Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 n.4 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-598

ARTICLES

The challenge to promote social and economic equality in Namibia through social work

Ms Peggie Chiwara; Prof Antoinette Lombard

Department of Social Work & Criminology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Social work is called upon by the Global Agenda for Social Work and Social Development to promote a more just society. Social welfare services in Namibia are not aligned with the country's vision to significantly reduce inequalities by 2030. The absence of a legislative mandate is key to social work's challenge to shift from a focus on primarily psycho-social service delivery to engaging in social and economic justice issues. It is recommended that the Namibian government formalise its adoption of a developmental social welfare policy in order to create an enabling environment for social work to promote social and economic equality.

INTRODUCTION

Social workers worldwide are urged to intensify efforts to promote social and economic equality with a view to enhancing social justice, human rights and sustainable development (International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW), International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) & International Council on Social Welfare (ICSW), 2012). This shared objective is set against a backdrop of an unprecedented increase in social and economic inequalities between and within countries (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2013). Though classified as an upper-middle-income country, Namibia is also ranked amongst the top most unequal countries in the world, evidenced by the fact that the wealthiest 5 percent of Namibians control 70 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP), whilst the poorest 55 percent control only 3 percent of GDP (World Bank, 2016). Income inequality translates into inequalities in various other spheres of life that limit opportunities and access to social, economic and political resources for a large fraction of the population (UNDP, 2013). In the light of widening inequalities, Namibia adopted the Vision 2030 Policy Framework for Long-term National Development, as a plan to significantly reduce inequalities and move the country up the scale of human development by 2030 (Republic of Namibia, 2004). Eliminating poverty and inequality, preserving the planet and creating inclusive and sustainable economic growth all fall within the wider framework of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (United Nations, 2015). The paper reports on a study whose aim was to examine how social workers in Namibia are contributing towards social and economic equality. The paper begins with an outline of the political, socio-economic and social policy contexts in Namibia and their implications for social work practice. This is followed by a discussion of the study's methodology and a presentation of the findings. Conclusions are then drawn and finally recommendations are made on how social work can promote social and economic equality.

The political, socio-economic and social policy contexts in Namibia

Namibia is geographically a vast country covering an area of 824 116 square kilometres. Yet it is one of the smallest countries in Africa in terms of its population size of 2.1 million people (Republic of Namibia, 2011). The country emerged from a long history of subjugation under colonisation and apartheid. In 1884 it became a German colony. After Germany's withdrawal in 1919, the then League of Nations assigned the Union of South Africa a mandate to govern Namibia with a view to promoting the wellbeing of its people and their education towards self-governance (Matz, 2005). Contrary to the terms of its mandate, South Africa introduced an apartheid system of governance that disenfranchised the Namibian people, resulting in deeply embedded levels of extreme poverty and inequality. Although social work was introduced in Namibia in the 1950s as a response to unmet welfare needs (Ananias, Black & Strydom, 2017), practice during this time adopted a remedial, curative and maintenance stance (Republic of Namibia, 2008). Social work also operated within an unjust social welfare system that promoted inequalities by rendering superior services to the White population (Devereux, 2001). With time, the apartheid government exacerbated social welfare inequalities by creating eleven ethnic social welfare administrations known as second-tier authorities, which all ran parallel programmes for each ethnic group based on differentiated budget and resource allocations (Hopwood, 2005; Republic of Namibia, 2008). Thus, at independence in 1990, Namibia inherited deliberately tailored social and economic inequalities and a very fragmented social welfare sector. Unifying this divided social welfare sector and eliminating inequalities in social welfare provisioning were some of the major tasks confronting the new democratically elected government. An outcome of this process was the consolidation of the eleven social welfare administrations under one ministry, namely the Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS) (2010) (Republic of Namibia, 2014).

