Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.57 n.4 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-968_903

ARTICLES

The use and value of a child assessment tool (CAT) in social work child assessments

Thenjiwe MlotshwaI; Dr Maud MthembuII

IPostgraduate student, Department of Social Work, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. mlotshwaandiswa@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of KwaZulu-Natal. Durban, South Africa. mthembum4@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The integration of child-friendly tools during child counselling facilitates effective communication and child participation. However, the use of child-friendly tools in generalist child counselling remains sparse. This paper presents social work students' perceptions of using a child assessment tool (CAT). While the study adopted a mixed-method approach, this paper reports the findings drawn from the study's qualitative findings. Data collection included individual semi-structured interviews with purposively sampled fourth-level student social workers. The results indicated that using the CAT created a child-friendly environment that facilitated effective child communication and participation during assessments. Using the CAT addresses barriers to child participation during child assessment.

Key words: child assessment tool (CAT), child-centred, child friendly, communication, participation, social workers

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Assessment in social work plays a vital role in intervention planning. In South Africa the high prevalence of adverse childhood experiences and abuse places a child's emotional wellbeing at risk. Early identification of psycho-social challenges through assessment is a critical starting point for social work. Timely and appropriate assessment initiates the starting point for ascertaining whether the child is in need of care and protection (Children's Act 38 of 2005, section 155), and the application of suitable intervention afterwards (Spies, Delport, & le Roux, 2017).

Adults have predominantly been the main narrators or voices of children in child assessments. Studies that investigated professionals' decision to place adults at the forefront of matters affecting children found that children were often regarded as minor characters, while parents were sought to give accounts on behalf of children (Munro, 2001; Holland, 2001). When children were discussed, it was often in relation to their parents or guardians, not as independent individual beings with their own personalities and stories to tell. As a result, child assessments have been adult-led to the extent where a child's view and concerns regarding matters that affect them have been negated or not given sufficient consideration. Similarly, in the health-care setting children were viewed as incapable of clearly communicating their health-related issues and needs; this perception of children has been used to justify the lack of children's involvement in matters affecting them (Mutambo, Shumba & Hlongwana, 2019). Consequently, the effectiveness of an intervention becomes unfit for a child who was not consulted nor involved during assessment. Ferguson (2017) and Husby, Slettebo and Juul (2018) investigated children's participation in child protection from the perspectives of professionals and children themselves. Their findings indicated that professionals who aimed to establish intimate and trusting engagements with children through active listening, play, touch and close observation obtained authentic entries into the children's world. Hence, this increased children's responsiveness and active engagement in the helping process.

Internationally, children's rights - specifically active child participation - have received optimistic attention, and recommendations have been made to strengthen the voices and the views of children on matters that concern them (Ruiz-Casares, Collins, Tisdall & Grover, 2017). In social work assessment, the literature on child-friendly assessment tools that facilitate children's engagement during counselling is scarce. While there are tools available that map out children's risks, their limitation is that they do not encourage the child's autonomy to decide what to disclose in a session. Furthermore, most tools are administered by a social worker (Franklin, Brown & Brady, 2018; Vial, Assink, Stams & van der Put, 2020; National Department of Social Development & UNICEF, 2012), which allows a child a minimal role in determining what they prefer to talk about.

The lack of participatory and child-friendly assessment tools that can be used by child-care workers and social workers working with children was one of the factors influencing the development of the Child Assessment Tool (CAT) (Zoë Life Innovative Solutions, 2018). CAT is a screening tool developed by Zoë Life Innovative Solutions and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Social Work Department, as a response to the lack of viable tools to use in the early identification of childhood maltreatment. Given that many children in South Africa are exposed to adverse childhood experiences such as abuse, violence and poverty, children may not have adequately developed verbal articulation skills to express their experiences fully. To mitigate children's exposure to adverse childhood experiences and to ensure that healing takes place, practitioners need to use child assessment tools that provide safe entry points into the child's world, while simultaneously eliciting valuable information. Hence, the development and utilization of the CAT by student social workers working with children became a crucial point for establishing a better understanding of the significance of using the CAT during counselling interactions with children.

