Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.52 n.1 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/52-1-481

ARTICLES

Our brothers' keepers: Siblings abusing chemical substances living with non-using siblings

Mr Peter Schultz; Assim Hashim (Nicky) Alpaslan

Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. Nicky <alpaslan@absamail.co.za>

ABSTRACT

Non-using siblings are adversely affected by the substance abuse and related behaviour of their brothers and sisters. This article allows greater understanding of the plight of non-using siblings obtained from 28 participants interviewed in this qualitative study. Findings reflect the relationships, feelings, challenges and coping strategies of the participants as well as their perceptions of the role of social workers in assisting the chemical substance abuser. Strategies are suggested for social work policy and practice to treat chemical substance abuse holistically.

INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

In many families that struggle with a sibling's chemical substance abuse ,1 a non-using sibling becomes his or her brother's keeper, as the struggle with chemical substances is something that seldom happens in isolation; Avis (2003:10) emphasises that drug abuse does not affect only the person abusing substances. Persons struggling with chemical substance abuse are generally involved in a number of relationships such as with a spouse, children and members of the extended family, friends, colleagues, drug dealers, fellow users and, by default, a variety of service providers. Family members, including siblings, who are closest to the person struggling with chemical substance abuse are severely affected by this abuse (Denning, 2010:166; Jesuraj, 2012:36; Kieber, Weiss, Anton, George, Greenfield, Kosten, O'Brien, Rounsaville, Strain, Ziedonis, Hennesy & Connery, 2007:48).

A family caught up in dependency is perceived as a "damaged family" (Gudzinskiene & Gedminiene, 2010:163) or a "fractured" or "split family" (Jackson, Usher & O'Brien, 2006-7:323) because of the continuing destructive behaviour of the substance-abusing family member. A family member's chemical substance addiction affects the family's functioning profoundly; it cuts to the core of every family member and influences every aspect of the family's life (Jackson et al., 2006-7:321). Substance-abusing families experience challenges in relation to the family's functioning, especially within the spheres of cohesion, communication, support and organisation (Burstein, Stanger & Dumenci, 2012:633). In such families individual family members seem to become restricted in expressing their needs, feelings and wishes. A change in family structure becomes noticeable, characterised by distorted patterns of communication and a lack of understanding among family members. The family as a system becomes involved in a process of physical and emotional detachment, and individual members become socially distant from each other. Role changes and role reversal among the sub-systems within the family system become evident, with all energies and activities geared towards survival (Burstein et al., 2012:633; Gudzinskiene & Gedminiene, 2010:163). The non-substance abusing family members try to do everything in their power to keep the family together, if required, at the cost of one or more family member (Benshoff & Janikowski, 2000:157; Zastrow & Kirst-Ashman, 2013:490).

Research into the impact of substance abuse on the family is well documented, both internationally and in South Africa. Based on a study conducted with family members of chemical substance abusers in the United Kingdom, Barnard (2005:1) concluded, among other things, that chemical substance abuse has an adverse impact on non-using family members. They experience feelings of loss, anger, disappointment and shame, as the drug abuse destroys the family roles and normal functioning. Perkinson (2008:242), states that people "who live in addicted homes live in a whirlwind". He states that these environments go out of control and become unpredictable, with the non-using family members becoming preoccupied with the addict and his or her behaviour. They end up with no time left for themselves and their own needs, whilst acquiring a number of maladaptive skills to cope. Matsimbi (2012:5) and Hitzeroth and Kramer (2010:76) point out that South African families of chemical substance abusers are often left with feelings of helplessness, disappointment, frustration and doubts, all of which contribute to increasing anger and hostility.

