Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 no.2 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-503

ARTICLES

The role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly

Edelweiss Bester; Pravani Naidoo; Anja Botha

Department of Psychology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A non-experimental research design was used to investigate the role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst elderly residents (N=122) from two retirement villages in Bloemfontein. A biographical questionnaire, the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), the Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire (SWBQ), and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) were utilised. This study yielded a statistically significant relationship between mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing. Mindfulness was also a moderator in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing. These findings can inform social work interventions aimed at optimising life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly.

INTRODUCTION

The elderly are the fastest growing population worldwide (Erber, 2013:6). However, a longer life does not guarantee good health or a high quality of life (Kobylarek, 2011). Old age is typically associated with increases in both physical and psychosocial challenges, including adapting to and coping with change and loss, increased illness, vulnerability to mental disorders, cognitive decline and greater limitations in physical functioning (Erber, 2013). Such factors have been found to have negative effects on the wellbeing of elderly individuals (Diener & Chan, 2011). At the same time, it is important to note that the positive cognitive, reflective and affective qualities that these individuals have acquired with age and life experience can serve a protective function (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Phillipson, 2013; Ramirez, Ortega, Chamorro & Colmenero, 2013).

The study of positive aging is a rapidly developing area for research and practice (Vaillant, 2015). Against this backdrop, the present study aimed to investigate whether mindfulness plays a role in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst elderly individuals.

The elderly population

The World Health Organisation (WHO, 2000:9) declares the life stage of old age to include any individual aged 65 years and older. However, in the developing world, old age includes individuals who are 60 years and older (United Nations, 2013:3). Population aging in developing countries such as South Africa poses a considerable challenge for the public health and social development sectors (World Health Organization, 2011). A greater need for chronic disease treatment and frail care amongst the elderly can overburden an already overwhelmed health-care system and render it unable to stay abreast of the increased need for medical assistance (Bergman et al., 2013). Improved wellbeing may be associated with physical and psychosocial benefits for the elderly (Diener & Chan, 2011; Ramirez et al., 2013), and thereby place fewer demands on public health and social development resources.

Wellbeing

The search for wellbeing has been regarded as a fundamental goal in life since ancient times (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Studies on wellbeing stem from two differing philosophical perspectives. Aristotle defined eudaimonia as the true way of attaining wellbeing by achieving the best in oneself in alignment with deeper personal values (Deci & Ryan, 2008:4). The second perspective, hedonia, was defined by Aristippus, who declared that pleasure, enjoyment and comfort were the way to achieve wellbeing (Waterman, 2008:40). His definition has since been elaborated to include the concept of "subjective wellbeing" (Huta & Ryan, 2010:738). While the affective component of subjective wellbeing pertains to individuals' experiences of high positive emotions and low negative emotions, the cognitive component, satisfaction with life, refers to their evaluation of how satisfied or happy they are with their lives (Diener, 1984:552; Pavot & Diener, 2009:28).

Satisfaction with life

Satisfaction with life is defined as the evaluation of individuals' lives in accordance with their personal standards (Pavot & Diener, 1993:101). Therefore, satisfaction with life is determined by comparing one's ideal life circumstances with the way one perceives one's current quality of life (Lucas, Diener & Suh, 1996; Pavot & Diener, 2009:48). It entails the extent to which personal goals are met and how well one is doing in comparison to other people (Lucas et al., 1996). Thus, in making an evaluation of life satisfaction, individuals examine the aspects of their life, weigh the good against the bad, and arrive at a global evaluation of overall satisfaction (Rothmann, 2013:178).

As satisfaction with life is a conceptually unique component of subjective wellbeing, it has been suggested that the separable elements of subjective wellbeing should be studied independently (Lucas et al., 1996). The construct of 'satisfaction with life' is regarded as a more stable and reliable component of subjective wellbeing when compared to the transient nature of affectivity (Huebner, Suldo & Gilman, 2006:274). Hence, life satisfaction is often studied as an outcome in itself, because it surpasses and integrates mood states, influences behaviour and is considered to be a fundamental contributor to wellbeing (Huebner et al. , 2006).

Research indicates that life satisfaction and evaluations of wellbeing tend to increase with age in middle and older adults. For instance, a study of 122 East Slovakian adults indicated that satisfaction with life increased from age 40 to 65, and only declined when participants became aware of their impending death (Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006:442). Moreover, participants' life satisfaction persisted even when controlling for subjective health and social contacts (Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006). Furthermore, in an American telephone survey (N=340 847) overall satisfaction with life was found to decrease slightly from age 50 to 53 and then rise continually until imminent death (Stone et al., 2010:9986). Finally, a Taiwanese study of 1,040 elderly individuals showed that education, lifestyle, social activities, geographic location and levels of urbanisation were found to hold positive implications for life satisfaction (Liao, Chang & Sun, 2012:990). The above-mentioned studies highlight the importance of understanding the dynamics of life satisfaction within the context of the aging process (Erber, 2013).

Spiritual wellbeing

In what is arguably the most widely-accepted developmental theory of aging, Erikson (1959) maintains that aging individuals reflect on their lives to determine whether they have lived meaningfully. Nelson (2012) contends that this search for meaning inevitably influences the spiritual development of the elderly. Indeed, late adulthood fosters a greater awareness of both mortality and the true meaning and purpose of life (Jong, 2013). The practice of spirituality and the experience of spiritual wellbeing do not require, but can include, membership or adherence to a specific religious group or denomination (Harlow, 2010). Briefly, spirituality is able to exist in the absence of religiosity, but the opposite is not the case (Harlow, 2010:616).

