Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Social Work

versión On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versión impresa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.57 no.4 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-965

ARTICLES

Measuring the need for educational supervision amongst child protection social workers: an exploration

Ms Balebetse Maria MokoeleI; Prof. Mike (ML) WeyersII

ISocial worker, Department of Social Development, Ventersdorp, South Africa

IISocial Work Division, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Supervision is a potentially effective tool for empowering social workers to perform their duties to their optimal abilities. There are, however, indications from research and practice that this potential has not always been fully realised in South Africa. This especially applies to educational supervision. The aim of the study on which this article is based was to help address this deficiency by profiling the educational supervision needs of a group of child protection social workers of a provincial department of social development. Its results could be used to address deficiencies not only in that province, but also further afield.

Keywords: educational supervision, child protection, child protection social worker, Department of Social Development, social work supervision, supervision

CONTEXTUALISATION

Social work supervision has been part of the profession since its inception. However, since then it has developed a separate methodology that is substantively different from the process and meaning that are usually associated with the concept of supervision. Instead of referring only to an administrative function, it now also encompasses an educational or formative function, as well as a supportive or restorative function (Engelbrecht, 2014). These three functions are reflected in the following definition as adopted by the Department of Social Development (DSD) and the SA Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSp) in 2012:

Social work supervision is an interactional and interminable process within the context of a positive, anti-discriminatory relationship, based on distinct theories, models and perspectives on supervision whereby a social work supervisor supervises a social work practitioner by performing educational, supportive and administrative functions in order to promote efficient and professional rendering of social work services (DSD & SACSSP, 2012:10).

Supervision is a potentially effective tool in empowering especially newly qualified social workers with the additional knowledge and skills required to serve individuals, families, organisations and communities even more effectively. However, there are strong indications from research and practice that this potential is not always fully realised in South Africa, especially as far as the educational function of supervision is concerned (DSD & SACSSP, 2012; Engelbrecht, 2010; Mbau, 2005; Pullen-Sansfacon, 2014). This necessitates further research into this field in general and especially into educational supervision.

The basic goal of the study on which this article is based was to contribute to this field by identifying and profiling the educational supervision needs of a group of social workers of the North-West Province's Department of Social Development. The group selected was the Department's child protection social workers.

The need for more specialised research into supervision in the child protection field came sharply into focus with the enactment of the Children's Act 38 of 2005 (RSA, 2005). This Act placed considerable new demands on social workers (DSD, 2010). Its promulgation also coincided with sociodemographic changes in the country (e.g. an increase in AIDS orphans), which led to a sizeable increase in the number of children in care. These trends, coupled with a resultant increase in new entrants into the social work profession and child protection field, contributed to a need for the more effective supervision of child protection social workers (DSD & SACSSP, 2012; Engelbrecht, 2013).

The sheer number of cases to attend to, coupled with the diversity of expectations in the child protection and related fields, is often experienced by practitioners as overwhelming. In May 2020, for example, social workers had to attend to 355,609 children in foster care, of whom 28,495 resided in the North-West province (SASSA, 2020). In the DSD, the practitioners' main activities cover the handling of all facets of foster care cases, including intake, new children's court hearings, foster care supervision services and reconstruction services to biological parents. The same practitioners also have to attend to the other programmes of the Department (e.g. services to women, to older persons, to people living with HIV and Aids etc.) (DSD, 2020). It is expected of them to perform well in all their assigned duties and to apply relevant and up-to-date theories and policies to guide their work. These outcomes can only be achieved if evidence-based and effective supervision services are in place.

The current trends do not only place a heavy burden on the shoulders of the frontline social worker, but on their supervisors as well. In South Africa social work supervisors are responsible for their supervisees and are held accountable for the latter's actions (SACSSP, 2007). Hence, they need to ensure that the services delivered to recipients are in line with set policies and guidelines. It they fail at this responsibility, Section 5.4.I(a) of the Policy Guideline for Course of Conduct, Code of Ethics, and the Rules for Social Workers (SACSSP, 2007) comes into play. This section states that the supervisor could be held liable in an instance where a complaint of alleged unprofessional conduct is lodged against his or her supervisee (social worker). Supervisors can only comply with these responsibilities if they too are equipped with evidence-based knowledge and skills.

It is clear from the above that there is a need for specialised research into the educative, supportive and administrative supervision needs of social workers in the employ of the DSD in particular and other sectors in general. It would, however, not be possible to cover all three functions within the scope of one article. The discussion will consequently be limited to the educational supervision of child protection social workers. These are practitioners whose primary function it is to deliver preventative, counselling, rehabilitation and placement services to destitute, neglected or abused children, or children who may be at risk or in need in other ways (National Association of Social Workers, 2012; RSA, 2005; Social Work Degree Guide, 2017).

The nature and results of the empirical study on which this article is based will be covered in more detail.

