Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.54 n.4 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/54-4-673

ARTICLES

Parents' experiences of parenting an adolescent abusing substances

Aziza Kalam; Thuli Godfrey Mthembu

Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Adolescent substance abuse is one of the social and public health concerns that appears to influence parenting, but little is known about the parents' experiences of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances. An exploratory, descriptive, qualitative approach was employed with in-depth interviews to explore the parents' experiences of parenting adolescents abusing substances. Thematically analysed data produced three themes: parenting my way, perceived barriers and facilitating factors. Authoritarian, authoritative and permissive parenting styles were discussed to create a supportive environment to enhance parents' coping strategies. This work contributes to existing knowledge on parents dealing with adolescent substance abuse by providing strategies to enhance parenting.

INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

Adolescent substance abuse is one of the most significant current discussions in social and public health (Wegner & Flisher, 2009). According to the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU), it has been reported that in South Africa between 17% (Northern Region) and 50% (Central Region) of patients in treatment use alcohol as a primary drug of abuse (Dada & Harker Burnhams, 2017). In relation to adolescent substance abuse, it was found that between 1% (Eastern Cape) and 11% (Western Cape and Northern Region) of patients who were under the age of indicated that alcohol was their primary substance of abuse. The Department of Social Development (2017) reports that youths and their parents appeared to be severely affected by the adolescents' use of harmful substances. Research indicates that the experiences of parents of adolescents with substance abuse problems are a neglected topic of inquiry worldwide and particularly in South Africa (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017).

LITERATURE REVIEW

The reviewed literature focuses on parenting as an important element of family life. The focus is on the effects of adolescent substance abuse on parents' wellbeing, especially mothers' coping experiences in dealing with adolescents involved in substance abuse.

Parenting is an important component in the family system and plays a key role in engaging children in assuming diverse and complementary responsibilities (Bornstein, 2001). Parents are expected to meet the biological, physical, financial and health needs of their children (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017). Parents are perceived as enablers who provide children with opportunities and space to engage in meaningful and purposeful activities and relationships as part of their learning. However, parents are sometimes faced with considerable challenges in their parenting experiences.

Previous studies have reported that larger social systems including family configuration, support systems, community ties as well as work and social, educational and economic class tend to influence the nature of parenting (Bornstein, 2001). However, research has consistently shown that parenting is affected by anxiety, as well as the stresses and disappointments related to unhealthy adolescent behaviours such as substance abuse, high-risk sexual behaviour and interpersonal violence (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017; Cook, Spinazzola, Ford, Lanktree, Blaustein, Cloitre, Derosa, Hubbard, Kagan, Liautaud, Mallah, Olafson. & Van der Kolk, 2005). The parent-adolescent relationship seems to be fraught with challenges that might influence an adolescent's cognitive, social and emotional functioning in families and communities (Moretti & Peled, 2004; Bornstein, 2001).

Family systems theory postulates that all family members need each other in times of joy as well as difficulties in life. Regarding adolescent substance abuse and families, it is clear that the whole family's wellbeing is affected by the behaviour of one family member abusing substances (Kühn & Slabbert, 2017). Family systems are comprised of three subsystems which include the couple, parent-child and siblings. The focus of the current study is the parent-child subsystem and adolescent substance abuse, because little has been done in this area (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017). There is a large volume of published studies describing the effects of adolescent substance abuse on the wellbeing of individuals, families, societies and communities (Department of Social Development, 2017; Tshitangano & Tosin, 2016; Visser & Routledge, 2007). The emotional and psychological impacts of adolescent substance abuse resulted in social ills developing among families and communities (Department of Social Development, 2017). It has been suggested that 'a combination of environmental and individual factors need to be dealt with order to combat substance abuse in communities (Department of Social Development, 2017: 45). Furthermore, better parenting has been identified as a major priority that needs to be tackled to enable community members to combat substance abuse. However, there is paucity of information regarding parents' experiences of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances.

There are a quite few research studies on mothers' experiences of coping with adolescent substance abuse (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017; Wegner, Arend, Bassadien, Bismath & Cros, 2014). Previous research has shown that mothers' coping responses to adolescent substance abuse seemed to be characterised by a variety of complexities (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017; Wegner et al., 2014). The study by Wegner et al., (2014) explored how the occupational performance patterns (roles, rituals, routines and habits) of mothers were influenced by the addictive behaviours of their drug-dependent, young adult children. That study therefore provided an insight into the occupational challenges experienced by mothers of drug-dependent youths. However, studies on the experience of the parents themselves who are parenting adolescents abusing substances are rare in the literature.

