Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.54 n.2 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-629

ARTICLES

"Sharing of findings and recommendations remains a fallacy": reinvigoration of the dissemination and implementation of social work doctoral research findings

Mankwane Makofane

Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Research is the backbone of social work knowledge and practice. A qualitative study conducted to explore and describe the dissemination of research findings and implementation of practice recommendations among 31 doctoral graduates revealed that these processes seemed to be a mere afterthought. Sixteen graduates published articles from their theses, ten conducted workshops, another ten applied practice recommendations, while four published the findings and applied their recommendations. An indaba is suggested to develop a framework for the dissemination and use of recommendations through networks.

INTRODUCTION

As an integral part of social work, doctoral research advances new knowledge and makes a worthwhile contribution to practice and promotes the wellbeing of society.1 Its multifaceted role in social work education and practice requires innovation and creativity to respond to societal needs (Anthony & Austin, 2008:287). Social workers are reminded that practice is their purpose and that the profession's survival requires them not to lose their essential value for those they serve (Starr, 2007:2). Social work is

A practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing (International Federation of Social Work [IFSW] & International Association of Schools of Social Work [IASSW], 2014).

Thus, various epistemologies are employed to gain insights into phenomena, and develop knowledge and intervention strategies to improve the repertoire for practice. Interventions need to be responsive to the needs and empowerment of individuals, families, groups, communities and organisations. A PhD is not a Nobel Prize, as pointed out by Mullins and Kiley (2002). However, doctoral education prepares stewards of the discipline, who should generate new knowledge and defend it against criticism. Furthermore, stewards should conserve important ideas and findings,2 transform and conserve created knowledge by teaching different audiences (Golde, 2006:1; Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work [GADE], 2013). As stewards of the profession, doctoral graduates need to strive to perfect their craft and demonstrate expertise in their fields of study. Therefore, social workers do not pursue a doctorate for the sake of it.

A thesis is a culmination of a doctoral study used to report knowledge generated through empirical investigations for the advancement of the discipline, including personal and professional benefits. Research results should be disseminated to form part of the body of knowledge and enable researchers' entry into the discourse of the discipline; promote scholarly productivity; provide professional visibility for doctoral graduates (Dinham & Scott, 2001:45); improve career trajectories; serve as a foundation for future research, including postdoctoral work (Maynard, Vaughn, Sarteschi & Berglund, 2014:1047); be replicated or challenged by others (Yin, 2011:256); and benefit supervisors and institutions (Dinham, & Scott, 2001:45). Thus, documenting the valuable contributions made by social work doctoral graduates, and how their achievements have influenced the wellbeing of society, is crucial (Anastas, 2012:21).

When conducting research at doctoral level, candidates employ the research-based practitioner model, following a linear process. This model regards researchers as producers of knowledge, while practitioners are considered users thereof. A detailed exposition on two communities (or cultures) of creators of research and those who might use it is provided by Gray, Sharland, Heinsch, and Schubert (2015). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of research implementation3 remains a concern, in particular because it is clear that social workers still require skills and capacity in research processes.

This study was inspired, first, by curiosity to determine if and how doctoral research findings are disseminated and implemented to enhance societal wellbeing. Second, the paucity of South African literature on these processes raises concern, even though scholars are of the view that "the study of research utilisation is still at its infancy" (Gray et al., 2015:1953). Third, a comment in a thesis by Louw (2007:439) under a sub-heading on 'dissemination of research results' states that:

Because the research has been conducted in an academic environment and not practice, a dilemma exists on how to disseminate the results. On the one hand, the academic environment lends credibility to the results, but on the other there is no direct access to its use.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

In a rapidly changing economic, social, cultural and political landscape in SA, social work research has a potential to contribute responsively to societal needs. Although there is evidence describing effective interventions, there has been no substantive work on the dissemination4 of research findings (Bellamy, Bledsoe & Traube, 2006:23). Moreover, little is known about the distribution of information from doctoral theses (Maynard et al., 2014:1048) and the use of practice recommendations to promote best practice.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY

During preliminary investigations several doctoral research proposal guidelines from different schools/departments of social work were scrutinised. Generally, candidates are expected to explain the significance or potential value of the enquiry. Additionally, a few departments also require them to describe how their findings would be disseminated beyond completion of the thesis. Although it is not mandatory for graduates to publish their research results, they are expected to do so, given that publishing is an important part of the doctoral process (Dinham & Scott, 2001:46). Moreover, anecdotal evidence shows that during the recruitment process of potential participants, researchers are inclined to suggest that the findings will influence welfare policies in their favour.

The period from 2004 to 2014 was chosen for this study, since it was almost ten years after the advent of democracy in 1994. The new political dispensation led to the transformation of the welfare sector and the adoption of the developmental approach by the DSD that seeks to promote social development, social justice, and the social functioning of all people through an integrated approach Ministry for Social Development (White Paper for Social Welfare, 1997:15).

This paper, therefore, seeks to respond to the lacuna by making recommendations based on the outcomes of a qualitative study. It is anticipated that this presentation will ignite discourse among doctoral graduates in and outside academia and, furthermore, stimulate a desire among aspirant doctoral candidates, policymakers in the Department of Social Development (2013) (DSD), and welfare organisations to commit to the implementation of practice recommendations emanating from doctoral studies.

