Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 n.2 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-568

ARTICLES

Homeless in observatory, Cape Town through the lens of Max-Neef's fundamental human needs taxonomy

Rinie SchenckI; Nicolette RomanII; Charlene ErasmusII; Derick BlaauwIII; Jill RyanIV

IDepartment Social Work University of the Western Cape. cschenck@uwc.ac.za

IIDepartment Social Work University of the Western Cape

IIISchool of Economics North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus

IVDoctoral student in Child and Family Studies, Department of Social Work, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The level of homelessness on the streets of South Africa is regarded as a slow-moving tragedy. The aim of this article is to explain the profile of the homeless in Observatory, Cape Town using Max-Neef's Fundamental Human Needs taxonomy. A concurrent mixed-methods research design was implemented including 48 homeless persons living on the streets in Observatory. The quantitative data were analysed with SPSS and the qualitative data with Creswell's guideline for thematic analysis. The results clearly show the complexity of the lives of the homeless and that assistance to move out of homelessness will require complex and holistic efforts.

Homelessness in Cape Town

Homelessness is waking up daily on an ice cold pavement

Spending sleepless nights if it rains till

Morning…

It is hoping for a piece job

Elusive piece job

It is queuing for soap

From charitable churches

And conversion to begging

When you know you can work…

(Mahlangu, 1994)

BACKGROUND

The suburb of Observatory, also affectionately known as "Obs", is one of the older suburbs of the City of Cape Town, home to multiple cultures, a student population from the University of Cape Town, a variety of churches, the Provincial Government Groote Schuur Hospital, the Government Psychiatric Hospital Valkenburg, and the home of the South African Astronomical Observatory built in 1897- hence the name of the suburb. It is one of the oldest areas of Cape Town. Unfortunately Observatory also has a high crime rate and many homeless people.

In the beginning of 2014 concerned community members of Observatory approached the authors of this article to conduct a research study to profile the homeless in Observatory. The aim of this article is therefore to describe the profile of the homeless in Observatory, Cape Town and to develop some understanding of the lives of the homeless.

Homeless people: an overview of the literature

The United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UNCHS) (2000) states that the homeless represent the most obvious and severe manifestation of the unfulfilled human right to adequate housing. The UNCHS further states that few, if any, countries have entirely eliminated homelessness, and in many nations this phenomenon is clearly increasing rather than declining, adding that further action is clearly required to eradicate homelessness (UNCHS, 2000). This suggests the complexity of the phenomenon of homelessness and that it is not merely a matter of a shortage of housing.

The UNCHS further estimates that there are between 100 million to one billion homeless people in the world. The 100 million are the absolutely homeless or those sleeping on the street, while one billion are living in shacks (Olufemi, 2010; Sanchez, 2010). In South Africa around three million people fit the description of being absolutely homeless, while eight million are shack dwellers. Olufemi (2010) further states that Cape Town estimates that it has 900 homeless people. The Cape Metro Council Street Field Worker Project (CASP) conducted an audit on the homeless in Cape Town and found that there are, in fact, more homeless adults in Cape Town than street children, although the street children tend to get more attention (Olufemi, 2010). This homelessness on the streets of South Africa is regarded as a slow-moving tragedy that arouses anxiety in government and civil society (Cross, Seager, Erasmus, Ward & O'Donovan, 2010). As urbanisation, migration and unemployment increase, larger numbers of the poor are running the risk of becoming homeless. Cross et al. (2010) are also of the opinion that South Africa is not well prepared for increasing homelessness. Research on the homeless and best practice models is limited and mostly deals with small-scale projects (Cross et al., 2010).

The search for literature on the homeless revealed three major themes, as indicted below.

Challenges regarding the concept of homelessness

Studies of homelessness, according to Sanchez (2010), are confronted with many conceptual and methodological challenges depending on the definitions used for the concept "homeless". The UNCHS classifies the homeless as people who are roofless, houseless, have insecure accommodation, and inferior or substandard housing. To complicate matters, Sanchez (2010) and Tipple and Speak (2005) further state that the individuals also have their own subjective idea of what homelessness is and where "home" might be.

There are those in the category of "absolute homelessness" - they sleep in the open - and then there are those who are "at risk" of becoming homeless. The 'absolutely homeless' people are seen as sleeping in the open one or more nights per week and/or making use of shelters for the homeless (Seager & Tamasane, 2010). Olufemi (2010) adds to the description of the homeless by indicating that they cannot meet basic needs or lack access to basic services such as water or sanitation, and cannot satisfy personal needs (Olufemi, 2010). For the purpose of this study the focus will be on "absolute homelessness", the "roofless" or those "sleeping rough" in Observatory, Cape Town.

Complexity of homelessness

The UNCHS (2000), Tipple and Speak (2005) and Cross et al. (2010) further point out that it is very difficult to research, address and eliminate homelessness because of the complexity of the reasons for becoming and being homeless. Reasons could include long-standing poverty, unemployment, difficult family life, little or no schooling, substance use/abuse, and health and mental health problems, which prevent them from moving out of poverty and off the streets (UNCHS 2000; Cross et al., 2010; Makiwane, Tsiliso & Schneider, 2010; Olufemi, 2010; Sanchez, 2010; Seager & Tamasane, 2010).

