Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.54 n.1 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/54-1-615

ARTICLES

Let's talk about divorce - men's experiences, challenges, coping resources and suggestions for social work support

Mr Reginald Phumlani MnyangoI; Professor AH (Nicky) AlpaslanII

IStudent development advisor providing social work support to student bursary recipients of the Rural Education Access Programme and a former Master's student at the Department of Social Work, University of South Africa

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. <Alpasah@unisa.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

There is a lacuna in the body of knowledge, from social work specifically, on the topic of men and divorce. This prompted the researchers to embark on a qualitative research journey with the aim of exploring men's experiences of divorce, the challenges they faced and their coping strategies, and to gather suggestions for social work support. This paper reports the findings and conclusions based on the interviews conducted with 12 divorced men. In addition, recommendations are put forward.

INTRODUCTION

Divorce is likely to affect negatively the divorcee's life physically, psychologically, emotionally, socially, legally, economically, relationally and spatially. As an event, divorce may be accompanied by multiple losses at all these levels (Baum, 2003:37; Bickerdike Gee, Ilgauskas, Melvin & Hearn, 2003:1; Corcoran, 1997; Da Costa 2007; King, 2008; Kurgan, 2010).

The literature consulted seems to indicate that, for a number of reasons, men seem to find it more challenging, emotionally and psychologically, to process their divorce experiences.

• Comparing divorced men and women, men appear to find it more difficult, or even unacceptable, to articulate their deepest feelings, worries, fears, insecurities, emotional pain and grief associated with the losses resulting from divorce (Abulatia cited in Human, 2006:10; Lai, Hsiao & Chen, 2010:166-167). This, according to Corcoran (1997), may be attributed to the fact that pockets of society still uphold the traditional constructs of masculinity, to the detriment of men's mental health, which dictate to men that they should 'support' and 'protect' as part of their marital role, with the result that it is often difficult for them to show their emotional side in public (Baum, 2003:43; Baum, 2004:174; Scourfield & Evans, 2015:381).

• Men are less prone to reach out for help with the pain and stress arising from separation and divorce partly because of the "men-must-be-strong" ethos maintaining that men who seek professional help are weak, vulnerable and incompetent (Baum, 2004:174; Vukalovich & Caltabiano, 2008:148).

• Married men have fewer confidants in whom to confide. For married men, more than for married women, the marital relationship is more likely to be the primary source of emotional nourishment and their marital partner their only primary confidante (Baum, 2004:177; Scourfield & Evans, 2015:382). However, after divorce they lose this, whereas women could have a wider circle of confidantes to whom they can turn. Women have a greater propensity to forge close relationships with their friends, who would provide solace and to whom they would go to seek post-divorce counsel. Divorced men, however, are less likely to have a close friend to whom they can talk about their feelings and frustrations (Clarke-Stewart & Brentano, 2007:92; Scourfield & Evans, 2015:382-383).

• These reasons exacerbate divorced men's post-divorce psychological adjustment in terms of managing the distress caused by the divorce and re-establishing a lifestyle independent from the former spouse with a social support system (Sakraida, 2008:871). In turn, this tendency of divorced men to suppress their emotions and shy away from reaching out for help plays a major role in the development and prolongation of depression (Bickerdike et al., 2003:9; Lai et al., 2010:166;). Suicide ideation and completion is an elevated risk factor in men after divorce and separation (Human, 2006:47; Kölves, Ide & De Leo, 2011:155-156; Scourfield & Evans, 2015:380). Men respond to the multiple losses resulting from the divorce by way of "acting out ... [and] increased activity, especially throwing themselves into their work, hobbies and social life; by somatisation, and/or self-medication with alcohol and drugs, and they are more likely than women are to replace their marital partner with other sexual partners" (Baum, 2004:178, 179) - engaging in high-risk sexual behaviour (Bickerdike et al., 2003:7; Lai et al., 2010:164-1675).

Divorced fathers tend to mourn the loss of their ex-wives considerably less than they mourn the loss of their children and of their home, family life and routine. These are the symbols of family life - their workplace, coming home to a cooked meal, pulling into the driveway and feeling proud of owning a beautiful home (Baum, 2004:179).

Against this introductory background, the researchers noticed that the topic of men and divorce has not been researched substantially (Baum, 2004:176; Human, 2006:2-3, 41; Treiman et al. cited by Everett, Lee & Nichols 2006:141-142;). Human (2006:41), who undertook a research project of a limited scope in the field of psychology on the topic "Three men's experience of their journey to and through divorce, in Pretoria, South Africa", postulates that very little research has been carried out, specifically focusing on the problems and concerns encountered by men during divorce and afterwards. He also cites Winn (Human, 2006:2-3), who points out that while many books and research articles had been published about women and divorce, and even more on children and divorce, a smaller number of publications have focused on men and divorce, and even fewer have focused purely on their experiences of divorce. Baum (2004:176), writing from a social work perspective, also refers to this paucity in literature and research by noting that the emotional losses experienced by men who had gone through a divorce were been inadequately reported. In addition, very little has been published to date on therapy with divorced men. In response to this, Baum (2004:180 and 178) recommends the following: "Because men seek little help in general and with divorce in particular . help must be offered to them . Mourning these losses [referred to above] is considered essential to the completion of psychological separation that is so important to the divorced individual's functioning and emotional adjustment. Failure to complete such morning has been seen as contributing to on-going spousal conflict during and after the divorce process, as well as to the disengagement of some divorced fathers from their children".

In responding to this lacuna in the body of knowledge on the topic of men and divorce, the researchers embarked on a research journey with the aim of exploring men's experiences of divorce, the challenges they faced and their coping strategies.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Schlossberg's (1981) framework or model for analysing human adaptation to transition, or as it is also commonly referred to, the Transition Process Model (Schlossberg et al. in Sakraida, 2008:872), was selected as the theoretical framework. By looking at divorce through the lends of the Transition Process Model, divorce can be described as a stress-inducing event (Howard in Welfel & Ingersoll, 2001: 32-33; Sakraida, 2008:872), resulting in "a change in assumptions about oneself and the world and thus requires a corresponding change in one's behaviour" (Schlossberg, 1981:5). The divorce ignites a transition process, necessitating from the divorcee an appraisal of this stressor (or the situation) and a review of both personal resources (referred to as the self) and a convoy of support resources (referred to as social support), as well as coping strategies (referred to as strategies) for adapting to the situation (the divorce) and its related challenges (Sakraida, 2008:873). This transition stage, according to Schlossberg (1981:6), is a phase marked by personal and relational changes, rich in feelings and emotional reactions, and adaptation to transition is the process during which an individual moves from being totally preoccupied with the transition (the divorce) to integrating the transition into his life (Sakraida, 2008:873; Schlossberg, 1981:7). This theoretical framework will be used to present the findings and conclusions resulting from this divorce talk on men's experiences, challenges and coping resources, as well as to offer suggestions for social work support.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was adopted for this investigation, as qualitative research focuses on people's thoughts, feelings and experiences (Fox & Bayat, 2007:73; Johnson & Christensen, 2010:72). Inherent in this qualitative research approach is the collective case study and phenomenological research designs, complemented by an explorative, descriptive and contextual strategy of inquiry