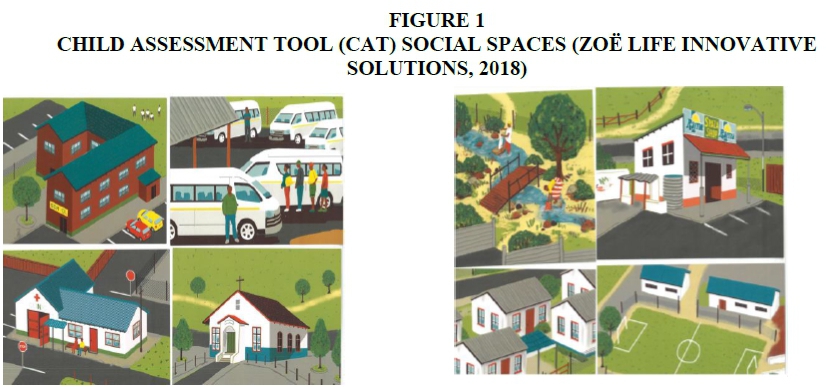

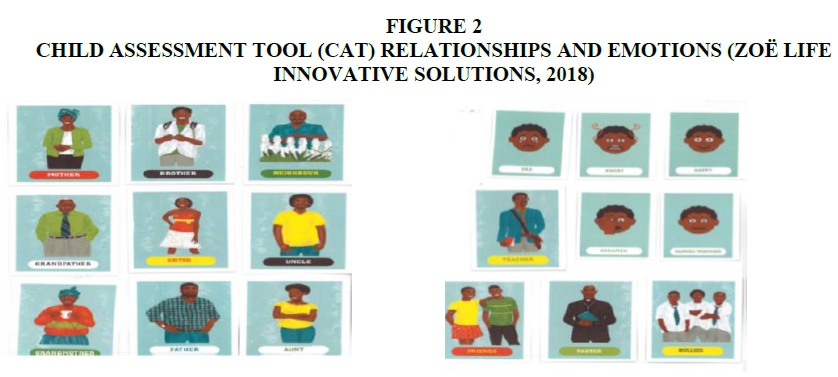

The CAT is a context-appropriate screening tool made up of several pictorial cards that depict a child's social spaces, relationships and emotions. The social worker gives the child the tool in order for the child to narrate their own life story through it. It is useful for conducting a holistic assessment of the child's life, while placing the child at the forefront of the process. The first stack of cards depicts social spaces that resemble the child's environment. For example, the tool has rural and urban environments. This includes the home, school, church, taxi rank. These are places or environments where a child may face the risk of abuse and neglect. The different people with whom the child may or may not have a relationship make up the second stack of cards. This also involves people that may subject the child to maltreatment, such as family members, friends, strangers and school staff. Lastly, the emotion cards portray the different emotions that the child may feel towards the different social spaces and people present or not present in the child's life (Zoë Life Innovative Solutions, 2018).

While a formal evaluation of the use of the CAT by social workers with children has not been formally conducted, earlier findings from the study conducted with community health-care workers demonstrated multiple benefits associated with using the CAT with children. The study indicated that the graphics of the tool enabled a child-led approach, which decreased children's anxiety and fear in the session, thus improving the quality of child assessment. Community health-care workers became more confident when using the tool as it aided their communication with children (Zoë Life Innovative Solutions, 2018). The above findings further motivated the piloting the CAT with other professionals working with children. Hence, the CAT was piloted with UKZN student social workers in their 4th year of study because of the potential of the CAT to promote and enhance child-friendly and participatory counselling spaces. Thus, the purpose of the study was to obtain student social workers' perspectives on the use and value of the CAT during encounters with children in counselling.

A literature review on assessment tools and the creation of child-friendly spaces will be presented to locate and contextualise the significance of the study. Thereafter, the ecological systems theory is discussed as the theoretical framework informing the study and the CAT. A brief discussion on the methodology then follows, which outline the research steps that were followed, leading to the findings drawn from the study. The paper will conclude by highlighting the main findings of the study and its limitations, and make recommendations for practice, research and education.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Assessment tools in social work

In social work there are various tools of assessment that are utilised for a range of purposes and in different phases of the social work process. One of the main reasons for using assessment tools is that they assist the professional to examine the various aspects of the client's life (Parker, 2017). The most commonly used assessment tools are ecomaps, genograms and sociograms. The purpose of using assessment tools in social work is to guide social workers towards a comprehensive understanding of the client and the presenting situation. Often social workers would use the above-mentioned tools to graphically present the information obtained from clients. Literature on client-centred assessment tools focusing on fostering disclosure of information is rare.

