Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.53 n.1 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-547

ARTICLES

The voice of the child: experiences of children, in middle childhood, regarding children's court procedures

Mrs Louie Talitha ClaasenI; Prof Gloudina Maria SpiesII

IPostgraduate student at University of Pretoria, Lecturer at UNISA. Louie Claasen <louieclaasen@gmail.com>

IIDepartment of Social Work and Criminology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. gloudien.spies@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Current statistics show an alarming number of children entering the South African children's court system annually. Yet little to no research has been conducted directly with the children who actually attend children's courts within the South African context, specifically since the promulgation of the new Children's Act 38 of 2005. The research reported here, using one -on-one semi-structured interviews, highlighted the voices of the children regarding their experiences of children's court procedures. Results indicated that, because of a lack of preparation, the majority of children experienced children's court procedures negatively. Recommendations for a children's court-specific preparation programme are made.

INTRODUCTION

By mid-2015 the number of children living in South Africa was in excess of 21.5 million (21 736 416) (Statistics South Africa, 2015). This constitutes nearly 40% of South Africa's population, which at that stage had reached close to 55 million (54 956 900) (Statistics South Africa, 2015). Over seven million children are living in poverty (Hall, 2012a; South African Human Rights Commission/UNICEF, 2011a), and of the 16.56 million beneficiaries of social grants in South Africa, 74% (more than 12 million) are children (Hall, 2012a; UNICEF, 2015). In the Children's Act 38 of 2005 a child is defined as "a person under the age of 18" (Children's Act 38 of 2005:12).

The number of children's court cases opened during 2013/2014 totalled 76 799 (Department of Justice, 2014). Of these cases, 66 289 were finalised and 70 220 children were found to be in need of care and protection (Department of Justice, 2014). In the researcher's opinion, such high numbers are a cause for concern. Between 2005 and 2012 over half a million (613 000) children were placed in foster care and received foster care grants (South African Human Rights Commission/UNICEF, 2011b). This figure excludes those children who were involved in other matters heard in children's courts such as, but not limited to, matters relating to the health of a child, contribution orders, child in need of care and protection, and adoption within this time period (Hall, 2012; Hall 2012b; Meintjes & Hall, 2010; National Budget Review, 2013). These statistics highlight the dire reality children in South Africa are facing, and create the basis for the focus of this study, which were the experiences of children during children's court procedures.

From the above figures it is evident that a significant number of children enter the children's court system every year and, based on the researcher's professional experience in these courts, each child experiences children's court procedures differently, with consequently varied levels of distress. At the heart of the above understanding is ensuring that the best interests of the child are upheld as well as protecting each child's right to participate effectively during the entire process. It thus becomes crucial to understand if children's rights are safeguarded within the children's court procedures, and if so how are they safeguarded.

Although a vast amount of research has been done on children's experiences during divorce or criminal court proceedings, there is a serious lack of research and literature on anything related to children's courts, specifically since the promulgation of the Children's Act 38 of 2005 in 2010. Consequently, the focus in this article will be on the findings of a study conducted by Strydom (2013), which highlighted the experiences of children regarding children's court procedures, including the involvement and shortcomings of various role-players. This research was conducted qualitatively, using one-on-one semi-structured interviews with children between the ages of eight and 12.

This article begins with a contextualisation of children in children's court. The following section discusses the various relevant legislation and policies as well as the practical implementation and implications of said legislation and policies. This is followed by an outline of the research methodology used in the study, a presentation of the findings and the conclusions of the study. Lastly, recommendations are made for the improvement of children's experiences of children's court procedures.

LEGISLATION, POLICIES AND PRACTICE

South Africa has shown great progress in recognising the rights of children (Rosa & Dutschke, 2006). Various achievements include: the adoption of a child-sensitive constitution; the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, henceforth referred to as UNCRC, in 1994; the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (henceforth referred to as the African Charter), in 2000; and the promulgation of the Children's Act 38 of 2005 in April 2010 (Ratification Table: African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2013; Africa, Dawes et al. 2003; Matthias & Zaal, 2010; Rosa & Dutschke, 2006).

A discussion on the various relevant sections of all of the above-mentioned legislation and policies follows.

Section 16(b) of the Bill of Rights, section 32(1) of the South African Constitution as well as Section 10 of the Children's Act 38 of 2005, Article 12 and 13 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and Article 7 of the African Charter all recognise the rights of children to receive legal information that is age-appropriate as well as to express their views on anything that affects them (African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2009; Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 16th amendment, Act 1 of 2009; Children's Act 38 of 2005; UNICEF, n.d.). Accordingly, in section 9 of the SA Constitution, the rights mentioned above are rights without discrimination of any kind, including age discrimination (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 16th amendment, Act 1 of 2009).

Furthermore providing age-appropriate information has a definite bearing on the various procedures in and around children's court and can include providing information about:

• children's court procedures, i.e. what the child can expect from proceedings, and the court's responsibility to act in the best interests of the child;

• the rights, roles and responsibilities of all parties involved in the court proceedings, specifically those concerning the child;

• children's rights to express their views and preferences regarding any decision made in terms of children's court procedures;

• the potential consequences of children expressing their preferences; and

• the fact that children's views and preferences are not deciding factors and the court is not bound by the preference of the child, specifically when the child's best interests seemingly lie elsewhere (Mahlobogwane, 2010; Taylor, Tapp & Henaghan, 2007).

Furthermore, Section 28(2) of the Bill of Rights, the Children's Act 38 of 2005 as well as Article 4 of both the UNCRC and the African Charter all emphasise a child's best interests as being of paramount and primary importance.

The central role of children's rights in South African legislation and policies as highlighted above are relatively new and constitute a definite shift in how children are viewed, as well as their place in society. In short, in terms of the law children are no longer viewed as passive victims of parental and adult disputes, but rather children are now active rights-holders (Bainham & Gilmore, 2013; Diduck, 2003; Heaton, 2012; Kaganas & Diduck, 2004; Nathanson & Saywitz, 2015). Thus children are acknowledged as autonomous individuals who have the right to information and participation in all aspects that significantly affect them (Children's Act 38 of 2005; James, 2003).