Tipple and Speak (2005) refer to the fact that the concept "home" embodies ideas such as comfort, belonging, identity and security. Homelessness then refers to coldness, indifference, stress, alienation and instability. Being homeless implies that the person is exposed to health problems, runs the risk of getting hurt, being exploited in a variety of ways, does not have access to basic facilities or proper food, and creates environmental health problems (Richter, Burns & Botha, 2012; Seager & Tamasane, 2010). Because of their homelessness people also become voiceless, powerless and live without dignity (Olufemi, 2010; Parker, 2012; Tipple & Speak, 2005).

Addressing homelessness requires multifaceted policies and responses

There is little research on best-practice models on sustainable, multifaceted policies and responses to homelessness, despite the guidelines given by the UNCHS (2000). Cross et al. (2010) mention that there are no clear policies or consensus on how to deal with the homeless in South Africa. The study by Sanchez (2010) found that it is mostly faith-based organisations in Johannesburg and Pretoria which render a variety of services to the homeless, including providing shelter, assistance in finding jobs, food, health care and counselling. Sanchez (2010) further indicates that these organisations have a good understanding of the complexity of being homeless and their services are regarded as very valuable; however, these organisations do not offer sustainable structural solutions which provide opportunities to exit conditions of poverty and homelessness (Richter et al., 2012). In order to address homelessness there should be a move towards multifaceted, multidisciplinary, long-term structural changes (Richter et al., 2012; Sanchez, 2010). The UNCHS (2000) confirms the complexity of addressing homelessness and proposes holistic, policy-driven processes.

Theoretical framework for the study

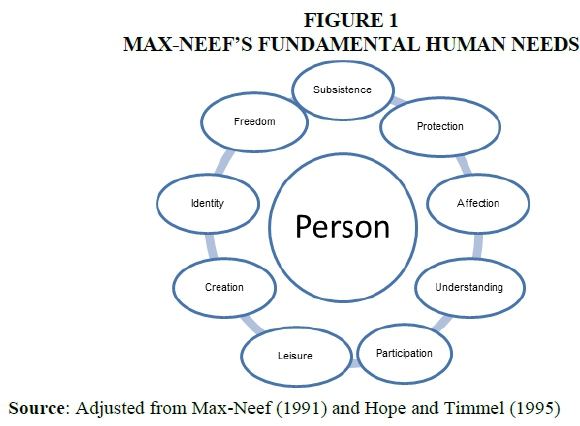

The theoretical framework used to make sense of the research data is Manfred Max-Neef's taxonomy of Fundamental Human Needs (FHNs). Max-Neef, a Chilean economist and environmentalist, identified nine FHNs that all people experience (Hope & Timmel, 1995; Max-Neef, 1991; Schenck, Nel & Louw, 2010). The nine FHNs are illustrated in Figure 1.

Max-Neef (1991) views these nine FHNs as infinite and part of the human being as a whole and, if one dimension of the FHNs is not met, the person is affected in total and experiences poverty in one or more of the dimensions. In contrast to Maslow's scheme, the needs are not seen as hierarchical (Grobler, Schenck & Mbedzi, 2013). Max-Neef's main contribution is the distinction he makes between needs and satisfiers. While needs are few (9), finite, classifiable and constant through all human cultures, one the one hand, satisfiers, on the other hand, are different, depending on the person in his/her context.

The implication of the theory, as confirmed by Tippel and Speak (2005), Max-Neef (1991) and Schenck et al. (2010), is that homelessness does not only create poverty of subsistence, but has implications for all other dimensions in the person's life. It is also the lack of other FHNs such as affection, participation, creation and understanding that may contribute to the vulnerability of persons and result in their becoming homeless, as will be described in the discussion of the results.

Methodology

A mixed methodological approach, including both qualitative and quantitative methods, was used in order to gather data on the homeless.

A concurrent mixed-method design was followed. Quantitative data were collected with the use of a questionnaire. The questionnaire had some qualitative questions, where we needed explanations or clarification. Qualitative data were collected, with an interview guideline, in the same interview after the questionnaire was completed. The focus of the qualitative data was to collect information linked to the reason for being homeless, their family life and life on the streets of Observatory.

Quantitative data were analysed with support from the SPSS version 22. Data analysis consisted of descriptive statistics. Qualitative data were analysed with thematic analysis (Creswell, 2007). The article presents both the quantitative and qualitative data.

Permission for the research was granted by the Senate Research and Ethics Committee at the University of the Western Cape. All the participants were provided with an informed consent form, which explained the aim and purpose of the study and their right to confidentiality and anonymity. All participation was voluntary and participants were free to leave at any stage during the research process. For the participants who could not read, the consent form was explained to them.

Ten fourth-year social work students from the University of the Western Cape were fieldworkers in this research. In total they interviewed 48 participants in Observatory. The fieldworkers were trained and prepared to complete the questionnaires and conduct the individual interviews.

