Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 no.2 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-501

ARTICLES

The design of a protocol for assessing prospective foster parents in South Africa

Juliet CarterI; Adrian van BredaII

IPostgraduate student, Department of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. advanbreda@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the development of a contextually appropriate protocol in social work for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa. The protocol was designed in two stages using Thomas's developmental research process and participatory action research methodologies. First, we designed a model of the competencies of effective foster families (determining "what" constitutes a good foster parent and developing a model of the "ideal" foster parents). Second, we designed and developed an assessment protocol with which to assess prospective foster families (specifying "how" one determines if foster parents meet the model's criteria of the ideal foster parents).

INTRODUCTION

Over half a million children were living in foster care in 2014 (South African Social Security Agency, 2014:1). Each of these placements had to be screened by a social worker in order to make the recommendation that these care givers would make suitable foster parents. There are, however, several concerns about these screening processes, which gave rise to this study.

From the literature review and based on anecdotal evidence, it became clear that there is no set of objective and contextually-relevant criteria for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa. The broad criteria provided in the Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005) are a good starting point for these assessments, but are open to a wide range of interpretation by assessing social workers. This is a matter of concern, given that a substantial portion of foster placements may well last for the duration of the foster child's childhood. Given the absence of a contextually appropriate protocol for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa, it seems that social workers require additional support and resources with which to assess prospective foster parents.

This study was thus conducted to provide a solution to a pressing problem in social work, specifically in foster care, that could be put to use in practice settings in South Africa. The intention was to design a social technology innovation that social workers would be able to use for the assessment of prospective foster parents. This technology has two components: a model of an "ideal" foster parent, rooted in the contextual realities of South African families; and a protocol, grounded in this model, for the assessment of prospective foster parents. The use of the model and protocol will enable social workers to carry out thorough and comprehensive assessments of the social functioning of prospective foster parents, based on sound research and theoretical foundations.

In this paper we provide a broad outline of the contextual factors that give rise to the large numbers of children requiring foster care, the legislative responses to these factors and the reasons why foster placements break down. After that we briefly map out the methodology followed to design the model and protocol for foster screening. The tools that emerged through the research are described and presented. It is our hope that these tools will be taken up for use by social workers who screen foster parents.

BACKGROUND

Among the various factors that lead to South African children being placed in foster care, the loss of parents as a result of AIDS is the most pertinent. South Africa has been gripped by the HIV pandemic, leaving thousands of orphaned and vulnerable children (OVCs) in its wake (Department of Social Development, n.d.b; Desmond & Kvalsvig, 2005; Mkhize, 2006; Thiele, 2005).

In 2013 18% of the total number of people with HIV globally were living in South Africa - the highest rate in the world (United Nations, 2014). In the same year South Africa accounted for 13% of the total number of AIDS-related deaths globally (United Nations, 2014).

South Africa remains challenged to find viable solutions to the OVC crisis. The reality of the South African context (as well as of many Sub-Saharan countries) is that many of the safety nets that were traditionally in place to safeguard the wellbeing of children are being eroded by HIV and AIDS (Carter, 2004). Freeman and Nkomo (2006) and Hunter and Williamson (2000, 2002) point out that as the pandemic takes hold, the services and structures that exist to provide a safety net for vulnerable children will become increasingly strained and overwhelmed. This includes the extra strain placed on the extended family to take care of orphaned or vulnerable child relatives. Children's basic rights appear to be at an increased risk of being violated.

OVCs require, and are entitled to, suitable alternative care arrangements. Children have the right to be raised in a family. This right is enshrined in the South African Constitution (1996, Section 28(1)), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989, Article 5) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (African Union, 1999, Articles 18-2). Furthermore, the same documents state that children requiring out-of-home care have the right to appropriate alternative care (African Union, 1999, Articles 24-25; Constitution of the RSA, 1996, Section 28(1)b; United Nations, 1989, Articles 20(1), (2), (3) and 25).

Foster care is one of the alternative care options in the continuum of care. The continuum of care ranges from the child's own family to institutionalised care (Desmond & Kvalsvig, 2005). Foster care offers a vulnerable child the chance to be cared for in a family environment, often in the child's community of origin. This is in line with the "Best Interests of the Child" as set out in Section 7(l) of the Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005, as amended).

