Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.54 n.4 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/54-4-674

ARTICLES

Challenges for rehabilitation of sentenced offenders within the framework of unit management in the Department of Correctional Services: Bethal Management Area

Jumari du PlessisI; Antoinette LombardII

IPostgraduate Student

IIDepartment of Social Work & Criminology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In 1998 the Department of Correctional Services (DCS) made a paradigm shift from being purely punitive institutions to becoming rehabilitative correctional centres. The paper reports on a mixed method study done at correctional centres in the Bethal Management Area. The goal was to explore and describe how rehabilitation and unit management can be optimised to address the needs of offenders. The study concludes that in order to optimise rehabilitation and unit management, the Department of Correctional Services needs to prioritise the strengthening of human resources, including professionals, provide resources, increase vocational training opportunities for offenders, and improve infrastructure within correctional centres.

INTRODUCTION

Since the commitment of the Department of Correctional Services (DCS) in 1998 to rehabilitate offenders and facilitate their social reintegration (Mohajane, 1998:8), the services and programmes have been scrutinised, adjusted and changed to suit the vision and mission of the Department, namely to provide "the best correctional services for a safer South Africa" in order to contribute to a "just, peaceful and safer South Africa" (DCS Annual Report, 2016:23). The objectives of the rehabilitation process, as summarised in The White Paper on Corrections in South Africa, firstly, focus on correcting offending behaviour, secondly, on enhancing human development, and thirdly, promoting social responsibility and positive social values amongst offenders (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:20). According to the DCS Unit Management Policy (n.d.:3), "the Department believes that rehabilitation and prevention of recidivism are best achieved through care, correction and development and by utilising unit management as a vehicle towards coordination of all these activities". Unit management therefore has the ability to enhance the rehabilitation process of offenders and ultimately contribute to the achievement of the vision and mission of DCS.

The paper reports on a study that aimed at exploring and describing how rehabilitation and unit management can be optimised to address the needs of offenders in the Department of Correctional Services, particularly in the Bethal Management Area, from a social work perspective. Firstly, the interaction between rehabilitation and unit management within the DCS is outlined. Next, the research methodology is discussed, followed by a presentation and discussion of the findings. Conclusions are then drawn and finally recommendations are made on how rehabilitation and unit management can be optimised in the DCS.

Interaction between rehabilitation and unit management in DCS

The Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, Advocate Michael Masutha, indicated that during the 2016/2017 financial year the DCS will "accelerate delivery, and place humane and safe detention at the forefront of our work to rehabilitate and successfully reintegrate offenders, which will result in the reduction of repeat offending" (DCS Annual Report, 2016:12). This statement is underpinned by documents and legislation such as the DCS Strategic Plan (2010:51), the White Paper on Corrections in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:127) and the Correctional Services Act 111 of 1998, which formed the basis for the design of the Offender Rehabilitation Path (ORP). The ORP is described in the DCS Offender Rehabilitation Path Orientation Guide (2007:8) as a document that illustrates what happens with an offender from the point of entering a correctional centre to the point where he/she is reintegrated into society. The focus in the ORP is the rehabilitation of offenders throughout the different phases of serving an imprisonment sentence. It starts with the 'Admission' and 'Assessment phases', where a Case Administration Officer (CAO) formulates the Correctional Sentence Plan (CSP) that contains all the rehabilitation programmes that the offender should attend during his sentence (DCS Offender Rehabilitation Path Orientation Guide, 2007:11). According to Bruyns (2007:101), causal factors such as unemployment, poor career training, poor mental health, a low level of education, substance abuse, unsatisfactory social life, inadequate housing, dysfunctional family and living in informal settlements all form part of the rehabilitation model that has as premise that people commit crimes because of circumstances beyond their control. The rehabilitation model does not deny that people make a conscious choice to break the law, but it does assert that such choice is not a matter of pure free will; it is determined by or at least influenced by a person's social surroundings, psychological development or biological make up (Birzer & Roberson, 2004:50; Cullen & Jonson, 2012:25). The focus of the sentence plan should be to address such causal factors of each individual sentenced offender. The ORP provides direction to all correctional officials as well as to the offender, within the framework of unit management which should serve as the vehicle for reaching rehabilitation goals.