Although there were studies on coping experiences and adolescent substance abuse, few of them focused on the experiences of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances. Studies have been conducted on the adolescents who abused substances in the Western Cape, South Africa. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct research on the parents of such adolescents, because they are faced with a multitude of stresses that may potentially have a profound impact on their psychological wellbeing (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2013). Consequently, a question has been raised about the parents' experiences of parenting an adolescent who abuse substances. Understanding these parents' experiences may contribute towards gaining an insight into how they cope with the stresses involved. This study is guided by the research question: What are the parents' experiences of parenting an adolescent who abuses substances?

RESEARCH GOAL

The goal of the study was to explore the parents' experiences of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research method was used to gain insight into and understanding of the parents' experiences as an important aspect of their human and social interactions. Qualitative methods offer an effective way of understanding how the participants make sense of and interpret their thoughts, feelings and social life (Sutton & Austin, 2015). Therefore, this study employed exploratory and descriptive research approaches. According to Van Wyk (2012), an explorative approach provides insight into the uncertainty associated with experiences and into a problem that is not very well understood, like the parents' experiences of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances. The descriptive approach was used to accurately capture and describe the parents' experiences (Van Wyk, 2012).

The participants were recruited through a rehabilitation centre where their children were admitted. This facility provided treatment for individuals who were recovering from their drug addiction. In this study a purposive sampling method was used to recruit four participants who were knowledgeable about their experiences of parenting adolescents abusing substances (Dolores & Tongco, 2007). The study included four parents of adolescents between the ages of 12 - 18 years, male and female, who were admitted on a voluntary and involuntary basis, or had been admitted through the court because of substance abuse, and were attending the rehabilitation centre.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews using the interview guide. According to LewisBeck, Bryman and Futting Liao (2004), semi-structured interviews allow the participants to share their experiences - in this case, of parenting - until data saturation was reached. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim in preparation for data analysis. Six phases of thematic analysis were used in this study as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Phase one is familiarisation through reading the transcripts several times to make sense of the data in preparation for coding. Phase two entails creating initial codes, which are the most basic segments of the information that gives it meaning. Phase three involves searching for themes as part of the process of analysis that combines different codes into overarching themes. In phase four the refinement and reviewing of these themes is undertaken to ensure that they make sense. Phase five is the process of defining and naming the themes after the four researchers are satisfied with their thematic map sketched in phase four. Lastly, phase six is producing a report of the analysis of the findings, so that it produces a coherent and interesting account within and across the themes.

Trustworthiness was ensured through the use of triangulation (Krefting, 1991) by using data sources which include parents and a key informant. Member checking was used in order to validate the findings of the study with the participants. Reflexivity was enhanced by each researcher disclosing their personal feelings regarding the topic of the research. An audit trail was used from the beginning until the end of the study in order to monitor the progress of the study. Peer debriefing was used to discuss the process of the study and analysis processes.

Ethical approval was sought from the University of the Western Cape's Senate Research Committee as well as the rehabilitation centre. Ethical clearance was obtained (Protocol number: 14/6/60). Four participants volunteered to be part of the study and gave their written consent. The participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without repercussions. Anonymity was ensured by providing participants with a number in order to protect their privacy and ensure confidentiality.

Limitations: This study was conducted with only four participants from the community. Therefore, the findings of the study cannot be generalised to all parents living with adolescent who are abusing substances. Another limitation of this study is that it was conducted with single parents, meaning the father-figure was absent.

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This section of the paper presents the participants' socio-demographic information and themes together with their categories, with a literature control.

PARTICIPANTS' SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

Four female participants were recruited with the assistance of the rehabilitation centre that offers services to community members living with adolescents who are abusing substances. Regarding marital status, all participants indicated that they were single parent, living in a low socio-economic status (Table 1).

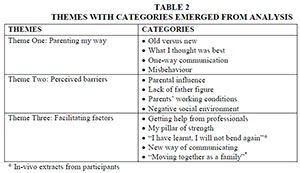

Three themes with 13 categories that emerged from the thematically analysed data are displayed in Table 2 below.

Theme One: Parenting my way

This theme describes how the parents perceived their parenting styles in order to manage their adolescents who abuse substances within the home environment. The parents compared the new styles compared to the styles that were used in their families while they were growing up. The first theme highlights the diverse styles which appeared to be the best for them. This theme also captures what they thought they knew best about communication and misbehaviour.

