Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.56 n.4 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/56-4-881

ARTICLES

The current landscape of child protection services in South Africa: a systematic review

Marianne StrydomI; Ulene SchillerII; Julie OrmeIII

IDepartment of Social Work, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6705-9854; mstrydom@sun.ac.za

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7272-9082; uschiller@ufh.ac.za

IIIPostdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Social Work, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7477-8400; jorme@ufh.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Child protection services are seen as the largest field of social work service delivery in South Africa. Repeated warnings of the 'crisis state' of child protection services have gone unheeded. The aim of this article is to determine the current landscape of child protection service delivery and research within the South African context. The developmental social welfare approach was used as the epistemological framework for this systematic review. Findings indicated a significant emphasis on statutory services and a lack of resources for family preservation efforts. Appropriate costing models should be generated to specify critical needs and garner support from stakeholders.

Keywords: challenges, child protection, child protection services, child protection systems, service delivery, social workers,

INTRODUCTION

Childhood violence and neglect are issues of serious concern that are frequently overlooked because, unfortunately, the hard facts and realities of life for vulnerable children have become far too commonplace. Around the world approximately three out of four children between the ages of 2 and 4 (300 million in total) are violently disciplined by caregivers regularly. Another 15 million adolescent girls, ages 15-19, have been sexually assaulted (UNICEF, 2017).

The statistics on violence against children in South Africa are just as staggering and demonstrate the need for an urgent response from the government, non-profit organisations, higher educational institutions and specifically the child protection system. According to the reputable Optimus Study, one in four children experiences some form of maltreatment (physical, sexual, emotional or neglect) during their childhood (Artz, Burton, Ward, Leoschut, Phyfer, Loyd & Le Mottee, 2016). Alarmingly, the study reports one in three children experiences some type of sexual abuse before reaching age 18 (Artz et al., 2016). The child homicide rate at 5.5 children per 100,000 child deaths in South Africa is twice as high as the global estimate and almost half of these homicides involved previous abuse (Mathews, Abrahams, Jewkes, Martin, & Lombard, 2013). While high rates of violence against children are considered "a daily reality" in South Africa (UNICEF, 2017a), efforts to combat violence in our homes, schools and communities demand critical analysis and immediate interventions. Child maltreatment impedes the nation's ability to uphold its commitment to children's rights and to ensure healthy socioeconomic development within the country.

Taking these realities into consideration, this paper seeks to unveil the current landscape of child protection services and research that was conducted by reviewing research that has been published in the past ten years and peer reviewed within this domain of practice.

CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEMS

Child protection systems have been defined as "certain formal and informal structures, functions and capacities that have been assembled to prevent and respond to violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation of children" (UNICEF, UNHCR, Save The Children, & World Vision, 2012: 3). There are different typologies of child protection systems around the world and varying approaches to ensuring the safety of children. Some possible typologies have been outlined as the following: punitive, moral instruction/rescue, welfare, communal harmony, child protection, family support, and rights-based child focused orientation (UNICEF et al., 2012: 6-7).

A punitive approach focuses on protecting the larger society from children who are viewed as potential risks to others. The moral instruction/rescue typology emphasizes the need to save children who are at risk of moral corruption as a result of poor parental care. The welfare typology views systemic deprivation of children through inadequate structures and policies contributing to the overall wellbeing or distress of children. The communal harmony approach prioritises communal and social harmony when children suffer maltreatment and focuses on maintaining relations within the family and community. The child protection typology uses legislation and statutory pressure to shield children from maltreatment. A family support approach to child protection aims to support families using harm-reduction interventions. The rights-based child-focused orientation emphasizes the rights of the individual child to protection and aims to help others in protecting the child's rights.

South Africa's legislation and policy on child protection focuses on a welfare typology that addresses poverty and aims to redress the injustices propagated by the punitive welfare system in place during the apartheid years affecting the majority (Taylor & Triegaardt, 2018). With a history of colonialism and subjugation for the majority of South Africans during apartheid, a new approach to welfare was constructed after the apartheid era (Patel, 2015). Undergirded by tenets from the theory of social development, developmental social welfare (DSW) was promoted as the ideal strategy for obtaining social justice for the masses (Taylor & Triegaardt, 2018). Developmental social welfare has been described as a welfare system comprised of the following themes: "a rights-based approach, social and economic development, democracy and participation, a pluralist approach, and bridging the micro and macro divide" (Taylor & Triegaardt, 2018: 66).

However, in terms of child protection service delivery, South Africa often follows a child protection typology that focuses strongly on legislation and statutory pressure to shield children from maltreatment.

CHILD PROTECTION SERVICES IN SOUTH AFRICA

In post-apartheid South Africa the child protection system has experienced shifting transformations with the introduction of new policies and attempts to adapt a Western model of intervention (Schmid, 2012). The White Paper for Social Welfare of 1997 presented a paradigm shift for the nation which aimed at addressing the numerous societal inequities created by the system of apartheid. The document delineated a developmental social welfare (DSW) approach which was presented to ensure service delivery to previously marginalised groups. The integrated service delivery model (ISDM) was developed to ensure the implementation of the White Paper of 1997 and the DSW approach (Department of Social Development, 2006). In line with the DSW approach, the ISDM identified the levels of service delivery emphasising that services should focus on prevention services, early intervention services, statutory services as well as re-integration and aftercare services. However, the implementation of the DSW approach has been criticised by scholars and practitioners alike, as a high demand for casework-oriented services with limited available resources constrains a focus on prevention efforts and developmental interventions (Lombard, 2008; Schmid, 2012). Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that social workers are currently experiencing far too many challenges to enable them to focus more on preventative interventions and thus the paradigm shift towards a developmental approach has not been realised (Ndonga, 2014; Strydom 2010; Van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016).

To address some of the historical challenges experienced during the apartheid regime and under the previous South Africa, Child Care Act (74 of 1983), where the focus of services was more residual and institutional than following a DSW approach, the new Children's Act (Act 38 of 2005 as amended) was adopted to enhance measures to protect all children in South Africa from abuse and neglect (Republic of South Africa, 2005). Considered as a landmark piece of legislation, the Children's Act lays the groundwork for enhancing child protection measures and combating violence against children, including increasing support of government entities. It is the task of the Department of Social Development (DSD) to address all levels of services that include prevention, early intervention, statutory and aftercare services in child welfare (Van Niekerk & Matthais, 2019). Subsidised by the Department of Social Development, non-profit organisations collaborate with the government to provide statutory services around the country.

