Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 n.2 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-566

ARTICLES

Reflections of social workers on the experiences of pregnant teenagers during group work sessions

Freddy SkobiI; Mankwane MakofaneII

IDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. <makofmd@unisa.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the reflections of 12 social workers, based on group sessions held with pregnant teenagers in the Capricorn district, Limpopo Province. The burden of caring for pregnant teenagers and their children falls on their families and the state, while men, young and old, are not held responsible. Although some of the literature pertaining to the health sector does not recognise or acknowledge social work, the multifaceted challenges facing teenagers, including the prevention of repeat pregnancies during adolescence call for a multidisciplinary and inter-sectoral approach to support these young women. Future research should focus on, among other things, developing resilience among teenagers.

INTRODUCTION

The government, parents, educators, helping professionals and social workers in particular are concerned about the high rates of teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Teenage pregnancy is defined by the United Nations Population Fund as the pregnancy of teenage or underage girl between the ages of 13 and 19 years (UNFPA, 2002). In the United States of America nearly one million teens become pregnant each year (Meade & Ickovics, 2005:661; Sarri & Phillips, 2004:538). Various psychosocial, economic, cultural and family-related factors have led to the alarming rate of teenage pregnancy in this country, which remains high by international standards.

An increase in teenage pregnancies from 1169 in 2005 to 2336 in 2006 was noted in Gauteng, while in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) more than 17000 teenagers fell pregnant in 2010 (Kyei, 2012:134; Rangiah, 2012:1). However, an analysis of provincial trends showed a greater number of learner pregnancies in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo Provinces (Panday, Makiwane, Ranchod & Letsoalo, 2009:11). In 2009 the Limpopo Provincial Department of Social Development (DSD) reported an increase in pregnant teenagers from 6965 to 7754 (DSD, 2011:12). Conversely, in 2010 a 30% decrease in teenage pregnancy in KZN was reported (Radebe, 2013:1). A rate of 13%, twice the national average of 6.5%, was reported in Taung, a rural area in North-West Province (Kanku & Mash, 2010:563). Nearly a third of women have children before they reach the age of 19 or 20 (Department of Education, 2010:1; Mothiba & Maputle, 2012:2).

The prevalence and effects of teenage pregnancy captured the attention of top government officials in Limpopo Province. In 2011 a member of the Executive Council (MEC) for Health and Social Development and Education visited a secondary school in the Mopani District where 12 teenagers were reported to be pregnant. The MEC appealed to social workers to equip teenagers with life skills and to inform them of the consequences of teenage pregnancy (Nduvheni, 2011:1).

Teenage pregnancy has an adverse effect on the wellbeing of teenagers, including a high rate of infant and maternal mortality as well as sex-related diseases such as infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (Kyei, 2012:143; Sodi, 2009:51). Noticeable consequences of teenage pregnancy include dropping out of school, truancy, abortion, child neglect and poverty (Kanku & Mash, 2010:564; Kyei, 2012:143; Sayegh, Castrucci, Lewis & Hobbs-Lopez, 2010:94). As a result of dropping out of school prematurely, teenagers may only be able to find temporary or unskilled jobs and have to rely on welfare to survive (Doğan-Ates & Carrión-Basham, 2007:555). In some instances they may not find or keep a job because of a lack of the necessary skills (Genobaga, 2004:138).

Pregnant teenagers should be viewed as adolescents who experience "the usual turbulence of development and need support and assistance" (Sarri & Phillips, 2004:538). Social workers utilise multilevel intervention strategies through primary and secondary methods to assist pregnant teenagers, who face multiple challenges. Group development comprises five stages: pre-affiliation, addressing issues of power and control, dealing with intimacy, differentiation and separation (Sheafor & Horejsi, 2012:240). Group work is a method of social work practice which recognises and uses processes that occur when two or more people work together towards achieving a common goal (Doel, 2000:148). Toseland and Rivas (2012:11) define group work "as a goal-directed activity" with lesser treatment and task groups "aimed at meeting socio-emotional needs and accomplishing tasks". This activity is directed at individual members of a group as well as at the group as a whole within a system of service delivery. Lindsay and Orton (2012:7) add that group work is a method of social work that "aims, in an informed way, through purposeful group experiences, to help individuals and groups to meet individual and group needs, and to influence and change personal, group, organisational and community problems". Different groups such as therapeutic, psychoeducational, and support groups may be utilised to address the challenges faced by pregnant teenagers.

Thus the group process involves the dynamic interaction among group members to enhance growth and change (Nicholas, Rautenbach & Maistry, 2010:132). This ongoing process includes opinion and information exchange, decision making and support, which creates patterns in relation to roles, norms and conflict management (Nicholas et al., 2010:132). Hence, by universalising the issues that pregnant teenagers face, groups foster an understanding that individuals are not alone in their suffering. Belonging and relating to a peer group reduce anxiety and increase self-expression and the willingness to try new ideas (Drumm, 2006:23; Toseland & Rivas, 2012:33).

The risks and consequences of teenage pregnancy are well documented, but the reflections of social workers who provide group work services are not. It is therefore important to afford them an opportunity to reflect on issues addressed during group sessions.

RESEARCH QUESTION AND GOAL

The broad and overall research question solicits an exploration of the central issue under investigation (Creswell, 2009:129), namely what are the reflections of social workers on the experiences of pregnant teenagers during group sessions? The goal specifies what the research intends to achieve (Braun & Clarke, 2013:53). Thus, the goal of this study was to develop insight into the reflections of social workers on the experiences of pregnant teenagers as expressed during group sessions. Permission to undertake the study in the Capricorn District was granted by the Limpopo Provincial Department of Social Development after approval of the research project by the Unisa Department of Social Work Research and Ethics Committee.

RESEARCH APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

In 2014 a qualitative exploratory-descriptive study was conducted in the Capricorn District, where it had been established that four out of 10 teenagers fall pregnant at least once before they reach the age of 20 (Mothiba & Maputle, 2012:2). Purposive sampling was employed to select 12 social workers who were providing services to pregnant teenagers in rural and urban areas of Capricorn for a minimum of two years. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants after the interview guide had been pilot tested with two social workers who met the inclusion criteria. The outcome of the pilot test led to the modification of two questions. Data obtained from these participants did not form part of the study. The interviews were digitally recorded with the participants' permission after signing a consent form and then transcribed verbatim.

Parallel independent processes of data analysis following Tesch's eight steps (outlined by Creswell, 2009:186) were undertaken by the researcher (first author) and an independent coder. After that a consensus discussion was held by the researcher, independent coder and the supervisor (second author) to determine areas of convergence and divergence in the themes, sub-theme and factors that emerged from the data analysis.

The researcher's conduct was guided by ethical issues related to informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity, and by the principles of data management throughout the project. Bracketing or reflexivity assisted the researcher to develop a non-judgmental and objective attitude towards the information shared by the participants (Doyle, 2013:238-255). The use of multiple sources also gave credence to the study.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

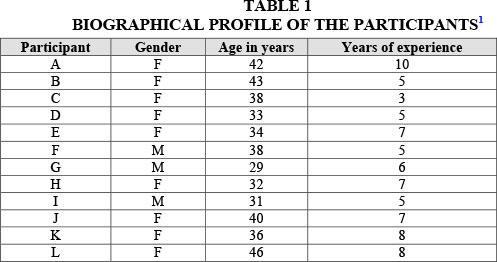

The biographical data of the participants are shown in Table 1 below. Three themes, a sub-theme and the factors that emerged from data analysis are presented.