However, despite the evident advancements in legislation and policies regarding children's rights, it appears that the implementation of these rights does not occur at the same pace as the development of the legislation and policies. This is evident in that, despite children's rights being a central focus in the current legislation and policies, judgments are often made during children's court proceedings as to whether or not children's wishes and views regarding their future are really in their own best interests or not (Bilson & White, 2005). Furthermore, Bilson and White (2005:236) found that in court settings, "the views of children are generally a secondary consideration to adult views of their best interests."

There are a number of views on the implementation of legislation and policies, especially when it comes to preserving the rights and best interests of the child. In this regard, when determining a child's best interests, several authors (Barrie, 2011; Erasmus, 2010; Heaton, 2009) suggest that a more individualised, contextualised and child-centred approach should be employed when interacting with and assessing children during the court process. In this way, the possibility of a child's best interests being manipulated by a powerful and potentially subjective adult can be minimised (Heaton, 2009). Likewise, adhering to this process will ensure that the child's rights are more fully realised (Bilson & White, 2005).

In research conducted amongst professionals involved in children's court proceedings Zaal (2003) found that often even well-intentioned lawyers and social workers presuppose that it is more important to inform the court of what they believe to be in the child's best interests than effectively assisting the child to express his or her views in person. Bilson and White (2005) and Sheehan (2003) confirm this finding by noting that the legal process often revolves around the participating adults' views regarding the child's best interests. Consequently, professionals involved in children's court proceedings should be sensitive towards the rights of children as well as possess and be able to impart specialist knowledge in order to ensure that children's rights are respected and upheld during such proceedings (Prinsloo, 2008). Of particular interest here, Africa Dawes, Swartz, & Brandt, (2003) note that in a traumatic situation - resulting in court proceedings and often not of a child's making - the proper way to serve the best interests of the child is to ensure that the child's rights form the focal point of the decision-making process.

Various authors advocate the need to allow children to express their views and preferences (Bala, Talwar & Harris, 2005; Barratt, 2003; Fortin, 2009; Mahlobogwane, 2010; Parkinson, 2006; Smart, Neale & Wade, 2001; Wade Smart, 2002). The researcher highlights two main motivations for allowing the expression of views and preferences of a child. Firstly, children are remarkably perceptive as to what happens around them. As such, they are able to provide a unique perspective on their situation which, combined with other factors, may assist the court to arrive at a decision (Bala et al., 2005; Barratt, 2003; Fortin, 2009; Mahlobogwane, 2010; Parkinson, 2006; Smart et al., 2001; Wade & Smart, 2002). Secondly, decisions made regarding a child's future can have significant repercussions for the child concerned. After all, the child will have to live with the court's decision, a decision which could have a perpetuating negative effect even into adulthood (Barratt, 2003; Lefevre, 2010 & Mahlobogwane, 2010).

In practice professionals will often base their perceptions of a child on the child's ability to participate in the decision-making process, irrespective of what that process may involve (Leeson, 2007). However, children often do not use formal verbal communication to the same degree as adults do, but rather convey their feelings, intentions and experiences through play, metaphor, body language and other behaviours (Lefevre, 2010). In effect, when children, especially younger children, are asked to participate solely by means of formal language, they are not afforded the opportunity to display their full competence and, consequently, could be viewed as incompetent (Thomas & O'Kane, 2000). This highlights why a more flexible and tolerant approach ought to be followed when communicating and interacting with children.

With reference to children's ability to provide information, Taylor, Tapp & Henaghan (quoted in Taylor et al., 2007:69), state:

"Research evidence shows that all children, whatever their age, are generally able to express what is important to them. This is particularly so when the emphasis shifts from the child's ability to provide information to the adult's competence to elicit, or to observe, it. ... Furthermore, the skill of the adult engaged in ascertaining the child's views, rather than the child's level of cognitive development, plays a central role in the quality of the information elicited."

In terms of the above, Nathanson and Saywitz (2015), Davey, Burke and Shaw (2010), Mitchell (2006) and Prilleltensky, Nelson and Peirson (2001) acknowledge the still growing realisation of the importance of children being allowed to contribute to decisions regarding their future.

Furthermore, as a result of the adversarial adult nature of even children's court proceedings, it seems logical that children may struggle to communicate clearly (Mahlobogwane, 2010; McCoy & Keen, 2009). A resultant drawback of asking children to participate in this arena, which is often inconsistent with their level of development, is that children then appear incompetent. Following the logic of the above quote, this incompetence is not the result of children being incapable of providing good testimony, but rather a consequence of the adult's inability to ask questions in a manner appropriate to the child's level of development and the adult's inability to interpret children's responses correctly. This lack of ability is often the result of adults' lack of knowledge about levels of child development and the corresponding differences in language competence (McCoy & Keen, 2009; Saywitz, Jaenicke & Camparo, 1990). Consequently, the responsibility should not rest with the children to prove their maturity or ability to participate, but rather the responsibility should rest with the adults involved to listen, understand, support and provide appropriate guidance and assistance to the child. This could ensure that children's views are correctly conveyed and respected, thus empowering the child (Taylor et al., 2007).

In summary, so much of who children are - their behaviour, personality, self-knowledge; their cognitive processes such as thinking, understanding and verbal and non-verbal expression; emotional understanding and expression; and social understanding and interaction - is inextricably linked to each child's unique developmental circumstances (Berk, 2013; Louw & Louw, 2014; Santrock, 2006). As such, these circumstances and their invariable influence on the child's development and ability to participate should also be taken into consideration when working with children within the context of the children's court. Only when this is done can children effectively participate in procedures, some of which could have a lasting effect on their future.

The literature discussed above provides the basis from which this research study was conducted. A description of the research methodology utilised for the study follows.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research was an exploratory and descriptive study that utilised a qualitative approach (Creswell, 2013). The study utilised a collective case study design and focused on the exploration and description of current, real-life issues in order to create a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the children's experiences of children's court procedures (Creswell, 2013; Fouché & Schurink, 2011; Neuman, 2011). The population of this study comprised all children whose case files are with the South African Women's Federation (SAVF) and who had been exposed to children's court procedures. Purposive sampling was used to select child participants who were knowledgeable about children's court procedures (Neuman, 2011). The criteria used to select participants included non-gender-specific children who: had been exposed to children's court proceedings, from opening to finalisation; were between the ages of eight and 11; were fluent in English or Afrikaans; and who had attended children's court more than once, with the added proviso that their children's court proceedings had been finalised.