Availability sampling was used as the population was not known. The criteria used for the selection of the homeless were that they should fall into the category of "absolute homelessness", meaning that they sleep in the open and/or make use of the shelters in Observatory, and they should be adults (over 18 years). The study did not include homeless street children.

The results of the concurrent mixed-method study are presented and described with both qualitative and quantitative data in support of each other and not as separate findings, increasing the trustworthiness of the data.

RESULTS

The demographic data are represented in Table 1. The participants consisted of 34 males and 14 females, and the population varied across gender, race, language and marital status.

The biographical data of the homeless

Table 1 shows that 70.8% of the homeless are males and 29.2% are females, while most (64.6%) are coloureds, followed by blacks (25%) and whites (8.3%). The fact that the study was done in the Cape Town area can explain why the majority of participants are from the coloured population as this is the majority population (50.2%) of the Western Cape (Stats SA, 2011). It was also interesting that one of the white participants made the following remark: "the coloureds think that only they can be homeless and whites are rich and we don't belong here".

Table 1 further shows that the majority of the homeless in Observatory are South African (98%), while only two per cent (2%) were from Zimbabwe. In the national study by Kok, Cross and Rowe (2010), 14% were foreign nationals while 86% were South African citizens. This coincides with the studies by Blaauw (2010) on day labourers and Viljoen (2014) on waste pickers in South Africa, where the foreign population amongst the day labourers and waste pickers was less than 10%. The results of the study by Kok et al. (2010) and Seager and Tamasane (2010) further support the results of this study, as only 12% females were counted among the homeless in South Africa, while the majority (88%) were males.

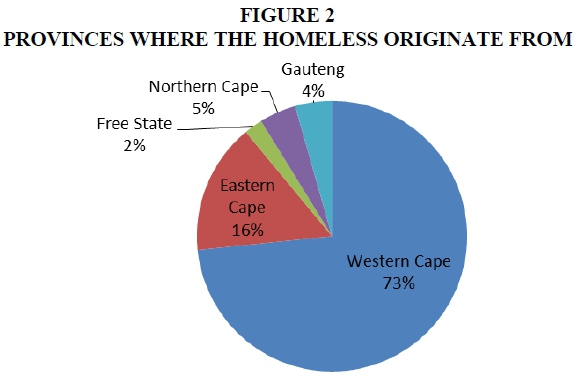

The figure below shows the provinces where the homeless origrate from.

The majority (73%) of the respondents were from the Western Cape, although not necessarily from Cape Town, while 26% of the homeless were from only four of the other provinces: the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Free State and as far as Gauteng, which is an indication of the degree of dislocation from their families. The main reason for being on the street was given as poverty. The participants migrated from rural areas or other provinces, and even other countries, to look for work in Cape Town. They end up on the street as they do not have any other place to stay, cannot afford to pay for a place to stay and "could not find work and end up on the street" and "I came to the Western Cape from the Eastern Cape to look for work".

The Zimbabwean participant came to look for work: "I do not have family or relatives (to stay with)." Another participant shared that he came to Cape Town to look for work but on arrival he suffered a stroke. He did not have sufficient money to return, cannot work and therefore lives on the street. The study by Harmse, Blaauw and Schenck (2009) shows clearly the migration of day labourers from the less resourced rural to the urban and more resourced areas. The UNCHS (2000) view migration as one of the major sources of homelessness.

Time spent on the street

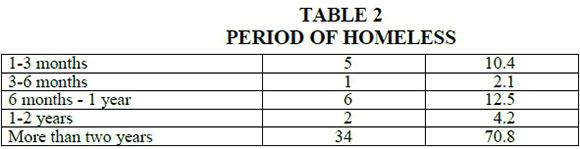

Kok et al. (2010) indicated that the average length of time the homeless spent on the streets was 6.4 years. Unfortunately the questionnaire used in this study only made provision to determine how many homeless spent between 0-2 years and more on the street. Seventy-one per cent (71%) indicated that they have been on the streets for more than two years. This was an oversight when the questionnaire was compiled. One of the participants indicated that he has been homeless for the last 15 years.

"Ek is nie bang om op die straat te slaap nie - ek kom nou al meer as 15 jaar op die pad." (I am not afraid of sleeping on the street - I have already been on the street for 15 years road.)

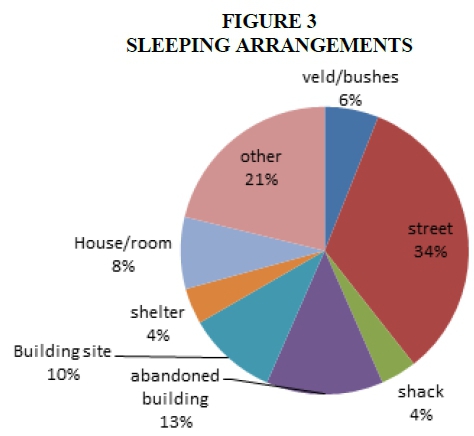

An elderly person also shared that "I have been homeless … since I was 16 years old". A criterion to be included in the study was that the participants should be in the category of "absolute" homelessness. The figure below indicates the sleeping arrangements of the homeless.