Nine female and three male social workers took part in the study. Statistics show that women remain in the majority, with men making up between 11% and 13% of the 16121 registered social workers (South African Council for Social Service Professions [SACSSP], 2010:1). The predominance of females is attributed to low salaries, which is a major disincentive for men (Hochfeld, 2002:110; Khunou, Pillay & Nethononda, 2012:122).

The ages of the participants ranged from 29 to 46 years with a mean of 37 years. The participants hold four-year Bachelor of Social Work degrees from different accredited South African universities and are registered with a professional body (South African Council of Social Service Professions). Of the 12 participants, one had enrolled for a master's degree in forensic social work, while another was completing a short course in the employee assistance programme (EAP) at the University of the North-West (Potchefstroom) and the University of Pretoria respectively.

The participants' years of experience ranged from three to 10 years with a mean of six years. Eleven participants had six years working experience and one had three years. The participants' years of experience in the provision of social work services to pregnant teenagers added to the credibility of the findings.

The study was conducted in the Capricorn district of the Limpopo Province, which is predominantly rural and situated in the northern part of South Africa, with a population of 1243,167 (Capricorn District Municipality Spatial Development Framework, 2007:1).

PRESENTATION OF THEMES, SUB-THEME AND FACTORS

The researcher and the independent coder analysed the data independently and then discussed the outcomes with the study supervisor to reach consensus on the themes, sub-theme and factors that emerged from the study.

THEME 1: PARTICIPANTS' VIEWS ON FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO TEENAGE PREGNANCY

Numerous personal and family factors, individually or in combination including a lack of access to health facilities, may lead to teenage pregnancy, even though this is seen as ethically unacceptable or a disgrace, and stigmatised in some communities of South Africa (Matlala, Nolte & Temane, 2014:5). Many educators are displeased with the challenge of implementing a policy that allows pregnant schoolgirls to continue with their schooling (Sibeko, 2012:26). Of the 97 educators in KwaZulu-Natal who participated in the study by Mpanza and Nzima (2010:433), 68% revealed positive attitudes towards teenage pregnancy, while 32% revealed negative attitudes. Gouws, Kruger and Burger (2008:212) are of the view that educators must be prepared and capable of offering emotional support to pregnant teenagers. This matter is debatable as educators may not have the knowledge and skills to provide the necessary services. Instead, helping professions such as social workers are well equipped to offer psychosocial support to these learners.

The participants indicated that personal problems experienced by pregnant teenagers might be exacerbated by peer pressure, a lack of parental control and information on sexuality, economic reasons, cultural practices, intimidation, sexual abuse and barriers to accessing healthcare facilities.

● Peer pressure

Peer pressure is a universal problem. A weekly series of comments by South African pupils elaborating on this phenomenon and other ills in the education system are published in the Mail & Guardian Special Reports section, for example: "Pupils speak out: Peer pressure against using protection" (Swart, 2012:24). Peer pressure manifests itself in different ways.

"She got pregnant when she was visiting her parents during school holidays in Swaziland. Then she was under pressure because most of her peers have children and she wanted to achieve success as a woman as well."

"Some teenagers said when they fail to listen to their parents they opt to listen to their peers."

According to the report on teenage pregnancy in Limpopo Province (2012), 12.8% of teenagers wanted to become pregnant as a result of peer pressure, and 4.4% with unwanted pregnancies also felt compelled to yield to peer pressure (Department of Social Development, 2012:7).

"They will go to the taverns and drink alcohol and when drunk they will go with men who shall have bought them beers and have sex with them. And because they will be drunk they will not remember whether a condom was used or not. They will only realise later that they are pregnant."

Drugs and alcohol use prior to sexual activity can be linked to an indifferent attitude towards the use of contraceptives, thereby increasing risk-taking sexual behaviour and the possibility of an unwanted pregnancy (Panday, Makiwane, Ranchod & Letsoalo, 2009:33; Sibeko, 2012:17). South African families often bear the burden of managing risky behavioural problems among their children who engage in substance abuse and unsafe sexual practices (Flisher & Gevers, 2010:53). Decision making by teenagers may be adversely influenced by the misplaced admiration of friends, as is evident from the comment below.

"One group member said that she once accompanied her friend to collect a child support grant. She saw her buying groceries and beautiful clothes. She said that she felt pressure as she could not afford to buy clothes for herself. Therefore, she was tempted to fall pregnant so that she can also apply for the child support grant."

In some instances, inadequate cognitive development and a lack of important information among teenagers can result in poor problem-solving skills and an inability to plan for the future and make informed decisions.

● Lack of parental control

There seems to be a correlation between a lack of parental supervision (not knowing the whereabouts and activities of their teenagers outside home and school) and teenage pregnancy (Miller, Benson & Galbraith, 2001:9). The following excerpts are illustrative of this trend:

"A teenager aged 15 years explained that her single mother was working in Makhado [town] as a domestic worker, so she would be home alone and lonely. As such, she took advantage of being independent and invited her boyfriend, who kept her company all night, almost every night."

"…. parents flocked to cities such as Gauteng for employment leaving children behind to fend for themselves."

The findings support the notion that a lack of parental care and supervision because of working parents and single parenthood result in teenage pregnancy and early childbearing (Lyon & D'Angelo, 2006:148; Makola, 2011:33; Moliko, 2010:24). A study in Malaysia found that being raised by a single parent exacerbates the risk of adolescent pregnancy (Omar et al., 2010:220). There is also a view that the absence of a father figure is associated with pregnancy among teenagers (Doğan-Ates & Carrión-Basham, 2007:556).

Most single mothers work outside the home environment. Their children know the time their mothers return home and may thus be tempted to engage in sexual activities. Young girls who are not monitored or guided by an adult are exposed to sexual vulnerabilities (Makola, 2011:33; Moliko, 2010:24). This trend is prevalent in Limpopo villages as a result of the lack of employment opportunities. As a result, some teenagers are left alone while parents (one or both) seek employment in towns and cities far from the family home.

● Economic reasons

Older men who entice young girls with gifts in exchange for sex are referred to as "sugar daddies". This label normalises and romanticises a phenomenon which should be condemned considering the negative effects of such practices on teenage girls. The identities of older men who impregnated teenagers are generally not divulged, and they are protected from embarrassment at the expense of innocent children. Furthermore, these older men abdicate their responsibilities as they do not maintain their children in terms of Chapter 4 of the Maintenance Act No. 22 of 2005.

"Men, particularly older men, give them money or buy them expensive items such as cell phones for unprotected sex".