Because of these very specific criteria, finding participants within the limits of the study was challenging; however, data saturation was reached during the last three participants interviewed. As noted by Strydom and Delport (2011:391), data saturation occurs when data begin to repeat and little or no new information surfaces.

The sample was comprised of nine white participants between the ages of eight and 12 years, five males and four females. Socio-economic status was not a criterion for this study. Because of the criteria used for the purposive sampling, as well as the geographical areas in which the SAVF has offices where the researcher could conduct the interviews, it was very challenging to find participants. Consequently, the only participants who met all the criteria were white.

Because of the age of the children 8-12 years, and the sensitive nature of the content explored, questionnaires were not feasible. Therefore data were collected using semi-structured one-on-one interviews from the sample of nine child participants (Greeff, 2011). The interviews were transcribed and Creswell's spiral process was used to interpret and analyse the data in order to identify themes (Creswell, 2013). Since this study included children who had most probably experienced some form of neglect or abuse, due consideration was given to all relevant ethical aspects, namely avoidance of harm, voluntary participation and informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity, as well as debriefing (Strydom, 2011).

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The study provided important perspectives from child participants with regard to their experiences of children's court procedures. In the course of data analysis seven main themes emerged; however, for the purposes of this article, only the five most prevalent themes are discussed below:

• Interaction and participation with social worker;

• Preparation for children's court;

• First appearance in court and subsequent proceedings;

• Finalisation of proceedings; and

• Child's response to physical structure of children's court.

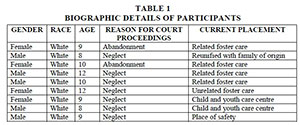

Biographical details of the participants

Of the nine participants who took part in this study, four were females and five were males between the ages of eight and 12 years. Two participants were involved in children's court proceedings as a result of abandonment and the other seven participants had been neglected because of parental substance abuse and, in two cases, domestic violence. Four participants were placed in related foster care, one in unrelated foster care, two in a child and youth care centre, and one had been reunified with the family of origin. A summary of the biographical profile can be found in Table 1 below:

Theme 1: Interaction and participation with social worker

Social workers become involved in matters that relate to the protection and daily care of children. This included matters that ranged from determining the paternity of a child to matters of child neglect, abuse and abandonment (Children's Act 38 of 2005). Involvement dictates the need for interaction and it would follow that in any professional relationship mutual communication is required (Lefevre, 2010). Part of this communication would be an explanation regarding the involvement of various parties, including the social worker.

When participants in this study were asked whether they understood the reason for the social worker's involvement in the situation they reacted as follows: five participants indicated that they did not understand why the social worker was involved in their family situation and two responded affirmatively; one participant in particular had a complete misunderstanding as to the social worker's involvement and the reasons for her and her brother being removed from their parental care. When asked whether she understood why the social worker had become involved she said:

"We were walking in the streets."

Because of a lack of information and understanding, this child incorrectly took the blame for what happened upon herself for her and her brother's removal. Pitchal (2008:20) rightly states:

"Few decisions are as enormous in our society as the decision to involuntarily remove a child from her [his] parents' custody and place her [him] in foster care. Children face the possibility of great psychological harm when separated from their families, even in cases where abuse is a factor."

The danger in incorrectly informing children - specifically children in middle childhood - or only partially informing them about the reasons for their removal from parental care is that they may incorrectly link their removal with an unrelated event, thus often taking the blame for the removal on themselves, which can have a negative effect on their functioning and self-awareness (Berk, 2013; Blom, 2006; Louw & Louw, 2014).

Furthermore as stated above, section 10 of the Children's Act 38 of 2005, Articles 12 and 13 of the UNCRC and Article 7 of the African Charter all recognise children's rights to receive age-appropriate information regarding anything that affects them (African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2009; Children's Act 38 of 2005; UNICEF, n.d.). Children should receive information in order to understand the reasons for the social worker's involvement. This information should be conveyed to the child at the very beginning of the court process, thus minimising misunderstanding and anxiety (Block Oran, Oran, Baumrind & Goodman, 2010; Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000).

When asked about verbal interaction with the social worker, only two of the children felt comfortable enough to speak openly with the social worker. Four children indicated that they did not want to divulge all the information to the social worker. This is exemplified by two responses:

"No ... because I was scared that [the social worker] would tell other people and that [the social worker] wouldn't keep it [information shared] between me and [the social worker]. "

"Still keep some things to myself."

When considering mutual communication, the importance of effective communication within the helping relationship, which is the cornerstone of the court process, is emphasised by Hepworth, Rooney, Rooney, Strom-Gottfried and Larsen (2010). They hold that in order to engage clients successfully, rapport must be established, where such rapport "reduces the level of threat and gains the trust of clients, who recognise that the social worker intends to be helpful" (Hepworth et al., 2006:35). As can be seen from the above excerpts in instances where the clients are children, establishing such rapport is even more important. Furthermore, abuse and neglect can impair children's emotional development, which can in turn lead to children struggling to understand the emotional responses and behavioural intentions of other people. Thus, it can be deduced that abuse and neglect can lead to deficits in knowledge regarding basic relationship skills (Wolfe, 1999:45). Because of these deficits, children may be wary of a social worker's attempts to build a relationship with them. This should be taken into consideration and adaptations should be made accordingly when social workers begin the investigative process with children. In the case of this research it did not seem that effective mutual communication had taken place and a positive rapport was lacking. This was further verified by the emotions that the children expressed regarding the involvement of the social worker, which were mostly negative. These emotions centred on feeling scared, sad or angry. With regard to feeling angry, one participant noted:

"She told us we were coming to the children's home."

Responses relating to fear were as follows:

"I was a bit [points to scaredface]. I hid under the couch."

"I was a bit scared the first time, but I am not scared anymore."

