Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 n.2 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-567

ARTICLES

The challenges experienced by Zimbabwean social workers practising in Gauteng townships

Clarity MangenaI; Ajwang WarriaII

IPostgraduate student

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Ajwang.Warria@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

South Africa has seen increasing numbers of skilled and unskilled migrants coming into the country legally and illegally. Social work is a global profession and some of the skilled migrants coming to South Africa are social workers with foreign qualifications. This qualitative research was motivated by the need to understand the challenges faced by Zimbabwean social workers who are practising in a township in Gauteng province. Findings indicate that foreign social workers face challenges trying to navigate the work space in South Africa. This study makes a contribution to debates on the migration of professionals as an important policy issue for South Africa.

INTRODUCTION

International migration flows seem to have increased considerably over the past few years (Wojczewski et al., 2015) and this continues to be a crucial aspect of global agendas as it has vast socio-economic and cultural implications for both sending and receiving countries (Kul, n.d.). The mobility of workers worldwide, as in South Africa, is an increasingly important phenomenon and social workers are part of this global trend. Indeed, according to Beddoe and Fouché (2014:i193), "mobile practitioners are navigating the opportunities and challenges by working and living in countries other than where they obtained their professional qualification".

Globalisation has also been heralded as a push factor in the migration for work purposes. Other causes that make people pursue work opportunities outside their countries of origin include high unemployment rates there, poor economic conditions, low wages and lack of opportunities, desire to gain international experience, and improved lifestyle (Tevera & Chikanda, 2009). Countries which have been documented as receiving a lot of labour migrants include the UK, Australia, Canada and South Africa, whereas the sending countries are Mexico, Philippines, China, Zimbabwe, Somalia, Nigeria, India and Ethiopia. Labour migrants currently in South Africa have been reported to come mainly from Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Malawi, Ethiopia, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Numerous studies on migration and development have focused on the migration of unskilled migrants (Khan, 2008; Mawadza, 2008; Neocosmos, 2010), whereas the number of studies on skilled migrants is limited (Dodson, 2001; Rasool & Botha, 2011; Tinarwo, 2011).

Evans, Huxley and Munroe (2006) reported that skilled migrants face challenges in countries of resettlement and working in a new country requires adaptation. For adaptation to be successful, Olivier and Govindjee (2013) and Mupedziswa (2015) recommend that legal responses should ensure protection of migrant's rights and access to social protection. World Bank reports and Bamu's (2015) study report that labour migration (whether formal or informal) impacts on development and policies. Studies in South Africa have focused on the experiences of unskilled migrants and the challenges that they face (Crush & William, 2003; Everett, 2011; Neocosmos, 2010). However, studies on skilled migrants by Bartley et al. (2011), Evans et al. (2006) and Castles and Miller (2003) indicate that migrants make positive contributions to the economies of countries of resettlement, yet this rarely gets recognition and their contributions are mostly perceived negatively.

TRANSNATIONAL/ INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL WORK

International social work is an aspect of social work which allows "flexibility in considering a variety of practices and structures. It enables the discussion to include, for example, a situation in which a social worker goes from one country to another country in order to practice" (Hugman, 2010:13). Warria, Nel and Triegaardt (2015) assert that internationalisation and globalisation affect social workers and they become involved in social service initiatives related to providing care outside their countries of origin through transnationalisation of care and/or globalisation of practice. Other studies by Negi and Furman (2010), Roestenburg (2013) and Hessle (2007) have looked at social work practice in the context of migration, globalisation, international development work and integration of immigrants in host countries.

Yeates (2011) studied transnationalisation of care, and Moriarty, Hussein, Manthorpe and Stevens (2012) researched trends in international labour mobility with a specific focus on social workers. A later study by Hanna and Lyons (2014) looked at European social workers practising in England and highlighted the "local realities" that social workers are expected to intervene in, yet their training might not have entirely provided for that. This study by Hanna and Lyons (2014) built on a study by Pullen-Sansfacon, Brown and Graham's research (2012a), which emphasised the importance of understanding professional and context-specific adaptation processes of international social workers.

