Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 n.2 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-2-499

ARTICLES

The lived experiences of Black African mothers following the birth of a child with down syndrome: Implications for indigenisation of social work

Mathebane Mbazima

Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. <Mathems1@unisa.ac.za>

ABSTRACT

The article discusses the lived experiences of black African mothers following the birth of a child with Down syndrome and implications of this for the indigenisation of social work practice in South Africa. A retrospective qualitative study following a phenomenological design was undertaken. Findings indicated that giving birth to a child with Down syndrome evokes intense psychological and social reactions from the mother, family and community. The cultural norms and values of black African people, including principles of ubuntu and their belief in collectivism, provide important opportunities, support systems and resources that could be pooled for efficient and effective helping intervention.

INTRODUCTION

"I am where I am" is a common dictum and well-known point of reference for Afrocentric scholars (Asante, 2000; Asante, 2003; Kuse, 1997:21; Mazama, 2003; Schiele, 2000; Thabede, 2008:239; Tshabalala, 1991:74) and by extension African proponents of indigenisation in social work (Gray, 2005; Midgley, 2008:31; Osei-Hwedie, 2002:312; Osei-Hwedie & Rankopo, 2008). The dictum presents many opportunities and challenges for contemporary social work, as did the debilitating social problems arising from industrialisation and urbanisation that gave birth to social work as a profession and academic discipline dictated by a desire to maintain social order (Lorenz, 2008; Payne, 2005). As a human service profession, social work in its current Eurocentric form cannot afford to remain aloof from the pertinent and pressing question of its appropriateness and relevance in responding to local social problems confronting black Africans (Brydon, 2011:156; Gray, 2005; Sewpaul, 2005). Despite numerous attempts by African scholars (Gray, 2005; Midgley, 2008:31; Osei-Hwedie, 2002:312; Osei-Hwedie & Rankopo, 2008; Thabede, 2008:239) to adapt social work practice to the African context, its Eurocentric nature allows little space for the African voice, because of the paradoxical nature of the relationship between the Eurocentric and African worldview (Kuse, 1997:19; Thabede, 2008:234).

The birth of a child with Down syndrome (DS) in a family is a traumatic experience with adverse psychosocial effects. For the historically disadvantaged black African community as compared to their previously advantaged white counterparts, the experience of giving birth to a child with abnormalities is even more difficult, given the harsh historical, social and economic predicaments that characterise black African communities (Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012). There is no literature available on social work services rendered to black African mothers and families following the birth of a child with DS in South Africa. Consequently, there are no specific protocols or guidelines developed for social work services in this regard -hence, the exploratory nature of the study that forms the basis for this article. Generally, the extent to which the intervention of a social worker will be effective in any given situation will depend on the degree of congruence between the social worker's approach and the client's frame of reference as defined by their socio-cultural context (Osei-Hwedie, 2002:312). The lack of fit between the social worker's approach and the client's frame of reference may undermine the effectiveness of the helping process and breed role confusion (Kuse, 1997:19; Thabede, 2008:234). As Thabede (2008:234) argues, "the adoption of the value base of social work in its pure form from the European and American societal value system breeds role confusion" for social workers in the African context. For instance, Thabede (2008:20) highlights the fact that the belief of social workers in the worth of the individual, the right of the individual to determine his/her own destiny, and the recognition of the individual's potential to govern the self militates against the emphasis of the African worldview on collective good and ubuntu. Thabede (2008:235) postulates that individual concerns are subordinate to group interests in the African cultural context. It is important to underscore that, although the African worldview places the emphasis on the collective consciousness, this does not negate the existence and indeed the significance of individuals making up the collective, but rather emphasises that individual identity is construed as a collective identity. This means that individual uniqueness is acknowledged and celebrated as an element or part of a collective system.

The study on which this article is based sought to uncover the psychosocial needs and coping strategies of black African mothers. The article highlights the implications of the needs and coping strategies of black African mothers for the indigenisation of social work in South Africa. It draws on research conducted with black African mothers following the birth of a child with Down syndrome in the South African provinces of Gauteng, North West, Limpopo and Mpumalanga.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The DS condition was first described in 1866 by Langdon Down (Mueller & Young, 2005:53). According to Mueller and Young (2005), DS is the most common chromosome abnormality found in children. There are several other known chromosomal abnormalities in addition to DS and together they account for about 50% of all spontaneous miscarriages and 0.5-1% of live-born babies (Mueller & Young, 2005:54). The DS condition is characterised by mental retardation, heart defects, distinct facial features and an increased susceptibility to leukaemia and the early onset of Alzheimer's disease (Harper, 2004:30), affecting 1 in 650 to 700 individuals world-wide (Mueller & Young 2001:54).

Based on the literature reviewed on the burden of congenital disorders worldwide, the article argues that the effect of these disorders has been greatly underestimated. As argued by Christianson and Modell (2004:220), it has not been recognised, especially in middle- and low-income nations such as South Africa, that there is a great need for, and indeed that possibilities exist for, care and the prevention of congenital disorders. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the prognosis improves as care improves and that an increasing proportion of infants with congenital disabilities survive as services become available (Christianson & Modell, 2004:220). Furthermore, as the number of infants who survive increases, the number requiring care increases incrementally (Christianson & Modell, 2004:220). The treatment of and care for children with congenital disorders includes diagnosis, therapeutic intervention and genetic counselling with psychosocial support (Christianson, Howson & Modell, 2006; Christianson & Modell, 2004:223).

The Department of Health (2001) developed a set of policy guidelines that called for an integrated and holistic approach in patient care. The services packaged in the guidelines include the integration of social work into the care and treatment team to assist patients deal with the psychosocial aspects of their medical condition. This presents opportunities and challenges for social workers. The opportunity presented is for social workers to practise within a multidisciplinary medical setting and the challenge is for social workers in health care to acquire the appropriate knowledge and skills in various medical specialties that they work in, such as genetics in primary health care. Having acquired such knowledge and skills, social workers in health care will be able to develop relevant intervention protocols or models that can help curb the heavy psychosocial and financial cost of raising a child with DS.