Old versus new

A majority of the participants indicated that grandparents raised them because their own parents seemed to abuse substances. The participants further shared that their own parents were unable to fulfil the parental role. As a result, the participants mentioned that they did not wish to raise their children in the same way; therefore, they opted to raise their children in a different way.

"She's totally different from my mom. Say, for instance, my father was a drug addict and my mom is drinking... So for me it was, I don't want to be like my mother, don't wanna be like my father and I want to be like my grandma." (Participant 3)

"I never grew up my, with both my parents, I'm a grannie's child." (Participant 2)

According to Bandura (2011), social learning involves learning new patterns of behaviour through interaction with others. The participants had an opportunity to learn from their grandparents, which was a positive experience for them, as part of intergenerational learning. This is contrary to the experiences of the participants in the present study, as one participant commented that they did not learn anything about parenting skills from their biological parents.

"Ek het nie parenting skills nie, my ma het vir my niks geleer nie." (Participant 4)

[I don't have parenting skills, my mother did not teach me any]

What I thought was best

In relation to what I thought was the best, the participants shared that they incorporated some authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles and their strategies to handle their adolescent's behaviour. Oburu and Palmérus (2003) explain that discipline strategies like slapping, hitting and beating tend to be related to the stress experienced as part of parenting. This was supported by the participants' reports that they disciplined the adolescent if they were not complying with family rules.

"I did give him a hiding and things like that, if I say you can't go there, you can't go there..." (Participant 1)

"It doesn't matter where he is...and I phone and he must answer the phone, that is how strict I am and if he doesn't answer the phone he knows the consequences." (Participant 3)

The above findings are consistent with an authoritarian parenting style whereby parents appeared to compel obedience through punitive and restrictive strategies. Conversely, some participants shared their experiences related to authoritative parenting style, which assisted them to balance being strict and being tolerant. This kind of parenting style assisted the participants to share warmth, support their adolescent, and promote prosocial behaviour. Previous studies have indicated that an authoritative parenting style seemed to enhance confidence (Baumrid, 1991). Therefore, one of the participants mentioned taking some time to understand the adolescents' perspectives regarding their behaviour.

"No I don't use, I don't hit. I sit down and I talk softly, I don't scream and I don't shout. It's just that, you know you gotta understand me and I have to understand you. If you have a problem, be open with me." (Participant 2)

From the participants' experiences, it was evident that a permissive parenting style was predominantly used within families with adolescents who abused substances. According to Baumrid (1991), permissive parents tend to be more responsive than demanding. They were lenient and allowed their children to practise self-regulation. However, it can be difficult for the parents who use a permissive parenting style to manage their children who engage in unhealthy behaviours, because they appeared to avoid confrontation. Consequently, the avoidance of confrontation could increase the parent's stress in parenting their adolescents abusing substances. This can be noted from one of the participants, who said there were no boundaries and rules for the children.

"Permissive parenting style, I find that there was either no clear boundaries ... rules, for the child in place or it was very loose and, what I found within the programme, as we continued the previous programme, parents allowed the children, especially the boundary time, when to come in . it was actually very late and the parents didn't know where the child was and through me guiding them in terms of the actual schedule and also boundaries and rules and discipline.". (Key informant)

One-way communication

Parent-adolescent communication plays an important role in the maintenance of family cohesion and adaptability during situational and developmental stresses (Barnes & Olson, 1985; Olson, 2000). However, the findings of the present research has consistently shown that these parents tried to create a supportive environment for communication, but the adolescents were not keen to share with their parents. This indicates that the participants appeared to be stressed by the one-way communication.

"We sit in my room on a Friday, we sit together and ask how was your week ... no it's fine I was there, I was doing this and that . you see I always talk to them about anything but sometimes they don't open up" (Participant 3)

The issue of family communication was given fresh prominence by many of the participants during the interviews. The participants shared that they struggled to handle the stresses of their adolescent abusing substances. One participant mentioned that

"No there was always aggressiveness, and he started to shout at me things like that, things he never uses to do before and he took stuff here in the house." (Participant 1)

This finding support Barnes and Olson (1985) that lack of communication skills seems to inhibit family cohesion.

Therefore, the evidence from the participants indicated that there was a need for strategies that could be used to mitigate the communication stresses experienced in their families. The role of positive communication was perceived as one of the enablers that the participants felt that they should work on with their children. Another participant made an interesting point about an alternative method such as writing letters to facilitate communication with the adolescents.

"Al way ek vir hom kan reach is om op sy level te kom, en ek skryf hom n brief terug."