Figure 3 shows that the majority of the people sleep on the streets of Observatory and only 4% sleep in shelters, which therefore confirms that they are "absolutely" homeless, roofless and sleep rough. The results are supported by Kok et al. (2010) in the national study, where only 10% indicated that they sleep in shelters. In the study by Makiwane et al. (2010), a third (10 out of the 30 interviewed) of the people slept in shelters and the rest slept on the streets, in the veld, in abandoned buildings and under bridges. The 8% who indicated that they sleep in a flat/room/house can strictly speaking not be regarded as "absolutely" homeless. It might also be that they may have referred to a room in a shelter or abandoned buildings. It is not clear why so few make use of the shelters and this aspect needs further exploration. Our assumptions are that it may have to do with the costs involved and the fact that they cannot use substances when in the shelter, as one participant shared: "The worst thing is fighting and drinking until you pass out … we drink everything on the streets".

An aspect which needs to be further investigated might be that shelters, established and run by faith-based organisations, will not allow couples who are not married to be together, as stated by a female participant:

"Ek wil nie op die straat wees nie want ek kry nat op die straat … weekends moet jy buitekant sit en dan vry jy vir jou dik buite … Hulle accept nie couples nie soos without marriage nie." (I do not want to sleep on the street as it is cold and wet … weekends you have to sit outside and make love outside as they do not accept couples if you are not married.)

Food security

Sleeping on the street and not having a regular income results in food insecurity. The World Health Organisation (WHO, 2014) views food security as the condition when all people have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food at all times to maintain a healthy and active life.

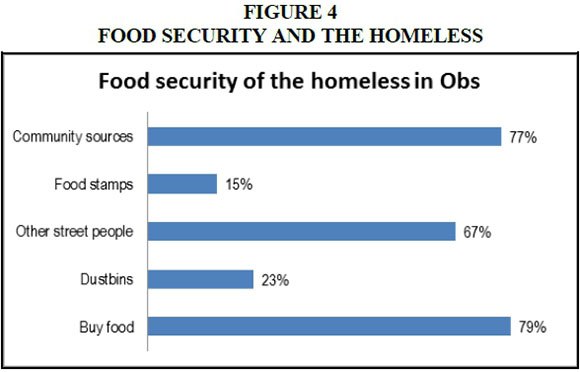

The question posed to the participants was to determine through which sources they access food. The participants could refer to more than one source, as indicated in Figure 4.

Although we could not establish directly whether the homeless can access food on a daily basis, we could deduce from the answers reflected in the above figures that they are food insecure, as 23% indicated that they look for food in dustbins on the street. Moreover, 67% indicated that they assist each other in obtaining food. At times and when they have money, they will buy food (79%). Seventy-seven per cent (77%) access food from soup/food kitchens in Observatory and the neighbouring areas. Whether they have food every day was not determined. Being food insecure, according to Wood (2010), is - like being homeless - a further form of social exclusion. Wood (2010) explains that food insecurity can result in undernourishment, which leads to other health and behavioural problems that in turn alienate the affected even more from society.

Educational level of the homeless

The UNCHS (2000:iv) report states: "There is little doubt that the best way to combat homelessness is to avoid people becoming homeless in the first place". Low educational qualifications and unemployment are some of the contributing factors to being vulnerable to becoming homeless (UNCHS, 2000). The educational level of the participants are presented in figure 5.

Figure 5 indicates that only 18.8% of the homeless passed Grade 12 and none had any post-matric qualifications. In total 33% had a primary school qualification, while 4% had no schooling at all. Forty-four per cent (44%) have some high school qualifications.

Makiwane et al. (2010) also mentioned lack of education as a reason for being unemployed and on the street. Similar findings were reported by Blaauw (2010) on day labourers in South Africa, Viljoen (2014) on the street waste pickers and Schenck et al. (2012) on the landfill waste pickers in the Free State. Blaauw (2010) indicated that 15% of the day labourers in South Africa had passed Grade 12, while nine per cent (9%) of the street waste pickers had passed Grade 12 and only five per cent (5%) of the landfill waste pickers in the Free State had passed Grade 12 (Schenck et al., 2012) and therefore had to make a living in the informal sector. In this study and all the other studies mentioned (Blaauw, 2010; Schenck et al., 2012; Viljoen, 2014), poverty in the families of origin, who were thus not able to support the person through school, were given as one of the main reasons for not completing school.

Sources of income

Kok et al. (2010) found that 27% of the street people indicated that they do some form of work, although they mentioned that they did not investigate what type of work the street people were doing. Work may have meant activities in the informal sector, such as guarding cars, pushing trolleys, waste picking and day labour work, as was found by Makiwane et al. (2010). In this study the question was asked as to what their sources of income were. The participants could indicate more than one source of income, as indicated in Figure 6.

The sources of income were indicated as day labour (65%), waste picking (30%), street trading (2%), government grants (22%) and support from relatives (2%). Begging was mentioned by 19% of the homeless as a source of income. None of the homeless mentioned formal work as a source of income. The CASP study in Cape Town also confirms that some of the homeless people are involved in day labour or other piece jobs (Olufemi, 2010). One of the participants stated that he "krap in die dromme, skarrel die beste vir my, kyk, ek werkie." (scratch in the rubbish bins as I do not work.")