In the South African social welfare context, there are no standard safety and risk-assessment tools used by professionals. As a result, this leads to inconsistencies in assessments, negatively affecting service delivery to children at risk (Spies et al., 2017). Yet not having standard safety and risk-assessment tools does not imply that assessment tools are non-existent or not utilised in social welfare. A study comparing different child-assessment tools was conducted by Vial et al. (2020). The National Department of Social Development and UNICEF developed an assessment tool for children in alternative care. The tool requires the involvement of a multidisciplinary team in ensuring that holistic information is obtained about the child, such as the social interactions and relationships as well as the different environments that influence the child's development (National Department of Social Development & UNICEF, 2012). It is valuable in assessing children's wellbeing and in developing their individual development plan (IDP). Shiller and Strydom (2018) conducted research on a family assessment tool with social workers in Eastern Cape and Western Cape. The tool assists in identifying and prioritising family needs and services, and assessing family wellbeing. Although the social worker administers the tool, some level of participation is required from clients and service providers. The literature shows that there are valuable assessment tools for children and families that social workers can use. These assessment tools make a meaningful contribution to the counselling process and help to determine the most suitable intervention for a client. However, a common feature of these instruments is that they are administered by professionals whose orientation does not always allow the child the autonomy to share, give an account of, or reflect on their own lives in a way that suits them. This suggests a need for a change of approach in the development and administration of tools by professionals. In other words, tools that give children a voice in the helping process are still needed.

Facilitating a non-threatening child-assessment and child-friendly environment

According to Parker (2017), the social worker has an obligation to use age-appropriate techniques and tools to support the child, make them feel comfortable in sharing their story. The use of child-friendly assessment tools enables the child to be at the forefront in the helping process by shaping and influencing the intervention. In the African context, respect for adults and those in authority is one of the values taught to children, which often means that children are seen but not heard. In counselling, social workers must reduce this child-adult power imbalance by creating a safe space for children to communicate their opinions (Parker, 2017). This creates a child-friendly space and the assessment tools are therefore useful to facilitate this process. In this regard, the child assessment tool (CAT) that social work students used is child-initiated, meaning the child decides the story they want to share or what to share.

Considering that children are important knowledge givers and receivers, hearing about their experiences is valuable (Pölkki, Vornanen, Pursiainen & Riikonen, 2012). However, for a child to share, they need to be in a setting that is comfortable for them. Adopting and creating child-friendly assessments ensures that a child feels at ease to communicate with the social worker. This entails taking into account the child's age and using suitable play materials. Koprowska (2014) suggests that because children are not fond of sitting down and talking with an unfamiliar adult, social workers should be acquainted with using age-appropriate toys and creative activities that are most likely to result in successful engagements with children. Engaging children through playful and creative techniques enables the practitioner to enter the child's world and access it in a way that is comfortable and does not feel not interrogatory for the child (O'Reilly & Dolan, 2016). Furthermore, Reyneke (2013) and Marais and van der Merwe (2016) have advocated for the creation of child-friendly spaces that provide non-threatening choices during counselling and spaces that empower the child to regain a sense of control in matters affecting them. Hence, the integration of child-assessment tools during interactions with children becomes valuable in ensuring that a child-centred and participatory therapeutic setting is created.

Social workers conducting assessments with children cannot only depend on verbal assessments, but must adopt child-friendly and appropriate ways to conduct assessments. Creative tools allow social work practitioners to find a smooth entry point to work with clients of various ages and at different stages of the helping process. O'Reilly and Dolan (2016) reported on the benefits of using age-appropriate communication strategies with children during assessments. The recognition of play as a universal language for a child has encouraged the utilisation of play techniques in direct work with children. Adopting play strategies or tools enables the child to experience a child-friendly and suitable counselling environment that is focused on allowing the child to communicate in a manner that is befitting for the child. In addition, expression is not only evident in verbal cues, but the child displays facial expressions as he/she physically interacts with tools or play activities. These non-verbal cues can demonstrate a holistic understanding of the child's feelings, thoughts and views about the story being narrated (Kekae-Moletsane, 2008; Mutambo et al., 2019). This means that a child can benefit from and participate in the intervention process, provided that their language of communication, which is play, is incorporated into and accessible in the session (O'Reilly & Dolan, 2016).

The literature has substantially documented the usefulness of play therapy in facilitating safe counselling spaces for children (Brady, 2015), highlighting its helpfulness in assisting children to express their feelings and concerns in a child-centred way (Mutambo et al., 2019). Recently, there has been greater emphasis on the promotion of the indigenisation of social work practice through the integration of indigenous games and knowledge into counselling (Mkhize & Mthembu, 2019; Malobola-Ndlovu, 2018; Okpalaenwe, 2017). These attempts to enhance social work practice, specifically child assessments, are vitally important. It has been ascertained that some of the play-related activities incorporated into child counselling can improve child-social worker rapport and communication. Furthermore, it is held that a child is most likely to participate in a game that resonates with him/her.