Unit management, as defined by Stinchcomb (2011:602), is 'a decentralised approach in which a unit manager, case manager and counsellor, along with supportive custodial, clerical and treatment personnel maintain full responsibility for providing services, making decisions and addressing the needs of inmates assigned to a living unit. It makes provision for the division of the prison into smaller manageable units, improved interaction between staff and offenders, improved and effective supervision, increased participation in all programmes by offenders, enhanced teamwork and a holistic approach, as well as creation of mechanisms to address gangsterism (Singh, 2005:35). Allocating a smaller more manageable number of offenders to a Case Officer (CO), who is responsible for the implementation of the CSP and functions according to the principles of unit management, increases the possibility of effective rehabilitation of offenders.

As part of rehabilitation, offenders should be subjected to rehabilitation programmes, which should result in rehabilitation and successful re-integration into the community after release, according to the White Paper on Corrections in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:62). Social workers form part of the team responsible for presenting rehabilitation programmes. Other team members include, firstly, professional correctional officials such as educationists, psychologists and health care professionals, and secondly, the correctional officials, who include the heads of the centres, unit managers, case management supervisors, case administration officials, case officers, case intervention officials, spiritual care workers, safe custody officials and administrative officials. In the DCS each official, whether correctional or professional correctional officials, regardless of his/her post, is regarded as a rehabilitator.

It was the premise of the study that by determining the relationship between rehabilitation, unit management, rehabilitation needs of offenders and the required skills and tools needed by correctional and professional correctional officials, service delivery in the DCS could be optimised through unit management. The interaction between rehabilitation and unit management is confirmed by Stinchcomb (2011:235), who describes unit management not as a treatment programme or a custodial strategy, but rather as a system whereby custody and treatment work hand in hand within a setting that promotes their close cooperation. Singh (2004:442) contends that one of the primary missions of corrections is to develop and operate correctional programmes that balance the concepts of deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation for individuals in correctional facilities, and unit management provides this balance. Unit management can therefore be seen as the vehicle for the rehabilitation of offenders and orderly prison management in correctional facilities. The system of unit management therefore allows for security and rehabilitation to take place, since it provides a secure structure for safe detention of offenders as well as the practical possibility of engaging offenders easily in rehabilitation programmes whilst still in a secure environment.

The implementation of unit management, rehabilitation and the ORP, however, poses a number of challenges such as high caseloads, overcrowding, and a lack of human resources, infrastructure and facilities. The continual shortage of correctional officials in the DCS and a desperate shortage of professional officials make it difficult for DCS to function at an optimal level and achieve its rehabilitation goals. The ORP requires that all personnel need to be orientated and retrained on the ORP, that the new approach of the ORP be marketed to offenders, that its implementation be monitored and evaluated, and external partnerships strengthened to promote corrections as a societal responsibility (DCS Offender Rehabilitation Path: Presentation to the Portfolio Committee, 2006:16). It was the assumption of this research study that the advantages of unit management outweigh challenges incurred, and should therefore be regarded as a priority in the DCS.

METHODOLOGY

Mixed methods research was the appropriate approach for the study as it is a method that focuses on both qualitative and quantitative research, drawing on the strengths and minimising the limitations of both these approaches (Creswell, 2014:218; Landrum & Gaza, 2015:205). Mixed methods research enriches contextualisation of information and contributes to a broader understanding of the research phenomena, which in the case of the study refers to DCS and specifically sentenced offenders and correctional officials (Westmarland, 2011:108). Louw (2013:9) followed a similar research approach in a study in the Department of Correctional Services on parole violations. The quantitative part of the research study focused on how rehabilitation and unit management could be optimised in the Bethal Management Area, based on the offenders' views on and perceptions of their rehabilitation needs. The qualitative part of the study concentrated on correctional and professional correctional officials' contributions concerning their role in rehabilitation and unit management in the DCS. The research type was applied with a component of basic research (Dantzker & Hunter, 2012:10; Gravetter & Forzano, 2012:43). It was not concerned with solving the immediate problems encountered with rehabilitation in service delivery, but rather building on the little existing knowledge (Fouché & De Vos, 2011:94) of rehabilitation and unit management at the four units in the Bethal Management Area.