AIM

The aim of the study was to ascertain the current nature of, and needs for, educational supervision as experienced by child protection social workers in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District of the North-West province's Department of Social Development.

To realise this aim, the following four objectives were pursued:

• to profile the educational supervision that a group of child protection social workers in the District currently receives;

• to profile the education supervision needs of the same group;

• to compare the two profiles with each other and with social work literature; and

• to utilise the results of the comparisons to make recommendation and provide guidelines on how educational supervision in the North-West province's Department of Social Development could be improved.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The primary research design used in the study could be typified as a cross-sectional quantitative survey, also known as a cross-sectional analysis, transversal study or prevalence study (Lavrakas, 2008). It basically involved the use of a survey questionnaire "administered at a single point in time from a sample drawn from a specified population" (Dumont &Sumbulu, 2010:208). The population referred to will be described in more detail next.

POPULATION AND RESPONDENTS

The target population for the study was all the frontline child protection social workers with less than 10 years' practice experience and who were employed at three service points of the DSD in the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District of the North-West province. One of the reasons for this demarcation was that it could be accepted that they would all still be under supervision because of the trend that practitioners only qualify for a supervisor post and a promotion to that rank after 10 years' experience (albeit that the minimum requirement is five years) (DSD & SACSSP, 2012). Another was that, because of the DSD's structure, the targeted groups would not only be representative of the particular districts, but also fairly representative of the particular cadre within the provincial department as a whole. This provincial department was the 'universe' in the study.

It was intended to involve all the Grades 1 to 3 social workers in the selected service points who met the selection criteria. These service points were Maquassi Hills, Potchefstroom and Matlosana (Klerksdorp). At the time of the empirical study (December 2019/January 2020), there were 101 potential respondents. Of these, 63 (62.38%) ultimately completed the questionnaire.

The study applied the Kaiser, Meyer, Olkin (KMO) formula to test whether this sample was adequate for factor analysis (Glen, 2016). It produced a score of 0,781. This indicates that it was more than adequate for the purposes for which the research was undertaken (Glen, 2016).

RESEARCH PROCESS

The entire process followed in the study is summarised in Table 1. It should be noted that some of the phases overlapped in terms of their timeframes.

Only some of the more pertinent elements of the research process as contained in Table 1 will be looked at in more detail.

In the study a questionnaire was used to "obtain the fact and opinions about a phenomenon" (Delport & Roestenburg, 2011:186), in this case educational supervision, from the selected group of social workers. In this context, a questionnaire was seen as "a document containing questions and/or other types of items designed to solicit information appropriate for analysis" (Rubin & Babbie, 2007:246).

The biggest challenge in finding or developing a questionnaire was to have one that would fit the unique setting in which the research was being conducted (i.e. a South African provincial "welfare" department) and a unique population (i.e. child protection social workers), as well as one that would at the same time be reliable, valid and appropriate for local circumstances. No single instrument could be found that met all these requirements. The study's questionnaire was consequently based on several instruments utilised in international supervision-focused studies, as well as two from South Africa.

The South Africa studies by Mbau (2005) and Du Plooy (2011) were the only recent ones which could be found that specifically dealt with supervision within a so-called provincial "welfare" department and also contained some or other form of measuring instrument or questionnaire. Both studies were, however, undertaken before the 2012 adoption of the Supervision Framework by the National Department of Social Development (DSD & SACSSP, 2012). This meant that some of their questions and sections were outdated. The questionnaires did, however, give indications of how questions could be 'indigenised' to better address unique South African circumstances.

The other questionnaires that were used as a basis in developing the questionnaire were the following:

• Bell, L. 2010. Child welfare professionals' experience of supervision (UK);

• Crisp, B. R. and Cooper, L. 2008. The content of supervision scale (USA);

• Mak, M.A. 2013. Supervision training needs: the perspectives of social work supervisees (USA);

• Parente, M. 2011. Experience of supervision scale (USA).

The instrument that was developed for the study consisted of seven sections. Three predominantly contained descriptive questions and their results were consequently interpreted by means of descriptive statistics. The other four sections took the form of independent scales that were interpreted by means of inferential statistics.

In the development of the instrument, five members of North-West University's MSW in Child Protection class were used to review the draft questionnaire. Their tasks as a panel of experts were to assess the face validity of questions, as well as to identify questions that were unclear, ambiguous, etc. and to make recommendations in this regard. The feedback received was used to adapt questions or to eliminate those that did not meet the requirements or were deemed unnecessary. The instrument was then submitted to an expert of the Statistical Consultation Services of North-West University to verify whether it complied with their requirements, which it did.

The data generated by the questionnaire were subjected to a statistical analysis by the Statistical Consultation Services through the use of the SPSS and statistical power calculations. It included the calculation of the Cronbach alpha coefficients (α) of scales, and the means (X) and average standard deviation (σ) of items.