Kok et al. (2010) and Seager and Tamasane (2010) further highlight the plight of the homeless as having difficulty in accessing grants because of their appearance, low educational qualifications and lack of identity documents. Kok et al. (2010) further mention that those at shelters have a better chance of being assisted with grants as the shelters usually provide support and access to state departments.

In the qualitative interviews some participants shared that, being unemployed, they were forced to leave home in search of work and could not return if they were not able to find work "as jy nie werk nie dan … is jy vervloek" (if you do not work ... you are cursed). Another participant mentioned that he was "evicted by his wife" because he did not have work. A further participant shared that his mother chased him out of the house: "I am a male in the house and it is my duty to provide and support my family. I did not have a job and my mother expected from me to bring in money for the family. Eventually my mother chased me away … I did not manage to find a job and became homeless." In support of the comments by the participants, the UNCHS (2000) view unemployment as one of the major contributing factors to homelessness, in particular for males. Men, according to the UNCHS (2000), are usually made homeless by material difficulties, while women more often become homeless as a result of abusive relationships and evictions, as will be illustrated in the next section. The UNCHS (2000) also states that homelessness occurs when core social relations have changed so that traditional households cannot function adequately. Linked to this notion Viljoen (2014) and Schenck and Blaauw (2011) noted that many street waste pickers are sleeping on the street as they cannot leave their trolleys unattended, and Blaauw (2010) found that day labourers often sleep on the street for reasons such as not having enough money to go home every day, or that they are migrants with no home in the city in which they do day labour.

Mental health, health and behavioural problems

The UNCHS (2000) explains that it is well known that the health, mental health and behavioural problems of the homeless can be seen as a contributing factor to their homelessness and it is this aspect, according to Makiwane et al. (2010), which makes it so difficult to find a road out of homelessness.

One of the participants explained that he "was in Valkenburg (psychiatric) Hospital" and could not return to his family or access work. Another said: "I got injured and I could not work. I felt useless at home so I decided that I needed to do something for myself" and was now looking after himself on the street.

The participants further stated that their own behaviour is one of the reasons for their homelessness, which is linked to their alcohol and drug abuse, bad friends and criminal behaviour, which brought them into conflict with their families.

"…have bad friends, stealing, fighting and using drugs, in my case I am using heroin … the worst part is I do not stop using it."

"…my family is good and I am bad that is why I moved out … my sister achieved and I gave birth to a disabled child…." (crying)

"I am a drinker and my family cannot cope with me so I decided to come to the streets to drink whatever I get. I want to be on my own … I took the decision myself so that I cannot stress other people."

"Ended up in prison and I do not want to return home - choose to remain on the street."

Substance abuse is seen by the UNCHS (2000) as both cause and condition of homelessness, while Makiwane et al. (2010) in particular emphasise the link between homelessness and the behavioural and relational problems of the homeless. Herman, Susser, Struening and Link (1997) further mention that studies on homelessness have found a remarkably high prevalence of adverse experiences during childhood, primarily histories of out-of-home care (foster, group or institutional care) and running away from home. Makiwane et al. (2010) confirmed such findings; 16 interviewees in their study reported having had a poorly functioning family structure during childhood and behavioural problems as a result. The fact that these adult interviewees mentioned these issues suggests that they believe it had some bearing on their eventual homelessness. This will be further explained in the next section.

Family functioning

Table 3 shows that only 17% of the homeless are married and 12.5% were with a partner on the street. The rest have never been married (56%), are separated/divorced (4%) or widowed (8%). Similar to these findings, Kok et al. (2010) found that in South Africa 70% of the homeless have never been married and 12% were married. This might be an indication of their "dislocation" from family life, family problems and difficult relationships, as was expressed in some of the previous comments. The participants described a variety of family problems which acted as push factors for leaving home and living on the streets.

Overcrowding

Overcrowding was described by some participants as a push factor to leave home:

"… hulle bly in een vertrek in … wendy huis en nou daai maak dat daar nie plek is vir my nie … my freedom kan ek nie kry by hulle nie." (they live in a wendy house (wooden backyard shack) and there is no space for me - I did not have any freedom.)

"I decided to run away from home and live on the street. I feel more comfortable in the fresh air, because the house became too crowded."

Abusive relationships

The participants said that abusive relationships made them leave home. This was mentioned mostly by the females on the streets. It is significant to note that it seems as if these female participants did not have alternative support systems or safety nets other than going to the street, which increased their vulnerability.

"Family is there to protect us … but my family destroyed me. That is why I do not have a family … She (mother) did not protect me, she abused me and did whatever she wants."

Two females stated respectively that they were "sexually abused by mother, father and grandfather" and ran away; "my mother, my mother's dad, my grandfather (all) abused me and raped me".

Another stated:

"My husband used drugs and drank a lot. He always hit and abused me and I get used to sleep on the street."

"ek was in 'n abusive relationship" (I was in an abusive relationship.)

