Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 n.3 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-511

ARTICLES

Relational aspects of family functioning and family satisfaction with a sample of families in the Western Cape

Nicolette V Roman; Catherina Schenck; Jill Ryan; Fairoza Brey; Neil Henderson; Novuyo Lukelelo; Marie Minnaar-McDonald; Valerie Saville

Child and Family Studies, Department of Social Work, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Family functioning may affect how satisfied family members are within the family. This study assessed the relational aspects between family functioning and family satisfaction with a conveniently sampled group of families. This study applied a quantitative methodology with a cross-sectional correlational design. The sample consisted of 204 participants (57% females, 50% Black Africans and 39% speaking isiXhosa). The average age was 31 years (SD=11.07). The results suggest that families could be at risk in terms of family functioning and this predicted being satisfied with the family. Implications for social work practice are provided.

INTRODUCTION

Globally the family is perceived as the most enduring social unit central to the healthy functioning of individuals and the broader society (Hochfeld, 2007:79). Families are the primary source of individual development and the primary setting in which children begin to acquire their beliefs, attitudes, values and behaviours considered as appropriate to society (Ogwo, 2013:225). The term "family" previously referred to two married people of both sexes and their children. One of the oldest definitions was given by Murdock (1949), who stated that a family "is a social group characterised by common residence, economic cooperation and reproduction. It includes adults of both sexes at least two of whom maintain a socially approved sexual relationship and one or more children". However, this definition limits other forms of families that have developed recently. The White Paper on Families defines families as societal groups of members related by blood (kinship), adoption, foster care or ties of marriage (extended families), including civil, customary, or religious marriages, or communal union, and extends beyond any particular shared physical residence (Department of Social Development, 2013:11). It is through this definition that the White Paper on Families encapsulates the diverse nature of families. Families are guided by three key strategic priorities aimed at guiding the core functions of the family. These key priorities include (1) the promotion of healthy family life, which focuses on the efforts preventing the breakdown of family life by promoting positive attitudes and values about the importance of strong families within communities; (2) family strengthening refers to the deliberate process of giving families the necessary opportunities, relationships, networks, support and protection during times of adversity and social change; and (3) family preservation, which generally refers to keeping families together with specific programmes intending to strengthen families during crises (Department of Social Development, 2013:37,38). In essence, these strategic priorities are designed to strengthen families so that there are improvements in the way families function and interact.

Belsey (2005:11) states that the manner in which families function provides a way of incorporating individuals into social life and it provides the source of emotional, influential and material support for its members. Similarly, Walker and Shepherd (2008:1) define family functioning in relation to how family members communicate with each other, relate to one another, maintain relationships, and make decisions and solve problems together. As a result, family functioning can be seen as a multidimensional concept which denotes how family members interact with one another and collaborate in achieving a common goal and outcome (Botha & Booysen, 2013:164).

Family functioning affects individual wellbeing to the extent that satisfactory levels of social support within families are important to the happiness of an individual (Botha & Booysen, 2013:168). This may be attributed to how well the family members engage with and support each other, especially when assisting members to manage difficult or traumatic life experiences (Vliem, 2009:18; Walker & Shepherd, 2008). When the family is functioning well, a positive sense of wellbeing is established, which negates chances of psychological issues developing and enhances the family's problem-solving abilities by creating a sense of togetherness (Caprara, Pastorelli, Regalia, Scabini & Bandura, 2005:90; Vliem, 2009:18). Positive family functioning creates an environment where the family members support and accept each other and together engage in activities further facilitating child development. These positive family traits, however, do not occur in families experiencing maladaptive functioning (Becvar & Becvar, 2009; Nichols, 2010). Families experiencing substance abuse, family violence, challenged parenting practices and poor communication show dysfunctional family factors such as maladaptive parenting, child neglect and abuse as well as a vulnerability to pathological disorders (Kessler et al., 2010:378,380).