The birth of a child with DS is a shocking and traumatic experience for mothers. Parents react with dismay on hearing that their new-born child has an abnormality (Cowles, 2003:13). It is the author's observation that the birth of a child with DS does not only create financial, social and medical burdens for the individual or family, but it also places fiscal strain on the state, as the child will need social assistance in the form of a disability grant, a special school, regular medical attention and, in some cases, major surgery, as well as institutionalisation where there is serious disability (Christianson & Modell, 2004:220). The Department of Health (2001:53) estimated that, on average, the cost of caring for a child with DS could amount to about R15 000 to R20 000 per annum for basic medical care. An additional cost of R50 000 can be incurred for a heart surgical procedure, where this is necessary. These figures must have doubled over the years through inflationary pressures, but current estimates are not available.

Given the above background, it is clear that the parents of a child with DS will need ongoing professional support. The author observed that the DS condition has not always been known or understood amongst African families. This only changed recently when pre- and post-natal diagnostic technology was introduced to few major hospitals in South Africa (Department of Health, 2001). The black African mother of a child with DS relied on her traditional belief system to interpret and manage the condition without any professional support. One acknowledges that a lot has changed to date, including improved access to early diagnostic technology as well as counselling and support. Amongst observations made in health care practice over the years is that most African families with DS who are fortunate enough to get a confirmed diagnosis of the condition get referred for psychosocial support at the health-care institution. The initial counselling is done by a genetic counsellor (most of whom are not social workers), who in turn refers the client to a health-care social worker and a support group for on-going support (Department of Health, 2001). The health-care social worker will in turn refer the client to welfare services or the Department of Social Development for processing of social security aid in the form of a disability grant and other relevant welfare services (Department of Health, 2001).

The relationship between social work and context

Having discussed the DS condition, we will now focus on social work before we proceed to look at issues of indigenisation. Interestingly, Brydon (2011) advances an argument that the origin of social work in the global North and West can be traced back to indigenous ways of responding to human needs. According to Brydon (2011:156), social work emerged in the Western context as a consequence of the secularisation of the welfare role of religion as well as being a response to the social problems that arose in response to industrialisation and urbanisation. Brydon (2011) further argues that the inception of social work was also a response to concerns about the social unrest that arose from urbanisation and industrialisation, with the objective of maintaining social order. This means that Western social work is indigenous to the Western context, despite masquerading as universal. Similar sentiments are shared by the founding father of Afrocentricity, Asante (2003) when he cemented the seminal African (Afrocentricity) paradigm and argued that Eurocentrism is essentially an ethno-cultural paradigm that was parachuted into other countries as part of the broader colonial project. Midgley (2008) confirms this assertion and contends that the application of Eurocentric models to diverse contexts and cultures has resulted in alienation of people and a consequent inability to respond to real issues affecting people in non-Western countries. Indeed, as the proponents of indigenisation claim, social work is shaped by the context within which it originates.

Indigenisation of social work practice

Indigenisation refers to a process towards achieving relevance of theories and practice, as well as of the values, norms and philosophies that form the basis for practice (Osei-Hwedie, 2002:312). Midgley (2008:31) defines indigenous social work as "appropriateness, which means professional social work roles must be appropriate to the needs of different countries and social work practice". Additionally, indigenous practice should follow societal procedures, norms, ideas and practices. Indigenisation, thus, also translates into practice within a specific socio-cultural context (Osei-Hwedie, 2002:312). Osei-Hwedie (2002:312) further argues that in Africa the dependence of social work on Western worldviews disguised as universal values makes it ineffective in the face of the prevailing social problems and needs imposed by contextual conditions. Nothing could be found in the literature on indigenous social work practice with black African mothers of children with DS.

The psychosocial effects on black African mothers of giving birth to a child with DS

Congenital abnormalities, including mental retardation, as found in children with DS are perceived largely as either a curse or the result of witchcraft in most black ethnic cultures (Cowles, 2003:13). This understanding is not supported by social work interventions underpinned by a Western cultural orientation, and this leads to a discrepancy between the actual felt needs and the helping process offered. For instance, there is no place for traditional healing methods, spirituality and witchcraft in the current Western-oriented social work education and practice, resulting in little or no knowledge of such phenomena. The black African mothers raising children with DS have to navigate between and juggle the two worlds of the African paradigm and the world of professional assistance deeply embedded in a Western worldview. Thabede (2008:235) argues that it is inappropriate to apply Eurocentric theories of human behaviour to explain the behaviour of Africans as the two are underpinned by different worldviews.

Social work as a profession has four fundamental values, viz. respect for the worth and inherent dignity of humans, empowerment, self-determination and confidentiality (Cummins, Sevel & Pedrick, 2006; Grobler, Schenck & Mbedzi, 2014:39). According to Grobler et al. (2014:41), the overarching value undergirding social work helping process is that of individualisation, implying that the social worker "assumes the internal frame of reference of the client, to perceive the world as the client sees it ... to lay aside all perceptions from the external frame of reference while doing so". This is consistent with the Western worldview, as it negates the fact that the individual frame of reference is a product of socialisation and cannot be viewed in isolation. The Western worldview is characterised by an individualistic value orientation to social functioning, contrary to the African worldview which, whilst acknowledging individual responsibility, puts much emphasis on the collective or group cohesiveness (Thabede, 2008).

The clan name system is but one example of a distinct African cultural experience or practice signifying a form of group support and cohesiveness absent in the Western worldview. Whenever there is a festivity, a ceremony or a crisis in most African families, families belonging to the same clan pool their resources together both in cash and in kind (Tshabalala, 1991:73). Consequently, Tshabalala (1991:74) states that "the African paradigm is underpinned by a distinct value system from the Western one". The basic values on which the African paradigm is premised include, amongst other things, the following: importance of the family, importance of the group, respect for life and elders, fear of God, and a deep commitment to sustaining meaningful community life through shared produce, shared problems and sorrows as enshrined in the principle of ubuntu/botho/xintu (Tshabalala, 1991:74). Ubuntu refers to humaneness, "a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness, that individuals and groups display for one another" (Mangaliso, 2001:24). From the above illustrations of the concept of ubuntu, it appears that group consciousness and cohesiveness are central characteristics of African society.