Foster placements account for over half a million children in alternative care in South Africa. There were 530 357 children in foster care in South Africa in May 2014, based on the number of foster care grants paid to foster children during that period (South African Social Security Agency, 2014:1). Thus, given the number of children directly affected by foster care, the issue of how foster parents are assessed is highly relevant to social work practice.

In the current South African context many foster placements seem to be developing into long-term placements. By virtue of the fact that many of the children are orphans, mostly because of the HIV pandemic, it is not possible to place orphaned children back in the care of their parents. The Children's Institute maintains that in 2011 there were over one million orphans living with relatives in poverty; 460 000 of these children were reported to be in foster care placements with relatives. More than half a million orphaned children still did not have access to the Foster Child Grant as a consequence of the increased burden on social workers and a severe backlog of cases (Centre for Child Law, 2013).

As a result of the depletion of the capacity of extended families to adequately care for the children of deceased or incapacitated relatives, many children have to be placed outside of the kinship care networks. There is thus an increase in the need for long-term foster placements outside of the family of origin too. Social work services to the community, in particular rural communities, are already stretched. It thus appears that adequate screening of prospective foster parents does not take place, which can negatively impact on the wellbeing of OVCs (Freeman & Nkomo, 2006; Thiele, 2005).

When a foster placement is inadequately assessed (whether for family-related foster care or unrelated foster care), there is an increased likelihood that that placement can break down, which is detrimental to the child's wellbeing. There are various reasons cited for such breakdowns, including the movement of the foster child into adolescence; the complexity of the child's social problems; a lack of foster parent support; the incorrect matching of a child to the foster parent; interference from the biological family; overburdening of social service systems; and inadequate screening of foster parents (Booysen, 2006; Dickerson & Allen, 2007; Louw & Joubert, 2007; Mkhize, 2006).

Among the various reasons for the inadequate screening of foster parents by social workers is the lack of knowledge of social workers on how to assess prospective foster parents. Literature in the United States of America reports a concern that social workers often do not know how to assess prospective foster families (Dickerson & Allen, 2007; Louw & Joubert, 2007). Most universities in South Africa address foster care in a section of a semester module on the continuum of care (according to verbal reports from discussions with heads of seven social work departments at South African universities, or lecturers there, from 2008 to 2014). Given the scope of the continuum of care, foster care is touched on only briefly. Given the complexities of foster care, it appears that current social work students are not adequately prepared by universities to deal with foster care in the field.

The national Department of Social Development developed new foster care guidelines, "Guidelines for the Effective Management of Foster Care in South Africa" (Department of Social Development, n.d.a). While these are a helpful contribution, the guidelines do not explain how to assess a prospective foster parent. They simply provide a detailed explanation of the statutory process of foster care in South Africa. Thus social workers screen foster parents without clear guidelines from the government, compounding the lack of training received at university.

Another reason for foster placement breakdown appears to be that social workers do not feel it is necessary to subject relatives to the same rigorous screening procedure that they impose on non-related foster applicants. The literature suggests, however, that foster placements with relatives are not always in the child's best interests. Louw and Joubert (2007) conducted a study on the experiences of adolescents orphaned by AIDS. They maintain that family members are not always suitable for consideration as foster parents and therefore advocate for improved foster parent assessment.

Van der Riet (2009) and Kganyago (2006) express concern regarding the high rate of placement breakdown in South Africa, particularly in non-related foster placements.

Social workers in the field with whom we have had contact express similar concerns over the placement breakdowns in their case loads. They express the hope that having adequate skills and knowledge regarding the assessment of prospective parents may stabilise future foster placements.

Sinclair and Wilson (2003:883) state that "good foster carers are not produced by good organisation or strategic plans... [but] through accurate selection ... appropriate training, appropriate support, and, in the hopefully rare cases where this is necessary, 'counselling out'". Other literature points similarly to three primary factors that appear to have a positive impact on foster placement stability, viz. effective screening/assessment of prospective foster parents (Harlow, 2011; Louw & Joubert, 2007; Van der Riet, 2009;); adequate training of prospective foster parents (Durand, 2007; Van der Riet, 2009; Department of Social Development, n.d.a); and foster placement support (Booysen, 2006; Department of Social Development, n.d.a; Durand, 2007; Harlow, 2011; Kganyago, 2006; Mkhize, 2006; Thiele, 2005).