RESEARCH QUESTION AND GOAL

The overarching research question that assisted in the navigation of the research process (David & Sutton, 2011:12) was: What are the methods used to disseminate and implement recommendations from social work doctoral research findings? The primary goal was to gain insight into the methods used by doctoral graduates in the dissemination and application of recommendations from social work doctoral research.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative exploratory descriptive inquiry was undertaken among doctoral graduates who qualified between 2004 and 2014. Research reports were accessed through the electronic theses and dissertations' (ETDs) platform from various universities in South Africa. The theses were perused to determine the type of study conducted and practice recommendations made.

Purposive and snowball sampling techniques were applied to identify doctoral graduates who completed their degrees during the stipulated period. Positive feedback was received from a doctoral graduate who took part in the pilot testing of open-ended questions contained in the data-collection instrument, and no amendments were made. The data gathered from pilot testing does not form part of this presentation. An invitation letter, ethical approval granted by the Research Permission Subcommittee (RPSC) (Ref # 2016_RPSC_075) at Unisa and guiding open-ended questions in English were emailed to doctoral graduates. These graduates' names and e-mail addresses were obtained online or from supervisors and colleagues.

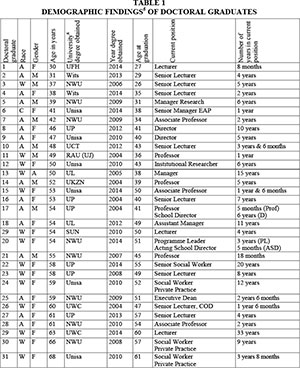

Online communication afforded graduates an opportunity to write their own responses. According to Willis (2011:142), "[t]he social interaction between online personas produces equally fruitful data for social researchers as off-line communication methods." E-mails made it possible to reach potential doctoral graduates across the country, while the reiterative process facilitated communication with graduates when seeking clarification of their responses. Thirty-one graduates completed and signed a consent form to confirm their voluntary participation in the inquiry. From the 31 doctoral graduates (Table 1), 28 e-mailed their responses to the researcher and 3 opted for telephonic interviews, conducted by an assistant researcher with a doctorate, which were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Data were thematically analysed by the author and an independent coder, guided by the eight steps posited by Tesch (Creswell, 2009). Cross-checking the coding facilitated sound analysis and authentication, and increased the credibility of the study. The demographic data on the graduates are presented in Table 1 below.

Social work is a female-dominated profession. Hence, 21 female graduates (10 Africans, 1 Coloured and 11 Whites) and 9 males (7 Africans and 2 Whites) took part in the study.

The mean age of the graduates at the time of the study (2017) was 51.29 years, while their mean age at completion of their studies was 44 years. Of the 31 graduates, 11 women obtained their degrees when they were between ages 50 and 61. This trend is attributed to the multiple roles that women play at different stages of their lives. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to note that young social workers are also pursuing doctoral studies. Six graduates (3 in public service, 2 in the private sector, and 1 in academia) indicated that their degrees did not contribute to their appointment to their current positions, which they had occupied prior to studying for a doctorate.

The following discussion is based on the graduate-supervisor relationship after graduation.

Descriptions of the graduate-supervisor relationship after graduation

Compelling evidence suggests that doctoral graduates are more likely to publish if they receive assistance, information encouragement from supervisors and other academic mentors, including clear information on institutional policies on postgraduate publication (Dinham & Scott, 2001:49). Some responses attest to the positive effects of supervisor support of the graduates' achievements.

My promoter has remained a mentor and also served as a guide when planning what to do with the recommendations. I also received guidance and support regarding the writing of journal articles.

He created opportunities for me to present my findings to local and international conferences.

These encouraging experiences are consistent with the role of a protagonist and motivator (viewed as "planting a seed") assumed by supervisors after submission of theses for examination (Timmons & Park, 2008:746). Conversely, a strained relationship seemingly characterised by power differentials was reported as follows:

My promoter and I had conflictual political positions. However, my promoter had the most excellent research competencies that I lacked as a practitioner/activist. The relationship died a natural death soon after graduation.

We held drastically opposing views on every aspect of... and the political, social and psycho-social aspects/contexts.

Unfortunately, the non-existence of a supervisor-graduate relationship after graduation denotes the cessation of possible publication of research findings and/or future research collaborations. In order to salvage graduates' unique contributions, it would be worthwhile for mentors to encourage and persuade graduates to disseminate and implement their research findings. Alternatively, intervention by a third party may be sought.

Aspects raised by graduates on the distribution of research findings are presented below.

-

Publication of research findings

Ideally, the planning process for dissemination of the research findings should occur at the beginning of the project; unfortunately, this was found not to be the case in the current study. Nevertheless, it is believed that the best research is often published soon after completion of the thesis or degree (Vijayakumar & Vijayakumar, 2007:69). Doctoral graduates are accountable to publish their research results with encouragement and support from supervisors. Accountability is central to social work, even though it is regarded as complex and multifaceted in social work research (Dominelli & Holloway, 2008:1017). Graduates are expected to articulate and demonstrate the value of their studies to those affected as well as to the public. Failure to disseminate research findings is a contravention of one of the cardinal principles of qualitative research, namely giving participants a voice (Jack, 2010).

The task of publishing without assistance may be daunting for graduates (Dinham & Scott, 2001:46). In most cases candidates view the publishing process as complex and difficult to navigate. They do not know how to revise, select and reduce the thesis to conform to the conventions of a specific journal (Lyytinen, Baskerville, Iivari & Te'eni, 2007:317; Bender & Windsor, 2010:149; Jalongo & Saracho, 2016:133). Hence, supervisors as mentors (after graduation) and co-authors need to determine the suitability of the doctoral work for publication, which may be indicated in examination reports; they should also assess graduates' abilities and motivation to produce an article; identify suitable journals (guarding against predatory publishers); determine the impact factor of different journals; and take an active part in the writing of the journal article to ensure that it meets the required standards. Co-authorship is important in preparing graduates for post-doctoral work (Kamler, 2008:286).