However, these non-profit organisations (NGOs) are under-resourced and overwhelmed because of a high prevalence of child abuse and neglect in the country (Van Niekerk & Matthias, 2019). Schmid (2012) identified several trends in child welfare in South Africa in the years 2000 to 2010 that indicated an overburdened NGO system. Following a qualitative research study, some of the themes that emerged from the data related to the development of an integrated approach and include: "balance between community and case work, tensions between therapeutic and administrative case work tasks, expert versus user-led programmes, early intervention and prevention, and inter-sectoral collaboration versus substitution of services" (Schmid, 2012: 20-21). Schmid also identified some of the factors contributing to the child welfare crisis such as workforce challenges, issues around collection of information, and funding constraints. In the study interviewees expressed the need for a "child welfare information management system" and coordination between practitioners, academics, legislators, governing bodies and society as a whole. Without this management system, critical planning and development in child welfare are obstructed (Schmid, 2012).

Although some progress has been made since Schmid's study, which was completed in 2010, the field of child protection continues to experience the same challenges as noted ten years ago. Van Niekerk and Matthias (2019: 250) point out that "there are many gaps in the coordination and integration of services that contribute to inequalities in service delivery to children, families and communities. The child protection system lacks a clear overarching structure of implementation and integration between directorates within the DSD, levels of government, and sectors involved in the provision of CPS." They also recommend that an all-encompassing strategy for CPS be implemented across non-profit and government sectors to enhance coordination and service delivery. Additionally, child protection services nationwide are inadequately funded, especially among non-profit organisations. The inadequate funding results in an inability to address structural constraints, such as the lack of human capital and resources, lack of basic organisational resources such as vehicles or fuel to do home visits, and overbearingly high caseloads (Schiller, 2017; Strydom, 2010; Strydom, Spolander, Engelbrecht & Martin, 2017). The combination of these constraints has produced the strong emphasis on statutory services and crisis intervention (Ndonga, 2014; Strydom, 2010; Van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016).

Focusing on aftercare services, a longitudinal quasi-experimental study conducted in 2016 examined the efficacy of a therapeutic programme for sexually abused children using mixed methods. Using intervention and control groups, 77 children and 77 caregivers were interviewed for the study at five different locations (Mathews, Berry & Marco-Felton, 2017). Although many of the research participants described an improvement in their wellbeing while in the programme, there were also glaring inadequacies in the support they received. There were no significant changes in post-traumatic and depressive symptoms after intervention. The research findings revealed that children were continuously exposed to risk and had experienced multiple traumas. Moreover, the response to trauma from social service personnel was inadequate as they received poor supervision and exhibited poor case management, especially in the development of child protection plans. This indicates that the statutory response and aftercare services do not necessary lead to successful re-integration. A stronger focus on prevention and early intervention services would be more beneficial for families in the child protection system.

In a child protection policy brief Jamieson, Sambu and Mathews (2017) suggest that the results of the above study demonstrate "how the child protection system is failing to protect children in practice. Practitioners fail to identify children at risk and they manage cases poorly, few children and families have access to therapeutic care and support to combat complex trauma, and the different professions don't work together." The Children's Act 38 of 2005 is a strong piece of legislation that has been ineffectively implemented (Jamieson, Sambu & Mathews, 2017). To enhance the child protection system of South Africa, the authors offer the following recommendations: strengthen early identification and prevention services, enhance assessment of abuse and neglect, ensure safe environments for children, improve treatment and intervention responses and develop intersectoral collaboration through the use of multidisciplinary teams. Once again it is evident that many of these recommendations were highlighted by scholars more than ten years ago (Lombard, 2008, Schmid, 2012; Strydom, 2010).

These changes should be driven by the government. September (2006: S66) postulated that the government of South Africa has demonstrated "policy-level commitment" to enhance the well-being of children and protect them from harm, but the implementation of these policies remains insufficient. The lack of policy implementation has consequences for families, as they are subsequently denied access to preventative family support services to prevent the unnecessary removal of children. Families that are involved in child protection services are often experiencing numerous challenges, such as poverty, low levels of education, unemployment, financial stress, substance abuse and family violence. These challenges are confirmed by social workers as obstacles experienced in service delivery to prevent the removal of children and preserve families (Ndonga, 2014; Strydom, 2010). Most of the types of social issues experienced by families necessitate a combination of continuous prevention and early intervention services to preserve family life, such as educational, therapeutic and concrete services (Strydom, 2012).

In the light of the fact that research results consistently identify the same challenges in the child protection system, the researchers decided to do a systematic review to determine the current landscape of child protection services delivery and research in South Africa to determine gaps to be addressed. The main research objectives were to explore the following questions:

• What is the content and methods of research conducted within the field of child protection?

• What are the levels of service delivery within the child protection system?

• What are the realities that social workers are facing when conducting child protection services?

• What are the challenges the families are experiencing within the child protection system?

METHODOLOGY

This systematic review explored the current policies, trends, programming and assessment practices in child protection services. To complete the systematic review the following guidelines were implemented: the research question was defined, the search methods were identified and used to retrieve data, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were set, and the results were reported (Crisp, 2015). Searches were conducted during November and December 2019 in the Ebscohost Discovery database and the Sabinet database to ensure data saturation, covering both international and national literature. EbscoHost Discovery accesses multiple databases including: Academic Search Complete, APA PsychInfo, BASE, Complementary Index, Directory of Open Access Journals, PubMed, SocINDEX with Full Text, Science Direct, Social Sciences Citation Index and Supplemental Index. Publications were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: journal article, relevance to the field of child protection in or related to South Africa. Magazine articles, dissertations or theses, reports and books were excluded from the review. Limiters were set to include only full text and articles available in the library collection for all searches completed.

The first literature search was conducted by searching for articles published in EbscoHost Discovery database using subject terms "child protection" and "South Africa" between the years 2010 and 2019. From 12 articles, one article was removed for duplication of the same study. Three articles were removed due to lack of relevance to the field of child protection in South Africa. After screening, this search returned eight journal articles in total.

A second search was performed using EbscoHost Discovery using the subject term "child protection" and the terms "South Africa" and "service delivery" in text. The search was limited to full text and available in library collections between 2010 and 2019. There were 13 journal articles that emerged from the search. Five of the articles were previously screened in and three of the articles were excluded due to lack of relevance to the topic of child protection in South Africa. A total of five articles was selected for analysis from this search.

