framework is developed, structures are also set in place to ensure its successful implementation. Zimbabwe has a record of having sound policies and yet the implementation of such policies has been poor. If the creation of a developmental welfare state is to be successful, any framework developed towards the provision of developmental welfare services has to be effectively implemented.

• The DSD has to work closely with the Council of Social Workers of Zimbabwe in improving professional social work regulation, particularly the training of social workers, social work education and the registration of social workers. For the creation of a developmental welfare state to be successful, there is a need for a competent workforce and this can only be possible if professional social work regulation is improved (Kurevakwesu et al., 2022; Lombard & Wairire, 2010).

• There will also be a need to ensure that SDOs have good working conditions and that they are well remunerated. It will be difficult for SDOs to work towards the development and welfare of people, if their own welfare is in question.

• The DSD has to make sure that all needed resources are drawn upon towards the creation and sustainability of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe. These resources should include human, material and financial resources. In line with Alpaslan and Schenck (2012), and Patel and Hochfeld (2008), it is difficult to implement developmental social welfare services without the necessary resources.

• Correspondingly, it is important to educate all SDOs on developmental social welfare and what it entails. Several studies have established that there is a lack of understanding among social workers themselves about what developmental social welfare entails (Lombard, 2007; Lombard, 2008; Ntjana, 2014). If this is the case in Zimbabwe, it will be difficult for SDOs to implement developmental social welfare policies. SDOs can be educated through seminars, meetings, workshops and manuals.

• It is also important to note that the most promising initiatives in Africa fail because of a lack of political will (Hölscher, 2008; Patel & Hochfeld, 2008). As such, there will be a need to ignite the enthusiasm of the political leadership for the creation of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe. This can be done by Directors within the DSD, through relevant channels into Parliament and even to the Head of State, because having a developmental welfare state will in the long run contribute towards the development of the country.

• Provision of developmental welfare services should be holistic and, as such, all government departments must adopt developmental welfare approaches in their business. In Zimbabwe such departments include the Zimbabwe Republic Police, the Zimbabwe Prisons and Correctional Services, the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, and the Ministry of Justice, among others. These departments also work towards promoting the welfare of vulnerable groups in society, particularly women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, among others. In line with the ISDM of South Africa, they should put in place mechanisms that recognise SDOs within their departments, develop referral systems to link vulnerable people with the necessary resources and to commit resources towards ensuring that any thrust towards improving the welfare of vulnerable people is developmental.

• Some of the most pressing social problems in Zimbabwe relate to poverty, unemployment and poor housing. As such, the DSD should make sure that whatever framework they design towards the provision of developmental social welfare services takes these social ills into consideration - and proffer sustainable ways of dealing with them by addressing their root causes.

CONCLUSION

This article explores the social welfare terrain in Zimbabwe and recent developments in the creation of a developmental welfare state. It is important to note that most of the programmes and services being implemented by the DSD are still remedial in their stance despite the presence of the NSPPF and the government's statement of intent in June 2020 towards a reorientation of the provision of social welfare services. Given this, we offered policy, practice and programmatic recommendations that can help in the creation of a developmental welfare state in Zimbabwe, with South Africa's ISDM being used as a yardstick. Just like the 'inside perspective' adopted in this article, all social workers in Zimbabwe can contribute towards the creation of a unique developmental welfare state, as this will reinvigorate the work of the DSD, improve child welfare services and overall service delivery, reduce the incidence of poverty and several other social ills, and consequently improve the recognition of the social work profession in Zimbabwe. Remarkably, Lombard and Viviers (2021) see developmental social work as the foundational paradigm for the next big leap of social work in this continuously evolving world. Embracing it at the current moment will help Zimbabwean social workers to be part of the international social work community and to easily adapt their response and interventions to the changing nature of social problems.

Notes

• Since the departments responsible for provision of social welfare services in both Zimbabwe and South Africa are all called by the same name - Department of Social Development - the one for South Africa is specified as the South Africa's Department of Social Development throughout the article.

• As there is not much literature on developmental social welfare from other African countries, the bulk of the literature that was reviewed in this article is on South Africa, where the government has successfully adopted a developmental welfare stance. This makes Zimbabwe the second country in Africa to formally adopt a developmental approach to social welfare.