Additionally, indigenous games such as Umcociso often encourage a child's self-determination and participation, in this way enhancing a child's ability to communicate their feelings related to an experience and explore options to resolve a problem. The social worker is then able to obtain valuable information about the child, the situation and the child's feelings. Handley and Doyle (2014) explored the views of social workers on their skills and competencies when eliciting the views of children. They found that social workers felt that they possessed some useful skills; however, their ability to engage in creative and play techniques and knowledge of the development stages of children enhanced their work. A lack of adequate knowledge of innovative, diverse or indigenous tools and strategies to improve communication with children is a barrier to effective child counselling (Husby et al., 2018). Therefore, studies seeking to explore the use and value of child-friendly communication tools for children are imperative in enhancing knowledge on providing child-centred counselling spaces.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Holistic assessments that seek to comprehend the different interacting spheres in an individual's life are imperative in social work. Therefore, the theoretical framework chosen had to reflect the nature of social work assessments; hence, the ecological systems theory informed the study. The basic premise of the theory is understanding that an individual coexists with the environment and thus to understand an individual, one has to understand the environment as well. Unique to the theory are the four interacting systems developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979): the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. To intervene in the child's life, the social worker has to understand the nature of the different systems and how they interact interdependently with each other. affecting the child's wellbeing (Ryan, 2001). When a child experiences distress, it indicates an imbalance or poor functioning in one of the systems in the child's life. When one or more systems are not contributing positively towards the development of the child, this will automatically have a negative impact on the other systems, especially the microsystem. This is because a reciprocal relationship characterises the systems (Walter, 2007).

The CAT consists of pictorial cards depicting places and people that children regularly interact with and influence the child's emotions, behaviour and daily experiences. The CAT also includes emotions cards to assess a child's perceived feelings. These are important elements that need to be explored during the assessment for it to be holistic. The social spaces and people presented on the tool enable the practitioner to assess the influence of the different sub-systems of the ecological theory, namely the micro-, meso-, exo- and macrosystems. The microsystem, which is the immediate environment of the child's life, consists of the closest relationships such as family, friends and teachers. The mesosystem is the bidirectional interactions that the different microsystems have with each other. For example, a nurturing and supporting interaction between the child's parents and teachers, the two microsystems, can positively influence the child's academic performance. The exosystem, the third area of analysis, may not influence the child's wellbeing directly; however, it impacts on the child's microsystem, and a change in these social interactions has an impact on the child (Ryan, 2001). Lastly, the macrosystem is represented by the church pictorial card, and it represents the environment that is the foundation of the child's belief and values which guide the child's behaviour and outlook on life. The child is central in the assessment process because they have to recount the narratives about present or non-present relationships, living conditions, emotions and general information that is crucial for identifying risk and developing informed interventions (Ryan, 2001). In this regard, the social worker can enter the child's world through the use of CAT, guided by the ecological systems theory. And the tool enables the social worker to understand the child in his/her context and from their perspective.

Furthermore, the children's rights approach highlights the importance of children's participation in assessment whereby the child is central and active in this process. International legislation such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (United Nations, 1989) articles 12 and 13 stipulate the participation rights of children and obligating states to fully realise this right in a manner that is most suitable for the child. Social workers working with children are mandated as per this legal framework and the Children's Act 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2005) to promote child participation through creating child-friendly and safe environments for children to communicate and participate freely in matters affecting them. An awareness that children are fond of play and colours, and are energetic, is the basic knowledge about children that can be used to enable child-friendly participation. CAT is a child-friendly tool that has incorporated colour, pictures and play into creating a participatory and fun assessment process.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Ethical clearance to conduct the study was granted by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSS/2184/018M), which permitted a mixed-method study to be conducted with social work students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. The purpose of the study was to explore the student social workers' perceptions of the impact of the CAT with children. This paper will discuss the qualitative aspect of the study.

Through adopting an exploratory research design, the study aimed to explore the views of student social workers on their use and perceived value of the CAT when working with children. The eight participants of the study were purposively sampled from a population of fourth-year student social workers who were required to use the CAT during their field practice. The student social workers were trained on CAT and practised using CAT with each other during tutorials before integrating the tool in field practice.

Information about the study and the ethical issues associated with participating in a study was presented to the student social workers before handing out the study information sheets and informed consent forms. The student social workers who volunteered to participate in the study signed and returned the consent forms; this took place before data collection. Eight student social workers were selected based on their eligibility to provide relevant information suitable to meet the study's aim (Sarantakos, 2005). The participants had to have used the tool with a minimum of five children.

The researcher individually met with the participants at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus, at a time and day that each participant had stated was suitable for them. Data were collected using individual semi-structured interviews, which allowed the participants to share their views and experiences on the CAT through answering open-ended questions (Whiting, 2008). The use of an interview schedule ensured that the researcher covered the key points needed for the study in sufficient detail.