The findings from a study on transnational social work in New Zealand (Bartley, Beddoe, Fouché and Harington, 2012) indicate that in as much as the social workers were able to make good use of wide-ranging professional training and skills, they complained about the provision and the varied consistency of quality induction. In addition, Bartley et al. (2012) report that although registration with professional social work bodies is not compulsory, when foreign social workers engaged with the process, they found it to be time-consuming and expensive. Several studies have also indicated that highly structured employment induction is necessary universally for transnational social workers (Bartley et al., 2012; Simpson, 2009; Tinarwo, 2011; Welbourne, Harrison & Ford, 2007; kry nie in bibliografie White, 2006). Zanca and Miscas's (2016) study highlighted social workers' challenges as related to adjusting culturally and the study also noted differences in policies, procedures and systems, which supports earlier findings by Firth (2004) that social work training does not necessarily enable social workers to migrate easily and practise smoothly. Indeed, how a social worker practises will be influenced by the culture and the specific cultural reference points in a given country context (Simpson, 2009). The challenges identified by Bain and Evans (2013) in studying German social workers in England include language challenges, bureaucracy (e.g. system structured around procedures, hierarchies and control), adaptation of professional training (skills and knowledge) and the absence of a culture of professional dialogue in teams. In a multi-country study focusing on South Africa, Canada and England, Pullen-Sansfacon, Spolander and Engelbrecht (2012b) report challenges to include recognition of qualifications, adjustment to new role, integration into the workplace, discrimination during job searches and, on a personal level, exclusion from team decision making, for example. In Bolzman's (2015) study on the diverse transnational practice dimensions of social workers in Switzerland the implication seems to be that challenges could arise from the social workers' different social trajectories, experiences and resources, and their understanding of the social work profession. Migrants worldwide have been perceived as vulnerable, but they can also be actors of social work practices and contribute to innovative interventions (Bartley et al., 2012; Bolzman, 2015; Kul, n.d.).

A literature search reveals that not much has been written about the migration of social workers into South Africa, but more on why social workers want to leave or have left South Africa. Experiences of South African social workers in the UK were explored by Naidoo and Kasiram (2006) and the reasons for leaving South Africa included high case load, lack of resources, resistance and need for security when entering high-risk areas, and dissatisfaction with service conditions. The benefits mentioned have been echoed in other international studies such as those by Bartley et al. (2012) and Tinarwo (2011); they include upward mobility and professional development, supervision and improved working conditions. However, transnational social workers from South Africa identified challenges related to social isolation, inability to perform cultural and spiritual rituals, bureaucratic work structures and professional jealousy (Naidoo & Kasiram, 2006).

In South Africa a major study was commissioned by the Department of Labour that looked at social work as a scarce and critical skill (Earle, 2008). The study reported that in October 2005, according to statistics from the South African Council for Social Services Professions (SACSSP), there were only about 11,100 social workers registered in South Africa. This statistic is a matter of concern in relation to the ever-increasing social challenges faced by individuals, families and communities in South Africa as well as the high turnover rate for social workers. High caseloads have also been reported in social workers leading to burnout and frustration, resulting in most of them either leaving the profession altogether or emigrating to practise in other countries such as the UK and Australia (Engelbrecht, 2006). In the light of this, South Africa has been able to absorb social workers from other countries, especially from Zimbabwe. Other countries such as New Zealand, Canada, the UK and Australia have also been actively recruiting social workers to fill shortages that cannot be met internally (Bartley et al., 2012; Pullen-Sansfacon et al., 2012b). Tinarwo (2011) conducted a study on Zimbabwean social workers in the UK. However, a gap in the research has been noted in relation to work-related experiences of international (especially Zimbabwean) social workers in South Africa. In as much as social work is heavily context-dependent, and responses and resources to attend to people's needs vary according to local circumstances, it would be interesting to gain an understanding on the challenges experienced by Zimbabwean social workers in Gauteng. This is because Zimbabweans are the largest group of foreigners in South Africa (Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP), 2007; Ngomane, 2010), while anecdotal evidence also suggests that the majority of foreign social workers recently registered and practising in South Africa are from Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwean Financial Gazette (2016) recently highlighted that Zimbabwean-trained social workers are shunning the profession and either leaving the country to practise elsewhere or changing professions. It is hoped that this study will contribute to debates on and the practice knowledge of international social work, especially in South Africa.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was adopted for the study to harness rich details of the lived experiences of the participants. A narrative research design was used in the study, as it is assumed that people's lives encompass a variety of untold stories about events that have either a positive or a negative impact on them. This research design was effective because it provided more holistic accounts and views of the individuals and their lived experiences.

Triangulation of sampling was applied and two non-probability sampling techniques were used:

-

Purposive sampling: this was based on the judgement of the researcher in identifying study participants with knowledge of practising social work in a township; and

-

Snowball sampling: the researcher requested the first few participants identified using purposive sampling to provide names of other social workers working in the township (Strydom & Delport, 2012).