In using the collective case study design instrumentally (Baxter & Jack, 2008:549-550; cf. Yin, 2003), multiple cases (i.e. divorced men) were purposively recruited with a view to gaining insight into this topic (Baskarada, 2104:5). The phenomenological research design was decided upon as phenomenology as a strategy of inquiry aims to study of the perceptions, feelings and lived experiences of individuals in relation to an event (Guest, Namey & Mitchell 2013:10-11) - in this case, men's experiences of divorce. The explorative, descriptive and contextual strategy of inquiry afforded the researchers an opportunity explore the topic and to report on (describe) the outcome of the exploration within the context and frame of reference of the lived experiences of the divorced men interviewed by focusing specifically on their experiences, challenges and coping resources in the post-divorce adjustment phase.

In order to purposively procure a sample of "information-rich" participants (Suri, 2011:65), the researcher responsible for the fieldwork engaged formal and informal networks and adopted a variety of recruitment methods (Hennink Hutter & Bailey, 2011:92-102): a website-based civil rights group, Fathers4justice; colleagues who acted as referral sources; and participants also referred to by friends.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews consisting of open-ended questions contained in an interview guide to focus the conversations with the recruited participants allowed for the required data to be collected.

In assisting with the management and analysis of the data collected, the researchers employed the steps for analysing the qualitatively generated data provided by Tesch (in Creswell, 2009:186).

In order to ensure the trustworthiness of the research findings, the researchers inter alia applied triangulation to data methods and data sources, member checks, peer consultation and an independent coder to impartially analyse the data collected (Krefting, 1991;Shenton, 2004:64-72).

The Research and Ethics Committee of Unisa's Department of Social Work granted ethical clearance for this project on condition that the ethical obligations of obtaining informed consent, anonymity in terms of participants' identities and the confidential management of information were adhered to.

BIOGRAPHICAL PROFILE OF THE PARTICIPANTS

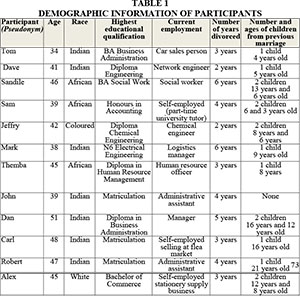

The biographical information of the 12 participants recruited (recorded by means of pseudonyms) for inclusion in this study is presented in Table 1 below. Given the fact that the researcher responsible for the fieldwork resides in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, the participants recruited were from Durban and the towns around this city.

The table shows that eight of the 12 participants were from the Indian population group; three were black African; one was white; and one coloured. Their ages ranged from 34 to 51 years. With the exception of three participants indicating their highest educational qualification as Matric, the rest had post-matric qualifications. Eleven of the 12 participants reported having children from their previous marriages. The participants' time frame since being divorced ranged from twoto six years.

THE RESEARCH FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

From the processes of data analysis by the researchers and the independent coder, seven themes were identified and presented in the next part of this article.

Theme 1: Men's accounts of the reasons that led to divorce (appraisal of the situation)

The researchers arrived at the conclusion that in very few instances did a single event stand out as a reason for the divorce. In most instances multiple reasons were given for the breaking up of the marriage. These reasons included incompatibility, a partner's unfaithfulness, domestic violence and accusations of domestic violence, changes in the partner's behaviour, the wife's refusal to go for counselling, and a lack of growth and commitment - sparking the transition.

Marital partners' incompatibility was the reason most cited for divorce (Cohen & Finzi-Dottan, 2012:594; Gigy and Kelly, 1992:173; Wolcott & Hughes, 1999:5-10), with John, Dan, Tom and Carl pointing to this as the main reason for their divorce. Themba, Alex and Mark mentioned this aspect as one of the reasons for their marriages ending in divorce. This incompatibility became manifest through the behavioural displays of the participants' ex-wives, and the fact that they and the participants had differing needs and expectations, which led to conflict within the marriage. The researchers also arrived at the conclusion that the participants felt that their needs were not considered, or remained unmet, and they felt unsupported.

The following comments are presented to underscore this aspect of incompatibility.

"I think that we discovered that we had a lot we couldn't talk about ... We argued a lot on very basic and unimportant stuff... we brought the worst out in each other ... So it was more a question of incompatibility and stuff than anything else. " (John)

''I think basically our relationship just fell. We became incompatible..." (Dan)

Unfaithfulness was the second most cited reason for divorce (Cohen & Finzi-Dottan, 2012:594; Hawkins, Willoughby & Doherty, 2012:456; Scott, Rhoades, Stanley & Allen, 2013:132). Whilst Alex and Robert pointed to their wives' unfaithfulness as one of the reasons for their divorce, Sandile and Sam provided this as the sole reason.

"I discovered that my wife was cheating ... she never had a problem, but all of a sudden she changed ... after tracking her for some time ... I had evidence [i.e. cell phone records] that she was actually cheating ... So I said I am not going to shed any blood [i.e. he is not going to hurt or kill anyone]. I will just have to go on with my life. " (Sandile)

"The reason for divorcing my wife was unfaithfulness ... I found out that she was in a relationship with another guy. " (Sam)

Domestic violence and accusations of domestic violence are mentioned in the literature as one of the contributors to marital disruption (Cohen & Finzi-Dottan, 2012:582-588; Bowlus & Seitz, 2006:28). This was also cited by Dave, Robert and Jeffry, who mentioned that accusations of domestic violence from their wives' side led to their marriages ending in divorce. Dave and Robert disclosed accusations made about domestic violence. Jeffry shared how his wife falsely accused him of molesting their daughter.

"She had asked me before that I must leave the house because she wants time on her own. I asked, 'Where must I go, this is my place. I have nowhere to go' ... She persisted ... Eventually, what she did [she] fabricated the story that I molested my daughter and she got a protection against me. The police asked me to leave the house ... They said, 'If you don't leave the house we will arrest you '. Later on that evening they came to arrest me . I was let out on bail, eventually the case came up and I went to court and . the case was withdrawn because of lack of evidence. From there she initiated the divorce. I still wanted to make up ... but ... she persisted that she wanted a divorce. She left the city with the kids."