[The only way I can reach him is to get onto his level and I will write a letter back to him] (Participant 4)

Misbehaviour

In talking about the adolescents' misbehaviour, the participants shared that they had to use behavioural modification strategies such as withdrawal of privileges and denying them previously granted opportunities. This finding is in agreement with the work of Oburu and Palmérus (2003), who indicated that parents tend to deprive their children of something they would dearly like to do. This was noted from one participant who shared that:

"Doing something wrong ... if they misbehave or, or does not comply, then I just take away their .... you know ... their, monthly spending, whatever they use on a daily basis and cell phones." (Participant 2)

Theme Two: Perceived Barriers

This theme describes a variety of barriers experienced by the participants as part of parenting adolescents who are abusing substances. The perceived barriers included parental influence, lack of support from a father figure, parents' working conditions and negative social environment.

Parental influence

A considerable amount of literature has been published on parents abusing substances and parenting their children. These studies have reported that parental influence in parenting children is an increasingly important area in family functioning (McKeganey, Barnard & McIntosh, 2002). In describing the parental influence in relation to the participants of the present study, it was evident that some of the adolescents were exposed to substance abuse activities within their families. The participants' and key informant's interviews echoed McKeganey et al. (2002), who found that children tend to accompany their parents in the search for drugs and were susceptible to be exposed to the world of drug dealing. This can be noted from the participants' responses as follows:

"Some of the clients' parents are either abusing substances as well. Uhm either the parents but in most cases other family members, brothers or sister or other relatives or extended family." (Key Informant)

Learnt behaviour appeared as an influence in the abuse of substances amongst the adolescents, as reported by the participants. It was noted that some fathers seemed to be role models for the adolescents to abuse substances. This indicates that the participants were disappointed and hurt about the home situations.

"...want sy pa gebruik ook drugs, hy gebruik, hy hy's ook 'n drug addict hy is like a recovery, but he's still using it... "

[Because his father also uses drugs, he uses, he is also a drug addict. He is like in recovery, but he still using it.] (Participant 4)

Lack of father figure

Father involvement is imperative in the development and welfare of their children (Hoskins, 2014; Sarkadi, Kristiansson, Oberklaid & Bremberg, 2007). The involvement of a father in parenting seems to be associated with a reduction of behavioural problems in boys and psychological problems in young women (Sarkadi et al., 2007). Despite the positive evidence by Sarkadi et al. (2007), the participants' responses from the current study show that the lack of a father figure appeared to be an aggravating factor in parenting adolescents who are abusing substances. One of the participants said that:

"He doesn't have that constant; he doesn't have that constant male figure. " (Participant 1)

It is important take note that all the participants were single parents and they had to be stricter in setting boundaries and rules. Consequently, the participants had to play the dual role of being a mother and a father in order to deal with the challenges they were facing in dealing with their children. This is what one participant said:

"But I'm a mother, I'm the mother and the father and they don't think about, they don't ... ja you the father as well." (Participant 3)

Father involvement formed the central focus of a systematic review study by Sarkadi et al. (2007:157) in which the author found that strategies such as inviting fathers to come in for health-care related visits for their infants, and to speak directly to the father as well as the mother, were considered to be effective. Conversely, it was noted from the participants' answers that the fathers of the adolescents were not part of the counselling. Participant 1 shared the frustration of the absence of the father figure during consultation with professionals.

"....Ja because if there is two parents, you know mos, a child will always be scared for one and things like that and the father is a very strict person, you see just like that. When we attend the counselling and other stuff... His father was not part of his life". (Participant 1)

The evidence presented in this finding suggests that there is a need for policies that would promote father involvement and participation in their children's health. Additionally, the finding above supports Sarkadi et al., (2007:157) conception that 'fathers, indeed, have an important role in promoting their child's social and emotional development'.

In their important investigation into mothers' coping experience and adolescent substance abuse, Groenewald and Bhana (2017) found that mothers referred to tolerant coping as part of self-blame for the development of substance abuse. Similarly, there seems to be some evidence to indicate that the participants in our study experienced guilty consciences because they could not figure out in time that their children were using substances. One participant said:

"Vir my is dit I failed him you know I failed him in many ways because I ... ek het nie regtig signs regtig gesien at the beginning nie."