In addition to the above, social workers have a responsibility to thoroughly assess prospective foster parents. There are several reasons for this, including foster care orders may be extended for more than two years (Section 186 of the Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005, as amended); it is a legal mandate for social workers (Sections 46 (1)(a)(i) and 156(1)(9)(e) of the Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005, as amended); effective assessment enhances placement stability; it is an ethical obligation (Give a Child a Family, 2012: 20-23); to adhere to the values and principles of foster care in South Africa (Department of Social Development, n.d.a:13-14); to connect a child with safe and nurturing family relationships intended to last a lifetime (Section 181(b) of the Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005, as amended); and to determine a foster carer's capacity to cope with the "extra" (foster-)parenting demands (Orme, Cuddeback, Buehler, Cox & Le Prohn, 2003:11).

In the light of the above, it is evident that a contextually appropriate protocol for social work in the assessment of prospective foster parents is a great need in the field of foster care in South Africa. Consequently, the research goal of the study was to design and develop a contextually appropriate protocol in social work for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa.

METHODOLOGY

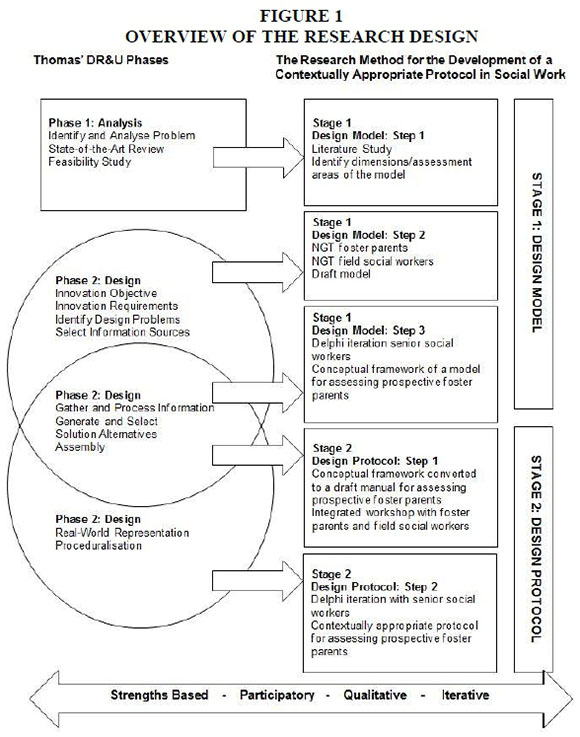

The overall design for the study was developmental research, and more specifically the Developmental Research and Utilization model (DR&U) as developed by Thomas (1984) for the design of an innovative social technology (social work innovation). Developmental research is concerned with the development of "social technology [which] is a primary means by which social work and social welfare accomplish their objectives" (Thomas 1992:72). It consists "of those methods by which the social technology of human service is analysed, designed, created and evaluated" (Thomas, 1984:23). Thomas's DR&U model (1984) is comprised of six phases, viz. analysis, design, development, evaluation, diffusion and adoption. The research method that was designed for the study was based on the first two and last two phases of the DR&U.

The study was guided by four main approaches, viz. the strengths-based, participatory, qualitative and iterative approaches.

Strengths-based approach. The primary reason for engaging with this study was to come up with a solution for social workers in the field, and not simply to add to the volume of literature on the topic of failed foster placements. The strengths-based approach to social work practice is not specifically a research approach, but an approach to social work practice in general (Poulin, 2005). The development of the protocol was based on the work of Saleebey (2002). The six principles of the strengths-based approach shift the focus of the social worker from a negative, diagnostic manner of working with people to an empowering and collaborative approach to working with people. This study adopted a strengths-based approach to open the researchers to learning from the indigenous knowledge and skills of the foster parents and social workers in the field of foster care. The study aimed to delve into these untapped reservoirs of values, skills and knowledge.

Participatory approach. Thomas (1984:165) highlighted the importance and value of user participation in the design of a social technology innovation. Users could be the social workers (who might use the social technology innovation in future screening of prospective foster parents), the foster parents (clients, who will be assessed with the innovation), and supervisors (who provide guidance and training to social workers in the field of foster care). User participation increases the likelihood of accepting the innovation and contributing to a more contextually appropriate innovation.