The convergent parallel mixed method design (Creswell, 2014:219) was utilised in this study where the researcher collected both quantitative and qualitative data and then integrated the information in the interpretation of the overall results in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem (Creswell, 2014:15). The stratified random sampling method was used in the quantitative study (Frankel, 2010:98; Gravetter & Forzano, 2012:147) in order to select 544 sentenced offenders from the different centres in the Bethal Management Area, comprising Bethal, Standerton, Piet Retief and Volksrust as well as various crime categories. Only male offenders participated in the study, because prison populations in South Africa are generally male dominant (Judicial Inspectorate Annual report, 2016:44) and all the centres in the Bethal Management Area accommodate male offenders only, except for Bethal Centre where there is a female section in the centre. For the qualitative study non-probability purposive sampling was used because the researcher used her own judgement (Bachman & Schutt, 2012:121) to select a total number of 133 correctional and professional correctional officials.

A similar secondary study was done after time elapsed since the primary study. A secondary database assists the researcher to come "to a clearer sense of what is in your data as you have moved forward on your project may give new meanings and understandings to works in the literature that you had previously understood differently or dismissed" (Rosenblatt, 2016:29). In both studies quantitative data were gathered from sentenced male offenders through a survey by means of an administered questionnaire that consisted of open- and closed-ended questions (Alston & Bowles, 2003). The case study was applicable to this study as it entailed exploration and description of an individual case (Fouché & Schurink, 2011:321). In order to obtain in-depth information from correctional and professional correctional officials from the Bethal Management Area, one-on-one interviews were conducted, which were guided by a semi-structured interview schedule (Creswell, 2014:187).

In analysing the quantitative research data, the researcher used the data analysis presented by Fouché and Bartley (2011:252), which includes data preparation, data entry, processing, analysis and interpretation. The qualitative data used the process of data analysis as set out by Schurink, Fouché and De Vos (2011:403), namely preparing and dividing the data; reducing the data; and visualising, representing and displaying the data. Trustworthiness of data was established when the researcher assured participants of her credibility, ensured prolonged engagements at the correctional centres, implemented purposive sampling, recorded all procedures followed in a codebook, created rich data through detailed descriptions of themes, and presented results having objectivity in mind (cf. Lietz & Zayas, 2010:191; Schurink et al., 2011:419). The study was ethically cleared by the University of Pretoria.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Biographical particulars of sentenced offenders

The biographical information assisted the researcher to contextualise the participants' responses within the prison environment. It furthermore assisted in the identification of criminogenic factors, as is described in the rehabilitation model. The research findings show that the highest age group of participants (n=233/42.83%) in the study was between the ages of 22 to 29 years. It is confirmed in the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services: Annual report (2011:12) that 25% of the inmate population in South Africa is between the ages of 21 to 25 years and that 8% of the offenders are between the ages of 18 to 21 years. This implies that a third of the inmate population in South Africa is younger than 25 years of age. Concerning marital status and number of biological children, the majority of the respondents (n=302/55.51%) who participated in this study were single; however, a large group of offenders (n=209/38.41%) were in a relationship with a partner, either in a living-together arrangement or in a marriage, be it customary or lawfully. The findings indicate that of the 544 respondents who participated, 22.97% (n=125) had no children and that the majority of respondents (n=419) 77.02% were fathers to at least one child. The majority (n=279/51.28%) of the respondents' home language was isiZulu. As mentioned by Hagan (2010:399), crime is linked to level of education. It became evident in the Bethal Management Area (sum of respective centres) that most respondents (n=420/77.20%) in this study have an education level which is lower than Grade 12.

Biographical particulars of correctional and professional correctional officials

The majority of the correctional officials from all the centres who participated in this study were males, namely 101/133 (75.93%) while 32/133 (24.06%) were females. The majority of the participants, 63/133 (47.36%), spoke isiZulu as a home language. Even though the majority of participants, namely 79/133 (59.39%), have an education level of a Grade 12 qualification, there was a large group, 47/133 (35.33%) holding a tertiary qualification. The largest number of correctional officials in all the different centres that participated in this study were in the age group of 34 to 41 years, with a total number of 58/133 (43.60%), while 25/133 (18.79%) were between 26 to 33 years of age and 26/133 (19.54%) were in the age group of 42 to 49 years. Only 1/133 (0.75%) official was between 18 and 25 years; and 22/16.53 were 50 and older.