To analyse the data obtained from the semi-structured individual interviews, thematic content analysis as described in Blanche and Durrheim (2006) was used. The analysis was comprised of five steps. It began with the researcher becoming familiar with the data through verbatim transcriptions of the eight audio recorded interviews and reading through them repeatedly. Immersion into the data was important. During this process, the identification of recurring responses (inducing themes) from the extracts was noted as well as the underlying insights emerging from the extracts (coding). The coded extracts were then aligned with the developed themes and there was further immersion in the extracts and themes in order to explore the arguments and meanings that emerged (elaboration). Finally, the aligned extracts were repeatedly read in conjunction with the themes to ensure that they were a faithful representation of the themes. The extracts that were not aligned to any theme were read again to ascertain whether they could be aligned to an existing theme, or whether a new theme should be induced.

The participation and contribution of research participants in a study is very valuable, so it is imperative that participants experience no harm during the research study (Wassenaar, 2006). The student social workers who were the participants in the study were respected and could exercise their autonomy by voluntarily participating or withdrawing from the study, as was stipulated in the informed consent letter. Respect and autonomy were ensured by providing the participants with information about the study before asking for their participation. Thereafter informed consent letters and forms were given to the students to provide them with information about the study (Strydom, 2005). Furthermore, to respect participants' privacy, their identities were concealed by not using their real names in the transcriptions and in this paper. Instead, each participant was given a pseudonym. Lastly, the signed consent letters and transcripts were stored in a secure and private place.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The following discussion of findings is based on the qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews. Two main themes are presented in the discussion, which focuses on the perceptions of the student social workers on the impact of using the Child Assessment Tool (CAT) with children.

The perspectives of student social workers on the impact of CAT in sessions with children

Observed children' responses during the counselling sessions using the CAT

A practitioner cannot elicit information from a child as from an adult; the child may respond with silence or with one-word answers such as 'yes' or 'no'. Koprowska (2014) asserts that engagement with a child will most likely be successful if the social worker makes use of age-appropriate toys and creative activities. Therefore, it is essential to use play materials that the child will be able to identify with and respond to. The extracts below are student social workers' views on their observation of children's response to CAT:

I would see them change whenever I would give them the tool kit, they would think we were going to play a game of some sort. (Nosi)

The minute you say 'I have picture ' it's exciting for them. Through that excitement it actually makes them willing to talk to the social worker. (Nomz)

Like I said, children like colour and playing, so by using the tool children shared information about themselves which was a way that encouraged them to participate. (Thuli)

The narratives show that the CAT allowed the child to feel excited and comfortable during the session. This echoed the needs of children, specifically their interest in play. When children are provided with non-threatening choices during counselling, it encourages them to regain their sense of control (Marais & Van der Merwe, 2016). The tool attracted the eyes of the child; the reaction to seeing the tool as narrated by Nosi was positive, because the child could relate it to a play-based activity. Studies on play therapy have reported positive benefits associated with using play-based techniques to help children have positive experiences in counselling (Mutambo et al., 2019).

Promotion of self-determination in participation

Article 13 of the UNCRC (United Nations, 1989) recognises that children are capable of forming and sharing views about matters concerning them, provided that a child-friendly environment and appropriate platform have been set up. Through using appropriate skills and techniques, children can voice their opinions in a way that is best suited for them. However, it is important to acknowledge that a child may decide to withhold information and not share personal information. All the participants shared positive accounts of how the tool encouraged the child to be involved in the session. The following are some of the points that were shared:

It gives the child space to speak freely and to choose in terms of leading which direction they want the interview or assessment to go. (Pho)

I would ask them what they think is happening in the picture and they would interpret in their own way. (Thobi)

It allows them to tell their own story in a way that they remember it through the picture that is being displayed. (Thuli)

It does make the child open up and talk, share information through looking at pictures and talking... When I took out the tool that they had begun to feel at ease and free and began to respond to me. (Sli)

These comments reveal the different ways the tool enabled children to be at the forefront of the counselling session, giving them autonomy to lead. Self-determination is an essential value in social, work because when the client is self-determined, he/she is empowered to be autonomous and self-reliant when it comes to committing to the actual intervention (Reyneke, 2010). Mabu explained how self-determination was achieved when using the CAT with the child:

It allowed the client to start where the client wanted to start. They would choose the picture, so it allowed me to start where the client wanted to start to allow the client to be self-dependent as well as self-determined in terms of what they want to discuss with the social worker. (Mabu)

Since the assessment tool allowed for physical interaction, children could pick up the pictorial cards that they wanted to speak about first and had the discretion to align them with any other card of their choice. This gave children the freedom to express themselves fully and comfortably about what they wanted to share. In addition to the self-determination, participants further shared that when children were able to participate using the CAT, it was exciting for them because CAT, in their view, was a form of play activity.