It was further highlighted that drugs and alcohol also played a major role in these abusive relationships, which was confirmed by Parker (2012) and the UNCHS (2000), which described the abusive relationships in which the females were involved.

Dislocated/rejected relationships

To emphasise the troubled relationships of the homeless even further, the participants described more incidences of troubled family relationships as reasons for being on the streets.

A male participant explained that his "sister sold the house and I had nowhere to stay". One of the younger homeless women's mother "chased her out of the house", while another female participant said: "My mom moved to London ... well, my dad used to live here and I wanted to live with him so my mom bought me a bus ticket to come live with him … he (father) then passed away and I ended up here."

One woman said that her "mother married her boyfriend and I could not handle it" and she left home. Another woman shared that her cousin chased her out of the house "after I had slept with her (cousin's) husband."

Further references were made to "sibling rivalry" and "bad relationships" and deceased families, leaving them as orphans: "My parents passed away and I had to look after myself from an early age."

Some of the participants expressed their sadness at being away from their families:

"Dis baie belangrik om 'n familie te het. Ek wens ek het nog 'n familie … 'n huis … vrou … kinners … 'n man by sy familie. En nou slaap ek buite mos oppie pad." (It is important to have a family. I wish I still had a family, a house, a wife and children. Now I am sleeping on the street.)

One participant does not know his mother at all as she left him when he was a baby. He expressed the wish to meet his mother: "Ek wil so graag my ma sien maar ek kan nie." (I really want to see my mother but I cannot.) Apparently she rejected him as a child:

"Ek weet nie, ek weet nie wat is moederliefde nie … ek voel nie om nog daaroor te praat nie." (I do not know what motherly love is. I do not feel like talking about it anymore.)

"ek huil nie meer vir hulle as my familie nie." (I do not cry for my family anymore.)

"Soos ek sê hulle (familie) kontak my nie. Dis nie iets om oor tevrede te wees nie." (The family does not contact me. It is not something to be satisfied about.)

Makiwane et al. (2010), Smith (2008) and Smith (2010) also observed that most of the homeless are on their own and their findings supported their theory that adverse childhood experiences, dysfunctional families and domestic problems are contributing factors to homelessness.

Since they no longer had a family or were not living with their families, it emerged in the interviews that some of the homeless created new, supportive relationships amongst each other.

Creating supporting relationships and new "families"

Table 4 shows that 69% of the homeless indicate that they support each other in a variety of ways, such as accessing food (65%), protecting each other (46%), providing or sharing shelter (42%) and providing care when sick (42%). Similar support was expressed by the day labourers in the study by Blaauw (2010), and of the street waste pickers by Viljoen (2014) and in the US studies by Smith (2008) and Smith (2010).

One of the themes from the research was the "family" bond some of the homeless on the street created with their co-street members. A participant referred to his "pad familie" or "street family". Makiwane et al. (2010) also refer to the "family units" created among the homeless that they interviewed in Pretoria and Rustenburg, which "filled the vacuum" left by their own families (Makiwane et al., 2010:44). Some of the narratives shared were the following:

"My boyfriend is very supportive and caring … he can bring food for us and care for us. If I am sometimes sick he gave me money and takes care of me."

Another woman shared that the boyfriend she has on the street "do not use drugs, like the way my husband used to … This one is caring". Another confirms "My family is the homeless people who are caring and taking care, even if I am in hospital they are there for me (he has TB)."

"all people on the street are my family … my sister, this means we share good and bad stories together."

"Ek het kom leer buitekant wat dit is om regtig familie te he. Dit is mense wat toenadering soek, liefde, en dit het ek kom leer buite op die straat … dit is wat jy noem jou familie. Jy kan nie staatmaak op jou eie familie nie maar jy kan staatmaak op die groupie wat saam met jou is wat jy kan hulle noem jou familie." (I learned on the outside what it is to have a real family. These are people who want a close relationship, love, and this I learned on the streets ... this is wat you can call your family. You cannot rely on your own family but you can rely on this little group with you that you can call your family.)

"Ek het chommies ja … maar nie familie nie. Ja ons is family op die pad. Ons bly saam … ons maak vuur, ons maak kos saam … ons slaap, in die oggende staan ons op dan drink ons 'n biertjie of twee." (Yes, I do have pals ... but no family. Yes, we are family on the street. We live together ... we make a fire, we cook together ... we sleep, in the mornings we get up and and have a beer or two.)

"Dai is nou my family. Dai is nou my pad familie." (This is actually my family. This is now my street family.)

"Hulle gie om vir my, ek gie om vir hulle…" (They look after me, I look after them.)

Another participant also elaborated on how they have to manage relationships and group dynamics similar to they way families do:

"ons leer ma elke dag om mekaar te leer ken en hoe om mekaar te respek en om jou mond te hou as jy nie 'n regte antwoord het vir hulle nie." (We learn to get to know each other every day and how to respect each other and to keep your mouth shut if you do not have the right answer.)

One of the participants described a different form of group that he views as his family:

"Ek het baie lang tyd in die tronk spandeer … die mense saam wie ek in die tronk gelewe het - dai is my familie … The prison family have respect and discipline - not the people on the street … Dit maak dat ek my soma net een kant hou van hulle (homeless) af…" (I spent a long time in jail ... the people with whom I lived in jail - they were my family ... The prison family have respect and discipline - not the people on the street … the result is I keep myself apart from the street people.)