Spiritual wellbeing is defined by Gomez and Fisher (2003:1976) as the quest to find connectedness, energy and transcendence in life, and to determine what makes life worth living. Moreover, spiritual wellbeing consists of personal, communal, environmental and transcendental dimensions. The personal dimension of spiritual wellbeing refers to the way in which one intra-relates to oneself with regard to one's values, meaning and purpose in life (Gomez & Fisher, 2003). Furthermore, the communal dimension pertains to the quality of personal relationships such as friends and family, whereas the environmental component deals with respect and care for nature and the physical world (Gomez & Fisher, 2003:1976). Finally, the transcendental dimension of Gomez and Fisher's (2003:1976) conceptualisation refers to a relationship with a transcendental figure or reality that can form part of an organised religion.

Spiritual wellbeing has positive implications for mental health. In a systematic review of studies on spiritual wellbeing, religious affiliation and mental health conducted between 1971 and 2012, Koenig (2012) found that spiritual wellbeing has positive effects on mental health. Results included statistically significant relationships between spiritual wellbeing and hope, optimism, wellbeing, meaning and purpose, self-esteem and a sense of control (Koenig, 2012:15). Similarly, a multinational study of adults across 57 countries found that achieving a sense of spiritual wellbeing can predict increased health, decreased disability and higher levels of happiness and satisfaction with life (Lun & Bond, 2013:312-314). Furthermore, in a study of elderly Americans aged 65 years and older (N=6,864), Skarupski, Fitchett, Evans and De Leon (2013:892) found a positive correlation between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction. Accordingly, spiritual wellbeing can have an effect on various indicators of wellbeing (Rowold, 2011) and serve as a positive resource for building life satisfaction in old age (Skarupski et al., 2013).

Like spiritual wellbeing, mindfulness aids the meaning individuals attribute to their lives and improves their ability to engage with their environment in adaptive ways (Seligman, 2012). Ultimately, a certain level of spiritual engagement is regarded as a key mechanism in mindfulness (Kristeller, 2010). When one is actively living in the present moment without judgement, contact with oneself, others, the environment and a transcendental figure is possible (Garland & Gaylord, 2009).

Mindfulness

The concept of "mindfulness" originated from Buddhist teachings and is one of five Buddhist spiritual practices, along with faith, effort, concentration and wisdom (Malinowski, 2013:386). The ability to be mindful is an inherent human capacity (Siegel, Germer & Olendzki, 2011). And, rather than separating the practitioner from personal thoughts, emotions, behaviour or experiences, the goal of being mindful entails an attempt to more fully and vividly experience those elements that comprise daily living (Siegel et al., 2011).

Langer (1989; 1992) has defined mindfulness as a process of continually drawing new and original distinctions between stimuli regardless of whether the presenting stimuli are regarded as trivial or important. Furthermore, Kabat-Zinn (2003; 2008:1) emphasises that any experience derived from internal or external stimuli is perceived, recognised and accepted without being evaluated. His understanding is echoed in Brown and Ryan's (2003:824) definition of mindfulness as responsive attention to, and awareness of, events and experiences as they occur in the present moment. Moreover, Brown and Ryan (2003) distinguish between trait mindfulness, which is believed to predict autonomous activity in daily life, and state mindfulness, which is associated with the temporary positive affect and experience of being in the present. Brown and Ryan's (2003) definition of mindfulness informs the present study, and it was trait mindfulness in particular that was measured in this study.

Features of mindfulness were highlighted in Brown and Ryan's (2003:827) seminal study of 1,250 American students and adults in which trait mindfulness was positively correlated with life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, openness to experience, attentiveness, impulsiveness and receptivity to experience. As expected, trait mindfulness was negatively correlated with self-monitoring, self-consciousness, social anxiety, depression, neuroticism and poor psychological wellbeing (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Furthermore, results of a recent study which investigated the relationship between trait mindfulness and life satisfaction in a sample of Chinese adults (N=310) between the ages of 18 and 50 years indicate that mindfulness has a significant positive relationship with life satisfaction (Kong, Wang & Zhao, 2014:169).

Research has also indicated a positive relationship between mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing. For instance, Birnie, Speca and Carlson (2010:362) measured the self-compassion, empathy and spiritual wellbeing of American adults (N=51) aged 24 to 70 years after participating in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction training. They found that the self-compassion, empathy and spiritual wellbeing of participants showed statistically significant increases as their levels of mindfulness improved. Participants' levels of personal distress, mood disturbance and symptoms of stress also decreased during the course of the study (Birnie et al., 2010:364). Thus, mindfulness has shown somewhat promising results in terms of its effects on spiritual wellbeing and the promotion of wellbeing.

Based on the above-mentioned literature, the application of the constructs of mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing to gerontology is deemed to be a worthwhile area for research within social work and the broader helping professions. In addition, there is a paucity of local and international research regarding these constructs (Nexus, Academic Search Complete and PsycINFO database searches, 28 July 2015). Accordingly, this study has investigated the role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst a sample of South African elderly individuals.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate whether mindfulness moderates the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly. In order to address the aim, the following research questions were posed:

• Is there a significant relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction amongst the elderly?