Themes

In this section the themes that were identified from integrated quantitative and qualitative data will be presented and discussed in comparison with other studies. The participants' views are indicated as PP in the case of the primary study and SP in the case of the secondary study.

Theme 1: The concept of rehabilitation in the offenders' understanding

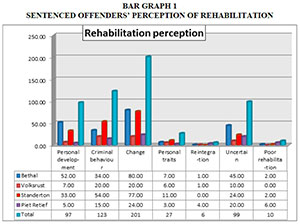

Bar graph 1 below indicates that rehabilitation was understood by offenders as enhancing personal development (n=97) 17.83%, correcting criminal behaviour (n=123) 22.61%, process of change (n=201) 36.94%, improving personal traits (n=27) 4.96%, and re-integration (n=6) 1.10%. However, a small number of respondents, namely (n=10) 1.83%, understood and described rehabilitation broadly and vaguely, and (n=99) 18.19% indicated that they were uncertain about what rehabilitation entails.

Bar graph 1 - Click to enlarge

The graph indicates that there are offenders who associate rehabilitation with changing behaviour, and correcting their mistakes that led to criminal behaviour. A number of offenders do not have a full understanding of what the term rehabilitation entails and are not aware of their own responsibility in their rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is achieved through interventions in order to change attitudes, behaviour and social circumstances (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:76). This study found that offenders were not always sure what was expected from them in terms of their own rehabilitation. The rehabilitation model emphasises that crime is caused by the offender's circumstances, and that when these circumstances or needs have been identified and addressed, the offender should be rehabilitated (Cullen & Jonson, 2012:25). It is important for the offender to understand his own rehabilitation, in order to know where to start with the process of identifying his needs.

Findings indicate that offenders do experience change while serving their sentences; some participants (n=503/92.46%) were of the opinion that their bad behaviour had changed, while others (n=32/5.88%) said that they have not experienced any personal change since they had been sentenced. The researcher's experience is that the rehabilitative effect of imprisonment depends on the individual offender. If an offender is open to rehabilitation and change, and attempts to improve his self-development, it is more likely that he would change. Findings indicated that offenders who changed positively were encouraged by their future plans, which included their families, businesses, studies and having constructive relationships.

Theme 2: The concept of rehabilitation in the officials' understanding

Officials had different viewpoints on what rehabilitation entails. The most prominent views relate to officials' attitudes towards offenders and rehabilitation. As indicated by the following quotes, some officials regard rehabilitation as changing the offender from somebody who can be described in a negative way such as 'bad', 'criminal' or 'exhibiting offending behaviour' to somebody positive, for example 'good', 'law-abiding citizen', or 'displaying acceptable behaviour'.

"I regard it as a way where a person needs to change his bad behaviour to an acceptable behaviour in the community [behaviour acceptable to the community]." PP10

"It is fixing an offender's criminal behaviour whilst incarcerated to promote change and to be able to reinstate him or her back in society as a law-abiding citizen." SP1

Walsh and Hemmens (2011:77) explain that, according to the rational choice theory, offenders decide when to commit crime: "[H]umans have the capacity to make choices and the moral responsibility to make moral choices regardless of the internal or external constraints on one's ability to do so." It gives the impression that when an offender is admitted to a correctional centre, he can be easily perceived by officials as someone with negative, bad, or criminal behaviour, because it was his decision to commit crime and therefore he must face the consequences. This negative perception of offenders might hinder the process of rehabilitation, since it can become difficult at a later stage to remove the negative label assigned to an offender upon admission to a correctional centre. The lack of skills and knowledge on the side of officials aggravates the situation, because they do not realise that the principles of the same rational choice theory can form the basis for officials to equip offenders with improved decision-making skills, and therefore contribute towards their rehabilitation. A number of studies found that the strength of the relationship between staff and the client has an impact on retention and criminal behaviour after treatment (Latessa, Listwan & Koetzle, 2014:104). This emphasises the importance of a good relationship between officials and offenders; but officials harbouring a negative feeling about the offender after admission will influence all rehabilitation efforts.