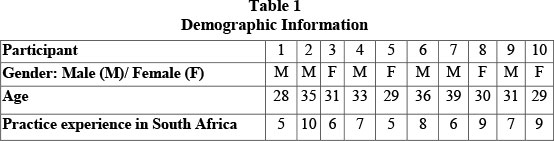

The selection criteria used were that the social workers should be registered to practise with the SACSSP, should have Zimbabwean citizenship, should have been working in the township for at least one year, and were willing and available during the data-collection period. For the entire study 10 participants were interviewed. The demographic information is provided in the table below.

Individual, in-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview schedule (Creswell, 2002) and in English language. The interview schedule consisted of several questions and supported the narrative research design of the study (Bryman, 2004). However, this paper is based on the participants' responses to the following interview question: "What kinds of challenges have you and/or your Zimbabwean colleagues faced whilst working in South Africa?" All the interviews were audio-recorded, with the participants' consent, and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Participation in the study was voluntary and the participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand's Human Research Ethics (Non-Medical) Committee prior to data collection. Informed consent was granted by all study participants. To protect participants' privacy, they are identified using codes and the name of the township where they practised has been withheld.

The first author of the article collected the data for the study. The author is a Zimbabwean citizen, female, in her early twenties and was studying at a South African university, with family working in the health and social care field in the UK. The author was able to recruit the study participants with ease because they were from the same country. However, she maintained objectivity throughout the study through debriefing with her research supervisor regularly, as she could identify with some of the issues being raised by the study participants.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The researcher used a small, purposively chosen population sample that had rich information and which was likely to elucidate responses to the interview schedule. Therefore the findings in this study cannot be generalised to a larger population. In addition, another limitation was the sampling bias. This study may not reflect the experiences of other foreign social workers practising in other South African townships as it focused only on a small number of Zimbabwean social workers practising in townships in Gauteng Province.

INTEGRATED DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

Leaving one's country of origin to go and work in another country is not an easy decision. In addition, it is not guaranteed that once a person gets a job that everything is going to run smoothly. Some of the challenges that the Zimbabwean social workers highlighted in this study, which will be discussed next, include: registration with SACSSP, unfair labour practices, language adaptation, hostility from the local community and safety concerns.

Practice registration with professional body

The Zimbabwean social workers interviewed mainly studied in Zimbabwe and thus had to apply to the social work professional body to be allowed to practise in South Africa. This is what Papadopoulos (2016) has referred to as the politics of recognition, which can be found worldwide in the context of migrating qualifications. The participants in this study reported that the professional registration process was appalling and lengthy, and most of them were constantly frustrated. Generally, all participants reported that registration costs are high, the SACSSP has poor communication structures and follow-up procedures, and that once registration is granted, the body does not assist these professionals to integrate or monitor their practice. These view are illustrated in the following comments:

"One challenge is the registration process with the South African council. Somebody who is a foreigner and who obtained a social work degree in any South African [institution] gets registered easily, but for someone who received his/her qualifications outside the country, it's a very long, lengthy and tedious process. It took me close to a year. They will give you assignments and then call you for an interview. All these stages require money and it's quite a challenge." (Participant 7).

"I know of my colleagues who are were very frustrated by the Council because it took forever - some a year or even two years. I think it is important to check on whether that person's knowledge suits the South African context, but they [SACSSP] should try to improve on their processes." (Participant 2)

South-to-south migrant professionals can especially be affected by professional registration processes as shown by findings from this study. According to the SACSSP annexure for registering foreign social workers, the purpose is to assess foreign-qualified social workers with the view of registering them as social workers to enable them to practise in South Africa. In as much as this process was deemed to be important in terms of establishing competences, the process was found to be unnecessarily lengthy and costly. These frustrations, as a result of temporary deskilling, with the wait for registration, were also noted in the study on female physicians and nurses by Wojczewski et al. (2015). In a study by Pullen-Sansfacon, Brown, Graham and Michaud (2014) the frustrations reported by internationally educated social workers were linked to labour mobility and immigration policies. Thus, professional career developments and the provision of crucial services can be jeopardised during these crucial processes.

The interview is to determine a fit for both the applicant and the registering body. However, as reported, during registration the communication from SACSSP seems irregular and applicants are not updated on what is going on and the nature of the interview. Thus, it might come across as if no one cares about what these professional social workers bring to South Africa and other countries of destination, but the focus and checks are more on the need for them to fit in. According to Bartley et al. (2012:6), "transnational social workers come with a range of qualifications and practice competencies and experiences that may not only contribute to the local professional context, but indeed expand it as intervention models and skills sets developed overseas are able to be put into practice in new settings." Through monitoring the social workers' practice, cross-learning may occur and this can bring benefits to the local social work professional body in terms of curriculum improvements and to the communities where the international social worker practises.