Previous findings reported that older men are often responsible for teenage pregnancies (Mwinga, 2012:29). Having sex for money or gifts has been found to be a common occurrence among girls in many parts of Africa (Kim, 2008:1). Such a practice has generally "been perceived to be a consequence of women's poverty" (Kim, 2008:1). Luke's (2005:6) study also revealed that "sugar daddy" partnerships - men aged 21 to 45 years who have sexual relationships with adolescent girls - characterised by the large age and economic asymmetries - were frequently associated with decreased condom use. Children from poor families become prone to coercive sexual relations where financial reward is exchanged for sex (Makiwane, 2010:193; Sethosa, 2007:10). There is a plethora of information suggesting that poverty may lead some teenagers to engage in unprotected sexual activities (Karra & Lee, 2012:17; Mnyipika, 2014:12; Rangiah, 2012:11).

Child maltreatment occurs in different settings and the perpetrators might be parents (Makoae, Roberts & Ward, 2012:3). The economic and social power enjoyed by men over single women who rely on them for support may place their children at a disadvantage.

"A mother of a teenager pleaded with her daughter and other family members not to open a police case for him [stepfather] because he was supporting them financially. However, I did my job of placing him in the Child Protection Register."

Similar findings are reported by Nhedzi (2013:111), namely that perpetrators of sexual abuse against children are protected by their wives and/or girlfriends. According to the DSD, the Director General should keep and maintain a register called a National Child Protection Register in terms of Section 111 of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005. This means that the social worker completed DSD Form 22 to report that the child has been abused. Such information is kept in the register for future reference. The social worker then submits Form 23 regularly reporting on services provided to the child until termination (Department of Social Development, 2015:4).

● Cultural practices

Cultural norms have shifted and in this modern era being pregnant at an early age is no longer seen as necessarily immoral (Kanku & Mash, 2010:570). However, certain groups of people, including parents, frequently violate the provisions of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005, which stipulates that every child has the right not to be subjected to social, cultural and religious practices which are detrimental to health, wellbeing or dignity.

"…. however she was not happy about it, because she had to prove her fertility as an acceptable norm in her society."

"The teenager said that in her culture they bear children to prove their fertility and … prove their marital value … boyfriends who may be the father of their children may not leave them."

Studies have found that teenage girls may feel the need to prove that they are able to bear children before marriage (Kanku & Mash, 2010:567; Nkwanyana, 2011:14). A strengths approach would enable social workers to identify and recognise the strengths and resilience of every culture in order to assist teenagers to make informed decisions (Benard & Truebridge, 2013:216).

● Intimidation and sexual abuse

Mwinga (2012:29) indicates that "coerced sex is a common phenomenon in African developing countries and is a cause of unprotected sex." Exploitation of teenage girls through intimidation by men in their homes and in schools is a cause for grave concern.

"Some teenagers indicate that because men are physically stronger than them, some men force them to have sex with them so they are afraid to negotiate safe sex."

The power and gender imbalance in relationships leads to unsafe sex and increases the risk of STIs and HIV infection among teenage girls. It is estimated that 4.3% of women aged 15 to 24 in Sub-Saharan Africa are living with HIV (Kanku & Mash, 2011:570). In this study participants referred to teenagers between ages 13 and 19 years as being particularly prone to STIs and HIV infection.

Girls are more likely to be abused in foster care than boys (Sarri & Phillips, 2004), as illustrated below.

"There was a teenager who was orphaned and said that she was sexually abused by a foster parent and she wants to go and stay somewhere safe."

Most girls who are sexually abused in foster care report trauma-related challenges, and experience self-blame and feelings of betrayal (Postmus, 2013:202). Some of them run away from home and become exposed to prostitution and further sexual exploitation. Sadly, reports indicate that adolescents whose first sexual experience was coercive are more likely to become pregnant and also reported the pregnancy as undesired, while some contracted STIs and HIV (Hammer & Banegas, 2010:291; Mwinga, 2012:29; Nemutanzhela, 2007:38; Sethosa, 2007:11).

The Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (2006, Section 153) provides for perpetrators of child abuse to be removed from the home rather than ordering the removal of the child to alternative care. Unfortunately, this may never happen in situations where teenagers are afraid to share their unpleasant experiences with their mothers.

"… that she was afraid to tell her mother that she was pregnant because she was impregnated by her stepfather. She said that her mother would not believe her if she could tell her and might chase her out of the house."

Consistent with this finding is that the presence of a stepfather in the home puts girls at risk to be abused by the stepfather and other men (Mullen et al. cited by Putnam, 2003:271). Furniss (2013:23) points out that a 14-year-old-girl who had been sexually abused by her stepfather tried to tell her mother, who did not believe her. Furthermore, adolescent rapes are often intra-family and the perpetrators are sometimes the father, the stepfather or other relatives (Cherry & Dillon, 2014:181). Educators are also perpetrators of rape of school-going teenagers.

"One teenager said that she was made pregnant by a teacher who was threatening to fail her and not to go to another grade. She agreed to have sex with him in a classroom where there was no condom to use. She said she agreed because she wanted to pass."

Some teachers intimidate and use their power and authority to coerce learners to have sex with them. As such, vulnerable female learners in many South African schools are exposed to educators who misuse their position of authority to intimidate and sexually abuse them (Prinsloo, 2006:307).

It has been noted that some teachers and parents do feel pity for teenagers who are overtly misused and taken for granted by educators (Moliko, 2010:26). However, their sympathy and disapproval do not translate into action in order to curb this scourge of sexual abuse in schools. Instead, the teenagers' lives are disrupted, while the educators proceed with theirs unhindered.

● Barriers to access health facilities

The 1994 action plan of the International Conference on Population and Development emphasises the need to improve youth and adolescent sexual and reproductive health services. However, the study by Nkwanyana (2011:8) in Mandini, iLembe District in KwaZulu-Natal highlights the difficulties encountered by villagers regarding transportation and their inability to access towns and clinics. Another study conducted among health workers revealed that nurses are often reluctant to provide contraceptives to adolescent girls and frequently try to manipulate them into abstaining from sexual activities (Ahanonu, 2014:33; Macleod & Tracey, 2010:18; Rangiah, 2012:13). The participants indicated a number of barriers to healthcare facilities.

"Some teenagers said that they need friendly user clinics so that they can access contraceptives without been teased by health workers."

"One teenager said that she thought she became pregnant because she stopped going for family planning at the clinic. She said that health workers turned her away when she requested contraceptives."

"Some teenagers reported that they had a problem with some health workers who turned them away from health facilities when they required contraceptives."

Previously, health services were found to be not youth-friendly because healthcare providers often disregarded an adolescent's situation (Panday et al., 2009:88; Ratlabala, Makofane & Jali, 2007:30). The unavailability of youth-only clinics in Rarotonga (Cooks Islands) and the lack of confidentiality and privacy - including the lack of young persons employed at clinics - were identified as some of the barriers to the utilisation of health services (Eijk, 2007:25).

The findings also support the assertion by Macleod and Tracey (2010:18) that the attitudes of nurses at hospitals and other health centres ironically constitute a barrier to adolescents' access to contraceptives in South Africa. Twenty years after the advent of democracy in South Africa, one does not expect to find inaccessibility of health services, but that all patients would receive fair treatment from health workers, as enshrined in the Bill of Rights (Edwards, 2008:228).