As a family member's chemical substance abuse affects the individual members of the family and the family system as a whole, empirically-founded literature was located on the topic of the experience-based perceptions of non-using siblings living with a sibling abusing chemical substances. Only four journal articles were found (Howard et al., 2010; Incerti, Henderson-Wilson & Dunn, 2015; Jackson et al., 2006-7; Webber, 2003). In an Australian study conducted with participants with a sibling who has or had a chemical substance addiction problem, Incerti et al. (2015) note that the experiences of having a sibling abusing chemical substances have been sparingly reported when focusing on the topic of, and link between, family dynamics and substance abuse. In reporting on the impact of siblings' illicit drug use on non-using siblings within a Vietnamese community, Webber (2003) pointed out that whilst the concerns and treatment of the drug user take centre stage, the specific concerns of the parents and sibling living with a sibling abusing illegal drugs take second place. Howard et al. (2010) also found that siblings are often ignored in studies on substance abusers, "whereas persons who abuse substances and parents of substance abusers have been studied at some length". In a qualitative research project undertaken by Jackson et al. (2006-7) in Australia, parents of substance abusers were interviewed with the aim of developing an understanding of their experiences of having a substance-abusing adolescent, and of gaining insights into how the non-using siblings experienced the using sibling's drug abuse.

The research reported on in this article was prompted by the fact that there is a paucity of literature on how the aspect of substance abuse is managed within the context of family life (Jackson et al., 2006-7:322; Marinus, 2015:12; Orford, Templeton, Copello, Velleman, Ibanga, & Binnie, 2009:380). The need to address this lacuna motivated this research, which aims at developing an in-depth understanding on how non-using siblings were affected by their siblings abusing chemical substances by focusing on their experiences, challenges and coping strategies in this regard. The need for such research to explore siblings' experience-based perceptions (Jackson et al., 2006-7:329-330), is confirmed by Feinberg, Solmeyer and McHale (2012:43). They assert that the companionship in childhood and subsequent lifelong sibling bonds "yield a family relationship whose power and importance has frequently been underestimated by developmental and family scholars". Siblings living with a substance-abusing brother or sister grow up under emotionally and socially laden circumstances, and are denied the chance of developing natural and meaningful relationships within the family and community (Jackson et al., 2006-7; Webber, 2003). Understanding their plight and developing insight into their experiences, as well as their challenges and coping strategies, provides vital information to develop or adjust social work practices. As far as can be determined, there are no specific professional services to assist the non-using sibling as a person in his or her own right.

The research that explored the experiences, challenges and coping strategies of siblings living with siblings struggling with chemical substance abuse endeavoured to bring about greater understanding of their plight and insight into their need to develop more constructively into adulthood. This information aids in improving social work practice.

In order to provide direction and guide the study, Agee (2009:435) and Mills and Birks (2014:12) suggest the formulation of an overarching research question. In adopting this suggestion and taking note of the fact that when a researcher aims to investigate individuals' experiences, the overarching research question will be phrased from a "what" or "how" perspective (Mills & Birks, 2014:12). The following question was formulated to guide this research endeavour: What are the experiences, challenges and coping strategies of siblings living with siblings struggling with chemical substance abuse.

The methodology of the research, which follows a qualitative approach, and the findings from the responses of the participants in the study are discussed in the following paragraphs.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was decided upon to conduct this study. The aim of qualitative research is to explore and gain an in-depth understanding into an event, situation or process (Jackson et al., 2006-7), to examine phenomena that have an impact on the lived reality of individuals or groups (Mills & Birks, 2014:8), and to uncover the meaning they assign to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2009:4; Green & Thorogood, 2009:38).

The decision to research the topic under investigation through a qualitative lens was further strengthened by Ritchie and Lewis's (2005:32-33) recommendation that the qualitative approach should be employed when the phenomenon to be studied displays the following features:

- When the phenomenon is ill-defined or not well understood;

- When the phenomenon being studied is deeply rooted within the participants' personal knowledge or understanding of themselves; and

- When the phenomenon being investigated is of a delicate and sensitive nature, and when target populations are vulnerable.

