Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Social Work

versión On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versión impresa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 no.3 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-571

ARTICLES

Revitalizing social work practice: the community development conundrum

Prof Sello Levy Sithole

Director: School of Social Sciences, Department of Social Work, University of Limpopo, South Africa. <Sello.Sithole@ul.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

This paper is an amended version of the presentation made at the Social Work Indaba held 24-26 March 2015 in Durban. The problem that was investigated is whether it is desirable to teach community development in the undergraduate social work programme. A sample of academics in the Department of Social Work at the University of Limpopo was asked to express their views on this. Another available sample of social work practitioners was asked the same question. The findings from the two samples are divergent in that the academics insisted that community development should remain part of the university social work programme, whereas young practising social workers felt that it should be discontinued.

INTRODUCTION

This paper is an amended version of the presentation made at the Social Work Indaba: "Revitalizing Social Work Practice in South Africa" held in Durban on 24-26 March 2015. Revitalisation means energising, stimulating and re-invigorating. The intention to revitalise social work practice in South Africa is a tacit acknowledgement by all concerned stakeholders that all is not well, or that there is something absolutely abominable or horrible about the social work status quo. Revitalisation may therefore entail an evolutionary and incremental change rather than a revolutionary and apocalyptic one. The choice as to which way to go depends largely on the perception and sober assessment of the social work landscape by all concerned key stake holders. As far as this author can gauge, an evolutionary and incremental change in this particular context is far more constructive and desirable than a revolutionary and dramatic one, as I will demonstrate throughout the paper in which I address the community development conundrum in South Africa.

BACKGROUND

The Social Work Indaba was held against the backdrop of several areas of concern from both (political) management of the Department of Social Development (DSD) and social workers. Some of the issues raised at the Indaba were that social workers were dissatisfied with the deployment of MECs and non-social work staff to the Department. Some of the questions raised were why deploy a nurse to the position of MEC rather than a social worker, since the latter has an understanding of the processes and challenges of the profession (Dlamini & Sewpaul, 2015). Participants were of the view that the deployment of non-social workers to key social work positions undermined social work as a profession, creating the impression that the profession could not produce leaders. The most salient theme of the Indaba was to revitalise the profession, give it a new lease of life as it were.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

There is no doubt that the profession of social work to date has reached its lowest level in South Africa (Dlamini & Sewpaul, 2015; Sithole, 2010). The morale of social workers, mostly those employed by the state (Earle-Malleson, 2009; Loffel, Alsop, Atmore & Monson, 2007; Sithole, 2010; White Paper for Social Welfare, 1997) has reached an all-time low. Complaints regarding many issues are constantly voiced. These include poor salaries (Earle-Malleson, 2009) and thwarted upward mobility; insufficient stationery, vehicles and offices; malpractice; and ultimately burn-out. For the first time complaints do not revolve only around a too heavy caseload. Moreover, the unhappiness of professional social workers is reflected in their growing militancy, signified by recent protest marches staged at both provincial (in Limpopo) and national level. A protest march of social workers, the largest yet in South Africa's history, organised by Mokgadi Tjale, witnessed social work professionals demanding the tools of their trade and absorption into state departments of those granted bursaries by the DSD. Another issue of great concern to professional social workers is that, in the name of cadre deployment, persons who do not have training in social work are employed to supervise social workers (Dhlamini & Sewpaul, 2015), a situation analogous to a former good tennis player who is deployed to coach a soccer team, despite never having kicked a soccer ball.

Another problem which preoccupied social work practitioners was the professional rivalry which existed between themselves and child care workers regarding identity, terrain and scope. Following the South African Council of Social Services Professions (SACSSP) appointment of Professor Makofane, tasked with delineating the boundaries of the social services professions, this problem was partially resolved (Makofane, 2006). Currently child care workers are afforded their own unique SAQA-registered qualification and training institutions as well as programmes to attain their qualification.