[For me, it is as if I failed him, you know. Ifailed him in many ways, because I did not see the signs in the beginning] (Participant 4)

Parents' working conditions

According to the World Health Organization (2017), working conditions are among the social determinants of health. This indicates that working hours should be considered as important to prevent burnout and ill-health. With respect to the current study, the participants shared that their working conditions seemed to have contributed to their adolescents' abusive behaviour. Menaghan and Parcel (1995) suggest that parental working hours seem to influence the children's home environment and upbringing. It was clear from the participants' demanding and extensive overtime that work affected the quality of the family's social capital. Similarly, the participants felt that loneliness made the adolescents resort to abusing substances, as they had nothing to do at home when they were left alone.

"I think he did started to feeling lonely and stuff like that because I was always gone, always gone, every weekend there was no weekends I don't know about weekends at home, holidays gone." (Participant 1)

Negative social environment

Studies of adolescent substance abuse show the importance of improving our understanding of 'how personal and social contexts influence coping behaviour' in the family (Groenewald & Bhana, 2017: 433). In reflecting on the negative social environment, it appeared that participants' quality of life, health and wellbeing tended to be at risk because of they were parenting adolescents who were abusing substances. It was noted that nearly all the participants were frustrated by the relationships and acquaintances of the adolescents in the community and school environments.

"Yeah; it's just gang-ridden and substances abuses and crime-ridden. Yeah, so it's coming from different areas and at times ...from very difficult circumstances." (Key Informant)

Parent monitoring is defined as 'parental behaviours that regulate and provide awareness of their offspring's whereabouts, conduct and companions' (Hoskins, 2014: 511). The findings indicated that parents observed changes in their adolescent's behaviours, such as being aggressive, not attending class, getting involved in gangsterism and neglecting to take care of themselves.

"He was very aggressive, very demanding ... he wants his way and things got haywire at school, didn't go to school, classes, bunk school. I could see his behaviour changed, he just wants things, then ... it is all the excuses, I must have this and I must have that... and that 's, I could see that he was lacking in himself, you know, self-caring, hygiene andja" (Participant 2)

The literature indicates that parenting an adolescent who abuses substances may be a critical experience for the parents (Wegner et al., 2014). There were times that the adolescents would not come home, which resulted in sleepless nights for the participants. As one participant said:

".beland hy met verkere vriende en toe bevind my kind met tik en toe umm kom glad nie meer huis toe nie."

[He landed up with the wrong friends, then he found tik, and then he did not come home anymore] (Participant 4)

The disturbance in the participants' rest and sleep routine seemed to be a barrier in balancing role expectations related to their living and work conditions. This finding is in agreement with Wegner et al. (2014) that parenting a drug-abusing adolescent has a huge impact on the health and wellbeing of the mothers.

"It is just not, it's not fair on me and my health you know, one tends to get . you tense at work, you tense at home. You can't sleep cause the child's not in at 8 o'clock, its 12 o' clock, midnight ... it's two then, it's you don't even come home, how do you feel, what do you think it made me feel." (Participant 2)

The financial burden is something that the participants were grappling with in their families. The findings of the current study are consistent with those of Wegner et al. (2014), who found that mothers tend to spent more money to bail out their children. The participants shared their frustration at having to replace the stolen items, thus leading to bigger financial strains. The participants further explained that this had become a challenging cycle, leaving them with less control and facing more financial stress.

".dit was tough financially ook."

[It was also tough financially] (Participant 4)

Eventually, the participants expressed feelings of despair because they had invested a lot in the lives of the adolescents abusing substances. Accordingly, the participants felt that the adolescents' unhealthy behaviours manipulated them; hence they felt they had reached a dead-end.

"Ek het net besluit enough is enough, ek help nie my kind nie ".

[I just decided enough is enough. I'm not helping my child] (Participant 4)

Thus, the perceived dilemmas seemed to influence the participants' state of health, family and occupations.

Theme Three: Facilitating factors

This theme captures the facilitators that enabled the participants to perceive life in a positive lens so that they carry on in the mist of difficulties of raising adolescents abusing substances. The facilitators included getting help from professionals as a pillar of strength which will guide them to find new ways of communicating and move together as a family.

Getting Help from professionals

According to Coe (2009), understanding help-seeking attitudes, intentions and behaviours enables health professionals to provide the appropriate services to clients who need psychological support. Nearly all participants indicated that they took the initiative to approach professionals in the rehabilitation centres in order to seek help. The initiatives were perceived as facilitators of collaborative partnership between the participants and the team in the rehabilitation centres. This enabled the participants to find a place that would be able to rehabilitate the adolescents abusing substances. One participant subsequently disclosed:

"I had the counsellor at (rehabilitation centre) that social worker; I had a social worker there." (Participant 2)

Awareness of the contextual issues enabled the participants to use a variety of strategies to seek help for themselves and the adolescents abusing substances. The strategies used to raise their concerns and seek help included the media, the Department of Health, the legal system and starting a petition and removing the adolescent from their environments. Participant 1 shared that she sought help from the "Social worker, so I went to 3rd degree and that lady helped me."