A few years after independence Namibia became party to the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development, which commits governments to addressing the structural causes of poverty, unemployment and social exclusion with a view to promoting social development, social justice and human wellbeing for all (United Nations, 1995). The adoption of the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development also influenced the advancement of developmental social work practice in many African countries (Gray, Agllias, Mupedziswa & Mugumbate, 2017). In keeping with this regional trend Namibia, through the MoHSS, initiated the process of formulating the country's developmental social welfare policy with a view to coping with the twin challenges of addressing past disparities whilst meeting new needs and demands in the democratic era (Patel, 2015). The policy development process culminated in a draft green paper in 1996 and a draft white paper on social welfare in 1999 (MoHSS, 2010; Republic of Namibia, 2014). It is argued, however, that this policy process quickly fizzled out; the policy drafts became inapplicable and were thus shelved as a result of an institutional situation that arose after the government redistributed the social welfare mandate amongst five ministries (Masabane, & Wiman, 2006; MoHSS, 2010; Republic of Namibia, 2008). Presently, these five ministries respectively have mandates for child welfare and gender-based violence (GBV); youth welfare; medical social work and social services to persons above the age of 18; war veterans' welfare and correctional services. The MoHSS (2010) and the Republic of Namibia (2008) report that the splitting of the social welfare mandate was not accompanied with clear-cut guidelines on the roles and responsibilities of each ministry, which often results in ministries duplicating services, confusion, inefficiency and ineffectiveness in meeting social welfare needs. In 2013 the MoHSS attempted to re-ignite the developmental social welfare policy development process resulting in the compilation of a Draft Situational Analysis on Social Development in Namibia (Republic of Namibia, 2013; 2014). However, at the time of writing this paper, the policy process had not advanced significantly.

While 500 registered social workers (Tjihenuna, 2015) for a population of just over 2.1 million people appears to be adequate, the vastness of the country, the high level of inequality and the ongoing impact of droughts that exacerbate existing poverty emphasise the shortage of social workers in Namibia. This number, however, includes social workers who are registered but not practising because they have retired, are employed in non-social work sectors or for other reasons, as the number of social workers practising in Namibia is much lower. The public sector through the MoHSS and the Ministry of Gender Equality and Child Welfare (MGECW) (2010) is the predominant employer of social workers, with very few social workers employed in the non-governmental social welfare sector. However, in 2013 a mere 156 social workers were employed in the public sector (Republic of Namibia, 2013). The University of Namibia (UNAM) is the country's only social work training institution. It offers Bachelor of Arts Honours, Master's and PhD degree programmes in Social Work through its Windhoek campus. The Social Work and Psychology Act 6 of 2004 provides for the establishment of a Social Work and Psychology Council to regulate the registration and practice of social workers, psychologists and social auxiliary workers. Whilst the registration and practice of social auxiliary workers is provided for by law, to date there are no institutions in the country that train or employ social auxiliary workers. It is well recognised in neighbouring South Africa that social workers require the support of social auxiliary workers, as a skills shortage seriously undermines social work's capacity to respond to social change and delivery on social and economic development goals (Lombard, 2008).

METHODOLOGY

The study utilised a qualitative research approach and, in alignment with the exploratory purpose of the study, used an instrumental case study to explore new knowledge (Fouché & Schurink, 2011:321) on social work in Namibia in relation to promoting social and economic equality. Purposive sampling (Neuman, 2011) was applied to select 10 social workers from three government ministries, a parastatal and a faith-based organisation (FBO). Participants had to directly render social work services to poor and marginalised communities in a range of social welfare service organisations in urban, semi-urban and rural areas. One-on-one interviews, guided by a semi-structured interview schedule (Neuman, 2011), served as the primary data-collection method for the study. Guided by the principle of data saturation (Bowen, 2008; Guest, Bunce & Johnson, 2006), 10 participants were sufficient as interviews began yielding repetitive data. Participation in the study was voluntary and all participants gave their informed consent to be interviewed. Depending on each participant's geographical location, interviews were conducted either face to face or telephonically. Trustworthiness of data was increased by the audio-recording of interviews, which enhanced the accuracy of data transcriptions. Furthermore, participants were granted the opportunity to read through a verbatim transcription of their own interviews with a view to verifying the accuracy of the information (Ivankova, 2015). Creswell's (2014) thematic data-analysis process was used to analyse the research data. Data from the one-on-one interviews were corroborated with an analysis of participants' job descriptions. However, a limitation was placed on the richness of the corroborated data as a result of one organisation denying the researchers access to participants' job descriptions, citing confidentiality as the reason. The University of Pretoria provided ethical clearance for the study.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

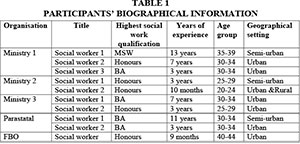

Participants' biographical information is first presented, followed by the themes that emerged from the research data.