Qualitative approach. A qualitative approach to research "elicits participant accounts of meaning, experience or perceptions. It produces descriptive data in the participant's own words" (Fouche & De Vos, 2008:74). For this reason it is best suited for use with strengths-based and participative research approaches. The study used the qualitative approach to the research problem, as the objective of the study could not be measured on a quantitative basis. The input of the foster parents and social workers were an invaluable source of data for this study. Their contributions were an expression of their attitudes and understanding of what they thought made for a good foster parent.

Iterative approach. The research method that was designed for the study was by its very nature iterative (repetitive). The design of the model (of the ideal foster parent) and the design of the contextually appropriate protocol (with which to assess prospective foster parents) went through numerous revisions throughout the process. Thomas (1984:165) speaks of "a series of successive approximations with revisions and extensions" in the design phase of the development of an innovative social technology. The Nominal Group Techniques (NGTs) and the Delphi technique (Delbecq, Van de Ven & Gustafen, 1975) used in the data collection contributed to the iterative nature and approach of the study.

In the light of the above, a two-stage research process was designed, each comprising multiple sub-stages:

• Stage 1: Design model. An extensive literature review lead to the design of a concept model of the "ideal" foster parent. NGTs and Delphi techniques were then used with purposively selected samples of seven foster parents (judged by their supervising social workers to be experienced, reliable and competent foster parents), eight social service practitioners experienced in the foster care field (including social workers, social auxiliary workers, and child and youth care workers) and nine key informants (university lecturers, heads of social work departments, CEOs of national organisations and social work managers, all with substantial knowledge and expertise in foster care). Through these, a conceptual framework for a model of prospective foster parents was designed.

• Stage 2: Design protocol. A series of workshops and Delphi techniques with the same participants was used to translate the model into a contextually appropriate protocol for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa.

The research methodology for the study is visually represented in Figure 1.

A MODEL OF THE IDEAL FOSTER PARENT: STAGE 1 Stage 1: Step 1: Literature study

This activity proceeded from the extensive literature review (Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005, as amended; Dickerson & Allen, 2007; Harlow, 2011; International Foster Care Organisation, 2010; Orme et al., 2003; Orme, Cox, Rhodes, Coakley, Cuddeback & Buehler, 2004; Queensland Government Department of Child Safety, 2005; United Nations, 2009). A broad theoretical framework of the dimensions/assessment areas for the model of an ideal foster parent was established. Four key themes emerged from the literature study were that foster homes were able to provide:

• Unconditional love;

• Safety and security;

• Stability;

• Nurturing.

The four key themes were then ordered into four quadrants. After going back to the root meaning of each key theme (Soanes & Branford, 2002), a word search was conducted to find synonyms for each key theme. As a result of carrying out this word search, a rudimentary assessment framework took shape. This development was consistent with the fact that "a social science model is one that consists mainly of words" (De Vos, Fouche & Delport, 2008:36). The resulting quadrants and descriptions of the key themes are illustrated in Figure 2.

Stage 1: Step 2: Nominal group techniques

Separate NGTs were run with foster parents and social workers doing foster care screenings.

The single question posed to the foster parents was: "What makes a person a suitable (good) foster parent?" The foster parents gave little attention to the legal requirements for foster parenting or meeting the basic needs of a child. Although they ranked having a clean house as the highest in priority, this was the only item that referred to the physical care of a foster child. This contrasts with the literature, which highlights home condition, safety and environment as important aspects of assessing foster parents for their suitability (International Foster Care Organisation, 2010; Orme et al., 2004).

From the perspective of foster parents themselves, it appeared that at the heart of a good foster parent was someone who focused on the care of the foster child on an emotional and subjective level, more than just on a physical level. They were most concerned for what they could do for a foster child relationally. This is supported by the Department of Social Development (n.d.a), which emphasises the fact that foster parents should be able to maintain nurturing relationships with the foster child, and that such relationships could possibly last a lifetime. Communication with the foster child also seemed to be important, as was apparent in items such as being honest with the foster child, talking to the child and teaching the child values.

The single question posed to the social service professionals was: "What makes a person a suitable (good) foster parent?" The social service professionals contributed a far more holistic and rigorous set of items that described a good foster parent.

There were similarities in the items generated by both groups, such as communication with the child and caring for the child on an emotional and subjective level. Dickerson and Allen (2007:143) are of the view that nurturing as an indicator is essential for prospective foster parents, as "of all the qualities that are essential to be good foster and adoptive parents it is probably the capacity to nurture or "mother" that is most important, for it sets the tone for everything else that happens in the family".