Professional rivalry is not restricted only to child care workers. Rumblings and uneasiness between social workers and community development officers over turf suggest that the fight, in this case for a bigger slice in the macro environment, is far from over. This is the community development conundrum that is referred to. Social workers in the DSD are forced to make a crude choice between either continuing to work as social workers to the exclusion of community development, or practise community development to the exclusion of other social work methods. The Framework for Social Welfare Services (2013) envisages a lesser role (20%) for social workers in community development and a greater one (80%) in casework. For the author of this article and many in the profession, the choice that is forced down the throats of social workers is bizarre, in that it is impossible to contemplate social work to the exclusion of community work and community development. Besides this absurdity, the Framework for Social Welfare Services (2013) recognises the multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral nature of community development as an integral part of social welfare services and that all who have expertise in the area are free to practise. All this is happening against the training background in all South African universities, which historically and currently prepare students in the three primary social work methods, viz. casework, group work and community work, as well as the two secondary methods, viz. social case work and social work administration.

Since such pronouncements and subsequent legislation on either social work or community development, there has been a lot of dissatisfaction among social workers about this latest development. The dissatisfaction, in the author's opinion, stems from the fact that social workers are trained to practise community development and therefore the profession is kind of 'incomplete' without this essential method. Removing community development from social work practice is as good as emasculating the profession.

Needless to say, the debate has dragged on for too long and there are no easy answers. The question for the author was and is: Should universities continue to teach community development to undergraduate students when it is known that they would not be expected to practise it, at least in the DSD? Would this be prudent use of scarce resources? In a country where there are protests over service delivery every day, does it make economic sense to expend meagre resources on training students in something that they will never use? That is the community development conundrum to which the author referred in the title.

The training of social workers in South Africa covers two essential components, namely classroom-based lectures and practicum. For practicum purposes, students engage in community needs assessments where they profile communities, establish committees, conscientise communities about their problems and motivate them to act against those obstacles in the communities (Framework for Social Welfare Services, 2013). Yet when they exit universities, they are barred from practising this very task to which they have dedicated so much time, energy and money. How ethical is this? How sustainable is this for going forward? Is it therefore necessary to teach this part? Is it ethical to teach knowledge that students would not use? Is it worth spending scarce resources on this? Should universities continue teaching this aspect of the work?

REASON WHY OTHER PROFESSIONAL GROUPINGS WERE BROUGHT IN THE FOLD

Understanding the rationale for the inclusion of other professions in the social service fraternity has to be derived from the White Paper for Social Welfare (1997). The White Paper for Social Welfare (1997), the blueprint and vade mecum of social welfare services in South Africa, acknowledges the disparities of the social services delivery system during apartheid and identified the following goals in ameliorating the situation.

-

Restructuring and rationalisation of the social welfare delivery system towards a holistic approach, which would include social development, social functioning, social care, social welfare services and social security programmes.

-

There is an over-reliance on professional social workers and there is a need to expand human resources capacity through the employment of other categories of social service personnel, such as child and youth care workers, community development workers (my emphasis), social development workers and volunteers.

The latter strategic goal implies that social workers would not be the exclusive and sole providers of social services. It implies that another cadre of professionals needs to be trained and employed in this huge area of social services which was, of course, deliberately and strategically neglected by the apartheid government to advance the disempowerment of the majority of citizens by focusing exclusively on casework. Flowing from this, two (professional) categories of occupational groups were identified, namely child care workers and community development practitioners, who were tasked to ease the social workers burden, as it were. Unfortunately, some social workers do not see it as an easing of their burden but, justifiably or otherwise, as an erosion of their profession.

My brief, however, is to address the issue of community development, since child and youth care workers are on their way to being professionalised. For example, youth and child care workers are represented in the South African Council for Social Services Profession, have their own board and are probably paying their annual registration fees to the Council (http://www.sacssp.co.za). Therefore, the issue of child care workers is fait accompli.

Community development is also in the process of professionalisation (Hart, 2012). The White Paper for Social Welfare (1997) envisages the following for community development.

-

Community development strategies will address basic material, physical and psycho-social needs. The community development approach, philosophy, process, methods and skills will be used in strategies at local level to meet community needs. The community development approach will also inform the reorientation of social welfare programmes towards comprehensive, integrated (my emphasis) and developmental strategies.

