Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.55 no.4 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-759

ARTICLES

The role of fathers receiving social grants in decisionmaking processes within poor rural households in Alice, Eastern Cape of South Africa

Nolubabalo KetaniI; Pius T. TangaII

IPhD Student Department of Social Work, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. Email:201105506@ufh.ac.za/nketani39@gmail.com ORCID Id: 0000-0001-6848-9904

IIDepartment of Social Work / Social Development, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. Email:ptanga@ufh.ac.za / tanga8_2000@yahoo.co.uk/ ORCID Id: 0000-0003-1359-8729

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the role of fathers receiving social grants in the decision-making process in poor rural households. Data were collected from a sample of 195 respondents. Data-collection methods included in-depth interviews and survey questionnaires. The findings revealed that fathers receiving social grants, together with their partners were jointly making household decisions, even though they were the ones contributing more income to the household. It was found that economic factors play a critical role in positioning other household members in decision-making. We conclude that co-operative bargaining, resulting in the distribution of power in the decision-making process, is relatively prominent in most poor rural households. The authors provide some practical social work recommendations.

Keywords: Household decision-making, father, social grants, family, wellbeing

INTRODUCTION

The family, as a primary social institution, offers a significant entry point to the household decision-making process (Booysen, Guvuriro, Campher & Mudzingiri, 2013). On a daily basis, household members make decisions regarding money, health, food, resources and social values. The life opportunities of household individuals are critically influenced by resources at the disposal of the household as well as the choices made in relation to the way such resources are allocated (Booysen et al., 2013). Such decisions are imperative in achieving various development goals such as education, health, welfare and wellbeing of family members. According to Patel, Hochfeld and Moodley (2013), the interactive relationships within households affect the decision-making process, since family members are interconnected. Therefore, intra-household decision-making on the distribution of resources affects the social welfare and economic wellbeing of all household members, especially children.

Households are also regarded as relevant units of analysis in advancing knowledge on how decisions are made within families. According to Arbache, Kolev and Filipiak (2010), the family is a complex decision-making unit that is a central element of many policy initiatives aimed at alleviating poverty. It is an effective approach of transferring income and other resources to those in need of care and protection. Social grants beneficiaries make decisions on a daily basis about the utilisation of money from social grants. These decisions have an important bearing on the intra-household dynamics and welfare of the household members. Jacobs, Ngcobo, Hart and Biapheti (2010) state that social grants have a positive effect on human development and the wellbeing of family members within households. However, according to Patel (2011), it is imperative to acknowledge that poor households may experience numerous challenges in making financial decisions regarding the acquisition of goods, the utilisation of educational opportunities and the distribution of limited resources.

Research on household decision-making suggests that changes are taking place in the attitudes and behavioural directions of family members in today's households. changes occur for a number of reasons which distort the decisions and the role structure of traditional household units (Khattak & Raza, 2012). According to Khattak and Raza (2012), these changes may involve cultural norms, family income, family life cycle and shifting societal standards. This paper evaluates the role of social grant-receiving fathers in decision-making processes within poor rural households. One-sided decision-making within households has many negative consequences for household members, such as poor interactions, anger and difficult social relationships, amongst others. More than 17 million South Africans (17,731,402) receive social grants on which many depend as their sole source of income (SASSA, 2018). The next section reviews the literature, followed by an account of the methodology and presentation of the findings. In subsequent sections, these findings are discussed and conclusions are drawn. The last section makes some recommendations.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Decision-making models are concerned with ascertaining the values, uncertainties and other issues applicable to a given decision and its rationality (Lien, Westberg, Stravros & Robinson, 2018). Households employ different decision-making models such as unitary decision-making, collective bargaining, cooperative bargaining and non-cooperative bargaining models (Ermagun & Levinson, 2016). According to Bertocchi, Brunetti and Torricelli (2014), for a long time households were assumed to work as one decision-making entity (unitary model). This model considers the household as a single and monolithic economic decision-making unit. The assumption was that all household members contribute, in a self-sacrificing manner, to the gains and effective functioning of the household (Rustichini, 2008). The presumption is that household members act altruistically and that utility is maximised when household resources are combined and distributed equitably among members. According to Lien, et al., (2018), it is also assumed that a household is an income-pooling unit characterised by communal preferences. Considering income as the sole and direct measure of financial bargaining power, the unitary model claims that household members pool their incomes and leave the spending decisions entirely up to the benevolent dictator (Njuki & Sanginga, 2013).

The collective model is an alternative approach that takes into consideration the fact that the household consists of different members who go through a bargaining process in the allocation of resources and decision-making (Molina, 2011). The identity of the household member who earns an income impacts on the way resources are distributed and how decisions are made. This model's focus is on the individuality of household members and how individual preferences result in a collective decision. There are two types of collective models: cooperative and non-cooperative (Vermeulen, 2002; Carrrero & Aleti, 2017). In a non-cooperative model every household member functions in order to capitalise on individual utility, while in a cooperative model members of the household function together as an entity to maximise the wellbeing of its members by recognising the involvement of different individuals with distinct preferences (Vermeulen, 2002).