Their wives' behaviour changes were cited by Jeffrey and Mark as reasons for their marriages ending in divorce. Jeffry recounted:

"I didn't want it [the divorce]. Somehow after her mother passed away, she changed, became another person ... She was going with friends quite a lot ... ladies night and was hardly at home. Things got worse when questioning her . She didn't like the idea of me questioning. I tried to explain to her that let's find a way to resolve the problem but . she was not willing to settle with me in the marriage."

Dave cited his wife's refusal to go for counselling as another contributor to his marriage ending in divorce. He related this as follows:

"Definitely, it [referring to their marriage] was not working ... despite repetitive attempts at marriage counselling ... in which she just did not want to participate at all. It's documented ... in an affidavit by the marriage counsellors that Mrs N did not want to attend sessions. I have tried every avenue to reconcile. Even . went for mediation ... she denied the mediation."

Failure to grow together as a couple and lack of commitment to investigate the marital relationship causes marriages to fail (Hawkins Willoughby & Doherty, 2012:458; Cohen & Finzi-Dottan, 2012:582-588). Alex and Themba cited this as another reason for their marriages ending in divorce. Themba spoke about this as follows:

"You have one partner committed and the other not committed ... I believe what made me fail is that I was not 100% committed, so when problems started I found it easy to end the marriage ... We did not work hand-in-hand."

Theme 2: Men's accounts of the divorce process - appraisal of the situation

As pointed out in the literature (Symoens, Bastaits, Mortelmans & Bracke, 2013:180; Duchen & Dennill, 2005:5-6), the event of getting divorced (i.e. the divorce process) is stressful, negative and conflict-laden. Except for John, this was the case for all the other participants, This corresponds with Schlossberg's (1981:6) assertion that the transition stage is rich in feelings and emotional reactions.

"It [referring to the whole divorce process] is a bad experience and I don't wish for anyone to go through it. It is ugly..." (Themba)

"It's a difficult experience, you see, very difficult to see that your marriage is ending, especially because we have children." (Sam)

[The divorce experience] was very, very hard. It became so hard that I eventually I used to drink myself to sleep - because she had custody of the kids. " (Dan)

The researchers found that the stress and conflict accompanying the divorce was heightened where children were involved, as testified to by the accounts of Sam and Dan above.

The literature also makes reference to this. Frieman (2009:166) wrote a paper based on the experiences shared by 15 divorced men who attended group therapy and found that the major cause of stress reported by fathers was the on-going concern about the wellbeing of their children. The divorce deprived them of the opportunity to be with the children on a daily basis and this caused much sadness and pain. The fathers missed the active role they played in rearing their children (i.e. bathing them, putting them to bed, cooking dinner for them, assisting them with their sport and homework).

In their research focusing on the relationship between father and child and the father's emotional wellbeing Bokker, Farley and Denny (2008:72) found that the newly divorced fathers who had frequent contact with their children had lower levels of emotional distress than those with reduced interaction and contact with their children. They interviewed 97 recently divorced fathers. Marital breakdown changes the relationship between the father and the child, this being particularly true for non-custodian fathers. Fathers without full custody are challenged to find ways of developing and sustaining relationships and communication with children who live apart from them (Bokker et al., 2008:62).

The researchers found that it was easy for the participants to disengage from their marital partners, but it was difficult to part ways with their children. In support of this finding, Baum (2003) states that divorced men have a distinct way of responding to divorce. Unlike women, men tend to start their mourning process later compared to women who react closer to the event. Men also tend to mourn the loss of their "home" and "children" more than the loss of their former spouses. Another conclusion arrived at was that the parents frequently use the children as ammunition to fight each other during and after the divorce.

With reference to the justice system in terms of the divorce proceedings and child maintenance matters, the participants experienced this system to be female dominated and biased. This resulted in negative experiences and they felt treated unfairly. Similar sentiments were expressed by the participants in Troilo and Coleman's (2012:609) study in which the nine "part-time full-time fathers" also declared that the legal system was biased against non-residential fathers. They were angry with the court system for what they perceived as unequal treatment, because they were men. They perceived the courts to be unwilling to assist them to see their children more and expressed the opinion that they were unfairly punished by the court system in terms of the large child-support payments they had to make. Troilo and Coleman (2012:609) note that the "one father equated his experience with the court to feeling like a racial minority who has been discriminated against".

Similar sentiments were also found in the study being reported on here.

• The absence of males in the employ of the Family Advocate's office to deal with divorce and child maintenance matters, amongst other things, caused Jeffry and Dave to experience that they were being unfairly treated. In addition, the view was that custodial arrangements were concluded based on gender preference and not on good parenting skills. Dave's account underscore this, when stating:

"The system is biased towards women. The social system, the operators of the Family Advocate, social workers, is all heavily gender-biased and they favour women more than men, undoubtedly. And the numbers speak for themselves because 99% of the cases custody is given to women by virtue of the fact that they are women, not on the basis of good parenting skills, not on the basis of the best interest of the child. None!! But solely on being a woman. A burden [is placed on the father] to prove that he is the good father whereas by default a woman is assumed to be a good mother. Which is unfair on the child, it's unfair on the relations... "

• Similar to the court system, social work itself is a female-dominated profession, which turned out to be a threatening factor for participants in that it is gender biased and does not serve the best interest of the child. In addition, the prevailing view was expressed by Dave, namely that social workers appeared to lack adequate skills needed for divorce mediation and conflict resolution.

"... the social workers are in my experience uneducated, of low pay grade because of their uneducatedness . and they have no skills when it comes to resolving family conflict. Ninety percent of the Family Advocate's Office and the social workers ' office are staffed by females. There is no balance and equality there to give a man's point of view. There is no man counsellor that understands men's mentality [i.e. how a man thinks and feels]. A man has to speak to a female who has a female ideology. All women have to do is to walk in there with the baby on the hip crying her eyes out, using their sympathy and manipulating it to maximum game so she occupies the position ofpower."

• The participants held the view that, in the divorce and child maintenance court, during the court hearings men were not given equal time and opportunity to present their case or side of the story. The men were convinced that the women received preferential treatment because they were women and expressed their emotions freely. Jeffry attested to this when stating:

"As far as the magistrate, she is biased towards the maternal parent, the lady. She doesn't consider my experiences. What matters the most is what the mother tells. "

• The perception prevailed, especially with Jeffry and Sandile, that the way in which child maintenance matters were resolved favoured the ex-wife; how it was calculated was unfair and this led to great dissatisfaction. Sandile recounted: "I was called in for maintenance ... One thing I found ... the magistrate, a woman ... was biased towards my ex-wife." Later, he commented on the issue of maintenance:

"I had to bring all the expenses together with my salary advice; I had also to bring my new wife's salary advice. For my new wife now to pay for another woman's life and I think that's very much unfair. However, the magistrate said my new wife doesn't have responsibilities because she doesn't have a child. So now she is made to pay for another woman's life. And that's very disturbing ... it nearly affected our marriage [with the second wife] because at some stage she even wanted to go to court. I said no, we will get through this. So the divorce matter is a drawback."