Chemical substance abuse has an adverse impact on family life, including that of the sibling living with a brother or sister who abuses chemical substances. As indicated, the topic investigated seems to be inadequately researched (Howard et al., 2010; Incerti et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2006-7; Orford et al., 2009:380; Webber, 2003). Feeling stigmatised, isolated, humiliated and ashamed by a sibling's chemical substance abuse (Jackson et al., 2006-7:327) renders this a sensitive topic to speak about. Furthermore, the siblings exposed to a brother or sister's substance abuse feel vulnerable as they are not clear how to deal with their sibling's substance abuse and conduct (Aldridge, 2014:113; Campbell-Page & Shaw-Ridley, 2013:489). The topic that was investigated, namely how a sibling copes with living with a person abusing chemical substances, is indeed deeply rooted in the participants' knowledge and understanding of themselves; they are seen as the experts able to speak authentically about this topic.

In adopting the qualitative approach the researchers decided to employ the collective instrumental case study and phenomenological research designs, complemented by an explorative, descriptive and contextual strategy of inquiry.

The collective case study (instrumentally used), as a qualitative strategy of inquiry, presented the researchers with an opportunity for an in-depth exploration and gaining insight into certain aspects which are unique to a specific case (Baskarada, 2014:5; Guest, Namey & Mitchell, 2013:14). Cases were purposively selected to collect the most relevant data - i.e. the experiences, challenges and coping strategies of non-using siblings living with siblings abusing chemical substances. The phenomenological research design allowed the researchers to study the perceptions, feelings and/or life experiences of individuals in relation to an event (Lichtman, 2014:300; Guest et al., 2013:10-11). The explorative strategy of inquiry was incorporated based on the fact that exploratory research intends, among other things, to generate knowledge about an under-researched subject such as non-using siblings (D'Cruz & Jones, 2014:21; Grove, Burns & Gray, 2013:18). A descriptive design was employed to provide a description of the information that became available following the exploration (D'Cruz & Jones, 2014:21). The researcher also included the contextual research design as part of the strategy of inquiry. Terre Blanche, Durrheim and Painter (2006:274) postulate that in the social sciences the meaning of words, actions and experiences can be ascertained only in relation to the context in which they occur.

Purposive sampling was employed as the researchers aimed at selecting information-rich cases (i.e. those that could provide a great deal of information about the issues of central importance to the study) (Krathwohl, 2009:172; Suri, 2011:65). Only participants who met the following criteria were included in the study:

- Male or female participants who did not abuse substances and who lived with a substance-abusing brother or sister;

- Participants older than 18 years of age;

- Participants who were available and willing to participate in the study;

- Participants who were fully aware of what the study entailed, and participated of their own free will.

Seven fourth-year social work students were recruited as field workers and given the responsibility of procuring a sample of four participants2 each, preparing the participants for the process of data collecting and analysis of the data. To select participants for inclusion in the sample, the fieldworkers approached gatekeepers (i.e. social workers in the employ of social service providers who work with families with substance-abuse problems in the area where the field worker was undertaking his or her research). The gatekeepers put them in contact with participants who met the criteria for inclusion stated above. Hennink, Hutter and Bailey (2011:96) describe this method of participant recruitment as using formal networks and services to get in contact with potential individuals who may be recruited for participation in a study.

For the purpose of data collection, semi-structured interviews were used. The interviewer adapted questions as the situation dictated (Guest et al., 2013:114-115; Lichtman, 2014:248). The semi-structured interviews conducted by the fieldworkers were structured according to questions in an interview guide formulated for the purpose of obtaining biographical data about the participants and six questions pertaining to the specific topic under investigation. The topic-related questions focused on the following: how the participants became aware of their sibling's substance abuse, how this made them feel, the challenges they experienced, and how they managed to cope with their substance-abusing sibling. They were also asked how they thought social workers may be of assistance in addressing the family situation caused by the substance-abusing sibling.

After 28 semi-structured interviews were conducted and the audio-recordings of the interviews transcribed, the researcher,3 who analysed the data independently from the fieldworkers, arrived at the conclusion that data saturation was achieved (the point where the data collected started to repeat itself) (Hennink et al., 2011:88).

