Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.57 n.4 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-967_923

ARTICLES

Nonhuman systems as a source of interactional resilience among university students raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers in Lesotho

Ms Simbai MushongaI; Prof Adrian D. van BredaII

IDepartment of Social Work & Community Development, University of Johannesburg, South Africa and Department of Sociology & Social Work, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho

IIDepartment of Social Work & Community Development, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Research on the resilience of young people who were raised by substance-abusing caregivers is limited. This study aims to explore the internal interactional processes between nonhuman systems and young adults raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers in Lesotho. Multiple in-depth interviews were conducted and a draw-and-write technique applied with 15 university students, six of whom described having interacted with diverse nonhuman systems in their environment. A grounded theory analysis generated two themes: (1) interacting with empowering messages from non-present writers (through songs and books) and inspirational speakers (through videos) and (2) interacting with imaginary friends and inanimate objects (dolls and tattoos) in order to enhance their resilience. Van Breda's interactional resilience approach, developed from person-in-the-environment perspective, and Margaret Archer's theory of agency were found to be useful in interpreting the findings. The implications of the study include the need for social workers' greater focus on young people's interactions with nonhuman systems for resilience building.

Keywords: adult children of alcoholics, alcohol-abusing, caregivers, internal conversations, interactional resilience, nonhuman

INTRODUCTION

A family caught up in alcohol addiction is often perceived as a "damaged", "split" or "fractured" family (Gudzinskiene & Gedminiene, 2011:163). Caregiver alcohol abuse has been associated with negative parenting behaviours, including intimidation and unreliability, inadequate monitoring and involvement, ineffective control of the child's behaviour and harsh discipline (Smith & Wilson, 2016).

Coming from chronically disorganised and distressing family settings, children of alcohol-abusing caregivers are at risk of a variety of physical, social, interpersonal, physiological, emotional and behavioural problems (Raitasalo & Holmila, 2017), such as depression, suicidal ideation, substance abuse and interpersonal difficulties (Raitasalo & Holmila, 2017). Possibilities of developing cognitive problems have been observed, including low capacity for learning and recall, limited academic achievement, and learning disability as well as an inability to learn from mistakes (Kuppens, Moore, Gross, Lowthian & Siddaway, 2020). Moreover, parental alcohol abuse has also been associated with attention and conduct problems at school and inconsistent attendance and higher school dropout rates in children (Raitasalo, 0stergaard & Andrade, 2021). Significant challenges in negotiating the transition from home to independent living have been reported among adult children of alcohol-abusing parents (Kim & Lee, 2011), who may themselves use and abuse alcohol and other substances (Smith & Wilson, 2016).

However, achieving "better-than-expected outcomes in the face or wake of adversity", which Van Breda (2018a:4) argues is the result of mobilising a range of resilience processes, is not something that society generally expects from children raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers. Most studies on young adults raised by alcohol-abusing parents tend to focus on negative outcomes experienced by such young people due to their biological and psychosocial risk factors (Raitasalo & Holmila, 2017), rather than their resilience.

Furthermore, among the studies on the resilience of adult children of alcohol-abusing caregivers, there is little research that addresses resilience processes that take place in the interaction between young people and other people or systems around them, which we refer to as "interactional resilience" (Van Breda, 2018b). A move from psychological resilience, which is the focus of much resilience research with this population, towards interactional resilience is much needed, so as to recognise the relationships and interactions that young people engage in as they deal with the challenges and risks of being raised by an alcohol-abusing caregiver.

Moreover, there appears to be no research on nonhuman systems as a source of resilience, especially among adult children of alcohol-abusing caregivers. A focus on the interaction of adult children of alcohol-abusing caregivers with nonhuman systems, rather than the more common human systems (such as friends, teachers and neighbours), may help practitioners in this field recognise previously hidden or unrecognised but vital sources of resilience.

The aim of this article, therefore, is to explore the interactions of resilient adult children of alcohol-abusing caregivers with nonhuman systems to understand what nonhuman systems they engage with and how these interactions operate to promote resilient outcomes. Participants for this study were 15 undergraduate students of the National University of Lesotho who had been raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers but were resilient, i.e. doing reasonably well academically and not abusing substances. Six of these participants mentioned interacting with nonhuman systems; these systems are the focus of this article. They reported having internal conversations with their laptops, online pre-recorded video, books, magazines, imaginary friends, dolls and tattoos.

In the following section, we provide a brief review of the extant research on the resilience of adult children of alcohol-abusing parents, human and nonhuman attachment relationships, and the theoretical framework of interactional resilience guiding this study. After accounting for the methodology, we present two themes that emerged through the analysis of data. We discuss these findings theoretically in relation to interactional resilience and internal conversations. After discussing the study limitations, we discuss implications for practice and conclude the article.

RESILIENCE IN ADULT CHILDREN OF ALCOHOL-ABUSING CAREGIVERS

While many adult children of alcohol-abusing caregivers are adversely affected by their experiences and go on to experience various problems, others evince resilient responses, with better-than-expected wellbeing and psychosocial functioning outcomes (Park & Schepp, 2015) Thus, while children raised by alcoholic caregivers are at higher risk of alcohol abuse, multiple emotional problems or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), there are many who grow up striving to adapt, endure and succeed in such traumatic settings (Lee & Williams, 2013); they can be termed 'resilient'.

Children with individual protective resources have been reported to show evidence of resilient outcomes under adverse situations. These resources include problem-solving skills (Goeke, 2017); constructive coping skills like self-disclosure, self-confidence and realistic rational appraisal of self and others (Hudson, 2016); ability to distract, dissociate and keep busy (Dayton, 2012); and ability to interact with others (Leary & DeRosier, 2012). Leisure activities have been reported as a significant protective factor in young adults raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers, including spending time in sedentary activities like watching television and listening to music and the internet (Serec, Svab, Kolsek, Svab, Moesgen & Klein, 2012).

Relational protective factors have also been found significant in promoting resilience among children raised by alcohol-abusers. A close bond with a caregiver or substitute caregiver outside the immediate family who can act as a role model has been reported to enhance resilient outcomes in children of alcohol-abusing parents (Goeke, 2017; McLaughlin, O'Neill, McCartan, Percy, McCann, Perra & Higgins, 2015). Having at least one close friend has also been reported to be a significant resilience protective factor in these young adults (Lotito-Meier, 2016). However, some children of alcohol-abusing caregivers have been reported to experience unstable attachment to family members, friends and romantic partners (Haverfield & Theiss, 2014).