Notably, all participants were able to identify their own emotions towards the social worker or the situation. The above responses related to fear seem to highlight a difference in emotional intelligence, which involves the ability to identify and monitor one's own and others' emotions, to discriminate between the various emotions and then to use this information to guide one's own thinking and actions (Geldard, Geldard & Yin Foo, 2008; Kaur, 2010; Santrock, 2006). Although both participants had acted upon the emotion created by the situation, as a result of the interaction with her social worker, the first participant realised that the social worker would not remove her from her current placement, after which her fear decreased to some extent. The other participant did not interpret the situation correctly and simply acted on his emotion by hiding under the couch. This participant's fear was based on being removed from his current placement and it did not dissipate with time but remained heightened whenever he had any interaction with the social worker or the court process. This indicates a complete lack of a trusting relationship between the social worker and the child, which links with the importance of establishing rapport and developing a positive relationship in order for the child to trust the information given by the social worker that he would not be removed from his current placement.

Theme 2: Preparation for children's court

When asked whether they had been informed about the reason for them attending court, five participants indicated that they had not been informed, two had been informed and two could not remember. Resulting from this, the two participants, who had not been informed were under a misperception about the reasons for them attending court, stating:

"Cause they thought I do drugs and smoked and that."

"I thought we were going to be completely taken away from my mom."

With regard to the first participant's response, she had previously indicated that she thought she was at court because of something she had done wrong. Furthermore, her mother was a drug user at the time and this could explain her misconception. However, both responses highlight a lack of understanding as a result of not being adequately prepared for court.

The importance of preparing children for court and what they can expect, in a manner they can understand, should not be underestimated or downplayed. Empowerment and protection of the best interests of vulnerable children are paramount and this can only occur if professionals engage with children at their level and speak to them directly (African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2009; Children's Act 38 of 2005; Lefevre, 2010; UNICEF, n.d.). Something as simple as children having a proper understanding of why they are in court empowers them to begin the process of participating effectively during the various procedures (Erasmus, 2010; Warshak, 2003). Effective preparation also allows children to start formulating their own decisions regarding their future. Social workers should be mindful that children are the experts of their own lives. Ignoring this expertise will place these children at further risk (Holland & Scourfield, 2004; Nathanson & Shaw, 2015; Taylor, 2004).

In terms of participant knowledge of roles and procedures in the children's court, three participants indicated that they did not know what they should do in court and how the procedures work. With specific reference to the presiding officer, responses were more positive, with five participants indicating that they had been provided with limited information about the role of the presiding officer and only two indicated that they did not know the role of the presiding officer. However, the participants' knowledge of the role of the presiding officer seemed to extend only as far as knowing that he or she would ask questions. Furthermore, the participants did not know what type of questions they themselves would be asked. A lack of this type of knowledge places the children at a serious disadvantage and impairs their ability to participate effectively (Block et al., 2010; Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000; Taylor, 2004).

When exploring the emotions felt by participants about attending court, the main emotions were again negative, ranging from nervous to sad to scared. As can be seen in the responses below, when asked why they were experiencing the specific negative emotion, the responses appeared to centre on being unprepared for court:

"Because I never knew what I was doing there and I was scared I did something wrong and I felt guilty and I just wanted to go home."

"I did not know what was going to happen. "

"We will not see mommy and them."

"It was the first time in court. Scared I say wrong things."

"I thought I was never going home again."

"I thought they would take me away."

It is evident from these responses that the majority of the participants were not clear about what the end result of the court proceedings would be, and many had valid concerns that they would be removed from their parents' care or from the placement where they were at the time. The fears and concerns of these participants very likely created much anxiety that could easily have been minimised or completely avoided through adequate preparation. In fact, it is confirmed by various authors that a lack of courtroom knowledge has been indicated as a major source of anxiety for a participating child (Block et al., 2010; Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000). Louw and Scherrer (2004) rightly state that everything possible should be done to reduce the fear and uncertainty associated with the unfamiliarity of children's court procedures. Most especially, this should be done because children involved in court proceedings already experience trauma and disruption in their lives.

Furthermore, inadequate children's court preparation of children, particularly abused and neglected children, could lead to confusion and increased fear of the unknown as well as contribute to feelings of powerlessness, stigmatisation and betrayal (Block et al., 2010; Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000). McCoy and Keen (2009) as well as Copen (2000) state that children are less likely to experience additional trauma if they have been properly prepared for what to expect during the legal process. Consequently, they are also likely to feel less anxious and more in control, and will thus provide better testimony. This leads to the next theme, which relates to the appearance of participants in court and all the aspects related to this appearance.

Theme 3: First appearance in court and subsequent proceedings

This study made multiple findings related to this theme. Each finding is discussed below under the relevant sub-theme.

Interaction with presiding officers

Firstly, with regard to interaction with the presiding officer, two participants indicated that they did not feel that they could speak to the presiding officer. Furthermore, when exploring the interaction between the presiding officer and the participants, four indicated that they had not been asked any questions during the proceedings. A further four participants seemed to have been asked only where they wanted to stay or whether they were happy in the placement where they were in at the time. This type of questioning was especially stressful for one participant, who stated:

"He just asked me by who I want to stay ... then I wasn't sure what I must say because I was scared to upset my mom."

It is clear from the above response that this participant experienced a certain level of anxiety by having to verbalise her choice of where she would prefer to live and to do so in the presence of her mother, especially considering that her choice was to live with the foster parents rather than with her mother. This can be explained as a form of loyalty conflict where the child experiences feelings of guilt and fear of retribution, all of which could possibly damage the parent-child relationship (Kelly, 2002; Mahlobogwane, 2010).

Multiple authors suggest that if the presiding officer is to interview the child alone in chambers, such an interview would provide the child with the opportunity to speak freely (Abella, Heureux-Dubé & Rothman; Breger, 2010, as quoted in Mahlobogwane, 2010; Kelly, 2002). In addition, the presiding officer will be afforded the opportunity to interact directly with the child at the child's level. However, there are also disadvantages to this approach, such as the child feeling intimidated by the surroundings and the presiding officer (Mahlobogwane, 2010). Nevertheless, it does raise the question as to how the anxiety and discomfort levels of the participants, as mentioned above, may have been affected if she were asked where she would prefer to live without her mother and proposed foster mother being present.