However, anecdotal information shows that some supervisors take over the process of turning the thesis into a publication(s), while the candidate is expected to provide accurate references (Timmons & Park, 2008:746). Such practices defeat the purpose of affording graduates an opportunity to hone their writing skills and confidence. Benjamin Franklin said: "Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn."

A concern raised by a graduate who is a manager of research for a provincial government department is disconcerting. He stated that:

In most instances you would even find that a research project was undertaken with a specific programme/project of a government department, where at times social workers were the research participants, but sharing offindings and recommendations remains a fallacy. I have not, given my years of experience, seen any scholar/researcher engaging with the relevant department for the dissemination of their findings and recommendations except for those commissioned by government/departments.

This indictment raises a question as to the type of agreement doctoral researchers have with welfare organisations or government departments. This also serves as a wakeup call to all role players in the social work fraternity across South Africa.

-

Methods used for the dissemination of research findings

Graduates' actions and activities must always be underpinned by accountability, responsiveness and responsibility. The outcomes of the study shows that a wide range of service providers, students, social workers, and organisations benefited from publications by 17 graduates (Table 3). Modes of dissemination varied from a single to a combination of several methods such as publication in academic journals, presentations to target groups, communities, colleagues and students; and presentations at national, regional and/or international conferences. Furthermore, other modes of dissemination included submission of reports to the National Research Fund (NRF), offering training through workshops and continuing professional development (CPD) accredited by the South African Council for Social Service Professions, 2017 (SACSSP).

The abovementioned undertakings underscore the fact that new knowledge from research should be taught to different audiences in and outside of formal classrooms (Golde, 2006:1). Failure to meet this obligation will deprive social workers of knowledge and skills required to offer effective services to those in need. Unpublished research results suggest a failure of doctoral education (Maynard et al., 2014:1046). Overall, the number of journal articles co-authored by graduates and supervisors varied from one to four.

It is not surprising that graduates in academia are the most published, since universities reward and promote academics "based largely on publication rather than public accomplishment" (Basken, 2016:4). Furthermore, Basken (2016:4) documented personal experiences of scholars (from various disciplines) aggrieved and demotivated by a reward system that places emphasis on publishing rather than public service. The "publish or perish" mantra is also viewed by others in academia as placing pressure on academics to an extent that some may design research that could be completed and published within the shortest period of time, and thus fail to develop practice-based research to address the needs of service users.

The literature indicates that dissemination of information alone is insufficient (Gira, Kessler & Poertner, 2004:77), meaning that a single method of dissemination of research findings will not ensure publication of results to all target groups. This sentiment resonates with the following comment:

It should be borne in mind that these forums (journals, conferences etc.) alone cannot convey the message across adequately. This is simply because not all practitioners will attend and have access to these platforms.

Besides practitioners' access to information, methods of dissemination of findings have a bearing on individuals' receptiveness. Provision of information "may not lead to changes in the practice of social workers" (Gira et al., 2004:69). Hence, passive dissemination of research results does not equal their use in practice (Humphris, Littlejohns, Victor, O'Halloran & Peacock, 2000:517). The challenge is compounded by the fact that research results for the most part do not benefit those who are in a position to implement them in practice. Instead, they are often read by researchers with access to peer-reviewed journals and academic conferences (Halvorsen, 2017:129).

-

Application of practice recommendations

The use of research findings has long been recognised as an important factor that influences the success and development of best practice. Useful interventions will have minimal impact if they remain hidden away in professional journals (Fritz, 2016:8). While there is agreement that practice is fundamental in social work, there are few studies on the implementation of research findings. Evidence from the current study suggests that graduates who succeeded in implementing practice recommendations had pursued practice-based studies. Graduates in private practice have leeway to implement practice recommendations without concern for organisational issues. However, since the use of research findings has not been assessed or evaluated, there is no evidence as to "what actually works (or how much it works), for whom and in what contexts" (Stevens, Liabo, Witherspoon & Roberts, 2009:16).

Among the graduates who developed practice guidelines and intervention programmes, only one reported on piloting "[a] life coaching programme for the support of social work students within an open and distance-learning context" and assessing its level of success and challenges.

I obtained funds in 2014, developed and piloted the online programme [in two universities] in an effort to "sell" the developed programme to colleagues in order to include it in the new curriculum.

Piloting provides evidence on the feasibility of a programme, enabling the researcher to identify potential risks and modify areas of concern before implementing it on a larger scale. Outcomes of a pilot project will help allay the fears of sceptics and inspire confidence in the initiator.

Seventeen doctoral graduates who are in academia did not implement practice recommendations, stating that it was not their responsibility.

Not much was done for implementation of recommendations in relation to practice; firstly, I am not practising social work. I am in academia.

This notion is contrary to the directive of the South African Council on Higher Education (CHE), which is an independent statutory body in higher education. It recognises community engagement as one of the three core responsibilities of higher education. According to CHE (2010:3), "[u]niversities are called upon to demonstrate social responsibility ... and their commitment to the common good by making available expertise and infrastructure for community service programmes". Therefore, community engagement is one of the key performance areas for academics that provide opportunities to conduct innovative research for the upliftment and development of communities. Thus, community engagement should be used by graduates in academia as a vehicle to disseminate and implement their research findings.