The social service professionals however, also focused on broader issues, such as legislative requirements and the role of the foster parent outside of the home. Legislative requirements included the foster parent's name not appearing on Part B of the National Child Protection Register and child participation (which is a principle of the Children's Act (No. 38 of 2005, as amended)). In addition, items such as being a good team player and being an advocate for the foster child speak to the role of the foster parent as a member of a multidisciplinary team (International Foster Care Organisation, 2010; Orme et al., 2003).

Drawing on the literature review and the results of the NGTs with foster parents and social workers, we drafted a model of an ideal foster parent, as illustrated in Figure 3. The conceptual innovation had to be "assembled into a meaningful and sensible conceptual document that speaks to the achievement of the innovation objective" (Thomas, 1984:162). A model is defined as "something that is used as an example or an excellent example of a copy" (Soanes & Branford, 2002:578). Stockburger (1996) and De Vos et al. (2008) argue that we use models to make sense of the world around us. This is in order to understand a complex problem and to simplify the problem into manageable parts. We are then, hopefully, able to predict certain aspects of the world with slightly more clarity than we initially had, with the purpose of solving or alleviating the problem.

The model depicted in Figure 3 is an attempt to simplify (without losing sight of the complexity of the problem) what criteria could be predictors of an ideal foster parent. The model is purely a representation (De Vos et al., 2008; Stockburger, 1996) of an ideal foster parent and cannot possibly be an exhaustive list of every aspect of a prospective foster parent's life. "The value of this simplification is that it draws the attention of the researcher to specific themes" (De Vos et al., 2008:36). To reiterate, the keys themes that emerged from this study were that the ideal foster parent should be able to provide homes and care to foster children that are characterised by unconditional love, safety and security, stability and nurturing.

This model of an ideal foster parent is the summative outcome of the integration of the literature review, the foster parents' input, as well as the social service professions' contributions. The model of the ideal foster was then incorporated into a comprehensive document - "A social work model for assessing prospective foster parents" - a further outcome of the first two steps of Stage 1 of the study.

Stage 1: Step 3: Delphi technique with key informants

One iteration of the Delphi technique took place with key informants. The informants were requested to review and revise the draft model via email. Three of the nine informants participated. Feedback received from the informants was positive, with minimal editorial changes or suggestions to the model. Although we planned multiple iterations of the Delphi, we decided not to repeat a further iteration at this stage, since there were only minor editorial changes and suggestions made to the model.

These changes were incorporated into the model. All changes were tracked and the original draft model was archived for future reference if required. Thus, by the end of stage 1 of the study, we had a contextually appropriate model of a good foster parent, based on international and local literature and multiple inputs from foster parents, social workers and key informants.

The assessment of prospective foster parents is essentially an extensive information-gathering exercise and evaluation of the ability and suitability of the prospective foster parent to provide safe, stable, loving and nurturing environments for foster children (Give a Child a Family, 2012). The evaluation should take place against a set of objective criteria. This means that the assessing social worker should holistically and comprehensively assess the prospective foster parents against the set of criteria for ideal or effective foster parents. The model is a representation of the criteria that social workers could use when they are assessing prospective foster parents. It is contextually relevant to social workers in South Africa, as it has been designed with input from active foster parents, social workers and senior social workers in the field. The model is written in simple English, in continuous prose. It is a user-friendly document for practical application in a social work setting.

A PROTOCOL FOR ASSESSING PROSPECTIVE FOSTER CARE APPLICANTS: STAGE 2

Stage 1 of the research method culminated in a model of an ideal foster parent. The model outlines the criteria that a social worker should assess when making a decision about the prospective foster parent's suitability to foster a child. This section details the results of the design of the contextually appropriate protocol for the assessment of prospective foster parents in South Africa, Stage 2 of the research method.

Stage 2: Step 1: Design and workshop an assessment protocol

We drafted a protocol for assessing prospective foster parents by means of integrating the data collected in Stage 1 of this study with information from the literature and national and international laws and guidelines. The model designed in the preceding stage was used as the basis from which to assess a prospective foster parent. The purpose of drafting the protocol was to assemble the information and solutions gathered up to that point into a practice framework that was meaningful and sensible (Thomas, 1984:162).