• Is there a significant relationship between mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly?

• Does mindfulness moderate the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly?

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

In order to answer the research questions, a quantitative, non-experimental study (Stangor, 2015) was conducted. In this study mindfulness was the predictor variable, while spiritual wellbeing and satisfaction with life were the outcome variables.

Data collection and participants

Prior authorisation was obtained from two retirement villages in Bloemfontein to collect data for this study on their premises. The participants (N=122) were white and Afrikaans speaking, with an average age of 73.6 years. They were mostly female (72%), aged 60 to 69 (41%), married (53%) and Christian (96%). As residents at both retirement villages are Afrikaans speaking, permission was obtained from the authors of the questionnaires to translate them into Afrikaans. The questionnaires were also printed in a large font so that participants could read them easily.

Participants were recruited by means of non-probability convenience sampling (Stangor, 2015). They were requested to either leave the questionnaires at the administration office or in their post boxes for collection at a predetermined date and time. While a total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, 125 questionnaires were returned, indicating a response rate of 27.8%. Although this is below the expected response rate of 30% and 40% for mail questionnaires (Langbein, 2012), as Phillipson (2013) reminds us, the decline in physical and cognitive abilities which is associated with aging could have had an impact on the response rate in this study.

Measures

The participants in the study completed a short biographical questionnaire and three self-report questionnaires (Stangor, 2015). The following questionnaires were included in the self-report booklet:

• A biographical questionnaire consisting of eight items: This questionnaire was compiled by the researcher in order to gather demographic information such as age, gender, race, marital status and religious orientation.

• The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) developed by Brown and Ryan (2003): This 15-item self-report scale assesses trait mindfulness, namely open or receptive awareness of, and attention to, what is taking place in the present moment (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Responses are scored on a Likert scale ranging from "almost always" (rated 1) to "almost never" (rated 6). Scale items reflect inattention across several everyday situations and domains (e.g. emotional, physical, cognitive and general). The scale was scored by computing the mean of the 15 items. An individual score can range between 15 and 90, with higher scores indicating higher levels of everyday mindfulness. Lavender, Gratz and Anderson (2012) obtained a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 in 296 male American university students. Furthermore, O'Neill Wolmarans (2013) found the internal consistency of the MAAS to be 0.91 in a sample of South African middle-aged adults. More recently, De Frias and Whyne (2015) obtained a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 in a sample of 134 American adults aged 50 to 85 years.

• The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & GRIFFIN, 1985), used to measure global cognitive judgements of participants' satisfaction with life: The SWLS is a five-item, seven-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" (rated 1) to "strongly agree" (rated 7), with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction with life. The scale's internal consistency has been measured at 0.87, and a two-month test-retest stability coefficient of 0.82 was obtained for North American undergraduate psychology students (Diener et al., 1985). Moreover, the internal consistency of the SWLS has been measured at 0.69 for adolescents of various cultural groups in the Free State province of South Africa (Van Wyk, 2010).

• The 20-item Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire (SWBQ), used to measure participants' feeling of connection to specific life components (Gomez & Fisher, 2003): The SWBQ has four subscales, namely personal, communal, environmental and transcendental scales (Gomez & Fisher, 2003). Participants have to indicate the extent to which the statements describe their experiences of the past six months, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from "very low" (rated 1) to "very high" (rated 5). The score of each subscale is determined by calculating the mean of the five items assigned to the subscale. To obtain a total score, the mean of the four subscales is calculated. A high total score indicates a high level of spiritual wellbeing. The reliability of the SWBQ was demonstrated to be 0.89 and the internal consistency was measured at 0.92 in Australian high school students (Fisher, 2010).

The alpha coefficients were calculated to determine the internal consistency of the data that were yielded by the scales and subscales for this specific sample (Table 1).

High alpha coefficients were found for all the scales and subscales. This indicates that the data obtained in the present study can be considered to be reliable, and can be used for further analyses.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State (UFS), as well as the managing director of the retirement villages in question. Written informed consent was also obtained from the elderly individuals prior to their participation. An information sheet specifying the purpose of the study and emphasising that individuals had the right to withdraw their participation without any repercussions was attached to the questionnaires. Participants were informed that certain identifying features might come forth during the biographical questionnaire but, for those who did not wish to be identified, numbers were used to protect their anonymity.

Bearing in mind that the elderly constitute a vulnerable group, the principles of non-maleficence and beneficence were upheld in an attempt to avoid harm to the participants during the research process (Allan, 2011). Should participants have reported emotional vulnerability as a result of involvement in the study, they would have been referred for psychological services rendered by Psychology Master's students at the UFS, under strict supervision of lecturers. However, no referrals were necessary.

All data obtained in the study have been kept confidentially in a locked cabinet. Computers that were used during the study were password protected. The data will be kept for a period of at least one year. The researcher will retain any records used for research purposes in case of queries or disputes. Finally, participants have been provided with detailed feedback of the results of the study in the form of a circulated letter that included the findings of the study and a detailed explanation of their meaning. The contact details of the principal researcher were also included in case the participants had any further enquiries.