Unfair labour practices

The other challenge described by participants is related to unfair labour practices by employers. This limits their professional growth and development. Participants indicated that their desire to work in different fields of practice or in certain entities was hindered by the conditions of employment or application requirements which tend to exclude foreign nationals. In addition, participants also indicated that some employers perceive them as undeserving, desperate and exploitable. The comments below indicate some of the unfair practices:

"Employment opportunities appear very limited to foreigners because right now we are … restricted to work in NGOs. This is because the government opts for their locals and most of the job adverts require a South African ID, and so it is only restricted to locals and those few that have permanent residency. Despite that, I remember this organisation that I was working for, it wanted to retrench people, and I was the first target despite the fact that I had worked there longer more than [all] my [other South African] colleagues." (Participant 5)

"I think as a foreigner, despite the fact that you are illegal or not, you are a social worker or accountant, one is always subjected to discriminatory practice. If you work in an organisation, there are certain things that don't apply to you as a foreigner. For example, you are told that because you are a foreigner, you don't qualify for this but other employees at the same organisation are benefitting. However, because you need help [to earn a living], you stay put. One example, when it comes to leave days, we only qualify for 15 [leave] days the whole year. So it's quite disturbing because all other local employees qualify for 21 leave days." (Participant 3)

These findings show that many sectors which have absorbed these economic migrants perceive them as underserving, not entitled, and it is clear that these labour migrants may possibly also lack social protection. According to Neocosmos (2010), local employees hold the view that foreigners need to understand that they are here as a courtesy and that priority needs to be given to the citizens of the country first. However, a recent South African study by Schippers (2015) indicates criteria-based employment of foreigners but does not prioritise nationality preference. Indeed, both of these aspects, if not well managed, may still result in non-standardised employment opportunities with conditions which are tantamount to exploitation of migrant workers. A study by Rochman (2009) on foreign migrant employees in Europe indicates that they were exploited, and the employers maximised their profits by heavy deductions and tax. The findings from this study indicate that some leave and dismissal policies are not being followed or interpreted accurately as determined by the labour legislation in the country. Thus, organisations can also be systemic perpetrators of certain injustices, or they can choose to engage in social action and protect the vulnerable (Okyere-Manu, 2016).

Language as a work barrier

Prior to arrival in South Africa, all participants confirmed that they were fluent in Shona and/or Ndebele and English. The participants felt that when they started working, language remained a challenge for them. Although Ndebele and English are two of the 11 official languages in South Africa, it was not guaranteed that those would be the languages of communication at their work settings. According to the participants, the language barrier manifested in instances when they are intervening with clients as shown below:

"There are challenges. To begin with, language [can be a] barrier [as] there are so many languages here in South Africa, for you [as] a foreigner coming from Zimbabwe and you know English is not even one of the townships languages, so you are trying to find a most suitable language or an easy language that you can learn [for work purposes]. I have learnt Zulu over the years and I had to do it from the internet. Then comes a Sotho-speaking client and then you are stuck. You know Zulu and this person maybe doesn't know Zulu and you try to meet half way with the client, then you have to look for an interpreter and sometimes, it's not readily available with the organisations like this, so language is one of the main challenges in working in townships. (Participant 3)

In the light of the above finding, the valuable role that language plays in intervening with clients should not be undermined. Gauteng is considered to be a cosmopolitan province with increasing internal migration from other provinces or parts of South Africa. Thus, there is a high likelihood of working with clients who speak other South African languages and not only Zulu, Sotho and English as the official languages of the province. Though adaptation and acculturation during labour mobility can be language dependent (Pullen-Sansfacon et al., 2014), learning or having a common language could still lead to cultural misunderstandings (Beddoe & Fouché, 2014).

In addition, the inability to speak a similar local language with social work colleagues was also reported and highlighted as a factor through which colleagues consciously isolated foreign social workers from professional conversations.

"I have seen in terms of language barriers, as I highlighted earlier that I am not really fluent, I'm still learning … IsiZulu and Sotho. There are times when maybe you meet with other social workers, let's say maybe in meetings organised by the department or another service provider. The moment you start expressing yourself in English, there are these [hostile] looks that you get from [other] people and I find it very demeaning. When you keep on speaking in English, they keep on speaking vernacular languages even though they know that you don't understand it" (Participant 9)

The comment above indicates that unreceptive behaviour can be manifested in the form of a different language being used in the presence of foreign social workers within the work place or in social work meetings and symposiums. Thus, workplace discussions and professional conversations which could be developmental in nature may end up being exclusionary. A social exclusion perspective provides insight into the attitudes of South African social workers (in-group) versus foreign social workers (out-group). Because they define local culture as paramount, South African social workers respond less favourably and they apply existing (conscious and unconscious) prejudices to the foreign social workers (Roestenburg, 2013). The social work profession strives to improve individuals' and families' quality of life as well as uplift and contribute towards functional communities and promote social justice. The unfriendly behaviour reported in the finding is based on the attitude of the co-workers and it further shows that, even though social workers are trained to fight social injustices, no environment is safe from hostile behaviour and oppression (Hanna & Lyons, 2014; Wojczewski et al., 2015). Indeed, knowingly and/or unknowingly, social workers themselves can be perpetrators of the same injustices they are supposed to be fighting and such perceptions can explicitly or subtly find their way into policies (Roestenburg, 2013).