The term "protocol" means a correct or official procedure. The draft protocol, however, had to be more than a set of correct procedures for a social worker to follow when assessing prospective foster parents. A social technology innovation that is an assessment method should contain procedures as well as "principles for gathering and evaluating diagnostic information about clients, families and other clientele" (Thomas, 1984:108). Procedures may typically be practice principles, guidelines and a description of the activities involved in the process (Thomas, 1984:163).

Central to the protocol is a set of assessment forms, which were designed based on the four quadrants of the model of the ideal foster parent (Figure 4). The forms are based on the assessment worksheets of Poulin (2005:154-159). Poulin (2005:137) proposes that social work agencies "adapt or develop procedures based on the type of information they need". The assessment forms are designed to facilitate the information-gathering process of assessing prospective foster parents. They correspond with the four quadrants (key themes) of the ideal foster parent. Each key assessment theme was further divided into key areas of assessment. The key areas were generated after careful analysis of the information gathered concerning the four characteristics of the ideal foster parent.

The assessment form was divided into three columns, viz. Strengths, Challenges and Action Required. For example, when assessing safety, the key area of home safety could be assessed in the following way:

• Strengths. The family have their own vegetable patch.

• Challenges. Garden is strewn with rusted debris. There is no fence. The house is next to a main intersection with continuous traffic from taxis in particular.

• Action required. Determine willingness and ability (costs) of family to fence off the garden and clear the debris. Time frame: 2 weeks from date of interview.

The forms are designed to facilitate a strengths-based approach to assessing prospective foster parents, by requiring the social worker to identify strengths associated with each of the key areas. If any concerns arose from the assessments, the third column would facilitate opportunities for addressing these specific issues, if possible. In other words, "social workers would not simply assess what prospective foster parents did not have or could not do, but rather what competencies they did have and what skills sets or competencies could potentially be developed. The purpose of this form was not to simply find a prospective foster parent unsuitable if they do not meet the criteria, but to develop them in the areas that were lacking, if this was possible" (Carter, 2012:149).

The forms are meant to be used as guidelines and are not exhaustive. They should be supplemented with other data-collection tools such as the ecomap or genogram (Hartman, 1995). They can be adapted by social workers and their agencies to suit their requirements and contexts. That being said, there still needs to be compliance with the minimum norms and standards, as well as the legislative requirements.

The final activity of the design phase of DR&U is the proceduralisation of the protocol. Thomas (1984:167) states that "proceduralisation is the process by which the desired activities of the helping process are described, explicated, and made into procedures that helping persons and others in the helping process may follow" (Thomas, 1984:167). The draft protocol, of which the assessment forms are a part, was proceduralised through the process of conceptualising the innovation and organising the information into principles, procedures and methods on how to assess prospective foster parents.

The purpose of the protocol is to provide guidelines for social service professionals (particularly social workers) in South Africa to enable the efficient and effective assessment of prospective foster parents. The protocol covers the assessment process from the point of recruitment to a final decision regarding the suitability of the applicant to foster a child. The protocol is not meant to be used as a quick tick-off checklist. It is meant to encourage discussion and engagement with the prospective foster family to determine whether or not they are suitable to foster a child. It encourages a joint decision-making process and values the right to self-determination of the prospective foster parent. "The focus of the assessment needs to be on the applicant's demonstrable knowledge, skills and abilities; as well as the applicant's ability to reflect on how their experiences, views and behaviour may impact on their ability to provide for a child in care" (Queensland Government Department of Child Safety, 2005:1).

The protocol is the summative outcome of the integration of the literature review, the foster parents' input, as well as the social service professionals' contributions. The protocol comprises the following sections:

• Acknowledgements;

• The purpose of the protocol;

• The theoretical framework of the protocol;

• Guiding social work principles;

• Important guiding documents;

• The assessment of prospective foster parents;

• Strengths-based prospective foster parent assessment form (Figure 4).

Following our preliminary design of this assessment protocol, we convened an integrated workshop with the foster parents and social service professionals who participated in the NGTs in the preceding stage. This was to further enhance the face and content validity of the model of an ideal foster parent, to contextualise the model, and to enhance the integrity of the content of the model through having the original participants review the revised model. In addition, the workshop was intended to review and revise the draft assessment protocol. Four of the original seven foster parents, six of the eight social service professionals and one additional foster parent (who is also a child and youth care worker) participated in the follow-up workshop. The suggestions and revisions were recorded and changes, which were primarily editorial, were made to the model and draft protocol.