-

Support from supervisors during implementation of practice recommendations

Three graduates received casual support from their supervisors during the implementation process.

She asked about my progress and motivated me to continue implementation efforts.

She availed herself in cases where she was needed.

Regardless of the linear process adopted by candidates (when conducting research as creators of knowledge), ideally, the implementation of practice recommendations should be initiated by the novice researcher (doctoral graduate) with support from the supervisor. However, in my opinion, graduates may also use social media to advertise and engage colleagues on interventions they have developed, and pledge support to those who attempt to put them into practice. Accessibility to assistance and support will provide researchers (graduates) with the confidence to apply their interventions. After that the assessment and evaluation of the implementation process should be encouraged and outcomes published to share experiences with colleagues on the successes, challenges and implications for practice.

-

Graduates' perceptions of their success stories

Two graduates developed training in the field of substance abuse. One offered training to bouncers employed in liquor outlets such as taverns and shebeens,7 while another offered training to social workers through the CPD workshops.

Some bouncers serving different alcohol outlets were trained on how to address violence, and are implementing the provided strategies/skills [study was on binge drinking and interpersonal violence].

Protection of patrons against intimidation and violence by knowledgeable and skilled bouncers is important. Hence, the owners of these establishments have employed bouncers to maintain order. There is a plethora of literature on the relationship between alcohol and violence (Graham & Livingston, 2011). Another study "investigated the effect of outlet numbers and alcohol sales on the risk of assault in Western Australia" (Liang & Chikritzhs, 2011).

The second graduate stated:

My success is viewed as the CPD workshops (over a period of 4 years) resulting in practitioners developing plans and implementing the plans based on the recommendations of the study. I make contact with attendees 4 months after the workshops and feel positive about the impact of this form of dissemination. - P3 (Developed 3 CPD short courses) [study was on aftercare for chemically addicted adolescents].

From 1 April 2010 it became mandatory for social workers to participate in CPD training to keep abreast of new developments in their fields of practice and promote excellence in practice (SACSSP Guidelines for CPD, 2017). As change agents, social workers need to be empowered through continuous and sustainable capacity-building training. Hence, contributions by graduates towards capacity building of practitioners are commendable and encouraged.

Another graduate who focused on developing a policy framework on risky behaviour among commercial sex workers stated the following contribution from her study:

Most of the approaches in the study assisted social workers to do their work better and with the understanding of [the relationship between] substance abuse and sex work [study was on intervention research among commercial sex workers].

Risky sexual behaviour is detrimental to the health of involved parties who may be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STIs) and/or human immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV). It is therefore imperative for social workers to be au fait with relevant and appropriate approaches and to apply them in practice.

The formation of support groups by graduates demonstrates their passion to bring about positive changes in people's lives. Group members benefit maximally from interactions with others who share similar challenges. Emotional support enhances a sense of belonging and instils hope in members to overcome challenges.

The establishment of a support group [of teenagers on issues related to suicide] was a success - 100% support from the school as a whole, i.e. school head, relevant educators, learners; setting and access were all good [study was on suicide among Black teenagers].

Support from role players facilitated the realisation of set goals and helped to turn an initiative into a reality. Likewise, another graduate reported a successful support group intervention that is still continuing.

I initiated a support group at my workplace for mental health care users and their families, which is now run by social workers and occupational therapists. I am implementing instruments that I developed during my research [study on mental health].

Support groups are critical in mental health settings to promote members' wellbeing through cohesion and mutual aid. Group work and ubuntu are entrenched in the spirit of interconnectedness that says "I am because you are", which includes emotional and practical concern for the wellbeing of others (Metz & Gaie, 2010:284).

One of the graduates developed a multicultural scale that measures the social health of military employees and families, and is still currently in use.

My research has always been applied and has aimed to strengthen the quality and range of services social workers can provide to clients. So, the widespread and sustained use of the tool over about 15 years, and with several thousand soldiers every year, is something I feel very proud of and happy about. My thesis just lies on a shelf, but the tool is alive [study was on multicultural scale development in social work].

This archetypal contribution illustrates the advancement of practice through research. Hopefully, the graduate's accomplishment will ignite enthusiasm and a desire to continue pursuing worthwhile research. It will also serve as an encouragement for others.

-

Challenges experienced by graduates during the implementation of practice recommendations

Different factors may hamper and jeopardise the implementation processes to varying degrees. The literature highlights the barriers to the implementation of research results as workload pressures, time limitations, insufficient staff resources, workload constraints, lack of organisational support for implementing research results, and lack of authority to change practices (Humphris et al., 2000:517; Mullen, Bledsoe, & Bellamy, 2008:332).

One of the barriers that hindered graduates from implementing practice recommendations is change of jobs.

No implementation. I left SAPS [South African Police Services] after the research.

I did not embark on the process [implementation] as I joined academia shortly after PhD.

I have not implemented the recommendations in practice based on the fact that I am not working actively in the field.

The transition from one employment position to another should not be perceived as an impediment, but as a golden opportunity to further one's research interests and optimise collaboration with colleagues remaining in the organisation.

The career trajectories for doctoral graduates are often linked to academic careers or aspirations, which leads to a general misconception that all graduates should join academia. Hence Lyons (2002:345) cautions against "excessive academisation", which creates a gap between social work academy and professional practice. Doctoral graduates who remain in government, non-government organisations (NGOs) and the private sector are strategically placed to influence the development and application of effective intervention programmes including policies and should be lauded.