Hostility in practice community

The study participants reported not feeling generally welcomed in the communities where they render services. The reception was cold from the start, especially if the community members suspected that the social worker was not from South Africa. Hostility was evident in the participants' shared work experiences and further elements of unfriendliness could also be inferred from their narratives. Findings from this study indicate that the Zimbabwean social workers were viewed with suspicion and hostility, even though they were in the community to offer legitimate work in form of much needed professional social services. The majority of the study participants reported that they were subjected to negative perceptions and lack of trust from numerous individual, group or family clientele, as illustrated in the following comments:

"Sometimes when you introduce yourself, as a foreign social worker, some of these local people have their own perceptions about foreign nationals. I will give you an example. When you approach a client and say, "May I have a copy of your ID [identity document]" because we want to do the court [statutory] paper work … they usually think this is a scam or some sort of fraud. I have faced such, and [then] I had to explain that the ID is being taken for official use only." (Participant 1)

"I think if I was a local social worker, I will be able to relate with my clients much easier, because they can trust me, it's someone that they can identify with. Remember, the helping relationship is built on the level of trust that the client has on you. So despite the level of competence, I think place [i.e. social worker's country] of origin may impact on the level of trust that is developed between the social worker and the client." (Participant 4)

"Yes, overtime, the attitudes of local nationals have made life difficult for me as a social worker when I am conducting my home visits, because you know Soweto [township] is a very big area, and I didn't study here, didn't grown up [here], so I don't know the place very well and in many times when I ask for directions in English, or broken Zulu, I have not been assisted." (Participant 6)

The quotations indicate that the hostile behaviour can be found in the public sphere. These sentiments support Neocosmos's (2010) argument that the general South African public largely holds negative attitudes and perceptions of foreigners, irrespective of how they came into the country and the positive economic and/or social contributions they might be making. Public action against foreigners is usually linked with perceptions that foreigners are a threat to socio-economic security, that they commit crime and take jobs (Ngomane, 2010). The fact that unemployment is high in South Africa might also impact on skilled foreigners' work experience (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2010; Mamabolo, 2015; Di Paola, 2012). The findings in this study support those of a previous study in New Zealand by Bartley et al. (2011), which shows that workplace discrimination, exclusion and the economic exploitation of immigrants is a worldwide phenomenon that is not peculiar to South Africa. The violation of rights of skilled professionals outside their countries of origin is a negative phenomenon worldwide despite the contributions that they might be making to the economy of the country of resettlement.

Similar findings related to hostility are reported in a Canadian study on overseas-educated social workers and it affected subsequent professional recognition (Pullen-Sansfacon et al., 2014). From a system's perspective, since professional adaptation intersects with personal, social and cultural identity in a person's life, in communities where social workers encounter positive welcoming attitudes, acculturation has been found to be much easier and they have enjoyed the international work experience. This was evident in the study by Beddoe and Fouché (2014).

Concern for safety

It is evident from the data collected that the interviewed social workers live in constant fear and they are scared of being victims of xenophobic attacks. With regards to this finding, most participants pointed to the xenophobic attacks which happen sporadically in South Africa. They highlighted that they rarely felt safe working in the township, especially considering the fact that that is where the attacks usually begin. The study participants highlighted that somehow this fear sometimes compromises the quality of services that they render to their clients as they will be preoccupied with their own personal safety.