Stage 2: Step 2: Delphi technique with key informants

The refined model and the draft of the contextually appropriate assessment protocol were circulated to the nine key informants who had been invited to participate in the first Delphi technique iteration in Stage 1. Four of them (including the three who had participated previously) provided feedback. This was to refine the innovations so that the proceduralisation could become more refined and relevant to the objective it was meant to achieve (Thomas, 1984:165). While the model focused on what to assess, the protocol was designed to assist social workers with how to assess prospective foster parents.

The feedback from the key informants on the draft protocol was saved as tracked changes on the document. A further iteration of the Delphi did not take place as planned, because there were only minor editorial changes and suggestions made to the model and draft protocol.

The innovation had now been reviewed and refined by a range of users (foster parents, practitioners and experts) to "reduce complexity, distil essentials, leave out unnecessary details, make it easier for users to make decisions, follow guidelines and carry out the desired behaviour" required by the innovation (Thomas, 1984:163). The protocol - the innovation - had now been brought into being "in the real-world form" (Thomas, 1984:163). The drafts and concept document were now a contextually appropriate social technology of assessment methods, having the support and buy-in of the participants.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations for practice

Social workers should be trained in how to assess prospective foster parents. The model and protocol are both stand-alone documents. Given the rigorous process of designing the model and protocol, it is envisaged that they may make a meaningful contribution to social workers assessing prospective foster parents in South Africa. The model and protocol have been registered as short courses with the SACSSP for CPD points, thus social workers could benefit from this training in terms of professional development.

Recommendations for policy

The Department of Social Development (n.d.a) recently released guidelines on the effective management of foster care in South Africa. The model and protocol should be incorporated into these guidelines, giving social workers clear and standardised procedures and criteria for assessing prospective foster parents.

Recommendations for research

The model and protocol should be further developed through processing the protocol through the middle two phases of the DR&U model, viz. development (field testing) and evaluation (formal evaluation of efficiency, effectiveness and customer satisfaction). The purpose of this would be to complete the DR&U research phases and present a more robust, valid and reliable protocol to social workers.

CONCLUSION

OVCs are among the most vulnerable members of society. When they come into the social welfare system for placement in foster care, therefore, they deserve the best that social welfare services have to offer. Foster care, as a form of alternative care, provides substitute parenting to vulnerable children. These foster parents must therefore be carefully screened as being able to provide good-quality care to children. Through a participative, strengths-based, iterative and qualitative research process, our research has found that the qualities required of these parents include being able to provide a home that is unconditionally loving, safe, stable and nurturing. Furthermore, we have developed a protocol comprising an assessment tool and set of procedures that will assist social workers in conducting rigorous and criteria-based assessments of prospective foster parents. Since these social technologies were developed and reviewed by foster parents, social service professionals and key informants, we have confidence that the use of this protocol will contribute to the selection of competent foster parents who are able to provide sustained and suitable care to OVCs, within the realities of South African contexts. It is our hope that both our research methods and the resulting social technologies will be of value to the field.

REFERENCES

AFRICAN UNION. 1999. African charter on the rights and welfare of the child. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union. [ Links ]

BOOYSEN, S. 2006. Exploring causal factors in foster placement breakdowns. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

CARTER, J. 2004. South Coast Hospice memory box project. AIDS Bulletin, 13(2):32-35. [ Links ]

CARTER, J. 2012. A contextually appropriate protocol in social work for the assessment of potential foster parents in South Africa. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

CENTRE FOR CHILD LAW. 2013. Over one million orphans desperately need the Foster Child Grant: Can the Department of Social Development deliver! Media release,17 April. [ Links ]

DELBECQ, A.L., VAN DE VEN, A.H. & GUSTAFSEN, D.H. 1975. Group techniques for program planning. Glenville, IL: Scott, Freeman & Co. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. n.d.a. Guidelines for the effective management of foster care in South Africa. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. n.d.b. National guidelines for social services to children infected and affected by HIV/AIDS. Pretoria, RSA: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DESMOND, C. & KVALSVIG, J. 2005. Evaluating replacement childcare arrangements: Methods for combining economic and child development outcome analyses. Pretoria, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S. 2008. Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professionals (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