Biographical information

Nine females and one male participated in the study, which reflects the gender composition in social work. In view of the fact that the public sector is the largest employer of social workers in Namibia, the majority (seven) of participants worked in three government ministries, two worked for a parastatal and one for an FBO. Participants worked directly with service users from poor and marginalised communities in various urban, semi-urban and rural contexts in four of Namibia's 14 administrative regions. Six of the participants worked in urban areas, whilst three worked in semi-urban areas and one worked in both an urban and a rural area. Participants were relatively young adults, which reflects the predominantly youthful population of social workers in Namibia. In line with their relatively young age groups, participants' years of social work experience ranged from less than a year to 13 years. Of the 10 participants, four held a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in Social Work qualification from UNAM. This qualification did not offer developmental social work training and was consequently replaced by the Bachelor of Arts in Social Work (Honours) in 2010, which offers an introductory social development module in the second year of training. Whilst all five participants with Honours degrees received developmental social work exposure through their undergraduate social work training, four of them were trained at UNAM and one was trained at a university in Zimbabwe. The only participant with a Master's in Social Work (MSW) qualification had a specialisation in Social Development, also from a Zimbabwean university. Participants' biographical information is summarised in Table 1 below. In order to maintain the anonymity of participants, their names and the names of their organisations do not feature in the discussion of findings. However, in the case where more than one social worker from the same organisation participated in the study, a number is used to differentiate them within their respective organisations.

Themes

The study's data produced five themes related to the challenge for the social work profession to promote social and economic equality in Namibia. The themes include: a limited number of social workers, limited accessibility to social welfare services, poor collaboration in social welfare service delivery, inadequate training in developmental social work, job descriptions that are not oriented towards developmental social work practice, and a lack of funding for developmental social welfare interventions. In the following discussion the findings on the study's themes are confirmed by participants' voices, information from participants' job descriptions and with reference to the literature.

Theme 1: Limited number of social workers

Whilst social works are the predominant providers of social welfare services, participants were of the view that there are a limited number of social workers to deliver on the social welfare mandate. Consequently, social workers were often overwhelmed by heavy workloads that made their contributions appear somewhat insignificant, considering the demand for social welfare services.

"I'm the only social worker here but … I really feel that we have to be … even 10 of us to divide the workload. [Consequently]… one ends up not giving sufficient support or help to the clients, although you are trying." [Social worker 3, Ministry 1].

"Being the only social worker at this organisation…the burden of work is very high." [Social worker, FBO].

"The ratio of clients to social workers is not balancing … with the amount of caseloads that an individual social worker has, it might not be possible to really give satisfactory service … most of the time is spent on report compiling and typing." [Social worker 1, Ministry 2].

"I serve the whole constituency [on my own] … the [other] problem is that I have to help out, I am relieving another social worker from another constituency because there is no other social worker there … Like now I am on study leave, the clients go to the office looking for my help but I am not there, so they have to come back again. And these are the people that already don't have so much." [Social worker 2, Ministry 2].

Participants' job descriptions from Ministry 1 and from the FBO corroborated the finding on the limited number of social workers in Namibia. They respectively cite as challenges a shortage of registered social workers in the public sector and being the only social worker appointed in an organisation. The limited number of social workers permeates many facets of social welfare service delivery that should ideally target social and economic inequality. For instance, with the exception of the Khomas region, where three public sector social workers are assigned to deliver on the gender equality mandate, only one social worker is allocated to each of the country's other regions (Kangootui, 2017). In addition, many children in communities that have been worst hit by four years of persistent drought suffered violation of their right to social grants because of the limited availability of social workers to undertake assessments and reviews for child grant eligibility (United Nations Children's Fund, 2017). Namibia has over the years increased its enrolment of student social workers at UNAM from an average of 18 students per year in the early 2000s to as many as 60 students in 2009 (Ananias & Lightfoot, 2012:198). The country also, to a limited extent, recruits social workers from neighbouring Southern Africa to fill vacant social work positions. However, much more is required to ensure that the gaps in social welfare service delivery are filled.

Theme 2: Limited accessibility to social welfare services

The findings also reveal a limited accessibility to social welfare services as social workers are often not found in close proximity to many rural communities.

"You find someone … has to travel maybe like 180 kilometres to [access services] but they don't have transport money for a bus to reach all the way." [Social worker 2, Ministry 3].

"The areas are so far from each other, there is no [cellular] network. There is no … transport in the community … for the people. I know it's challenging." [Social worker 2, Ministry 2].

Delivering social welfare services in Namibia is often a mammoth task because of the vastness of the country and considering the fact that the Namibia's population density of 2.9 people per square kilometre makes it the 5th smallest population density in the world (Porter, 2016). Accessibility to social welfare services is also compounded by the fact that social workers are often assigned to work with rural constituencies but have their offices in town. However, many social workers do not reach out to provide services to the most remote rural areas, as this requires transport and such areas are more difficult to get to (MGECW, 2010:101).