In South Africa research on family functioning is limited. In South African research highlighting family functioning and wellbeing the main focus has been on parent-child relationships and the marital relationship (Armstrong, Birnie-Lefcovitch & Ungar, 2005; Bornstein & Zlotnik, 2009). A study recently highlighted South African families as being distinctively challenged because of single parenthood, poverty, unemployment, absent fathers and risk-taking behaviour (Holborn & Eddy, 2011). However, their study does not examine the family's internal process in dealing with these external challenges, such as how the family functions as a unit in order to overcome challenges. As previously mentioned, family functioning refers to communication, problem-solving, role assignment as well as emotional affect between family members and their behaviour. A recent South African study (Koen, Van Eeden & Rothmann, 2013:409) examining the psychological wellbeing of families in the North-West Province suggests that family functioning is one of two factors accounting for family psychosocial wellbeing. The other factor, family feeling, is denoted by trust and belongingness between family members. which is strongly affiliated to family satisfaction. The two factors strongly correlate to family cohesion and are indicative of family satisfaction, resilience and attachment. Given how important the family is, it has become increasingly clear that the state of family wellbeing in South Africa is affected by changes in the economic, social, political and technological environment. The ability of families to survive these changes suggests that families are flexible and that their flexibility is aided by how families function (Department of Social Development, 2013; Walsh, 2006). For the purposes of prevention and intervention programmes to strengthen families, it would be important to study the family in order to assess how families function (Shokoohi-Yekta, Paranda & Ahmadi, 2011) especially in a resource-constrained country such as South Africa. The current study used the family assessment device to assess family functioning (problem solving, behavioural control, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, general family functioning and communication) and sought to investigate the extent to which family functioning predicts being satisfied with the family.

METHODS

A quantitative cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted with a convenient sample of families. Convenience sampling uses a sample of participants who are conveniently available to the researcher, and is useful as a starting point in the case that there is little evidence on a particular issue (Loiselle, Profetto-McGrath, Polit & Beck, 2011), as would be the case for the current study. In this study students in the fourth-year research group studying social work invited one adult family member of three families living in close proximity to their homes. The majority of social work students live on the Cape Flats. The final sample was 204 participants representing 204 families.

Research instrument

The data-collection instrument included three sections: Section A was the demographic section, which included details of gender, age, home language, race and family structure. Section B consisted of the Family Assessment Device (Epstein, Baldwin & Bishop, 1983) and the Satisfaction with Family Scale was included in Section C.

Family functioning (The Family Assessment Device, Epstein et al., 1983)

The Family Assessment Device was developed to assess the family based on certain factors such as communication, problem solving, behaviour control, affective involvement, affective responses and roles. Family members rate how well each statement describes their family by selecting from among four alternative responses ranging from 1 = Strongly Agree to 4 = Strongly Disagree. Cronbach's alphas ranged between 0.70 - 0.81. Items include "We make sure members meet their family responsibilities", "We cannot talk to each other about the sadness we feel" and "We usually act on the decisions we made regarding problems."

The Satisfaction with Family Scale was created from an adaptation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985). This is a 5-item scale and seeks to assess how satisfied family members are with their families. Examples of some of the items are "In most ways my family is close to my ideal" and "I am satisfied with my family." Participants responded on 7-point Likert scale ranging from extremely dissatisfied to extremely satisfied. Cronbach's alpha was acceptable at 0.82.

Ethical consideration

Permission to conduct the study was provided by the Senate Research Ethics Committee at the University of the Western Cape. In preparation for the data-collection process the students were trained to understand and implement the research instrument. They were also trained regarding the adherence to the code of research ethics of the university, which included confidentiality and anonymity of participants, informed consent and the right to non-participation and withdrawal.

Data-collection procedure

When approaching the participants at their homes, the researchers (students) explained the aim and objectives of the study, the focus of the questions in the questionnaire and what the expectations of the data-collection process would be. Once everything had been explained to the participants and they agreed to participate, they signed a consent form and the researcher assisted in the completion of the questionnaire.

Data analysis

The data were cleaned, coded and entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v22). Descriptive statistics such as percentages, means and standard deviations were used to conduct the analysis. Relationships between variables were assessed by means of the Pearson Moment Correlation and a regression analysis.