REFERENCES

ALPASLAN, N. & SCHENCK, R. 2012. Challenges related to working conditions experienced by social workers practising in rural areas. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(4): 400-419. [ Links ]

CASSIM, A. 2016. What happens to policy when policy champions move on? The case of welfare in South Africa. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. [ Links ]

CHIWARA, P. & LOMBARD, A. 2017. The challenge to promote social and economic equality in Namibia through social work. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(4): 562-578. [ Links ]

DEWBRE, J., PRIFTI, E., RUVALCABA, A., DAIDONE, S. & DAVIS, B. 2015. Zimbabwe's Harmonised Cash Transfer Programme: 12-month impact report on productive activities and labour allocation. PtoP project report. Rome: FAO. [ Links ]

DLAMINI, C. N. 2020. Social protection and social development in Swaziland. In: TODD, S. & DROLET J. (eds.). Community practice and social development in social work. Singapore: Springer. [ Links ] DOMINELLI, L. 1997. Social work and social development: a partnership in social change. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 12(1): 29-38. [ Links ]

DUTSCHKE, M. 2009. Developmental social welfare policies and children's right to social services. PART TWO: Children and Social Services. South African Child Gauge 2007/2008. Cape Town: Children's Institute, UCT. [ Links ]

GIL, G. D. 1999. Developmental social welfare services: a solution for the challenges facing social welfare globally. New Global Development, 15(1): 1-7. [ Links ]

GoZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE) 2001. Private and Voluntary Organisations Act (Chapter 17:05). Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

GoZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE) 1988. Social Welfare Assistance Act (Chapter 17:06). Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

GoZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE) 1999. The National Orphan Care Policy. Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

GoZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE) 1991. Children's Act (Chapter 5:06). Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

GoZ (GOVERNMENT OF ZIMBABWE) 2008. Disabled Persons Act (Chapter 17:01). Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

HAMPSON, J. & KASEKE, E. 1987. Zimbabwe. In: DIXON, J. (ed.). Social welfare in Africa. London: Croom Helm. [ Links ]

HASSIM S. 2006. Gender equality and developmental social welfare in South Africa. In: RAZAVI, S. & HASSIM, S. (eds.). Gender and social policy in a global context: social policy in a development context. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

HÖLSCHER, D. 2008. The emperor's new clothes: South Africa's attempted transition to developmental social welfare and social work. International Journal of Social Welfare, 17(2): 114-123. [ Links ]

KALINGANIRE, C. & RUTIKANGA C. 2014. The status of social work education and practice in Rwanda. In: SPITZER, H., TWIKIRIZE, J. M. & WAIRIRE G. G. (eds.). Professional social work in East Africa: towards social development, poverty reduction and gender equality. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers. [ Links ]

KASEKE, E. 1998. Zimbabwe. In: DIXON, J. & MACAROV, D. (eds.). Poverty: a persistent global reality. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

KASEKE, E. 2001. Social development as a model of social work practice: the experience of Zimbabwe. SSW Staff Papers, Harare: School of Social Work. [ Links ]

KUREVAKWESU, W. 2017. The social work profession in Zimbabwe: a critical approach on the position of social work on Zimbabwe's development. Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(1):1-12. [ Links ]

KUREVAKWESU, W., CHIKWAIWA, B. K. & MUNDAU, M. 2022. The struggle for social work professional identity in contemporary Zimbabwe: a study on abuse of the social work title. Qualitative Social Work, 0(0): 1-17. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. 2007. The impact of social welfare policies on social development in South Africa: an NGO perspective. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 43(4): 295-316. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. 2008. The implementation of the White Paper for Social Welfare: a ten-year review. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 20(2): 154-173. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. 2019. Developmental social work in South Africa. In: VAN BREDA, A. & SEKUDU, J. (eds.). Theories for decolonial social work practice in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. & VIVIERS, A. 2021. Rethinking social work's role in a rapidly changing world. [Online] Available: https://researchfeatures.com/rethinking-social-works-role-rapidly-changing-world/ [Accessed: 17/02/2022]. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. & WAIRIRE, G. G. 2010. Developmental social work in South Africa and Kenya: some lessons for Africa. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, Special issue April: 98-111. [ Links ]

MANYAMA, W. 2018. Where is developmental social work as social work practice method in Tanzania? The case of Dar es Salaam region. International Journal of Social Work, 5(2): 43-57. [ Links ]