The unitary and joint decision-making models regarding social grants have different impacts on decision-making and resource distribution within households (Lekezwa, 2011). According to the unitary model, social grants are provided to families with the aim of enhancing an individual's wellbeing. The likelihood in the unitary model is that individual household members cannot function autonomously without such a family (Kihlbom & Munthe, 2019). According to this model, social grants aimed at a specific individual within the household will be beneficial to all household members in terms of allocation of resources and welfare. Social grants are envisioned as additional income to the household, with the expectations that the transfer will improve the living standards of the household and somehow have an impact on the wellbeing of recipients (Tanga, Gutura & Tanga, 2019). The provision of unearned income to households affects the dynamics of such households, such as control and authority in decision-making. Hence, it is argued that it is basically the identity of the recipient that appears to matter (Gutura & Tanga, 2017). However, collective models assume that social grants modify the composition and distribution of income within the household (Lien, et al., 2018). These models introduce complications regarding the consequences of welfare, as outcomes are subjected to how an individual perceives his or her value as part of the household. The allocation may be biased, as households may be regarded as sites of conflict (Vermeulen, 2002). Under such circumstances, the identity of the caregiver is vital in order for social grants to become an effective instrument in poverty reduction. This paper adopts the definition of a caregiver as provided by Koopmanschap, Van-Exel, Berg and Brouwer (2008) as someone who is either a family's social network member, paid or unpaid, and assists the family in daily living activities. Caregiving, in this context, is commonly used to address impairments in households where there are old and/or disabled persons, and persons with diseases or mental disorders.

Kiani (2012) points out that decision-making processes may be classified as economic, social, instrumental and affective. Economic decisions are concerned with the allocation of limited financial resources for serving numerous household purposes. Proper allocation of money plays an important role in economic decision-making, as it involves defining which goals are important for the wellbeing of the family. Some scholars are of the opinion that poor people act differently from non-poor people when making such decisions on the basis of diverse motives (Carvalho, Meier & Wang, 2014; Akcay & Roughgarden, 2009). The arguments on the reasons underlying such differences have two contrasting sentiments: that either the poor rationally acclimatise and make optimum decisions for their economic environment, or that a culture of poverty moulds their choices and makes them more disposed to miscalculations. Among economists, this discussion has been apparent in persistent debates about whether the poor are more impatient, more risk averse and have lower self-control, which may drag them into the cycle of poverty (Gunhidzirai, Makoni & Tanga, 2017). These authors argue that shortage, which means having less than you feel you need, hinders cognitive functioning, which in turn may result in decision-making misjudgements and constrained behaviour. Social decisions are resolutions related to the principles, roles and aims of the family. These decisions are directed towards the objective accomplishment resulting from the utilisation of resources and through interaction between individuals (Patel, 2011). Decision-making may be based on available income and resources, but it also reflects the goals and values held by the family (Kiani, 2012). For example, the values of the family that embraces education influence the amount of money that the family devotes to expenses on education.

Instrumental decisions are those that focus on functional issues such as providing money, shelter and food for the family (Segrin & Flora, 2011). In the past fathers were responsible for working and providing for their family members. They were more likely to define the norms of instrumental decision-making. However, changes are taking place regarding the roles of women in instrumental decision-making as they are now also contributing towards the resources of the family (Patel, 2011) and more involved in instrumental decision-making.

Affective decisions deal with choices associated with feelings and emotions. As the individual makes decisions, interactions that are influenced by values and role perceptions take place (Kiani, 2012). The affective decisions of households regarding developing and supporting individual members entail promoting and protecting the health of household members as well as imparting moral and social beliefs to them, with the general aim of ensuring that the next generation is resourceful and socially accountable (Patel, et al., 2013). To implement these decisions, parents or other family members use considerable guidance as role models of healthy and competent behaviour.

In the process of decision-making individual family members play different roles that are not permanent or equally exclusive, as decision-making changes between family members and over time. Family members may assume the role of initiator, gatekeeper, influencer, decision-maker, buyer and consumer (Sethna & Blythe, 2016). Parents have to distinguish between their own interests and those of their children in an attempt to balance family needs. The nature of contributions and needs may change from childhood to adulthood (Patel, et al., 2013). Therefore, effective allocation and distribution of resources is crucial in encouraging intergenerational trust, as well as economic and social stability. The individual's power to make decisions is based on the capability to provide for the fulfilment of the basic needs of family members. Thus, if grant-receiving fathers fulfil their responsibility to provide, their partners will allow them to define the norms of decision-making (Gutura & Tanga, 2015).