• Tom's experience-based perception was also that the court system fell short when assessing the psychological condition of men who could not see their children every day. This was not considered either when deciding on the fathers' access to their children. He spoke about this along the following lines:

"I don't think that Family Advocate or the justice system really analyses the psychic of a man that's in this situation where he can't see his family that he is bonded with because of laws and . preference being given to the mother. He cannot father them because the mother has the control."

Theme 3: Emotional reactions to and feelings experienced after the divorce

The researchers found that as a result of the specific events and losses brought about by the divorce, the participants did not experience just one emotion, but had many different feelings and emotional reactions after the divorce (discussed below). Some described these as "mixed", whereas others identified a number of specific feelings and emotional responses, all of which could be labelled as negative. This observation is confirmed in the literature consulted, pointing to the fact that divorce has the propensity to generate these negative feelings and emotions (Gaffal, 2010:47; Yárnoz, Plazaola & Etxeberria, 2008:295-296).

For Alex, Robert, Sandile, Sam and Themba, who were cheated on by their ex-spouses, feelings of anger, betrayal, confusion and sadness were at the forefront, as also found in other studies reporting on the same matter (Gaffal, 2010:47; Rye, Folck, Heim, Olszewski & Traina, 2004:32; Yarnoz et al., 2008:295-296). Sam's account encapsulated the smorgasbord of feelings and emotional reactions alluded to above:

"I experienced anger because she betrayed me and what she did destroyed my dignity [i.e. his wife was having an extra-marital affair] ... My trust for women was damaged. I always thought I could trust women I met at church but after what my ex-wife did, I couldn't trust any woman ...I was confused and sad."

The participants who felt that the justice system had treated them unfairly in relation to the divorce and child maintenance matters, in that they were gender biased, not giving the men a fair hearing and not serving the interests of the child, were very upset and angry. This led them to doubt and mistrust of the decisions taken by the justice system. David poignantly summed it up (i.e. that he experienced the latter system to be biased and favouring the woman's version in divorce matters): "... we [referring to men] do get angry particularly with regard to the justice system ".

Feelings of sadness were experienced by John and Sam for the fact that their marriages ended in divorce. John, who indicated incompatibility as the main reason for his divorce, stated: "I was sad that my marriage has come to an end and that I was divorced. "

Sam, speaking from a Christian point of view, confessed: "Divorce is the last option in the Bible and ...I thought it was a disgusting thing ...I was sad we did not live up to the promises we made before God."

What saddened Dan and Jeffry was the fact that the divorce resulted in their parting with the children and not from ending the relationship with the ex-spouse. Jeffry admitted: "I felt sad to be apart from them." This sadness in turn, fed into feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness and uselessness (Cohen & Finzi-Dottan, 2012:583) associated with having their children away from them.

The feelings of fear felt and spontaneously expressed by John and Alex centred on their children, because as fathers they were no longer there for their children and looking out for them. In addition, feeling like a failure was experienced. This was mainly fuelled by the inability to solve the marital problems or to make the marriage work - or to meet societal expectations of marriage as an institution. It seemed that the marriage is expected to last and when this does not happen the participants are likely to feel like they failed, not only themselves but also in their inability to meet societal expectations. Alex's account encapsulates the feelings of fear and failure alluded to above: "I think it's a sense of loss, betrayal and you doubt, question yourself as a man whether you will have a successful relationship again with a woman." In the interview, he also revealed experiencing feelings of fear: "I think also fear, lot of fear ... that fear of the future, what future is holding in for you and how it's going to affect you in the long-run run. Basically, you have to pick your life again and start from scratch. You 're back to where you were 20, 18 or 19. "

Tom, Themba and John felt relieved once the divorce was finalised. Tom "felt independent" as he experienced being dominated in his marriage. Conflict in the marriage is disruptive and the divorce can bring relief, as Themba explained:

"It was a relief for me because the relationship was difficult and tense due to a lot of conflict and arguments that I had with my ex-wife . I did experience that freedom ...It [i.e. the divorce] was a positive impact."

In spite of the freedom experienced, for Themba "It [referring to divorce] can humiliate you. In every aspect of life, it humiliates". For him there was a stigma attached to divorce - especially in relation to his religious beliefs on divorce. The fact that his wife committed adultery was a humiliating experience as they were Christians; divorce is not accepted in their religion.

Themba, Mark, Sam, Carl, Jeffry and Robert mentioned experiencing feelings of emptiness and loneliness, and highlighted this as a challenge following the divorce. The comments quoted below testify to this and their experiences are corroborated in the literature. In their study on factors related to post-divorce adjustment conducted amongst 30 divorced men, White and Esher (in Guttmann, 1989:249) reported that the biggest problem the men faced was loneliness. Wiseman (in Clark-Stewart & Brentano, 2007:23) points out that, following divorce, the process of lifestyle reorientation and defining oneself as being single can give rise to feelings of loneliness. Weiss (in Mason, Sbarra, Bryan & Lee, 2012:911) observed that the divorce process itself could also prompt feelings of loneliness.

"I think loneliness was the biggest thing ... Because now you always have someone next to you by your side and there is like no one there" (Mark)

"You are lonely and you feel like that significant part of you has been ripped off. Your family is gone! You are all by yourself. " (Sam)

"...after divorce I had nothing to look forward to. My whole life just came to a standstill." (Jeffry)

Theme 4: Men's accounts of how the divorce affected them - appraisal of the situation and the self

The divorce experience affected the participants on various levels and the majority of these affects were negative.

The stress associated with divorce affects an individual's physical and psychological health (Lawson &Thompson, 1996:264). This was also true for the participants in this study. On a physical level, four of the participants (Dave, Dan, Mark and Robert) lost weight (Sobal Rauschenbach & Frongillo, 2003: 1547). Being worried about their children's wellbeing and being separated from them led to a loss of appetite.