My Pillar of S]strength

A Christian faith-based theory of recovery highlights the importance of acknowledging God's presence during crises like substance abuse (Timmons, 2012). Prayer was perceived as one of the pillars of strength that connected the participants with God for help to cope with the family issues. Participants highlighted that they relied on their religion to enrich their faith, which kept them going while parenting an adolescent abusing substances.

"I just prayed about it and ask people to pray with me through this." (Participant 4)

This finding is consistent with that of Mabe, Dell and Josephson (2011), who indicated that parents tend to seek strength, support and guidance from God in order to manage stressful life events. Some participants perceived good relationships with their friends and community support groups as facilitators of their strength to carry on with life irrespective of the difficulties.

"I've been in counselling, I've been in a support group at school, at... church. " (Participant 2)

The above findings are supported in the literature (Coe, 2009; Wegner et al., 2014) indicating that parents seek help by discussing their problem with their close friends and family.

"I have learnt, I will not bend again"

The heading of this section comes from an interview with the fourth participant who shared that parenting an adolescent abusing substances enabled her to be more assertive and rigid. According to Olson (2000), family adaptability refers to the ability of the family system to reorganize in response to situational and developmental stress. This is evident in the answers of the participants who expressed the view that through the rehabilitation programme they gained the knowledge and a better understanding of the adolescent. As a result, the participants reported that they were able to claim back their authority and become more involved in scheduling their adolescent's free time. However, the parents' actions of claiming back authority seemed to affect the sibling subsystem, because other family members ended up enduring the consequences of the adolescent abusing substances.

"I've learnt ek kan dit nie meer bend nie. I need to stick to it. Die selfde met (youngest son), dit vir my kom leer om meer disciplined te wees. If I say, "no TV" dan gaan ons no TV het, of dit nou vir my ook curb, it is fine, you know... "

[I've learnt that I can't bend it anymore. I need to stick to it. The same with (youngest son), I learnt to be more disciplined. If I say: "No TV", then we will have no TV, even if I also have to be curbed. It's fine, you know.] (Participant 4)

Previous studies have also indicated that parents' roles in the family environment include preparing children for adulthood through rules and discipline (Hoskins, 2014). The above comment was in line with the key informant's explanation that the participants were assisted with skills training regarding parenting roles and new parenting skills. These skills led the participants to modify their parenting styles in order to enhance their relationships with the adolescents. Participants were now able to identify that different methods of parenting that could be used with different age groups and different situations.

"So it's also, once again setting aside the old and learning the new skills and developing the parent and then of course the child... Bring in the different styles with different children, different age groups, and different personalities." (Key Informant)

New way of communicating

Parent-child communication is a process whereby 'adolescents communicate with their parents about different topics, such as drugs and alcohol, sex and/or birth control as well as personal problems' (Hoskins, 2014: 513). Participants perceived that the new way of communication appeared as an enabler for an open and understanding relationship with their adolescents, thus improving parent-child communication.

"Nou is en toe moet ek nou buy into it, en ek moes nou met almal praat want ek moes nou mos dinge different doen en toe se ek ma nou okay (person's name) kan ma nou hier bly."

[And so I had to buy into it and I had to speak to everyone. I had to do things differently and I said: Okay now (person's name) can now also stay here "]. (Participant 4)

Hoskins' (2014) review of parenting consequences on adolescent outcomes revealed that a good relationship with mothers enables adolescents to share about problem behaviour. In the current study participant 2 shared that "Sometimes I feel that he is really telling me the truth that he's not smoking". One participant reported that there were set boundaries in place in order to prevent risky behaviour. The boundaries were considered as enablers to monitor the adolescents' behaviour.

"Well, they know there are boundaries, there are times set out, and that they got to be at home." (Participant 2)

"Moving together as a family"

Parental warmth and support create a supportive environment where adolescents would be able to discuss any concerns and their problems with their parents without fear (Hoskins, 2014). The heading for this section comes from an interview with participant 2 who explained the importance of the parent-child relationship. The rationale behind the parent-child relationship to work towards goal setting and the future of the family. Participants indicated that as a family they were now more motivated to educate/enable the community about drug awareness and to provide support to parents in the community facing similar situations.