RESULTS

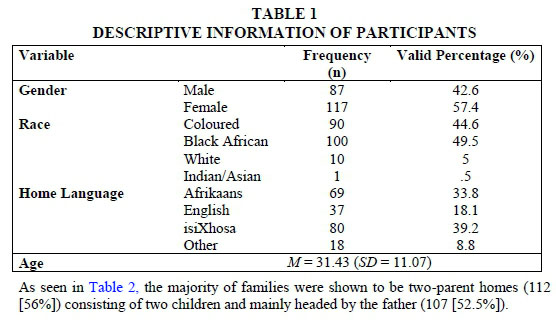

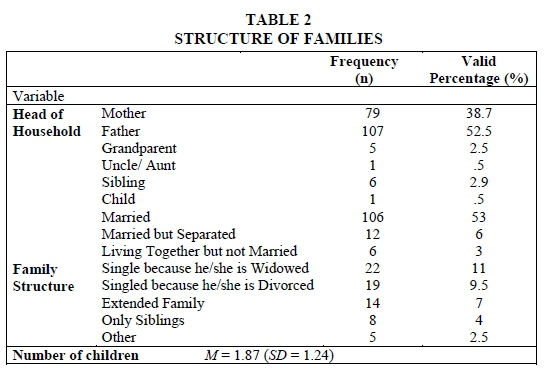

The results in Table 1 show that the majority of the participants were female [117 (57%)]. Most of the participants who participated in the study identified themselves as Black African [100 (50%)] with isiXhosa [80 (39%)] shown as the predominant language spoken by participants. The average age of participants was 31 years (SD = 11.07).

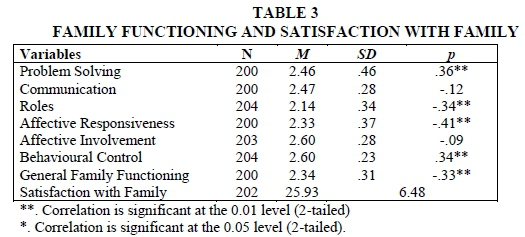

Table 3 highlights the findings of the relational aspects between family functioning and being satisfied with the family. Based on the scoring for the FAD, Epstein et al. (1983) found that stressed families or at-risk families scored on average higher than 2.00 as a Mean Score on the subscales, except for behavioural control in the family, which was 1.90. In the current study the participants perceived the functioning in their families as stressed, with all subscales having a Mean Score of above 2.00. The highest scores were for affective involvement (M = 2.60, SD = -.09) and behavioural control (M = 2.60, SD = .23) in the family. The lowest score was for roles (M = 2.14, SD = .34). However, participants scored fairly high for being satisfied with their families (M = 25.93, SD = 6.48). The results of the correlation suggest that there are significant positive relationships between SWF and problem solving (r = .36, p < .01) as well as behavioural control (r = .34, p < .01). There were also significant negative relationships between SWF and roles (r = -.34, p < .01), affective responsiveness (r = .41, p < .01) and general family functioning (r = -.33, p < .01).

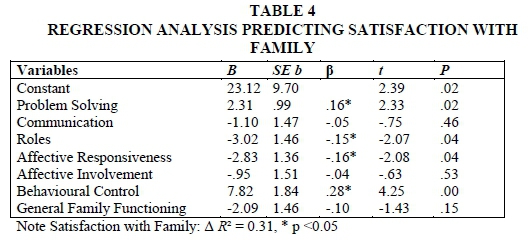

A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess which of the family functioning variables predicted being satisfied with the family. The results in Table 4 show that roles (β = -.15, p = .04) and affective responsiveness (β = -.16, p = .04) negatively predicted being satisfied with the family. Furthermore, problem solving (β = .16, p = .02) and behavioural control (β = .28, p = .00) in the family positively predicted satisfaction with the family. The final model accounted for 31% of the variance for SWF.

DISCUSSION

In the current study we sought to ascertain the relational aspects between family functioning and being satisfied with the family.

Family functioning is a multidimensional concept referring to the interrelatedness of family members (Belsey, 2005; Botha & Booysen, 2013; Vliem, 2009). Based on the Family Assessment Device (FAD), the higher the mean score is above 2.00, the more stressed the family is perceived to be by family members (Epstein et al., 1983). In the current study functioning in the family was perceived as dysfunctional for the majority of the sample, which equated to families being considered to be at risk. The most challenging functions in the family were perceived as behavioural control and affective involvement. According to Miller et al. (2000:171-172), behavioural control in the family is defined as the patterns the family adopts in the following situations: (1) physically dangerous situations, (2) meeting and expressing psychobiological needs or drives, and (3) interpersonal socialising behaviour. Affective involvement is defined as "the degree to which the family as a whole shows interest in and values the activities and interests of individual family members". According to Botha and Booysen (2013), the way in which families function may affect the wellbeing of family members and in particular the way in which they relate and interact with each other. These results could be a start to understanding the breakdown of the South African family as indicated by Holborn and Eddy (2011), who found that families were challenged in multiple ways. Their research highlights high prevalence rates of absent fathers, single mothers, single- and double-orphaned children, the effects of violence in families and communities. The results of the current study could be considered similar to results found in a recent South African study in which participants indicated that there were low levels of psychosocial wellbeing in the family (Koen et al., 2013). Psychosocial wellbeing was indicated by family functioning, family satisfaction and family feelings. If families were not functioning very well, the question was how satisfied would participants be with their families.