Statistical procedure

The analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp, 2013). In order to investigate the role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly, a moderated multiple regression was used in analysis (Stangor, 2015). The moderator, or the interaction factor, is the product of mindfulness and life satisfaction. The dependent variable in this study was spiritual wellbeing.

To address the issue of multicollinearity as a precaution in the current study, the unstandardised scores of the independent variables were used. This was accomplished by centring both the independent variables on their respective sample means through subtracting the means of the total variable from the score. The equations for centring the two independent variables are:

• Centred scores for mindfulness = Total mindfulness score - Mean mindfulness score

• Centred scores for satisfaction with life = Total satisfaction with life score - Mean satisfaction with life score

The moderator, or interaction term, was the product of the two centred variables, identified by:

• Mindfulness score x Satisfaction with life score = Centred mindfulness score x Centred satisfaction with life score

RESULTS

A correlation matrix was used to investigate whether a statistically significant relationship exists between the dependent variable, spiritual wellbeing and the centred independent variables, as well as the moderator, mindfulness. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 indicates a significant positive correlation between mindfulness and satisfaction with life (r=0.244, p=0.007). Thus, an increase in mindfulness is associated with an increase in satisfaction with life. There was also a significant positive correlation between mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing (r=0.319, p=0.000). An increase in mindfulness can thus also be associated with an increase in spiritual wellbeing. Finally, a significant positive correlation was established between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing (r=0.577, p=0.000). Thus, for the elderly participants, an increase in satisfaction with life is associated with an increase in spiritual wellbeing.

A moderated multiple regression was conducted with spiritual wellbeing as the dependent variable. The centred variables for mindfulness and life satisfaction were entered into model 1, and the moderator, mindfulness, entered additionally into model 2. The results are presented in Table 3.

In model 1 the centred variables for mindfulness and life satisfaction were entered as independent variables. This model explains 36.7% of the variance in spiritual wellbeing (p>0.001). After entering the moderator in model 2, the total variance explained by the model is 39%. This is a statistically significant contribution as indicated by the Sig. F Change (p<0.001). Therefore, the ANOVA indicates that the model as a whole is significant (p<0.001).

The addition of the product term (Mindfulness x SWL) resulted in a significant increase in the variance explained in spiritual wellbeing [R2change=0.022; F(1.117)=4.297; p=0.040]. This indicates that mindfulness is a significant moderator of the relationship between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing in the elderly. In other words, the relationship between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing differs with different levels of mindfulness. The nature of the moderator effect will be explored further below.

In order to determine the nature of the moderator effect, a quartile analysis was conducted for the mindfulness variable. This analysis allows for determining the cut points for the top and bottom 25% of participants' mindfulness scores. Then, satisfaction with life was plotted against spiritual wellbeing, first for the top 25% of mindfulness scores, then for the middle 50% of mindfulness scores and, lastly, for the bottom 25% of mindfulness scores. The results are presented below.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing for the 25% of participants with the lowest mindfulness scores. More detail on this relationship is provided in Table 4.

Figure 1 and Table 4 clearly point to a moderate positive correlation between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing for the 25% of participants with the lowest mindfulness scores (r=0.643; p=0.00).

Figure 2 above shows the scatterplot for the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing for the participants with the highest mindfulness scores. Similarly, Table 5 indicates a moderate positive correlation (r=0.613; p=0.00) between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing for the participants with the highest mindfulness scores.

To summarise, Figures 1 and 2 are scatterplots for the correlations between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing for the 25% of participants with the lowest mindfulness scores and highest mindfulness scores. As seen in Tables 4 and 5, moderate positive correlations were found for the 25% of participants with the highest (r=0.613; p=0.00) and lowest (r=0.643; p=0.00) mindfulness scores.

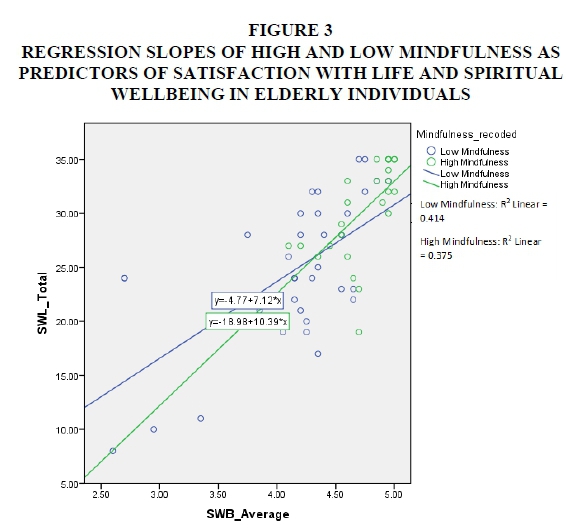

Figure 3 shows how high mindfulness and low mindfulness predict satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing in elderly individuals. The regression slopes (b) indicate that the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction is steeper for the group of participants with high mindfulness (b=10.39), than it is for individuals with low mindfulness (b=7.12).