Theme 3: Poor collaboration in social welfare service delivery

Participants' views reflect poor collaboration in social welfare service delivery, as social welfare organisations often work in silos, the result being a duplication of services and a failure to adequately respond to social welfare needs. The need for coordination to improve service delivery is clearly reflected in the following views:

"… the work that we do … is within this organisation but not … with other social workers." [Social worker 2, Parastatal].

"… social workers are scattered in different ministries so we end up duplicating services." [Social worker 2, Ministry 1].

"[If] I have a client here [who is relocating to another region]. Who am I going to refer that client to in the other regions? At least if there was a colleague of mine there [a social worker from my ministry]. You know the story, I can't refer to [the ministry of] gender, gender will tell me no. [The ministry of] health doesn't do the same programmes … ." [Social worker 1, Ministry 3].

The job description from Ministry 1 listed working in professional isolation as an adverse working condition, thus pointing to the poor working relationships amongst social workers in various social welfare organisations. This view is supported by Ananias and Lightfoot (2012), who report that social workers in Namibia have traditionally had little social cohesion. The poor collaboration and coordination in social welfare service delivery is often attributed to the absence of a national social welfare policy framework (Republic of Namibia, 2008). In addition, there is no overarching coordinating body mandated to oversee social welfare provisioning in the non-governmental sector; thus this sector also exhibits a fragmented working system that often results in the inevitable duplication of programmes (Republic of Namibia, 2008). The imperative for social workers to work in unison in promoting social and an economic inequality was expressed as follows:

"We social workers … we need to make use of the platforms available like the media and … stand up together and maybe have a workshop where there are social workers only … we need to write a petition to parliament … to gather as a united front and be more vocal." [Social worker 2, Ministry 3].

"Namibian Association of Social Workers, I think we can use that platform … [to] advocate for the social economic emancipation of the vulnerable people." [Social worker 1, Ministry 1].

According to Ananias and Lightfoot, (2012) the Namibia Social Workers Association (NASWA) was re-established in 2008 after social workers felt that a professional organisation would be necessary to promote cohesion and to lobby for social workers to practise developmental social work. However, NASWA has since its re-establishment has struggled to play an active role in this regard amidst a very small social work population that is scattered across a geographically vast country. Participants confirmed this observation:

"I think the problem with NASWA is that now is the time they are starting to [revive]. It was almost dead." [Social worker 1, Ministry 1].

"[NASWA is] getting there, they are still blooming, still maturing but they are getting there." [Social worker 1, Ministry 2].

Theme 4: Inadequate training in developmental social work

The general view amongst participants was that they lack adequate training in developmental social work and this impacts on social workers' involvement and attitude towards developmental social work.

"[Social workers] … are not educated [in developmental social work thus] it's very difficult to promote social [and economic] equality ... I think the lack of involvement of social workers … in promoting this social development theory ... also has to do with the curriculum." [Social worker 1, Ministry 1].

"… to be honest … we just had social development as a module … and it was only for a semester. I don't think it was repeated … so the concept of social development is somehow there [but] I don't have much experience with it." [Social worker 1, Ministry 2].

A limited understanding of the applicability of developmental social work in statutory work with children was highlighted as follows:

"Actually [developmental social work] is not one of the things I am supposed to do … because our ministry is more like for children … maybe social workers from the Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Youth, play a role in that." [Social worker 2, Ministry 2].

Contrary to this participant's view, Lombard and Kleijn (2006) report that all social work practice, including work with individuals and statutory social work, can be applied from a developmental social work perspective. The finding that social workers in Namibia are not completely familiar with developmental social work is also noted by Ananias and Lightfoot (2012). Whilst Namibia has long subscribed to the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development, UNAM only integrated a social development module into its Social Work curriculum in 2010 and in particular only on an introductory level in the second year of study. However, outside of the formal social work training offered at UNAM, there is a lack of continual professional development training in developmental social work and social justice in Namibia (Ananias & Lightfoot, 2012). This lack of developmental social work training may explain why social workers in Namibia often do not engage in macro-level advocacy, social justice and human rights-based practice, which are all critical when promoting social and economic equality. Social workers functioning within a human rights-based approach engage in interventions that protect, promote and facilitate the rights of populations at risk of marginalisation and oppression, whilst working collaboratively with other actors at multiple levels of intervention (Patel, 2015). Developmental social work is heralded as a vehicle that social workers can use in promoting the social and economic rights of people (Lombard & Twikirize, 2014). It also provides the means through which social workers can "work together, at all levels, for change, for social justice, and for the universal implementation of human rights, building on the wealth of social initiatives and social movements" (IFSW et al., 2012:1). Thus, a lack of knowledge in developmental social work can seriously hamper social workers' capabilities in contributing to social and economic equality.