Secondly, all the participants indicated that they themselves had not asked the presiding officer any questions. It seemed that three of these participants did not want to ask questions or interact with the presiding officer as they felt shy or scared. In support of this, one participant expressed himself particularly effectively, in comparison to the other participants, by simply stating:

"Because he looked scary."

Another participant's response seemed to centre on trust stating that he did not feel he could interact with the presiding officer:

"No, [be]cause he wasn't my social worke. "

These responses, in line with research conducted by Abella et al., (as quoted in Mahlobogwane, 2010; Kelly, 2002), highlight the possible presence of two disadvantages of interaction between the child and the presiding officer. Firstly, presiding officers fail to create a child-friendly environment in an inherently intimidating and stressful environment. Secondly, presiding officers rarely have the skills required to ask questions in an age-appropriate manner and to interpret answers correctly within the context (Abella et al., as quoted in Mahlobogwane, 2010; Kelly, 2002). These two disadvantages seemed to have been present in this current study, which hindered effective participation during the proceedings and subsequent decision-making processes (Abella et al., as quoted in Mahlobogwane, 2010; Kelly, 2002). Furthermore, had the participants in their preparation for children's court been alerted to the fact that they were permitted to interact and participate in the proceedings, and had an environment permitting such interaction and participation been created, they too might have raised aspects they wanted to ask questions about (Coogan & Parello, 2011; Grosman & Scherman, 2005; Pitchal, 2008). In order to participate effectively, children require information regarding the permissible interaction between children and the presiding officer (Pitchal, 2008).

It should be noted that, although the majority of participants indicated that they did not have any interaction with the presiding officer, one participant reported that the presiding officer specifically engaged her in conversation and asked where she would prefer to live. This highlights that where there is willingness, the process can be child-friendly and inclusive as allowed for by various legislation and policies.

Understanding of courtroom discussions

When participants were asked whether they understood what was being discussed during the court proceedings, only two of them indicated that they had understood what was being discussed. The majority of the participants indicated that they were bored and just sat there during the proceedings. Two participants even stated that they had been daydreaming.

Previous studies indicate that the language used by professionals during court proceedings is unfamiliar and confusing to children (Copen, 2000; McCoy & Keen, 2009; Sheehan, 2003). This seemed to be confirmed by this study as only two participants said that they understood what was being discussed during proceedings. When linking these findings with the fact that no professional in the court ensured that the participants understood what was being discussed, these results are a cause for great concern. If children do not understand what is being discussed, they cannot be expected to participate effectively. This is especially worrying when taking into consideration that five participants expressed their desire to understand what was being discussed, with only one indicating that he did not want to understand.

Accordingly, research conducted by Butler, Scanlan, Robinson, Douglas and Murch (2003) confirms that it is not only desirable but also feasible to consult with children when decisions about their future are being made, concluding that even children as young as five years are able to contribute positively to this decision-making process. Since decisions made regarding children's future can have severe repercussions for such children, they ought to be provided with multiple opportunities to express their views and to interact during the proceedings (Barratt, 2003; Lefevre, 2010; Mahlobogwane, 2010; Taylor et al., 2007). This was not done with any of the participants in this study.

Emotions related to court attendance

Similar to the emotions identified by participants in relation to other aspects of the children's court procedures, when asked about their emotions before or during court proceedings, responses were negative, focused on feelings of fear. Two participants worried about being taken away from their parents/care givers, as indicated by their responses:

"I thought I was not going home again."

"Because I thought they wanted to take me away."

One participant appeared to be nervous, sad and worried because of her uncertainty about the proceedings:

"Because I never knew what I was doing there and I was scared I did something wrong and I felt guilty and I just wanted to go home ... that I did something wrong to someone or I stole something but I didn't."

Emotions are viewed as being interwoven with cognitive processing. Consequently, emotion - such as the strong negative emotions described by the participants in this study - can impair a child's ability to think and reason (Berk, 2013; Louw & Louw, 2014). This may be especially true when taking into consideration that these children are fearful of being removed from their parents/care givers or never seeing their parents/care givers again. As indicated by Eltringham and Aldridge (2000), in order to empower children, professionals ought to be preparing them appropriately for the children's court process and provide them with the support they require. If these fundamental factors are not addressed, the current court system is disempowering and disrespectful to children and has a high probability of doing great damage to the dignity and self-worth of the children involved (Pitchal, 2008). The emotions identified by the participants during the interviews conducted for this study indicate disempowerment.

Perceptions of participants of regular children's court attendance

Of the nine participants, two endured regular postponements. This required regular attendance of court. Neither participant experienced this positively:

"No it is also not nice for me because the court is actually for criminals and stuff, it is not nice for me to be there."

"I thought it was a jail ... that there is jails there and that is where people that did wrong things go."

Despite the fact that both participants made reference to the "jail" aspect of court, their understanding of how this aspect linked with themselves was vastly different. The first participant's response seemed to indicate an understanding that, although court is where criminals go, she herself was not a criminal and had done nothing "bad." However, the knowledge that criminals were also appearing in court at the same time she was, albeit in another part of the building, made her feel uneasy.

Because of the first participant's background, where her mother was often in conflict with the law, and her resultant frame of reference Blom (2006), her response was coloured by views of court being a place where "bad people go." Furthermore, at age 9 this participant was in Piaget's heteronomous phase of moral development (cf. Louw & Louw, 2014). This stage is characterised by a strict respect for rules and an almost blind obedience of said rules (Louw & Louw, 2014; Santrock, 2006). Thus it could be argued that this participant's strict respect for and adherence to "rules" led to her reasoning that because only "bad" people go to court, she must be "bad" too or must have done something "bad." This incorrect understanding and the resultant anxiety and possible confusion could have been avoided had the participant been adequately prepared (Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000).

In their study Block et al. (2010) found that children often display negative attitudes towards the court system. These negative attitudes can be associated with not having received any preparation for the proceedings. In the current study participants also did not receive preparation and, as is confirmed by the above participant quotes, they displayed both uneasiness and negativity about attending court.