Households in South Africa are private care nets for individuals who are unemployed and who have to benefit from the resources within the household. It is imperative for beneficiaries of social grants to be empowered to be in a better position to deal with challenges associated with making decisions on how to utilise money received from social grants. Understanding such dynamics can enlighten beneficiaries and family members on how best to deal with unforeseen consequences. The literature review shows that much attention has been paid to modern family decision-making in households, but with little attention devoted to the African decision-making process of fathers receiving social grants in South Africa. The findings of this study will make a contribution to the existing body of knowledge in terms of family decision-making processes and utilisation of social grants. The study is therefore an attempt at advocacy that goes beyond redefining caregiving as a gendered experience. It raises awareness about the concept of male caregiving through use of social grants. The intention of this study was not to reduce the contributions of mothers and grandmothers in their caregiving roles, but to allow society to carefully listen to the voices of fathers who are providing care for their family members through their grant money. The study will also assist professionals involved in the welfare system to gain insights into the dynamics of decision-making in extended families, including financial decision-making by grant-receiving fathers. The paper examines the role of fathers receiving social grants in household decision-making processes in rural South Africa, where patriarchal ideology is still rife.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The South African government has implemented several programmes to alleviate poverty among its citizens. One of the major strategies is cash transfers that form part of social assistance and protection programmes to deprived and vulnerable people (Patel, et al., 2013; Tanga, Gutura & Tanga, 2019). According to Potts (2012), social assistance is crucial in the fight against insecurity and vulnerability among the poor. It also assists in accessing opportunities, and in alleviating and reducing poverty. Shepherd, Wadugodapitiya and Evans (2011) point out that South Africa's system of social security significantly decreases poverty, and the progressive expansion of the extent, scope and accessibility of cash transfers has the potential to radically decrease the prevalence of poverty. Cash transfers are effective in addressing the challenge of hunger, as well as meeting basic needs in general; they are positively related to a larger share of household spending on food (Gutura & Tanga, 2017). It has been claimed that social grants are more probable to be pooled to deal with general household expenses rather than consumed solely by the targeted groups (Department of Social Development, 2008). In other words, social grants have a positive impact beyond the individual recipients. However, according to Surrender, Noble, Wright and Ntshongwana, (2010), there are challenges in the usage of social grants. They postulate that there are instances where recipients of social grants waste money on alcohol or on other unproductive ways as opposed to using it constructively for meeting the basic needs of beneficiaries. This misuse leads to malnourishment among household members, especially children. The basic needs of members of the household will not be catered for and developmental needs will be affected. This may negatively affect their dependents physically, emotionally or psychologically, cognitively and socially, and perpetuate poverty to the next generation. As a result, the living standards of targeted groups (children, elderly and disabled people) will not improve. The social functioning of individuals from these households, their families as well their communities will also be negatively affected.

In order to address the aim of the study, the main research question that guided the study was: What is the role of the father in decision-making on the use of social grants within the family? Two specific research sub-questions included: How is the money received from social grants used by beneficiaries (fathers)? How does the decision-making of fathers about social grants impact on the wellbeing of family members?

STUDY AREA AND METHODS

The study was conducted on households with fathers receiving social grants in Nkonkobe Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape province (South Africa). According to Nkonkobe Municipality IDP (2017), Nkonkobe (now Raymond Mhlaba) Municipality has a population of about 127 215. About 72% of the population stays in rural communities. The municipality is characterised by high levels of unemployment and poverty is a major concern (Nkonkobe Municipality IDP, 2017). Approximately 48% of the overall population is unemployed, while 85% survives below the poverty line of R1 500 per month and only 15% are receiving a reasonable income (Statistics South Africa, 2011). Consequently, 61% of households receive social security grants (Statistics South Africa, 2011).

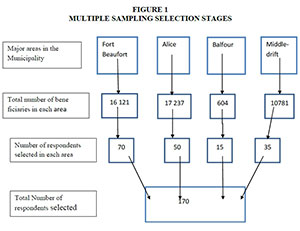

A mixed method approach was employed. Both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods were used. The population of this study consisted of all beneficiary households (fathers, mothers and children) receiving social grants as well as caregivers in Nkonkobe. Two sampling strategies were used, namely multi-stage sampling and purposive sampling. The multi-stage sampling strategy described below was used in selecting the 170 household beneficiaries of social grants. Nkonkobe municipality is divided into four major areas for administrative purposes and these include Fort Beaufort, Alice, Middledrift and Balfour. In multi-stage sampling the first stage was to find out the total number of households receiving social grants in each major area. At the second stage, in each major area, and based on the total beneficiaries, 70 beneficiaries were selected from Fort Beaufort, which had 16 121 social grant recipients; 50 were selected from Alice, with a total recipients of 17 237; 15 recipients from Balfour, with 604 recipients, and 35 from Middledrift, with 10 781 recipients. Thus, in a multi-stage sampling procedure, the units of study were selected in a random manner from lists obtained from SASA Offices. In cases where some households were not identified through their councillors, they were replaced. The multi-stage sampling is shown in Figure 1 below.

The second method of data collection was in-depth interviews with 25 caregivers in households where there were social grant recipients. The sample was purposively selected from the four main areas that make up the municipality, and this was based on their willingness to participate in the interviews. The selection took place at the different paying stations during pay-out periods. The study used a survey method that made use of questionnaires administered to 170 households that were receiving social grants. The questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions - with a Likert scale whereby the responses could choose strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree or strongly disagree - as well as closed-ended questions. The second set consisted of 25 participants (caregivers) living with fathers receiving social grants who were interviewed using in-depth interview guides. Quantitative data were coded on Microsoft Excel package and run using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software for analysis. The results were then presented in percentages. Qualitative data were analysed using content analysis as recommended by De Vos (2010); this involves detailed descriptions, direct quotations in response to open-ended questions, and the transcripts of the opinions of the participants.

Reliability and validity

The researchers ensured that the questionnaire was subjected to stability reliability, which is reliability across time. This was done through piloting of the questionnaire to ten respondents who did not participate in the study. Also, to ensure the validity of the data-collection instrument (questionnaire), face validity was adopted. This refers to a type of validity that is commonly accepted or agreed as a measure of a phenomenon. Therefore, the questionnaire was judged valid by the researchers and colleagues.