Theme 5: Job descriptions that are not oriented towards developmental social work

This theme is addressed from the perspective of participants' job descriptions, which revealed that social welfare service organisations do not require social workers to practise within an integrative framework of human rights-based practice, social and economic inclusion, partnerships and the participation and empowerment of client groups, whilst bridging the micro-macro divide, principles that are cornerstones in developmental social work practice (Patel, 2015). This finding demonstrates that social welfare organisations have not yet come on board with the government decision to adopt a developmental social work focus in line with the United Nations Copenhagen agreement (MoHSS in Ananias & Lightfoot, 2012). Across all four participants' job descriptions, the term developmental social work was mentioned only once and this was in the job description, from Ministry 1. This job description highlighted the need to provide developmental social work as the primary purpose of social workers in this ministry. Further than that, it did not assign any duties related to the principles of developmental social work practice. A common feature that resonated across participants' job descriptions was the requirement to render psycho-social services using a combination of casework, group work, community work and administration social work methods. Whilst providing psycho-social services is a traditional form of social work practice, it does not have a significant impact on addressing social and economic inequalities.

However, isolated developmental social work principles featured in three of the four participants' job descriptions. For instance, the job description from Ministry 3 required social workers in this ministry to provide rehabilitation and aftercare services that re-integrate target communities into social and economic life, and to educate target groups on their rights. The job description from Ministry 2 required social workers in this ministry to ensure that target groups are aware of their rights, whilst the job description from the FBO required social workers in this organisation to engage in macro-level practice through awareness creation, advocacy, networking and lobbying for clients' needs, elements that are crucial in human rights-based practice. South Africa, which shares a similar history with Namibia of apartheid governance, adopted the White Paper for Social Welfare (Republic of South Africa, 1997) to mandate the delivery of developmental social work practice across governmental and non-governmental organisations.

Theme 6: Lack of funding for developmental social work interventions

Whilst developmental social work utilises interventions that strengthen human and social capital, empowerment, employment, microenterprises and access to social welfare rights (Midgley, 2014), the findings show a lack of allocated funding to enable social workers to implement interventions targeted at vulnerable people. The lack of funding was an overall concern, especially for participants who received developmental social work training, as it impacted on the nature of their work.

"The money that is allocated for social welfare is the least and there is no money at the end … even to do projects." [Social worker 1, Ministry 1].

"You try to put in a programme and the [ministry] will tell you there is no money." [Social worker 1, Ministry 3].

"Funding is the biggest challenge that we are facing right now." [Social worker, FBO].

"After training, the resources for us to implement what we have been trained is a big challenge." [Social worker 2, Ministry 1].

The job description from Ministry 1 cited resource constraints as a challenge hampering the delivery of social welfare services in the public sector; however, this job description did not specify the types of resource constraints it was referring to. The lead researcher's experience working as a social worker in Namibia's public sector shows that social workers often practised without allocated funding to enable them to take on broader meso- and macro-level social injustices. A lack of financial resources could explain why social workers, although trained in developmental social work since 2010, still resort to individual counselling methods that do not significantly impact on poverty and inequality (Ananias & Lightfoot, 2012). The lack of funding for developmental social work interventions could be linked to the perception in some organisations that social welfare services expend financial resources on unprofitable work:

"This department where social workers are working … even the allocation of money is very little because they are saying … after all there is no profit … ." [Social worker 1, Ministry 1].

"So basically what challenges us is [a lack of] finances … We are being told that [our organisation] is about making money … And we in our [social work] department are giving out money." [Social worker 1, Parastatal].

The limited funding could also be linked to a lack of knowledge on the potential benefits of developmental social work, which is a departure from the remedial role that social work in Namibia has traditionally assumed. However, because of the micro-level focus that social work in Namibia has historically adopted, there is still a lack of recognition of the role that social work could play in national development.

"Social work is not yet highly recognised … a lot of organisations don't have social workers … ." [Social worker 3, Ministry 1].

According to Rwomire and Raditlhokwa (1996), a consequence of the constricted perception of social work's developmental role is that in many African countries social work does not proactively address structural sources of poverty, but operates at a passive and unambitious level of practice. However, from a social development perspective social welfare expenditure is an investment in development, national building, social cohesion and key social services that contribute to economic development (Adesiná, 2007; Patel, 2015). A key to addressing social and economic inequalities in any given country lies in conscious investments in sustainable social programmes that enhance people's welfare (Elliott, 2011; Patel, 2015).