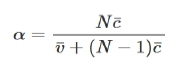

Four of the questionnaire's sections were specifically designed to function as individual scales. These covered the (perceived) need for social work supervision (see Table 5), the current administration of these services at the selected service points (see Table 10), the general nature of supervision received (see Table 11), and then a more focused look at the educational supervision they received (see Table 12). The Cronbach alpha coefficient (α) for each scale was calculated to determine its reliability in terms of the Likert scale components of the questionnaire (Field, 2009; Gravetter & Forzano, 2003). The formula applied for this purpose was:

Where Ν = the number of items,

Where Ν = the number of items,  = the average inter-item covariance

= the average inter-item covariance

among the items and  the average variance (UCLA Institute for Digital Research & Education, 2019).

the average variance (UCLA Institute for Digital Research & Education, 2019).

According to Statistics Solutions (2020), the "general rule of thumb is that a Cronbach's alpha of .70 and above is good, .80 and above is better, and .90 and above is best." This view is similar to those of Ellis and Steyn, (2003), Field (2009) and Jackson (2003). In the study, two of the scales were above 0.8 and another two above 0.9. They could therefore be viewed as reliable to very reliable.

FINDINGS

The data produced by the study were much more robust, valid and reliable than originally expected. However, because of length constraints, only the most important findings will be reported on here. These will be structured according to the sections and themes covered by the questionnaire. For ethical reasons, specific service points will not be identified by name.

Socio-graphic profile of respondents

All three service points were sufficiently represented in the responses with 20 (31.75%) coming from Area 1, 23 (36.5%) from Area 2, and 20 (31.75%) from Area 3. All the respondents had a 4-year BSW degree as their highest qualification. Profiles of their age, number of years of social work experience and rank are summarised in Table 2.

It could be concluded from the data in Table 2 that the study did indeed encompass the type of respondents that it originally targeted inasmuch as that the majority of respondents (35/57.1%) had fewer than seven years of practice experience and fell into the under 35 years of age group (32/50.8%). The only anomaly was the two (3.2%) with the rank of "senior social worker" who also responded. The probable reason why they still received supervision was that they had moved from another section and were new to the child protection field. Whatever the case might be, their small number (2/3.2%) would not have had a significant effect on the outcome of the study.

Training in social work supervision and policy

One component of the questionnaire dealt with the university-based and inhouse training that the respondents had received on social work supervision and policy. It included both a quantitative and qualitative component. The reason for this combination of question types was to gain a better understanding of the nature of and reasons for the respondents' answers. Their responses to the quantitative questions are summarised in Table 3.

The answers to the first question were somewhat perplexing. They do not correlate with the fact that the inclusion of supervision in undergraduate social work training programmes has been mandatory since the publication of BSW Exit Level Outcome 21 in Government Gazette No. 24362 of 7 February 2003 (South African Qualification Authority, 2003). A similar requirement also applies to training institutions who after 2015 started to migrate to competency-based training as required by the Council on Higher Education (2015). Based on the fact that only 11 (17.5%) respondents had been practising for nine or more years (see Table 2.1) and also that the statistical analysis indicated no significant correlation between years of practice and university training in supervision, it can only be concluded that the 28 respondents had simply forgotten that they had received such training.

The 11 (17.5%) respondents who indicated that they received on-the-job training in social work supervision were asked to describe this training briefly. Some indicated that it consisted of presentations by colleagues who had attended supervision training before. Others responded that they attended supervision workshops organised by their employer. From these and other responses it can be concluded that a structured in-service social work supervision training programme was somewhat lacking.

Only 14 (22.2%) respondents indicated that their employer provided them with its formal supervision policy. In a follow-up question, however, they were also asked how well they knew this policy. Their responses are summarised in Table 4.

The analysis of the data indicated that a distinction should be drawn between the physical issuing of the policy document and knowledge of its contents. It would seem as if the majority of respondents (48/76.2%) did not have the document in their possession. This is a deficiency that should be addressed by the employer.

Although only one (1.6%) respondent did not know of the existence of such a document and another 25 (39.7%) did not know its contents, the knowledge of at least 32 (50.8%) of the others varied between "a bit" to "very well". This result should be juxtaposed with the results of the statistical analysis that indicated a direct correlation between years of practice (see Table 2:2) and knowledge levels (see Table 4). This showed that respondents with more years of practice knew the policy significantly better. This indicates that employers should make a concerted and continuing effort to train their employees in the policy.

The need for social work supervision

The second section of the questionnaire was intended to find answers to the question as to whether the respondents thought that supervision could empower them professionally and was indeed necessary. It thus measured their attitudes towards social work supervision. This would provide a baseline against which their views and experience of supervision within their employer organisation could be measured.