The article contends that most African ethno-cultural practices are based on values and philosophies that conflict with Western values (Kuse, 1997:21). Such values are inherent in the traditional patriarchal family system, the philosophy of keeping family matters within the family (secrecy), and the traditional beliefs in ancestral powers and witchcraft (Thabede, 2008:239; Tshabalala, 1991:74). The African belief in sympathy militates against empathy in counselling (Tshabalala, 1991:74). Additionally, the idea of sitting up straight, having an open posture, and leaning forward and maintaining eye contact in the social work helping process are some of the common practices in counselling associated with the Western worldview, but alien to the African worldview.

The article further highlights that there is a general lack of literature on social work services to African mothers of children with DS and their families, despite DS being a debilitating condition with immense negative psychosocial effects. The lack of literature in this area is in itself a problematic gap that must be closed. The DS condition is common worldwide but, in South Africa studies of black neonates with DS have shown that 55% of infants with DS were born to mothers of advanced maternal age, i.e. over 35 years (Christianson et al., 2006:10).

There is a stigma attached to giving birth to a child with congenital malformation or mental retardation as found in DS among African families (Boswell & Wingrove, 1974, Christianson, Zwane, Manga, Rosen, Venter, Downs & Kromberg, 2002:180; Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012; Rosenkranz, 2004). In African families such a birth is widely viewed as a curse by the ancestors for some form of misdeed either by the parents or by the family as a whole (Christianson et al., 2002). Anecdotal incidents have been reported of gross neglect and abuse of children with DS or any other condition involving intellectual disabilities (Rosenkranz, 2004). These include incidents of children being chained and locked up in houses for years by parents or families who did not want community members to see any child with a disability (Rosenkranz, 2004).

There are serious challenges resulting from a lack of resources and the inherent socioeconomic inequalities that continue to prevail in black African communities (Pillay, 2001). The majority of black Africans, particularly those residing in deep rural areas, are still trapped in extreme poverty with little or no access to basic resources and infrastructure (Pillay, 2001). The above challenges further complicate and frustrate parental efforts to provide care and support for the child with DS (Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012). In addition to the overwhelming psychological reactions associated with discovering that the child has DS, raising such a child within a black African family is extremely difficult given the reality of widespread poverty and economic deprivation (Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012). Thus, the socio-cultural and economic landscape of black African families raising children with DS presents challenges and opportunities that call for empirical research to identify, harness, use and build up a responsive service-delivery system.

GOAL OF THE STUDY

The aim of the study was to develop a better understanding of the psychosocial needs and coping strategies of black African mothers following the birth of a child with DS.

METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN

A qualitative research approach was used in a phenomenological, exploratory, descriptive design. Grove, Burns and Gray (2013:705) explain the qualitative research approach as a systematic, interactive and subjective approach used to describe life experiences and giving them meaning. In this case, the lived experiences and realities of black African mothers of children with DS were explored and interpreted. The study on which this article is based is phenomenological as it sought to unearth the lived experiences of black African mothers following the birth of a child with DS.

Eleven participants were included in the study that formed the basis of this paper. Seven participants formed a focus group and another four were included in individual interviews. This allowed the researcher an opportunity to counteract the limitations of the focus group interview. The selected participants had to be black African mothers with a child more than one and a half years old affected with DS. They should have received some social work service and be currently participating in a DS support group. The purposive sampling method was used as the researcher identified particular criteria for the selection of participants. The participants were recruited from existing DS support groups affiliated to the Down Syndrome Association, Tshwane. The researcher designed two separate data-collection tools, namely a semi-structured interview guide and a set of focus group prompts.

According to Neuman (1997), data analysis in qualitative research involves searching the data for patterns and recurrent behaviours. In analysing collected qualitative data, the researcher followed various steps in applying the methods for qualitative data analysis adapted from Neuman (1997). The first step was familiarisation and immersion, which involved reading through, making notes, drawing diagrams and brainstorming to get an overall picture of the findings. The second step was inducing themes, involving inferring general rules or classes from specific instances in a bottom-up approach (Neuman, 1997). The material was perused and the organising principles underlying the material were identified. This is contrary to a top-down approach, where one uses ready-made categories and simply looks for instances fitting such categories. The third step was coding (Neuman, 1997). This involved marking different sections of data as being instances of, or relevant to, one or more of the researcher's themes. The researcher used coloured marker pens to highlight pieces of text. The fourth step was elaboration (Neuman, 1997). Elaboration involved putting information in a linear sequence. The fifth and final step used in analysing qualitative data was interpretation and checking, which involved going back to all steps to make sense of the data (Neuman, 1997). It also involved checking for misplacement of certain texts (Neuman, 1997).

The nature of this study compelled participants to relive their emotionally charged experiences, and this might have evoked emotional reactions of varying significance. The researcher, as a qualified social worker, undertook to exercise considerable caution and be observant in order to detect such reactions and take appropriate steps, which were to include, among other things, referral to relevant support services where necessary. Arrangements were made with the Support Group Coordinator as well as the Down Syndrome Association to provide relevant assistance, if the need arose. None of the participants involved in the study seemed to experience any of the above-mentioned emotional reactions during the interview and therefore none were referred for counselling. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants received relevant information about what the study entailed, based on which they decided to participate in the study. Non-participation in the study did not in any way disadvantage the potential participants. Similarly, participation was not rewarded in any form. Participants reserved the right to withdraw from the study at any stage of the research process at their own discretion.

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

Demographics

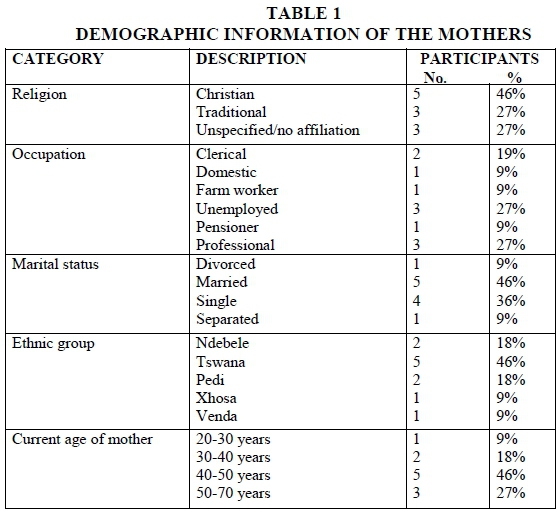

Eleven participants were included in this study. Seven participants formed a focus group and another four were included in individual interviews.