For many officials, rehabilitation in the DCS meant sending a better person back into the community. They regard it as their role to prepare an offender for his release and that this will be evident when the offender exhibits improved or better behaviour by the time he needs to be released from a correctional centre. One official's view summarises this approach:

"I regard it as a tool that makes offenders better people when released." SP9

Rehabilitation becomes easier when an offender has someone or something that motivates or inspires him to rehabilitate. External factors that serve as motivation, such as family, loved ones, community members, and seeing a future for themselves can contribute to the success of rehabilitation. Maruna and Immarigeon (2004:238) confirm that apart from programme involvement, the rehabilitation of offenders relies heavily on their bonding life circumstances such as a marriage, relationships and employment.

Pointing out the mistakes and/or wrong behaviour of the offender in order to create insight and awareness might be a negative start to the offender's road to rehabilitation. According to the findings, some officials regard rehabilitation as the process where the wrong behaviour and mistakes made by the offender should be pointed out in order to develop insight and an understanding of his actions. Rehabilitation means:

"That an offender understands what he did wrong and don't commit crimes again, to go back to society to work hard to achieve something." SP22

"Making prisoners to realise the wrongs they did and to acquire [equip] them with skills." PP24

This perception focuses on the negative behaviour of the offender, which he needs to be reminded of time and again. In most instances the offender is aware of his behaviour and knows the reason for his incarceration. The strength-based approach states that the focus should rather be on the strengths of the offender in order to maintain a positive experience that would probably yield better results (Saleebey, 2013:20). Focusing on strengths would be less of a threatening experience for the offender, and it could minimise resistance and increase cooperation.

Findings revealed that some officials felt negative about the concept of rehabilitation as the following statements show:

"It is not correctly implemented and wasn't thoroughly researched. It has a good place to helping inmates become law-abiding citizens if correctly implemented and if thoroughly researched." PP3

"It's a mess because 98% of offenders taken to do courses, always come back to prison after some couple of months and they always steal at the prison." PP7

For rehabilitation to be implemented successfully, the correctional and professional correctional officials should believe in its value and worth. Officials' negative attitudes towards rehabilitation could easily be transferred to offenders, who will adopt the same attitude. According to Latessa et al. (2014:103), the attitudes of officials determine the success they have with effective rehabilitation programmes, as is evident from their statement that, "In particular, those who were warm, non-confrontational, empathetic and directive were more effective". Louw (2013:209) found in his study conducted with sentenced offenders that the majority of the participants were of the opinion that correctional officials were not rehabilitators.

If correctional and professional officials are expected to rehabilitate offenders, they should be aware of what rehabilitation entails and what they should actually do to be able to reach such a goal. The White Paper on Corrections in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:21) introduced the concept of rehabilitation during 2005 when it was launched. It has been twelve years since the introduction of rehabilitation in correctional centres, and findings indicate that there are still officials who do not have a clear understanding of rehabilitation, or who are negative about the implementation or effectiveness of rehabilitation.

Findings indicate some commonalities in the views of officials and offenders on the concept rehabilitation. They may know the concept but not be familiar with what it entails; others see it as a process of change to correct the mistakes that led to committing the crime. Furthermore, neither offenders nor officials have a clear understanding of what their responsibilities are in the rehabilitation process and hence some are negative about rehabilitation. In addition, officials easily label an offender in a negative way and treat him accordingly, which undermines their role as rehabilitator.

Theme 3: Rehabilitation needs of offenders and the necessary skills and tools needed by officials to optimise rehabilitation

Offenders were able to identify and voice their basic rehabilitation needs in order to optimise rehabilitation. Findings revealed that vocational skills training (32.53%, n=177) is the top priority rehabilitation need of offenders, followed by better education and educational resources (22.24%, n=121), rehabilitation programmes (social work and spiritual care programmes) (20.40%, n=111), personal intervention in the form of individual counselling (6.43%, n=35) and recreational activities (8.08%, n=44). Although vocational training was identified as the priority need by both offenders and officials, most of the respondents did not participate in any of the vocational training activities in the Bethal Management Area. In a study on offenders in Gauteng province, Louw (2013:157) found that the majority of offenders did not attend any vocational training. Four years later this finding is confirmed in the current study, which indicates that there was little progress made by the DCS concerning the provision of vocational skills training to offenders. Findings show that some offenders have a desire to develop themselves, but because these opportunities are currently lacking in that they are either unavailable at certain centres in the Bethal Management Area or where they are available, the variety of skills is limited. The lack of vocational skills leads to the DCS failing in rehabilitating offenders fully.