The section contained seven statements. Each respondent had to indicate on a Likert-type scale whether they "Strongly disagreed", "Disagreed", "Agreed" or "Strongly agreed" with each statement. The questions and the responses they generated are summarised in Table 5.

The statistical analysis of the responses (see Table 5) indicated that the scale had a Cronbach alpha coefficient (α) of 0.848 and could therefore be viewed as very reliable. In the calculations, the responses to the first two items (see Table 5: I1, I2) were reversed to accommodate the fact that they represented 'negatively' formulated questions.

In general, the respondents exhibited a very positive stance towards supervision. For example, they did not see it as an insult to professionals or a waste of money (see Table 5: Q1 & Q2). The vast majority also regarded it to be a useful tool for enhancing practitioners' efficiency, effectiveness and professionalism (see Table 5: Q3, Q4 & Q6) and to monitor work performance (see Table 5: Q5). However, an analysis of the individual responses indicated that three individuals tended to hold an opposing view. Although this did not have a significant influence on the overall trend, it had to be considered in the interpretation of the data generated by other questions.

The primary conclusion that could be reached from the analysis of the data produced by Section 2 was that most respondents viewed supervision in a positive light. This implies that possible negative responses to the state of supervision in the selected service points could not be attributed to an initially negative stance, but rather to other factors.

Profile of supervision received

The third core section of the survey was intended to profile the supervision received by the respondents and their experience of this service. It was not designed as a scale, but rather as several separate questions. Their responses will be clustered in accordance with the three themes covered by the section.

The first theme was the amount of supervision received. In this regard, respondents were asked to indicate how many times they had received supervision in the previous 12 months and their feelings regarding this amount of supervision. Their responses are summarised in Table 6.

There are no hard and fast rules regarding the amount of supervision that a beginner child protection social worker should receive. According to the DSD and SACSSP (2012) Supervision Framework, however, it is mandatory that all newly qualified social workers should receive supervision during the first year of practice on at least a fortnightly basis, after which the frequency may be reduced to at least once a month. The British Association of Social Workers (BASW) and Commonwealth Organisation for Social Work (CoSW), on the other hand, recommend that supervision should be done "weekly for the first six weeks of employment for a newly qualified social worker, fortnightly for the next six months, and at least monthly after that" and that each session should "last at least an hour and a half of uninterrupted time" (Godden, 2012:10). These views would, on average, place supervision within the range of 12 to 17 formal sessions per annum for the first seven years of employment.

Both the average number of sessions (±14) reported by the respondents and the mean (x = 3.27 - i.e. 1120 times) generated by the survey (see Table 6: Q1) indicated that they did on average have the appropriate number of supervision sessions. What was striking, however, was the wide range of responses with 20 (31.7%) having had four or fewer sessions and two (3.25%) more than 31. The reason for this range is probably the profile of respondents (see Table 2), which indicated that 11 had nine or more years of practice experience and six less than two.

The extent to which the number of sessions did indeed meet the respondents' expectations was covered by the second question of the section (see Table 6: Q2). It produced a nearly 50/50 split with 29 (46%) viewing it as too little and 34 (54%) as too much. The clustering of responses, as indicated by the mean (x = 2.51) and standard deviation (σ = 0.801), shows that this component was fairly well balanced.

The second theme covered in the section primarily dealt with the focus and usefulness of supervision received. It also included the functions covered in supervision during the preceding 12 months. It was indicated, in this regard, that supervision had three core functions, viz. an administrative function (i.e. to ensure that supervisees' implement an organisation's policies and procedures correctly, effectively and appropriately), a supportive function (i.e. to improve supervisees' morale and job satisfaction) and an educational function (i.e. improve supervisees' skills and capacities) (DSD & SACSSP, 2012; Engelbrecht, 2010; Mbau, 2005; Pullen-Sansfacon, 2014). Their responses to this and the other two related questions are summarised in Table 7.

Table 7 indicates that supervision sessions were dominated by administrative matters with supportive and educational supervision combined making up a total of only 50.5%. This is a somewhat unusual finding as it is generally expected that the time spent proportionately on the three functions should be in balance, especially where beginner social workers are involved (DSD & SACSSP, 2012; Mbau, 2005; Social Workers Registration Board, 2009).

In order to clarify issues that may arise from question 3, it was followed up by two others that specifically dealt with the usefulness of the supervision that these child protection social workers received and their satisfaction with their supervision (see Table 7: Q4, Q5). In this regard, nearly a quarter (15/23.8%) found it less than useful and 16/25.4% expressed some level of dissatisfaction. This should be viewed as significant as it suggests that there are some deficiencies in the current system. The cross-referencing of responses indicated that an over-reliance on administrative supervision could have been the primary causal factor.