MHIRIBIDI, S. T. W. 2010. Promoting the developmental social welfare approach in Zimbabwe: challenges and prospects. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 25(2): 121-146. [ Links ]

MIDGLEY, J. 1995. Social development: the development perspective in social welfare. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

MIDGLEY, J. & PAWAR, M. 2017. Social development forging ahead. In: MIDGLEY, J. & PAWAR, M. (eds.). Future directions in social development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

MoPSLSW (THE MINISTRY OF PUBLIC SERVICE, LABOUR AND SOCIAL WELFARE). 2016. National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe. Harare: Government Printers. [ Links ]

MTETWA, E. & MUCHACHA, M. 2013. Towards a national social protection policy: knowledge and lessons learned from a comparative analysis of the design and implementation of public assistance and Harmonised Social Cash Transfer programmes in Zimbabwe. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 11(3): 18-24. [ Links ]

MUPEDZISWA, R. 1988. Social work practice in Zimbabwe and the factors instrumental in its development. Paper presented during an Exchange Visit to the University of Zambia. Lusaka, Zambia. June 6, 1988. [ Links ]

MUPEDZISWA, R. 2001. The quest for relevance: towards a conceptual model of developmental social work education and training in Africa. International Social Work, 44(3): 285-300. [ Links ]

NTJANA, N. J. E. 2014. The progress of developmental social welfare: a case study in the Vhembe district, Limpopo. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. Masters' Thesis. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2016. Social Welfare and Social Development. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. & HOCHFELD, T. 2008. Indicators, barriers and strategies to accelerate the pace of change to developmental welfare in South Africa. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 20(2): 192-211. [ Links ]

PATEL, L., TRIEGAARDT, J. & NOYOO, N. 2005. Developmental Social Welfare Services. In: PATEL, L. (ed.). Social Welfare & Social Development in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa [ Links ]

RSA (REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA). 2011. The Department of Social Development Framework for developmental social welfare services. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SPITZER, H. 2019. Social work in East Africa: a mzungu perspective. International Social Work, 62(2): 567-580. [ Links ]

TWIKIRIZE, J. M., SPITZER, H., WAIRIRE, G. G., MABEYO, Z. M. & RUTIKANGA, C. 2014. Professional social work in East Africa: empirical evidence. In: SPITZER, H., TWIKIRIZE, J. M., & WAIRIRE, G. G. (eds.). Professional social work in East Africa: towards social development, poverty reduction and gender equality. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain. [ Links ]

WAIRIRE, G. G. & KIBORO, C. N. 2014. Social work perspectives in poverty reduction and social development in Kenya. In: SPITZER, H., TWIKIRIZE, J. M. & WAIRIRE G. G. (eds.). Professional social work in East Africa: towards social development, poverty reduction and gender equality. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers. [ Links ]

1 The Department of Social Services and the Department of Child Welfare and Probation Services were two different departments that came out of the Department of Social Welfare and were both under the same Ministry, i.e. the Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare.

2 The East African Community is an intergovernmental body of 6 countries that are in the Great African Lakes region in Eastern Africa. These countries are Uganda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi.

3 Social Development Officers (SDOs) are qualified social workers employed within the DSD and they were formerly known as Social Welfare Officers. However, due to the poor regulation of professional social work in Zimbabwe, and the massive emigration of social workers to the UK, Australia, Canada, the USA and several other countries, graduates in Sociology, Psychology and Development Studies are also employed as SDOs within the DSD.

4 ZWL stands for the Zimbabwean Dollar which is facing high levels of inflation. As such, most people - upon getting their salaries and grants - usually buy United States Dollars (USD) on the parallel market.

5 The Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation was Zimbabwe's economic blueprint from 2013 to 2018. It was enacted by the government of Zimbabwe to direct socio-economic development. The economic blueprint was succeeded by the Transitional Stabilisation Program which was adopted from 2018 to 2020, and the National Development Strategy 1 succeeds the Transitional Stabilisation Program.

6 The National Development Strategy 1 is Zimbabwe's current economic blueprint and it covers the years 2021 to 2025. National Development Strategy 1 precedes National Development Strategy 2 which will be adopted from 2026 to 2030. The two strategies are in line with the government of Zimbabwe's Vision 2030 which charts a new transformative and inclusive development agenda, while instantaneously addressing the global aspirations of the Sustainable Development Goals and Africa Agenda 2063.