The child gets excited especially when they have to decide for themselves what to talk about and when I didn't use the tool, they would ask me if in the next session will I give them the tool. (Sli)

Safe environment for communication and expression

Most of the participants shared positive narratives about the physical appearance of the CAT; highlighting its play-nature form and colourfulness. These are the features that the participants noted as creating a child-friendly communication space. A child-friendly space, according to Metzler, Atrooshi, Khudeda, Ali and Ager (2014, cited in Mutambo et al., 2019) is a protective environment for children that allows them to learn, express themselves, build self-esteem and socialise in the way most suitable for them. Below are some of the narratives that focused on the features of the tool in facilitating a child-friendly communication and expression:

It is made for children because children like pictures and cartoons and it makes things easier for the child if they see something that is like for playing. (Aneli)

Like I said, children like colour and playing so by using the tool children shared information about themselves which was a way that encouraged them to participate. (Thuli)

Van Nijnatten and Van Doorn (2013), who researched children's participation in psychotherapy, support the above views by asserting that playful activities decrease the formality of the therapeutic communication in which children may feel out of place. In this regard, CAT became the means by which children were actively involved and felt comfortable in the session, thereby enhancing their confidence to participate. For instance, children became encouraged to discuss features of their lives they preferred to discuss:

It allows the child to be at ease within the session. To feel like they are in a safe environment to disclose things that they would not be able to disclose to the teacher or to the parents. (Nomz)

They made it easier for them to participate - that's how I saw it. It did not make them feel like they were being interrogated. It made them like they were talking to a friend and I think it made them feel aware that you are there as a friend. (Mabu)

The observations by the participants reveal that children's participation is affected by the type of counselling environment that a social worker creates. When the counselling space does not resonate or make the child feel comfortable, this can be reflected in the child's non-verbal behaviour. This assertion can be related to the bi-directional relationship of systems in the ecological systems theory. In this regard, the social worker and the counselling space are at a meso-level; therefore to encourage effective engagement with the child, this system has to be adapted to suit the needs of the child. When there is a balanced relationship, it means that the child and social worker will both benefit from the counselling session. Koproskwa (2014) acknowledges that children are not fond of sitting down and talking to an adult whom they do not know. The use of child-friendly tools is encouraged because of their potential for reducing tension in the counselling session between the child and social worker (Koprowska, 2014)

Experiences of student social workers on using the CAT

Enhanced understanding of working with children

The utilization of the CAT with children did not only benefit children, as noted by the participants; however, it also enhanced the participants' knowledge about children. As children engaged with the CAT, participants observed children's verbal and non-verbal responses. As a result, they gained a better understanding of children. This interdependence can be associated with the bi-directional influence of systems in the ecological systems theory. One participant commented:

It taught me that children can display their experiences in other ways than talking, through looking at photos and express themselves through facial expressions. (Mabu)

The body you can observe through them viewing the picture on what type of attitude they have towards that person. It does not only allow them to speak verbally but it allows them to also disclose body language towards the social worker so it gives a lot of information. (Nomz)

Observing the child while engaging with CAT proved to be insightful for the participants. Through observation the participants gained more information about that particular child but also children in general. The participants were further able to compare and reflect on the accounts as they engaged with different children. Nomz was able to identify similarities amongst the children she engaged with using the CAT.

I observed that children want to focus on positive things like areas where they are doing well and their favourite things. (Nomz)

The participants were able to identify areas of concern in the child's life based on the child's response to a particular pictorial card or emotion card. Hence, most of the participants established that the home environment was a social space which child seemed not to want to talk about, thus signifying that potential risk or discomfort emanates from home.

So that really enhanced my knowledge in terms of that home is not always the best place that the child wants to speak about. (Pho)

They did not like talking about what is happening in their home; they would talk briefly about the home and move on quickly to the next picture. (Aneli)

The tool made me realise that children know a lot about what is happening in the family but they don't like talking about it. (Sli)

Obtaining valuable insight into the child's perception of the home challenged most of the participants preconceived ideas about how children would feel about the home. Some participants assumed that home would be the child's favourite place to speak about because home is regarded as a place of safety, love and care. However, for some of the children whom the participants engaged with, this proved to be not the case. Pho admitted having assumed that the home would be a child's first point of reference:

So most of the time we have our own perception of what the child would want to talk about, the home. (Pho)

Participants also noted that when the home seemed to be an uncomfortable environment for the child, the school became a social space in which to get know the child as children, and they would actually enjoy talking about the school first. All the participants' comments suggested through CAT that children wanted to talk more about school.