Finally, a supportive community has been reported as a crucial protective resource in children of alcohol-abusing caregivers. This includes a community that provides positive role models (mentors, elders, supportive peers, social workers, teachers who can offer opportunities for academic achievements) as well as communities that are spiritually influential (Hebbani, Ruben, Selvam & Krishnamachari, 2020; McLaughlin et al., 2015). Social workers have also been found helpful in promoting the resilience of these young people, through providing family therapy, social skills training, coping skills as well as parent training and education (Lander, Howsare & Byrne, 2013).

HUMANS AND NONHUMAN ATTACHMENT RELATIONSHIPS

While resilience studies foreground the importance of human attachments, Mikulincer and Shaver (2012) observe that people also form attachment relationships with nonhumans, including inanimate objects, or even abstract concepts and places. Psychological research shows that objects can act as attachment figures, providing a sense of comfort and security in the absence of loved ones (Crossman, Kazdin, Matijczak, Kitt & Santos, 2020) - what Winnicott (1971:1) refers to as "transitional objects".

Comfort objects provide psychological strength and have powerful effects on the individual's emotional wellbeing (Bell & Spikins, 2018). They can prompt a sense of security and comfort similar to that of a caregiver or a loved one, by "providing a safe haven" and "secure base" to turn to when in need of emotional support (Bell & Spikins, 2018:109). Nonhuman systems can enhance emotional regulation and help integrate emotions with coherent thought, enabling the individual to maintain a positive mood (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). Through interacting with nonhuman objects, people may experience feelings that are similar to interacting with their human counterparts (Keefer, Landau & Sullivan, 2014). Objects are perceived to have agency, and thus have the potential to help children or young adults cope with adverse events and situations such as illness, loneliness or a family move (Taylor, Hulette & Dishion, 2010).

Nonhuman systems as resilience enablers among vulnerable children and youths have been written about only recently. For example, Morton, Bird-Naytowhow, Pearl and Hatala (2020), in their article entitled "Just because they aren't human doesn't mean they aren't alive", reported relationships with nonhumans (e.g., ants, water, storms, moonlight) as sources of resilience among urban indigenous youth in Canada. Doucet (2020) also reported nonhuman relationships, particularly with dogs, as a source of social capital support among youths who had aged out of care.

While human attachment with nonhumans is now accepted as normal interaction, in the past most cultures viewed human attachment with nonhumans as an indicator of psychopathology. For instance, tattoos are a taboo in some societies, while others associate them with incarcerated criminal gang members or people belonging to counter-cultural groups (Roggenkamp, Nicholls & Pierre, 2017).

Interactional resilience: A theoretical framework

The idea of interactional resilience in Van Breda (2018a) developed from the person-in-environment perspective, which suggests that a person cannot be understood independently of their environment. Individuals are who they are through their interaction with other people and with systems around them. Van Breda (2018a) argues that resilience is not so much about what is inside the young person, nor what is in the world around them, but rather what takes place in the interaction between young people and other people and the social environments that surround them. It is thus the patterns or dynamics of interaction that are of central importance for resilience.

Although such interactions would ordinarily be observable, because our study focuses on young people's interaction with nonhuman systems, these interactions will not take place in the observable external world, but rather through internal conversations. We are thus interested in these internal interactions and how they contribute to better-than-expected outcomes in the face or wake of growing up with an alcohol-abusing caregiver.

Margaret Archer's theory of agency, where internal conversations are regarded as playing a central role in mediating between structure and agency, may help understand these internal interactional processes with nonhuman systems. Internal conversation has been defined as a "continuous mental deliberation in and for action, which is at the heart of the reflexivity process" (Archer, 2003:91). Archer's argument rests on the premise that human beings can be both subjects and objects to themselves. She claims that humans have the capacity to formulate their thoughts, inspect them and respond to their internal conversation utterances as subject to object, a process she terms reflexivity. She further explains reflexivity as the way that humans do things like:

monitoring, self-evaluation and self-commitment ... through which we 'make up our minds' by questioning ourselves, clarifying our beliefs and inclinations, diagnosing our situations, deliberating about our concerns and defining our own project (Archer, 2003:103).

Reflexivity, therefore, considers "internal conversations as a mechanism that mediates between structure and agency; a way in which individuals can make sense of (or not) the social structures in which they live and their ability (or lack thereof) to engage as active agents in the creation of their adult lives" (Barratt, Appleton & Pearson, 2020:3). Hence internal conversations play a central role in individual agential functioning (Archer, 2012), as such deliberations "form the basis upon which people determine their future courses of action - always fallibly and always under their own descriptions" (Archer, 2007:4). Our conversations in this regard require no confirmation with others; they are lone inner dialogues, self-sustained and lead directly to action (Archer, 2003).

METHODOLOGY

Research approach and design

This study adopted an exploratory qualitative research approach, informed by a constructivist grounded theory design, which emphasises constructing rather than discovering theory from data (Charmaz, 2014). Rooted in symbolic interactionism (Corbin & Strauss, 2014), grounded theory focuses mainly on the ways people construct their worlds through their agency and social interactions, rather than on the ways people are influenced by social forces (Van Breda, 2015), hence its relevance to this article. Our main interest is to elucidate the interactional processes (or internal conversations) with nonhuman systems that enhanced resilience in students raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers.

Population and sampling strategy

The population comprised all National University of Lesotho (NUL) undergraduate students from the Faculty of Social Sciences (FSS). Non-probability purposive and snowball sampling (Carmichael & Cunningham, 2017) were used to sample 15 students from five departments in the FSS. Students from three departments volunteered to participate in this study, mostly from Sociology and Social Work. Participation criteria restricted the sample to students raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers, who were willing to share their lived experiences and who defined themselves as 'doing well' in some way, including academic achievement and non-abuse of substances. Upon being granted permission by the NUL Registrar to have access to such students, recruitment fliers providing information about who qualified to participate were distributed to FSS classes. This approach yielded ten participants using purposive sampling. To reach data saturation, a snowball strategy was used to recruit additional participants. The first interviewed participants were asked to suggest other participants who could be interviewed. Six of the 15 participants reported engaging in interactions with nonhuman systems and constitute the sample for this paper (see Table 4.1). Five of the six participants who interacted with nonhumans were in the Social Work programme and their fathers and uncles abused alcohol.

METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected by the first author in three interviews per participant using one-on-one semi-structured interviews and visual methods were used. In the first interview, both semi-structured interviews and a draw-and-write method were used. Participants were asked to draw-and-write their experiences and what they perceived increased their vulnerability to alcohol abuse and other negative experiences under the care of alcohol-abusing caregiver(s). They were further asked to identify, draw and describe the resilient outcomes achieved despite their adverse experiences.

After a few days, each participant was interviewed again. They were asked to identify and make drawings of whatever social-ecological resources were supportive of their resilience and to further describe the images through writing about the images and through brief verbal explanations (Theron, Stuart & Mitchell, 2011). It was in this interview that six participants mentioned nonhuman resilience resources.

In the third interview, using semi-structured interviews, participants explained the interactional processes that operated between them and these social-ecological resources in detail. It is in this interview that six participants revealed their internal conversations with the nonhuman systems that promoted their resilience.

Analysis and interpretation of data

All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For both the visual data and data collected through interviews, we used constructivist grounded theory methods of analysis (Charmaz, 2014). Data were coded in two stages: initial and focused coding (Charmaz, 2014). In the initial coding, we carefully studied participants' transcripts and conceptualised their ideas through line-by-line codes using gerunds (verbs ending in -ing) (Chametzky, 2019). The coded data from these initial encounters were then iteratively compared across interviews and participants before more data were collected. Memos were used throughout the research process to capture theoretical ideas, hence developing theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). From the initial codes, we subsequently developed focused codes based on recurring patterns of interactional resilience between participants and nonhuman systems.

Trustworthiness

Four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1985), namely credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, were used to ensure trustworthiness. Credibility was enhanced through member checking over the three interviews and peer debriefing by the second author (Charmaz, 2014). The input of the participants in developing themes from the visual drawings and interviews helped in enhancing credibility. An audit trail of research activities was maintained, including field notes, memos, theoretical sampling and coding (Marshall & Rossman, 2011), to enhance transferability. Dependability was enhanced by using an audit trail and by involving the second author and participants in evaluating the findings and the interpretations to ensure that they are supported by the data received from the participants. The code-recode strategy was also used to see if the two codings produce the same results (confirmability). Personal and professional selves (critical self-reflection of our assumptions, preconceptions, interests and positions) were enhanced by engaging in reflexivity, providing evidence from the literature that confirms interpretation of the data, as well as memo writing for confirmability purposes (Marshall & Rossman, 2011).

Ethics

Our study adhered to the code of ethics in research. Written authorisation from the NUL Registrar and a verbal approval by the Dean of FSS were granted to access the university premises and students. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the first interview. Participants were asked not to discuss any subject or draw any image they were not willing to share with researchers or the public. Participants were continuously reminded that they were not under pressure to draw, and that, should they be willing to try, the focus should not be on the quality of the drawing (Theron et al., 2011). The essence of ethics is to protect participants and their information, hence the need for informed consent, confidentiality, respect for privacy, right to withdraw from the study at any time, and ensuring that they are not placed at risk and putting measures in place to minimise risks. Arrangements were made in advance to refer participants for counselling if needed. Approval for the study was provided by the University of Johannesburg's Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee (REC-01-043-2019).

FINDINGS

The analysis generated two themes that show the interactional resilience processes between participants and nonhuman systems, namely (i) interacting with empowering messages from non-present songwriters, authors (written text) and inspirational speakers online by five participants, and (ii) interacting with imaginary friends and inanimate objects (imaginary friends, dolls and tattoos) by two participants.

Interacting with empowering messages from a non-present writer

Five of the six participants (excluding Ridge) narrated experiences of engaging with a writer - a person who is not present, but whose thoughts are mediated through songs, books or videos. Participants report extracting empowering messages from these writers and engaging with the message and/or writer in ways that build their capacity to withstand or overcome the negative impact of growing up with an alcohol-abusing caregiver. These interactions take place internally, through imaginary internal conversations with the writer, constituting what Van Breda (2018a) has called interactional resilience.

Summer, Joe and Mary reported engaging with non-present songwriters by listening to their music for distraction or support when there was physical or emotional abuse of family members by alcohol-abusing caregivers. Engaging with the messages of these non-present songwriters enhanced their reflexivity and introspection, which improved their resilience in the face and wake of adversity.

Summer mentioned extracting messages through conversing with one non-present songwriter whose message helped her deal with the guilt she had lived with for a long time. Summer had blamed herself for failing to protect her mother from the physical abuses of her father which left her mother with a deformed mouth. About that particular songwriter, Summer said she hears her telling her that even if she delayed in telling her father to stop physically assaulting her mother, she was glad that she finally talked to him and he stopped. Moreover, Summer says that the message she gets from that song enables her to tell herself that even though her mother has a deformity, the deformity doesn't matter anymore and that what matters now is that she is still alive and taking care of her. Summer said:

And there are these songs that when I listen to, I would feel ok, I am fine and I will overcome whatever challenges that I am facing... There is this song that says, 'Even if it is four days late, He is still the Lord'. And there was a time when I blamed myself for what happened to my mother. And listening to the music, it made me see that ok, it's fine, it's late, [and] the mouth has been dislocated. But the Lord made it possible to still have my mother even today. And I felt happy that at least I still have my mother. And whenever I need a mother to talk to, she is here to listen to me. So, this music helps me a lot.

These internal conversations assisted Summer to find some closure about the traumatic guilt she had been battling with for a long time. Thus, the internal conversation with the songwriter provokes reflexivity and understanding, as she would hear the songwriter telling her to be at peace and move on. Summer's interaction with the non-present songwriter takes place as an internal conversation. This constitutes an interactional process, albeit in her mind, that facilitates resilient outcomes.

Similarly, Joe described extracting messages and ideas from the songwriters he listened to. He used these ideas for developing his music career. Although Joe was pursuing a degree in social work, he has become a musician. He mentioned that the songs he composes are based on his lived experiences and ideas extracted from other songwriters. These experiences included witnessing his uncle, while under the almost daily influence of alcohol, physically abusing his children and wife, though not Joe and his sister.