THEME 2: ISSUES RAISED BY PREGNANT TEENAGERS IN GROUP SESSIONS

A group creates an environment where individuals can collectively influence one another by disclosing their experiences, providing advice and information on successful coping strategies, as well as giving feedback to others (Teater, 2014:244). The magnitude of the teenagers' challenges and their reactions to the situation vary. A range of issues pertaining to pregnant teenagers' concerns were reflected upon by the participants, as discussed below.

● Pregnant teenagers' views of risk factors

Immaturity, poor decision making and a desire to emulate friends were acknowledged by participants as factors that lead to teenage pregnancy.

"Group members pointed out that their inability to see the future and psychological immaturity put them at risk."

Pregnant teenagers' inability to foresee the consequences of their behaviour and their psychological immaturity put them at risk (Malahlela, 2012:16).

Prior to becoming pregnant some young girls reportedly became involved in risky behaviour such as consuming alcohol.

"One group member said, her boyfriend used to buy her lots of alcohol and they will go to all taverns around their area to have fun and she was addicted to alcohol. She feared to give birth to an abnormal child. She indicated that she quit drinking when she was 2 months pregnant."

Sarri and Phillips (2004:550) found that of the 99 pregnant/parenting teens in Wayne County, Michigan, 10% reported incidents of "binge" drinking two weeks prior the study, but most stopped consuming alcohol during pregnancy.

● Reactions of teenagers after discovering their pregnancy

Some teenagers may experience emotional turmoil after learning about their pregnancies.

"Most group members pointed out that fear was the first emotion they experienced."

"Members indicated that sadness, loneliness, disturbing sleep patterns and confusion of not knowing what to do about the pregnancy."

"And other children are suicidal."

Many teenage mothers expressed feelings of loneliness, fear and isolation, but the supportive environment of the group enabled them to discuss these feelings and realise that they were not alone (Smith, 2013:15). Some pregnant teenagers may show feelings of shame, embarrassment, humiliation and fear of losing the respect of their parents, peers and communities (Bhana, Morrell, Shefer & Ngabaza, 2010:873). On the other hand, because of a lack of coping skills, adolescents may regard suicide as the only way out of a painful situation (Capuzzi & Golden, 2013:42).

● Teenagers desire to keep their children

Pregnant teenagers were unwilling to consider abortion or adoption and decided to keep their children after birth. It has also been noted that the child support grant (CSG) has led to the reduction of adoption (Department of Social Development, SASSA & UNICEF, 2012:11).

"The majority of group members did not want to terminate nor give their babies for adoption to people they do not know."

The finding resonates with that of Smith (2013:18) that most teenagers described their experiences as both a positive transition into adulthood as well as physiological hardship which they had to contend with, and thus decided to keep their babies.

· Challenges of telling parents about the pregnancy

Despite a more liberal outlook, sexuality is still a complex subject which most families find difficult to discuss openly (Kanku & Mash, 2010:70). It is for this reason that most teenagers are traumatised, fearful and embarrassed, and find it problematic to tell parents about their pregnancy.

"Some members said they were afraid to tell their parents because they would be disappointed. They were also afraid that if rejected they would raise their children alone. They would have financial difficulties in supporting their babies."

"They experienced trauma, fear, shame and embarrassment of having to reveal an early pregnancy to family members, partners and peers."

Similar findings were reported by Sarri and Phillips (2004:537). It is evident that stigma and discrimination inhibit communication between pregnant teenagers and their parents and others who may offer support or professional assistance.

● Reaction of family members towards pregnant teenagers

Teenage pregnancy comes as a shock and disappointment to most parents, and some stop supporting their daughters (Nemutanzhela, 2007:15), as illustrated below.

"Most teenagers reported that their family members were not supportive because they have brought shame in the family."

"They said that they were rejected by people close to them as soon as they found out that they were pregnant."

Sometimes parents distance themselves from pregnant teenagers because they feel ashamed that the community will look down upon the family (Chigona & Chetty, 2008:271).

● Reactions of peers towards pregnant teenagers

The negative reactions of classmates and friends towards pregnant teenagers have an adverse impact on their social functioning.

"One group member said that, when she is in a classroom, classmates would not talk to her. They have deserted her."

It has been established that pregnant teenagers feel neglected, isolated and rejected by peers, friends and educators (Chauke, 2013:34; Weed, Nicholson & Farris, 2015:58). In certain instances they were abandoned by their boyfriends and were blamed by peers for the pregnancy (Julie, 2013:20).

● Discrimination, stigma and social exclusion

Some communities regard pregnant teenagers as careless as well as immoral, and most of all not fit to mix with non-parenting learners or other children within the community. They are treated as and referred to as "the other girls" (Chigona & Chetty, 2008:274). Discrimination and stigmatisation are a major challenge faced by pregnant teenagers, which may lead to isolation and suicidal ideations.

"Yes, when pregnant teenagers are discriminated against, some tend to isolate themselves. When in isolation they begin to have suicidal thoughts because there would be no one to share their problems with. They feel depressed, lonely and that affects their psychological and emotional wellbeing."

Similarly, social isolation and stigmatisation have been identified as major personal problems faced by pregnant teenagers (Bezuidenhout, 2004:27; Department of Social Development, 2011:24; Sibeko, 2012:21). Expelling pregnant and parenting learners from school will be a contravention of the South African Schools Act No. 84 of 1996 (SASA). In the event where schools do not expel pregnant and parenting learners, communities find ways of mocking teenage mothers on their way to or from school in an effort to prevent them from attending school. As a result, pregnant teenagers experience feelings of isolation and depression, which are detrimental to the quality of their lives.

Sarri and Phillips (2004:541) state that "[t]he correlates of adolescent female depression that have been noted in nearly all studies include: pregnancy, sex, stress and crises, low socio-economic status, absence of social support linked with abuse, eating disorders, and ineffective coping strategies." The participants shared the following:

"Group members also said that stigma during and after pregnancy lead them to depression, social exclusion, low self-esteem and poor academic performance such as grade repetition, temporary withdrawal from school, and dropping out of school."

"For instance, most pregnant teenagers in groups I have conducted said they were socially excluded. They pointed out that they wanted to be recognised in a family setting, as well as in society and need affection."

Depression is common among pregnant teenagers (Coelho, Pinheiro, Da Silva, Quevedo, Souza, De Matos, Castelli & Pinheiro, 2014:1241). Teenage pregnancy may affect the child's relationship with other family members, schoolmates and educators. Moreover, it is perceived to lower the school's reputation and that of the community at large (Runhare & Vandeyar, 2011:4110).

● Anger and thoughts of committing suicide among pregnant teenagers

Many men responsible for impregnating teenagers provide little or no support to the girls (Domenico & Jones, 2007a:7). As a result, depression sets in and has been found to be a risk factor for suicide among pregnant teenagers (Coelho et al., 2014:1241). Several researchers reported on the link between suicide and teenage pregnancy (Cherrington & Breheny, 2005:103). Hence, some pregnant teenagers who felt betrayed by their boyfriends contemplated suicide.

"The majority of group members pointed out that after being betrayed by the married men and boyfriends, who impregnated them, thought of committing suicide because there was no support system for them."