After children have attended court, often multiple times, the presiding officer will make a decision regarding the child's future care. This is done during the finalisation of proceedings and is discussed below.

Theme 4: Finalisation of proceedings

As mentioned above, the presiding officer will give his or her final decision in the presence of all key stakeholders. However, when participants in this study were specifically asked whether the presiding officer had informed and explained the ruling to them, six participants indicated that nothing had been explained to them. When asked whether they understood what the ruling meant, only one participant indicated that he had understood. With regard to understanding the ruling, one participant who had been placed in foster care responded as follows:

"Now [I understand] then [during finalisation] I did not know so much [why I was being placed in foster care]. "

This uncertainty created a certain level of confusion and anxiety that was evidently addressed only much later, after placement into foster care, and could potentially have had a negative effect on the child's functioning (Block et al., 2010; Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000; Louw & Louw, 2014; Taylor, 2004) Furthermore, this uncertainty and lack of understanding undermine the right of the child to be provided with age-appropriate information, which would include information on the final outcome of the proceedings, as well as the child's right to be brought up in a stable family environment where he/she is protected from psychological harm that could be result from uncertainty about his/her long-term care (African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2009; Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 16th amendment, Act 1 of 2009; Children's Act 38 of 2005; UNICEF, n.d.).

Participants were then asked whether they agreed with the ruling in terms of their placement; four participants indicated that they did not agree. Two of these participants who did not agree were placed in child and youth care centres and one in a place of safety. As can be deduced from the above, the final ruling and reasons for such a ruling were not discussed with the participants, resulting in a certain degree of confusion, anxiety and disempowerment (Eltringham & Aldridge, 2000; Pitchal, 2008). Keeping with the standard of the best interests of the child, as required by various pieces of legislation in South Africa, it could be postulated that providing a child with an adequate explanation as to the reason for his or her placement will surely be in that child's best interests and wellbeing (African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2009; Children's Act 38 of 2005; Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 16th amendment, Act 1 of 2009; Pitchal, 2008; UNICEF, n.d.).

Theme 5: Children's response to physical structure of the children's court

Since this study set out to examine children's experiences of children's courts holistically, it would be incomplete if their view of the actual court building itself were not also investigated, hence the inclusion of this theme. Eight participants in this study indicated that there had not been an area where they could play while they waited. In fact, these eight participants had to wait in the same area as the adults who were awaiting trial until their case was called, and four participants clearly stated that they found this to be very boring. Without exception, all participants stated that it would have been nice to have a play area where they could be kept busy while waiting. Of the nine, only one participant indicated that she and her foster parent waited in a play area where there were toys she could play with. Despite being the only participant who had access to a play area, it was interesting to note that she did not make use of it.

This study made similar findings to a South African study conducted by Louw and Scherrer (2004), where they asked children to comment on what they experienced as positive within the environment of the Office of the Family Advocate, where divorce investigations are conducted. These children, as in the researcher's study, responded that they had liked that there were magazines, toys and things to draw with while they waited. They further commented that a comfortable waiting area with a TV was something they enjoyed.

Despite the fact that the participants in this study expressed no further emotions with reference to having to wait for their case to be called, Louw and Scherrer (2004) indicated that having to wait could be stressful. They are also of the opinion that in order to "soften" the emotional effect of this waiting period, everything possible should be done to make the waiting area more child-friendly. Jenkins (2008) is also of the view that courts in general ought to be more child-friendly, a notion to which this researcher fully subscribes, since the creation of an environment where children's fears and anxieties are alleviated while they await their appearance in court - a system dominated by adult presence - would surely aid their ability to participate effectively in children's court proceedings.

The conclusions of this research are presented below.

CONCLUSIONS

The main aim of the research reported here was to explore the experiences of children in middle childhood regarding children's court procedures. Relevant literature regarding legislation, policies and current practice was reviewed. Although some of the literature was dated, because of the lack of current literature regarding this topic, all the literature scrutinised was rich in information and relevant to this study.

The findings of the research highlighted two key findings: firstly, in terms of the lack of preparation of children about the procedures in the children's court; and secondly, the fact that children do not appear to participate in the court proceedings in any meaningful way. When taking into consideration the extensive provision for the participation of children as well as the acknowledgement of the rights and best interests of children that is evident in legislation and policies, both nationally and internationally, it is disappointing that the implementation of said legislation and policies is flawed in this way.

Based on the two key findings mentioned above, it can be concluded that, as a result of the inadequate preparation of children about procedures in the children's court, children often do not understand why they are attending children's court and they are not informed about the roles and responsibilities of all of the stakeholders, including themselves. This leads to misconceptions, uncertainty about their future, feelings of fear and anger and overall anxiety, which in turn have a negative influence on the child's experience of children's court procedures.

Furthermore, this study found that, although children are present during children's court proceedings, they do not participate effectively. Sometimes they do not participate at all. Because of inadequate preparation before their appearance in the children's court, the majority of children do not get involved in the proceedings and merely sit quietly while the professionals and adults discuss their case. Those who attempt to listen to the proceedings do not understand, as the legal language used in court by professionals is unfamiliar and can be confusing to children (Copen, 2000; McCoy & Keen, 2009; Sheehan, 2003). In addition, presiding officers do not appear to explain their rulings to the children during finalisation and this causes the children to experience negative emotions, especially since the majority indicated that they did not agree with the ruling and would have preferred another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to address all of the aspects mentioned above it is essential that social workers be able to build rapport with children before children's court procedures and maintain this rapport throughout the process. Furthermore, through this relationship the social workers should be able to prepare children effectively for all aspects related to the various procedures in the children's court. This preparation can be done by using a professionally designed and empirically tested preparation programme. No specific programme to prepare children for the procedures in the children's court exists in South Africa, which leads to the recommendation for further study and development of such a programme.

Furthermore, presiding officers would benefit from training in how to effectively communicate and interact with children in order to ensure maximum understanding and participation by each child. However, as was noted in the discussion above where presiding officers are willing and able, the interaction between child and presiding officer can be used effectively and to the benefit of both the child and the process. The interaction between child and presiding officer as well as possible future training areas also requires further research and the design of such a training programme.