Using the same limiter for time (between 2010 and 2019), a third search was performed in EbscoHost Discovery using the subject term "social worker" and the terms "challenges" and "protection" in the abstracts with "South Africa" in the text. Additional limiters were set to include full text and available in library collection. After duplicates were removed, the search returned 16 articles. One article was removed as it was a duplication of a previous study and eight were removed due to lack of relevance to child protection in South Africa. Three were articles previously screened in. Therefore, four articles were included in the analysis.

A similar search was conducted using the database Sabinet to access more of the relevant literature in South Africa. This search used the term "child protection" in abstracts from 2010-2019 to extract articles on the topic. A total of 44 publications emerged from the search. Thirty publications were excluded because they were magazines or they explored child protection in other countries. In total, 14 articles were included for analysis.

There were 30 publications that were analysed from the EbscoHost databases (Agere & Tanga, 2017; Agere, Tanga, & Kang'ethe, 2017; Ali, 2017; Couzens, 2011; Hope, & Van Wyk, 2018; Kaonga, Batavia, Philbrick, & Mechael, 2016; Malherbe, & Haefele, 2017; Mathews, 2013; Mathews, & Martin, 2016; Matthias, 2015; Nhedzi & Makofane, 2015; Okem, 2017; Patel & Hochfeld, 2011; Rosenberg, Pettifor, Myers, Phanga, Marcus, Bhushan & Mtwisha, 2017; Schiller, 2017; Schmid, 2010; Schmid, 2014; Siljeur, 2016; Spies, Delport, & Le Roux, 2017; Strode, 2015; Svevo-Cianci, Hart & Rubinson, 2010; Truter, Theron, & Fouché, 2018; Van Graan, 2012; Van Graan & Snyman, 2011; Van Huyssteen & Strydom, 2016; Van Raemdonck & Seedat-Khan, 2018; Vetfuti, Goliath & Perumal, 2019; Wallace-Henry, 2015; Ward & Bakhuis, 2010; and Warria, 2018).

Due to the limited scope of the articles yielded by the database searches, 21 additional articles were included to enhance the review (Alpaslan & Schenck, 2012; Böning & Ferreira, 2013; Botes & Ryke, 2011; Dhludhlu & Lombard, 2017; Du Toit, Van der Westhuizen & Alpaslan, 2015; Gallinetti & Sloth-Nielsen, 2010; Hope & Van Wyk, 2018a; Jordan, Patel & Hochfeld, 2014; Mbazima, 2016; Mnisi & Botha, 2016; Ngwenya & Botha, 2012; Omar & Patel, 2012; Phetlhu & Watson, 2014; Roux, Bungane & Strydom, 2010; Schiller, 2015; Sibanda & Lombard, 2015; Singh & Singh, 2014; Steyn, Van Wyk & Kitching, 2017; Strydom, 2010; Strydom, et al. 2017; Van Niekerk & Matthias, 2019).

In total, 51 journal articles were then analysed in depth. Each article was examined using a total of 12 questions and the results were entered in a Google questionnaire form. With the guiding epistemological framework of developmental social welfare, the Google questionnaire form was developed at the beginning of the study using a simple survey set up in Google Drive. After the exclusion process had been completed, information from each article was entered into the Google questionnaire form and then exported into an Excel document for further analysis. The process of inclusion and exclusion is depicted graphically in Figure 1 below.

The analysis of articles was performed using exploratory questions to ascertain the types of research studies conducted and the results obtained from the studies (see Table 1). The results of each individual analysis were entered into an online survey that saved the information entered. The analysis began with determining the year, full reference and key words of the article. Then the types and number of participants in the research studies were identified. The research method and research questions or hypotheses were also examined. Next, the location where the study was conducted was pinpointed, along with any theoretical framework used to guide the study. Then, the level of services rendered by social workers within the article was identified. Challenges with human capital and human resources within organisations were then highlighted, with human capital referring to skills or knowledge and human resources implying number of staff or personnel. If discussed, organisational constraints were entered into the survey. The different types of challenges that families within the child protection system experienced were included as well.

TRUSTWORTHINESS IN A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

It is important to illustrate trustworthiness in a systematic review by ensuring a full description of the data collection, analysis and logical use of concepts. The researchers ensured academic rigor and trustworthiness throughout the systematic review by adapting the checklist developed by Elo, Kããriãinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen, and Kyngãs, (2014) to ensure trustworthiness in qualitative content analysis in this particular study.

In the first instance, there is trustworthiness in the preparation phase (Elo et al., 2014). During this phase the main thrust is to focus on data collection, sampling strategy and suitable unit analysis. This was followed by clearly indicating the unit of analysis and categories that were used to address the formulated research questions.

The organisation phase ensured that the categories were well created and aligned to allow interpretation (Elo et al., 2014). The researchers used the DSW approach as the epistemological basis that supported the development of categories and interpretation of the data. As clearly outlined by Graneheim and Lundman (2004), it is essential to understand and acknowledge that there will always be bias by the researchers when interpreting texts. This aspect of interpretation was approached critically by ensuring a literature control and saturation of data in the review process.

In the reporting phase of the study that follows there was a particular focus on the key concepts as developed by Lincoln and Guba (1985), namely credibility, dependability, conformability, transferability and authenticity. Credibility was ensured by keeping a rigorous audit trail of all processes to identify the different research studies that were included in or excluded from this study. Dependability was corroborated since all studies that were used are traceable and this contributed to data stability. Conformability refers to objectivity, thus the congruence between two or more people about the accuracy, relevance and meaning of the data. In this study, the review of articles for inclusion and exclusion was completed by three researchers, adding to the relevance of the publications in the study. Transferability relies on the reasoning that the data can be generalised. The consolidation of all these studies provides a good platform for scholars and practitioners alike to identify the gaps and needs in both training, service delivery and policy development. Lastly, authenticity was ensured by illustrating the range of realities that were presented by all the researchers' work that was integrated into this systematic review.

DATA ANALYSIS

With the aim of obtaining a broad overview of the contents in the scholarly literature on child protection, the study carefully reviewed 51 articles. For the sake of brevity, only the most germane questions and findings were explored in depth.

The 12 questions that were used for the data analysis are presented in Table 1 below.