"Some members said that they were angry towards their boyfriends who disappointed them. They said that their boyfriends promised to marry them."

The findings are consistent with those from a study of 828 pregnant teenagers in Brazil, namely that suicidal behaviour is relatively common among pregnant teenagers (Pinheiro, Coelho, Da Silva, Quevedo, Souza, Castelli, De Matos & Pinheiro, 2012:522). Failure to prevent pregnancy, especially unwanted pregnancy, has also been associated with a greater risk of suicide (Mosetlhe, 2011:30).

● Challenges of raising a child alone

Teenage mothers are frequently unable to cope with raising children without support. Currently their families and the state are providing minimal financial support. The provisions of the Maintenance Act No. 22 of 2005 stipulate that the parents of teenage parents should contribute.

"Most members pointed out that they could not cope because raising a child alone was difficult and needs money. They were not working and therefore could not cope alone."

Lack of preparedness for motherhood may be frustrating for teenagers who were unaware of the financial demands of raising a child. This is also attributed to limited cognitive development, peer pressure or the need to emulate others.

● Poverty

Poverty is one of the challenges facing South African youths (Gouws et al., 2008:5). For instance, the lack of proper housing and privacy exposes children to parents' sexual activities (Bezuidenhout & Joubert, 2008:32) and this could lead to experimentation, which may result in pregnancy. The children of teenagers from poor backgrounds are likely to end up poor as well (Domenico & Jones, 2007a:8). Because of the low socioeconomic background of most parents, pregnant teenagers are likely to depend on the goodwill of their maternal relatives or public assistance for financial support. Access to services determines their utilisation and therefore pregnant teenagers need to know about eligibility, application procedures and location of the service. They therefore require information on the child support grant (CSG) offered by government to children.

"Most pregnant teenagers reported that they wanted to know how to apply for child support grant."

"Another group member indicated that most of them are from poor families, so they needed this grant to survive."

"All the areas that I serve are rural villages. Most families depend on grants."

The CSG is regarded as a successful intervention in reducing poverty and promoting human capital development (Department of Social Development, SASSA & UNICEF, 2012:11). IRIN News (2007) reported that some observers were of the view that the CSG was an incentive to young girls to fall pregnant, a view held by social workers as well (Nhedzi, 2013). However, this perspective was disregarded after the finding that "the increased uptake of the CSG is attributable to a growing awareness of its availability and active measures by government to promote uptake" and that it has reached 93% of poor children (Panday et al., 2009:57). Kanku and Mash (2010:569) also argue that there is no support for the belief that the child support grant encourages teenage pregnancy as there has been a decrease in the teenage fertility rate in South Africa over the same period.

● Inability to cope with school work

Participants in the study of Sarri and Phillips (2004:553) experienced health challenges such as anaemia, toxaemia and hypertension, while many did not seek prenatal care. Hence, balancing school work and pregnancy could become overwhelming, resulting in some teenagers dropping out of school.

"Another challenge that was discussed was difficulties in continuing with their studies. Members indicated that it is difficult to continue with education when pregnant because they get tired all the time. They feel sleepy."

The finding supports the view that the school performance of pregnant teenagers is often lower than that of their peers (Malahlela & Chireshe, 2013:7). The reasons include, among others, non-attendance as a result of problems caused by unplanned pregnancy and fatigue, particularly towards the end of the pregnancy.

"Group members indicated that they found it difficult to keep up with their peers where academic performance is concerned. One group member said she was told by the school to stay at home until she gave birth. Others said that they found school boring because they sleep in class and they were not allowed to eat in the classrooms."

The Constitution and current educational policy promote "education for all" which allows pregnant and parenting learners to continue their schooling. Several studies show the rates of school dropout as higher among pregnant teenagers compared to those who were not pregnant (Doğan-Ates & Carrión-Basham, 2007:555). Participants also mentioned that:

"In the entire support groups I have conducted, three pregnant teenagers had dropped-out of school."

"One teenager said that her school performance dropped and she was tired of being embarrassed by teachers and mocked by classmates."

Even though pregnant teenagers are permitted and encouraged to continue attending school, the negative attitudes of teachers and other learners may dissuade them from doing so.

● Pregnant teenagers' desires and aspirations

The aspirations of pregnant teenagers should be explored within their social contexts. Variables such as gender, family socioeconomic status, family support, parental expectations and cultural values influence teenagers' aspirations (Domenico & Jones, 2007b:24; Khallad, 2000:790). The participants mentioned that pregnant teenagers aspire to further their studies, but did not state their career choices.

"These teenagers indicated that they just wanted to stay in school. They said they have made mistakes and regret being pregnant. They were not prepared to become teenage mothers."

In their study Domenico and Jones (2007b:24) found that a large number of pregnant adolescents (13 to 19 years) aspired to become registered nurses. This was attributed to "their exposure to the nursing community throughout the duration of their pregnancy and birth process" (2007b:30). For the sake of posterity, it is critical to invest in human and social capital by prioritising children as citizen-workers of the future (Lister, 2003:431).

Sub-theme 2.1: Content of group work sessions

It is important to keep the group as small as possible so that members can connect with each other, and share their thoughts and feelings. Considering the issues raised by pregnant teenagers, the number of sessions conducted appeared to be inadequate, and this limited group members' exploration of concerns and challenges.

"I had a support group of 8 members, meeting once a week, on Wednesdays from 15h45 to 16h30. Sometimes we had 4 to 6 sessions."

Even though the list of topics below is not exhaustive, they were meant to help discover and build on the strengths of pregnant teenagers to bring about hope, self-reliance and personal satisfaction rather than focusing on problems (Kaplan & Berkman, 2016:65). Thus group sessions were empowering for teenagers.

"I assist group members to draw up a programme which entails topics such as parenting skills, prevention of secondary pregnancy, and how to apply for child support grant. The group goals will direct us to formulate the content of the group sessions."

"Members will prioritise their topics that they feel must be discussed such as how to manage emotions coping with stress problem solving and decision making. In that case the group members will determine the programme of the group."

"Group members determine the content of group sessions."

It is important to ensure that the content of the group sessions does not rely on what the group worker considers to be important, but on the real needs of the members (Nicholas et al., 2010:135; Teater, 2014:249; Zastrow, 2015:411).

Varied and relevant topics discussed in group sessions enabled pregnant teenagers to share experiences, receive new information, and accept and cope with their situations.

"The topics are about being stigmatised and discriminated against by family members, their peers, boyfriends as well as their teachers."

"Other challenges that were included in the programme were suicidal thoughts."

"I guide those who are suicidal and provide options for example adoption, abortion and/or fostering of the child."

"Let me start by explaining unemployment, because it was a priority topic for discussions."

The participants explained how considerable energy is devoted to developing cohesion and group functioning, and words such as performance and problem solving are frequently used to convey the emphasis on work and goal achievement (Nicholas et al., 2010:131; Teater, 2014:244; Toseland, Jones & Gellis, 2004:25).

THEME 3: INFORMATION AND SKILLS IMPARTED DURING GROUP SESSIONS

The participants indicated that the group sessions were guided by the strengths approach. This approach has been used to reduce symptoms of depression and increase the quality of life of group members (Kaplan & Berkman, 2016:65). The information provided during group sessions included aspects such as effective communication, the life cycle, HIV/AIDS and the importance of knowing one's status, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, how to apply for the CSG, adoption, and available community services such as spiritual support.