"The hostile attitudes of locals make us feel unsafe in these communities where we supposed to render our services to because of fear of being attacked. As a foreign national, you just want to conduct the session during your home visit faster, so that you can leave because you don't know what's going to happen to you." (Participant 5)

"In as much as I love my job, I however fear for my life working especially in townships. If it wasn't for the issue of bread and butter, and putting food on the table for our families, and having another option, I would definitely not want to work in townships."(Participant 2)

The fear that comes with being a foreigner and working in townships seems to compromise the interventions of the social workers. The participants feel obliged to offer their services because they are passionate about social work and they also want to earn a living, but are scared and fearful when offering these services and therefore they do not give their all. Deter (2009), Roestenburg (2013) and Mamabolo (2015) point out that with the emerging new-nation discourses, the foreign/international social workers find themselves at a site where identity, racism and other oppressive practices and violent practice are reproduced. The construction of the South African national identity was based on a fragile sense of superiority in relation to that of other African countries, hence deserving of protection (Jearney-Graham & Bohmke, 2013; Schippers, 2015). Thus, it is not hard to see and understand why there is fear even in the case of social workers who are genuinely providing care and social services.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

According to Naidoo and Kasiram (2003), South Africa is in the midst of a serious social worker shortage. The social problems in South Africa are structural in nature and they impact on individuals and families; this has subsequently translated into a high demand for social service professionals. In the light of this, the migration systems approach emphasises the links between both sending and receiving countries which are characterised by a transactional history of collaboration and support as well as acknowledgement that skills shortages are not a challenge that can be resolved quickly. The migration approach is informed by loss of skills from South Africa, the changing nature of the South African social service and welfare field, the nature of international and neighbouring labour markets, and worldwide competition for skilled labour.

Migrants worldwide face several challenges in the country of resettlement and these challenges are therefore not peculiar to South Africa. Indeed, according to Beddoe and Fouché (2014: i200), resettling and finding employment in a new country is only an example of the many challenges international social workers face. This study was able to illustrate that learning a language and the social norms of the community of practice are essential, and that it is also vital to be aware that the general acculturation process, and that adjusting to the professional and workplace culture in a new country requires preparedness as well.

Castles and Miller (2003) further regard family, support structures, the community and the environment - for example, the language and cultural systems in the receiving country - as important factors determining the work place experiences and adjustment mechanisms of migrants. Structures and systems can also fulfil mediation roles between migrants and political, social and economic conditions. For example, as recommended in the Bartley et al. (2012:9) study, the South African social work professional body can streamline the registration process for international social work applicants already registered in their countries by merely accepting and transferring registration from countries of origin, after investigation whether there has been misconduct. In addition, the different professional bodies can have agreements based on mutual recognition, thus alleviating frustration of registration. Furthermore, there is a need for professional induction. However, further research is needed on what ought to be included in the induction programme and how it should be delivered.

Implicit or explicit workplace tensions between migrants and host social workers, and in communities of practice between clients and social workers, can have negative consequences on professional confidence and challenges in negotiating new professional, social and cultural contexts. Discrimination and other unfriendly behaviours make the struggle for integration, creating a positive social and professional environment, even more difficult than it already is for transnational migrants (Wojczewski et al., 2015:14). An anti-discrimination consensus in the social work organisations employing international social workers in South Africa is evidently missing. This is a matter of great concern, as social work is a human rights profession that sets out to fight social injustices. A good practice from the United Nations Population Fund, reported on in the study by Wojczewski et al. (2012), is also applicable to this study. That is, there is a need to promote better knowledge, perceptions and representation of migrant communities in order to foster more consistent integration of migrants into civil society, and an improvement of integration through sensitisation and training.

In as much as social workers are trained to be conscious of cultures, it is crucial to recognise that there are multiple understandings of social work and that it is not really a universal profession with universal values (Beddoe & Fouché, 2014). This study has shown that interpretation happens through different lenses, which may manifest in a range of challenges that confront transnational social workers (Bartley et al., 2012; Pullen-Sansfacon et al., 2012b).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the authors echo the sentiments of Bartley et al. (2012:2), who reiterate that transnationalisation of professional social workers will continue to challenge governments and social service employers, and that there ought to be improvements in ways of indicating greater understanding and engagement with transnational social work as a complex transnational professional space. It is crucial to listen to these narratives of everyday professional discrimination to understand the magnitude of hostility and to raise awareness of unfair treatment. Policy strategies are necessary with regards to integration of skilled migrants into the labour market and generally working towards anti-discriminatory practices. In addition, relevant stakeholders should co-develop and reconceptualise transitional professional spaces to offer opportunities and growth and development, and not only generate challenges.