The school was one of the major places that kids liked. The school allowed us to understand who the child is. For some, school was a place for them to escape problems they were facing. (Mabu)

It is evident from the comments of the participants that the CAT was valuable in providing insight into the children's social spaces; this challenged incorrect assumptions by the participants about children and allowed them to learn more about children through the pictorial cards. Furthermore, the comments exemplify the premise of the ecological systems theory, which emphasises the understanding of an individual in relation to his/her environment. Moreover, it allowed the participants to witness a transformation in the child when talking about the home and school environment; this indicates the influence and role that the different environments have on the wellbeing of the child.

Benefits for student social workers' practice

In addition to gaining a better understanding of children through using the CAT, the participants noted the benefits associated with using the tool during practice. One of the key insights gained was the value of involving children and allowing children to be in the forefront of assessment. Below are the insights of the participants:

The tool has enhanced my understanding in terms of always beginning where the client wants to begin. So most of the time we have our own perceptions of what the child would want to talk about home. (Pho)

It is important because if you cannot gather information from the child who will you gather information from? So I can say it was effective in terms of helping me gather information from the child. (Nosi)

It allows the social worker to gain a lot of information through interacting; there is so much that you are learning about the client. (Mabu)

Mabu further noted that if she had not used the CAT, she would have struggled to get the child to engage interactively. It is valuable when practitioners can reflect on their practice and elicit knowledge about children when using the CAT with children and acknowledge areas needing improvement - specifically, when the participants are able to identify their own role in facilitating a constructive and child-friendly counselling space with children. The extracts that follow reveal that as they gained information about children through observation and listening, they responded appropriately to the child:

When it came to talking about that specific problem or that specific person who was doing something to that child, that's when you realise that this where I need to focus on because they would draw back from talking about this person or problem. (Thuli)

There is a way of nurturing them to actually engage with you and the toolkit is one of the ways that allows the social worker to engage with the client. (Mabu)

The insight shared by Mabu is supported by Van Velsor (2004) that children do not intentionally avoid the verbal expression of feelings but children often need a practitioner to create a space in which they can engage and express themselves.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

The paper presented the findings of the use and value of the child assessment tool (CAT), a screening tool that was used by student social workers during counselling sessions with children. The perceptions shared by the participants revealed that using the CAT benefitted the child in terms of facilitating a child-friendly counselling space that enabled the child to participate freely and feel autonomous in the session. In turn, the student social workers gained a better understanding of the child who, through verbal and non-verbal expressions, communicated valuable information about their lives and especially about their social spaces. It also gave the participants an opportunity to reflect on their own practice and knowledge about children, which transformed their taken-for-granted assumptions about children.

Despite the value of the CAT as described by the participants, research with the children who had used the CAT could have potentially provided more insightful accounts of the use and value of CAT. Furthermore, while the tool was context-specific, it did not necessarily mean it could be utilized with all children. For example, children who may be visually or hearing impaired, or children who reside in alternative care such as in child and youth care centres, may not benefit fully from using this tool.

Nevertheless, the findings of the study are sufficient to recommend that the CAT be introduced in the different training institutions responsible for the education and training of human service professionals such as social workers, social auxiliary workers, and child and youth care workers. Integrating the CAT into their practice can give student human service professionals early exposure to child-centred and child-friendly tools of communication and assessment. Further research into ways CAT can be adapted for children with different development capabilities and those from alternative care is recommended.

REFERENCES

BLANCHE, T. M. & DURRHEIM, K. 2006. Histories of the present: social science research in context. In: BLANCHE, T.M, DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. (eds.). Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

BRADY, M. C. 2015. Cultural considerations in play therapy with Aboriginal children in Canada. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 10(2): 95-109. [ Links ]

FERGUSON, H. 2017. How children become invisible in child protection work: Findings from research into day-to-day social work practice. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(4): 1007-1023. [ Links ]

FRANKLIN, A., BROWN, S. & BRADY, G. 2018. The use of tools and checklists to assess the risk of child sexual exploitation: Lessons from UK practice. Journal of child sexual abuse, 27(8): 978-997. [ Links ]

HANDLEY, G. & DOYLE, C. 2014. Ascertaining the wishes and feelings of young children: Social workers' perspectives on skills and training. Child & Family Social Work, 19(4): 443-454. [ Links ]

HOLLAND, S. 2001. Representing children in child protection assessments. Childhood, 8(3):322-339. [ Links ]

HUSBY, I. S. D., SLETTEBO, T. & JUUL, R. 2018. Partnerships with children in child welfare: The importance of trust and pedagogical support. Child & Family Social Work, 23(3): 443-450. [ Links ]