The data analysis commenced independently between the fieldworkers and the researcher who was responsible for the independent coding. Both the fieldworkers and this researcher employed the eight steps provided by Tesch (cited in Creswell, 2009:186) to analyse the data systematically, and to arrive at the themes that subsequently formed the basis of the emerging story or picture.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the researchers drew on the ideas of Lincoln and Guba in this regard as explained by Lietz and Zayas (2010) and Shenton (2004). The following four criteria and strategies for ensuring and establishing trustworthiness as proposed by Guba and Lincoln (cited in Lietz & Zayas, 2010:191-198; Shenton, 2004:64-72) were used for ensuring the trustworthiness of the study:

- Truth value. The strategy for establishing truth value is credibility. This refers to the extent to which the study's findings and interpretations match the meanings of the research participants (Lietz & Zayas, 2010:191). The particular actions taken to achieve credibility included triangulation, which entails "involving two or more sources to achieve a comprehensive picture or point of reference" (Padgett, 2008:186). In this study triangulation of data sources (i.e. interviewing multiple participants); observer triangulation (i.e. the fieldworkers and the researcher analysed the data independently), and triangulation of investigators (i.e. seven fieldworkers were used to collect the data). The credibility of the study was further underpinned through peer examination (i.e. regular discussion and consultations between the fieldworkers and the researcher with other colleagues in the Department of Social Work), the interviewing techniques used by the fieldworkers, as well as the researchers' supervision of the fieldwork process.

- Applicability refers to the degree in which findings can be applied to other contexts or settings and groups (Lietz & Zayas, 2010:191; Shenton, 2004:169). Transferability was the strategy employed to attain applicability. Lincoln and Guba (cited in Ungar, 2003:95) argue that the researcher has the responsibility to provide a "thick description" to make it possible for an interested person to conclude whether transfer can be contemplated as a possibility. For this reason "dense" descriptions of the research methodology and findings were provided.

- Consistency relates to the extent to which the replication of the study in a similar context or with similar informants will produce the same results (Guba, cited in Krefting, 1991:216). Dependability, by way of an dependability audit, is one of the strategies suggested to ensure consistency. To enable such a dependability audit, a dense description of research methodology was provided. To further increase dependability, the coding and analysis of the data collected were done independently (i.e. the fieldworkers analysed each other's transcriptions independently and the researcher also independently analysed the whole data set) (Krefting, 1991:216-217).

- Neutrality refers to the extent to which the study's findings are free from bias. Lincoln and Guba (cited in Krefting, 1991:217) propose that neutrality in qualitative research should consider the neutrality of the data rather than the neutrality or objectivity of the researcher. Guba (cited in Krefting, 1991:217) suggests confirmability as the strategy to achieve neutrality. In this study triangulation and peer examination, as well as a thick description of the research methodology (a strategy referred to above) and the findings to be presented later in this paper were employed to achieve confirmability (Krefting, 1991:221-222; Lietz & Zayas, 2010:197; Shenton, 2004).

Ethical considerations and clearance

The Departmental Research and Ethics Committee at the University of South Africa granted ethical clearance for this project. Obtaining informed consent, outsider anonymity and confidentiality in terms of the confidential management of information, and debriefing were the ethical considerations honoured during this research endeavour.

Limitations of the study

Two limitations need to be mentioned.

- The study's sample did not include all the population groups depicting the rainbow nation of the country, as no participants from the White and Indian race groups were sampled for inclusion into the study.

- The fact that this research project was approached from a qualitative perspective, which is by nature not interested in the generalisation of research findings to the larger population, must be noted as a limitation.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The research findings are presented in two sections:

- the biographical profile of the participants; and

- a discussion on the themes that emerged from the process of data analysis supported by narratives from the transcribed interviews and complemented by a literature control.