An appeal is made to educators not to shy away from practice, as this may lead to apathy or scepticism towards practice (Chan & Ng, 2004:312). Furthermore, the authors challenged educators "to adopt a holistic practitioner-researcher-educator role in their everyday role in order to create the necessary impact to effect change" (Chan & Ng, 2004:312). Daunting as the opinion may sound, it needs serious consideration.

Fear of change and resistance from colleagues and managers posed a challenge to/for another graduate.

Challenges were few. It is important to mention that some of the Senior Managers in the Department [government] were not supportive, but the researcher [I] had to seek approval from the Director-General in the Department and then the challenge was overcome.

Withdrawing from situations due to reluctance by colleagues to embrace a new intervention strategy should not be an option. Irrespective of misgivings from some colleagues, social workers should steadfastly champion the course of social change through the development of needed resources and the promotion of social justice for vulnerable and indigent service users.

Colleagues' resistance to change had an adverse effect on this graduate's morale.

I encountered a lot of negativity while developing the programme within the department [academia]. After an illness in 2015, I lacked the strength to push forward in efforts to implement the programme. It is only now that I am starting to develop momentum again. It feels as if I have to resell the same programme to staff over and over again, often only receiving criticism.

Reluctance of educators to support a new initiative may be devastating to the initiator. For a long time people's resistance to change has been identified as a barrier in organisations. However, it is purported that "people do not resist change per se, rather resist the uncertainties and the potential outcomes that change can cause" (Waddell & Sohal, 1998:547). Therefore, sharing the outcomes of a pilot study with colleagues may help allay their fears or concerns.

Organisational or systemic barriers were also cited as the reluctance of some NGOs and government welfare agencies to implement research-based practice recommendations.

Challenging, because welfare organisations, especially NGOs are doing crisis management and do not have the time to implement new recommendations.

Quite challenging. You'd expect that since it's evidence-based, organisations and government would want to use the information [research on child trafficking], but this was not the case.

The focus on crisis intervention by the NGO sector is generally attributed to lack of staff because of shortage of funds. NGOs and government agencies are experiencing high, unmanageable caseloads. Such a situation does not inspire social workers to embrace new interventions with enthusiasm, let alone implement them in practice.

Another response encapsulates the frustration experienced by a doctoral graduate as a result of change in organisational management.

The discussions (on a high level in terms of planning) have not yet resulted in active implementation. For me, it has been a frustrating experience. My experience has been that discussions result in a lot of ideas, me developing a plan based on these discussions, and then no follow-up. Another frustration is that people change positions and that the previously done work is not being conveyed to the new person in the position. Then, I have to start the discussions from the beginning.

Lack of seriousness and commitment to the advancement of progress and development by those in authority is a stumbling block that thwarts development and transformation. Interaction with organisational structures on envisaged research ventures should be pursued as opposed to relying on discussions with individuals in authority. Informal agreements between researchers and managers of welfare organisations can lead to parties reneging on verbal agreements and commitments.

A plethora of information suggests that scientific knowledge is often underutilised by social workers (Mullen et al., 2008:325). This, to a large extent, leads to the perception that social workers' lack of research knowledge is one of the reasons why the profession is held in such low regard.

Mostly SWs [social workers] are lacking knowledge regarding research methods. This leads to social work not having the same status as a profession like psychology.

Cultivation of a research culture among practitioners is long overdue. The time is right to launch investigations on how professionals should be "energized to recognize the internal and external value of undertaking quality research, the necessity of having solid research to advance the profession's knowledge base" and the importance of a research-focused profession to strengthen social work's position among other behavioural and health professions (Zlotnik, Biegel & Solt, 2002:320).

Inaccessibility of policy makers is in stark contrast to the DSD's goal of encouraging and promoting participation, democracy and collaborative partnerships among all social service role players and stakeholders (DSD, 2013).

Very difficult to access policy makers if not during conferences and they have a different agenda, which is political, not focusing on what one brings as empirical evidence findings.

Inaccessibility of policy makers may be compounded by political agendas that are not necessarily reality based and may thus threaten desired progress, development and provision of quality service. Ironically, this conduct violates the Batho Pele (people first) principles of consultation, openness and transparency that seek to promote a better life for all South Africans by putting people first (Department of Public Service and Administration, 2015).

Time constraints was mentioned by graduates in academia as a reason for their failure to implement practice recommendations. This raises a pertinent issue on the lack of information on how educators use time allotted to them by universities to fulfil their community engagement responsibilities.

Time, time, time...

Honestly, this was never done - it was outside my scope of practice.

First and foremost when in academia it is very difficult to disseminate the findings and recommendations of our studies to the practitioners on the ground. I am not sure if it is difficult or we simply do not do it.

Surprisingly, none of the educators made reference to time allocated by universities for community engagement. Educators require effective time-management skills to meet their mandate. For instance, at Unisa educators are allocated a minimum and maximum percentile of their time for community engagement activities.

-

Mentoring by supervisors after graduation

Most graduates proposed that supervisors should become mentors after graduation. Ironically, most of the graduates had indicated earlier in their responses that there was no need for supervisors to play any role during the implementation of practice recommendations, citing the reason that the supervisor's "job ofproducing a PhD was done."

Some of their responses are as follows:

Quite frankly, they must create/facilitate the dissemination of findings in conferences and publications.

Mentoring for at least 6 months' post-graduation and a realist discussion (prior to graduating) on how doctoral candidates can implement their findings and recommendations. However, I do understand that their role ends when the candidate graduates, as they are not remunerated or given any incentives for any extra work done thereafter.