Joe explained how internal conversations with songwriters and song writing improved his resilience:

Uuum, sometimes when such situations prevail and then I would go outside, listen to some music and if I do have a few words in my mind I would definitely write them down... It's basically about when I listen to music, I would try to extract a message out of it. And that particular message, I will try to understand that message through the situation that is happening... I would just incorporate it into the way how I understand this situation that is happening [the hostile situation at home], and how would I redirect it again so that I would give a direct picture of what is happening in my life and move with my life... And if I do so, I would normally consider my emotions... So, I just go to my room, I go to my laptop and I open my music production software and then I produce music. So, I would take the situation how it is and put it in other words so that I would be just in a general way that provides a positive message... I think that was one of my coping mechanisms. And itjust takes me to another world, just to another dimension that I will just forget about the problems and the situation.

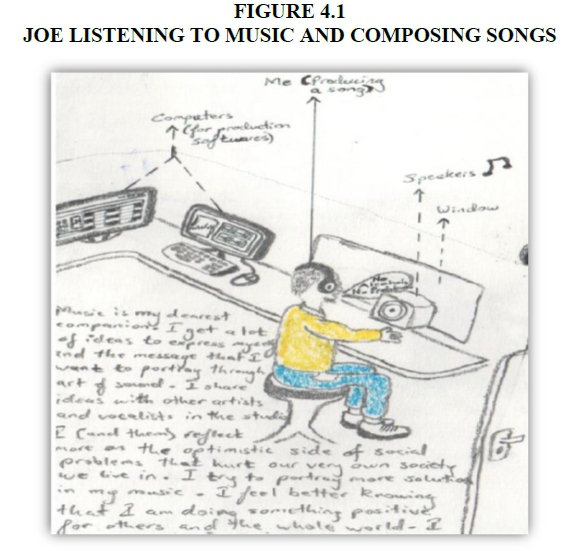

Figure 4.1 is a drawing by Joe of himself, illustrating how he would engage with music, extracting ideas and composing songs.

As illustrated in Figure 4.1, Joe speaks of the message of the song and the experience of the songwriter resonating with his experience, just as Summer reported previously. They both listen to the lyrics and interact with words, as well as the songwriter, even though the writer (singer) is not physically there, that is, they interact with a nonhuman system in a way that facilitates their resilience. Summer makes this resilience-enabling capacity of interacting with the songwriter and their lyrics clear in the following quotation:

There are songs that when you listen to them, it's like the other person was going through the worst situation than mine. So, when you listen to the song you try to reflect back to the problem and say at least this person, he or she might be in a very difficult situation more than mine. So, you listen to the music and you start like saying, ok, at least I am going through this, but this other person was going through that. And other music would be some sort of advices. And I would just say ok [a long hesitation] I don't know what I can say, but yes it did empower me.

Mary also confirms that the messages she extracts from an American musician's songs empower her and inspire her to do well. She said:

So as he sings things that are challenging, and I am in a challenging situation, I just get lost in thinking about what is in his music, [and] as I listen to music and I am paying attention to the lyrics, it just empowers me.

Just like Joe and Summer, Mary acknowledged that the ideas she extracts from this songwriter also help her to believe in herself and to believe in her capabilities to have a better future different from her parents. Responding to the question, "What do you get from engaging with Frank Ocean's music that helps you do well?" Mary replied:

We all try', where he opens up about his own beliefs and talks about beliefs like everyone should believe in something and that you feel lost in one particular thing, but there must be something that you believe in... well I believe for myself individually that the fact that I grew up in this kind of background at home, I am going to have a better home environment in the future for myself... I believe a lot... I believe in relationships, pure relationships.

Furthermore, reflecting on the gender-based violence at home, where her mother was a victim of assaults by her alcohol-abusing husband, Mary felt the need for empowerment. Even though her mother is educated and has a well-paying job, she chose to risk her life - due to societal norms and expectations -by staying in a married relationship with an alcohol-abusing husband who manipulates her. Cultural expectations are such that she is expected to endure the situation and obey her husband's demands (Sofolahan & Airhihenbuwa, 2013). Mary says she does not want this kind of life for herself and desires independence and self-management.

In addition to engaging with the messages from non-present songwriters, participants also engaged with the messages from non-present writers and speakers. Participants Mary, Lizzy and Linette demonstrated interactional resilience processes with non-present persons who were internally represented through videos and texts from books and magazines. Such internal conversations with text and video inspired them never to give up and enabled them to achieve better-than-expected outcomes. Reading, according to Shihab (2011:102), involves an interactive process whereby the reader "processes meaning through a set of mental processes", hence providing an ongoing interaction between the reader and the text.

Figure 4.2 shows Mary reading books, novels and magazines when the situation was unbearable at home because of her father's aggressive behaviour while under the influence. Her internal conversations with written texts distract her focus on the hostile situation. Mary said, "I read a lot. I say mostly because that's the one thing that I have been doing since these things started. His [her father's] drinking problem started back in high school."

Mary also describes having internal conversations with a non-present feminist Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, especially in her book, We should all be feminists. She explains that the author empowers her to stay strong and never to give up. Mary also mentions listening to empowering videos by the same author, who gives talks on, "culture, systems of oppression to both man and woman, how women and girls are not let to speak up a lot, and how men are taken more seriously than females" Engaging with feminist ideas from a feminist author and presenter is an internal interactional process that improves her resilience in the face of patriarchy. Mary said, "When sometimes I listen to her [Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's] talks on videos, it's just, it's empowering somehow, like she just affects me. The way she expresses these feminist things is the one that makes me feel empowered."

Like Mary, Linette also engaged in internal conversations with a non-present person through written text and video as part of her interactional processes of dealing with anger issues that she says were a result of hostile experiences with alcohol-abusing caregivers. Linette lived with a father and grandparents who were very aggressive under the influence of alcohol. When drunk, her father often verbally threatened to rape her. He also physically and emotionally abused her, and later rejected her and left Linette with severe anger issues.

Linette says she found her resilience through internal conversations with written texts by imaginative writers, or writers who had had experienced adversity in their lives. She engaged mostly with Deborah Smith Pegues's writings who, just like her, was abandoned by her father at a younger age: "I think I get my strength from other people's writings on anger issues and [Deborah], she is a lady who was abandoned by her father... [She] helps me."