After all the data were captured, the findings were thematically analysed guided by the research questions and theoretical framework. A mixed methods approach was utilised to examine 51 articles on child protection. Only the quantitative results are presented and discussed in this article under specific categories and sub-categories. Qualitative findings will be shared in a forthcoming article that made use of secondary data analysis.

RESULTS

Research done in child protection field

Research that was done in the field of child protection will be presented under the sub-categories of year in which the studies were published, participants in these studies, research approaches utilised, as well as the location where the studies were conducted. This will provide us with a good overview of the current landscape of child protection research in South Africa.

Publication year

The review yielded 51 articles on child protection in South Africa.

Eleven articles on child protection in the year 2017 were examined, eight in the year 2015 and six in the year 2010. The rest of the articles were evenly dispersed throughout the other years between 2011 and 2019.

Type and number of participants

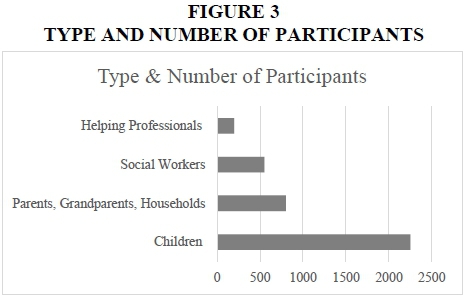

In the 51 articles analysed, there were ten articles that did not mention participants as they were either conceptual articles or policy analysis. From the remaining 41 articles analysed all participants were disaggregated by type and number. There were 550 social workers who participated in the research studies. There were 2,252 cases or child participants in the research studies. There were 801 parents, grandparents or households that participated in the research studies. Another category of participants included 199 helping professionals in the child protection system, such as child welfare instructors, directors, managers, advocates, counsellors and youth care workers. The type and number of participants are shown in Figure 3.

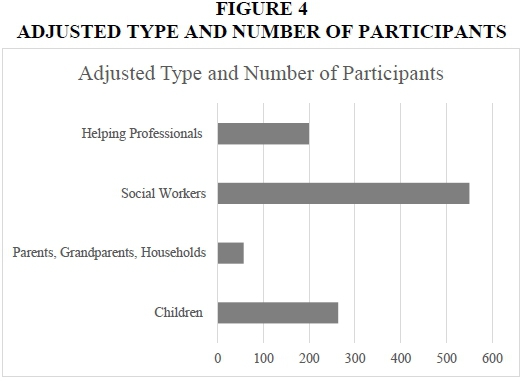

From the graph above, it seems that a large number of children were included and consulted in the research studies. However, when closely analysing the results, it should be noted that one of the studies with children was a multi-country study including 1,000 adolescent girls (Rosenberg et al., 2017). Another study reviewed 707 cases of children's deaths (Mathews & Martin, 2016). An additional study with significantly high numbers was a study conducted using several focus groups and 282 children to explore the topic of gang involvement in the Western Cape (Ward & Bakhuis, 2010). If these three studies were excluded as outliers, the total number of children in all of the studies would be significantly lower, yielding a total of 263 child participants. Similarly, within the category of parents, grandparents or households, two of the studies were conducted with 344 women (Patel & Hochfeld, 2011) and 343 households, 37 young women and 20 young mothers (Jordan, Patel, & Hochfeld, 2014), significantly increasing the number of parental participants. By excluding these two articles as outliers, the total number of parents, grandparents or households would be just 57 participants. This is graphically depicted in Figure 4 below.

The adjusted figure illustrates that the majority of the studies use social workers as participants. Prompted by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, several scholars have expounded on the need for greater participation of children as they make critical decisions about their lives when involved in the child welfare system (Cook, Blanchet-Cohen & Hart, 2004; Moyo, 2015; O'Kane, 2013; Viviers & Lombard, 2013). Schiller (2015) demonstrated in a qualitative research study the need for greater participation of adolescents in foster care during decision-making processes. In a similar vein, Strode (2015) proposes that South African legislation has become so restrictive that children's participation in research is severely limited.

Thus, important deductions are made within the child protection domain without having a representative voice of service users and practitioners in the field. This further negates the DSW approach (Patel, 2015), which should ensure participation and democracy in service delivery as well as bridging the micro-macro divide by ensuring greater access to social service delivery. This further illustrates how South Africa follows a child protection typology rather than a DSW approach. As we reflect on this finding, it is clear that as researchers we also are not including enough of our stakeholders in research studies. Participation from all stakeholders should be emphasised as, often, we steer away from including children in research because of the ethical restrictions. However, it needs to be emphasised that participation from these stakeholders, especially children, is critical to allow their voices to be heard in order to address implementation issues and evaluation of policies and services.

Research approach

The research approaches followed within the articles were largely qualitative with a sum total of 28 articles as depicted in Figure 5. There were 11 policy analyses, conceptual articles or literature reviews performed followed by five mixed methods and five quantitative articles. There were two articles based on secondary data analysis.

The majority of the studies were qualitative. Undoubtedly, the cost of survey research and implementing controlled experiments may create significant barriers to this type of research. The minimal number of quantitative analyses observed in this research study is not exclusive to child protection or the field of social work. Payne (2014) states that a lack of rigorous quantitative method research is also evident in the discipline of sociology, where a series of historical events led to a greater focus on qualitative research. It should be noted that these research studies were not analysed in depth as that was not the purpose of this paper, which was rather to illustrate what the preferred research approach is in the field of child protection and possibly identify gaps for further exploration and research studies needed within this field.

Location where studies were conducted

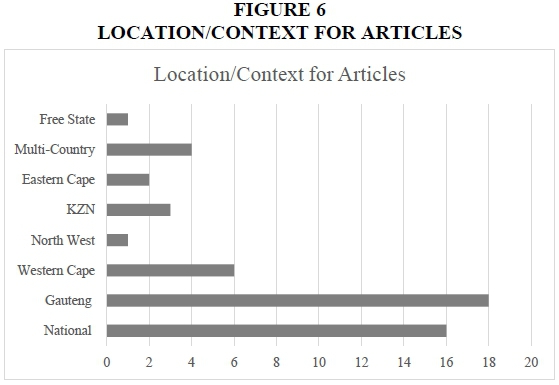

The majority of the studies was performed within the context of South Africa, as this was a qualifier included in this review; 19 articles were identified as being completed in the country with an unspecified location (see Figure 6 below). Some articles were global studies, comparative policy analysis and conceptual publications deemed relevant to the study.