Trustworthiness and ethical clearance

Trustworthiness was based on Guba and Lincoln's (1994) constructs of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. The instruments of data collection were constructed for analysing data generated in a systematic way. The researchers independently analysed the data and had face-to-face meetings to reach consensus. The authors critically examined the responses to verify the credibility of the findings. Thick descriptions of the research process were also provided. These descriptions provide opportunities for other researchers to replicate the study, as indicated by Creswell (2014). The authors also provided direct quotations from the data as evidence to support the findings and assist with confirmability. Finally, ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of Fort Hare Ethics Committee (Ethical Clearance Number TAN08 1STEK0 1). This was supplemented by authorisation from the councillors of the four areas in the municipality. The following ethical principles were observed: confidentiality and voluntary participation, as suggested by Leedy and Ormrod (2013). The participants were informed that their names would not be used when reporting the findings. The participants signed informed consent form to show that they understood the study's objectives, which the researchers had explained to them.

FINDINGS

This section provides the biographical information of the participants. The next section deals with the findings on decision-making patterns; participation of other household members in decision-making process; and decisions regarding the allocation of social grants. The last section provides findings about purchase decision-making, health decisions and decisions concerning education of children.

Biographical information of participants

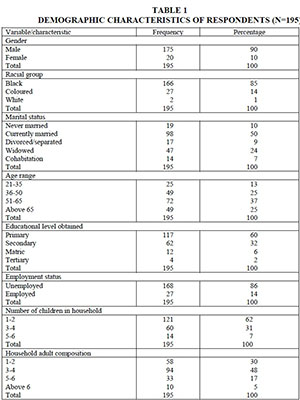

A variety of questions were asked to get the demographic information from the participants, and the information is indicated in Table 1 below.

According to Table 1, 90% of the participants were males and 10% were females. The highest number of respondents were Black (85%), followed by Coloured respondents (14%), as shown on table 1. Only two participants (1%) of the study were White. There were no Indian participants. Table 1 reveals that among the total respondents (N=195), 37% were between 51 and 65 years, 25% were over 65 years, and another 25% were aged between 36 and 50 years, whilst 13% were aged between 21 and 35 years. Regarding age, Table 1 indicates that the majority of respondents fell within the 51-65 years age, followed by respondents older than 65 years and those between 36 and 50 years. The lowest number of respondents fell within 21-35 age bracket. In terms of marital status, the majority of respondents were married (50%), 24% were widows, 10% were single, 9% were divorced and the lowest number was in the cohabitating category made up of 7% of the respondents.

In addition, the Table shows that the levels of educational qualifications were primary, secondary, matric and tertiary education. Respondents who had primary education were the highest in number (59%). Thirty-two percent (32%) had secondary education; 6% had a matric qualification, whilst only 2% of respondents had tertiary education. Concerning the adult composition of their households, the majority of respondents (62%) indicated that they were living with one or two adult family members; 31% of respondents had between three and four adults in their households, while 7% revealed they were living with five or six adults in their households. There were no respondents living with more than six adult members. To further understand the composition of households, respondents were requested to specify the number of children staying in the household. The results show that most respondents (48%) cited that they stayed with three to four children, followed by those who stayed with one to two children (30%). Those who stayed with five to six children numbered 17%, and 5% stayed with more than six children. However, no respondents indicated that they stayed in a household with no children. Lastly, respondents were requested to indicate if they were employed or not at the time of completing the questionnaire. According to Table 1, the findings revealed that 86% (majority of respondents) were unemployed and only 14% were employed. These results indicate that unemployment is a serious challenge in Nkonkobe (Raymond Mhlaba) Municipality. Social grants were the main, if not the only, source of income within most households.

There are five major types of social grants in South Africa, namely old age grant, disability grant, child support grant, foster care grant, and care dependency grant. Respondents were requested to indicate the types of social grants that they were receiving. The results show that respondents were receiving four main types of grants out of the five major types. Fifty-eight per cent (58%) of respondents (the majority) were receiving the old age grant, 19% of respondents were receiving the disability grant, 18% were recipients of the foster care grant, while 5% of respondents were beneficiaries of child support grants. Regarding the number of household members receiving social grants, the findings show that there were other family members who were receiving social grants within the households of respondents. Sixty-two percent (62%) of the respondents indicated that they were not the only household members receiving social grants, while 38% of the respondents indicated that fathers were the only beneficiaries of social grants within their households. The in-depth interviews revealed that other family members receiving social grants within the households were mostly females (receiving child support grants)

Decision-making patterns

The respondents were asked if their families acted as a team when making various household decisions. The quantitative results show that most respondents (59%) agreed that they made decisions jointly. Out of the 59%, a total of 39% agreed while 20% strongly agreed. On the other hand, 38% of respondents indicated that they did not act as a unit when making decisions (24% disagreed and 14% strongly disagreed). Three percent (3%) of respondents were undecided. The qualitative findings indicate that participants had different responses. Out of the 25 participants interviewed, the majority revealed that they made family decisions collectively. Participant 4 (a 55-year-old woman) indicated that:

"Both my husband and I make decisions together, we share equal power. Joint participation plays an important part in care giving roles. Listening to different views and functioning as a team puts our family in a better position to meet basic needs."