To summarise, a moderated multiple regression was conducted to assess whether mindfulness significantly moderates the relationship between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing in elderly individuals. The results indicated that there was a statistically significant moderator effect of mindfulness, as evidenced by the addition of the interaction term, explaining an additional 2.2% of the total variance (p=0.04). Further inspection of the moderator effect revealed that the slope of the relationship between satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing for the 25% of participants with the lowest mindfulness scores (b=7.12) is not as steep as for the 25% of participants with the highest mindfulness scores (b=10.39). This means that high mindfulness scores are a stronger predictor of the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction than low mindfulness in the current sample of elderly individuals.

DISCUSSION

The scores on the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the Satisfaction with Life Scale correlated significantly with one another. This result answers the first research question by indicating that the more aware the elderly participants were of their internal and external environments, the higher their evaluations of their lives were. It is relevant to note that individuals have different standards for what comprises the good life (Diener et al., 1985; Pavot & Diener, 1993); hence, greater life satisfaction can co-exist with a stronger desire to live in the moment and delight in the fact that one's life corresponds with one's personal criteria for what "the good life" implies. Furthermore, the correlations that were found in this study correspond with results from earlier studies. For instance, Brown and Ryan (2003:827) found that increased mindfulness was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction in a sample of American students and adults (N=1,250). Moreover, in a study of American undergraduate college students (N=365), mindfulness was shown to have a positive relationship with life satisfaction (Christopher & Gilbert, 2010). More recently, Kong et al. (2014) also found a positive relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction in a sample of Chinese adults (N=310). Therefore, it can be inferred that the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction appears to present similarly for different age and cultural groups.

Erikson (1959) described the crisis of old age as ego integrity versus despair. This indicates that individuals reflect on their lives as they enter the final stage of their psychosocial development (Erikson, 1959). Christopher and Gilbert (2010:17) maintain that successful resolution of the ego integrity versus despair crisis can lead to higher self-esteem which, in turn, would lead to higher levels of life satisfaction. In this regard, Kong et al. (2014:169) found that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness also had higher core self-evaluations, which increased their satisfaction with life. This could explain why life satisfaction has been shown to improve in later life (Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006; Stone et al., 2010).

Scores on the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire correlated significantly with one another. This indicates that participants who viewed their inner experiences without judgement also experienced better relationships with themselves, others, the environment and a transcendental figure. This finding answers the second research question, and is supported by results of similar studies. For instance, in research conducted by Garland and Gaylord (2009:4), participants who received mindfulness training experienced higher levels of spiritual wellbeing (N=60) in comparison to participants who received other interventions. In the same vein, research by Birnie et al. (2010:364) demonstrated that improved mindfulness led to inherent increases in spiritual wellbeing in a sample (N=51) of American adults. Furthermore, in their recent study of mindfulness in cancer patients Labelle et al. (2015:159-161) contended that attending to all aspects of present-moment experience with acceptance may allow individuals to see what is most important in their lives more clearly. Accordingly, it is worth noting that mindfulness does not exist in the absence of spirituality and cannot be divorced from its fundamental spiritual roots (Falb & Pargament, 2012).

Development is influenced by both culture and biology (Phillipson, 2013). As biological abilities decline with age, cultural supports such as education and relationships are strengthened and can act as compensatory factors. Most of the participants in the current study indicated that they were religious and belonged to a church denomination. Also, it is relevant to note that, as individuals age, they become more aware of their mortality and are reminded regularly of this truth by their declining physical abilities (Nelson, 2012). Therefore, it is possible that the elderly participants in this study could have been counteracting biological decline by relying on cultural activities such as religious practices. Religious practices would, in turn, promote their spiritual wellbeing (Rowold, 2011). With improved spiritual wellbeing and an awareness that life is fleeting, it is plausible that the elderly participants could be experiencing greater mindfulness as a way of engaging as fully as possible with the limited time that they have left.

With regard to the third research question, the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction in the group with the highest levels of mindfulness exhibited a steeper slope (b=10.39) than for the group with the lowest levels of mindfulness (b=7.12). To account for this result, it is vital to consider Brown and Ryan's (2003) finding that high levels of mindfulness correlate with personality traits such as emotional intelligence, openness to experience, receptiveness and attentiveness. In the present study it is plausible that the presence of similar personality traits could have encouraged the elderly participants to be more mindful of their criteria for the good life and of their relationships with themselves, others, the environment and a transcendental figure. In turn, this could have allowed them to be acutely aware of their circumstances and actively pursue their idea of true meaning and the good life. Furthermore, Brown and Ryan's (2003) study demonstrated that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness are less vulnerable to the temptation to present themselves in a favourable light. The reason for this could be the reduction in self-consciousness that is associated with high levels of mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003:830).

As with high levels of mindfulness, it is possible that variables which had not been measured in this study had an impact on the role of mindfulness in the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing. For instance, Brown and Ryan (2003:825) found that social anxiety, self-consciousness, dishonesty and neuroticism correlate negatively with mindfulness. This could indicate that individuals with low levels of mindfulness are more vulnerable to the social desirability bias (Roodt, 2013) than individuals with high levels of mindfulness. The reason that these individuals scored low on mindfulness - although a steep slope for the relationship between their life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing was indicated - might be ascribed to the way in which the MAAS is worded. The statements in the MAAS are worded indirectly because Brown and Ryan (2003:823) aimed to control for the social desirability bias based on their belief that mindlessness is more common than mindfulness.