The mothers came from different religious denominations, the majority being Christian (46%) and the remainder being of African traditional belief or unspecified. The age of the mothers ranged from 20-70 years, with the majority (73%) being in the 40-70 years categories. According to Mueller and Young (2005), women above the age of 35 years are considered to be of advanced maternal age (AMA). The maternal risk of giving birth to a child with DS increases with maternal age (Mueller & Young, 2005). In the black African context, this situation is exacerbated by the fact that older women tend to have children rather than younger women (Christianson, 1996). This is contrary to the Western context, where more younger women tend to have children than older women, resulting in a higher total of DS births to younger women (70-80%) and only 20-30% of children with DS born to mothers above the age of 35 (Christianson, 1996). A small percentage of 19% of the participants had formal education and were doing a professional job requiring some skill, whereas the majority (27%) were unemployed, with the remainder employed as either domestic workers or farm workers, or were pensioners (9%). The economic conditions of the participants have implications for their ability to provide for their needy children with DS. Those in stable and well-paying jobs may be better able to provide financially than those who are unemployed or earning low salaries, as is the case with farm and domestic workers. The mothers of AMA are more likely to be inclined to adopt traditional and cultural beliefs and practices than their younger counterparts, who tend to follow a modern lifestyle. Furthermore, the age of the mother becomes an important variable as it influences the way they navigate challenges associated with raising a child with DS.

Theme 1: Manner of disclosure of bad news

Firstly, most participants felt that they needed to understand DS as a condition better. They needed information about the condition to be given to them and their families. Almost all the participants highlighted that they were not happy with the way in which the disclosure of bad news about their child's condition had occurred. According to the participants, no proper counselling was provided, but mothers were told that they had given birth to a child with some medical problem. Participants pointed out that, because of the shock that came with the disclosure of bad news, anything else that was said afterwards was not properly internalised. As a result, they remained ill-informed about the condition even after various medical and allied professionals had spoken to them.

They knew that their child had a problem, but could not understand clearly what the problem was and therefore they were not in a position to explain it to their families. Most of them were alone when told by the doctor or nurse that their child had DS. All participants expressed how they had wished in vain for their family members to have been given accurate information in order to accept the situation and provide mutual support to each other as a family unit. It was a generally held perception among the participants that giving information to mothers alone instead of to the mother and father and/or another family member places a huge burden on the mother to have to give the news to the other members of the family.

"The in-laws need to understand the situation better, but are never involved in the process, " said one of the participants.

The participants reported that, if other family members are not involved, the mother automatically becomes the middle person to relay information to the family and she is often met with stigmatising attitudes and blame. As argued by Cowles (2003:13), the disclosure of bad news about the diagnosis of an abnormality in a child is a shocking and traumatic experience for parents. Cowles (2003) further emphasises the fact that a diagnosis of DS made prenatally or shortly after birth makes it a sensitive issue to handle. The fact that there is a stigma attached to giving birth to a child with congenital malformation and mental retardation as found in DS among African families (Boswell & Wingrove, 1974; Christianson et al., 2002:180; Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012; Rosenkranz, 2004) is a further reason for the disclosure of the diagnosis of DS to be handled with care. As a result, the Department of Health (2001) created a platform through its policy guidelines for interdisciplinary collaboration and cooperation undergirded by a desire to achieve a holistic approach in total patient care. Unfortunately, the experiences of the mothers in this study prove otherwise. Most of them were not provided with counselling and where counselling was given, it was abrupt and given to the mother alone. Language limitations might have been an issue as most of them reported that, although they understood that something was wrong with their child, they were not in a position to explain it to another person. This may also be influenced by the fact that there is no vernacular translation of the word DS in the African context. Furthermore, most of the words used to explain causes and mechanisms of DS (e.g. chromosomes) cannot be translated into the vernacular.

Theme 2: Practical needs and resources

Participants felt that, in addition to the need for information about the condition, they also needed general information on the rights and entitlements of the child with DS. Parents needed to know what the rights of the children are with regard to the various services they need.

"How do we move the child to school? "

''How do we prepare the child for work and how do we get the child to work? "

"Where to get developmental stimulation and therapy for the child? "

' How to go about getting a disability grant or care dependency grant, if necessary? "

"Where to get psychological support as mothers and guidelines on how to look after their children? "

One of the participants mentioned that a schoolteacher told her that her child would only qualify for a grant after he had reached the age of 18 years.

"The need arises immediately after birth and has to be met for the better growth and development of the child. "

" How does one begin to satisfy such needs without the provision of necessary social security support? "

Christianson et al. (2002:180) documented that children with DS endure a lifelong chronic disability with excessive needs. These needs include early developmental enrichment programmes, including physiotherapy and speech therapy; special education; medical treatment for recurrent respiratory infections and other medical complications (Christianson et al., 2002). These needs add to an already difficult socio-economic state of extreme poverty with little or no access to basic health services, social facilities and infrastructure (Pillay, 2001). The majority of participants in the study, particularly those residing in deep rural areas came from poor families. The findings confirm that socioeconomic challenges do complicate and frustrate parental efforts in trying to provide care and support for the child born with DS. Most mothers expressed a need to provide the best possible care and love for their child with DS, but were frustrated by the lack of resources and facilities to support their efforts. The positive sentiments expressed about the child with DS, including the realisation that these children have unique qualities, is consistent with the final stage of acceptance in Kubler-Ross's (1969) grieving process.

Theme 3: Participants' emotional reactions and ascribed meaning

All mothers confirmed that the experience was very stressful for them, particularly the first few months after learning that their child had DS. They reported that it was not easy for them to come to terms with the experience, but it got better as time went by. Some mothers reported that it was so painful that they felt like crying but could not cry, as it is a taboo in their culture to cry for a person while the person is alive. Crying for a person is only permissible when mourning the death. There is also a belief among black Africans that crying for a living person may lead to the person dying prematurely.