Participants scored fairly high, indicating that they were satisfied with their families. Individuals who attained high on family satisfaction were likely to have family and friends who were close and supportive. In terms of this score, which is interpreted in the same category (25-29 score) of the SWLS (Diener et al., 1985), while families may not be perfect, participants could be realistic and positive about their families. Being satisfied with the family in the current study was a similar finding to a local study conducted by Koen et al. (2013). The findings were also consistent with an international study which indicated that open communication, parental monitoring and quality of family interactions predicted family satisfaction (Caprara et al., 2005:74).

In the current study family functioning significantly predicted being satisfied with the family. In fact, the final model accounted for 31% of the variance of family satisfaction. Specifically, roles and affective responsiveness negatively affected being satisfied with the family. Roles within the family are defined by Epstein et al. (1983:172-173); they are:

"The established patterns of behavior for handling a set of family functions, which include provision of resources, providing nurturance and support, supporting personal development, maintaining and managing the family systems and providing adult sexual gratification. In addition, assessment of the roles dimension includes consideration whether tasks are clearly and equitably assigned to family members and whether tasks are carried out responsibly by family members."

If family roles and responsibilities are not equally distributed amongst family members, there may be a sense of unfairness and this may cause anger and dissension amongst family members. This becomes particularly relevant in families where there is an imbalance in gender roles and responsibilities (Holborn & Eddy, 2011:9). This is highlighted in the research focusing on work-family relationships and wellbeing, where women often carry the heavier burden of child and family care than men do (Department of Social Development, 2013:19,23) and understandably this may reduce being satisfied in the family.

For affective responsiveness, "family members are able to experience appropriate affect over a range of stimuli. Both welfare and emergency emotions are considered" (Epstein et al., 1983:172-173). In this definition, it is clear that warmth, love, nurturance, sensitivity and consistency of responses within the family are important for family members to feel a sense of belonging. This is in line with the research on self-determination theory, which highlights that in order for individuals to function optimally and be psychologically well, three basic psychological needs should be met. These are autonomy, relatedness (belonging) and competence (Ryan & Deci, 2008). In the current study, affective responsiveness significantly negatively affected being satisfied in the family possibly as a result of the nature of the responses provided within the family.

The results also indicate that problem solving and behavioural control in the family positively affect being satisfied with the family. Epstein et al. (1983:172-173), the creators of the family functioning questionnaire, define the assessment of problem solving as "the family's ability to resolve problems (issues which threaten the integrity and functional capacity of the family) at a level that maintains effective family functioning", and behavioural control as the standards by which family members behave and how they express these standards of behaviour for the family. The research shows that when families are able to appropriately and effectively solve problems within the family, functioning within the family is more stable and less at risk (Walsh, 2006). Furthermore, the family has a sense of cohesion and therefore feels a sense of relatedness and belonging, which may reduce childhood disorders and improve family functioning (Shokoohi-Yekta et al., 2011). Similarly when families are functioning well, children are disciplined, well behaved and are psychologically well (Owragi, Yousliani & Zarnaghash, 2011), and may therefore be satisfied with their families.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study confirms, with other studies mentioned, that South African families are in distress. Symptomatically this is evident in the high crime rate, substance abuse and family disintegration. A need for affective involvement and behavioural control touches the core of the person, the family and the society. The wellbeing of the person and society is directly linked to the functioning of the family, which should provide care and protection to the individual and social cohesion for the entire society.

The SA Family Policy (2013) also acknowledges the distress of family life and supports the view that families contribute to societal stability and hence urgent attention should be given to our family life on macro, meso and micro levels. The family policy lists all the important aspects which need to be addressed to strengthen and support family functioning and preserve families in a rights-based and strengths-based context. The Policy further indicates the enhancement of family functioning as a responsibility for all government departments and civil society organisations who need to make the family the focus of all service delivery. A very important aspect of the policy is that it suggests the creation of family forums as vehicles for services to families. Social workers are in an ideal position to facilitate these forums and processes to build and restore families.

In order to facilitate the wellbeing of families, we suggest that we start to actively create forums to engage with families, listen to families and implement strategies for strengthening families. We need to have forums and conversations with families to know what they experience, to support them in building their relationships, create contexts in which affection can be freely expressed and experienced, and roles and responsibilities clarified and new roles anvd responsibilities negotiated. We have to facilitate conversations about new alues and roles, respectful disciplinary practices and responsible parenting. And, above all, the forums should facilitate respect and unconditional acceptance of each other as unique individuals. This then refers to the responsibility on the training institutions to reconsider their training of social workers to enable them to respectfully facilitate the forums and conversations and work alongside families towards cultivating their wellbeing.