The biographical profile of participants

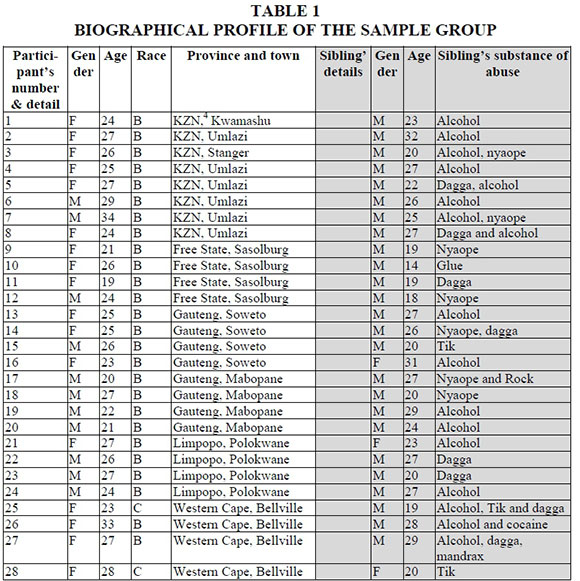

Participants were drawn from five of the nine provinces in South Africa. The reason for only having participants from the five provinces was that these were the provinces where the fieldworkers resided. The biographical profile of the sample is provided in Table 1.

A total of 28 participants (16 female and 12 male), who came mainly from urban areas, took part in this research project. Twenty-six of the participants were black and two were coloured and their ages ranged from 19 to 34 years. All the participants were still living in the same house with the siblings abusing the chemical substances. There were 25 male and three female siblings and their ages ranged from 14 to 34 years.

Table 1 shows that while there were more female participants in this research, 25 out of the 28 siblings abusing chemical substances were male. A similar trend is noticed in the research conducted by, among others, Giordano, Ohlsson, Kendler, Sundquist and Sundquist (2014:1123), Smith and Estefan (2014:418), and Pluddeman (in Florence & Koch, 2011:484). This trend indicates that males are at a higher risk of engaging in chemical substance abuse and addiction. Table 2 shows the siblings' abuse of substances as reported by the participants.

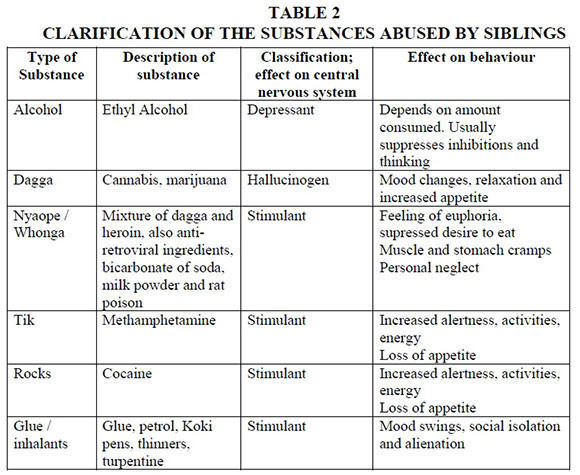

When linking the substances of abuse as presented in Table 2 above with the siblings of the participants (as per Table 1), it seems that alcohol was the drug of choice for most of the siblings. In the case of nine of the siblings, alcohol was the only substance being abused, while for another seven siblings, alcohol was abused together with other chemical substances. This is in line with the worldwide trend noted by Chaulkins, Kasunie and Lee (2014:270) and Hitzeroth and Kramer (2010:43), namely that alcohol remains the substance most often abused.

DISCUSSION OF THEMES

Five themes were derived from the analysis of the answers provided by the participants on the topical questions posed to them. The themes are presented below.

Theme 1: The participants' accounts of how they came to know that their siblings were abusing chemical substances

From the accounts shared by the participants, they indicated that they came to know about their siblings' chemical substance abuse through various avenues.

Most of the participants became aware of their siblings' chemical substance abuse by way of noticeable changes in their siblings' behaviour, pointing to their chemical substance abuse and related activities. This avenue was noted earlier by Jackson et al. (2006-7:324). The following excerpts from participants' responses serve as illustration:

"He became moody, disrespectful and fought with us ..."