Mentors to present papers at conferences. Mentors to draft manuscripts for publication. Guidance to apply for academic job interview. Preparation for academic job interview. Mentor during first 24 months in academia.

Aside from the proposed timeframes for mentorship alluded to above, essentially these excerpts express graduates' need and desire for support and guidance when venturing into the unfamiliar territory of publishing research findings. Some doctoral candidates may have misconceptions on the publication process and editors' expectations (Bender & Windsor, 2010:148). Due to the demands of pursuing their own scholarly research and supervising enrolled doctoral candidates, supervisors may not have time to mentor doctoral graduates (Grant & Tomal, 2015:183). However, the dividends of investing in doctoral graduates are substantial and likely to benefit graduates, supervisors, institutions and the profession alike. As a result, graduation should be seen as signifying the end of doctoral studies and the beginning of a lifelong commitment to making a contribution to the discipline through research and other rigorous practical endeavours.

-

Proposal for reinvigorating the dissemination and implementation of doctoral research findings

Although pockets of good practice and excellence exist, strengthening the dissemination and implementation of doctoral research findings requires radical transformation to address the challenges. It is unreasonable to expect doctoral graduates to produce articles shortly after graduation, when they have not been informed of, and prepared for, the purpose, process, product and benefits of doing so. The following excerpt demonstrates the lack of guidance for the candidate.

A draft article was a requirement for graduation to share the research results. At that stage, I had no clue why we were submitting this draft as a result I do not know what happened to it as it was submitted to the examination department.

Similarly, the literature shows that doctoral candidates do not receive adequate mentoring or structural support to publish from their research (Kamler, 2008:283).

Since doctoral candidates are in "the business" of knowledge production and development of relevant and responsive intervention strategies, they should not function in a vacuum or in isolation, but should be encouraged to think holistically from the beginning of the programme. Dissemination and implementation of research results are fundamental to knowledge advancement, participation in global discourse and improvement of practice. It is imperative that candidates realise in advance that graduation is the culmination of their studies, but a beginning of a new venture of "writing from and beyond a thesis" (Kamler, 2008:283). Therefore, the development of effective publication strategies is vital. Unless proper steps are taken to address identified shortcomings, South African social workers will continue to lag behind on evidence-based practice (EBP).

Effective dissemination and implementation of research findings requires collaboration between researchers and practitioners (Osterling & Austin, 2008:295). Thus, candidates should be encouraged to establish relationships with the public and with private organisations, including practitioners in private practice (offering services in their fields of interest) immediately after registration for the social work doctoral research proposal module (as at Unisa). These relationships should be nurtured and supported by supervisors to develop into iinethiwekhi zophando8 (research networks) for future facilitation of the dissemination and implementation of doctoral research findings following the strategies put forward by Mullen et al. (2008). Hopefully, these iinethiwekhi (networks) will expand into future collaborative research ventures at the provincial and national level.

Supervisors vary in their support of candidates writing for publication (Kamler, 2008:284). Instead of supervisors making arbitrary and unilateral decisions on supporting doctoral graduates to publish from their theses or not, I propose that members of the Department of Social Work, together with doctoral graduates from the public and private sector, should hold an indaba.9 The indaba is premised on the assumption that a diverse range of knowledge, experience and expertise will enhance the establishment of long-term relationships, and an exploration and development of a framework for the dissemination and implementation of research findings, as well as to processes to promote best practice. The consultative process will unleash the potential, creativity and innovation of different role players required to promote iinethiwekhi zophando. Role players will seize the opportunity to deliberate and influence doctoral education on pertinent issues related to decoloniality, indigenisation and Africanisation, and also offer lessons for culturally competent research (Kim, 2011:190).

An agreement should be concluded and signed to validate the commitment from those resolved and dedicated to supporting graduates in their endeavours to advance the profession for the benefit of humanity; a database could be created for this purpose. Such an agreement will assist candidates who did not conduct research under the auspices of a particular welfare organisation (especially those in academia) to be allowed space to implement their research findings after completion of their studies.

After registration of the thesis, module information sharing with candidates on, for instance, modes of dissemination and components of implementation should be gradual and systematic to avoid overwhelming them with information overload. What is important is to stimulate the candidates' "publishing productivity during doctoral education" (Green, Hutchison & Sra, cited in Kamler, 2008:284). Online discussion forums among supervisors and candidates should be utilised to engage in and clarify issues (Figure 1).

It is anticipated that the initiative will engender collaboration among supervisors in their quest to support graduates through the publication of their research findings. This is critical considering that "mentoring towards publication is not often a routine part of the process of doctoral education in the social sciences" (Kamler, 2008:283).

The collective development of a structured and concrete departmental framework will ensure that all candidates will be exposed to incremental learning of more or less the same content, which will dovetail with the thesis module. Since each candidate moves at a different pace, I am of the view that supervisors should take the responsibility to ensure that learning does take place. In this way, candidates will develop and continuously review and refine their strategies for the dissemination and implementation of their research findings. Cultivation of such processes will equip candidates with knowledge, and ignite their enthusiasm and desire to aspire towards publishing and implementing their research results. The support of supervisors (now mentors after graduation) provided to graduates during the application of practice recommendations will help allay their fears and boost their confidence.

This proposal is consistent with the tenets of the integrated approach adopted by the Department of Social Work at Unisa. It will eliminate the assumed schism that exists between researchers and practitioners, and open avenues for doctoral graduates to make their findings known and/or used under the auspices of welfare organisations.