-

Community development is multi-sectoral and multidisciplinary. It is an integral part of developmental social welfare. The focus of community development programmes in the welfare field will be on the following:

- The facilitation of the community development process;

- The development of family-centred and community-based programmes;

- The facilitation of capacity building and economic empowerment programmes;

- The promotion of developmental social relief and disaster relief programmes;

- The facilitation of food aid programmes in emergency situations as a result of disasters such as floods, fire, civil unrest or drought, or to alleviate acute hunger. Food aid of this nature will be a temporary measure until individuals and households can be incorporated into other social development programmes;

- Voluntary participation in social and community programmes will be actively encouraged and facilitated;

- Self-help groups and mutual aid support programmes will be facilitated where needed;

- Advocacy programmes will be promoted;

- The government will facilitate institutional development with the focus on creating and/or strengthening existing government institutions and organisations of civil society;

- Appropriate public education and non-formal education programmes will be facilitated;

- The promotion of community dispute resolution and mediation programmes will be embarked upon where needed. Training programmes will be provided;

- The access of local communities to governmental and non-governmental resources to address needs will be facilitated;

- Inter-sectoral collaboration will be promoted, while the separate functions of different sectors and government departments will be acknowledged.

Invariably, the areas listed above are areas that social workers claim as their own and the concept of welfare as used above did not help to make the situation any better. Hence there is still some clinging onto community development, even when the state says "leave it, for there is a dedicated group of people who will attend to it". In the midst of this dust and smoke, our vision is obscured. The key term in what the White Paper for Social Welfare (1997) envisaged is the whole notion of integration of services, meaning that each profession or occupational group must clearly delineate its niche area in the entire social service value chain.

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CHILDREN'S ACT (No. 38 of 2005)

The Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005) is a replacement of the Child Care Act (No. 74 of 1983), which focused largely on the parents rather than the children. Undoubtedly, the implementation of the Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005) was a step in the right direction in that it places more integrated responsibility among the social service professionals than ever before (Loffel et al., 2007). The Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005), as amended by the Children's Amendment Bill [B19F- 2006], requires a range of social service practitioners to deliver social services to children in the areas of partial care, early childhood development, prevention and early intervention, protection, foster care, adoption and child and youth care centres. Needless to say, these services are labour intensive, and effective delivery is dependent on the availability of skilled practitioners in the relevant disciplines and niche areas in the social services value chain. This includes social workers, child and youth care workers and early childhood development practitioners. However, there is a critical shortage of personnel in all of these categories, and if this is not addressed as a priority, effective implementation of the Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005) will be severely constrained.

In 2006 Barberton did a costing of the Children's Act Bill and concluded that in 2005 alone there were 11,372 registered social workers in South Africa. Less than half (5,063) of these were employed by the DSD or NPOs to deliver social services to vulnerable groups, including children. The costing revealed that at the lowest level of implementation of the (then) Children's Bill, at least 16,504 social workers would be needed in 2010/11 for children's social services alone (see also Earle-Malleson 2009; Loffel et al., 2007; Mbeki, 2007). Looking at the higher level of implementation, Loffel et al. (2007) eventually made the following statement: "There are clearly not nearly enough social workers in South Africa to deal with the huge demands for services caused by widespread social problems". This statement clearly implies that social workers cannot address the backlog of South African social services single-handedly, and that other professional groups such as community developers have to be brought on board.

In the light of these concrete facts and figures, it really perturbs the author that social workers want to cling to community development even when the government of the day advises and legislates to the contrary. Perhaps this is a question of passion and resistance (Van Nistelrooij & De Caluwe, 2016) or how people deal with issues of loss (Kübler Ross, 1969). Only further research in this area will unravel this mystery.

The White Paper for Social Welfare (1997) also made the several other salient observations. Firstly, the work required was too much for social workers and the human resource capacity was insufficient for addressing the country's social development needs. Secondly, not all social problems required intervention by social workers.