However, some participants had different views. One family member had authority in family decision-making. A 41-year-old wife (Participant 3) pointed out that:

"My husband is the one who is making decisions in my family. We don't share leadership. This has a negative effect on the social functioning of our family."

Participation of other household members in decision-making process

The study sought to ascertain whether the respondents were involving other family members in the decision-making process (besides the father and the partner). The results from the survey indicate that 61% of respondents involved other family members in decision-making. Of this number, 26% strongly agreed while 35% agreed. However, 38% of respondents disagreed with the statement, 17% strongly disagreed and 21% disagreed. One per cent were neutral, indicating that sometimes they involved other family members in decision-making but sometimes they did not. The in-depth interviews revealed that most participants involved other family members in making decisions. Participant 20 (a 55-year-old woman) stated that:

"My husband allows adult family members to participate in family decision-making process. The decisions affect each other as family members are interdependent. Participation of all adult family members is crucial for the wellbeing of our family."

Most researchers are of the opinion that other household members influence family decisions. Consequently, respondents were requested to indicate the family members whose views and concerns they listened to in making decisions. The data from quantitative results show that 34% of respondents listened only to adult family members, 10% listened to all family members (both old and young family members), 25% considered the opinions of both partners and children, 24% revealed they considered ideas from unemployed family members, while 8% maintained that they listened only to family members who had an income and contributed to household expenses.

The in-depth interviews revealed that most fathers involved their partners in decision-making, even though they were not working. However, for the involvement of other family members, the scenario was slightly different; their ability to bring income to the household had an influence on their participation in decision-making. Children were also emerging influencers in the decision-making process. Participant 18 (a 34-year-old daughter) indicated that:

"My father includes us in decision-making, although we are not working, to reduce family tensions and conflicts."

Additionally, participant 14 (a 21-year-old son) claimed that:

"Children do not make decisions but my father listens to our views before making choices so that he can be more informed of our individual needs."

Decisions regarding the allocation of social grant money

Decisions about proper distribution of social grants play a vital role in the wellbeing of members of households among underprivileged families. The quantitative data indicated that 33% of the respondents involved their partners when making decisions about the allocation of social grants, 25% made decisions on their own, 22% involved all adult family members, 13% involved children, while 4% of the respondents indicated that their partners were the ones who made decisions regarding the allocation of social grants. Only 3% of the respondents revealed that other adult family members were making decisions regarding social grants on their behalf without them. Regarding the qualitative data, most participants indicated that although different household members shared decision-making power on the allocation of social grants within households, the husband and the partner were the principal decision-makers. Participant 20 (a 55-year-old wife) stated that:

"My husband includes me when allocating social grants money. Social grant is the only income we have as a family. My husband believes that making decisions together empowers our family to be in a better position to budget for basic needs."

A few participants revealed that fathers were making decisions on their own regarding the allocation of money received from social grants. Participant 21 (a 54-year-old wife) declared that:

"My husband is making decisions about the allocation of social grant money. I am not working, and he is the only family member that has income."

Purchase decision-making

Family members depend on one another for survival. They require enough food, warmth, shelter and healthy surroundings. Therefore, the decision-making process within the family structure regarding the well-being of family members is crucial, especially financial decisions. Hence the respondents were requested to indicate who decides on what to purchase with money received from social grants. The findings from the quantitative survey suggest that 26% of respondents jointly made decisions with their partners relating to purchases, while 23% of the fathers indicated that they made decisions on their own. Additionally, 19% of the respondents made collective decisions with all adult family members staying in the household, and 13% of the respondents indicated that their partners were the principal decision-makers regarding the utilisation of social grants. A further 13% revealed that children had an influence in decisions, while 6% maintained that other adult family members made decisions regarding purchases with money received from social grants. The qualitative results from the interviews reveal that family members performed different roles in terms of making decisions regarding purchases. Participant 3 (a 41-year-old wife) stated that:

"Although my husband and I make purchase decisions together, children influence such decisions. We consider what type of food they like and what is good for their health. We consider our different preferences and try to compromise and balance individual needs with those of all family members."

Participant 19 (a 57 year old wife) maintained that:

"I am the one who plays the role of being a buyer in my family. I am the one who knows what type of foods are essential for my family members, especially for children. "

Health decisions

Allocation of social grants within households is perceived to have an impact on nutrition and food consumption, which are vital components of the health condition of family members. Making decisions about health care can seem overwhelming at times. The results from the quantitative data indicate that most decisions regarding health were made by fathers (representing 30% of the total number of respondents), 24% of the respondents involved their partners in making decisions, 19% indicated that their partners made decisions regarding health within their families, 11% maintained that all adult family members were involved in decisions concerning health issues of family members, 9% indicated that other adult family members within the family made decisions regarding health, while only 6% of respondents pointed out that other people, besides those mentioned above, made such decisions. The interviews also revealed that decisions on health matters were mostly made by fathers. Many participants agreed that fathers made health-related choices, while other participants had different views on how decisions regarding health matters were made. Participant 7 (a 45-year-old wife) stated that:

"My husband makes health decisions. He is the only one receiving income in the household and knows if we can afford medical expenses or we have to go to the government health centres providing such services free."