"It was so obvious because of the rapid changes that took place in his life. He disappears for weeks and comes back when he wants to ... you can tell by looking at him; he looks dead."

"He was a child who had respect at home. He [then] began coming home late and smelled like cigarettes. Then mom found dagga in his room while she was cleaning. He would ... come home drunk and fight with us."

Bearing out these comments, one of the co-authors in Howard et al. (2010:471) describes how his brother had increasing difficulty in conversing and concentrating and how he had abrupt mood swings in addition to his addictive habits. This underlines the description of families with substance abuse in Kieber et al. (2007:28) as "dysfunctional" families with impaired communication and difficulty in setting limits and maintaining standards of family wellbeing.

Another avenue through which the participants became aware of their siblings' chemical substance abuse was when they accidently stumbled across them using a chemical substance or substances. Webber (2003:234) notes that a sibling's initial discovery of a brother or sister's illicit drug use creates its own stresses, as the sibling may decide not to tell the parents, feels responsible for the brother or sister and tries to help the abusing sibling. The following quotations from the transcriptions taken from some of the interviews underscore this point:

"I saw him with a friend at the bus stop, smoking and drinking alcohol."

"We used to spend a lot of time together until I found him smoking nyaope with a friend in our house ..."

"It took us a long time to realise that he abuses drugs because he lived in a back room in the yard. We then became aware [of his substance abuse] as he is almost always drunk."

"I saw him in the shebeen, drinking. As he was still at school I talked to him ... he then started to use it heavily."

Finding out from others about their siblings' substance abuse was another avenue mentioned by the participants. The following excerpts confirm this:

"My friend phoned me one day and asked me to come to her place to see something. I was busy and could not go so I asked her what was happening. She told me that her brother and my brother were smoking nyaope. "

''Other children came to our house and reported that they saw him [my brother] sniffing glue."

"I was called to the school by his principal and he told me that my younger brother and some others were caught smoking nyaope during break time. He said it was not the first time."

Theme 2: Feelings experienced by the participants in relation to their siblings' chemical substance abuse

All 28 participants indicated that they had been close to their siblings before they found out about their chemical substance abuse. In responding to the question: How did you feel and react when you came to know about your sibling's chemical substance abuse?

The participants did not only refer to their initial feelings and emotional reactions, but also to how they felt and responded later on. These responses are grouped under two sub-themes: initial emotional reactions and feelings, and later emotional reactions and feelings.

Sub-theme 1: Initial emotional reactions and feelings experienced upon finding out about a sibling's chemical substance abuse

Most of the participants' initial reaction was that of shock upon learning about their sibling's chemical substance abuse. Coupled with this were feelings of hurt, anger and disappointment, which were frequently mentioned. Other feelings expressed included feelings of sadness, confusion, helplessness, as well as pity and surprise. This initial shock reaction experienced is not uncommon, for when a family learns about the chemical substance abuse of one of its members, the family is "thrown into shocked disarray" (Barnard, 2005:2). Echoing the feelings experienced by the participants, Howard et al. (2010:469) describe the feelings of a non-using sibling living with a substance-abuse problem, including feelings of "anger, fear, wanting to help, frustration, injustice, love, sadness, hopelessness and helplessness". Similar feelings and emotional reactions were mentioned by the 13 participants (women who have or have had a sibling with a substance-abuse problem) in the research conducted by Incerti et al. (2015:3435). In accentuating this sub-theme, the following comments summarise the combined voice of the participants in testifying to their initial feelings of shock, anger, disbelief and hopelessness upon coming to know about their siblings' chemical substance abuse:

"I was very shocked and I was very angry; I felt like giving him a hiding. I am the only family he has, our parents both passed on and I am providing him with almost everything. I am a petrol attendant because I did not finish school and I started to work to assist my siblings. I felt betrayed by him because I wanted him to be more educated than me."