In summary it seems that most of the people on the street are experiencing care and support from their "street families", as mentioned in the following two comments:

"To be honest, to be really honest I take them (other street people) as my family because why they don't even hurt me, they do nothing wrong with me. They care for me."

"They give me love that I did not get from my mommy and they do not abuse me … They are always there when I need them most."

Diener and Seligman (2002), Hartling (2008), Smith (2008), Smith (2010) and Doll, Jones, Osborn, Dooley and Turner (2011) found that the supportive relationships are major contributors to the resilience of people and were important for the subjective wellbeing of the homeless.

Sense of independence and without responsibility

The homeless participants expressed a strong sense of independence as a pull factor to be on the street:

"As ek alleen is ... dan is ek die gelukkigste mens." (If I am alone … Then I am the happiest human being.)

"With having no house, I do not have to worry about paying bills, or worry about any house problems."

"The nice thing is to be on your own and to do as you please without stressing other family members."

"... dat ek net na myself kan kyk. Ek het nie nog mense wat my ongelukig maak nie. So my lewe op straat is maar net elke dag gelukkig. Ek probeer net om myself gelukkig te hou." (... so that I can look after myself. There are no people who can make me unhappy. So my life on the street is happy every day. I try to keep myself happy.)

"ek doen ma net 'n honest man vir myself is al." (I am just living and honest life for myself.)

Hamilton, Paza and Washington (2011) confirm the sense of independence among the homeless, but this independence also refers to not having responsibilities, as confirmed by Crane, Warner and Coward (2012) in their study in which they attempted to assist 400 homeless people in the UK to live "independently", which included taking on responsibilities and creating vast support networks, which will be elaborated on in the discussion.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The aim of the article was to profile the homeless on the streets of Observatory through the lens of Max-Neef's taxonomy of Fundamental Human Needs. The results showed that the lives of the homeless are as complex as described in other studies such as Makiwane et al. (2010), Kok et al. (2010), Parker (2012), Crane et al. (2012) and the UNCHS (2000). The question is therefore: "How can these results assist us in dealing with the homeless?"

One of the participants summarised their position:

"Ek het nêrens om na te draai nie. Ek wietie wat lê by die einde van die tonnel nie." (I have nowhere to go. I do not know what is at the end of the tunnel.)

Makiwane et al. (2010) stated that many of the homeless have lost all hope of getting back into mainstream society and are thankful for any welfare and helping hand that comes their way. This statement was confirmed when the participants were asked what assistance they would welcome. Eighty-one (81%) indicated they would welcome clothes, access to water and toilets (67%), food (62%), employment (67%) and medical assistance (52%), as well as assistance in applying for an ID (56%).

They explained further that since Cape Town's winter is the rainy season, this is the worst part of their existence:

"for a homeless person you look for just a shelter for before the winter, the winter is coming … you know how cold it gonna be this winter."

"when it is raining you have to walk up and down. You wet, you smell, you hungry, you have to go and sleep with a wet blanket."

Assistance only on a subsistence level, as stated by the participants, will help the homeless merely to survive on the streets and will not facilitate their exiting homelessness (Crane et al., 2012), as the homeless are experiencing poverty in all the dimensions of Max-Neef's Fundamental Human Needs. As can be seen from the results of the study, being homeless does not mean that a person is only roofless and sleeping rough, but all dimensions of the homeless person's existence are affected and this contributes towards and maintains the homeless condition of the person. This is summarised in Table 5.

The study by Crane et al. (2012) shows clearly the difficulty of attempting to assist the homeless towards independent living off the street. The homeless gained satisfiers such as more dignified living conditions, but the "satisfier" brought loneliness away from their unconditionally accepting street family. Having "independent living conditions" in the form of a house or an apartment brought responsibilities such as management of bills and avoiding substance abuse. It took the intensive support of a team of professionals over a period of at least three years to assist the participants into "independent" living.

In summary, to address the issue of homelessness the comment by one of the participants might provide the best guideline:

"ek is net soe important soes jy. Jy kenni my challenge wat ek hettie." (I am as important as you are. You do not know the challenges I face.)

It took a complex series of events to lead to homelessness. Applying the Max-Neef taxonomy implies holistic and complex support efforts and a participatory journey with the homeless into a way of living which is acceptable for them and the rest of society.