It is therefore my opinion that the suggested progressive proposal will establish synergy between doctoral graduates and practitioners, and lead to constructive ways to undermine any myths around research. It will also advance the visibility of the contribution of social work doctoral research and its relevance to the advancement of the profession. Furthermore, practitioners will be assisted to transition through an ordinary service delivery model to a research-informed intervention model (Tischler, Webster, Wittmann & Wade, 2017:1). Such transformation will present opportunities for future collaborative research with invaluable benefits for service users, practitioners, doctoral graduates, supervisors, departments of social work, and universities.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To enhance the culture of scholarly research among educators and newly qualified graduates, the Department of Social Work should:

-

Enhance graduates' theoretical learning on the dissemination and implementation of their research findings through workshops (using various learning platforms, e.g. video conferences) four weeks after graduation;

-

Graduates should be exposed to different types of writing for diverse audiences through various guides on how to publish material from a thesis (Grant & Tomal, 2015). Retired professors may be considered for these responsibilities;

-

Invest in a writing coach to offer online coaching to supervisors, candidates and graduates. Ongoing coaching is a committed partnership that empowers participants to achieve beyond their current performance (Baldwin & Chandler, 2002:8);

-

Keep up the momentum, motivation and confidence building among graduates and supervisors by holding a colloquium, at least biannually, to report back to the larger community on research outputs; engage in professional dialogue on social work doctoral education and chart the appropriate way forward;

-

Embark on a rigorous recruitment drive for post-doctoral candidates.

CONCLUSION

The time has come for supervisors to assist doctoral candidates to develop and design comprehensive plans for the dissemination and implementation of their research findings. Unless significant steps are taken to address identified challenges, the implementation of evidence-based practice will remain a pipedream in South Africa. The suggested proposal is neither cast in stone, nor is it a panacea for all the challenges associated with the publication and application of doctoral research findings; it is, however, a first step in the right direction. The point is not to be right, but to get started. As Martin Luther King Jr said: "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter".

REFERENCES

ANASTAS, J.W. 2012. Doctoral education in social work: building social work research capacity. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

ANTHONY E.K. & AUSTIN, M. 2008. The role of an intermediary organization in promoting research in schools of social work: the case of the bay area social services consortium. Social Work Research, 32(4):287-293. [ Links ]

BALDWIN, C & CHANDLER, G.E. 2002. Improving faculty publication output: the role of a writing coach. Journal of Professional Nursing, 18(1):8-15. [ Links ]

BASKEN, P. 2016. Is university research missing what matters most? The Chronicle of Higher Education, 3-18. [ Links ]

BELLAMY, L.J., BLEDSOE, S. E. & TRAUBE, D.E. 2006. The current state of evidence-based practice in social work: a review of the literature and qualitative analysis of expert interviews. Journal on Evidence Based Social Work, 3(1):23-48. [ Links ]

BENDER, K. & WINDSOR, L.C. 2010. The four Ps of publishing: demystifying publishing in peer-reviewed journals for social work doctoral students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30:147158. [ Links ]

CHAN, L.W. & NG, S.M. 2004. The social work practitioner-researcher-educator. Encouraging innovations and empowerment in the 21st century. International Social Work, 47(3):312-320. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2009. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

DAVID, M. & SUTTON, C. 2011. Social research: an introduction (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SERVICE AND ADMINISTRATION. 2015. Batho-pele - people first principles. A better life for all South Africans by putting people first. Republic of South Africa Pretoria: Department of Public Service and Administration. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. Framework for social welfare services. Republic of South Africa. [Online] Available: www.dsd.gov.za [Accessed 20/03/2016]. [ Links ]

DINHAM, S. & SCOTT, C. 2001. The experience of disseminating the results of doctoral research. Journal of Further Education, 25:45-55. [ Links ]

DOMINELLI, L. & HOLLOWAY, M. 2008. Ethics and governance in social work research in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 38:1009-1024. [ Links ]

FRITZ, G.K. 2016. Editor's Commentary Dissemination of research findings: a critical step. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 32(12):8. [ Links ]

GIRA, E.C., KESSLER, M.L. & POERTNER, J. 2004. Influencing social workers to use research evidence in practice: Lessons from medicine and the allied health professions. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(2):68-79. [ Links ]

GOLDE, C. 2006. Preparing stewards of the discipline. [Online] Available: http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/perspectives/preparing-stewardsdiscipline [Accessed: 08/08/2016]. [ Links ]

GRAHAM, K. & LIVINGSTON, M. 2011. The relationship between alcohol and violence -population, contextual and individual research approaches. Drug Alcohol Review, 30(5):453-457. [ Links ]

GRANT, C.L. & TOMAL, D.R. 2015. Guiding social work doctoral graduates through scholarly publications and presentations. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 35:179-196. [ Links ]

GRAY, M., SHARLAND, E., HEINSCH, M. & SCHUBERT, L. 2015. Connecting research in action: perspectives on research implementation. British Journal of Social Work, 15:1952-1967. [ Links ]

GROUP FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF DOCTORAL EDUCATION IN SOCIAL WORK (GADE). 2013. Guidelines for quality in social work doctoral programs. [Online] Available: www.gadephd.org [Accessed: 08/08/2016]. [ Links ]

HALVORSEN, C.J. 2017. Bridging social innovation and social work: balancing science, values, and speed. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(2):129-130. [ Links ]