Lizzy, another participant, similarly mentioned having internal conversations with a non-present person through text and video. Lizzy's father abused alcohol, resulting in almost daily aggressive behaviour. Lizzy's mother ran away from her abusive husband, leaving Lizzy and her younger brother in their father's care. Lizzy's father treated her young brother well (because he was a boy), but Lizzy was regularly physically abused until her mother helped her to escape to South Africa, where she was now living. Her mother had since married another man who also abused alcohol. Later, both her father and mother died, leaving Lizzy to parent her brother. Looking for a stable family to stay with, she moved from house to house until her uncle took her in for some time. That did not work out and she finally stayed alone while she was in high school. In this challenging life, Lizzy described searching for non-present persons to engage with and to inspire her to manage her situation:

Growing up in such a disadvantaged way I had to find ways of motivating myself. I knew I had to listen to people like Joel Osteen, Les Brown, Calvin Motebang; all of those motivational speakers [online videos]. I had to find somebody I would look up to and listen to their stories -Joyce Meyer - read and listen to their stories and say, "Oooh, so they did it. So, I can also do it." That was the only way for me to survive. It became a guide for me to do well.

There appear to be five interactional resilience processes involved in the participants' interaction with the empowering message of non-present writers (songwriters, authors and speakers). First, participants identified and extracted a message from the writer. Second, they related that message or the writer's experience to their own situation. Third, they engage in internal dialogue with the writer about the implications of their message for the participants' own situation. Fourth, this dialogue generates new insights and behaviours, particularly feeling empowered and motivated. And finally, this leads to better-than-expected outcomes, such as coping, doing well academically, changing their situation and avoiding alcohol abuse.

INTERACTING WITH IMAGINARY FRIENDS AND INANIMATE OBJECTS

In the absence of friends and relationships, and experiencing loneliness, Ridge and Linette interacted with imaginary friends and inanimate objects to keep them company as they imagined talking with them. Linette described forming alliances with imaginary friends and inanimate dolls, who enabled her to cope with her adverse situation. She engaged these objects in conversation just like she would dialogue with a human being. Ridge did the same with the tattoos that were etched on his neck; they were his resilience resources.

Linette had been exposed to difficult conditions under the care of her alcohol-abusing father and grandparents (both grandfather and grandmother). Her caregivers ill-treated her both physically and emotionally, damaging her self-esteem and leaving her unable to relate well with her peers. Her father and grandmother also exposed her to child labour from the age of six while her mother was working for the family in South Africa. In the absence of her mother, her father would constantly threaten to sexually assault her because he doubted his paternity. After Linette shared her father's intentions with her mother, her mother helped her to find refuge at her brother's home (Linette's uncle). At the uncle's home, she was offered a very small house where she stayed alone. Her father and grandparents later denied her access to other family members, including her two beloved young brothers, exposing Linette to terrible loneliness.

To deal with her loneliness and adverse situation, Linette reported creating and forming alliances with imaginary friends, who represented people she not only loved and valued, but also considered strong. Images of her good classmates influenced her imaginary friends' characters and these became her companions and coping mechanism in her solitude. Linette named her imaginary friends Lindy and Blessing. She consistently described her imaginary friends as allies who gave her company, advice, care and support.

When asked what it was about her imaginary friends that helped her do well, Linette responded "I still tell them what I want to do. I talk to them when I am happy and they rejoice with me. And when I am angry, I also talk to them..."

Linette's adverse life experiences left her with suicidal feelings. Interacting with Lindy and Blessing in such a lonely situation helped her deal with her anger issues and suicidal thoughts that constantly haunted her. Several times she contemplates suicide, but when those thoughts visited her, Lindy and Blessing, in her imagined conversations with them, will stop her. She said, "...when I try to kill myself, when I tell them, they will say, 'No please, don't do it!"

Linette indicated that her imaginary friend Lindy, though humble and sweet, would always tell her bluntly if she was wrong or right. Linette mentioned that she was always bitter and jealous of her peers and schoolmates who came from functional homes, and consequently often fought with them. She described her interaction about this with her imaginary friends:

In high school, I used to get irritated by other kids. So when I get home, I will be telling my imaginary friends that, "You know what, I don't like that girl. She is doing this and that. " And Lindy would just be telling me, "If you don't like her, she doesn't care and she doesn't even know that you don't like her. Stop punishing yourself. " And Blessing will be there smiling. And me knowing that at least I have a family that is there for me, and at least I have someone who understands me...

Sometimes when she did something wrong, especially to her peers at school, Linette would avoid sharing with her imaginary friends. Yet, those imagined conversations would still happen with her imaginary friends reprimanding her behaviour:

I am jealous of other kids when they are talking about their fathers and how their families are structured. And when I remember that my family is somehow disorganized, I become jealous and angry. So we fight, and when I am angry, I am very, I become very angry, like very... and I end up saying things that I wasn't supposed to say. Sometimes I don't have to tell Lindy or Blessing what happened. When I close my eyes, they will just come and tell me, "You didn't do this right, you should go and apologise."

Having no parental figure by her side to groom and guide her behaviour, internal conversations with strong imaginary friends enabled Linette to deal not only with her anger issues and loneliness, but also with the way she relates to and manages the outside world.

In addition to interacting with imaginary friends, Linette also mentioned having imaginary conversations with dolls that represented her two young brothers. She felt the need to have some physical attachment with her brothers after being denied access to them by her father and grandparents, so she came up with a creative plan to have her brothers by her side in the form of dolls that she could talk to daily. The dolls were "just like my brothers". Figure 4.3 is a drawing by Linette illustrating how she interacts with her doll brothers.

While living alone in her uncle's other small house, the imagination of her siblings being closer to her in the form of dolls, and the feeling of them listening to her, loving her, giving her support and encouraging her "to overcome anything", was a process that promoted her resilience. She said, "Ican tell them when I am angry just like my brothers... I could just talk to my dolls and imagine how my brothers would tell me to overcome anything."

Moreover, she expressed her resentment towards her father to her doll brothers. Because the brothers had also experienced their father's aggressive behaviour, they would comfort each other and advise each other to move on with their lives. Below is an example of the imagined conversations Linette would have with her doll brothers about their father and the resolution they would agree upon:

So there will be this time when I feel frustrated and I will go to my brothers [dolls] and I will tell them, "You know what, I don't like your father." And I know what my younger brother would say. He will just laugh and crack a joke... "He is still your father though." And the one who is in the middle willjust agree with me and say, "Yaaa, we shouldn't like that man." When the little brother smiles and cracks a joke because I love him, Ijust forget and be happy again. And when the middle one says, "We shouldn't be like that man," because we would be together, I will be knowing what my brother will be doing - the little one. He will be giving me that look that says, "No, don't! " So as a sister, I willjust say, "Ok guys, we have to think about something else... Somebody who is better than our father." And we just forget about the man who doesn't deserve to be in our life.