Another possible explanation for the positive slope of the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing in the participants with the lowest levels of mindfulness is that, although many of the participants in the study exhibited exceptional vigour and heartiness for still being able to live independently, this does not mean that they have been completely immune to the aging process. Impairments in immediate memory are expected in normal aging (Phillipson, 2013) and can have a negative impact on mindfulness. Such expected declines in immediate memory would reflect negatively in the MAAS on items such as "I find it difficult to stay focused on what's happening in the present" and "I forget a person's name almost as soon as I've been told it for the first time". Also, many of the participants who are of an advanced age might not have responded accurately to the item "I drive to places on 'automatic pilot' and then wonder why I went there". This could account for the fact that the potential loss of abilities which contribute to mindfulness could be compensated for by improved satisfaction with life (Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006) and spiritual wellbeing (Nelson, 2012). This concurs with the lifespan developmental theory principle that, as individuals might be regressing or losing functioning in one area, they might experience improvement in another (Baltes & Baltes, 1990).

CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to investigate whether mindfulness moderates the relationship between life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing in a sample of elderly participants in Bloemfontein, South Africa. The study yielded a statistically significant relationship between mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing in this group. Mindfulness was also found to be a moderator in the relationship between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction.

The results of this study have added to the existing body of research on gerontology by exploring the role of mindfulness in relation to life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing. Findings may be used to improve understanding of the manifestation of life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly within the South African context. In addition, the present study contributes to the limited knowledge regarding trait mindfulness as a naturally occurring quality in elderly individuals.

As part of the move to research and promote positive aging, results from this study can also inform social work practice with regard to the optimisation of life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing in elderly adults. Diener and Chan (2011) believe that increased life satisfaction will improve the length and quality of life of the elderly. Similarly, Nelson (2012) posits that spiritual wellbeing plays a critical role in the meaning making and general wellbeing of the elderly. In this regard, the results of this study indicate that interventions should be aimed at promoting and facilitating mindfulness in the elderly to improve their satisfaction with life and spiritual wellbeing. As mentioned earlier, more resources are required in order to care for the growing elderly population (Bergman et al., 2013). In turn, the improvement of their wellbeing could lead to better physical and mental health and alleviate the already overburdened health-care facilities in South Africa (Bergman et al., 2013; Diener & Chan, 2011; Ramirez et al., 2013). Aiming to increase mindfulness in older adults could enhance their spiritual wellbeing and overall life satisfaction. Hence, within the elderly population, being mindful could lead to improvements in health and wellbeing.

The study had some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants from two retirement villages in Bloemfontein. Individuals living outside of retirement villages, and of different socioeconomic statuses, were not included. Also, males were underrepresented in this study, as were black, Indian and coloured elderly adults. Accordingly, the results cannot be generalised to the entire South African elderly population. Moreover, the scale used to measure mindfulness might not be suitable for use among the elderly, as some of the statements used to measure the construct are no longer applicable to this group. The measurement of mindfulness in the elderly might differ from other age groups; thus, the revision of measurement scales for the elderly population is recommended. Furthermore, the sample size (N=122) was fairly small and consisted mostly of white, Afrikaans-speaking, educated and widowed females. The influence of gender, race, cultural background and relationship status on mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study. In future studies samples should be more representative of South African demographics. In addition, the elderly population has been subdivided into developmental groups such as young old (60-69 years), middle-aged old (70-79 years), old old (80-89), and very old old (90+) each with its own developmental tasks (Craig & Dunn, 2010). Future studies could take into account the nuances in experience within each of these developmental stages. Moreover, the finding that lower scores of mindfulness predict a stronger relationship between spiritual wellbeing and life satisfaction than higher scores of mindfulness indicates that the manifestation of mindfulness in the elderly population requires further study.

In general, a more comprehensive account of the mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing of elderly participants is needed. Accordingly, it is recommended that future studies should include data-gathering methods other than self-report measures. Indeed, future studies could adopt a mixed methods approach by including qualitative approaches to inquiry, such as semi-structured interviews and focus groups, to assist participants in portraying and elaborating on their experiences in depth (Silverman, 2013). This use of a mixed methods approach will allow increased generalisability of results because knowledge would be created with greater depth and clarity than either qualitative or quantitative methods can provide alone (Stangor, 2015). Such an approach will also allow the investigation of the affective component of subjective wellbeing and state mindfulness as well, which would yield a broader picture of wellbeing and mindfulness amongst the elderly. Moreover, future longitudinal studies could provide insight into the possible changes in the relationships between mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing across the lifespan.

Owing to population aging, it is increasingly important to understand the factors that could contribute to flourishing within the elderly population. Accordingly, those conducting future research on positive aging should prioritise the investigation and promotion of mindfulness, life satisfaction and spiritual wellbeing amongst the elderly. Such efforts would duly inform practice not only in the field of social work, but within the broader helping professions as well.