"I was much chunkier, much bigger. But during the process I lost about 15 kg in an instant, probably because I couldn't eat. I had no feel for eating. I was more worried about what my son is eating, what he is doing or is he okay and stuff like that." (Mark)

Jeffry and Themba gained weight, an effect that Williams, Greeno and Weng (in Umberson, Liu & Powers, 2009:328) describe as the relief of being unchained from the "hell" of the marriage. Themba's account echoed this when he mentioned:

"My marriage lasted for 2 years. In these 2 years it was a hell of a hell. There was no time I was happy while being married. So instead of losing weight after divorce I gained weight. It was a positive impact."

Dave, John and Dan in particular referred to the fact that the divorce experience affected their sleeping patterns.

"It [being divorced and being apart from his children] became so hard that eventually I used to drink myself to sleep, because she had custody of the kids ... I could not . fall asleep. I keep tossing and turning. Initially thinking about kids that I am away from them and the only way to fall asleep because the next day is work, I'll have 3 double doses and then go to bed" (Dan)

Baum (2003:40) asserts that men mourn differently from women by pointing out that, amongst other things, they respond to their loss by "self-medication with alcohol and drugs". Lawson and Thomson (1996:264) found a similar trend amongst black men from the North Central Region of the USA, with some men admitting to have used alcohol and drugs to cope with the impact of divorce.

A rise in blood pressure, becoming diabetic and developing high cholesterol levels were specifically reported by Jeffry as physical problems resulting from his divorce. These conditions are also noted in the literature (Clarke-Stewart & Brentano, 2007:76.)

On a psychological level, divorce can leave individuals feeling depressed and stressed (King & Fletcher, 2007:22-23; Santrock, 2006:489). This was true for Robert and Jeffry, who admitted: "I was suffering from anxiety and depression. I actually went for rehabilitation to the hospital."

The researchers came to the conclusion that the depression experienced was not essentially associated with the ending of the relationship with the wife, but it was a result of parting ways with the children, as this was true for Dan, Tom and Mark, who referred to this specifically.

"It [the divorce] was very depressing ... You feel a bit of loss and I used to think back a lot, what I could have done to save the marriage, what went wrong . I couldn't come to any conclusions ... My marriage wasn't successful ... I grew up with both my parents and the fact that now my children are going to grow up with single parents, it was kind of depressing. I couldn't give them what I had' (Dan)

Other scholars (Guttmann, 1989:251; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:261; Smart, 1977:77) found similar effects.

Jeffry, Carl, Alex and Mark admitted that their divorces were stressful and taxing on a psychological level. Alex expressed it as follows:

"Even at some stage you were like thinking suicide, running away, just giving up on life... lot of stress, lot of anxiety, lots of stress, lot ofpressure... "

Nine of the 12 participants interviewed reported that divorce had an extensive negative impact on them financially - a factor also noted in the literature (Zagorsky, 2005:68). It set them back financially, aggravated the loss of money already paid on property, causing a reduction in income, and a lowering in living standards. The divorce left them financially strained and cash strapped. Alex's account encapsulated this aspect:

".remember when you live in a house basically you share expenses, now you move out. Obviously you have to wrap up your estate and everything but now you've got to pay. She has to move into a smaller place, you've got to move into a smaller place. You've got to pay maintenance for them, obviously half of their school fees and extra meals. It does set you back."

In addition, the legal costs involved in getting a divorce further added to the financial strain experienced (Andreb & Hummelsheim, 2009; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:256). Jeffry, Themba, Dave and Sandile spoke unequivocally about how the legal costs related to their divorces affected them financially. Sandile encapsulated this aspect when stating:

"Economically, I lost a lot . I mean in the process of the divorce when I had to hire some lawyers. Even after the divorce was granted I had again go to court time and again for maintenance. I would argue against claims because she claim big monies and I am saying no, this I cannot afford . It was so disturbing and devastating."

With reference to post-divorce relationships, the literature indicates that post-divorce hostility amongst the partners continued and arguments were mostly focused around the children and issues related to co-parenting (Cohen, 2011:256; Margerum, Price & Windell, 2011:1). This hostility is psychologically damaging to the children and the prolonged and on-going conflict may even result in disengagement between the noncustodial parent (normally the father) and children (Ahrons & Tanner, 2003:341-342; Baum, 2004:178). This trend of continued conflict following the divorce was true for Sandile and Tom, who mentioned: "The conflict I have with my ex-wife, I don't think it will ever end. I don't think she will stop having trouble with me"

The divorce event for most people alters, disrupts, complicates and limits their continuous relationship with their children (Appleby & Palkowitz, 2007:3,7,16; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:261-262). For the non-custodial parent this results in feelings of longing, loneliness and feeling concerned and worried about the wellbeing of their children (Friedman, 2009:166). This was specifically the case for Mark and Alex. In speaking about his relationship with his children, Alex revealed: "I miss them every day. I speak with them on the phone every day, but it's not the same." Mark admitted bluntly: "... the hardest thing for me was being away from my child. "

Contrary to the literature that points to contact with their fathers ceases for many children after their parents' divorce (Appleby & Palkovitz, 2007:4; Baum, 2004:178), this study found that Sam, Dan, Dave and Sandile were making concerted efforts to continue and maintain their relationships with their children after their divorce.

"Children should come first, they are innocent and they don't even know what is happening. They want to see me and their mother together, so I have to protect them and keep them happy. Sometimes after dropping them, my ex-wife will call me and say the older one is crying for me. I have to drive back to attend the situation no matter how far I have driven. By me doing this I want to make sure that I remain connected to my children regardless of the situation. " (Sam)

''I sacrifice a lot of time to maintain and establish the bond with my child and it cost a huge amount of money ... I drive 31 km to go and pick the child up and drive another 31 km back to my house. I spend a few hours with her; we do activities like drawings ... chatting, play and all the things that allow the father to bond with his child. " (Dave)

From the accounts that Sam, Sandile, Dan and Robert shared about their relationships with the in-laws, the researchers noticed the following trend: Sam and Sandile's relationships with the in-laws were estranged, while Dan and Robert initially perceived the in-laws as being hostile and bitter towards them, but later on this conflict lessened once the in-laws accepted that they were no longer together as a couple. This trend is confirmed in the literature in that when divorce transpires, in-laws also experience loss and respond with hostility (Schwartz, 2012).

Friendships and circles of friends formed and enjoyed by the couple jointly and individually prior to the divorce are likely to decrease or disappear after the divorce (Greif & Deal, 2012:422). For Alex, Sam and Dave who had friends as couples, mentioned that their friends withdrew after the divorce, some even disappeared because they did not want to take sides with either person. Alex's account encapsulates this:

"I've got to re-establish my whole life, you know, even your circle of friends. The friends you've had, they have all fallen away, they move into a new circle of friends so you basically kind of re-establish everything in terms of your social life, in terms offriendships, in terms of your relationships with your family ... when something like this [divorce] happens your common friends seem to fall away. In our case as well, I mean I think there is one couple I still have contact with out of say five or six couples . I think what happens is they don't want to choose sides. So instead of choosing one or the other ... things just dissolve because you don't see them anymore."