Much like Linette interacted with her inanimate objects - her dolls - Ridge interacted with his inanimate objects - tattoos that were etched on his neck for support. When Ridge's parents died when he was an infant, his grandmother took custody of him. They were staying in the rural areas of Lesotho, where they lived peacefully. However, in their community, some challenges could have affected Ridge's progress. For instance, boy children in their community had no interest in schooling. After circumcision, they would immediately go to work in South Africa in the mines. The schools, being far away, were not easily accessible. Because of these challenges, his grandmother negotiated with her daughter and husband for Ridge to stay with them in town so that he could attend school.

Unfortunately, Ridge's uncle abused alcohol and was very aggressive. His uncle and aunt had no time for their children and there was no communication between parents and children. In the absence of a supportive environment, Ridge had tattoos of things that he considered his pillars of support and strength etched on his neck. Figure 4.4 is an illustration of these tattoos.

The tattoo of his grandmother's name reminds him of his good childhood, of the support, love and happiness that he received from his grandmother when they used to stay together in the rural areas. Ridge said, "It assures me that there is still good life." Ridge explained:

So you know, when you are dealing with alcohol [in the family] sometimes along the way you lose hope, but you remember that my grandmother doesn't like this. Having grandmother's name here, like you regret like when you wake up you say, "No, this is not me. This is not who I am. This shouldn't happen at all!" So, it helps me a lot, because I think I will be doing more of that... Her name feels like I have a guardian angel with me.

Even though the grandmother lives many kilometres away from him, having her name on his neck, and interacting with a symbol of his grandmother, helped Ridge achieve better-than-expected outcomes. Imagining hearing his grandmother advising him to focus on achieving positive things in life and reminding him of the things that she expects of him, and how to live a healthy lifestyle, are resilience processes that enabled him never to give up.

Ridge also noted that since he was staying in an environment that deprived him of peace, he brought that peace to himself by having a tattoo of a bird. Engaging with the tattoo bird brought him some peace that he could not achieve under his uncle's care: "When you grow up in an environment where there is no peace, like you want peace more than anything. So, I can say it [the bird tattoo] gives me peace. Hey, looking at it, just knowing that I have this, you just feel peaceful." Ridge further stated that he would talk to his tattoos when he didn't understand the behaviour of his uncle and aunt: "I can say I talk to them, like sometimes when something related to the behaviour of your parents [uncle and aunt], you sit down maybe you don't know what to do."

Being spiritually minded, Ridge also 'prayed' to a tattoo cross etched on his neck for strength. Ridge said, "Sometimes I pray like to the tattoo cross. I pray, like I say whatever I want to say alone. And Ifeel that hope of Jesus listening, hiya. Talking to the tattoo cross gives me hope that one day I will do well. So I will pray." Hope helps individuals to uphold motivation and positive expectation provides a reason to continue living and may mediate the effect of depression (Dorsett, 2010).

Constant imaginary conversations with his tattoos, which are filled with hope, divine-seeking, peace-seeking and guidance-seeking are interactional resilience processes that enable Ridge to cope with his adverse situation and achieve positive outcomes. Emerging interactional processes that improve his resilience through imaginary internal conversations with tattoos include (i) imagining the grandmother's tattoo guiding him to have a dignified life style and to work hard despite the hardships he was currently experiencing, (ii) engaging with the tattoo cross through prayers while expressing his problems and needs and believing that Jesus was listening, imparted some faith and hope to achieve better-than-expected outcomes, and (iii) engaging with a bird tattoo which brought the peace that he needed in an unstable home and encouraged him never to give up.

This second theme differs from the first in that the interactions are not with actual (though non-present) people (writers, singers, speakers); instead, the interactions are with nonhuman systems that do not express actual thoughts or words, viz. imaginary friends, dolls and tattoos. While the interactional process in the previous theme started with an actual message from a writer, the interaction here starts with an imaginary conversation with a tangible or imagined object. It is thus a fully internal conversation, which in most of the examples provided is bi-directional - the imaginary friend or inanimate object 'speaks' back to the participant.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study show that some children raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers engage in internal conversations with nonhuman systems, and that these internal interactions constitute resilience processes, because they enable better-than-expected outcomes. Although most research on the resilience of vulnerable young adults focuses on human relationships as sources of resilience, this study and small number of other studies posit that nonhumans play an important "role in many social interactions - not simply as objects used by humans as interaction props, but as fully participating agents of action" (Cerulo, 2011:775). As stated by Mikulincer and Shaver (2012), human beings, particularly insecure individuals, can gain similar feelings of comfort and security from nonhuman systems (such as inanimate objects) as from human systems. Even though such objects are physically impassive, individuals experience them as having agency, cognition and compassion.

This study shows that, while all students raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers were exposed to challenging family environments, these young adults devised creative ways to cope, enabling them to achieve better-than-expected outcomes. Five (Ridge excluded) of the 15 participants described coping mechanisms that included imaginary internal interactions with non-present writers through the writers' thoughts mediated through songs, books or online videos. While engaging with those non-present writers, they reported extracting empowering messages in ways that deepened their resilience.

Through their internal interaction with non-present writer's thoughts, participants identified and extracted resilience-enhancing messages. As they related their situation to the writer's experience, they appropriated the writers' message for their own situation and coping mechanisms. As rightly argued by Archer (2012), internal conversations play a central role in the individual's agential function. Despite their adverse situations, the internal conversations instilled agential power in participants to identify patterns of their challenges, to exercise control of their situation, and to set future goals to achieve and to improve their life. Such reflexivity enabled them to achieve better-than-expected outcomes, such as avoiding alcohol, coping well academically and positively changing their situation.

Music has also been reported as empowering in many ways because of its ability to help individuals cope with stress, restore self-esteem, build resilience, and mentally prepare people for change and challenging situations (Baker, Tamplin, MacDonald, Ponsford, Roddy, Lee & Rickard, 2017; Travis, 2013). From these participants' perspectives, interaction with non-present writers through songs, books and online videos helped them to self-regulate their emotions, especially during those moments when the home environment resembled a war zone. The interactions also helped them to perceive their situation better and to come up with appropriate coping mechanisms. Through internal dialogues with the writer, they also felt empowered and motivated as they were able to relate their own situation with the writer's experiences, thus helping them achieve better-than-than expected outcomes. By being able to relate with the writer's experiences, they were inspired never to give up. These interactional processes enabled them to understand their own feelings and experiences as well as those of others.