The most mind-boggling fact about social workers is their continuous litany of woe about heavy caseloads and inadequate resources. Yet when the DSD wants to relieve them of some of these burdens, they resist with a lot of energy. A lay preacher once related a story of an old woman who carried a portmanteau on her head in a fast-moving bus instead of placing it in the space reserved for such items. Nistelrooij and De Caluwe (2016) expressed it thus: "Confronted with paradoxes simultaneously is, as we see, like driving in a car punching the gas and hitting the brakes at the same time, and as a consequence spinning around in a circle, producing a lot of noise and smoke, while you don't get an inch forward". Are we any different?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Whereas the paper addresses itself to the community development conundrum in the 2000s, the thrust of the argument is what militates against social workers abandoning community development. The author's humble opinion is, rightly or wrongly, that social workers are resisting change that is meant to "benefit" them. In short, this kind of behaviour has all the elements of resistance, particularly since the directive emanates from the DSD, which has the national mandate to chart social development services in this country.

Van Nistelrooij and De Caluwe (2016) acknowledge that resistance to change was, until just a decade ago, presented in terms of Newtonian physics with a clear linear causal pattern in which every action is accompanied by an equal force in the opposite direction. Currently, change is seen as a very complex process accompanied by strong positive and negative emotions (Cartwright, Habib & Morrow, 1951). Change is unpleasant and for some it is a threat to the status quo.

This paper will borrow from the insights of cybernetics to explore this issue. Looking from a holistic or cybernetic perspective means that we look specifically at how outcomes are fed back to the performing whole - which in this instance is a group of people (social workers), an echelon, an organisation or even a network of organisations (see Van Nistelrooij & De Caluwe, 2016).

The community development conundrum also has implications for curriculum change. Therefore, some tenets of William Pinar's (2003) curriculum change theory will be utilised to address matters which are related to the curriculum. Curriculum change theory is fundamentally concerned with:

-

values, historical analysis of a curriculum and policy decisions;

-

theorising about the curriculum of the future, reflecting a political and societal agreement about the what, why and how of education for the desired society of the future.

Dennis Carlson writes that curriculum change theory is an interdisciplinary study of educational experience. It is a distinctive field with a unique history, a complex present and uncertain future. It is a historical construct assembled out of cultural battles over power and knowledge. Curriculum is a complex conversation.

Noting that social workers have since the emergence of the profession embraced community development, so later asking or instructing them to abandon this forces them to suffer feelings of loss. To some extent, Kübler-Ross's theory will be employed to explain some of these reactions. Kübler-Ross (1969) identified five stages that individuals (and by extension groups) go through in their reaction to loss. The stages are denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

METHODOLOGY

An exploratory study with a qualitative bent was initiated. A case study design was followed. Whereas case studies are distinguished by the size of the bounded case, such as whether the case involves an individual, several individuals, a group, an entire programme or an activity, they may also be differentiated in terms of their intent, viz. the single instrumental case study, the collective or multiple case study, and the intrinsic case study (Creswell, 2006). In this instance, the researcher used a multiple case study in which one issue of concern was selected and the inquirer selects multiple case studies to illustrate the issue.

PARTICIPANTS

An available and convenient sample of nine (9) academics at the University of Limpopo took part in the study. The age range of academics was from 33 to 58 years. Of these, four were male and five were female.

Another available sample of nine (9) practitioners was constituted. These were social workers who belonged to a chat group focusing on social work issues. The key defining variable of this group was that they had practised as social workers for less than five years.

DATA COLLECTION

In both instances the data-collection method was focus group discussion and both groups addressed themselves separately to the question:

-

Should universities (departments of social work) continue to teach community development?

-

What are the implications of this?

Each group had one session in which to address this topic.

DATA ANALYSIS

Stake (1995) provides a template for conducting a case study.

-

First, the researcher/s determine/s whether a case study approach is appropriate to the research problem. A case study is a good approach when the inquirer has clearly identifiable cases with boundaries and seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of the cases or a comparison of several cases. This the researcher established by identifying two groups with clear boundaries, namely social workers and social work educators.

-

Next, researchers need to identify their case. The case was clearly delineated, namely resistance to abandoning community development as a practice method against the background of a loud cry from the DSD and community developers.

-

The data collection in case study research is typically extensive, drawing on multiple sources of information, such as observations, interviews, documents and audio-visual material. In this particular instance a focus group discussion method was used to collect data.