The largest number of studies was conducted in the Gauteng and Western Cape provinces, which could possibly indicate the availability of more resources such as higher education institutions, research grants and generally better socio-economic circumstances. Provinces such as Limpopo, Mpumalanga and the Northern Cape were not mentioned in any single studies, but they were possibly included in the national studies. Quite a number of national studies (n=16) were noted to have contributed positively to the landscape of the current child protection services and research in the country.

Level of service delivery

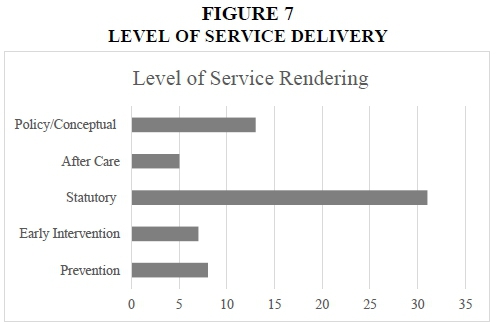

The levels of service delivery are outlined in the ISDM (Department of Social Development, 2006) as follows: prevention, early intervention, statutory and aftercare services, with a preferred focus on prevention and early intervention to implement the DSW approach (Republic of South Africa, 1997). Out of the 51 articles, 31 discussed statutory services in South Africa. There were eight articles that focused on prevention and seven articles that discussed early intervention. Five of the articles discussed aftercare services and thirteen of the articles were mainly conceptual or about policy (see Figure 7). Some of the articles depicted more than one level of service rendered and that is reflected in Figure 7 below.

Reviewing the domain of service delivery, almost 61% of the articles (n=31) focused on statutory intervention. This result draws attention to the child protection typology for child welfare that South Africa is currently following, with a strong emphasis on legislation, as opposed to the welfare typology that is endorsed by the DSW approach.

This strong emphasis on statutory services is not only related to the structural constraints experienced by the system, but also to the reality that service users involved with statutory level services are already overburdened by poor quality of life and low social functioning. Interventions at this level require longer-term resource-intensive service delivery, which in turn contributes to the administratively heavy caseloads. These heavy caseloads with a strong focus on crisis intervention combined with a lack of human capital limit the time available to develop and implement appropriate community-based preventative services, as well as early intervention services (Strydom, 2013; Strydom, 2012).

The vision of preventative services as outlined by the Framework for Social Services suggests that services should focus "on preventing development needs from developing into social challenges or risks" (Department of Social Development, 2013: 27). Payment of a Child Support Grant can be viewed as a preventative form of service delivery, with 12.5 million families receiving a grant (SASSA, 2020). Although the child support grant is negligible in terms of overall expenses, it remains a critical factor in supporting impoverished families (Patel & Hochfeld, 2011). Devoting precious time and resources to prevention efforts (e.g. parenting groups, substance abuse awareness and family preservation programmes) is viewed as an ideal and not a realistic service that can be offered in the midst of the daily crisis responses of child protection service agencies.

Social work realities and challenges in child protection

The realities that social workers are experiencing in the child protection system are divided into human capital and human resources categories as well as the different organisational constraints within which they need to function and operate.

Human capital and human resources

The literature on child protection alludes to the challenges concerning human capital and human resources that oftentimes impede child protection service delivery. Regarding the topics of human capital and human resources, 22 articles cited the high caseloads of social workers (see Figure 8 below). Fourteen of the articles referenced a lack of supervision for social workers and nine of the articles referred to working in a constant state of crisis management. There were four articles that discussed a lack of training, two articles that mentioned a high level of administrative work and two articles that referred to a lack of personnel or staff turnover.

Almost 50% of the articles cited the high caseloads of social workers. This is traced throughout the period between 2010-2019. Yet the unemployment rates of social workers, especially among new graduates, are staggering. As of July 2019, there were 12,000 unemployed social workers in the nation (Department of Social Development, 2019). This clearly shows the lack of uptake of the social workers by the Department of Social Development and non-profit organisations.

Caseloads and supervision guidelines as outlined by the Framework of Social Services (Department of Social Development, 2013: 24-25) seem to be reasonable and attainable. However, the realities of the social workers as illustrated by this study and others paint a bleak picture of the current status quo within this field of service delivery (Dhludhlu & Lombard, 2017; Nhedzi & Makofane, 2015; Sibanda & Lombard, 2015;). There also tends to be a high staff turnover in the sector and continuous working and functioning in a state of crisis (Strydom, 2012).

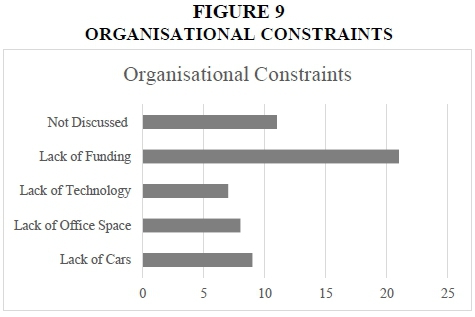

Organisational constraints

Access to resources is also a formidable organisational constraint within child welfare organisations, as indicated in Figure 9. There were 21 articles that discussed the lack of funding to support the organisation and its mission. Eleven articles did not discuss organisational constraints at all, and nine articles spoke about a lack of vehicles or transportation and how this constrained service delivery. There were eight articles that reported a lack of office space impeding service provision. Another seven articles mentioned a lack of technology such as functioning computers and fax machines that could support the delivery of timely services.

Approximately 40% of the articles (n=21) highlighted the challenge of inadequate funding within organisations. Given the current allocation of resources by the South African government, more than 90% is earmarked for social security and less than 10% is for service delivery (National Treasury, 2019; National Treasury, 2020). The issue of inadequate financial resources has been highlighted repeatedly with minimal response from governmental authorities.

Challenges experience by families in the child protection system

Regarding challenges experienced by families in South Africa, 17 of the articles spoke about financial stressors and 12 articles mentioned unemployment issues (see Figure 10). Another 12 articles discussed a general lack of resources within families and ten articles reported abuse and neglect being problematic. There were nine articles that indicated that community or family violence was a critical issue. Also, HIV/AIDS was mentioned in nine articles as a common family issue. Family structure issues, such as deceased or divorced parents, were reported in eight articles. In seven articles substance abuse was indicated as a significant family challenge. Lack of education and lack of transport were mentioned in five articles. Lack of parenting skills was discussed as being problematic in three articles. Lack of housing and lack of social network were reported in two articles respectively. There were also two articles that identified parental illness or disabilities as being problematic for families. There was just one article that focused on personality factors of children being a challenge. Additionally, there were some miscellaneous challenges that were discussed in the articles including lack of food, criminal activities, cultural issues, separation from family members, lack of child supervision, inappropriate sexual behaviour among adolescents, no telephone and normal family life stressors.