Worth noting is the resourcefulness of two participants who had internal conversations with imaginary friends and inanimate objects that helped them to do well against all odds. The distinctiveness of this finding is that the interactions are not with actual (though non-present) people (writers, singers and speakers), but rather with nonhuman systems that do not express their thoughts, feelings or words. These included imaginary friends, dolls and tattoos. While in the interactional processes with non-present persons, the interactions started with actual message(s) from a writer, interactions with nonhuman systems started with an imaginary conversation with a tangible and imagined object. The internal conversation provided a bi-directional interaction with the imaginary friend (inanimate object) 'speaking' back. As argued by Archer (2003), human agency is made possible by the person's capacity for reflexivity and the regular exercise of mental ability to consider themselves in relation to their context. Such thoughts are vital since they form the basis upon which people determine their future courses of action. Thus, having internal conversations with imaginary friends and objects made it possible for the participants to identify and define their concerns - those areas that matter most and those that are personally significant to them (Hung & Appleton, 2016).

Having imaginary dialogues with imaginary friends and inanimate objects - dolls and tattoos that represented influential people and things in their lives - made it possible to form aspects of their identities as well as emerging identities (Hung & Appleton, 2016). These conversations helped them to undertake deep reflections about their own situations, what they cared about most, and how their countless concerns and commitments might come to fruition or not. Such deliberations enabled them to achieve better-than-expected outcomes. As argued by Gentry and Alderman (2007), objects like tattoos have some therapeutic connections as they serve to assist individuals express and cope with trauma experiences. They facilitated empowerment, instilled hope, and helped to solidify and communicate meaningful stories, thus enabling the participants to achieve better-than-expected outcomes despite their adverse situations.

LIMITATIONS

Our sample size of five participants who interacted with non-present writers and speakers, and two who had internal conversations with imaginary friends and objects was small, making it difficult for the results to be generalised. A further limitation is that there was no interview question that specifically focused on the interactions between participants and nonhuman systems in our interview guide. It is therefore possible that some participants who might have interacted with nonhuman systems could have considered such interactions insignificant if not awkward, and decided not to mention this during the interviews. A direct question could have helped to bring out such interactions directly.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study makes a valuable contribution to the role played by nonhuman systems and objects as resilience resources among young adults in Lesotho, where there is no research on the subject. Noteworthy is the internal conversations with nonhuman systems in promoting resilience in such groups especially in young adults raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers.

It will be important for future researchers to expand the size of the sample to test and confirm our findings. We further recommend extended research on nonhuman systems to confirm and elaborate on the findings of this study. It will also be important to carry out comparative studies of interactional resilience processes involving humans, on the one hand, and nonhumans, on the other hand, to strengthen and consolidate the framing of interactional resilience theory. Margaret Archer's theory of agency, where internal conversations are viewed as playing a fundamental part in mediating between structure and agency, should also be further expounded to understand these internal interactional processes with nonhuman systems among this population.

It is also essential for social workers and other practitioners to recognise previously hidden or unrecognised but vital sources and resources of resilience, including nonhuman relationships that increase the resilience of vulnerable children and young adults. Social workers work extensively with substance abusers, with children in child welfare settings and in educational settings (both schools and universities). This study is thus of direct practice relevance for all these social workers. While still building resilience resources within and around such clients, social workers can also introduce, normalise and even encourage the use of non-human systems as potential sources of strength and capacitation. Such resources are readily available and may already be in play, but not recognised by the client or their social worker. Social workers could also provide a non-human object (such as a doll or clay animal) to a client, with a narrative about this being a symbol of the social worker or some other important present or absent person in the client's life, as a transitional object (Winnicott, 1971).

This study therefore concludes that as much as we may invest in our supportive relationships with humans, nonhuman systems also can fulfil a unique and significant role in improving resilience in vulnerable young adults, such as those raised by alcohol-abusing caregivers. The imaginary internal conversations they had with non-present persons in music and written texts, as well as inspirational speakers online, were interactional resilience processes that inspired them never to give up. Moreover, their engagement with representational objects through internal conversations was also an interactional resilience process that enabled them to achieve better-than expected outcomes. From this inquiry, it is plausible to conclude that resilience needs to be seen as an interactional process situated in specific circumstances, rather than primarily as a quality of individual character.

REFERENCES

ARCHER, M. S. 2003. Structure, agency and the internal conversation. United Kingdom Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

ARCHER, M. S. 2007. Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

ARCHER, M. S. 2012. The reflexive imperative in late modernity. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

BAKER, F. A., TAMPLIN, J., MACDONALD, R. A., PONSFORD, J., RODDY, C., LEE, C. & RICKARD, N. 2017. Exploring the self through songwriting: An analysis of songs composed by people with acquired neurodisability in an inpatient rehabilitation program. The Journal of Music Therapy, 54(1): 35-54 [ Links ]

BARRATT, C., APPLETON, P. & PEARSON, M. 2020. Exploring internal conversations to understand the experience of young adults transitioning out of care. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(7): 869-885. [ Links ]

BELL, T. & SPIKINS, P. 2018. The object of my affection: attachment security and material culture. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture, 11(1): 23-39. [ Links ]

CARMICHAEL, T. & CUNNINGHAM, N. 2017. Theoretical data collection and data analysis with gerunds in a constructivist grounded theory study. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 15(2): 59-73. [ Links ]

CERULO, K. A. 2011. Social interaction: do non-humans count? Sociology Compass, 5(9): 775-791. [ Links ]

CHARMAZ, K. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage. [ Links ]

CHAMETZKY, B. 2019. Coding in classic grounded theory: I've done an interview; now what? Sociology Mind, 6(4): 163-172. [ Links ]

CORBIN, J. & STRAUSS, A. L. 2014. Basics of qualitative research. New York: Sage. [ Links ]

CROSSMAN, M. K., KAZDIN, A. E., MATIJCZAK, A., KITT, E. R. & SANTOS, L. R. 2020. The influence of interactions with dogs on affect, anxiety, and arousal in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(4): 535-548. [ Links ]

DAYTON, T. 2012. The ACOA trauma syndrome: The impact of childhood pain on adult relationships. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, Inc. [ Links ]

DORSETT, P. 2010. The importance of hope in coping with severe acquired disability. Australian Social Work, 63(1): 83-102. [ Links ]

DOUCET, M. 2020. All my relations: Examining nonhuman relationships as sources of social capital for Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth 'aging out' of care in Canada. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience, 7(1): 139-153 [ Links ]