"My goal for him is that, he can become a successful athlete and he got some other plans also and getting an entrepreneurship doing his welding and his music. Yeah, definitely, we going to try and open a support group this side for parents that is in the closet and come out and get, get the community involved with your child . so . we don't going to give up and he's also going to work with kids just to tell them what it is being without a mother in a different environment and what you have done to your mother, your father, your family basically." (Participant 2)

The findings above support Hoskins' (2014) explanation of community capacity building which allows people to share responsibility for the common welfare of the community and individuals. This indicates that the parents realised that there was a need to address community needs and confront situations that seemed to be problematic in the community such as substance abuse.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH PROMOTION IN PARENTING ADOLESCENTS

The findings in this study have three implications related to health promotion in parenting adolescents abusing substances: developing parental skills, strengthening community action and creating a supportive environment.

With respect to developing parental skills, the study offers some insight into how parents living with adolescents abusing substances may be assisted with more training on family adaptability, parenting styles and adolescent handling skills. It is believed that the parenting skills would enable the parents to cope with the experiences of parenting adolescents abusing substances. In addition, the parent-child communication channels would be enhanced so that they could have a platform to share ideas and decisions.

Strengthening community action emerged as one key finding in "moving together as a family". Taken together, these findings suggest a role for communities and families in promoting the wellbeing of parents and adolescents in their social and working environments. This action will enable the formulation of partnerships to create a supportive environment for parents, families, friends and substance-abusing adolescents with the involvement of faith-based organisations, rehabilitation centres and other stakeholders such as social workers and occupational therapists.

CONCLUSION

The study provided an insight into parents' experiences of parenting adolescents abusing substances. Overall, the findings of the current study indicated that authoritarian, authoritative and permissive parenting styles emerged as strategies that parents had to use in order to manage the situation in their families. Additionally, the findings of this study reveal that adolescent substance abuse has severe consequences for the parent-child subsystem, because it influence parental communication and the family's wellbeing. The present study confirms previous findings and contributes additional evidence that suggests parenting skills and competencies should be enhanced to enable parents to cope with the challenges of dealing with adolescent who are abusing substances. It has been shown from the findings that the parents who attended the training at rehabilitation centre were enabled with effective skills such communication, coping strategies and parenting styles. One of the more significant findings to emerge from this study is the importance of parents' religion that enriched their faith which kept them strong to persevere while parenting an adolescent abusing substances. The findings also highlighted the importance of the community resources such as religious institutions and support groups which assisted the parents to deal with the stressful events in their lives. The community capacity building that we have identified therefore assists in our understanding of the role of parents in communities and faith-based organisations in formulating collaborative partnerships in parenting projects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the following students for their work on their mini-theses in partial fulfilment of their BSc Occupational Therapy degree.

1. Ms Shineil Bains, Fourth year Occupational Therapy student, student number: 3064616, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

2. Ms Lauren Weavers, Fourth year Occupational Therapy student, student number: 3064535, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

3. Ms Courtney Peters, Fourth year Occupational Therapy student, student number: 3064640, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

4. Ms Naidene Brown, Fourth year Occupational Therapy student, student number: 3066244 Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

REFERENCES

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY. 2013. Facts for families: Teens- alcohol and other drugs. [Online] Available: http://www. aacap.org/App_Themes/ AACAP/docs/facts for families/03 teens alcohol and other drugs.pdf. [Accessed: 22/07/2014]. [ Links ]

BANDURA, A. 2011. Social cognitive theory. Handbook of social psychological theories. 349-373. [ Links ]

BARNES, H. L. & OLSON, D.H. 1985. Parent-Adolescent communication and the Circumplex model. Society for Research in Child Development, 56: 438-447. [ Links ]

BAUMRIND, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Development Psychology, 4(1: 1-103. [ Links ]

BORNSTEIN, M.H. 2001. Parenting: Science and Practice, Jan-June 2001 1 (1&2): 1-4. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

BRAUN, V. & CLARKE, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2): 77-101. [ Links ]

COE, N. 2009. Exploring attitudes of the general public to stress, depression and help seeking. Journal of Public Mental Health, 8(1): 21-31. [ Links ]

COOK, A. SPINAZZOLA, J. FORD, J. LANKTREE, C. BLAUSTEIN, M. CLOITRE, M. DEROSA, R. HUBBARD, R. KAGAN, R. LIAUTAUD, J. MALLAH, K. OLAFSON, E. & VAN DER KOLK, B. 2005. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5): 390-398. [ Links ]