Little or no research which focuses on the child's experience of court from the child's perspective has been published in South Africa. Instead, published research in this field is often solely focused on the experiences of children from the perspective of the stakeholders. This makes this research unique and makes the contribution of this research valuable. Furthermore, this research was able to answer the initial research question by identifying that children tend to experience children's court procedures negatively. The main reason for this negative experience seems to be the fact that children are ineffectively - or not at all - prepared for procedures in the children's court. When we consider the harmful and at times lifelong effect of negative experiences of children's court procedures, and note the large number of children who pass through the children's court system annually, the lack of preparation for the procedures in the children's court found in this research is a cause for great concern.

REFERENCES

AFRICA, A., DAWES, A., SWARTZ, L. & BRANDT, R. 2003. Criteria used by family counsellors in child custody cases: a psychological viewpoint. In: BURMAN, S. (ed), The fate of the child: legal decisions on children in the new South Africa. Lansdowne: Juta Law. [ Links ]

AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS AND WELFARE OF THE CHILD, OAU Doc. 2009. [Online] Available: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/africa/afchild.htm [Accessed: 12/03/2013]. [ Links ]

BAINHAM, A. & GILMORE, S. 2013. Children: the modern law. (4th ed). Bristol Jordan Publishing. [ Links ]

BALA, N., TALWAR, V. & HARRIS, J. 2005. The voice of children in Canadian Family Law Cases. Canadian Family Law Quarterly, 24(3):221-279. [ Links ]

BARRATT, A. 2003. 'The best interest of the child': Where is the child's voice? In: BURMAN, S. (ed), The fate of the child: legal decisions on children in the new South Africa. Lansdowne: Juta Law. [ Links ]

BARRIE, G.N. 2011. The best interests of the child: lessons from the first decade of the new millennium. Journal of South African Law, 26(1): 126-134. [ Links ]

BERK, L.E. 2013. Child Development (9th ed). Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

BILSON, A. & WHITE, S. 2005. Representing children's views and best interests in court: an international comparison. Child Abuse Review, 14(4):220-239. [ Links ]

BLOCK, S.D., ORAN, H., ORAN, D., BAUMRIND, N. & GOODMAN, G.S. 2010. Abused and neglected children in court: knowledge and attitudes. Children Abuse and Neglect, 34(1):659-670. [ Links ]

BLOM, R. 2006. The handbook of gestalt play therapy: practical guidelines for child therapists. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

BREGER, M.L. 2010. Against the dilution of child's voice in court. Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 20(2):175-194. [ Links ]

BUTLER, I., SCANLAN, L., ROBINSON, M., DOUGLAS, G. & MURCH, M. 2003. Divorcing children: children's experiences of their parents' divorce. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

CHILDREN'S ACT 38 OF 2005. Published in the Government gazette, (28944) Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 16th AMENDMENT ACT 1 OF 2009. Published in the Government gazette, (32065) Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

COOGAN, M. & PARELLO, N. 2011. A child's voice: involving youth in child protection court hearings. [Online] Available: http://www.acnj.org/main.asp?uri=-1003&di=2022 [Accessed: 03/05/2013]. [ Links ]

COPEN, L.M. 2000. Preparing children for court: a practitioner's guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. (3rd ed). Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

DAVEY, C., BURKE, T. & SHAW, C. 2010. Children's participation in decision making: A children's views report. London: National Children's Bureau. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE. 2014. Annual report children's court matters 2013/2014. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DIDUCK, A. 2003. Law's families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

ELTRINGHAM, S. & ALDRIDGE, J. 2000. The extent of children's knowledge of court as estimated by Guardians ad Litem. Child Abuse Review, 9(1):275-286. [ Links ]

ERASMUS, D. 2010. 'There is something you are missing; What about the children?': separating the rights of children from those of their caregivers. South Africa Public Law, 25(1):124-136. [ Links ]

FORTIN, J. 2009. Children's rights and the developing law (3rd ed). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

FOUCHE, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions. (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

GELDARD, K., GELDARD, D. & YIN FOO, R. 2013. Counselling children: a practical introduction. (4th ed). London: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

GREEFF, M. 2011. Information collection: Interviewing. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

GROSMAN, C.P. & SCHERMAN, I.A. 2005. Argentina: criteria for child custody decision-making upon separation and divorce. Family Law Quarterly, 39(2):543-562. [ Links ]

HALL, K. 2010. Income and social grants - foster child grants. [Online] Available: http://www.childrencount.ci.org.za/indicator.php?id=2&indicator=39 [Accessed: 2012/09/10]. [ Links ]

HALL, K. 2012a. Demography - Children in South Africa. [Online] Available: http://www.childrencount.ci.org.za/indicator.php?id=1&indicator=1 [Accessed: 2012/09/10]. [ Links ]

HALL, K. 2012b. Income and social grants - Foster child grants. [Online] Available: http://www.childrencount.ci.org.za/indicator.php?id=2&indicator=39 [Accessed: 2012/09/10]. [ Links ]

HEATON, J. 2009. An individualised, contextualised and child-centred determination of the child's best interests, and the implications of such an approach in the South African context. Journal of Juridical Science, 34(2):1-18. [ Links ]

HEATON, J. 2012. South Africa: changing the contours of child and family law. In: SUTHERLAND, E.E. (ed). The future of child and family law: International predictions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HEPWORTH, D.H., ROONEY, R.H., ROONEY, G.D., STROM-GOTTFRIED, K. & LARSEN, J.A. 2010. Direct Social Work Practice: theory and skills (8th ed). Belmont: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

HOLLAND, S. & SCOURFIELD, J. 2004. Liberty and respect in child protection. British Journal of Social Work, 34(1)21-36. [ Links ]

JAMES, A. 2003. 'Squaring the circle - The social, legal and welfare organisation of contact. In: BIRNAM, A. LINDLEY, B., RICHARDS, M. & TRINDER, L. (eds), Children and their families: contact, rights and welfare. Oregon: Hart Publishing. [ Links ]

JENKINS, J.J. 2008. Listen to me! Empowering youth and courts through increased youth participation in dependency hearings. Family Court Review, 46(1): 163-179. [ Links ]