As pointed out by various scholars, when people are faced with tragic news or events, specific needs arise and they adopt various coping mechanisms, but go through a similar process (Hsia, Morris & Bailey, 1997). The initial reaction of parents and family members to the diagnosis of DS was shock (Hsia et al., 1997). Kubler-Ross (1969) developed a five-stage model for understanding the grieving process of death and dying. The researcher is of the view that similar principles can be used to understand the way in which people cope with different traumatic events and losses in their lives, including how families cope with the birth of a child with a handicapping condition such as DS. When asked about how they coped, some explained that they relied on their belief in God and pastoral counselling as a coping strategy, while others tended to consult traditional healers, prophets, close family members and friends for support. None of the mothers mentioned formal support systems as a resource that they considered useful in helping them cope with their situation.

There was general consensus on the need to be secretive about the condition of the baby. Some reported that they became secretive as a way of managing stigma, while others needed to first learn to come to terms with the experience before exposing it to others. This is consistent with what Kubler-Ross (1969) asserted as part of the bargaining stage in the grieving process. Kuse (1997:21) highlighted some of the inherent values and philosophies of black Africans as including "the philosophy of keeping family matters within the family and not to open up for strangers and traditional beliefs in ancestral powers and witchcraft". However, they all confirmed that at the time of the research they were open about their children's condition. They all expressed a passionate need to go out and educate other people about the condition. The positive sentiments expressed above show that the mothers have accepted the condition, which is consistent with the final stage of acceptance in Kubler-Ross's (1969) grieving process.

The mothers demonstrated courage and determination to face the challenges associated with having a child with DS. They all acknowledged that it is not easy, but that it is worthwhile persisting. They generally perceived giving birth to a child with DS as a "gift from God". One of the respondents stated the following:

"Joo . go tsere nako go amogela, Gago easy. Mara ngwana wa gago ke wa gago, ke mpho ya modimo." (It took time to come to terms with the experience, it's not easy, but one eventually accepts as it is a gift from God.)

Most mothers asserted that their love for the child and their acceptance of the child as a gift from God kept them going. It appears from the findings that deep religious convictions influenced parental adjustment to the child with DS, particularly with regard to how parents interpret and understand the presence of such a child in the family. Other participants reported that they had consoled themselves by comparing their child with other children they met who do not receive adequate stimulation such as theirs does and consequently tended to be far more backward in their developmental milestones. In view this, they considered themselves lucky.

It is interesting to note that most participants in the study continued normally with reproductive activities. No significant gaps in childbearing were noted in subjects that could be linked to the birth of a child with DS. The uninterrupted sequence in reproductive activities amongst mothers may be an indication of their having accepted the situation and moving on normally, or it may also have been influenced by the high regard for life in the black African community. This is contrary to findings of studies conducted in other countries. Tips, Smith, Perkins, Bergman and Meyer (1963) found that the birth of a child with DS to 24 Oregon, USA families was so traumatic that reproduction ceased in these families. Similarly, Ando and Tsunda (1978) found that the reproductive activity of Japanese mothers of children with DS had declined significantly after the birth of a child with DS when compared with mothers of normal children matched on the basis of age.

Theme 4: Formal support systems or social work intervention

The general perception of participants regarding social work intervention is that it partly addressed some of their needs, while leaving significant other needs unattended. Firstly, participants reported that the social work intervention received was focused mainly on addressing practical needs such as assistance with accessing social grants. Thus none of them received adequate psychosocial support. Consequently, their needs had not been addressed at that level through professional intervention. However, they resorted to other avenues such as the self, family and friends to help cope with the situation. According to Cummins, Sevel and Pedrick (2006:4), the helping process in social work begins with engagement and assessment. It is during this stage that the social worker engages the client on the presenting problem in order to find underlying issues that give rise to the presenting problems. Cummins et al. (2006:4) further emphasise that assessment is an on-going process in social work. Thus, the finding that the participants' needs were not fully addressed points to an omission on the part of the social workers. The omission may be attributed to a number of factors including the fact that social workers may have failed to start at the point where the client was and consequently missed out on important information. The social workers may also have failed to see things the same way the client sees them by allowing the client to lead the process; the social workers may have ignored critical contextual issues that shaped client's reality.

Secondly, intervention was not holistic. The individual targeted was either the mother or the child, and the two were targeted depending on the nature of their presenting challenges. For instance, if the mother presented with a lack of proper accommodation for the child, the social worker would work towards addressing this problem. If the child needs institutionalisation in the social worker's view, he or she would work towards getting the child into an appropriate institution. Again, the lack of a holistic view of the client's situation as revealed by the findings seems to have been an omission on the part of the social workers. Cummins et al. (2006) assert that social work intervention plans should take into account social systems that have an impact on social functioning in a holistic and integrated manner. The findings point to a worrying trend in the practice of social work veering away from its frame of reference. Cummins et al. (2006) state that the unique focus on the person in their environment is one aspect that sets social work as a helping profession apart from others. It is through an in-depth assessment and a person-in-environment perspective that social workers are able to connect the person to significant systems and factors in his/her social environment.

The findings on the above two points are consistent with arguments made by the proponents of indigenisation in social work (Gray, 2005; Midgley, 2008; Osei-Hwedie, 2002; Thabede, 2008), namely that social work roles must be relevant and appropriate to the needs of different socio-cultural contexts. The fact that these mothers were able to address some of their concerns through the family system attests to the fact that formal social work services were distant from this reality. The findings point to the fact that the intervention was not integrated and lacked a holistic focus. This can be attributed to the individualistic orientation of social work influenced by Western values. As argued by Thabede (2008:235), individual concerns are subordinate to group interests in the African context and most activities are based on group effort. The experiences of the mothers in this study show that the management of the experience of giving birth to a child with DS was a family affair from the beginning, although the formal support system did not engage the family as a unit from the beginning. This resulted in a disjuncture that the mother had to manage.