Moreover, some participants felt uncomfortable about going out and they avoided people whom they knew while they were married.

Regarding the effect on the participants' residential circumstances, the following situations arose. Robert, Carl, Sandile and Themba moved out of the houses they stayed in as couples and went back to their parents. John, Dave and Jeffry remained in the houses they had shared as married couples, whilst Alex, Mark and Tom had to move from the homes they shared as couples and find other accommodation. Sam and Dan sold their houses and shared the profit with their ex-wives.

Theme 5: Challenges experienced after the divorce - appraisal of the situation

In line with the work of other scholars (Kruk in Appleby & Palkowitz, 2007:16; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:261-262), the researchers found that the greatest challenge for most of the participants in this research project centred on the children born of the marriages that had now ended in divorce, and on matters related to post-divorce parenting.

Jeffry, Sandile, Themba, Dan and Dave struggled with visiting their children because of the time allocated for visits and the distances they had to travel to see their children. It seemed especially difficult for participants who did not reside in the same province as the children. In addition, visits had to be arranged beforehand and then supervised; plans had to be confirmed with the children's mother prior to the actual visit; sometimes the mother cancels arrangements at the last minute. Some of the fathers were limited to seeing their children or conversing with them telephonically only at certain times; specific times were set for the children to come and visit them (i.e. no free access to children at any time, unlike when they were married). Sandile stated bluntly: "I have no free access to my kids."

Jeffry explained the current state of affairs along the following lines:

"I visit them every alternate weekend, Saturday and Sunday. That means I have to travel from Durban to Pretoria to go and see them. But it's not really working because of the difficulty of living in Durban . the cost involved to going to see them. It was agreed she will pay for every alternative trip that I made to see the kids. She is not doing that, she is not paying for a single trip . It's made in the court order . I arrange four weeks in advance to visit. The majority of my visits she cancels and she would say, for example: 'I am taking kids out you cannot come and visit. Or I have booked a weekend here, you cannot come and visit'. My contact rights have been denied."

Dan's challenge was that when there was conflict between his ex and him on matters of contact and visitation, the social workers were unable to assist with resolving the conflict that arose between parents.

"In fact, the social workers, both ladies, were worsening the situation. When I actually pleaded to them, I said listen it's my weekend with the kids, she refused because of A, B or C and they said she's got the right to do 11... instead of saying okay listen it's your weekend, speak to your ex-wife and any differences between the two of you must not affect the kids."

According to Dave, the Office of the Family Advocate does not have a balanced gender staff complement and perception-based experiences were that decisions taken seemed to favour mothers.

"The challenge for me at this point is access to my child. Without any solid evidence, I have to see my child on a Tuesday and the Thursday between the hours of 13:00 and 17:00. Any normal working person will not be able to do that. So that Tuesday and Thursday that's on paper are useless. That leaves me with one weekend - one day per weekend ... from 10:00-17:00 ... How can you do with one day per week? Not even a full day, that is a challenge . A father cannot be expected to spend this less amount of time with his child. They have lacking in empathy."

Theme 6: Responses to challenges experienced and coping resources used -appraisal of the support and strategies

Taking charge in the context of the Transition Process Model necessitates that one has to first take stock of both the assets and liabilities brought to this transition in terms of the situation, the self, social support and coping strategies (Schlossberg, 1981; Kotewa, 1995:48; Goodman & Anderson, 2012:11). From the participants' accounts the researchers arrived at the conclusion they took charge of their situation, in terms of post-divorce adjustment, by accessing social support and coping strategies.

Enlisting support from family and friends, the faith community and support groups assisted the participants in their post-divorce adjustment; this is confirmed in the literature (Bananno in Frisby, Booth-Butterfield, Dillow, Martin & Weber, 2012:720; Clark-Stewart & Brentano, 2007:82,84; Plummer and Koch-Hattem, 2001:528; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:267, 268).

Carl, John, Robert, Sandile, Tom and Dan enlisted the support of family members. Carl spoke about this along the following lines:

"I was very fortunate because my brothers . was very supportive. I wasn't like depressed like when I go home, then I have someone to talk to, my mother and my brothers, they were all supportive. That's why I didn't go to a very traumatising or lonely because there was someone always."

Sam, John, Robert, Tom, Themba and Dave referred to the fact that they enlisted the support of friends as a constructive post-divorce coping strategy. Sam spoke as follows about his friends' support:

"After divorce, I looked up to friends for both legal advice and emotional support. I was anxious about the court process but having friends who graduated with law and practising as attorneys helped me to ease my anxiety about the court process. Then after divorce some of my friends kept checking how I was doing . some of them used to call me, some visited me and some were still inviting me when having social functions."

In response to transitioning from being married to becoming divorced, and in reorganising their lives and moving towards adaptation or post-divorce adjustment, the participants employed various coping strategies to take charge.

Spiritual support and counselling were sought by Sam, Mark, Alex and Themba to assist with their post-divorce adjustment.

"I went ... to counselling as well. I went to see a guy and he helped me with a lot of stuff ... He is like a pastor, but also a counsellor, like a spiritual mentor. It helped me a lot. And I think just to grieve the loss because it's like somebody died, somebody you have known for a long time. " (Alex)

"As a person who is a Christian ... I relied more on the spiritual support ... I prayed about it." (Themba)

Dan indulged in drinking as way of responding to a stressful of divorce and related losses. This is a coping strategy also confirmed in the literature (Baum 2003, 40; Lawson & Thompson, 1996:264).

Sandile and Dave struck out at their ex-wives to resolve specifically the post-divorce parenting challenges. Sandile made reference to this as follows: "I couldn't hold my anger and I hit her like anything." This was during the time when the ex-wife was arguing about the clothes Sandile had bought for children that she did not like.

While the minority of the participants used these specific coping strategies which are labelled as "maladaptive" or "harmful" coping (Papalia et al., 2007:425), the majority of the participants engaged in what can be regarded as "adaptive, helpful and constructive coping" (Papalia, Sterns, Felman & Camp, 2007:425).

Jeffry, John, Robert, Alex and Dave engaged in physical activities during and after their divorces as a constructive way to de-stress.

". because of the divorce . I just did my exercise to get rid of that frustration and things like that. I was fine. I'd have my odd moments when I'd cry." (Robert)

Sam, Jeffry and Dave kept themselves productively occupied by engaging in studying further and in leisure activities to aid them in their post-divorce adjustment.