CONCLUSIONS

The legacy of the apartheid era in terms of widespread poverty and social and economic inequality continues to challenge Namibia to this day. However, social welfare services in Namibia are not aligned with the national vision to significantly reduce inequalities by 2030. The limited number of social workers points to a lack of capacity to deliver on developmental social welfare goals. Although the case of Namibia is a special one, it is certainly not unique, as the scarcity of social workers is experienced, albeit in varying degrees, in other African countries such as South Africa, Botswana, Kenya and Zimbabwe (Department of Labour, 2008; Kang'ethe, 2014; Lombard & Wairire, 2010; Mugumbate, 2014). However, a point to note is that this limited number of social workers must not prevent Namibia from re-orienting services towards developmental social work and thus human rights-based practice and the promotion of social and economic equality. Social workers cannot realistically contribute to social and economic equality when they are not empowered to practice developmental social work. Promoting social and economic equality starts first with knowledge on human rights, particularly on what socio-economic rights are and how these relate to social work (Lombard & Twikirize, 2014). Whilst social work is embedded in human rights (Ife, 2012) and social justice (Hoefer, 2012) the study's findings indicate that social workers do not stand up for their rights and the profession's obligation to advocate for the rights of the marginalised and for social change. Social worker 2, Ministry 3 confirms this:

"Social workers [should] be vocal about social and economic injustices, they should be the voice for those who can't speak up for themselves."

Overall, the challenges facing the social work profession in Namibia in promoting social and economic equality can be attributed to a lack of a legislative mandate to shift social work practice from being merely psycho-social to prominently engaging in addressing macro-level social and economic justice issues. The lack of a developmental social welfare policy directly impacts on the poor collaboration in social welfare service delivery, a lack of training in developmental social work, a lack of allocated funding for social welfare programmes and the failure of social welfare organisations to incorporate developmental social work in social workers' job descriptions. Addressing the poor collaboration in the delivery of social welfare services is critical to a country that has so few social workers. Political involvement and commitment are necessary in any attempts aimed at promoting social and economic equality. However, the findings reflect a lack of effective organising, networking, planning, mobilisation and political skills amongst social workers (Dominelli, 2012; Rwomire & Raditlhokwa, 1996). This is seen in social work's failure to bring the government to task for not demonstrating the political will to formalise its commitment to the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development through the adoption of a developmental social welfare policy. Furthermore, social work has failed to lobby for the creation of an enabling environment for the training and practice of social auxiliary workers, with the view of complementing the social work workforce. The profession has also been silent on the lack of budgetary allocations for social work projects and the lack of training in developmental social work practice, in line with the government's expressed commitment to social development. Developmental social work training and practice in Namibia continue to be inadequate, as there is no welfare policy mandate to fully shift social work education and practice to a developmental focus. This ultimately influences the degree to which social work in Namibia will ultimately contribute to the Global Agenda for Social Work and Sustainable Development (IFSW et al., 2012) and hence the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Addressing the challenges that confront social work in Namibia promoting social and economic equality requires a strong political will. It is recommended that the Government of the Republic of Namibia formalise its commitment to developmental social work through the adoption of a developmental social welfare policy. In line with Namibia's Vision 2030, effective social policies to redress poverty, inequality and lack of opportunity are an urgent imperative as they help ensure social justice and the redistribution of resources, and also complement economic development by enhancing human capital and productive employment (Ortiz, 2007). Although, adopting a developmental social welfare policy is not necessarily the panacea for the challenges faced by the country's social welfare sector, such a policy will mandate social welfare organisations to transcend rendering psycho-social services in order to engage in macro-level practice within a human rights-based approach that advocates for social and economic justice. A developmental social welfare policy can then be used in holding the government accountable for creating and supporting an enabling environment for developmental social work practice. Such an enabling environment could include the training and recruitment of adequate numbers of social workers and social auxiliary workers, advanced developmental social work training and the allocation of sufficient and equitable funding for social welfare services and programmes.

As promoting social and economic equality calls for a united front, social workers and social welfare organisations should work in collaboration with other stakeholders in promoting the sustainable social and economic wellbeing of all members of society (IFSW et al., 2012). Working collaboratively and with proper coordination enhances the impact of social welfare service interventions in promoting social and economic equality and reduces the fragmentation and duplication of efforts (Republic of Namibia, 2014). It is recommended that UNAM extends social work training to its other campuses and also make developmental social work the integral thrust of its curriculum, so as to adequately empower social workers for dealing with social change, social development and the empowerment and liberation of marginalised groups (IFSW & IASSW, 2014). As the social work population in Namibia is quite small, social workers can find leverage in mobilising social welfare service users in social action that actively lobby government for the human and financial resources needed for promoting access to social and economic rights, as well as the finalisation of the developmental social welfare policy.