Thirdly, treatment and care options came as prescriptions to mothers from social workers. The form of support given was mainly logistical aid such as assistance with applications for a care dependency grant and placement of children with various special institutions. Some participants were advised during the process of applying for a care dependency grant to place their child with DS in an institution. Participants could not understand why they should place their child with DS in an institution. For instance, one participant expressed the following sentiments:

"I asked myself and them, for what good reason must I take my child to Sizanani when I am alive and my child is healthy andfresh? "

There seemed to be a generally negative attitude towards institutionalisation amongst the mothers, echoing an African proverb that says "Tlou ga e imelwe ke mmogo wa yona " (An elephant cannot be burdened by its own body part). This means that it is a divine responsibility of parents and not of institutions to look after their children. As noted by Ryke, Ngiba and Strydom (2003:139), "traditional cultural practices of black African people to keep their elderly persons with them remain a stumbling block to getting them to utilise the provision of institutional care by the government". It was found that black people prefer utilising their extended family systems instead of institutional care on the basis of their belief of "not throwing away" their people (Ryke et al., 2003:139). In other words, children or any family member with special needs related to some form of disability or impairment in functioning cannot be perceived as burdens warranting institutionalisation. This conviction provided positive reinforcement in helping mothers to accept and cope with their child with DS, including pooling of resources across the extended family system to care for the child with DS. Kuse (1997:20) argues that one of the contributory factors to the confusion of the professional role of social work in African communities is "the adoption of the value base of social work in its pure form from the American societal value system".

Lastly, intervention was focused on the individual. It was commonly felt by participants that mothers are left to go through the grieving process unsupported. Most participants expressed their wish for interventions that are family-focused as most of their problems begin in the family and extend beyond the family to the community. They seemed to be understanding and accepting of community-based stigmatisation, but expressed great disappointment at misconceptions and labelling coming from inside the family. Black mothers felt that these family-based misconceptions and negative reactions, if not properly modified and contained, often lead to a complete disintegration of the family system. No attempt was made by social workers to engage the entire family system and the extended family. Van der Walt (1990:37) emphasises that "the spirit of communalism is inherent in traditional African cultures as opposed to the Western cultural emphasis on individualism." Furthermore, traditional African communities view duties towards the community as paramount, hence the belief that "all children in the community are children of all adults in the community - "my child is your child" (Van der Walt, 1990:37). The above provides opportunities for sustaining attempts at change and should be encouraged in the researcher's view.

Theme 5: Family reactions and ascribed meaning by other informal support systems

As argued by Weihs (1998:456), "the stress and strain brought about by the disclosure of bad news about the birth of a child with disabilities is most likely to affect both the biological parents and relationships within the family unit". When asked how their informal support systems or family had reacted to the birth of a child with DS, the responses of participants varied. Most of the participants were satisfied with the support they had received from their close family members (elders, partners and siblings). They felt that close family members were supportive and loving towards their child with DS.

However, some participants reported that they had serious problems with their extended family members gossiping about the cause of the condition. Some extended family members, particularly the in-laws, had attributed the condition to a curse by ancestors, while some attributed it to witchcraft by envious family members. Participants who experienced these sentiments from extended family members described the experience as having a negative influence on their ability to cope with and effectively manage the situation. Furthermore, the researcher noted that, although there is a trend towards individualism amongst black African people as a result of Western influences, the communal life style seem to be more congenial than individualism for black African people.

The literature demonstrated that "relatives, neighbours and friends may tend to pity, ignore or actively avoid the family" (Lea & Forster, 1990:218). The study revealed that almost all participants (100%) were unhappy about the reactions of their neighbours and community at large towards their child with DS. They reported that their child with DS was adversely stigmatised by the community. The community gave them negative labels such as calling the children "Zodwas" (loners). In Atteridgeville, the children with DS are labelled "Zodwas", from the name of the special school they attend, which was named after a community nurse who established the special school (Zodwa). The children were reported to be isolated and not perceived as part of the normal pool of children in the community. The participants felt that they were generally perceived by the community as being "cursed" for deviating in some way from cultural norms. The following responses bear testimony to this:

"Babang bana ba ba badirile di tsheisa. Ke gore o kree motho o mogolo, ge ngwana a feta, ono ra ngwana o are 'Zodwa.' Le bese ya bona e bitswa bese ya dizodwa. Skolo sa bona sespecial akere ke Zodwa." (Some people have turned our kids into laughing stocks; you find an adult person calling a child with DS "Zodwa" (loner), even their school bus is called the "Zodwas bus" (loners' bus).

It appears that the stigma is not only attached to the child, but also to the parents. Boswell and Wingrove (1974) argue that not only are the children with disabilities stigmatised, but the whole family feels looked down upon when other people look at the child with a sense of pity. Participants described the situation as messy and unpredictable. Labelling and stigmatisation, self-pity and mockery resulted from such engagement, particularly with the extended family and other external parties such as friends and neighbours. This is confirmed by the literature review, which showed that stigma remains a challenge for families raising children with mental disabilities (Boswell & Wingrove, 1974; Christianson et al., 2002:180; Department of Social Development, Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities and the United Nations Children's Fund, 2012; Rosenkranz, 2004).

Theme 6: Impact of support groups

The participants expressed their appreciation of an opportunity to belong to a support group and of the efforts of the multidisciplinary team that assist them on an on-going basis, including nurses, physiotherapists, doctors and social workers. They all emphasised that the support group itself assists them to deal effectively with the challenges they encounter in their lives. Paritzky (1986) points out that the self-help group is a valuable and appropriate source of practical and emotional support for families affected by a genetic condition. All mothers interviewed individually asserted that they had found it beneficial to belong to a support group. They found the support group to be particularly helpful in assisting them to explore the best ways of looking after their child with DS. They also acknowledged the fact that support groups go a long way in assisting them to come to terms with the psychosocial trauma created by the birth of a child with DS as it provides a normalising experience. They reported that, through the help of the support group, their relationship with their children improved. Bernardt (1986) emphasises that peer counselling by someone who has faced a similar crisis and has dealt positively with such an experience is also appreciated by families affected by a genetic condition. Bernardt (1986:117) postulates that support groups provide an opportunity for parents to "experience a natural growth towards advocacy and the care given to the handicapped". This not only benefits the child but also those involved in the caring of the child.