KAGANAS, F. & DIDUCK, A. 2004: Incomplete citizens: changing images of post separation children. Modern Law Review, 67(6):959-981. [ Links ]

KAUR, J. 2010. Gender difference in emotional intelligence among Indian adolescents. Journal of Social & Psychological Sciences, 3(2):41-52. [ Links ]

KELLY, J.B. 2002. Psychological and legal interventions for parents and children in custody and access disputes: current research and practice. Virginia Journal of Social Policy and Law, 10(1):129-163. [ Links ]

LEESON, C. 2007. My life in care: experiences of non-participation in decision-making processes. Child and Family Social Work, 12(3):268-277. [ Links ]

LEFEVRE, M. 2010. Communicating with children and young people: making a difference. Bristol: The Policy Press. [ Links ]

LOUW, D. & LOUW, A. 2014. Child and adolescent development (2nd ed). Bloemfontein: Psychology Publications. [ Links ]

LOUW, D.A. & SCHERRER, R. 2004. Children's perception and experience of the family advocate system. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 32(1):17-37. [ Links ]

MAHLOBOGWANE, F.M. 2010. Determining the best interests of the child in custody battles: should a child's voice be considered? Obiter, 31(2):232-246. [ Links ]

MATTHIAS, C.R. & ZAAL, F.N. 2010. Domestic violence perpetrator removals: unpacking the new children's legislation. Stellenbosch Law Review, 21(3):528-541. [ Links ]

McCOY M.L. & KEEN, S.M. 2009. Children abuse and neglect. New York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

MEINTJES, H. & HALL, K. 2012. Demography - Orphanhood. [Online] Available: http://www.childrencount.ci.org.za/indicator.php?id=1&indicator=4 [Accessed: 2012/09/10]. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, J. 2006. Children Act private law proceedings: A handbook. (3rd ed). Bristol: Jordan Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

NATHANSON, R. & SAYWITZ, K.J. 2015. Preparing children for court: Effects of a model court education programme on children's anticipatory anxiety. Behavioural Sciences and the Law, 33(1)459-475. [ Links ]

NATIONAL BUDGET REVIEW. 2013. [Online] Available: http://www.treasury.gov.za/-documents/national%20budget/2013/review/chapter%206.pdf [Accessed: 04/04/2013]. [ Links ]

NEUMAN, W.L. 2011. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th ed). Boston: Allyn & Bacon Publishers. [ Links ]

PARKINSON, L. 2006. Child-inclusive family mediation. Family Law, 36(6):483-488. [ Links ]

PITCHAL, E.S. 2008. Where are all the children? Increasing youth participation in dependency proceedings. Journal of Juvenile Law & Policy, 12(1): 1-31. [ Links ]

PRILLELTENSKY, I., NELSON, G. & PEIRSON, L. 2001. The role of power and control in children's lives: an ecological analysis of pathways toward wellness, resilience and problems. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11(2):143-158. [ Links ]

PRINSLOO, J. 2008. In the best interest of the child: the protection of child victims and witnesses in the South African Criminal Justice System. Child Abuse Research, 9(2):49-64. [ Links ]

RATIFICATION TABLE: AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS AND WELFARE OF THE CHILD. 2013. [Online] Available: http://www.achpr.org/instruments/-achpr/ratification/ [Accessed: 2013/03/12]. [ Links ]

ROSA, S. & DUTSCHKE, M. 2006. Children's rights at the core: the use of international law in South African cases on children's socio-economical rights. South African Journal on Human Rights, 22(2):224-260. [ Links ]

SANTROCK, J.W. 2006. Life-span development (10th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers. [ Links ]

SAYWITZ, K., JAENICKE, C. & CAMPARO, L. 1990. Children's knowledge of legal terminology. Law and Human Behavior, 14(6):523-535. [ Links ]

SHEEHAN, R. 2003. The marginalization of children by the legal process. Australian Social Work, 56(1):28-39. [ Links ]

SMART, C., NEALE, B. & WADE, A. 2001. The changing experience of childhood: families and divorce. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION/UNICEF. 2011a. South Africa's Children - A review of equality and child right's. [Online] Available: http://-www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAFresources factschildrens11.pdf [Accessed: 2015/11/24]. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION/UNICEF. 2011b. South Africa's Children - A review of equality and child right's. [Online] Available: http://-www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAFresourcesfactschildrens22.pdf [Accessed: 2015/11/24]. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2015. Mid-year population estimates. [Online] Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022015.pdf [Accessed: 24/11/2015]. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2011. Sampling and pilot study in qualitative research. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds). Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4 th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. 2011. Ethical aspects of research in the social sciences and human service profession. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, L.T. 2013. The experiences of children in middle-childhood regarding Children's Court procedures. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (MSW MiniDissertation) [ Links ]

TAYLOR, C. 2004. Underpinning knowledge for child care practice: reconsidering child development theory. Child and Family Social Work, 9(3):225-235. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, N., TAPP, P. & HENAGHAN, M. 2007. Respecting children's participation in family law proceedings. International Journal of Children's Right's, 15(1):61-82. [ Links ]

THOMAS, N. & O'KANE, C. 2000. Discovering what children think: connections between research and practice. British Journal of Social Work, 30(6):819-835. [ Links ]

UNICEF. [Sa]. Fact Sheet: A summary of the rights under the Convention of the Rights of the Child. [Online] Available: http://www.unicef.org/crc/files/-Rightsoverview.pdf [Accessed: 10/09/2012]. [ Links ]

WADE, A. & SMART, C. 2002. Facing family change: children's circumstances, strategies and resources. York: York Publishers. [ Links ]

WARSHAK, R.A. 2003. Payoffs and pitfalls of listening to children. Family Relations, 54(4):373-384. [ Links ]

WOLFE, D.A. 1999. Child abuse: implications for child development and psychopathology. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

ZAAL, F.N. 2003. Hearing the voices of children in court: a field study and evaluation. In: BURMAN, S. (ed), The fate of the child: Legal decisions on children in the new South Africa. Lansdowne: Juta Law. [ Links ]