Several studies have demonstrated that children in poverty-stricken families are at greater risk of child abuse (Bower, 2003; Meinck, Cluver, Boyes & Ndhlovu, 2013; Youssef, Attia, & Kamel, 1998). The analysis of articles confirmed this correlation as the challenges for families involved in the child protection system in South Africa are predominantly related to financial wellbeing. As indicated by the number of articles, these families are overly burdened with financial constraints (n=17), unemployment challenges (n=12) and limited resources (n=12). There were also nine articles that discussed the impact of familial or community violence, supporting the established link between violence and child abuse (Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl, & Moylan, 2008; Meinck, Cluver, & Boyes, 2015). Another nine articles mentioned the burden of HIV/AIDS for families. A study conducted with 3515 South African children found that youths are more likely to experience physical abuse in AIDS-ill families (Meinck, Cluver, & Boyes, 2015). This indicates the need for proper implementation and evaluation of prevention programmes.

LIMITATIONS

This paper acknowledges that the focus of this study was on research and policy reviews from academics; further analysis needs to include practice-based reports from the Department of Social Development and agencies like UNICEF.

CONCLUSION

The types of challenges within the child protection system are not unique to the South African context, but the service delivery response is not in alignment with the systemic challenges of the country. The focus of service delivery is often more reactive than preventative. Thus, a lack of dedicated funding for preventative services constrains the delivery of these services. If there is a lack of prevention services in the communities aimed at family preservation, there will always be a critical need for statutory services.

This systematic review reveals that the practice response to child protection employs a child protection typology as indicated by the high usage of statutory services throughout the country. The implementation of the developmental social welfare approach still seems to be only an approach adopted in 'theory' that is hampered because of the lack of funding and of coordinated and integrated service delivery. There are major implementation challenges with the DSW approach. The continuous outcry of social workers is that their work circumstances warrant serious attention, given the inadequate supervision and overburdened caseloads. The realities of social workers are linked to the lack of funding and the inability of agencies to garner sufficient funding. Further analysis of current costing models and alternative approaches from diverse sectors are required to support the effective delivery of child protection services.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In light of the findings of this study and 30 cumulative years of both practice and research experience in child welfare, the researchers make the following policy, practice and academic recommendations.

Policy

• The National Treasury should allocate a greater portion of the social development budget towards provincial social development to enable sufficient social service delivery espousing the DSW approach.

• A critical review of policies should be undertaken to ensure an Africanised approach in alignment with the South African context and available resources.

Practice

• Costing models need to be developed and promulgated so that financial need is readily apparent and accessible for all relevant stakeholders. This will ensure that pleas for financial support, especially for preventative and aftercare programmes, are substantiated.

• Family preservation programmes should be developed and implemented in communities to provide preventative services as opposed to the current emphasis on statutory services.

• More training should be offered for developmental family preservation interventions, such as parenting programmes, home visits, etc.

• Volunteers, such as retired personnel and faith-based groups, should be identified and trained in communities to assist vulnerable children and families in communities.

• The efforts of all social service practitioners and related disciplines (e.g. human settlement, public health, educational and community health) should be aligned to develop and implement preventative services to children and families in communities.

Education

• Educate students and social workers to develop entrepreneurial social enterprises within family preservation practice, such as parenting programmes, financial planning and management. These can serve as community-based resources for all community members and stakeholders.

• Both qualitative and quantitative research skills should form part of the research curriculum.

Research

• Researchers should make greater efforts to include children in their research by completing ethics applications. This will honour children's right to participation and allow their voices to be heard regarding implementation and evaluation of policies.

• Families involved with the child protection system should be sought after for their experiential knowledge and included in future research studies.

• Future research studies should undertake a comparison of the differential disbursement of resources among social service agencies and the outcomes of service delivery.

• Researchers should perform larger quantitative analyses and undertake mixed methods studies on child protection to validate recurring issues.

The current state of the child protection system calls for bold action in policy and practice to alter normative 'crisis' responses to preventative empowerment strategies. To create lasting change in South African communities, further analysis of current costing models and innovative alternative approaches from diverse sectors are required.

REFERENCES

AGERE, L.M., & TANGA, P. T. 2017. A critical examination of the nexus between psychosocial challenges and resilience of child headed households: a case of Zola, Soweto. Child Abuse Research in South Africa,18(2):59-67. [ Links ]

AGERE, L. M., TANGA, P. T., & KANG'ETHE, S. 2017. Hurdles impeding the provision of holistic services to children in need of care and protection: a study of selected child and youth care centres in Soweto, South Africa. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 18(2):77-84. [ Links ]

ALI, M. I. 2017. The legislative developments in the criminal justice system of South Africa addressing child sexual abuse: lessons for other developing countries. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 18(1):97-107. [ Links ]

ALPASLAN, N. & SCHENCK, R. 2012. Challenges related to working conditions experienced by social workers practising in rural areas. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(4):400-418. [ Links ]

ARTZ, L., BURTON, P., WARD, C.L., LEOSCHUT, L., PHYFER, J., LOYD, S. & LE MOTTEE, C. 2016. Optimus study South Africa: Technical report sexual victimisation of children in South Africa. Zurich: UBS Optimus Foundation. [ Links ]

BÖNING, A. & FERREIRA, S. 2013. An analysis of, and different approach to, challenges in foster care practice in South Africa. Social work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(4):519-543 [ Links ]

BOTES, W. & RYKE, E. 2011. The competency base of social workers with regard to attachment theory in foster care supervision: A pilot study. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 47(1):31-50 [ Links ]

BOWER, C. 2003. The relationship between child abuse and poverty. Agenda, 17(56):84-87. [ Links ]

COOK, P., BLANCHET-COHEN, N. & HART, S.N. 2004. Children as partners: Child participation promoting social change: Prepared for The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) Child Protection Unit. International Institute for Child Rights and Development. [ Links ]

COUZENS, M. 2011. Child-friendly municipalities: Including children on local government's agenda. Stellenbosch Law Review/Stellenbosch Regstydskrif, 22(1):137-159. [ Links ]