REFERENCES

ALLAN, A. 2011. Law and ethics in psychology: an international perspective (2nd ed). Somerset West: Inter-Ed Publications. [ Links ]

BALTES, P.B. & BALTES, M.M. 1990. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In: BALTES, P.B. & BALTES, M.M. (eds) Successful aging: perspectives from the behavioral sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

BERGMAN, H., KARUNANANTHAN, S., ROBLEDO, L.M.G., BRODSKY, J., CHAN, P., CHEUNG, M. & BOVET, P. 2013. Understanding and meeting the needs of the older population: a global challenge. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 16(2):61-65. [Online] Available: http://www.cgjonline.ca [Accessed: 21/01/2014]. [ Links ]

BIRNIE, K., SPECA, M. & CARLSON, L.E. 2010. Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26(5):359-371. [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com [Accessed: 05/05/2014]. [ Links ]

BROWN, K.W. & RYAN, R.M. 2003. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84:822-848. [Online] Available: http://www.apa.org [Accessed: 02/06/2014]. [ Links ]

CHRISTOPHER, M. & GILBERT, B. 2010. Incremental validity of components of mindfulness in the prediction of satisfaction with life and depression. Current Psychology, 29(1):10-23. [Online] Available: http://www.springer.com [Accessed: 27/03/2014]. [ Links ]

CRAIG, G.J. & DUNN, W.L. 2010. Understanding human development (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

DECI, E.L. & RYAN, R.M. 2008. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and wellbeing: an introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1):1-11. [Online] Available: www.springer.com [Accessed: 06/11/2013]. [ Links ]

DE FRIAS, C.M. & WHYNE, E. 2015. Stress on health-related quality of life in older adults: The protective nature of mindfulness. Aging and Mental Health, 19(3):201-206. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 27/05/2015]. [ Links ]

DIENER, E. 1984. Subjective wellbeing. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3):542-575. [Online] Available: http://www.internal.psychology.illinois.edu [Accessed: 06/11/2013]. [ Links ]

DIENER, E. & CHAN, M.Y. 2011. Happy people live longer: subjective wellbeing contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Wellbeing, 3(1):1-43. [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com [Accessed: 06/11/2013]. [ Links ]

DIENER, E., EMMONS, R.A., LARSEN, R.J. & GRIFFIN, S. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49:71-75. [Online] Available: www.tandfonoline.com [Accessed: 05/11/2013]. [ Links ]

DZUKA, J. & DALBERT, C. 2006. The belief in a just world's impact on subjective wellbeing in old age. Aging and Mental Health, 10(5):439-444. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 13/11/2013]. [ Links ]

ERBER, J.T. 2013. Aging and older adulthood. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

ERIKSON, E.H. 1959. Identity and the life cycle. New York: International University Press. [ Links ]

FALB, M.D. & PARGAMENT, K.I. 2012. Relational mindfulness, spirituality and the therapeutic bond. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 5(4):351-324. [Online] Available: http://asianiournalofpsychiatry.com [Accessed: 02/02/2014]. [ Links ]

FISHER, J. 2010. Development and application of a spiritual wellbeing questionnaire called SHALOM. Religions, 1:105-121. [Online] Available:http://www.mdpi.com [Accessed: 21/10/2013]. [ Links ]

GARLAND, E. & GAYLORD, S. 2009. Envisioning a future contemplative science of mindfulness: Fruitful methods and new content for the next wave of research. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14(1):3-9. [Online] Available: http://www.sagepub.com [Accessed: 22/07/2014]. [ Links ]

GOMEZ, R. & FISHER, J. W. 2003. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences 35:1975-1991. [Online] Available: http://researchonline.ballarat.edu.au [Accessed: 21/10/2013]. [ Links ]

HARLOW, R. 2010. Developing a spirituality strategy - why, how, and so what? Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13(6):615-624. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 13/05/2014]. [ Links ]

HUEBNER, E.S., SULDO, S.M. & GILMAN, R. 2006. Life satisfaction. In: BEAR, G.C. & MINKE, K.M. (eds) Children's needs: III. Development, prevention and intervention. Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists. [ Links ]

HUTA, V. & RYAN, R.M. 2010. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: the differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6):735-762. [Online] Available: http://www.springer.com [Accessed: 02/02/2014]. [ Links ]

IBM CORP. 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [ Links ]

JONG, H.W. 2013. Mindfulness and spirituality as predictors of personal maturity beyond the influence of personality traits. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(1):38-57. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 13/08/2014]. [ Links ]

KABAT-ZINN, J. 2003. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2):144-156. [Online] Available: http://www.onlinelibrarywiley.com [Accessed: 13/08/2014]. [ Links ]

KABAT-ZINN, J. 2008. Arriving at your own door. London: Piatkus Books. [ Links ]

KOBYLAREK, A. (ed) 2011. Aging: Social, biological and psychological dimensions. Wroclaw: Agenca Wydawnicza. [ Links ]

KOENIG, H.G. 2012. Religion, spirituality and health: the research and clinical implications. International Scholarly Research Notices Psychiatry, 1-33. [Online] Available: http://www.hindawi.com [Accessed: 01/09/2014]. [ Links ]

KONG, F., WANG, X. & ZHAO, J. 2014. Dispositional mindfulness and life satisfaction: the role of core self-evaluations. Personality and Individual Differences, 56:165-169. [Online] Available: http://www.elsevier.com [Accessed: 02/10/2014]. [ Links ]

KRISTELLER, J. 2010. Spiritual engagement as a mechanism of change in mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapies. In: BAER, R.A. (ed), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications. [ Links ]

LABELLE, L.E., LAWLOR-SAVAGE, L., CAMPBELL, T.S., FARIS, P. & CARLSON, L.E. 2015. Does self-report mindfulness mediate the effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on spirituality and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(2):153-166. [Online] Available: www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 02/10/2014]. [ Links ]