It is also recommended that NASWA should play a leading role in coordinating advocacy efforts in this direction. NASWA will also benefit from the support and strength that comes with affiliating to the International Federation of Social Workers as well as to regional social work bodies. As no national social work conferences are held in Namibia, a role is also identified for NASWA in this regard. A national social work conference could be a minor step towards strengthening working relationships amongst social workers and other partners with the view of achieving social justice and addressing Namibia's development challenges. Social workers in Namibia are also encouraged to attend regional social work conferences with a view to sharing knowledge and keeping abreast of best practice models in achieving integrated social and economic justice.

The legislative provision in the Social Work and Psychology Act 6 of 2004 that legitimises the practice of social auxiliary workers has never been implemented. The study recommends that the Namibia Social Work and Psychology Council appoints a commission to investigate reasons why an enabling environment for the training and employment of social auxiliary workers was never created. Thereafter, corrective steps could be taken to rectify the problem. The Social work and Psychology Council could also mandate continual professional development training in developmental social work. This will ensure that all social workers in Namibia receive training that empowers them to significantly contribute towards the achievement of social and economic justice.

References

ADESINÁ, J.O. 2007. Social policy in Sub-Saharan African context: in search of inclusive development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan and United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). [ Links ]

ANANIAS, J., BLACK, L.S.M & STRYDOM, H. 2017. Social work engagement in the community-based care of elders in Namibia. In: GRAY, M. (ed). The handbook of social work and social development in Africa. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

ANANIAS, J. & LIGHTFOOT, E. 2012. Promoting social development: building a professional social work association in Namibia. Journal of Community Practice, 20(1-2):196-210. [ Links ]

BOWEN, G.A. 2008. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1):137-152. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF LABOUR. 2008. Social work as a scarce and critical profession. [Online] Available: http://www.labour.gov.za/DOL/downloads/documents/research-documents/Social%20work_Dol_Report.pdf. [Accessed 04/04/17]. [ Links ]

DEVEREUX, S. 2001. IDS discussion paper 379: Social pensions in South Africa and Namibia. [Online] Available: https://www.ids.ac.uk/files/dp379.pdf. [Accessed /28/04/17]. [ Links ]

DOMINELLI, L. 2012. Green social work. From environmental crises to environmental justice. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

ELLIOTT, D. 2011. Social development and social work. In: HEALY, L.M. & LINK, R.J. (eds). Handbook of international social work, human rights, development and the global profession. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds). Research at grassroots for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

GRAY, M., AGLLIAS, K., MUPEDZISWA, R. & MUGUMBATE, J. 2017. The expansion of developmental social work in Southern and East Africa: opportunities and challenges for social work field programmes. International Social Work, 1 -14. [ Links ]

GUEST, G., BUNCE, A. & JOHNSON, L. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1):59-82. [ Links ]

HOEFER, R. 2012. Advocacy practice for social justice (4th ed). Chicago, IL: Lyceum. [ Links ]

HOPWOOD, G. 2005. Regional councils and decentralization: At the crossroads. [Online] Available: http://www.kas.de/namibia/en/publications/6975/. [Accessed 28/04 /17]. [ Links ]

IFE, J. 2012. Human rights and social work: towards rights-based practice (3rd ed). London: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS (IFSW), THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLS OF SOCIAL WORK (IASSW), & THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON SOCIAL WELFARE (ICSW). 2012. Global agenda for social work and social development commitment to action. [Online] Available: http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=60880. [Accessed 25/03/17]. [ Links ]

IVANKOVA, N.V. 2015. Mixed methods applications in action research: from methods to community action. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

KANG'ETHE, S.M. 2014. Exploring social work gaps in Africa with examples from South Africa and Botswana. Journal of Social Sciences, 41(3):423-431. [ Links ]

KANGOOTUI, N. 2017. Shortage of social workers hits GBV fight. The Namibian Newspaper, 23 March: 3. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A, 2008. The implementation of the white paper for social welfare: A ten-year review. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 20(2):154-173. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. & KLEIJN, W.C. 2006. Statutory social services: an integrated part of developmental social welfare service delivery. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 42(3/4): 213-233. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. & TWIKIRIZE, J. M. 2014. Promoting social and economic equality: Social workers' contribution to social justice and social development in South Africa and Uganda. International Social Work, 57(4): 313-325. [ Links ]