-

The type of analysis of these data can be a holistic analysis of the entire case or an embedded analysis of a specific aspect of the case (Yin, 2003). Through this analysis the researcher provides a rich description. After this description, the researcher may focus on analysis of themes. Because the researcher selected multiple cases, a within-case analysis followed by a cross-case analysis as well as assertions was done in this particular instance.

THE FINDINGS: ACADEMICS

The sample was made up of participants who had been in the profession for a considerable time. They were trained in all three basic methods of social work, namely casework, group work and community work, as well as the two secondary methods of social work research and social work administration. Besides, the sample was involved in community development in various ways and capacities as classroom instructors or lecturers, supervisors of students' practicum, researchers, and community members and consultants. It is therefore not an incongruity to find that the dominant finding was in favour of continuing to teach community development in spite of the tempest around this:

"We teach beyond the orbit of the current government", was one response.

Participants provided strong reasons for their advocacy of community development. The older generation in the sample alluded to the fact that they taught community development during the period of apartheid, even though the government of the time seriously discouraged this. As members of a university, the respondents acknowledged their firm and inflexible commitment to the value of autonomy and freedom of inquiry (Bentley, Habib & Morrow 2006). Having said this, the group said they would continue to teach community development because it is the right thing to do. As for governments, they come and go but the truth remains.

Another participant expressed her consternation at the question asked:

"Circumstances may change, and then?"

The participants in the group expressed a strong sentiment that no government is permanent, and academics must remain steadfast and not allow themselves to be carried away. Community development is an integral part of social work (community work), and they will continue to offer this knowledge to students.

"Social workers may be forced to practise community development again."

Participants alluded to the fact that politicians are as changeable and as unreliable as weathercocks. Pretty soon, academics and training institutions may be exhorted to train social workers in this very area that they are discouraging now.

"We do not only teach for the South African market; other social workers practise overseas."

In justifying their unbending commitment to teaching community development, participants also reminded the researcher of the University of Limpopo's motto which is Finding Solutions for Africa. The researcher's attention was further drawn to the fact that the Department of Social Work has a considerable number of international students, who come from areas and countries that need more on community development than just casework. Limiting and indeed diluting the strength of the training programme in this regard would be immoral and a great disservice to the entire continent and its citizens.

Besides, most graduates from the Department of Social Work are not confined to South Africa after completing their studies. The Department prides itself on a considerable contingent of social workers employed in Canada, Britain and Ireland. To that end, the social work programme responds and appeals to an international market rather than to a parochial political whim.

"We do not only teach for DSD; social workers are employed by NGOs, world organisations such as WHO, UNESCO."

Members of staff also alluded to the fact that they do not train students for the DSD only and that most of their graduate students end up in the corporate and non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector, while others serve as private practitioners. In that sense, the social work programme has to be generic enough to cover all the needs and interests of the student population.

"We do not train for public service only; other social workers venture into private practice and may need this body of knowledge."

Indeed the social work programme at the University of Limpopo is generic and has to respond to the various needs of the students. The Department is mindful of the fact that, though it trains social workers, some students exit the programme to pursue interests remote to social work. In that regard, community development will be retained against the whims and caprices of those in power.

"Social workers need this knowledge to use for themselves in uplifting communities and neighbourhoods where they live."

The majority view among participants was more focused on social justice and equity, given that a greater percentage of students in the programme are from historically disadvantaged communities and they need this community development knowledge, first for themselves and secondly as citizens who wish to make a meaningful contribution in their communities. This latter view would coincide with Gray's (2009) definition of community development as "a democratic, grassroots or bottom-up, humanistic, people-centred approach that emphasises the participation and involvement of local people in all aspects of development and their empowerment through, among other things, education, conscientisation, awareness raising, capacity building, community action and community organising". The same principle is consistent with Marshall's third element in his classic formulation of citizenship rights, which is the provision of sufficient means for all people to engage in full social participation (Manning, 2007).

The dominant and "hegemonic" view notwithstanding, the minority view in this sample is also worth noting:

"Teaching community development is a waste of students' time and money."