CRISP, B.R. 2015. Systematic reviews: A social work perspective. Australian Social Work, 68(3): 284-295. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2006. Integrated Service Delivery Model for Developmental Social Services. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. Framework for Social Service Delivery. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2019. Minister Lindiwe Zulu on plight of unemployed social workers. [Online] Available: https://www.gov.za/speeches/unemployed-social-workers-17-jul-2019-0000 [Accessed: 20/02/2020]. [ Links ]

DHLUDHLU, S.& LOMBARD, A. 2017. Challenges of statutory social workers in linking foster care services with socio-economic development programmes. Social Work, 53(2):165-185. [ Links ]

DU TOIT, W., VAN DER WESTHUIZEN, M. & ALPASLAN, N. 2016. Operationalising cluster foster care schemes as an alternative form of care. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(3):391-413. [ Links ]

ELO, S., KÀÀRIÀINEN, M., KANSTE, O., PÖLKKI, T., UTRIAINEN, K. & KYNGÀS, H. 2014. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE OPEN, 4(1):1-10. [ Links ]

GALLINETTI, J. & SLOTH-NIELSEN, J.2010. Cluster foster care: A panacea for the care of children in the era of HIV/AIDS or an MCQ? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 46(4):486-495. [ Links ]

GRANEHEIM, U. H.& LUNDMAN, B. 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2):105-112. [ Links ]

HERRENKOHL, T.I., SOUSA, C., TAJIMA, E.A. HERRENKOHL, R.C. & MOYLAN, C.A., 2008. Intersection of child abuse and children's exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9(2):84-99. [ Links ]

HOPE, J. & VAN WYK, C., 2018. A model for emergency child protection intervention. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 19(1):45-47 [ Links ]

HOPE, J. & VAN WYK, C. 2018a. Intervention strategies used by social workers in emergency child protection. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 54(4):421-437. [ Links ]

JAMIESON, L., SAMBU, W. & MATHEWS, S. 2017. Out of harm's way? Tracking child abuse cases through the child protection system at five selected sites in South Africa-Research Report. Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

JAMIESON, L., SAMBU, W. & MATHEWS, S. 2017. Policy Brief: Strengthening the Child Protection System in South Africa. [Online] Available: https://www.saferspaces.org.za/resources/-entry/policy-brief-strengthening-the-child-protection-system-in-south-africa [Accessed: 05/09/2019]. [ Links ]

JORDAN, N., PATEL, L. & HOCHFELD, T. 2014. Early motherhood in Soweto: The nexus between the child support grant and developmental social work services. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 50(3):392-409. [ Links ]

KAONGA, N. N., BATAVIA, H., PHILBRICK, W. C. & MECHAEL, P. N. 2016. Information and communication technology for child protection case management in emergencies: an overview of the existing evidence base. Procedia engineering, 159:112-117. [ Links ]

LINCOLN, S. Y. & GUBA, E. G. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. 2008. The implementation of the White Paper for Social Welfare: A ten-year review. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 20(2):154-173. [ Links ]

MALHERBE, C. & HÃEFELE, B.W., 2017. Filicide in South Africa: a criminological assessment of violence in the family. Child abuse research in South Africa, 18(1):108-119. [ Links ]

MATHEWS, S. 2013. Social protection and the National Development Plan: Closing the gap for children-opportunities and challenges. Social Dynamic: A Journal of African Studies, 39(1):138-143. [ Links ]

MATHEWS, S., ABRAHAMS, N., JEWKES, R., MARTIN, L. J. & LOMBARD, C. 2013. The epidemiology of child homicides in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91:562-568. [ Links ]

MATHEWS, S., & MARTIN, L. J. 2016. Developing an understanding of fatal child abuse and neglect: Results from the South African child death review pilot study. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal, 106(12):1160-1163. [ Links ]

MATHEWS, S., BERRY L., & MARCO-FELTON, J. L. 2017. Outcomes assessment of the Isibindi-Childline residential therapeutic programme for sexually-abused children. Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

MATTHIAS, C. R. 2015. Parameters of confidentiality in child protection alternative dispute resolution. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, (3): 290-305. [ Links ]

MBAZIMA, M. 2016. The lived experiences of Black African mothers following the birth of a child with down syndrome: Implications for indigenisation of social work. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(2):167-187 [ Links ]

MEINCK, F., CLUVER, L., BOYES, M., & NDHLOVU, L. 2013. Risk and protective factors for physical and emotional abuse victimisation amongst vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abuse Review, 24(3):182-197. [ Links ]

MEINCK, F., CLUVER, L. D. & BOYES, M. E. 2015. Household illness, poverty and physical and emotional child abuse victimisation: Findings from South Africa's first prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 15(1):444. [ Links ]

MNISI, R. &BOTHA, P. 2016. Factors contributing to the breakdown of foster care placements: The perspectives of foster parents and adolescents. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(2):227-244. [ Links ]

MOYO, A. 2015. Child participation under South African Law: Beyond the Convention on the Rights of the Child? South African Journal on Human Rights, 31(1):173-184. [ Links ]

NDONGA, M.M. 2015. Perceptions of social workers regarding the rights of children to care and protection. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University (M thesis) [ Links ]

NGWENYA, P. & BOTHA, P. 2012. The foster care backlog: A threat to the retention of social workers?. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(2):209-224. [ Links ]

NHEDZI, F. & MAKOFANE, M. 2015. The experiences of social workers in the provision of family preservation services. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk 51(3):354-378. [ Links ]

O'KANE, C. 2013. Children's participation in the analysis, planning and design of programs. London: Save the Children. [ Links ]

OKEM, E. A. 2017. A Comparative analysis of child social protection in Brazil, Nigeria and South Africa. Loyola Journal of Social Sciences, 31(2):189-207. [ Links ]

OMAR, S. & PATEL, L. 2012. Child-on-child sexual abuse: Results of a survey in Johannesburg. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(3):275-288. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2015. Social welfare and social development. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. & HOCHFELD, T. 2011. It buys food but does it change gender relations? Child Support Grants in Soweto, South Africa. Gender & Development, 19(2):229-240. [ Links ]

PAYNE, G. 2014. Surveys, statisticians and sociology: A history of (a lack of) quantitative methods. Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences, 6(2):74-89. [ Links ]