"At first when I received the phone call, I was very shocked; I could not believe it. After hanging up I told my mother immediately. I did not believe it when I first heard about it."

"It was very hard. I was angry and decided to approach him about it and then lost it; we then had a little fight about it, but I felt guilty about it because if you fight with him he won't fight back."

Sub-theme 2: Feelings and emotional reactions experienced over time by participants in relation to living with a sibling abusing chemical substances

Apart from the initial feelings of shock, disappointment, hurt and anger, and confusion, the participants over time also felt betrayed and experienced feelings of loss of their sibling relationship. Their siblings' chemical substance abuse and resultant behaviour also left them feeling embarrassed. Six of the participants also indicated feelings of concern for their siblings; feelings of guilt and a felt need to support their substance-abusing sibling. One of the participants in the research of Howard et al. (2010:472) spoke about the loss of a brother, because of his alcohol abuse, to whom she was very close, referring to him as different and ugly inside and no longer being her brother. The following quotations taken from some of the transcribed interviews encapsulate the common views of the participants with reference to the feelings and emotional reactions experienced over time by the participants in relation to living with a sibling abusing chemical substances:

"I feel like I am losing him. He spends few time with us but most of the time with his friends sniffing glue. It feels as if his friends are now his close relatives and it is so painful."

"I no longer have a brother."

"I am deeply hurt. I feel like sadness has covered my family, because we first lost our parents and now we lost him."

This feeling of loss of a sibling relationship as indicated in the aforementioned storylines is confirmed by 10 of the participants in the study by Incerti et al. (2015:34) in that they were extremely saddened at the loss of the earlier relationship with their siblings. The other three participants in this study by Incerti et al. mentioned how ashamed they were of their siblings' chemical substance abuse-related behaviour, and that the state of affairs angered them. In fact, they "had given up" on the thought of continuing any relationship with them (Incerti et al., 2015:34). Seven non-using siblings in this study expressed feelings of embarrassment, disappointment and humiliation. The following excerpts encapsulate these feelings:

"I get annoyed sometimes by his behaviour when he is under the influence. People are always talking about his bad behaviour and it makes me feel embarrassed."

"I was embarrassed. Our father is a priest and my mother is a teacher. So when I look at him and I look at us, how are we going to face people and what are we going to say? "

"I am very disappointed and worried about his health. He is only 26 and has his whole future ahead of him. It hurts. It really hurts."

"I was very disappointed, sad and felt humiliated."

Theme 3: Challenges experienced by participants as result of their siblings' chemical substance abuse

The responses elicited from the question on challenges experienced in relation to their siblings' chemical substance abuse centred mainly on the following: challenges related to the sibling's chemical substance abuse-related behaviour (i.e. dealing with theft, lies and the negative attitudes and behaviour of their siblings); challenges related to obtaining treatment for the sibling's chemical addiction; and challenges related to the attitudes of members of the neighbourhood and the community as result of their siblings' substance abuse-related behaviour. These challenges are presented next as sub-themes.

Sub-theme 1: Challenges related to the sibling's chemical substance abuse behaviour (i.e. dealing with theft, lies and the negative attitudes and behaviour of their siblings)

One of the themes that emerged from participants in the study by Jackson et al. (20067:324) was labelled "Betrayal and loss of trust: You had to have the doors locked". The authors found that the participants' relationships with the substance-abusing child in their families were pervaded with deceit, stealing and removing valued possessions from the home, broken promises and dishonesty (Incerti et al., 2015:35). The siblings in Webber's (2003:235-236) study also pointed to a lack of trust between them and the substance-abusing sibling, and that this mistrust results from theft committed by the sibling in order to maintain the drug habit. In confirmation of this sub-theme, and the studies cited, the following quotations capture this challenge commonly experienced by the majority of the participants:

"Missing of items, gadgets like electric jugs, irons, cell phones, clothes and money. Our family lives in fear because the community members are losing their belongings and they always come to our house complaining and threatening to kill him for stealing from them."