This view is informed by the 80% casework and 20% (sometimes 10%) allocation advocated by the Framework for Social Services (2013). The proponents of the above view argue that social work training institutions should rather focus on improving the 80% that is allocated to the profession instead of spreading themselves widely and thinly across the space. This group expressed the unethical nature of insisting on teaching too much content that would not be of use to students in their practice.

"Is it ethical to teach people a skill that they will not need?"

Invoking the question of ethics, this section of the sample regard it as daylight robbery to make students and government pay for what they do not need.

"You already have a Directorate for Community Development."

Establishment of the Directorate for Community Development was seen as a clear signal of government's intention not to countenance social workers' inclusion in this regard. The Department of Social Work's insistence on teaching community development is likened to a dying person at the stage of denial and isolation, according to Kübler-Ross (1969).

"You already have institution/s training for community development, therefore you are duplicating."

Colleagues indicated that there were training institutions already offering qualifications in this regard and that the Department of Social Work was merely duplicating what is presented elsewhere. Because other institutions are offering a fully-fledged qualification in this area, and the Department of Social Work is only providing a section of it. The Department's training in this area runs the risk of being unfavourably compared to other institutions. In terms of Kübler-Ross's analysis, the Department of Social Work at the University of Limpopo could be said to be at the bargaining stage, characterised by "first steps in beginning to accept the situation, albeit with attempts to postpone confronting it" (Drower, 1990).

The Findings: Practitioners

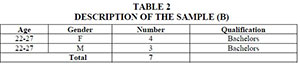

As can be seen from Table 2 above, this is a relatively young sample composed of social workers with only a few years' experience in the profession. One would expect that this group would not hold very strong views on the practice of community development, because their entrance into the profession coincided with the publication of the Framework for Social Welfare Services (2013). Here then follows verbatim accounts from this sample.

"Community development officers do not see a synergy between social work and community development; social workers do."

This sample's main concern is that the "new kid on the block", the community development officer, sees no connection between community development and social work. As such, the young social workers do not wish to impose themselves and their expertise on communities and community development officers/ workers.

As far as practitioners' views on teaching community development are concerned, this is what they had to say:

"There is no use in teaching community development."

"What is the point because we do not implement it?"

All practitioners in the sample alluded to the disingenuousness of teaching community development, since they do not practice this at work. Their question was why universities should spend precious resources on this aspect of training when they are not going to use it. In their opinion, universities are obsessed with community development and resist change.

This attitude is best captured in the following paragraph by Van Nistelrooij and De Caluwe (2016):

"A change process is not and cannot be merely a rational process. We, as human individuals, do not see ourselves as physical particles that follow nicely set-out trajectories when we are pushed to change or receive external impulses. Moreover, under these kinds of circumstances, we tend to do things more recursively and in cycles, moving along a lot but not seeming to function or operate in what is supposed to be the 'right' direction. The latter is the typical behaviour, which most of us associate with resistance as a result of planned change programs in combination with typical top-down change initiatives."

Other participants seemed to have resigned themselves to the reality that they would not practise community development and lamented as follows:

"All our programmes are divided, parcelled and given to smaller units."

"I am the master of all, yet I am neglected."

Kübler-Ross (1969) refers to this kind of emotional reaction as acceptance. Looking at it from another angle, the participants mourn the erosion of the profession as explicated by Dlamini and Sewpaul (2015). Social workers are of the strong conviction that the DSD has eroded their profession. Hence their slogan on the 19 September 2016 protest march was "Bring back our profession!"

DISCUSSION

Doubtlessly, community development is a conundrum in South Africa. Whereas the Framework for Social Welfare Services acknowledges the fact that the harvest is huge and the hands are few, there is a significant portion of the profession that feels that the DSD is eroding the social work professional base. This is one area where the views of both the seniors in the field and the young professionals converge.

The conundrum remains unresolved in that most social work educators insist that they would continue teaching community development regardless of what the government of the day may prescribe. On the other hand, newly qualified social workers find it an absolute waste of resources to teach something that would not be used in the future.