DISCUSSION

The discussions with participants in the sample painted a picture of a disparity between the formal and the informal systems that were working towards the same goals. Mothers appeared to be in the middle of this double agenda. The agenda was that of the family system and its traditional ways of problem solving, while the professionals approached this from a technical, rational point of view. This demonstrates the lack of fit between what has been given as an option by the professional helper and the degree of receptiveness by the client. For example, it is normal practice to put children with disabilities into institutions to alleviate the demanding burden of caring for such children by their parents, while in black African traditions such an act is unacceptable and perceived as undesirable and annoying to ancestors. Ryke et al. (2003:139) warn against offering institutionalisation as an alternative care option to black African people on the grounds of the belief amongst black Africans that they should "not throw away" their people into institutions. As stated earlier, most black African ethno-cultural practices are based on values and philosophies that conflict with the Western values that are embraced by the social work helping process (Kuse, 1997).

Participants seemed to rely more on informal ways of addressing needs as they contained an element of self-direction and ownership. The formal interventions are then seen as alien and only necessary to access certain material resources such as grants and acceptance at special schools. In one way or another, the participants had to involve their extended family system in these matters. The participants felt that they have a moral obligation to inform their extended family system about the birth of a child with DS. As pointed out by Van der Walt (1990), elderly persons are traditional birth attendants and traditional health practitioners. This is a very interesting and significant observation, as it directly relates to they way that families with a child with disabilities will manage the condition. The role of elderly persons and the extended family network cannot be ignored.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the article reconfirms earlier research findings by Cowles (2003:13) that giving birth to a child with DS evokes immense psychological and social reactions with grave implications for the mother and her family. The black African mothers participating in this research ascribed certain meanings to the birth of a child with DS such as perceiving it as a gift from God. However, negative connotations were also attached to the birth of a child with DS. Some attributed such a birth to either a curse by ancestors who may be unhappy with the personal conduct of the parents, or to acts of witchcraft. These generally held perceptions had a negative impact on the mothers' ability to accept and come to terms with their experience of giving birth to a child with DS and therefore needed to be modified accordingly to manage the situation.

The cultural norms and values of black people, including principles of ubuntu and their belief in collectivism, provided important opportunities, support systems and resources that could be pooled for efficient and effective helping interventions. Failure to recognise this rendered the social work intervention fruitless. Mothers derive a great deal of strength in coping with challenges associated with the birth of a child with DS from their strong moral basis and the principles of ubuntu. The abundance of interest from the family - both nuclear and extended - as well as other associates such as friends, neighbours and the community at large presented another opportunity in the helping process. Lastly, social work practice seemed to be unpopular amongst black African mothers of children with DS; the participants did not value the professional intervention as a necessary psychosocial healing process, but just as one of the technical formalities that needed to be complied with particularly as a means to access grants and other kinds of assistance for the welfare of the child. The nature of social work intervention added to this perception, as it did not adequately address the psychosocial issues of clients. They perceived social work as attending only to practical needs, as being prescriptive, non-holistic and individualistic. The above situation calls for a re-examination of professional services.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Social work practice has an opportunity to align itself with contextual issues facing black African mothers of children with DS. There is a need to find a fit with values and norms inherent in the black African context, implying an Afrocentric rather than a Eurocentric paradigm in social work practice. When operating within the Afrocentric paradigm, the principles of ubuntu must be embraced and cultural ceremonies, rituals and practices be understood and accommodated, so that clients do not perceive intervention as alien to their indigenous ways, experiences and coping strategies. The two critical elements of professional practice and African paradigm that characterise the African context need to be integrated and work together to achieve a common goal.

It would help to adjust the exclusive focus on the professionally identified needs to include the family system as a whole, taking into account the distinctive black African family structure (extended). The extended family system cannot be ignored as it is part of and influences the nuclear family. Partnerships need to be built between parents, the family (extended where possible) and professionals. When knowledge, skills and resources are shared, black African mothers are enabled through a co-operative arrangement based on the spirit of ubuntu.

The communication systems may need to be improved and gaps within the interdisciplinary intervention process filled. The researcher recommends better co-ordination of professional help, as the family will become involved with a large number of professionals, including paediatricians, general practitioners, geneticists, health visitors and social workers.

Further research on the topic of indigenisation of social work in the black African context is also recommended.

REFERENCES

ANDO, N. & TSUNDA, K. 1978. International incidence of autism, cerebral-palsy and mongolism. Journal of Autism. Child, Schizophrenia, 5(2):267-271. [ Links ]

ASANTE, M.K. 2000. The painful demise of Eurocentrism: an African response to critics. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. [ Links ]

ASANTE, M.K. 2003. Afrocentricity: the theory of social change (revised and expanded). Chicago Illinois: African American Images. [ Links ]

BERNARDT, B. 1986. Self-help/ Peer Counselling. In: WEISS, J.O., KARKALITS, J.E., BISHOP, K.K. & PAUL, N.W. (eds), Genetics support groups: volunteers and professionals as partners. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation. Birth Defects: Original Articles Series, 22(2):136-160. [ Links ]

BOSWELL, D. & WINGROVE, J. (eds) 1974. The handicapped person in the community. London: Tavistock/Open University. [ Links ]

BRYDON, K. 2011. Promoting diversity or confirming hegemony? In search of new insights for social work. International Social Work, 55(2)155-167. [ Links ]

CHRISTIANSON, A.L. & MODELL, B. 2004. Medical genetics in developing countries. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, 1(5):219-265. [ Links ]

CHRISTIANSON, A.L., HOWSON, C.P. & MODELL, B. 2006. The hidden toll of dying and disabled children. New York: March of Dimes Global Report on Birth Defects. Report, 31-2008-05. [ Links ]

CHRISTIANSON, A.L., ZWANE, M.E., MANGA, P., ROSEN, E., VENTER, A., DOWNS, D. & KROMBERG, J.G.R. 2002. Children with intellectual disability in rural South Africa: prevalence and associated disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 1(46):179-186. [ Links ]