Skills highlighted during group sessions included life skills, communication skills, coping mechanisms, problem solving, creative thinking, self-awareness, recognition of one's strengths (using the strength perspective) and weaknesses, and how to handle emotions such as anger and sadness. Parenting skills were not mentioned despite the teenagers' expressed fears of raising a child. The Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (2006: Chapter 8) requires social workers to develop appropriate parenting skills programmes to prevent child abuse and neglect, and to protect families from the risk of disintegration. Based on their knowledge and skills, social workers performed a variety of roles relevant to the needs of pregnant teenagers such as acting as an enabler, broker, advocator, educator, negotiator, mediator and activist (Zastrow, 2010:44). In addition, participants played the role of advisor, case change agent, catalyst, case manager, information provider and motivator.

DISCUSSION

This study has shed light on the reflections of social workers relating to the causes of teenage pregnancy and pertinent issues raised during the support group sessions. Understanding the Personal, familial, social and economic factors contributing to the prevalence of teenage pregnancy help professionals address these challenges. The reality of being pregnant seems to dawn on teenagers only after they are rejected by parents, boyfriends, friends and peers; this leaves some depressed, isolated and contemplating suicide.

During assessment the social worker together with the teenager makes a determination of a beneficial intervention plan. Group work is essential for pregnant teenagers as they are able to connect with others in a similar situation, and are reassured that they are not alone. Furthermore, it offers mutual aid to those grappling with feelings of sadness, contemplating suicide, fear and frustration, especially if their boyfriends have deserted them.

The strengths approach is also ideal for pregnant teenager support groups as it focuses on helping them to identify and rely on their strengths, and to improve their social functioning and wellbeing. This approach is also appropriate as it helps in recognising their resilience and affirming their strengths. The violation of the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005 (Section 111) by older men and educators who molest teenagers sexually should be challenged as it is an indictment on society that it is unable to protect their children against perpetrators.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The complexity of teenage pregnancy calls for a coordinated collaboration among various welfare, educational and health organisations to successfully prevent teenage pregnancy. Hence, an understanding of the factors associated with teenage pregnancy and its consequences is necessary to effectively mitigate the consequences of adolescent pregnancy (Domenico & Jones, 2007:6). Therefore, networking with relevant stakeholders, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), faith-based organisations (FBOs) and private institutions can play a crucial part in preventing repeat pregnancies among teenagers.

Social workers should continue marketing their services.

"I think we must have a way of marketing our services because people, particularly teenagers, think that social workers' job is only doing foster care grant and resolving family conflicts."

This aspect is crucial as nothing in the South African literature on adolescent or teenage pregnancy from the health sector recognises or acknowledges social work.

Moreover, the authors support Sarri and Phillips's (2004:557) suggestion that "[a] more viable and long-term solution for agencies may be to use group work approaches to build greater support and solidarity among at-risk young women. The model developed by Alternatives for Girls is built on this strategy along with peer leadership education and has been effective".

Formal social support and informal support should be offered to pregnant teenagers (Motjelebe, 2009:22) and those who leave school as a result of their pregnancy. To address the age divide, young persons who may serve as role models should be involved as teenagers find it easier to relate to their peers. Social workers should also strive to promote gender equality and the empowerment of young women at all levels of intervention. This should be done alongside health workers who will focus on providing reproductive health information and services. Such an effort would address teenagers' concerns regarding barriers to accessing health facilities.

There is a need for the provision of competent supervision of social workers to meet the demand for effective services (Crosson-Tower, 2009:242). On the other hand, Kemp (2013) questions pertinent issues regarding school social work in South Africa, including the non-existence of a national policy, guidelines regarding the appointment of or practice standards for school social workers at national or provincial level, and no provision whatsoever for school social workers in some provinces.

To uphold the principles of social justice, human rights and collective responsibility which are central to social work (International Federation of Social Workers, 2014) different social work associations, including the Association of South African Schools of Social Work Institutions (ASASWEI) and the South African Council on Social Service Professions (SACSSP), should make an unequivocal commitment to serve as pressure groups to the Department of Justice for the enforcement of the Maintenance Act No. 22 of 2005. Silence and complacency on the part of these groups would be hypocritical, since they have committed themselves to be the voice of the voiceless and vulnerable groups.

CONCLUSION

Progress in reducing the escalating rate of teenage pregnancies will not be accomplished unless fathers, young and old, are forced to take responsibility for their children. Failure to do so is tantamount to the erosion of the family values that fathers should care, protect and provide for their children. Currently, maternal grandparents and taxpayers are bearing the burden of providing for children with absent fathers. Unfortunately, this strategy is not ideal or sustainable in the long term.

REFERENCES

AHANONU, E.L. 2014. Attitudes of healthcare providers towards providing contraceptives for unmarried adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Journal of Family and Reproductive Health, 8(1):33-40. [ Links ]

BENARD. B. & TRUEBRIDGE, S. 2013. Resilience begins with beliefs: building on student strength for success in schools. London: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

BEZUIDENHOUT, F.J. 2004. A reader on selected social issues (3rd ed). Pretoria, Hatfield: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

BEZUIDENHOUT, C. & JOUBERT, S. 2008. Child and youth misbehavior in South Africa. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

BHANA, D., MORRELL, R., NGABAZA, S. & SHEFER, T. 2010. South African teachers' responses to teenage pregnancy and teenage mothers in schools. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(8):871-883. [ Links ]

BRAUN, V. & CLARKE, V. 2013. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. United States of America: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

CAPRICORN DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK. 2007. [Online] Available: http://www.polokwane.gov.za [Accessed: 10/07/2015]. [ Links ]

CAPUZZI, D. & GOLDEN, L. 2013. Preventing adolescent suicide. United State of America: Accelerated Development INC. Publishers. [ Links ]

CHAUKE, H. 2013. The challenges experienced by teenage mothers in secondary school: the case of Hlanganani South Circuit. Polokwane: University of Limpopo. (M Education dissertation) [ Links ]

CHERRINGTON, J. & BREHENY, M. 2005. Politicizing dominant discursive constructions about teenage pregnancy: re-locating the subject as social. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 9(1):89-111. [ Links ]

CHERRY, A.L. & DILLON, M.E. 2014. International handbook of adolescent pregnancy: medical, psychosocial and public health responses. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [ Links ]

CHIGONA, A. & CHETTY, R. 2008. Teen mothers and schooling: lacunae and challenges. South African Journal of Education, 28(2):1-14. [ Links ]

CHILDREN'S ACT NO. 38 OF 2005. 2006. Government Gazette, 492(28944), June 19. Pretoria: South Africa. 1-217. [ Links ]

COELHO, F.M.D., PINHEIRO, R.T., SILVA, R.A., QUEVEDO. L.A, SOUZA, L.D.M., DE MATOS, M.B., CASTELLI, R.D. & PINHEIRO, K.A.T. 2014. Parental bonding and suicidality in pregnant teenagers: a population-based study in southern Brazil. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(8):1241-1248. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2009. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