HUMRHRIS, D., LITTLEJOHNS, P., VICTOR, C., O'HALLORAN, P. & PEACOCK, J. 2000. Implementing evidence-based practice: factors that influence the use of research evidence by occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(11):516-522. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF SOCIAL WORK (IFSW) & INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF SOCIAL WORK (IASSW). 2014. Global definition of social work. [Online] Available: www.ifsw.org/policies/definition-of-social work [Accessed 22/06/2016]. [ Links ]

JACK, B. 2010. Giving them a voice: the value of qualitative research. Commentary. Nurse Researcher, 17(3):4-6. [ Links ]

JALONGO, M.R. & SARACHO, O.N. 2016. Writing for publication: transitions and tools that support scholars' success. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [ Links ]

KAMLER, B. 2008. Rethinking doctoral publication practices: writing from and beyond the thesis. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3):283-294. [ Links ]

KIM, Y. 2011. Pilot study in qualitative inquiry: identifying issues and learning lessons for culturally competent research. Qualitative Social Work, 10(2):190-206. [ Links ]

LIANG, W. & CHIKRITZHS, T. 2011. Revealing the link between licensed outlets and violence: counting venues versus measuring alcohol availability. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30:524-535. [ Links ]

LOUW, H. 2007. Men at the margins: day labourers at the informal hiring sites in Tshwane. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (D thesis) [ Links ]

LYONS, K. 2002. Researching social work: doctoral work in the UK. Social Work Education, 21:337-46. [ Links ]

LYYTINEN, K., BASKERVILLE, R., IIVARI, J. & TE'ENI, D. 2007. Opinion piece. Why the old world cannot publish? Overcoming challenges in publishing high-impact IS research. European Journal of Information Systems, 16:317-326. [ Links ]

MAYNARD B.R., VAUGHN, M.G., SARTESCHI, C.M. & BERGLUND, A.H. 2014. Social work dissertation research: contributing to scholarly discourse or the file drawer? British Journal of Social Work, 44:1045-1062. [ Links ]

METZ, T. & GAIE, B.R. 2010. The African ethic of ubuntu/botho: implications for research on morality. Journal of Moral Education, 39(3):273-290. [ Links ]

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION. 1997. Education White Paper 3. A programme for higher education transformation. Notice 1196. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

MINISTRY FOR SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 1997. White Paper for Social Welfare. Republic of South Africa. Government Gazette, Vol 368, No. 16943 (2 February). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

MULLEN, E J., BLEDSOE, S.E. & BELLAMY, J.L. 2008. Implementing evidence-based social work practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(4):325-338. [ Links ]

MULLINS, G. & KILEY, M. 2002. 'It's a PhD, not a Nobel Prize': how experienced examiners assess research theses. Studies in Higher Education, 27(4):369-386. [ Links ]

OSTERLING, K.L. & AUSTIN, M.J. 2008. The dissemination and utilization of research for promoting evidence-based practice. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 5(1/2):295-319. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL OF SOCIAL SERVICE PROFESSIONALS. 2017. Guidelines for continuing professional development [cpd] for social workers and social auxiliary workers. [Online] Available: http://www.sacssp.co.za/CPD/Guidelines [Accessed: 20/09/2017]. [ Links ]

STARR, R. 2007. Life, death, survival: Where goes our profession? [Message from the President.] Currents of the New York City Chapter, National Association of Social Workers, 52(2):2-12. [ Links ]

STEVENS, M., LIABO, K., WITHERSPOON, S. & ROBERTS, H. 2009. What do practitioners want from research, what do funders fund and what needs to be done to know more about what works in the new world of children's services? The Policy Press, 5(3):281-289. [ Links ]

TIMMONS, S. & PARK, J. 2008. A qualitative study of the factors influencing the submission for publication of research undertaken by students. Nurse Education Today, 28:744-750. [ Links ]

TISCHLER, S., WEBSTER, M., WITTMANN, D. & WADE, K. 2017. Developing and sustaining a practice-based research infrastructure in a hospital social work department: Why is it important? Social Work in Health Care, 56(1):1-12. [ Links ]

VIJAYAKUMAR, J.K. & VIJAYAKUMAR, M. 2007. Importance of doctoral theses and its access: a literature analysis. The Grey Journal (TGJ), 3(2):67-75. [ Links ]

WADDELL, D. & SOHAL, A.S.1998. Resistance: a constructive tool for change management. Management Decision, 36(8):543-548. [ Links ]

WILLIS, P. 2011. Talking sexuality online - technical, methodological and ethical considerations of online research with sexual minority youth. Qualitative Social Work, 11(2):141-155. [ Links ]

YIN, R. 2011 . Qualitative research from start to finish. London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

ZLOTNIK, J.L., BIEGEL, D. E. & SOLT, B.E. 2002. The institute for the advancement of social work research: strengthening social work research in practice and policy. Research on Social Work Practice, 12(2):318-337. [ Links ]

1 Adapted inaugural address by MDM Makofane presented at the University of South Africa (Unisa) on 16 November 2017.

2 The concepts 'findings' and 'results' are used interchangeably.

3 Implementation means the application or use of practice recommendations emanating from doctoral theses.

4 Dissemination refers to adapted knowledge transfer to targeted audiences.

5 Race: A - African, C - Coloured, W - White ; Gender: M - Male, F - Female.

6 University: UFH - University of Fort Hare, Wits - University of the Witwatersrand, NWU - North-West University, UP - University of Pretoria, UCT - University of Cape Town, UJ - University of Johannesburg.

7 Shebeen in South Africa refers to an informal (private house) drinking place in a township.

8 Iinethiwekhi zophando is isiXhosa for research networks.

9 Indaba refers to consultative discussions among role players