Thirdly, the section focused on the supervisor. It covered two factors, namely whether their supervisors were qualified for their task and whether they prepared sufficiently for supervision sessions. These two were selected for inclusion in the survey as they are often singled out as contributing to ineffective supervision in practice (Bell, 2010; Mak, 2013; Parente, 2011).

Question 6 elicited a very positive response with 52 (82.5%) of the respondents indicating that their supervisors were well or extremely well qualified for their task. This implies that any deficiency identified through the research could not be attributed (solely) to a supervisor's ability to perform his/her task.

Another factor that would have had a negative influence is how well supervisors prepared for their task. In this regard, the responses of 22 (34.8%) of the participants were that their supervisors "Never" or only "Occasionally" prepared for supervision, and another 8 (12.7%) that this happened frequently but not usually (see Table 8: Q7). This implies that nearly half of the supervision sessions were probably of an unplanned or ad hoc nature.

The types of supervision that were used

The next section of the survey was intended to profile the types or format of supervision that the respondents took part in. In this regard, the demarcation provided by Du Plooy (2011) and Silence (2017) were used as a basis to structure the responses (see Table 9).

The relatively high standard deviations (σ) in the responses to the question indicate that the types or forms of supervision used differed markedly between respondents. This could be expected, since less experienced social workers would normally require more individual supervision, whereas experienced practitioners would often benefit more from group training (Cleak & Smith, 2012; Ross & Ncube, 2018). What, however, stood out strongly was the abundant use of informal individual supervision and a relative lack of formally scheduled sessions (see Table 9: I2, I1). In this regard, nearly two thirds of the respondents indicated that informal supervision was either "Usually/Always" (13/20.6%) or Periodically (27/42.9%) used and that formal sessions were used less than 38% of the time. This would, to some extent, substantiate the conclusion drawn from Table 8 that supervision tended to be of an ad hoc nature.

Table 9 also indicates that the other forms of supervision tended to be under-utilised and that their use mainly fell into the "Seldom/Never" or "Sometimes" categories. This included group training (40/63.5%), peer supervision that was formally organised by the supervisor (44/69.8%), and peer supervision self-organised amongst supervisees (48/76.2%) (see Table 9: I4, I5, I6).

The non-individual type of supervision that seemed to dominate was group supervision, usually in the form of sectional meetings. These were either periodically (32/50.8%) or usually/always (14/22.2%) used (see Table 9: I3). It should be noted that this type of supervision is not well suited to address the educational needs of individual child protection workers.

The administration of supervision services

The next section of the survey questionnaire involved a Likert-type scale that contained seven questions. It was aimed at measuring different facets of the management of supervision at the selected service points. These facets or dimensions included the use of contracts and agendas, as well as the accessibility of supervisors in urgent cases.

The scale produced an overall mean  of 2.8 and standard deviation (σ) of 0.72, as well as a Cronbach alpha coefficient (α) of 0,869. The latter places it in the very reliable category. The results obtained with the use of the scale are summarised in Table 10.

of 2.8 and standard deviation (σ) of 0.72, as well as a Cronbach alpha coefficient (α) of 0,869. The latter places it in the very reliable category. The results obtained with the use of the scale are summarised in Table 10.

The results produced by the scale are indicative of a well-structured, albeit somewhat rigid, supervision system. Some indication of this can be found in the response to item 7, where less than a third (18/28.6%) of supervisors were usually or always available in urgent cases and 7 (11.1%) were never/seldom available, implying that the supervisees would then have to wait for a prearranged session (see Table 10:I7). Supervision also seemed to be supervisor driven, as sessions tended to be based on the needs expressed by supervisors (49/77,8%) rather than those of supervisees (37/58,7%) (see Table 10:I4, I3). The prevalence of cancelled sessions (28,6%) (see Table 10: I6) is also somewhat high.

It would seem that the strengths of the administration of the system lie in the use of contracts between supervisors and supervisees (50/79,4%) and of pre-determined agendas (43/68,2%) (see Table 10:I1, I2). The latter response, however, also indicates that the sessions were of an ad hoc nature at least 31,7% of the time.

General nature of supervision received

The sixth section of the survey specifically dealt with the nature of the supervision that the respondents received. It was primarily based on the scales developed by Crisp and Cooper (2008) and Parente (2011), but additionally also included components of the Social Work Accreditation and Advisory Board (2017). Supervisor Competency Assessment Form and core themes covered in the previous section of the survey.

Although this was basically a new scale, it proved to be remarkably reliable with a Cronbach alpha coefficient (α) of 0,981. The data generated by it are shown in Table 11.

The scale specifically focused on the relationship between the supervisor and supervisee in the preceding 12 months (Items 1 - 2, 5 - 9), as well as the respondent's perceptions of their supervisors' attributes and competencies (Items 3 - 4, 10 - 13). The comparatively high mean generated by the survey  = 2.9) implies that the supervisors predominantly behaved in an appropriate manner. As a result, only their relative strengths and weaknesses will be covered next. In this regard, the mean of

= 2.9) implies that the supervisors predominantly behaved in an appropriate manner. As a result, only their relative strengths and weaknesses will be covered next. In this regard, the mean of  = 2.9 will be used as a demarcation mechanism. It should be noted that three (see Table 11: I2, I9, I12) of the 13 items had this mean and will not be covered.