LANGBEIN, L.I. 2012. Public program evaluation: a statistical guide. New York: M.E. Sharpe. [ Links ]

LANGER, E.J. 1989. Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

LANGER, E.J. 1992. Matters of mind: mindfulness/mindlessness in perspective. Consciousness and Cognition, 1:289-305. [Online] Available: http: //www.instituteofcoaching.org [Accessed: 15/03/2014]. [ Links ]

LAVENDER, J.M., GRATZ, K.L. & ANDERSON, D.A. 2012. Mindfulness, body image and drive for muscularity in men. Body Image, 9(2):289-292. [Online] Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com [Accessed: 13/05/2014]. [ Links ]

LIAO, P., CHANG, H. & SUN, L. 2012. National Health Insurance program and life satisfaction of the elderly. Aging and Mental Health, 16(8):983-992. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com. [Accessed: 02/02/2014]. [ Links ]

LUCAS, R.E., DIENER, E. & SUH, E.M. 1996. Discriminant validity of wellbeing measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84:616-628. [Online] Available: http://www.apa.org [Accessed 19/04/2014]. [ Links ]

LUN, V.M. & BOND, M.H. 2013. Examining the relation of religion and spirituality to subjective well-being across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(4):304-315. [Online] Available: http://www.apa.org [Accessed 22/10/2013]. [ Links ]

MALINOWSKI, P. 2013. Flourishing through meditation and mindfulness. In: DAVID, S.A., BONIWELL, I. & AYERS, C.A. (eds) The Oxford handbook of happiness. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

NELSON, J.M. 2012. Psychology, religion and spirituality. New York: Springer Science and Business Media. [ Links ]

O'NEILL WOLMARANS, B. 2013. The role of mindfulness in the psychological wellbeing and life satisfaction of adults. University of the Free State, (MA Thesis) [ Links ]

PAVOT, W. & DIENER, E. 1993. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment 5(2):164-172. [Online] Available: http://www.apa.org [Accessed: 21/10/2013]. [ Links ]

PAVOT, W. & DIENER, E. 2009. Progress and opportunities. In: PAVOT, W. & DIENER, E. (eds) Assessing well-being: the collected works of Ed Diener. London: Springer Science and Business Media. [ Links ]

PHILLIPSON, C. 2013. Ageing. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

RAMIREZ, E., ORTEGA, A.R., CHAMORRO, A. & COLMENERO, J.M. 2013. A program of positive intervention in the elderly: memories, gratitude and forgiveness. Aging and Mental Health. [Online Epub ahead of print]. Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 21/10/2013]. [ Links ]

ROODT, G. 2013. Basic measures and scaling concepts. In: FOXCROFT, C. & ROODT, G. (eds) Introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context (4th ed). South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

ROTHMANN, S. 2013. Measuring happiness: results from a cross-national study. In: WISSING, M.P. (eds.) Well-being research in South Africa. Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media. [ Links ]

ROWOLD, J. 2011. Effects of spiritual well-being on subsequent happiness, psychological well-being, and stress. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(4):950-963. [Online] Available: http://www.springer.com [Accessed: 13/10/2013]. [ Links ]

RYAN, R.M. & DECI, E.L. 2001. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Annual Review of Psychology, 52:141166. [Online] Available: www.annualreviews.org [Accessed: 30/09/2013]. [ Links ]

SELIGMAN, M.E.P. 2012. Flourish. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

SIEGEL, R.D., GERMER, C.K. & OLENDZKI, A. 2011. Mindfulness: what is it? Where does it come from? In: DIDONNA, F. (ed), Clinical handbook of mindfulness. New York: Springer Science + Business Media. [ Links ]

SILVERMAN, D. 2013. Doing qualitative research (4th ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

SKARUPSKI, K.A., FITCHETT, G., EVANS, D.A. & DE LEON, C. 2013. Race differences in the association of spiritual experiences and life satisfaction in older age. Aging and Mental Health, 17(7):888-895. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 22/05/2014]. [ Links ]

STANGOR, C. 2015. Research methods for the behavioural sciences (5th ed). Belmont: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

STONE, A.A., SCHWARTZ, J.E., BRODERICK, J.E. & DEATON, A. 2010. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 107:9985-9990. [Online] Available: http://www.springer.com [Accessed: 21/09/2013]. [ Links ]

VAN WYK, H. 2010. Die verband tussen weerbaarheidsfaktore en lewenstevredenheid by adolessente: 'n kruiskulturelestudie. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State, (MA Thesis) UNITED NATIONS. 2013. World Population Ageing 2013. [Online] Available: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/ WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf [Accessed: 21/09/2013]. [ Links ]

VAILLANT, G.E. 2015. Positive aging. In: JOSEPH, S. (ed), Positive Psychology in practice: promoting human flourishing in work, health, education and everyday life (2nd ed). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

WATERMAN, A.S. 2008. Reconsidering happiness: a eudaimonist's perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4):234-252. [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com [Accessed: 18/05/2014]. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2000. Information needs for research, policy, and action on ageing and older adults. Bethesda: US National Institute on Ageing. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION. 2011. Global health and ageing. Bethesda: US National Institute on Ageing. [ Links ]