On the other hand, participant 19 (a 57-year-old mother) said that:

"My partner and I make health decisions together. The exclusion of certain family members from these crucial decisions can compromise the health and wellbeing of all family members, particularly children."

Decisions concerning education of children

Making decisions regarding the education of children is one of the key moments when parents reflect on what is important in terms of the education of children. The findings from the quantitative data show that there were a range of reactions regarding the education of children. Most respondents (30%) indicated that, regarding the education of children, fathers receiving social grants made decisions on their own without consulting other family members, 21% indicated that they involved their partners in making decisions, 19% revealed that their partners made decisions on the education of children, while 15% of the respondents pointed out that other adult family members were responsible for making decisions regarding the education of children, and 15% maintained that children were the ones responsible for deciding which school they attended.

Participants also raised different responses regarding the education of children. Most participants indicated that parents made decisions regarding the education of children who were in day-care centres and primary schools. However, as children grow older and start secondary education, they make their own schooling choices. Participant 24 (a 37-year-old wife) declared that:

"We both make schooling decisions together with my husband. Career development of our children is imperative to us. We are not educated, but we want our children to get the best education, so that they can get better jobs and break the cycle of poverty in our family."

However, participant 13 (a 59-year-old partner) stated that:

"My children make their own schooling decisions. We used to make decisions for our children while they were in secondary school; but now they are at tertiary level."

Indications are that the older children were involved in making decisions relating to their education.

DISCUSSION

Most fathers receiving social grants are making household decisions collectively through bargaining and cooperative models. These results correspond with those of Molina (2011), who argues that collective decision-making is more likely to occur within poor households covering several generations. Modern family decision-making processes are characterised by a high degree of joint participation in taking decisions, resulting in fathers and partners sharing decision-making power within households (Tetley, Grant & Davies, 2009). The participation of women in household decision-making has positive effects on the wellbeing of household members, promoting family welfare. Even though in most households decisions are made collectively, as also reported by Kihlbom and Munthe (2019), there is an indication that such decisions are closely related to the preferences of fathers. This is largely because fathers are most often those family members bringing in an income in most households; hence, they have more influence and control. This analysis finds support in the resource theory, which states that family power is influenced by the relative value of resources that each partner brings to the household. For this reason, a person with more resources has more control in decision-making (Bettner, 2015).

There are still households that follow the traditional distribution of power where there is a single decision-maker. According to Bettner (2015), the responsibility of a primary decision-maker in such relationships is to earn income, while the partner is responsible for child care. In such scenarios, the household is treated as an individual decision-maker and disregards intra-household decisions totally (Lien, et al., 2018). Participants pointed out that modelling single roles in decision-making can have detrimental effects on the wellbeing of all household members, especially on children, since women are excluded from household decision-making processes. These findings are in line with the unitary model of decision-making, which assumes that the family functions as a single decision-making entity, directed by a principal decision-maker with no joint decision-making (Njuki & Sanginga, 2013).

However, the participation and inclusion of views of other household members in family decision-making is subject to economic factors such as income, employment status and age, which are considered as social factors. The results are in agreement with Lekezwa (2011) who states that having a job, or receiving any type of social grant, assists in strengthening the decision-making power of household members. Household members who contribute financially to the household are more likely to be involved in family decisions, since the contribution to household income influences the level of control and power. Consequently, young unemployed adults and children have very limited decision-making power as also noted by Chaudhary (2018) and Tomic, Lekovic, Marie and Paskas (2018).

Most respondents were making decisions on expenditure collectively. Participants suggested that they pooled household resources jointly and allocated them towards satisfying different individual preferences. These results corroborate those of Kiani (2012), who postulates that in the bargaining type model of intra-household decision-making, household members reconcile their different preferences in a cooperative manner. Participants further maintained that collective distribution of income in household expenditure is a good thing, as it leads to an efficient use of available resources. Thus, the manner in which members of households choose to allocate their resources determines the levels of nutrition, health care, education and protection. Fathers had the upper hand in decisions regarding huge expenditures, while their partners were often final decision-makers regarding everyday household expenditure. These findings are in agreement with the findings of a study conducted by Booysen et al. (2013) which found that daily spending decisions made by the wife were better than those jointly made. Booysen et al. (2013) argue that financial decision-making power vested in the female partner significantly increased expenditure on food, utilities, health care and education.

Children had some influence in purchase decisions, although they did not make independent decisions. They had more impact on decisions regarding toys, clothing and food, but minimal say in large purchases. These results are in agreement with Oyewole, Peng and Choudhury (2010), who found that the role of parents as the main decision-makers regarding purchase in families is changing; the buying process has shifted slowly towards accommodating children as their role has become more important than before. Collective bargaining on decisions on expenditure also has significant inter-generational implications on education and health as well as the wellbeing of family members. It influences the inter-generational transmission of poverty as well as the potential for upward mobility on the quality of life across generations.