= 2.9 will be used as a demarcation mechanism. It should be noted that three (see Table 11: I2, I9, I12) of the 13 items had this mean and will not be covered.

In terms of the relationship component of the scale, only one item fell markedly below the demarcation point and could, therefore, be viewed as a relative weakness. This was their ability to function as role models  = 2,75) (see Table 11: I4). Their strong points were a positive attitude towards supervision, the ability to give appropriate advice and guidance, and to make supervisees comfortable to discuss work-related matters (see Table 11: I5, I1, I8).

= 2,75) (see Table 11: I4). Their strong points were a positive attitude towards supervision, the ability to give appropriate advice and guidance, and to make supervisees comfortable to discuss work-related matters (see Table 11: I5, I1, I8).

The supervisors' attributes tended to measure lower with four items below  = 2.9. These were to teach respondents social work

= 2.9. These were to teach respondents social work  = 2,85) and therapeutic skills

= 2,85) and therapeutic skills  = 2,74), to enhance their knowledge of social work practice

= 2,74), to enhance their knowledge of social work practice  = 2,89) and to encourage them to learn new "things" from him/her

= 2,89) and to encourage them to learn new "things" from him/her  = 2,81) (see Table 11: I4, I10, I11, I7). No item was markedly above the demarcation point.

= 2,81) (see Table 11: I4, I10, I11, I7). No item was markedly above the demarcation point.

If the responses to the scale are taken as a whole, it would seem that the supervisors had good relationships with their supervisees and were especially good at their task of providing administrative, and to a large extent also supportive, types of supervision. Most of the items that could be viewed as of an educational in nature, however, tended to measure somewhat lower. This indicates that current educational supervision is insufficient and should receive more attention in future.

The very large standard deviation (σ) of some of the items indicate that there were marked differences in the way in which respondents experienced their supervision. One of the items (see Table 11: I6) that stood out in this regard was the extent to which (some) supervisors allocated time to supervision (σ = 1,122). In this regard, 25/39,7% of the respondents indicated that it was insufficient. Although this did not seem to negatively influence the supervisor-supervisee relationships and is probably due to work pressures, it could have contributed to the relative lack of attention to educational supervision, which tends to be time consuming.

Nature of the educational supervision received

The final section of the survey questionnaire was specifically designed to profile the educational aspects of supervision on which supervisors focused during the preceding 12 months. It was primarily based on a successful sociometric scale developed by Parente (2011), but which had to be indigenised to better fit South African circumstances. The statistical analysis of the data produced in the survey showed that the adapted scale had a Cronbach alpha coefficient of α = 0,978. This high reliability coefficient, together with the good face validity indicated by the panel of experts, implies that it did meet the purpose for which it was intended.

The scale basically covered the best practice techniques that could be used in educational supervision (Parente, 2011). These included encouraging supervisees to master specific traits, empowering them to make their own decisions and providing them with appropriate opportunities and examples. Details of the data generated by the scale are contained in Table 12.

The overall mean of x =2,59 for the scale indicates that the use of the identified techniques predominantly fell within the "Periodically" category. This could be seen as somewhat of a confirmation of the under-utilisation of educational supervision by supervisors as identified via the previous scale.

The five techniques most often used by supervisors were:

• to review the supervisees' reports in order to help them improve their quality and completeness (I2: x =2,97);

• to empower them to make their own decisions regarding the cases/clients they were handling (I3: x =2,87);

• to encourage them to have their own ideas about cases (I8: x =2,76);

• to help them do a better job when they were struggling, rather than to take over the case (I10: x =2,77); and

• to notice when they had become better at doing something (I12: x =2,71).

A striking feature of the five most often used techniques, coupled with the others that were used more frequently, were that they tended to be case- and administration-focused. This included enabling them to improve their ability to deal with specific client systems and to improve their report-writing skills.

The response to Item 12, which involved noticing when respondents had become better at doing "something", has a strong supportive supervision dimension.

The five lowest ranking techniques were:

• to use roleplays to help supervisees practice new skills (I13:

= 2,16);

• to arranged for workers to share what they have learned during training/ a workshop/ a meeting/ etc. with the rest of the team (I4:

= 2,25);

• to provide examples when teaching a skill (I14: x = 2,38);

• to challenge respondents when they had unreasonable expectations of clients

= 2,38); and

• to provide opportunities for them to try "new things" (I15:

= 2,48).