In order to meet the rehabilitation needs of offenders, all officials should be equipped with the necessary skills, 'tools' and knowledge to present rehabilitation programmes. In this study officials indicated that they needed to be equipped with the necessary skills and 'tools' to improve offender rehabilitation, which could be acquired by attending specialised courses. Officials indicated that they in general feel incompetent and unprofessional when dealing with the rehabilitation issues of offenders. Most of them are in possession of a Grade 12 qualification and need specialised training in order to meet the needs of the offenders in a knowledgeable and professional manner. Even though professional correctional officials, which includes social workers, nurses and educationists, are trained in their field of specialisation, specific training is needed in terms of offender rehabilitation. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that DCS experiences a shortage of correctional and professional correctional officials. It is revealed in the DCS Annual Report (2016:94) that even though 1,055 correctional officials were appointed and transferred into the DCS, during the 2015/2016 financial year 1,243 correctional officials terminated their service or were transferred out of the DCS. This scenario negatively influences the achievement of rehabilitation goals.

Officials indicated that the equipment, materials and resources that they needed to improve offender rehabilitation were seriously lacking. They are expected to function as rehabilitators despite having insufficient equipment such as computers, telephones, materials, stationery and resources, including funding. This not only gives an impression of lack of professionalism, but it is also demotivating to the officials. Findings further indicated that the design and infrastructure of correctional centres hinder offender rehabilitation. The plans according to which correctional centres were built many years ago focused more on the punitive aspect of imprisonment. Later, when rehabilitation was introduced into the DCS, the challenges created by the infrastructure surfaced. It was then realised that the correctional centre structure does not allow for offices for professionals: there are no decentralised units for unit management, no group work or programme rooms, no classrooms for the school section, and insufficient space for the health care section. It happens that professionals who are supposed to rehabilitate offenders have to make use of spaces that are converted into offices - resulting in an uncomfortable working environment and experience. As long as the DCS does not succeed in providing correctional officials with a working environment conducive to the rehabilitation of offenders, rehabilitation will remain a challenge irrespective of whether offender identified and conveyed their rehabilitation needs.

Theme 4: Offenders' and officials' perceptions of unit management and implementation

Findings revealed that unit management was a term unknown to offenders, since (n=518) 95.22% of respondents were unable to define it correctly, which implies that they were unaware that it is implemented in the centres where they are accommodated. Likewise, some officials were unfamiliar with the concept and were, in most cases, not able to define or describe unit management correctly. However, the majority of the officials felt negative about unit management because of all the associated challenges, and ultimately because of the failure to implement it properly. They were also confused about their roles with regard to unit management and rehabilitation. Officials were of the opinion that the shortage of human resources and the lack of resources in general, as well as inadequate infrastructure, make it impossible to put unit management into operation, as is evident from some of their perceptions, for example:

"It is a brilliant concept; however, it needs more training of officials working in units. It needs more manpower [sic]to be allocated into units." PP11

"We need more officials to address the ratio. We need specialists in development of offenders. Our correctional structure should be changed for housing units. We need a unit manager in each section." SP18

"Unfortunately it's something that is too farfetched - the buildings. We are still utilising the structure which was designed for locking ... feeding ... locking." SP20

In order for unit management to function fully, officials further indicated that properly trained correctional officers should be appointed, and that the development and design of facilities and infrastructure should be improved in order to accommodate rehabilitation and unit management.

Furthermore, more professional personnel should be appointed; vocational training should be provided to offenders in order to ensure their rehabilitation; and finally, the wellbeing of the officials, and not only the offenders, should be prioritised.