Most fathers are primary decision-makers regarding schooling and health-related issues. Women from poor communities often lack financial resources and fathers receiving an income in households end up being primary decision-makers regarding health (Kiani, 2012). However, women play a critical role in making such decisions, especially for children. Women make decisions on which schools to attend, medicines to take, health treatments to follow and doctors to see, and how to live a healthy lifestyle. However, there are instances where gender-centred power inequities constrain communication among spouses and other household members about health decisions and this, in turn, contributes to poor health consequences for all household members, as suggested by Kihlbom and Munthe (2019). In terms of schooling decisions, parents invest in children's education with the hope that in future they will be able to rely on them for economic support and to break the cycle of poverty (Tanga, 2013). Children have an influence on deciding which school to attend to avoid them dropping out of school. Even though participants indicated that there was a growth in women's participation in decisions regarding health and education, men still remain key decisionmakers. The gender gap in the ownership of income is one of the most critical contributors to such decisionmaking inequalities (Patel, et al., 2013). The decision-making authority of women in expenditure is less among poor households, partly because in such households the likelihood that women will be primary contributors of household income is much lower.

CONCLUSION

Joint or collective decision-making is relatively prominent in most poor households. This signifies that household members agree on the distribution of bargaining power, which emphasises the importance of gender empowerment in the decision-making process. However, economic factors play a critical role in positioning other household members in family decision-making. Children and unemployed household members have very limited decision-making power. Notably, financial decision-making is affected by factors such as the environment, maintenance needs the and interrelatedness of family decisions. Decisions on household expenditure and resource distribution are crucial for maintaining economic and human capital. These decisions influence the welfare of individuals living within the household and are key developmental issues. It is evident that within households with precarious opportunities, intra-household dynamics of decision-making and resource distribution have a bigger influence on the wellbeing of the entire household. Even though the results revealed that decisions regarding expenditure in poor households are mostly made jointly by fathers and their partners, there are indications of increased women's participation in decision-making; yet males remain key decision-makers in most areas, as they are the major contributors to household income. Therefore the ability of poor women to contribute to household expenses through income affects their power in decisions on expenditure.

Decision-making within poor households remains an important topic, because there is joint consumption of a number of goods from the same scarce resources in order to satisfy the needs of individual household members. In households with low income and extended families, it is crucial to understand how these circumstances shape decision-making processes and impact on decision-making outcomes, including the provision of goods and services within the household. Individual life opportunities are adversely affected by both material resources at the disposal of the household as well as decisions taken within the household regarding how such resources should be distributed. Therefore, the role played by fathers receiving social grants is crucial for the wellbeing of all household members, since they are the ones bringing resources to the household, and presumably having more influence in decision-making. Finally, one can argue that there is a fundamental shift from traditional male decision-making towards collective or joint decision-making on the use of social grant money within rural households, and this should be encouraged throughout South Africa. The monopoly of fathers making decisions about the use of social grant money seems to be diminishing rapidly.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings, the authors propose the following recommendations: families receiving social grants should be encouraged by social workers to embark on joint decision-making on the use of the grants to avoid conflict; social workers should also educate families on financial planning so as to avoid misuse of social grant money by stronger members to the detriment of the household members. In addition, this study advocates responsive and compassionate social policies and programmes that will reduce the burden of all caregivers and seek to enhance kinship and family relationships in the caregiving context. Finally, any misuse of social grants to the detriment of the family members should be brought to the attention of social workers.

It is suggested that further studies could each focus on specific household decision-making processes in relation to things like health, education, purchases and recreation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg in the Republic of South Africa towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not to be attributed to the Centre of Excellence in Human Development.

REFERENCES

AKCAY, E. & ROUGHGARDEN, J. 2009. The perfect family: Decision making in biparental care. PLoS ONE, 4 (10): 1-10. [ Links ]

ARBACHE, J. S.; KOLEV, A. & FILIPIAK, E. 2010. Gender disparities in Africa's labour. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

BERTOCCHI, G.; BRUNETTI, M. & TORRICELLI, C. 2014. Who holds the purse strings within the household? The determinants of intra-family decision making. International Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 101:65-86. [ Links ]

BETTNER. M.S. 2015. Using accounting & financial information: Analyzing, forecasting & decision making. E-Book: Business Expert Press. [ Links ]

BOOYSEN, F., GUVURIRO, S., CAMPHER, C. & MUDZINGIRI, C. 2013. The who's who of decision-making in South African households? Paper presented to the Biennial Conference of the Economic Society of South Africa (ESSA). University of Free State: Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

CARRERO, I. & ALETI, T. 2017. Decision making between Spanish mothers, fathers and children. Young Consumers, 18 (3): 245-260. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, L. S.; MEIER, S. & WANG, S.W. 2014. Poverty and economic decision making. Evidence from Changes in Financial Resources at Payday. New York: Columbia University. [ Links ]

CHAUDHARY, M. 2018. Pint-size Powerhouses: A qualitative study of children's role in family decision-making. Young Consumers, 19 (4): 345-357. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. 2014. Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2008 Progress report. Pretoria: Department of Social Development, Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

DE VOS, A.S. 2010. Qualitative data analysis and interpretations. In: De Vos, A.S. Strydom, H., Fouche, C.B. and Delport, C.S.L. (eds). Research at grassroots for the social sciences and Human Sciences professions (3rd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik publishers. [ Links ]

ERMAGUN, A. & LEVINSON, D. 2016. Intra-household bargaining for school trip accompaniment of children: A group decision approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy & Practice, 94: 222-234. [ Links ]

GUBA, E.G. & LINCOLN, Y.S. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (eds). Handbook of qualitative research (105-117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GUTURA, P. & TANGA, P.T. 2015. Twenty years of democracy: South African social assistance programme revisited. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 27 (1): 65-88. [ Links ]