"My books are my escape ... I read a lot ... that keeps my mind occupied and it takes me a lot of time reading ... I do a lot offishing. I've got a boat - I go out to ocean for fishing. I find it very therapeutic. " (Dave)

Alex engaged in constructive self-talk, while Tom and Dan turned to the internet to learn about divorce and post-divorce adjustment. Tom spoke about this along the following lines:

''I researched the Internet a bit to learn more about divorce and I learnt about my rights and I also learn that I should calm down to deal with emotions. The internet was quite a helpful resource to understand different challenges and how to deal with them after divorce. I looked at other information particularly about the law and what my responsibilities were. I realised that I was not alone fighting with divorce and I find other resources such as Fathers4Justice website."

Jeffry joined a support group to assist him in his post-divorce adjustment:

"I ... attended a support group to help me cope with anxiety and depression. I actually went for rehabilitation at the hospital . the support group . and the psychologist equipped me with skills to cope with stress . with difficult emotions ...I benefited from being part of that support group."

Suggestions for social work support to assist men in their post-divorce adjustment

Apart from Dave, who was of the view that social workers cannot assist divorced men as they are not skilled enough to solve disputes and psychologically incompetent to comprehend the problems faced by divorce men, the participants put forward suggestions on how social workers can assist men in their post-divorce adjustment. They suggested that social workers provide post-divorce guidance and counselling on the following aspects:

• managing the stress caused by the divorce;

• dealing with the losses brought about as result of the divorce to the point of accepting them;

• restoring the self-image and self-esteem tarnished by the divorce;

• healing emotionally before venturing into a new relationship;

• relationships skills with a view to preparing them for a new relationship;

• parenting skills and skills on how to manage post-divorce parenting relationships;

• dispute- and conflict-management skills involving children following divorce;

• informing and counselling children affected by divorce by explaining how and why parents got divorced.

RECOMMENDATIONS

From the findings and the conclusions reported in this article, recommendations for further research and social work practice are offered.

Given the fact that the topic of men and divorce has not been researched substantially (Baum, 2004:176; Human, 2006:2-3, 41; Treiman et al. cited by Everett, Lee & Nichols 2006:141-142), the researchers recommend that this topic and aspects related to it be further investigated.

The negative perceptions held by some of the participants regarding the involvement of social workers in matters pertaining to their divorce led the researchers to recommend that a study be undertaken to focus on the experience-based perceptions of divorced men and women of the social workers' involvement in their divorce process.

Given some of the participants' negative experiences in relation to the officials in the employ of the Office of the Family Advocate, the researchers want to recommend a research project focusing on the topic of service users' experiences of the services offered by officials in the employ of the Office of the Family Advocate.

The formulation of a post-divorce guidance programme, not only for divorced men but for all divorced persons, is recommended based on the specific suggestions put forward by the participants in this research project.

REFERENCES

AHRONS, C.R. & TANNER, J.I. 2003. Adult children and their fathers: relationship changes 20 years after parental divorce, Family Relations, 52:340-351. [ Links ]

ANDREB, H. & HUMMELSHEIM, D. 2009. When marriage ends: economic and social consequences of partnership dissolution. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

APPLEBY, D.W. & PALKOVITZ, R. 2007. Factors influencing a divorced father's involvement with his children. Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 7. [Online] Available: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ccfs fac pubs/7. [Accessed: 17/11/2014]. [ Links ]

BASKARADA, S. 2014. Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qualitative Report, 19(24):1-18. [ Links ]

BAUM, N. 2003. The male way of morning divorce: when, what and how. Clinical Social Work Journal, 31(1):37-50. [ Links ]

BAUM, N. 2004. On helping divorces men to mourn their losses. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 58(2):174-185. [ Links ]

BAXTER, P. & JACK, S. 2008. Qualitative case methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4): 544-559. [ Links ]

BICKERDIKE, A., GEE, T., ILGAUSKAS, R., MELVIN, & HEARN, J. 2003. Men and separation: choices in tough times. Victoria (Australia): Mensline. [Online] Available: http://www.relationships.org.au/relationshipadvice/publications/pdfs/copyofmen-andseparation.pdf [Accessed 17/11/2012]. [ Links ]

BOKKER, L.P., FARLEY, R.C & DENNY, G. 2008. The relationship between father/child contact and emotional well-being among recently divorced fathers. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 45(1-2):63-77. [ Links ]

BOWLUS, A.J. & SEITZ, S. 2006. Domestic violence, employment, and divorce. International Economic Review, 47(4): 1113-1149. [ Links ]

CLARKE-STEWART, A. & BRENTANO, C. 2007. Divorce: causes and consequences. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

COHEN, L.J. 2011. The handy psychology answer book. United States of America, Canton: Visible Ink Press. [ Links ]

COHEN, O. & FINZI-DOTTAN, R. 2012. Reasons for divorce and mental health following the breakup. Journal of Marriage and Divorce, 53(8):581-601. [ Links ]

CORCORAN, K.O. 1997. Psychological and emotional aspects of divorce. [Online] Available: http://www.mediate.com/articles/psych.cfm [Accessed 26/11/2012]. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. (3rd ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DA COSTA, T.M.F. 2007. Divorce as burification: Redefining a nuclear system. Unpublished Masters Dissertation. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

DUCHEN, P.M & DENNILL, I. 2005. Dealing with children and divorce. The Fifth Annual National Conference, 15-16 September 2005. South Africa. [ Links ]

EVERETT, C.A., LEE, R.E. & NICHOLS, W. 2006. When marriages fail: Systemic family therapy intervention and issues. Binghamton: Haworth Press. [ Links ]

FOX, W. & BAYAT, M.S. 2007. A guide to manage research. Cape Town: Juta & Co. Ltd. [ Links ]

FRIEDMAN, B.B. 2003. Helping professionals understand the challenges faced by noncustodial parents. Journal of Divorce & remarriage, 39 (1-2): 167-173. [ Links ]

FRIEMAN, B.B. 2002. Challenges faced by fathers in a divorce support group. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 37(1/2): 163-173. [ Links ]

FRISBY, B.N., BOOTH-BUTTERFIELD, M., DILLOW, M.R., MARTIN, M.M. & WEBER, K.D. 2012. Face and resilience in divorce: the impact on emotions, stress, and post-divorce relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(6):715-735. [ Links ]

GAFFAL, M. 2010. Psychosocial and legal perspectives of marital breakdown: with special emphasis on Spain. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

GIGY, L. & KELLY, J.B. 1993. Reasons for divorce: perceptions of divorcing men and women. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 18(1-2): 169-188. [ Links ]