DICKERSON, J.L. & ALLEN, M. 2007. Adoptive and foster parent screening: a professional guide for evaluations. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

DURAND, B.K. 2007. The support and training of foster parents. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

FOUCHE, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2008. Introduction to the research process. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHE, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S. Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professionals (3rd ed). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

FREEMAN, M. & NKOMO, N. 2006. Guardianship of orphans and vulnerable children: a survey of current and prospective South African caregivers. AIDS Care, 18(4):302-310. [ Links ]

GIVE A CHILD A FAMILY. 2012. The assessment of prospective foster parents. Margate, RSA: Give a Child a Family. [ Links ]

HARLOW, E. 2011. Foster care matters. Forest Hill, London: Whining & Birch Ltd. [ Links ]

HARTMAN, A. 1995. Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Families in Society, 76:111-222. [ Links ]

HUNTER, S. & WILLIAMSON, J. 2000. Children on the brink: executive summary: updated estimates and recommendations for intervention. Washington, DC: USAID. [ Links ]

HUNTER, S. & WILLIAMSON, J. 2002. Children on the brink: strategies to support children isolated by HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: USAID. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL FOSTER CARE ORGANISATION. 2010. Guidelines for foster care: Addenda. [Online] Available: http://www.crin.org/docs/Guidelines%20for%20Foster%20Care%20Addenda.doc. [ Links ]

JOINT UNITED NATIONS PROGRAMME ON HIV/AIDS. 2014. The gap report. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

KGANYAGO, L.N. 2006. Description of risk factors in foster care failure. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

LOUW, L. & JOUBERT, J.M.C. 2007. The experiences of adolescents orphaned by HIV/AIDS-related conditions. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 43(4):376-391. [ Links ]

MKHIZE, Z.M. 2006. Social functioning of a child-headed household and the role of social work. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

ORME, J.G., COX, M.E., RHODES, K.W., COAKLEY, T.M., CUDDEBACK, G.S. & BUEHLER, C. 2004. Casey home assessment protocol (CHAP): technical manual. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee, Children's Mental Health Services Research Center. [ Links ]

ORME, J.G., CUDDEBACK, G.S., BUEHLER, C., COX, M.E. & LE PROHN, N. 2003. Casey foster applicant inventory (CFAI): technical manual. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee, Children's Mental Health Services Research Center. [ Links ]

POULIN, J. 2005. Strengths-based generalist practice: a collaborative approach (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/ Cole. [ Links ]

QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF CHILD SAFETY. 2005. Practice paper: Assessment of foster carer applicants. Queensland, Australia: Queensland Government. [ Links ]

SALEEBEY, D. 2002. The strengths perspective in social work practice (3rd ed). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

SINCLAIR, I. & WILSON, K. 2003. Matches and mismatches: the contribution of carers and children to the success of foster placements. British Journal of Social Work, 33:871-884. [ Links ]

SOANES, C. & BRANFORD, W. 2002. South African pocket Oxford dictionary (3rd ed). Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN SOCIAL SECURITY AGENCY. 2014. Fact sheet: Issue No 5 of 2014 - 31 May 2014: A statistical summary of social grants in South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Social Security Agency. [ Links ]

STOCKBURGER, D.W. 1996. Introductory statistics: Concepts, models and applications. [Online] Available: http://www.psychstat.missouristate.edu/introbook/sbk04m.htm. [ Links ]

The Children's Act, Act No. 38 of 2005. 2005. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ] The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act No. 108 of 1996. 1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

THIELE, S. 2005. Exploring the feasibility of foster care as a primary permanency option for orphans. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Masters dissertation) [ Links ]

THOMAS, E.J. 1984. Designing interventions for the helping professions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

THOMAS, E.J. 1992. The Design and Development Model of practice research. In: GRASSO, A.J. & EPSTEIN I. Research utilization in the social services: innovations for practice and administration. New York: Haworth Press. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 1989. United Nations convention on the rights of the child. [Online] Available: http://www.unicef.org/crc/index_30160.html. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 2009. Guidelines for the alternative care of children. Innsbruck: SOS Children's Villages International. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. 2014. The Gap Report. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

VAN DER RIET, K.E. 2009. Foster care: the experiences of birth children. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (MA dissertation) [ Links ]