KEKAE-MOLETSANE, M. 2008. Masekitlana: South African traditional play as a therapeutic tool in child psychotherapy. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2): 367-375. [ Links ]

KOPROWSKA, J. 2014. Communication and interpersonal skills in social work: Transforming social work practice. Learning Matters. [ Links ]

MALOBOLA-NDLOVU, J. N. 2018. Functions of children's games and game songs with special reference to Southern Isindebele: The young adult's reflections. South Africa: University of South Africa. (Doctoral dissertation) [ Links ]

MARAIS, C. & VAN DER MERWE, M. 2016. Relationship building during the initial phase of social work intervention with child clients in a rural area. Social work, 52(2): 145-166. [ Links ]

MKHIZE, N. & MTHEMBU, M. 2019. Social workers' reflections on utilising indigenous games in counselling. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 31(2): 1-15. [ Links ]

MUNRO, E. 2001. Empowering looked-after children. Child and Family Social Work, 6(2): 129-137. [ Links ]

MUTAMBO, C., SHUMBA, K. & HLONGWANA, K.W. 2019. Child-centred care in HIV service provision for children in resource constrained settings: A narrative review of literature. AIDS research and treatment, 2019: ID 5139486 [ Links ]

NATIONAL DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT & UNICEF. 2012. Assessment tool for children in alternative care: assessment and training guide. South Africa. [ Links ]

OKPALAENWE, N. E. 2017. African approaches to psychotherapy. [Online] Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318532138_AFRICAN_APPROACHES_TO_PSYCHOTHERAPY [Accessed: 27/07/2021]. [ Links ]

O'REILLY, L. & DOLAN, P. 2016. The voice of the child in social work assessments: Age-appropriate communication with children. The British Journal of Social Work, 46(5): 1191-1207. [ Links ]

PARKER, J. 2017. Social work practice: Assessment, planning, intervention and review. 5th ed. SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

PÖLKKI, P., VORNANEN, R., PURSIAINEN, M. & RIIKONEN, M. 2012. Children's participation in child-protection processes as experienced by foster children and social workers. Child Care in Practice, 18(2): 107-125. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (RSA). 2005. Children's Act 38 of 2005. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944 (19 June 2006). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

REYNEKE, M. 2013. Children's right to participate: Implications for school discipline. De Jure, 46(1): 206-236. [ Links ]

REYNEKE, R. P. 2010. Social work values and ethics. In: NICHOLAS, L., RAUTENBACH, J. & MAISTRY, M. (eds.). Introduction to social work. Claremont: Juta and Company Ltd. [ Links ]

RUIZ-CASARES, M., COLLINS, T. M., TISDALL, E. K. M. & GROVER, S. 2017. Children's rights to participation and protection in international development and humanitarian interventions: nurturing a dialogue. The International Journal of Human Rights, 21(1): 1-13. [ Links ]

RYAN, D. P. 2001. Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory. [Online] Available: https://dropoutprevention.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/07/paquetteryanwebquest_20091110.pdf [Accessed: 27/07/2021]. [ Links ]

SARANTAKOS, S. 2012. Social research. Macmillan International Higher Education. [ Links ]

SHILLER, U. & STRYDOM, M. 2018. Evidence- based practice in child protection services: Do we have time for this? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 54(4): 407-420. [ Links ]

SPIES, G., DELPORT, R. & LE ROUX, L. 2017. Safety and risk assessment for the South African child protection services: Theory and practice. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 30(2): 116-127. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. 2005. Ethical aspects of research in the social sciences and human service professions. Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions, 3(1): 56-70. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS . 1989. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: UN Department of Public Information. [ Links ]

VAN NIJNATTEN, C. & VAN DOORN, F. 2013. The role of play activities in facilitating child participation in psychotherapy. Discourse Studies, 15(6): 761-775. [ Links ]

VAN VELSOR, P. 2004. Revisiting basic counselling skills with children. Journal of Counselling & Development, 82(3): 313-318. [ Links ]

VIAL, A., ASSINK, M., STAMS, J. M. & VAN DER PUT, C. 2020. Safety assessment in child welfare: A comparison of instruments. Children and Youth Services Review, 108:1-10. [ Links ]

WALTER, C. 2007. The story of Matthew: An ecological approach to assessments. Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care, 6(1): 45-53. [ Links ]

WASSENAAR, D. 2006. Ethical issues in social science research. In: BLANCHE, T.M, DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. (eds.). Research in practice: Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

WHITING, L. S. 2008. Semi-structured interviews: guidance for novice researchers. Nursing Standards, 22(23): 35-40. [ Links ]

ZOË LIFE INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS. 2018. Perceptions of health care providers on child friendly spaces. Unpublished report. [ Links ]