REFERENCES

BAIN, K. & EVANS, T. 2013. The internationalization of English social work: the immigration of German social work practitioners and ideas to England. Research Report. Royal Holloway University of London. [ Links ]

BAMU, P. 2015. "I carry people and goods across the border for a living": The role and regulation of informal cross-border couriers (bomalayisha) in the Zimbabwean-South Africa corridor. [Online] Available: http://www.saspen.org/brief/SASPEN-brief_2015-4_Pamhidzai-Bamu_The-role-and-regulation-of-Informal-cross-border-couriers.pdf. [Accessed: 29/06/2016]. [ Links ]

BARTLEY, A., BEDDOE, L., FOUCHÉ, C. & HARINGTON, P. 2012. Transnational social workers: making the profession a transnational professional space. International Journal of Population Research. [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/527510. [Accessed: 14/02/2016]. [ Links ]

BARTLEY, A., BEDDOE, L., FOUCHÉ, C. & HARINGTON, P. & SHAH, R. 2011. Crossing borders: key features of migrant social workers in New Zealand. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 23(3):16-30. [ Links ]

BEDDOE, L. & FOUCHÉ, B.C. 2014. 'Kiwis on the move': New Zealand social workers' experience of practising abroad. British Journal of Social Work, 44(1):i193-i208. [Online] Available: doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu049. [ Links ]

BOLZMAN, C. 2015. Immigrant social workers and transnational practices: the example of Latin Americans in Switzerland. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 13(3):281-301. [ Links ]

BRAUN, V. & CLARKE, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

BRYMAN, A. 2004. Social research strategies (2nd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CASTLES, S. & MILLER, M.J. 2003. The age of migration: international population movements in the modern world. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2002. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

CRUSH, J. & WILLIAMS, V. 2003. Criminal tendencies: immigration and illegality in South Africa. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 10. SAMP. Cape Town. [ Links ]

DETER, P. 2009. Identity, agency and the acquisition of professional language and culture. Canada: University of Toronto. [ Links ]

DI PAOLA, M. 2012. A labour perspective on xenophobia in South Africa: a case study of the metal and engineering industry in Ekurhuleni. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. (MA Research Report) [ Links ]

DODSON, B. 2001. Gender and brain drain. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 23. SAMP. Cape Town. [ Links ]

EARLE, N. 2008. Social work as a scarce and critical profession: scarce and critical skills research project. Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU) and Sociology of Work Unit Research Consortium. Research commissioned by the Department of Labour, South Africa. [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT, L.K. 2006. Plumbing the brain drain of South African social workers migrating to the UK: challenges for social service professions. Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 42(2):127-146. [ Links ]

EVANS, P., HUXLEY, S. & MUNROE, M. 2006. International recruitment of social care workers and social workers in UK and Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Journal of Social Work, 40(1/2):93-110. [ Links ]

EVERETT, D. 2011. Xenophobia, state and society in South Africa, 2008-2010. Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 38(1):7-36. [ Links ]

FIRTH, R. 2004. Enabling social workers to work abroad. Paper presented to the IASSW/IFSW Conference Adelaide, Australia. [ Links ]

FORCED MIGRATION STUDIES PROGRAMME (FMSP). 2007. Responding to Zimbabwean migration in South Africa: evaluating options. University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

HANNA, S. & LYONS, K. 2014. Challenges facing international social workers: English manager's perceptions. International Social Work. [Online] Available: doi: 10.1177/0020872814537851. [ Links ]

HESSLE, S. 2007. Globalisation: implications for international development work, social work and the integration of immigrants in Sweden. In: DOMINELLI, L. (ed), Revitalising communities in a globalising World. Farnham: Ashgate. [ Links ]

HUGMAN, R. 2010. Understanding international social work: a critical analysis. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [ Links ]

JEARNEY-GRAHAM, N. & BOHMKE, W. 2013. "A lot of them are good buggers": the African "foreigner" as South Africa's discursive other. PINS, 44:21-41. [ Links ]

KALITANYI, V. & VISSER, K. 2010. African immigrants in South Africa: job takers or creators? South African Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 13(4):376-390. [ Links ]

KHAN, F. 2008. South African policy in the face of xenophobia-migration. [Online] Available: www.migrationpolicy.org/articles/south-africa-policy. [Accessed:15/06/2016]. [ Links ]

KUL, Y. n.d. Opportunities and challenges of international migration for sending and receiving countries. [Online]. Available: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/opportunities-and-challenges-of-international-migration-for-sending-and-receiving-countries.pdf. [Accessed:17/11/2016]. [ Links ]

MAMABOLO, M.A. 2015. Drivers of community xenophobic attacks in South Africa: poverty and unemployment. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(4):143-150. [ Links ]

MAWADZA, A. 2008. The nexus between migration and human security Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Paper 162:1-12. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies (ISS). [ Links ]

MORIARTY, J., HUSSEIN, S., MANTHORPE, J. & STEVENS, M. 2012. International social workers in England: factors influencing supply and demand. International Social Work, 55(2):169-184. [ Links ]

MUPEDZISWA, R. 2015. Migration and social protection: the experiences of undocumented Zimbabwean national based in the UK. SASPEN Brief 3/2015. [Online] Available: http://www.saspen.org/brief/SASPEN-brief_2015-3_Rodreck-Mupedziswa_Undocumented-Zimbabweans-in-UK.pdf. [Accessed: 29/06/2016]. [ Links ]