A trend that emerged from the scale was that core training techniques, such as the use of role plays, examples and previous training, were somewhat neglected. The focus seemed to be on teaching supervisees to deal with issues at hand, and not to see supervision as a broader learning opportunity.

MAIN CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The first and somewhat unexpected outcome of the research was that the scales that were developed for the study proved to be very reliable and also had a high face validity within the South African context. This implies that the "The need for social work supervision" scale (α = 0.848), "The administration of supervision services" scale (α = 0.869), the "General nature of the supervision received" scale (α =0,981) and the "Nature of the educational supervision received" scale (α = 0,978) could be used in similar types of local quantitative supervision research. They should, however, also be tested within non-government settings and then subjected to statistical power analysis in order to ascertain whether the same reliability levels would be maintained in diversified contexts. It is also not yet clear whether they would be able to measure change over time.

The overall impression created by the study was that most respondents saw supervision in a positive light and had very high expectations of their supervisors. This suggests that the supervisor has many roles to fulfil and that a well-developed supervision system needs to be in place.

The responses to the survey indicated that the current system has a number of strengths and weaknesses. Its primary strength lies in the fact that it is well structured, albeit somewhat rigid. It is generally characterised by the use of contracts between supervisors and supervisees, as well agendas in pre-planned sessions. Supervisors are well qualified for their task, predominantly behave in an appropriate manner, maintain good relationships with their supervisees, and organised an appropriated number of supervision sessions per annum. They were generally good at the provision of administrative supervision, had the ability to give appropriate advice and guidance, and made supervisees comfortable about discussing work-related matters.

The research also brought several weaknesses to the fore that should be addressed by the selected provincial Department of Social Development.

Supervisees did not seem to be au fait with supervision theory and did not receive substantial in-service training to address this and other deficiencies. The majority were also not provided with the organisation's supervision policy document and/or were not familiar with its contents.

The rigidity of the system is characterised by the fact that it tended to be supervisor-driven with little input from supervisees and that it predominantly focused on administrative matters. Supportive and educational supervision sessions combined made up only half of the time spent. These trends evidently produced some level of dissatisfaction among supervisees and need to be dealt with by the employer in order to avoid contributing to burnout amongst especially newly qualified social workers (Hirst, 2019). It would seem that the system is geared towards teaching supervisees to deal with issues at hand, and not to see supervision as a broader learning opportunity.

The research also revealed several other deficiencies that need to be addressed. These include comparatively high numbers of cancelled sessions, an overreliance on ad hoc and informal sessions, the apparent overuse of group supervision which is not designed to address the individual needs of the supervisee, the allocation of insufficient time to supervision sessions and sometimes the unavailability of supervisors for urgent matters.

One of the core findings of the study was that educational supervision is under-utilised in the system. It revealed that the majority of the respondents received supervision based on their daily work activities, and that is aimed at improving their ability to deal with specific client systems and to improve their report-writing skills. It is not actually geared towards empowering child protection social workers with the additional knowledge and skills required to serve individuals, families, organisations and communities even more effectively. This implies that educational supervision should receive more attention in future.

Although these implications especially apply to the selected provincial department, they may in all probability also be true for other South African social work settings. Further research in this regard is consequently essential.

REFERENCES

BELL, L. 2010. Child welfare professionals' experience of supervision: A study of the supervision experiences of professionals who attended BASPCAN's 2009 National Congress. [Online] Available: http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Lorna-Bell/637466604 [Accessed: 17/04/2017]. [ Links ]

CLEAK, H. & SMITH, D. 2012. Student satisfaction with models of field placement supervision. Australian Social Work, 65(2): 243-258. [ Links ]

COUNCIL ON HIGHER EDUCATION (CHE). 2015. Bachelor of Social Work: Standards statement. Pretoria: CHE. [ Links ]

CRISP, B. R. & COOPER, L. 2008. The content of supervision scale. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 17(1-2): 201-211. [ Links ]

DELPORT, C. S. L. & ROESTENBURG, W. J. H. 2011. Quantitative data collection methods: Questionnaires, checklists, structured observation and structured interview schedules. In: DE VOS, A. S., STRYDOM H., FOUCHÉ, C. B. & DELPORT, C. S. L. (eds.). Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions 4th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD) & SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL FOR SOCIAL SERVICE PROFESSIONS (SACSSP). 2012. Supervision framework for the social work profession in South Africa. [Online] Available: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/documents/#policies [Accessed: 13/05/2017]. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD). 2010. Norms, standards and practice guidelines for the Children's Act. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD). 2012. Supervision framework for social work profession. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD). 2020. Annual report, 2019. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DU PLOOY, A. A. 2011. The functions of social work supervision in the Department of Health and Social Development, Ekurhuleni Region. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

DUMONT, K. & SUMBULU, A. 2010. Social work research and evaluation. In: NICHOLAS, L., RAUTENBACH, J. & MAINSTRY, M (eds.). Introduction to social work. Claremont: Juta & Company. [ Links ]