CROSSON-TOWER, C. 2009. Exploring child welfare: a practice perspective (5th ed). Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION. 2010. Report on the annual school survey. [Online] Available: http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=126663 [Accessed: 08/09/2011]. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD), SASSA & UNICEF. 2012. The South African child support grant impact assessment: evidence from a survey of children adolescents and their households. Pretoria: UNICEF South Africa. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2011. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy in Limpopo Province. Polokwane: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DOEL, M. 2000. Groupwork. In: DAVIES, M. (ed), The Blackwell encyclopedia of social work. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

DOĞAN-ATES, A. & CARRIÓN-BASHAM, C.Y. 2007. Teenage pregnancy among Latinas. Examining risk and protective factors. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 29(4):554-569. [ Links ]

DOMENICO, D.M. & JONES, K.H. 2007a. Adolescent pregnancy in America: causes and responses. The Journal for Vocational Special Needs Education, 30(1):4-12. [ Links ]

DOMENICO, D.M. & JONES, K.H. 2007b. Career aspirations of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 25(1):24-33. [ Links ]

DOYLE, S. 2013. Reflexivity and the capacity to think. Qualitative Health Research, 23(2):238-255. [ Links ]

DRUMM, K. 2006. The essential power of group work: social work with groups. The Haworth Press, 29(2):17-31. [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J009v29n02_02 [ Links ]

EDWARDS, M. 2008. The informed practice nurse (2nd ed). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [ Links ]

EIJK, R. T. 2007. Factors contributing to teenage pregnancies in Rarotonga, Cook Islands. Ministry of Health United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). [ Links ]

FLISHER, A.J. & GEVERS, A. 2010. Mental health and risk behaviour. In: KIBEL, M., LAKE L., PENDLEBURY, S. & SMITH, C. (eds), South African Child Gauge 2009/2010. University of Cape Town: Children's Institute, 53-57. [ Links ]

FURNISS, T. 2013. The multiprofessional handbook of child sexual abuse: integrated management therapy and legal intervention. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

GENOBAGA, J. 2004. Teenage girl!: what I want to know without asking. Australia: Signs publishing company. [ Links ]

GOUWS E., KRUGER, N. & BURGER, S. 2008. The adolescent. Johannesburg: Heinemann Publishers (Pty) Ltd. [ Links ]

HAMMER, J. & BANEGAS, M.P. 2010. Knowledge and information seeking behaviours of Spanish-speaking immigrant adolescents in Curacao, Netherlands Antilles, family and community health. The Journal of Health Promotion and Maintenance, 33(4):285-300. [ Links ]

HOCHFELD, T. 2002. Striving for synergy: gender analysis and indigenous social work practice in South Africa. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 38(2):105-118. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS, 2014. Global definition of social work. [Online] Available: ifsw.org/policies/definition-of-social-work/ [Accessed: 05/07/2016]. Accessed: 08/08/2008]. [ Links ]

IRIN NEWS. 2007. South Africa: teenage pregnancy figures causes alarm. [Online] Available: http://www.irinnews.org/news/2007/03/06/teenage-pregnancy-figures-cause-alarm [Accessed: 08/07/2013]. [ Links ]

JULIE, V.J. 2013. Young mothers' perceptions of teenage pregnancy in Vredendal: a social cognitive learning approach. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Social Work dissertation) [ Links ]

KANKU, T. & MASH, R. 2010. Attitudes, perceptions and understanding amongst teenagers regarding teenage pregnancy, sexuality and contraception in Taung. South African Family Practice, 52(6):563-572. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, D. & BERKMAN, B. 2016. The Oxford handbook of social work in health and aging (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

KARRA, M. & LEE, M. 2012. Human capital consequences of teenage childbearing. In: KAUFMAN, C.E., DE WET, T. & STADLER, J. 2001. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 32(2):147-160. [ Links ]

KEMP, M. 2013. School social work addressing the social barriers to learning and development in order to ensure educational achievement. [Online] Available: www.naswsa.co.za/conference2013/presentations/25%20September%202013%20-%20M% [Accessed: 27/07/2014]. [ Links ]

KHALLAD, Y. 2000. Education and career aspirations of Palestinian and U.S. youth. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(6):789-791. [ Links ]

KHUNOU, G., PILLAY, R. & NETHONONDA, A. 2012. Social work students' perceptions of gender as a career choice determinant. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 24(1):120-135. [ Links ]

KIM, C. 2008. Teen sex: the parent factor. [Online] Available: http://www.hertage.org/research/reports/2008/10/teen-sex-the-parent-factor [Accessed: 07/10/2013]. [ Links ]

KYEI, K.A. 2012. Teenage fertility in Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, how high is that? Scholar Link Research Institute Journals, 3(2):134-140. [ Links ]

LIMPOPO PROVINCIAL POPULATION AND DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE. 2012. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy in Limpopo Province. [Online] Available: www.dhsd.limpopo.gov.za [Accessed: 01/07/2016]. [ Links ]

LINDSAY, T. & ORTON, S. 2012. Groupwork practice in social work (Transforming social work practice series) (2nd ed). Cathedral Yard: Learning Matters Ltd. [ Links ]

LISTER, R. 2003. Investing in the citizen-workers of the future: transforming in citizenship and the State under new labour. Social Policy & Administration, 37(5):428-443. [ Links ]

LUKE, N. 2005. Confronting the 'sugar daddy' stereotype: age and economic asymmetries and risky sexual behavior in urban Kenya. International Family Planning Perspective, 31(1):6-14. [ Links ]

LYON, M.E. & D'ANGELO, L.J. 2006. Teenagers, HIV and AIDS: insights from youth living with the virus. Westport, Conn: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

MACLEOD, C.I. & TRACEY, T. 2010. A decade later: follow-up review of South African research on the consequences of and contributory factors in teen-aged pregnancy. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(1):18-31. [ Links ]

MAINTENANCE ACT NO. 22 OF 2005. Government Gazette. Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

MAKIWANE, M. 2010. The child support grant and teenage childbearing in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 27(2):193-204. [ Links ]

MAKOAE, M., ROBERTS, H. & WARD, C.L. 2012. Child maltreatment prevention readiness assessment: South Africa. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

MAKOLA, M.P. 2011. Teenage pregnancy: views of parents/caregivers, teenagers and teachers at two high schools in Soweto, Gauteng. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. (M Psychology dissertation) [ Links ]

MALAHLELA, M.K. & CHIRESHE, R. 2013. Educators' perceptions of the effects of teenage pregnancy on the behaviour of the learners in South African secondary schools: implications for teacher training. Journal of Social Sciences, 37(2):137-148. [ Links ]

MALAHLELA, M.K. 2012. The effects of teenage pregnancy on the behaviour of learners at secondary schools in the Mankweng, Limpopo. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Education dissertation) [ Links ]

MATLALA, S.F., NOLTE, A.G.W. & TEMANE, M.A. 2014. The need for a model to facilitate health for pregnant learners attending secondary schools in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Science, 5(25):83-90. [ Links ]