REFERENCES

BLAAUW, P.F. 2010. The socio economic aspects of day labouring in South Africa. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

CRANE, M., WARNER, A.M. & COWARD, S. 2012. Preparing the homeless for independent living and its influence on resettlement outcomes. [Online] Available: http://www.feantsaresearch.org/IMG/pdf/ejh6_2_article1.pdf. [Accessed: 10/01/2015]. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

CROSS, C., SEAGER, J., ERASMUS, J., WARD, C. & O'DONOVAN, M. 2010. Skeletons of the feast: a review of street homelessness in South Africa and other world regions. Development Southern Africa, 27(1):5-20. [ Links ]

DIENER, E. & SELIGMAN, M.E.P. 2001. Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13:80-83. [ Links ]

DOLL, B., JONES. K., OSBORN, A., DOOLEY, K. & TURNER, A. 2011. The promise and the caution of resilience models for schools. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7):652-659. [ Links ]

GROBLER, H., SCHENCK, R. & MBEDZI, P. 2013. Person centred facilitation: process theory and practice. Cape Town: Oxford Press. [ Links ]

HAMILTON, A.B., PAZA, I. & WASHINGTON, D.L. 2011. "Homelessness and trauma goes hand in hand": pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Women's Health Issues, Jul-Aug 21. [Online] Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21724142. [Accessed: 25/10/2014]. [ Links ]

HARMSE, A., BLAAUW, P. & SCHENCK, R. 2009. Day labour, unemployment and socio economic development in South Africa. Urban Forum, 20:363-377. [ Links ]

HARTLING, L.M. 2008. Strengthening resilience in a risky world: it's all about relationships. Women and Therapy, 31(2-4):51-70. [ Links ]

HERMAN, D.B., SUSSER, E.S., STRUENING, E.L. & LINK, B.L. 1997. Adverse childhood experiences: are they risk factors for adult homelessness? American Journal of Public Health, 87(2):249-255. [ Links ]

HOPE, A. & TIMMEL, S. 1995. Training for transformation: a handbook for community workers. Gweru: Mambo press. [ Links ]

HSRC REVIEW. 2010. Skeletons at the feast: a review of street homelessness in South Africa and other world regions. Pretoria: HSRC. [ Links ]

KOK, P., CROSS, C. & ROWE, N. 2010. Towards a demographic profile of the street homeless in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 27(1):21-37. [ Links ]

MAHLANGU, J. 1994. Homelessness. Homeless Talk, 7. [ Links ]

MAKIWANE, M., TSILISO, T. & SCHNEIDER, M. 2010. Homeless individuals, families and communities: The societal origins of homelessness. Development Southern Africa, 27(1):39-49. [ Links ]

MAX-NEEF, M. 1991. Human scale development: conception, application and further reflection. New York: The Apex Press. [ Links ]

OLUFEMI, O. 2010. Feminisation of poverty among the street homeless women in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 17(2):221-234. [ Links ]

PARKER, J.L. 2012. Self-concept of the homeless people in an urban setting. Process and consequences of the stigmatised identity. [Online] Available: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1064&context=sociology_diss. [Accessed: 15/11/2014]. [ Links ]

RICHTER, S.M., BURNS, K.K. & BOTHA, A.D.H. 2012. Research planning for global poverty and homelessness policy and services: a case study of a joint Canadian-South African initiative. Journal of Social Science Research, 1(3):85-91. [ Links ]

SANCHEZ, D. 2010. Civil society responses to homelessness. Development Southern Africa, 27(1):101-110. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, R. & BLAAUW, D. 2011. The work and lives of street waste pickers in Pretoria - a case study of recycling in South Africa's urban informal economy. Urban Forum, 22:411-430. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, R., NEL, H. & LOUW, H. 2010. Introduction to participatory community practice. Pretoria: Unisa. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, C., BLAAUW, D. & VILJOEN, K. 2012. Unrecognized waste management experts: challenges and opportunities for small business development and decent job creation in the waste sector in the Free State. Research Report for a Study Completed for the South Africa SME Observatory, hosted by the Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental affairs of the Free State Province (DETEA) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO), December 2012 [Online] Available: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_195724.pdf. [Accessed: 15/11/2014]. [ Links ]

SEAGER, J.R. & TAMASANE, T. 2010. Health and well-being of the homeless in South African cities and towns. Development Southern Africa, 27(1):63-83. [ Links ]

SMITH, H. 2008. Searching for kinship: the creation of street families among the homeless youth. American Behavioural Scientist, 51(6):756-771. [ Links ]

SMITH, J. 2010. Capabilities and resilience among people using homeless services. Housing, Care and Support, 13(1):9-18. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2011. Census 2011. [Online] Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/p03014/p030142011.pdf [Accessed: 15/11/2014]. [ Links ]

TIPPLE, G. & SPEAK, S. 2005. Definition of homelessness in developing countries. Habitat International, 29:337-352. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS CENTRE FOR HUMAN SETTLEMENTS (UNCHS). 2000. Strategies to combat homelessness. [Online] Available: http://www2.unhabitat.org/programmes/ housingpolicy/documents/HS-599x.pdf. [Accessed: 17/11/2014]. [ Links ]

VILJOEN, J.M.M. 2014. Economic and social aspects of street waste pickers in South Africa. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

WOOD, B. 2010. Narrowing the gap: an integrated approach to improving food security of vulnerable and homeless people [Online] Available: http://secondbite.org/sites/default/files/NarrowingTheGapAnIntegratedApproachto ImprovingFoodSecurityforVulnerableandHomelessPeople.pdf. [Accessed: 12/01/2016]. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION (WHO). 2014. Food Security [Online] Available: http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/. [Accessed: 10/01/2015]. [ Links ]