ELLIS, S. M. & STEYN, H. S. 2003. Practical significance (effect sizes) versus or in combination with statistical significance (p-values). Management Dynamics, 12(4): 51-53. [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT, L. K. 2010. Yesterday, today and tomorrow: Is social work supervision in South Africa keeping up? Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 46(3): 324-340. [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT, L. K. 2013. Social work supervision policies and frameworks: Playing notes or making music? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(4): 456-468. [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT, L. K. 2014. Fundamental aspects of supervision. In: ENGELBRECHT, L. K. (ed.). Management and supervision of social workers: Issues and challenges within a social development paradigm. Andover (UK): Cengage Learning EMEA. [ Links ]

FIELD, A. 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GLEN, S. 2016. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy. [Online] Available: https://www.statisticshowto.com/kaiser-meyer-olkin/ [Accessed: 17/05/2020]. [ Links ]

GODDEN, J. 2012. BASW/CoSW England research on supervision in social work, with particular reference to supervision practice in multi- disciplinary teams. [Online] Available: https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_13955-1_0.pdf [Accessed: 01/07/2020]. [ Links ]

GRAVETTER, F. J. & FORZANO, L. B. 2003. Research methods for the behavioral sciences. Belmont: Wadsworth/Thompson. [ Links ]

HIRST, V. 2019. Burnout in social work: The supervisor's role. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 31(3): 122-126. [ Links ]

JACKSON, S. L. 2003. Research methods and statistics: A critical thinking approach. Belmont: Wadsworth/Thompson. [ Links ]

LAVRAKAS, P. J. 2008. Cross-sectional survey design. In: LAVRAKAS, P.J. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

MAK, M. A. 2013. Supervision training needs: Perspectives of social work supervisees. Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers. Paper 225. [Online] Available: http://sophia.stkate.edu/mswpapers/225 [Accessed: 11/05/2017]. [ Links ]

MBAU, M. F. 2005. The educational function of social work supervision in the Department of Health and Welfare in the Vhembe District of the Limpopo Province. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS. 2012. Standards for social work practice in child welfare. Washington: NASW. [ Links ]

PARENTE. M. 2011. Experience of supervision scale: The development of an instrument to measure child welfare workers' experience of supervisory behaviors. [Online] Available: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2430 [Accessed: 19/05/2017]. [ Links ]

PULLEN-SANSFACON, A. 2014. Ethics and virtues in management and supervision. In: Engelbrecht, L.K. (ed.). Management and supervision of social workers: Issues and challenges within a social development paradigm. Andover (UK): Cengage Learning EMEA. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (RSA). 2005. Children's Act 38 of 2005. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944 (19 June 2006). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

ROSS, E. & NCUBE, M. 2018. Student social workers' experiences of supervision. The Indian Journal of Social Work, 79(1): 31-51. [ Links ]

RUBIN, A. & BABBIE, E. R. 2007. Essential research methods for social work. Belmont: Thomas Thompson Brooks. [ Links ]

SILENCE, E. 2017. The significance of social work supervision in the Department of Health, Western Cape: Social workers' experiences. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

SOCIAL WORK ACCREDITATION AND ADVISORY BOARD. 2017. Social work supervision guidelines. Singapore: SWAAB. [ Links ]

SOCIAL WORK DEGREE GUIDE. 2017. What is a Child Protection Social Worker? [Online] Available: http://www.socialworkdegreeguide.com/what-is-a-child-protection-social-worker/ [Accessed: 01/09/2017]. [ Links ]

SOCIAL WORKERS REGISTRATION BOARD. 2009. Guidelines for social work supervision. [Online] Available: https://www.swrb.org.hk/en/index.asp [Accessed: 03/05/2017]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL FOR SOCIAL SERVICE PROFESSIONS (SACSSP). 2007. Policy guidelines for course of conduct, code of ethics and the rules for social workers. Pretoria: SACSSP. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN QUALIFICATION AUTHORITY. 2003. Qualification: Bachelor of Social Work. Government Gazette, Vol 452, No. 24362 (7 February 2003). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN SOCIAL SECURITY AGENCY (SASSA). 2020. 2019/20 Annual report. [Online] Available: https://www.sassa.gov.za/Pages/Annual-Reports.aspx [Accessed: 01/02/2021]. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOLUTIONS. 2020. Cronbach's Alpha. [Online] Available: https://www.statisticssolutions.com/cronbachs-alpha [Accessed: 01/02/2020]. [ Links ]

UCLA INSTITUTE FOR DIGITAL RESEARCH & EDUCATION. 2019. What does Cronbach's alpha mean? [Online] Available: https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/spss/faq/what-does-cronbachs-alpha-mean/ [Accessed: 17/03/2020]. [ Links ]