GUTURA, P. & TANGA, P. T. 2017. 'Income for the whole family': Exploring the contribution of social grants to rural household income in Ngqushwa Municipality, Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 50 (1-3): 170-179. [ Links ]

GUNHIDZIRAI, C.; MAKONI, M.; & TANGA, P.T. 2017. Child support grants and poverty reduction in Hill Crest community, Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 51(1-3): 70-78. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2017.1305572 [ Links ]

JACOBS, P., NGCOBO, N., HART, T. & BAIPHETI, M. 2010. Developmental social policies for the poor in South Africa. Exploring Options to Enhance Impacts. Johannesburg, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

KHATTAK, J. K. & RAZA, K. 2012. Dynamics of family buying decision and mediation of conflict resolutions. African Journal of Business Management, 7 (15): 1196-1201. [ Links ]

KIANI, M. 2012. How much are women involve in decision making in family in Iran. Sociology Study, 2 (6): 417-427. [ Links ]

KIHLBOM, U. & MUNTHE, C. 2019. Health care decisions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

KOOPMANSCHAP, M.A.; VAN EXEL, J.N.A.; BERG, B. & BROUWER, W. 2008. An overview of methods for evaluating informal care in economic health studies. PharmacoEconomics - Italian Research Articles, 10: 99-111. [ Links ]

LEEDY, P.D. & ORMROD, J.E. 2013. Practical research planning and design (10th ed). Harlow: Pearson. [ Links ]

LEKEZWA, B. I. 2011. The impact of social grants as anti-poverty policy instruments in South Africa. An analysis using household theory to determine intra household allocation of unearned income. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch (M thesis) [ Links ]

LIEN, N., WESTBERG, K., STAVROS, C. & ROBINSON, L.J. 2018. Family decision-making in an emerging market: Tensions with tradition. Journal of Business Research, 86:479-489. [ Links ]

MOLINA, J. A. 2011. Household economic behaviours. International Series on Consumer Science. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

NJUKI, J. & SANGINGA, P. C. 2013. Women, livestock ownership and markets. Bridging the gender gap in Eastern and Southern Africa. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

NKONKOBE MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATION DEVELOPMENT PLAN (NM IDP). 2017. Nkonkobe Municipality Integration Development Plan 2016-2017. [Online] Available: http://www.nkonkobe.gov.za [Accessed on 18/05/2017] [ Links ]

OYEWOLE, P., PENG, K. C. & CHOUDHURY, P. K. 2010. Children's influence on parental purchase decisions in Malaysia. Innovative Marketing, 6 (4): 8-16. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2011. Poverty, gender and social protection: child support grants in Soweto, South Africa. Journal of Policy Practice, 11 (1-2): 106-120.https://doi.org/10.1080/15588742.2012.625344 [ Links ]

Patel , L.; Hochfeld, T. & Moodley, J. 2013. Gender and child sensitive social protection in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 30 (1): 69-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.755872 [ Links ]

POTTS, R. 2012. Social welfare in South Africa: Curing or causing poverty? Penn State Journal of International Affairs, 1: 74-92. [ Links ]

RUSTICHINI, A. 2008. Dual or unitary system? Two alternative models of decision making. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 8 (4): 355-362. [ Links ]

SASSA 2018. Fact Sheet : A statistical summary of social grants in South Africa. Issue No.21. Pretoria: SASSA. [ Links ]

SEGRIN, C. & FLORA, F. 2011. Family communication (2nd ed). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

SETHNA, Z. & BLYTHE, J. 2016. Consumer Behavior (3rd ed). London: Sage Publication Ltd. [ Links ]

SHEPHERD, A., WADUGODAPITIYA, D. & EVANS, A. 2011. Social assistance and dependency syndrome. Policy Brief 22. Manchester: Chronic Poverty Research Unit, University of Manchester. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA (Stats SA). 2011. Census 2011 Statistical release. Republic of South Africa: Pretoria. [Online] Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za. [Accessed on 14/06/2015]. [ Links ]

SURRENDER, R., NOBLE, M., WRIGHT, G. & NTSHONGWANA, P. 2010. Social assistance and dependency in South Africa: An analysis of attitudes to paid work and social grants. Journal of Social Policy, 39 (2), 230-221 [ Links ]

TANGA, P.T. 2013. The impact of declining extended family support system on the education of orphans in Lesotho. African Journal of AIDS Research, 12 (3): 173-183. [ Links ]

TANGA, P.T., GUTURA, P. & TANGA, M.N. 2019. The extended family support to older persons in the context of government social grant provisioning in South Africa. Dirasat: Human and Social Sciences Journal, 46 (1, Suppl. 2): 187-197. [ Links ]

TETLEY, J., GRANT, G. & DAVIES, S. 2009. Using narratives to understand older people's decisionmaking processes. Qualitative Health Research, 19 (9): 1273-1283. [ Links ]

TOMIC, S., LEKOVIC, K., MARIC, D. & PASKAS, N. 2018. The role of children in family vacation decision-making process. TEME: CasopiszaDrustveneNauke, 42 (2): 661-677. [ Links ]

VERMEULEN, F. (2002). Collective household models: Principles and main results. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16 (4). 533-564. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00177 [ Links ]