Age and occupation seem to be the separating constructs in this debate. Young qualified social workers do not see the reason for this, while the most senior social workers attached to training institutions advance solid reasons for the continuation of community development under the auspices of social work.

The Framework for Social Services suggests that all stakeholders must adhere to the guidelines contained in it, namely that 80% of the time should be devoted to casework and the remaining 20% to community development. It is interesting to note that there is no convergence of opinion on this. Academics did not pronounce on this formula, in all likelihood because the researcher did not probe this issue. This absence notwithstanding, the reality on the ground seems to be totally at odds with the prescripts of the Framework. Newly qualified social workers acknowledge the fact that they are not provided space to practise community development regardless of what the Framework says. This area needs further investigation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of the above exposition, the author recommends the following:

-

Establish whether social workers in the NPO/NGO sector still practise community development;

-

Survey all social workers on the need for training social workers in community development when in all likelihood they will not have the opportunity of putting this training into practice and, moreover, the government of the day also strongly discourages social workers from practising community development;

-

Investigate the extent to which the guidelines from the Framework are adhered to;

-

Conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine the opportunity cost of training social workers in an area that they will never practise.

REFERENCES

BENTLEY, K., HABIB, A., & MORROW, S. 2006. Academic Freedom, Institutional Autonomy and the Corporatised University in Contemporary South Africa. Research Report. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

CARTWRIGHT, D. 1951. Achieving change in people: Some applications of group dynamics theory, Human Relations, 4:388-392. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2006. Case Study Research. In: CRESWELL, J.W. (ed), Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches 2nd (ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. Framework for Social Welfare Services. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. Policy for Social Service Practitioners. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF WELFARE. 1997. The White Paper for Social Welfare. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DLAMINI, T.T & SEWPAUL, V. 2015. Rhetoric versus reality in social work practice: Political, neo-liberal and new managerialism influences. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 50(4):467-483. [ Links ]

DROWER, S. 1990. Health Care Social Work Practice. In: MCKENDRICK, B.W (ed). Social Work in Action. Pretoria. Haum Tertiary. [ Links ]

EARLE-MALLESON, N. 2009. In: ERASMUS, J. & MIGNONNE, B. (eds). Social workers in skills shortages in South Africa: case studies of key professions. Pretoria: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

GRAY, M. 2009. Introduction to Social Work. In: GRAY, M & WEBB, S (eds), Social work: theories and methods. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HART, C.S. 2012. Professionalization of community development in South Africa: process, issues and achievements. Africanus, 42(2):55-56 ISSN: 0304-615X:55-66. [ Links ]

KÜBLER-ROSS, E. 1969. On death and dying. London: Tavistock Publications. [ Links ]

LOFFEL, J., ALLSOP, M., ATMORE, E. & MONSON, J. 2007. Human Resources needed to give effect to children's right to social services. South African Child Gauge 2007/2008. [ Links ]

MAKOFANE, M.D.M. 2006. Demarcation of social services: professionalization and specialization. Pretoria: South African Council for Social Service Professions [ Links ]

MANNING, N. 2007. The politics of welfare. In: BALDOCK, J., MANNING, N. & VICKERSTAFF, S. (eds), Social Policy (3rd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MBEKI, T. 2007. State of the Nation Address of the President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki. Joint Sitting of Parliament, 9 February 2007. [Online] Available: http://www.info.gov.za/speeches/2007/07020911001001.htm [Accessed: 04/06/2016]. [ Links ]

PINAR, W.F. 2003. What is curriculum theory? Boston: Routledge. [ Links ]

VAN NISTELROOIJ, A. & DE CALUWE, L. 2016. Why is that we know we have to/or Want to Change, but Find ourselves Moving Around in Circles? Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(2):153-167 [ Links ]

SITHOLE, S. 2010. Marginalization of social workers in South Africa. Some feminist reflections. The Social Work Practitioner Researcher, 22 (1):7-19. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL FOR SOCIAL SERVICES PROFESSIONS. 2016. [Online] Available: http://www.sacssp.co.za/ [Accessed: 04/06/2016]. [ Links ]

STAKE, R.E. 1995. The art of case study research. Sage Publications. [ Links ]