GOODMAN, J. & ANDERSON, M.L. 2012. Applying Schlossberg's 4-S transition model to retirement. Career Planning and Adult Development Journal, 28(2):10-20. [ Links ]

GREIF, G.L & DEAL, K.H. 2012. The impact of divorce on friendships with couples and individuals. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(6):421-435. [ Links ]

GUEST, G., NAMEY, E.E. & MITCHELL, M.L. 2013. Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GUTTMANN, J. 1989. The divorced father: A review of the issues and the research. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 20(2):247-261. [ Links ]

HAWKINS, A.J., WILLOUGHBY, B.J. & DOHERTY, W.J. 2012. Reasons for divorce and openness to marital reconciliation. Journal of Divorce & Marriage, 53(6):453-463. [ Links ]

HENNINK, M., HUTTER, I. & BAILEY, A. 2011. Qualitative research methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HUMAN, W.J. 2006. Three men's experience of their journey to and through divorce: the unheard songs. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Masters Dissertation) [ Links ]

JOHNSON, B. & CHRISTENSEN, L. 2010. Education research: qualitative, quantitative and mixed approaches. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

KING, A., & FLETCHER, R. 2007. Re-engaging separated fathers with their children after contact has broken down. Children Australia, 32(3):21-28. [ Links ]

KING, G. 2008. The silent screams of divorced men. [Online] Available: http://www.joymag.co.za/mag/20-2008/20-2008-silent.php. [Accessed 26/11/2012]. [ Links ]

KÖLVES, K., IDE, N. & DE LEO, D. 2011. Marital breakdown, shame and suicidality in men: a direct link? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(2):149-159. [ Links ]

KOTEWA, D. 1995. Transitions and adaptations: theory and thoughts to ponder. Colorado, Hall Director of Braiden Hall at Colorado State University. [ Links ]

KREFTING, L. 1991. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3):214-222. [ Links ]

KURGAN, V. 2010. Dealing with loneliness after divorce. [Online] Available: http://www.articledashboard.com/Article/Dealing-With-Loneliness-After-Divorce/-1890378. [Accessed 27/11/2010]. [ Links ]

LAI, Y., HSIAO, F. & CHEN, Y. 2010. Somatization of loss of fatherhood: a case study of a Chinese man with major depression. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 18(2): 163-171. [ Links ]

LAWSON, E.J. & THOMPSON, A. 1996. Black Men's perceptions of divorce-related stressors and strategies for coping with divorce: An exploratory study. Journal of Family Issues, 17(2):249-273 [ Links ]

MARGERUM, J., PRICE, J.A., & WINDELL, J. 2011. Take control of your divorce: strategies to stop fighting & start co-parenting. Atascadero, California: Impact [ Links ]

MASON, A.E., SBARRA, D.A., BRYAN, A.E.B., & LEE, L.A. 2012. Staying connected when coming part: the psychological correlates of contact and sex with an ex-partner. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31(5):488-507. [ Links ]

PAPALIA, D.E., STERNS, H, FELMAN, R. & CAMP, C. 2007. Adult development and aging. New York: McGraw-Hill [ Links ]

PLUMMER, L.P. & KOCH-HATTEM, A. 2001. Family stress and adjustment to divorce. Family Relations, 35:523-529. [ Links ]

RYE, M.S., FOLCK, C.D., HEIM, T.A., OLSZEWSKI, B.T. & TRAINA, E. 2004. Forgiveness of an ex-spouse: how does it relate to mental health following a divorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 41(3/4):31-51. [ Links ]

SAKRAIDA, T.J. 2008. Stress and coping of midlife women in divorce transition. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 30(7):869-887. [ Links ]

SANTROCK, J.W. 2006. Life-span development. Boston: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

SCHLOSSBERG, N.K. 1981. A model for analyzing human adaption to transition. The Counselling Psychologist, 9(2):2-18. [ Links ]

SCHWARTZ, A. 2012. The impact of divorce on families. [Online] Available: http://www.mentalhelp.net/poc/viewindex.php?idx=119&d=1&w=5&e=46389 [Accessed 25/02/2012]. [ Links ]

SCOTT, S.B., RHOADES, G.K., STANLEY, S.M. & ALLEN, E.S. 2013. Reasons for divorce and recollections of premarital intervention: Implications for improving relationship education. Couple and Family Psychology, 2(2):131-145. [ Links ]

SCOURFIELD, J. & EVANS, R. 2015. Why might men be more at risk of suicide after a relationship breakdown? Sociological insights. American Journal of Men's Health, 9(5):380-384. [ Links ]

SHENTON, K.A. 2004. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects, Education for Information, 22:63-75. [ Links ]

SMART, L.S. 1977. An application of Erikson's theory to the recovery-from-divorce process. Journal of Divorce, 1:1, 67-79. [ Links ]

SOBAL, J., RAUSCHENBACH, B., & FRONGILLO, E.A. 2003. Marital status changes and body weight changes: a US longitudinal analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 59: 1543-1555. [ Links ]

SURI, H. 2011. Purposive sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal, 11(2):64-75. [ Links ]

SYMOENS, S., BASTAITS, K., MORTELMANS, D. & BRACKE, P. 2013. Breaking up, breaking hearts? Characteristics of the divorce process and well-being after divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54(3):177-196. [ Links ]

TROILO, J. & COLEMAN, M. 2012. Full-time, part-time full-time, and part-time fathers: father identities following divorce. Family Relations, 61:601-614. [ Links ]

UMBERSON, D., LIU, H. & POWERS, D. 2009. Marital status, marital transitions, and body weight. Journal of Family Health and Social Behaviour, 50(3):327-343. [ Links ]

VUKALOVICH, D. & CALTABIANO, N. 2008. The effectiveness of a community group intervention program on adjustment to separation and divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 48(3/4): 145-186. [ Links ]

WELFEL, E.R. & INGERSOLL, R.E. 2001. The mental health desk reference. New York: John & Wiley sons, Wiley eBooks. [ Links ]

WOLCOTT, I. & HUGHES, J. 1999. Towards understanding the reasons for divorce. Working Paper No.20. Australian Institute of Family Studies. [ Links ]

YÁRNOZ, S., PLAZAOLA, M. & ETXEBERRIA, J. 2008. Adaptation to divorce: An attachment-based intervention with long-term divorced parents. Journal of Divorce & Marriage, 49(3-4):291-307. [ Links ]

YIN, R.K. 2003. Case study research: design and methods, (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

ZAGORSKY, J. L. 2005. Marriage and divorce's impact on wealth. Journal of Sociology, 41:406-424. [ Links ]