NAIDOO, S. & KASIRAM, M. 2003. Social work in South Africa: Quo vadis? Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 39(4):372-380. [ Links ]

NAIDOO, S. & KASIRAM, M. 2006. Experiences of South African social workers in the UK. Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 42(2):117-126. [ Links ]

NEGI, N.J. & FURMAN, R. 2010. Transnational social work practice. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

NEOCOSMOS, M. 2010. From "foreign natives" to "native foreigners": explaining xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa. Citizenship and nationalism, identity and politics. Dakar: Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA). [ Links ]

NGOMANE, S.T. 2010. The socio-economic impact of migration in South Africa: a case study of illegal Zimbabweans in Polokwane Municipality in the Limpopo Province. Polokwane: University of Limpopo. (MA Thesis) [ Links ]

OKYERE-MANU, B. 2016. Ethical implications of xenophobic attacks in SA: a challenge to the Christian church. Cross Currents, 66(2):227-238. [ Links ]

OLIVIER, M. & GOVINDJEE, A. 2013. Labour rights and social protection of migrant workers: in search of a coordinated legal response. Paper presented at the Labour Law Research Network Inaugural Conference in Barcelona. [ Links ]

PAPADOPOULIS, A. 2016. Migrating qualifications: the ethics of recognition. British Journal of Social Work, 0: 1-19. [Online] Available: doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcw038. [Accessed: 25/06/2016]. [ Links ]

PULLEN-SANSFACON, A., BROWN, M. & GRAHAM, J. 2012a. International migration of social workers: toward a theoretical framework for understanding professional adaptation processes. Social Development Issues, 34(2):37-50. [ Links ]

PULLEN-SANSFACON, A., SPOLANDER, G. & ENGELBRECHT, L. 2012b. Migration of professional social workers: reflections on challenges and strategies for education. Social Work Education, 31(8):1032-1045. [ Links ]

PULLEN-SANSFACON, A., BROWN, M., GRAHAM, J. & MICHAUD, A.D. 2014. Adaptation and acculturation: experiences of internationally educated social workers. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 15(2):317-330. [ Links ]

RASOOL, F. & BOTHA, C.J. 2011. The nature, extent and effect of skills shortages on skills migration in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA [Online] Available: doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v9i1.287. [Accessed: 25/06/2016]. [ Links ]

ROCHMAN, M. 2009. Determinants of nurse fluidity: A theoretical model to examine processes to support foreign educated nurse integration to the US healthcare system. Academy Health Meet, 26:1008-1009. [ Links ]

ROESTENBURG, W. 2013. A social work practice perspective on migration. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(1):1-21[Online] Available: doi.org/10.15270/49-1-72. [Accessed: 05/04/2017] [ Links ]

SCHIPPERS, C.S. 2015. Attitudes towards foreigners in South Africa: A longitudinal study. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. (MA Thesis). [ Links ]

SIMPSON, G. 2009. Global and local issues in the training of "overseas" social workers. Social Work Education, 28(6):655-67. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2012. Sampling and pilot study in qualitative research. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grassroots: for the social service professions (4th ed). Cape Town: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

TEVERA, D. & CHIKANDA, A. 2009, Migrant remittances and household survival in Zimbabwe. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 51. SAMP. Cape Town. [ Links ]

TINARWO, T. 2011. Making Britain home: Zimbabwe social workers' expereinces of migrating and working in a British city. Durham: Durham University. (Doctoral Thesis) [ Links ]

WARRIA, A., NEL, H. & TRIEGAARDT, J. 2015. Challenges in identification of child victims of transnational trafficking. Practice: Social Work in Action, 27(5):315-333. [ Links ]

WELBOURNE, P., HARRISON, G. & FORD, D. 2007. Social work in the UK and the global labour market. International Social Work, 50(1):27-40. [ Links ]

WOJCZEWSKI, S., PENTZ, S., BLACKLOCK, C., HOFFMAN, K., PEERSMAN, W., NKOMAZANA, O. & KUTALEK, R. 2015. African female physicians and nurses in global care chain: qualitative explorations from five destination countries. PLoS ONE, 10(6). [Online] Available: e0129464 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129464. [Accessed: 14/02/2016]. [ Links ]

YEATES, N. 2011. Going global: transnationalization of care. Development and Change, 42(4):1109-1130. [ Links ]

ZANCA, R. & MISCA, G. 2016. Filling the gap? Romanian social workers "migration" into the UK. Social Work Review, 1:41-47. [ Links ]