REFERENCES

ARMSTRONG, M.I., BIRNIE-LEFCOVITCH, S. & UNGAR, M.T. 2005. Pathways between social support, family well-being, quality of parenting and child resilience: what we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2):269-281. [ Links ]

BELSEY, M.A. 2005. AIDS and the family: policy options for a crisis in family capital. New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

BECVAR, D.S. & BECVAR, R.J. 2009. Family therapy: as systematic integration (7th ed). New York: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson. [ Links ]

BORSTEIN, M.H. & ZLOTNIK, D. 2009. Parenting styles and their effects. Social and Emotional Development in Infancy and Early Childhood, 496-509. [ Links ]

BOTHA, F. & BOOYSEN, F. 2013. Family functioning and life satisfaction and happiness in South African households. Social Indicators Research, 119(1): 163-182. [ Links ]

CAPRARA, G.V., PASTORELLI, C., REGALIA, C. SCABINI, E. & BANDURA, A. 2005. Impact of Adolescents' filial self-efficacy and quality of family functioning and satisfaction. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(1):71-97. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. White Paper on Families. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DIENER, E.D., EMMONS, R.A., LARSON, R.J. & GRIFFIN, S. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1):71-75. [ Links ]

EPSTEIN, N.B., BALDWIN, L.M. & BISHOP, D.S. 1983. The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2): 171-180. [ Links ]

HOCHFELD, T. 2007. Missed opportunities: conservative discourses in the draft National Family Policy of South Africa. International Social Work, 50(1):79-91. [ Links ]

HOLBORN, L. & EDDY, G. 2011. Broken families breaking youth. First steps to healing the South African family. South African Institute of Race Relations. [ Links ]

KESSLER, R.C., MCLAUGHLIN, K.A., GREEN, J.G., GRUBER, M.J., SAMPSON, N.A., ZASLAVSKY, A.M., AGUILAR-GAXIOLA, S., ALHAMZAWI, A.O., ALONSO, J., ANGERMEYER, M., BENJET, C., BROMET, E., CHATTERJI, S., DE GIROLAMA, G., DEMYTTENAERE, K., FAYYAD, J., FLORESCU, S., GAL, G., GUREJE, O., HARO, J.M., HU, C., KARAM, H.G., KAWAKAMI, N., LEE, S., LEPINE, J.P., ORMEL, J., VILLA, J.P., SAGAR, R., TSANG, R., USTUN, T.B., VASSILAV, S., VIANA, M.C. & WILLIAMS, D.R. 2010. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5):378-385. [ Links ]

KOEN, V., VAN EEDEN, C. & ROTHMANN, S. 2013. Psychosocial well-being of families in a South African: a prospective multifactorial model. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 23(3):409-108. [ Links ]

OGWO, A. 2013. Adolescent-parent relationship as perceived by younger and older adolescents. IFE PsychologIA, 21(3):224-229. [ Links ]

OWRAGI, A., YOUSLIANI, G., & ZARNAGHASH, M. 2011. The relationship between the desired disciplinary behaviour and family functioning locus of control and self- esteem among high school students in cities of Tehran province. Social and Behavioural Sciences, 30:2438-3448. [ Links ]

LOISELLE, C.G., PROFETTO-McGRATH, J., POLIT, D.F. & BECK, C.T. 2011. Canadian essentials of nursing research (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

MURDOCK, G.P. 1949. Social structure. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

NICHOLS, M. 2010. Family theory. Concepts and methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

RYAN, R.M. & DECI, E.L. 2008. Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In: JOHN, O.P., ROBINS, R.W. & PERVIN, L.A. (eds), Handbook of personality psychology: theory and research (3rd ed). New York: Guilford Press, 654-678. [ Links ]

SHOKOOHI-YEKLA, M., PARANDA, A. & AHMADI, A. 2011. Effects of teaching problem solving strategies to parents of pre-teens: a study of family relationship. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15:957-960. [ Links ]

VLIEM, S.J. 2009. Adolescent coping and family functioning in the family of a child with autism. Michigan: The University of Michigan. [ Links ]

WALKER, R. & SHEPHERD, C. 2008. Strengthening aboriginal family functioning: what works and why? Australia: Clearing House. [ Links ]

WALSH, F. 2006. Strengthening family resilience (2nd ed). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]