MEADE, C.S. & ICKOVICS, J.R. 2005. Systematic review of sexual risk among pregnant and mothering teens in the USA: pregnancy as an opportunity for integrated prevention of STD and repeat pregnancy. Social Science & Medicine, 60:661-678. [ Links ]

MILLER, B.C., BENSON, B. & GALBRAITH, K.A. 2001. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: a synthesis. Development Review, 21:1-38. [ Links ]

MNYIPIKA, N. 2014. Exploring factors that influence condom use among high school teenagers aged between 16 and 18 years in Dutywa District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Sociology dissertation) [ Links ]

MOLIKO, M.R. 2010. Teachers' perceptions of teenage pregnancy in selected schools in Lesotho. Durban: University of Zululand. (M Education dissertation) [ Links ]

MOSETLHE, T.C. 2011. The occurrence of parasuicide among pregnant women at Dr George Mukhari Hospital: a retrospective study. Polokwane: University of Limpopo-Medunsa Campus. (M Medicine dissertation) [ Links ]

MOTHIBA, T.M. & MAPUTLE, M.S. 2012. Factors contributing to teenage pregnancy in the Capricorn district of Limpopo Province. Curationis, 35(1):1-8. [ Links ]

MOTJELEBE, N.J. 2009. The social support network of teenage mothers in Botshabelo. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. (MA (SW) dissertation) [ Links ]

MPANZA, N.D. & NZIMA, D.R. 2010. Attitudes of educators towards teenage pregnancy. Procedural Social and Behavioural Sciences, 5:431-439. [ Links ]

MWINGA, A.M. 2012. Factors contributing to unsafe sex among teenagers in the secondary school of Botswana. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Public Health dissertation) [ Links ]

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS. 2009. An author's guide to social work journals (5th ed). Washington, DC: NASW Press. [ Links ]

NDUVHENI, S. 2011. Limpopo MECs to address teenage pregnancy. [Online] Available: http://www.sanews.gov.za [Accessed: 20/03/2013]. [ Links ]

NEMUTANZHELA, T.S. 2007. Traumatic experiences of teenage pregnancy by married men: a challenge to pastoral care. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (M Theology dissertation) [ Links ]

NHEDZI, F. 2014. The experiences and perceptions of social workers on the provision of family preservation services in the Ekurhuleng Metropolitan, Gauteng Province. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Social Work dissertation) [ Links ]

NICHOLAS, L., RAUTENBACH, J. & MAISTRY, M. 2010. Introduction to social work. Cape Town: Juta & Company Ltd. [ Links ]

NKWANYANA. T.R. 2011. A study of the high rate of teenage pregnancy in high schools in the iLembe District. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (M Psychology of Education) [ Links ]

OMAR, K., HASIM S., MUHAMMAD N.A., JAFFAR, A., HASHIM, S.M. & SIRAJ H.H. 2010. Adolescent pregnancy outcomes and risk factors in Malaysia. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 111(3):220-223. [ Links ]

PANDAY, S., MAKIWANE, M., RANCHOD, C. & LETSOALO, T. 2009. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa - with a specific focus on school-going learners. Child, Youth, Family and Social Development, Human Sciences Research Council. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

PINHEIRO, R.T., COELHO, F.M.D., DA SILVA, R.A., QUEVEDO, L.D., LUCIANO DIAS DE MATTOS SOUZA, L.D.D., CASTELLI, R.D., DE MATOS, M.B. & PINHEIRO, K.A.T. 2012. Suicidal behavior in pregnant teenagers in southern Brazil: Social, obstetric and psychiatric correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136:520-525. [ Links ]

POSTMUS, J.L. 2013. Sexual violence and abuse: an encyclopaedia of prevention, impacts and recovery. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. [ Links ]

PRINSLOO, S. 2006. Sexual harassment and violence in South African schools. South African Journal of Education, 26(2):305-318. [ Links ]

PUTNAM, F.W. 2003. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. Research update review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent. Psychiatry, 42(3):269-278. [ Links ]

RADEBE, N. 2013. The scourge of teen pregnancies. [Online] Available: http://www.sanews.gov.za [Accessed: 15/03/2013]. [ Links ]

RANGIAH, J. 2012. The experiences of pregnant teenagers about their pregnancy. Cape Town: Stellenbosch University. (M Nursing Science dissertation) [ Links ]

RATLABALA, M.E., MAKOFANE, M.D.M. & JALI, M.N. 2007. Perceptions of adolescents in low-resourced areas towards pregnancy and the choice on termination of pregnancy (CTOP). Curationis, Journal of the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa, 30(1):26-31. [ Links ]

RUNHARE, T. & VANDEYAR, S. 2011. Loss of learning space within a legally inclusive education system: institutional responsiveness to mainstreaming of pregnant learners in formal education. Gender & Behaviour, 9(2):4100-4124. [ Links ]

SARRI, R. & PHILLIPS, A. 2004. Health and social services for pregnant and parenting high-risk teens. Children and Youth Services Review, 26:537-560. [ Links ]

SAYEGH, M.A., CASTRUCCI, B.C. LEWIS, L. & HOBBS-LOPEZ, A. 2010. Teen pregnancy in Texas: 2005 to 2015. Springer: Maternal Child Health. [ Links ]

SETHOSA, G.S. 2007. Teenage pregnancies as a management issue in township schools in George. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. (M Education dissertation) [ Links ]

SHEAFOR, B.W. & HOREJSI, C.R. 2012. Techniques and guidelines for social work practice (9th ed). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SIBEKO, P.G. 2012. The effect of pregnancy on a schoolgirl's education. Durban: University of Zululand. (M Educational Psychology dissertation) [ Links ]

SMITH, N. 2013. Teenage pregnancy: an exploration of teenage mothers' perceptions and experiences of support from eco-system framework. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand. (M Education dissertation) [ Links ]

SODI, E.E. 2009. Psychological impact of teenage pregnancy on pregnant teenagers. Polokwane: University of Limpopo. (M Psychology dissertation) [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOLS ACT NO. 84 1996. Government Gazette No. 17579. SOUTH AFRICA. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA, 2014. General Household Survey. Pretoria: National Library of South Africa. [ Links ]

SWART, H. 2012. A broken system cannot fix the broken people. Mail and Guardian, June 28:24. [ Links ]

TEATER, B. 2014. An Introduction to applying social work theories and methods (2nd ed). Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Open University Press. [ Links ]

TOSELAND, R.W. & RIVAS, R.F. 2012. An introduction to group work practice (7th ed). Boston: MA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

TOSELAND, R.W., JONES, L.V. & GELLIS, Z.D. 2004. Group dynamics. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

UNFPA. 2002. Indicator: Births per 1000 women (15-19 yrs) - 2002 UNFPA, State of World Population. [Online] Available: http://globalis.gvu.unu.edu/indicator.cfm?country=GB&IndicatorID=127 [Accessed: 22/06/2013]. [ Links ]

WEED, K., NICHOLSON, J.S. & FARRIS, J.R. 2015. Teen pregnancy and parenting: rethinking the myths and misperceptions. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

ZASTROW, C.H. 2015. Empowerment series: social work with groups: a comprehensive work text (9th ed). Belmont: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

1 To reserve anonymity the areas in which the participants operate have been omitted.