Rehabilitation and unit management complement each other when both are fully implemented, as stated in The White Paper on Corrections in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:88): "unit management is the desired method of correctional centre management and an effective method to facilitate restorative rehabilitation". The current situation in the DCS, however, is that neither rehabilitation nor unit management is implemented successfully and, given the nature of the challenges and hindrances indicated by this study, the future of both rehabilitation and unit management in DCS is questionable. In turn, the ineffective implementation of unit management implies that rehabilitation of offenders is compromised.

In summary, most of the offenders are unfamiliar with certain elements of unit management such as decentralised units, structured day programmes, case files, unit manager, case management supervisor and case officer. Offenders are probably not aware of these elements of unit management, because it is not implemented or functional in their correctional centres because of the officials' lack of understanding of the concept themselves. Though officials are aware of unit management and its elements, they do not have a clear understanding of what it entails, and mostly see unit management in a negative light because of all the challenges associated with it. This results in the entire concept of unit management being fruitless for both offenders and officials and hence it will require a serious effort from the DCS to implement it fully in the Bethal Management Area.

CONCLUSION

The starting point in optimising rehabilitation and unit management is information, knowledge and resources to prepare and equip officials to function as rehabilitators and ensure successful rehabilitation in the DCS. Furthermore, being equipped will motivate officials and develop optimism amongst them concerning rehabilitation and unit management. Therefore, the DCS needs to equip its officials through the necessary training on the rehabilitation of offenders and unit management, and follow through with continued training. The provision of financial and human resources, as well as the appointment of professional personnel, should be prioritised by the DCS to start the unit management process.

Criminogenic factors should be addressed during the time that the offender serves his sentence in order to enhance the rehabilitation process. When these factors are left unattended, it increases the risk factors for offenders that can lead to recidivism. The assessment phase in the ORP is therefore crucial, since it is the period during which time the offender's criminogenic factors should be identified by the CAO, and referred to the relevant officials for appropriate action. The criminogenic factors should thus guide the CAO and all other officials involved in the correctional sentence plan (CSP) concerning the scheduling and referring of the offender for necessary intervention. The rehabilitation model, according to Raynor and Robinson (2005:5), "assumes that positive change can be brought about by subjecting offenders to particular interventions, programmes: with the right intervention, offenders can be brought into line with a law-abiding norm."

Officials who have only a rudimentary understanding of rehabilitation will find it difficult, if not impossible, to lead offenders who are just as ignorant, in their rehabilitation processes. When offenders are admitted to a correctional centre, they normally experience anxiety because of the unknown and unfamiliar circumstances that they find themselves in. It might be that surviving incarceration is prioritised above rehabilitation by the offender during his adaptation period in the orientation stage. However, it is the responsibility of the officials to familiarise the offender with rehabilitation and unit management and to guide them in their rehabilitation process. During the orientation phase officials need to exhibit a positive attitude of an inspiring nature, since it is the first contact that the offender has with his rehabilitation - it is the starting point of the offender's journey to rehabilitation. If the official does not inspire offenders regarding their rehabilitation process, it is more likely that the offender would also develop a negative attitude towards corrections in general.

DCS has a responsibility to take certain measures and put certain factors in place before the vision and mission of the DCS can be fulfilled. Correctional and professional correctional officials cannot be expected to function as rehabilitators as stated in The White Paper on Corrections in SA (Republic of South Africa, Ministry for Correctional Services, 2005:114) when the means for doing so are not available. The shortage of human resources, for instance, has a direct impact on rehabilitation and unit management, because without officials the posts cannot be filled and the work cannot be done. The shortage of professional correctional officials impacts on the presentation of programmes in that some of the programmes are not available, and decentralisation within the framework of unit management requires that a correctional centre be divided into different housing units. If the design and infrastructure of the correctional centre do not allow for this, the practical implementation of unit management cannot be reached.

The available officials in the DCS can be regarded as ineffective in their rehabilitation of offenders, despite their efforts, because of a lack of the specific skills and 'tools' that they require. If the DCS wants to create the ideal profile for the ideal correctional official, as discussed in Chapter 8 of The White Paper on Corrections in SA, (Republic of South Africa, Ministry of Correctional Services, 2005) as opposed to the current profile, attention should be given to the development of these officials in terms of training, tertiary qualifications, provision of resources and materials, including training on new ventures in DCS.