LOMBARD, A. & WAIRIRE, G. 2010. Developmental social work in South Africa and Kenya: Some lessons for Africa. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, Special Issue, (April 2010):98-111. [ Links ]

MASABANE, P. & WIMAN, R. 2006. Namibia: Social Welfare Sector Reform Implies Policy Reorientation. In: WIMAN, R., VOIPIO, T. & YLÖNEN, M. (eds). Comprehensive social and employment policies for development in a globalizing world: Report based on an expert meeting at Kellokoski, Finland November 1-3, 2006. [Online] Available: http://www.formin.fi/public/download.aspx?ID=16057&GUID=%7B042D62F4-A77D-41A3-959C-2DD14D66D30D%7D. [Accessed 01/04/17]. [ Links ]

MATZ, N. 2005. Civilization and the mandate system under the league of nations as origin of trusteeship. In: VON BOGDANDY, A., WOLFRUM, R. & PHILIPP, C.E. (eds). Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff publishers. [ Links ]

MIDGLEY, J. 2014. Social development: theory and practice. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

MINISTRY OF GENDER EQUALITY AND CHILD WELFARE. 2010. The effectiveness of child welfare grants in Namibia study findings and technical notes. [Online Available: https://www.unicef.org/namibia/MGECW_2010_Child_Grants_Report_Vol_2_Study_ findings_and_technical_notes.pdf. [Accessed 16/06/17]. [ Links ]

MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES (MoHSS). 2010. National Health Policy Framework 2010-2020. Windhoek: MoHSS. [ Links ]

MUGUMBATE, J. 2014. Promoting social work for Zimbabwe's development. In: NYANGURU, A. & NYONI, C. (eds). Promoting social work for Zimbabwe's development. Bindura: Department of Social Work Bindura University of Science Education. [ Links ]

NEUMAN, W.L. 2011. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

ORTIZ, I. 2007. National development strategies policy notes: social policy. New York: United Nations Department For Economic And Social Affairs. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2015. Social welfare and social development in South Africa (2nd ed). Cape Town: Oxford. [ Links ]

PORTER, L. 2016. Mapped: The world's most - and least - crowded countries. [Online] Available: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/maps-and-graphics/The-worlds-least-densely-populated-countries/. [Accessed 17/06/17]. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2014. Social development policy: situational analysis on social development in Namibia version 5, 4th draft, January 2014. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2013. Social development policy: situational analysis on social development in Namibia version 5, 3rd draft, March 2013. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2011. Namibia 2011 Population and Housing Census Main Report. [Online] Available: http://cms.my.na/assets/documents/p19dmn58guram30ttun89rdrp1.pdf. [Accessed 02/04/17]. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2008. Health and social services review. Windhoek: Ministry of Health and Social Services. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. 2004. Namibia Vision 2030: Policy Framework for Long-Term National Development. Windhoek: Office of the President. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 1997. White Paper for Social Welfare. [Online] Available: www.gov.za/documents/download.php?f=127937. [Accessed 03/12/17]. [ Links ]

RWOMIRE, A. & RADITLHOKWA, L. 1996. Social work in Africa: issues and challenges. Journal of Social Development in Africa, II (2):5-19. [ Links ]

SOCIAL WORK AND PSYCHOLOGY ACT 6 OF 2004 (Published in the Government Gazette, (3248) Windhoek: Government printers). [ Links ]

TJIHENUNA, J. 2015. The exodus of social workers. The Namibian Newspaper, 20 March: 6. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Online] Available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for %20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf. [Accessed 05/09/17]. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 1995. Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development. [Online] Available: http://www.un-documents.net/cope-dec.htm. [Accessed 23/02/17]. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND. 2017. Namibia humanitarian situation report- report #1. [Online] Available: https://www.unicef.org/appeals/files/UNICEF_Namibia_Humanitarian_SitRep_Feb_2017.pdf. [Accessed 16/06/17]. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME. 2013. Humanity divided: confronting inequality in developing countries. [Online] Available: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/poverty-reduction/humanity-divided--confronting-inequality-in-developing-countries.html. [Accessed 29/04/17]. [ Links ]

WORLD BANK. 2016. Namibia: poverty alleviation with sustainable growth. [Online] Available: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/EXTPA/0,,con tentMDK:20204583~menuPK:435 735~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:430367,00.html. [Accessed 04/04/17]. [ Links ]