GENTRY, G. W. & ALDERMAN, D. H. 2007. Trauma written in flesh: Tattoos as memorials and stories. In: HIDALGO, D. A. & BARBER, K. (eds.). Narrating the storm: Sociological stories of Hurricane Katrina. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars. [ Links ]

GOEKE, J. 2017. Identifying protective factors for adult children of alcoholics. St. Catherine University and the University of St. Thomas. (Master of Social Work Clinical Research Paper) [ Links ]

GUDZINSKIENE, V. & GEDMINIENE, R. 2011. Understanding of alcoholism as family disease. Social Education/Socialinis Ugdymas, 14(25): 33-45. [ Links ]

HAVERFIELD, M. C. & THEISS, J. A. 2014. A theme analysis of experiences reported by adult children of alcoholics in online support forums. Journal of Family Studies, 20(2): 166-184. [ Links ]

HEBBANI, S., RUBEN, J. P., SELVAM, S. & KRISHNAMACHARI, S. 2020. A study of resilience among young adult children of alcoholics in Southern India. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(3): 339-347. [ Links ]

HUDSON, K. 2016. Coping complexity model: Coping stressors, coping influencing factors, and coping responses. Psychology, 7(3): 300-309. [ Links ]

HUNG, I. & APPLETON, P. 2016. To plan or not to plan: The internal conversations of young people leaving care. Qualitative Social Work, 15(1): 35-54. [ Links ]

KEEFER, L. A., LANDAU, M. J. & SULLIVAN, D. 2014. Non-human support: Broadening the scope of attachment theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(9): 524-535. [ Links ]

KIM, H. K. & LEE, M. H. 2011. Factors influencing resilience of adult children of alcoholics among college students. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 41(5): 642-51. [ Links ]

KUPPENS, S., MOORE, S. C., GROSS,V., LOWTHIAN, E. & SIDDAWAY, A. 2020. The enduring effects of parental alcohol, tobacco, and drug use on child well-being: A multilevel meta-analysis. Development & Psychopathology, 32(2): 765-778. [ Links ]

LANDER, L., HOWSARE, J. & BYRNE, M. 2013. The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Social Work in Public Health, 28: 194-205. [ Links ]

LEARY, K. A. & DEROSIER, M. E. 2012. Factors promoting positive adaptation and resilience during the transition to college. Psychology, 3(12): 1215-1222. [ Links ]

LEE, H. & WILLIAMS, R. A. 2013. Effects of parental alcoholism, sense of belonging, and resilience on depressive symptoms: A path model. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(3): 265-273. [ Links ]

LINCOLN, Y. S. & GUBA, E. G. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, USA: Sage. [ Links ]

LOTITO-MEIER, V. 2016. Resiliency and protective factors in adult children of alcoholics: A narrative review. St. Cathrine University, St. Paul, MN. (Masters' thesis) [ Links ]

MARSHALL, C. & ROSSMAN, G. B. 2011. Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage. [ Links ]

MCLAUGHLIN, A., O'NEILL, T., MCCARTAN, C., PERCY, A., MCCANN, M., PERRA, O. & HIGGINS, K. 2015. Parental alcohol use and resilience in young people in Northern Ireland: A study of family, peer and school processes. Policy, 12: 1-147. [ Links ]

MIKULINCER, M. & SHAVER, P. R. 2012. Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4): 259-274. [ Links ]

MORTON, D., BIRD-NAYTOWHOW, K., PEARL, T. & HATALA, A. R. 2020. "Just because they aren't human doesn't mean they aren't alive": The methodological potential of photovoice to examine human-nature relations as a source of resilience and health among urban Indigenous youth. Health & Place, 61: 102-268. [ Links ]

PARK, S. & SCHEPP, K. G. 2015. A systematic review of research on children of alcoholics: Their inherent resilience and vulnerability. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24: 1222-1231. [ Links ]

RAITASALO, K. & HOLMILA, M. 2017. Parental substance abuse and risks to children's safety, health and psychological development. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 24(1): 17-22. [ Links ]

RAITASALO, K., 0STERGAARD, J. & ANDRADE, S. B. 2021. Educational attainment by children with parental alcohol problems in Denmark and Finland. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 38(3): 227-242. [ Links ]

ROGGENKAMP, H., NICHOLLS, A. & PIERRE, J. M. 2017. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: How talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(3): 148-158. [ Links ]

SEREC, M., SVAB, I., KOLSEK, M., SVAB, V., MOESGEN, D. & KLEIN, M. 2012. Health-related lifestyle, physical and mental health in children of alcoholic parents. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31(7): 861-870. [ Links ]

SHIHAB, I. A. 2011. Reading as critical thinking. Asian Social Science, 7(8): 209-218. [ Links ]

SMITH, V. C. & WILSON, C. R. 2016. Families affected by parental substance use. Journal of the American of Pediatrics, 138(2): 1-13. [ Links ]

SOFOLAHAN, Y. A. & AIRHIHENBUWA, C. O. 2013. Cultural expectations and reproductive desires: Experiences of South African women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA). Health Care for Women International, 34(4): 263-280. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, M., HULETTE, A. C. & DISHION, T. J. 2010. Longitudinal outcomes of young high-risk adolescents with imaginary companions. Developmental Psychology, 46(6): 1632-1636. [ Links ]

THERON, L. C., STUART, J. & MITCHELL, C. 2011. A positive, African ethical approach to collecting and interpreting drawings. In: THERON, L., MITCHELL, C., MITCHELL, C., SMITH, A., SMITH, A. & STUART, J. (eds.). Picturing research: Drawing as visual methodology. Boston, USA: SensePublishers. [ Links ]

TRAVIS, R. 2013. Rap music and the empowerment of today's youth: Evidence in everyday music listening, music therapy, and commercial rap music. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 30(2): 139-167. [ Links ]

VAN BREDA, A. D. 2015. Journey towards independent living: As grounded theory investigation of leaving the care of Girls & Boys Town, South Africa. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(3): 322-337. [ Links ]

VAN BREDA, A. D. 2018a. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Social Work / Maatskaplike Werk, 54(1): 1-18. [ Links ]

VAN BREDA, A. D. 2018b. 'We are who we are through other people' : The interactional foundation of the resilience of youth leaving care in South Africa. Professorial Inaugural Lecture. [Online] Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TXCAMThmbbA. [ Links ]

WINNICOTT, D. W. 1971. Playing and reality. London, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]