DADA, S. & HARKER BURNHAMS, N. 2017. South African Community Epidemiology Network of Drug Use (SACENDU): Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug abuse treatment admissions in South Africa. [Online] Available: www.mrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/attachments/2017-05-22/SACENDUPhase40.pdf. [Accessed: 17/03/2017]. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2017. NATIONAL DRUG MASTER PLAN 20132017. [Online] Available: http://www.dsd.gov.za/index2.php?option=com_docman&task=-docview&gid=414&Itemid=3. [Accessed: 17/03/2018]. [ Links ]

DOLORES, M.A. & TONGCO, C. 2007. Purposive sampling as a Tool for Informant selection. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 5: 147-158. [ Links ]

GROENEWALD, C. & BHANA, A. 2016. Substance abuse and the family: An examination of the South African policy context. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(2): 148-155. [ Links ]

HOSKINS, D.H. 2014. Consequences of parenting on adolescent outcomes. Societies, 4: 506 - 531. [ Links ]

KREFTING, L. 1991. Rigor in qualitative Research: Establishing trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3): 214-222. [ Links ]

KÜHN, J. & SLABBERT, L. 2017. The effects of father's alcohol misuse on the wellbeing of his family: Views of social workers. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 53(3): 409 - 422. [ Links ]

LEWIS-BECK, M. S., BRYMAN, A. & FUTTING LIAO, T. 2004. [Online] Available: http://dx.dio.org/10.4135/9781412950589 [Accessed 27/03/2014]. [ Links ]

MABE, P. A., DELL, M. L. & JOSEPHSON, A. M. 2011. Spiritual and religious perspectives on child and adolescent psychopathology. Religious and spiritual issues in psychiatric diagnosis: A research agenda for DSM-V, 123-142. [ Links ]

McKEGANEY, N., BARNARD, M.B. & MCINTOSH, J. 2002. Paying the price their parents addition: meaning the needs of children of drug using parents. Drug: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 9(3):233-246. [ Links ]

MENAGHAM, E.G, & PARCEL, T.L. 1995. Social Sources of Change in Children's Home Environments: The Effects of Parental Occupational Experiences and Family conditions. Journal of Marriage and Family Conditions. 57(1) 69-84. [Online] Available: URL: http://www.jstor.org./stable/353817. [Accessed: 14/03/2018]. [ Links ]

MORETTI, M. M. & PELED, M. 2004. Adolescent-Parent Attachment: Bonds that support Healthy Development. Paediatric Child Health, 9(8): 551-555. [ Links ]

OBURU, P.O., PALMERUS, K. 2003. Parenting Stress and self-reported discipline strategies of Kenyan care-giving grandmothers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6): 505512. [ Links ]

OLSON, D.H. 2000. Circumplex model of Marital and Family Systems. The Association for Family Therapy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 22: 144-167. [ Links ]

SARKADI, A., KRISTIANSSON, R., OBERKLAID, F. & BREMBERG, S. 2007. Fathers' Involvement and Children's Developmental Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Acta Paediatrica. 97: 153-158. [ Links ]

SUTTON, J., & AUSTIN, Z. 2015. Qualitative research: Data Collection, Analysis and Management. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 68(3): 226-231. [ Links ]

TIMMONS, SM. 2012. A Christian faith-based recovery theory: understanding God as sponsor. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(4): 1152 - 1164. [ Links ]

TSHITANGANO, TG. & TOSIN, OH. 2016. Substance use amongst secondary school students in a rural setting in South Africa: Prevalence and possible contributing factors. African Journal of Primary Health Care Family Medicine. 8(2): a934. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v8i2.934 [ Links ]

VAN WYK, B. 2012. Research design and methods: Part 1. [Online] Available: http://www.uwc.ac.za/Students/Postgraduate/Documents/Research_and_Design_I.pdf. [Accessed: 17/03/2018]. [ Links ]

VISSER, M. & ROUTLEDGE, L. 2007. Substance abuse and psychological well-being of South African adolescents. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(3): 595 - 615. [ Links ]

WEGNER, L. & FLISHER, A. J. 2009. Leisure Boredom and Adolescent Risk Behaviour: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 21(1): 1-28. [ Links ]

WEGNER, L., AREND, T., BASSADIEN, R., BISMATH, Z. & CROS, L. 2014. Experiences of mothering drug-dependent youth: influences on occupational performance patterns. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44(2): 6 - 11. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2017. Social Determinants of Health. [Online] Available: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/. [Accessed: 19/03/2018]. [ Links ]