COWLES, F.A.L. 2003. Social work in the health field: a care perspective. New York: Haworth Press. [ Links ]

CUMMINS, L., SEVEL, J. & PEDRCK, L. 2006. Social work skills demonstrated: beginning direct practice text-workbook. CD-ROM and Website (2nd ed). USA: Pearson Education, Inc. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. 2001. The Policy Guidelines for the Management and Prevention of Genetic Disorders, Birth Defects and Disabilities. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT, DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN, CHILDREN AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AND THE UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND. 2012. Children with Disabilities in South Africa: A situation Analysis: 2001-2011. Pretoria. Government Printers. [ Links ]

GRAY, M. 1998. Approaches to social work in South Africa: an overview. In: GRAY, M. (eds), Developmental social work in South Africa: theory and practice. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 7-24. [ Links ]

GRAY, M. 2005. Dilemma of international social work: paradoxical processes in indigenisation, universalisation and imperialism. International Social Work, 14(3):231-238. [ Links ]

GRAY, M., COATES, J. & YELLOW-BIRD, M. 2009. Indigenous social work around the world: towards culturally relevant education and practice. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

GROBLER, H., SCHENCK, R. & MBEDZI, P. 2014. Person-centred facilitation: process, theory and practice. South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

GROVE, S.K., BURNS, N. & GRAY, J.R. 2013. The practice of nursing research. Missouri: Elsevier. [ Links ]

HARPER, P.S. 2004. Practical genetic counselling (5th ed). London: Butterworth Heinemann. [ Links ]

HSIA, M., MORRIS, M. & BAILEY, J. 1997. Counselling in genetics. New York: Alan R. Lies, Inc. [ Links ]

KüBLER-ROSS, E. 1969. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

KUSE, T.T. 1997. The need for indigenisation of the education of social workers in South Africa. In: SNYMAN, I. & ERASMUS, M. (eds), Indigenisation in social and community work education. HSRC Co-operative Research Programme: Affordable social provision and the Institute for Indigenous Theory and Practice. Pretoria: HSRC Publishers. [ Links ]

LEA, S. & FORSTER, D. (eds) 1990. Perspective on Mental Handicap in South Africa. Durban: Butterworths Professional Publishers. [ Links ]

LORENZ, W. 2008. Paradigms and politics: understanding methods paradigms in an historical context. British Journal of Social Work, 1(28):625-644. [ Links ]

MANGALISO, M. 2001. Building competitive advantage from Ubuntu: management lessons from South Africa. Academy of Management Executive, 15(3):23-34. [ Links ]

MAZAMA, A. 2003. Creole in Maryse Conde's work: the disordering of the Neo-Colonial order? The Romantic Review, 94(3-4):377+. [ Links ]

MIDGLEY, J. 2008. Promoting reciprocal social work exchanges: professional imperialism revisited. In: GRAY, M., COATES, J. & YELLOW-BIRD, M. (eds), Indigenous social work around the world: towards culturally relevant education and practice. Aldershot: Ashgate, 31-45. [ Links ]

MUELLER, R.F. & YOUNG, I.D. 2001. Emery's elements of Medical Genetics (11th ed). New York: Churchill and Livingstone. [ Links ]

MUELLER, R.F. & YOUNG, I.D. 2005. Emery's elements of medical genetics (12th ed). New York: Churchill and Livingstone. [ Links ]

NEUMAN, W.L. 1997. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches (2nd ed). London: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

OSEI-HWEDIE, K. & RANKOPO, M.J. 2008. Developing culturally relevant social work education and practice in Africa: the case of Botswana. In: GRAY, M., COATES, J. & YELLOW-BIRD, M. (eds), Indigenous social work around the world: towards culturally relevant education and practice. Aldershot: Ashgate, 361-386. [ Links ]

OSEI-HWEDIE, K. 1997. Southern African regional approaches to indigenising social work education and practice: the case of Botswana. In: SNYMAN, I. & ERASMUS, M. (eds), Indigenisation in social and community work education. HSRC Co-operative Research Programme: affordable social rovision and the Institute for Indigenous Theory and Practice. Pretoria: HSRC Publishers. [ Links ]

OSEI-HWEDIE, K. 2002. Indigenous practice - some informed guesses, self-evident and possible. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 38(4):311-323. [ Links ]

PARITZKY, J.F. 1986. Self-help for families in crisis. In: WEISS, J.O., KARKALITS, J.E., BISHOP, K.K. & PAUL, N.W. (eds), Genetics support groups: volunteers and professionals as partners. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation. Birth Defects: Original Article Series, 22(2)96-102. [ Links ]

PAYNE, M. 2005. The origins of social work: continuity and change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

PILLAY, P. 2001. South Africa in the 21st Century: some key socio-economic challenges. South Africa, Jhb: Friedrick Ebert Stiftung. [ Links ]

ROSENKRANZ, R. 2004. The shackles of mental disability. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://ww.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/theshacklesofmentaldisability-1.217194. [Accessed: 23/06/2015].

RYKE, E., NGIBA, T. & STRYDOM, H. 2003. Perspective of elderly Black on institutional care. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 39(2):139-148. [ Links ]

SCHIELE, J.H. 2000. Human services and the Afrocentric paradigm. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press. [ Links ]

SEWPAUL, V. 2005. Global standards: promise and pitfalls for re-inscribing social work in civil society. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14(3):210-217. [ Links ]

THABEDE, D. 2008. The African worldview as the basis of practice in the helping professions. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 44(3):233-245. [ Links ]

TIPS, R.L., SMITH, G.S., PERKINS, A.L., BERGMAN, E. & MEYER, D.L. 1963. Genetic counselling problems associated with trisomy 21 Down's Disorder. American Journal of Mental Defic, 69:334. [ Links ]

TSHABALALA, M. 1991. Kinship networks: an analysis on the use of kinship systems for promotion of mental health among the Nguni. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 22(2):72-79. [ Links ]

VAN DER WALT, B.J. 1990. Being human: a gift and a duty. University of Potchefstroom: Central Publication Department. [ Links ]

WEIHS, K.L.1998. Review of family caregiving in mental illness. Family Systems and Health, 16(4):455-457. [ Links ]