REFERENCES

ALSTON, M. & BOWLES, W. 2003. Research for social workers: An introduction to methods. (2nded). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

BACHMAN, R. & SCHUTT, R.K. 2011. The practise of research in criminology and criminal justice. (4th ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

BIRZER, M.L. & ROBERSON, C. 2004. Introduction to corrections. (2nd ed). Nevada: Copperhouse Publishing Company. [ Links ]

BRUYNS, H.J. 2007. The impact of prison reform on the inmate population of Swaziland. Unpublished Doctor of Literature and Philosophy thesis. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

CORRECTIONAL SERVICES ACT 111 OF 1998 (Published in the Government Gazette, (19522) Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (4th ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2015. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

CULLEN, F.T. & JONSON, C.L. 2012. Correctional theory: Context and consequences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

DANTZKER, M.L. & HUNTER, R. D. 2012. Research methods for criminology and criminal justice. (3rd ed). Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. 2016. Annual report 2015/2016. Pretoria: Department of Correctional Services. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. 2007. Offender Rehabilitation Path. Orientation Guide. Pretoria [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES: Offender Rehabilitation Path: Presentation to the Portfolio Committee. 2007. Pretoria [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. 2010. Strategic plan for 2010/2011-2013/2014. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. [Sa] Unit Management Policy. Pretoria. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & BARTLEY, A. 2011. Quantitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human science professions. (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Formal formulations. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human science professions. (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds). Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human science professions. (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

FRANKEL, M. 2010. Sampling theory. In MARSDEN, P.V. & WRIGHT, J.D. (eds). Handbook of survey research. (2nd ed). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

GRAVETTER, F.J. & FORZANO, A.B. 2012. Research methods for the Behavioural sciences. (4th ed). USA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

HAGAN, F. E. 2010. Crime types and criminals. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication, Inc. [ Links ]

JUDICIAL INSPECTORATE FOR CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. 2011. Annual report 2010/2011 Financial Year. Cape Town: Government Printers. [ Links ]

JUDICIAL INSPECTORATE FOR CORRECTIONAL SERVICES. 2016. Annual report 2015/2016 Financial Year. Cape Town: Government Printers. [ Links ]

LANDRUM, B. & GARZA, G. 2015. Mending fences: Defining the domains and approaches of quantitative and qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2): 199-209. [ Links ]

LATESSA, E.J., LISTWAN, S.J. & KOETZLE, D. 2014. What works (and doesn't) in reducing recidivism. Oxford: Routledge. [ Links ]

LIETZ, C.A. & ZAYAS, L.E. 2010. Evaluating qualitative research for social work practitioners. Advances in Social Work. 11(2):188-202. [ Links ]

LOUW, F.C.M. 2013. A mixed methods research study on parole violations in South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (DPhil Thesis) [ Links ]

MARUNA, S. & IMMARIGEON, R. 2004. After crime and punishment: pathways to offenderre integration. Devon: Willan Publishing. [ Links ]

MOHAJANE, J. 1998. It's a call for people first. Nexus, November: 8-10. [ Links ]

RAYNOR, P. & ROBINSON, G. 2005. Rehabilitation, Crime and Justice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2005. Ministry for Correctional Services. The White Paper on Corrections in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

ROSENBLATT, P.C. 2016. Restarting stalled research. London: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

SALEEBEY, D. 2013. The Strengths perspective in social work practice. (6th ed). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds). Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human science professions. (4thed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

SINGH, S. 2004. Prison overcrowding: A Penological perspective. Pretoria: UNISA. (DPhil Thesis) [ Links ]

SINGH, S. 2005. The historical development in prisons in South Africa: A penological perspective. New Contree. 50:15-38. [ Links ]

STINCHCOMB, J.B. 2011. Corrections: Foundations for the future. (2nd ed). Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

WALSH, A. & HEMMENS, C. 2011. Introduction to criminology: A text/reader. (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

WESTMARLAND, L. 2011. Researching crime and justice: Tales from the field. Oxford: Routledge. [ Links ]