PHETLHU, D. R. & WATSON, M. 2014. Challenges faced by grandparents caring for AIDS orphans in Koster, North West Province of South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance (AJPHERD), October 2014 (Supplement 1:2):348-359. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 1997. Ministry for Welfare and Population Development. 1997. White Paper for Social Welfare. Notice 1108 of 1997. Government Gazette, 386(18166). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2005. Children's Act (38/2005). Government Gazette. 492 (28944). [ Links ]

ROSENBERG, N. E., PETTIFOR, A. E., MYERS, L., PHANGA, T., MARCUS, R., BHUSHAN, N. L., & MTWISHA, L. 2017. Comparing four service delivery models for adolescent girls and young women through the 'Girl Power' study: Protocol for a multisite quasi-experimental cohort study. BMJ Open, 7(12),:e018480. [ Links ]

ROUX, A., BUNGANE, X. & STRYDOM, C. 2010. Circumstances of foster children and their foster parents affected by HIV and Aids. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 46(1):44-55. [ Links ]

SCHILLER, U. 2015. Exploring adolescents' participation in decision-making in related foster care placements in South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 51(2):1-14. [ Links ]

SCHILLER, U. 2017. Child sexual abuse allegations: Challenges faced by social workers in child protection organisations. Practice, 29(5):347-360. [ Links ]

SCHMID, J. 2010. A history of the present: Uncovering discourses in (South African) child welfare. British Journal of Social Work, 40(7):2102-2118. [ Links ]

SCHMID, J. 2012. Trends in South African child welfare from 2001-2010. Centre for Social Development: Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

SCHMID, J. 2014. What's on their minds? The South African Child Welfare Academic Agenda from 2001 to 2010. Social Work Education, 33(2):141-159. [ Links ]

SEPTEMBER, R. L. 2006. The progress of child protection in South Africa. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15 (Supp1): S65-S72. [ Links ]

SIBANDA, S. & LOMBARD, A.2015. Challenges faced by social workers working in child protection services in implementing the Children's Act 38 of 2005. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 51(3):332-353. [ Links ]

SILJEUR, N. 2016. Protecting children against cyber-sex in South Africa. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 17(2):95-102. [ Links ]

SINGH, A. & SINGH, V. 2014. A review of legislation pertaining to children, with particular emphasis on programmes offered to children awaiting trial at Secure Care Centres in South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 50(1):99-115. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICA. Child Care, Act 74 of 1983. Government Gazette, (9765). [ Links ]

SPIES, G., DELPORT, R. & LE ROUX, L. M. 2017. Safety and risk assessment tools for the South African child protection services: Theory and practice. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 30(2):116-127. [ Links ]

STEYN, H., VAN WYK, C. & KITCHING, A. 2017. Conceptualising a proposed support strategy for sexually abused boys in middle childhood. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(4):517-539. [ Links ]

STRODE, A. 2015. A critical review of the regulation of research involving children in South Africa: From self-regulation to hyper-regulation. Journal of South African Law/Tydskrif vir die Suid-Afrikaanse Reg, 2015(2):334-346. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, M. 2010. The implementation of family preservation services: Perspectives of social workers at NGO's. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 46(2):192-208. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, M. 2012. Family preservation services: Types of services rendered by social workers to at-risk families. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(4):435 - 455. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, M. 2013. Community based family support services for families at-risk: Services rendered by child and family welfare organisations. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(3):501-518. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, M., SPOLANDER, G., ENGELBRECHT, L. & MARTIN, L. 2017. South African child and family welfare services: Changing times or business as usual? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(2):145-164. [ Links ]

SVEVO-CIANCI, K. A., HART, S. N. & RUBINSON, C. 2010. Protecting children from violence and maltreatment: A qualitative comparative analysis assessing the implementation of UN CRC Article 19. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(1):45-56. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, V.& TRIEGAARDT, J.D. (eds). 2018. The political economy of social welfare policy in Africa: Transforming policy through practice. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

TRUTER, E., THERON, L. & FOUCHÉ, A.2018. No strangers to adversity: Resilience-promoting practices among South African women child protection social workers. Qualitative Social Work, 17(5):712-731. [ Links ]

UNICEF, UNHCR, SAVE THE CHILDREN, & WORLD VISION. 2012. A better way to protect all children: The theory and practice of child protection systems. In Conference report. New York, NY: UNICEF. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2017. A Familiar Face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents. New York, NY: UNICEF. [ Links ]

UNICEF.2017a. Violent discipline, sexual abuse and homicides stalk millions of children worldwide. Pretoria, South Africa: UNICEF. [ Links ]

VAN GRAAN, J. 2012. An impact evaluation of the restructuring of the South African Police Services Family Violence, Child Protection and Sexual Offences Units: The case of the West Rand FCS Unit. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 25(1):97-113. [ Links ]

VAN GRAAN, J., G., & SNYMAN, H., F. 2011. Value of impact evaluation of public service transformation: lessons learnt from a South African Police Service specialised unit. Journal of Public Administration, 46(4):1309-1322. [ Links ]

VAN HUYSSTEEN, J. & STRYDOM, M. 2016. Utilising group work in the implementation of family preservation services: Views of child protection workers. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(4): 546-570. [ Links ]

VAN NIEKERK, J. & MATTHIAS, C. 2019. Government and non-profit organisations: Dysfunctional structures and relationships affecting child protection services. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 55(3):239-254. [ Links ]

VAN RAEMDONCK, L.& SEEDAT-KHAN, M. 2018. A case study on a generalist service delivery model for street children in Durban, South Africa: Insights from the capability approach. Child & Family Social Work, 23(2):297-306. [ Links ]

VETFUTI, N., GOLIATH, V. M., & PERUMAL, N. 2019. Supervisory experiences of social workers in child protection services. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 31(2):1-18. [ Links ]

VIVIERS, A. & LOMBARD, A. 2013. The ethics of children's participation: Fundamental to children's rights realization in Africa. International Social Work, 56(1):7-21. [ Links ]

WALLACE-HENRY, C. 2015. Unveiling child sexual abuse through participatory action research. Social and Economic Studies, 64(1):13-36. [ Links ]

WARD, C. L., & BAKHUIS, K. 2010. Intervening in children's involvement in gangs: Views of Cape Town's young people. Children & Society, 24(1):50-6. [ Links ]

WARRIA, A. 2018. Challenges in assistance provision to child victims of transnational trafficking in South Africa. European Journal of Social Work, 21(5):710-723. [ Links ]

YOUSSEF, R., ATTIA, M., & KAMEL, M. 1998. Children experiencing violence: Parental use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(10):959-973. [ Links ]