"I am afraid to leave him alone in the home as everything gets lost. He has his eyes running all over the place trying to find out what he can steal. We have to hide everything away."

"My mother's things would go missing. She is a pensioner and I am the only one working, so it is very difficult. We all suffer."

"Ever since he started with drugs we get people who come to ask if he lives with us. Some will come and complain about what he did. Police came to tell us that they arrested him for drugs and he has stolen clothes from boys. So all the wrong things he does is reported to us. He will steal things at home and then disappear for days. We do not know where he is and if he is alive or not. Those are the challenges that I come across."

Sub-theme 2: Challenges related to obtaining treatment for the sibling's chemical addiction

Attempts to seek support and treatment for a sibling who is addicted to chemical substances is not unfamiliar. For example, four of the 13 participants in the study by Incerti et al. (2015:36) made attempts to help their sibling receive treatment. Seeking support formed a significant part of their lives. Although no mention is made by these authors regarding challenges experienced in finding support for their siblings' chemical addiction, some of the participants of this study articulated it as a challenge:

"... now he wants to quit but he is addicted. That is the biggest challenge because he spoke to me and said if I had a plan I must help him

"The biggest challenge is to get help for his addiction. He has health problems. We often feel sorry for him."

"We tried to help him; we took him to the hospital when he was going mad and then to a traditional healer where he vomited a goat skin. We also took him to social workers, but this was never followed up because he was aggressive and violent."

"My mother is worried and wants to send my brother to the Transkei. She said it is his friends that make him to do it."

Trying to help and support the family member with a substance-abuse problem as indicated by the above excerpts, while at the same time remaining "connected", is supported by the literature and confirmed by Denning (2010:164). He notes that the supporting family members unintentionally imply the importance of taking care of themselves. Copello, Velleman and Templeton (2005:371) echo this sentiment when observing that these family members need help for themselves and in dealing with their relationship with the substance-abusing family member.

Sub-theme 3: Challenges related to the actions and attitudes of members of the neighbourhood and the community as result of their siblings' substance abuse-related behaviour

The challenges highlighted in this sub-theme are confirmed by the following quotations:

"It is stressful, everyone in the house is stressed, neighbours are always here complaining. We no longer have good relationships with our neighbours. They see our family as a bad one, a cursed one and they blame us for not being able to get help for my brother."

"The challenge I have is that a lot of people in my neighbourhood expect me to go the same route as my brother being an alcoholic . their perceptions of how I am going to be."

"When he uses chemical substances he fights with people and those people come to my home we have to attend to this as they don't get along with us anymore."

Webber (2003:231) claims that Asian American communities are prejudiced towards substance abuse and that "the individual's disgrace is the family's disgrace". This resonates with prevalent attitudes in South African communities.

Theme 4: The participants' ways of coping with the challenges they experience in relation to their siblings' chemical substance abuse

This theme emerged from the question posed to the participants focusing on how they cope with living with a sibling abusing chemical substances.

Coping is defined by Lazarus and Folkman (1984:141) as "constantly changing cognitive and behaviour efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person". Greenglass, Fiksenbaum and Eaton (2006:16) concur when referring to coping as endeavours to deal with stressful events as a multi-dimensional process involving cognitive, behavioural and emotional efforts.

The responses of the 28 participants on how they managed to cope while living with a sibling abusing chemical substances revealed that nine of them were not coping with the situation. The following excerpts speak to this:

"I am not coping. I am not sleeping at night, always thinking about what might happen since my brother is always high at night."

"For now I can't say anyone is coping with the situation because everyone in the home takes him to be a drunkard and know he is good for nothing."

"There is nothing I can do, except to stay away from his matters [actions]. I also make sure that I don't associate with his actions."

Twelve of the participants (and the family as a whole) also used avoidance as a behavioural coping strategy, as the following excerpts illustrate:

"I always lock myself in my room to avoid him. My parents keep quiet when he is in the house; they take a 'don't care' attitude."

"I just leave him because I do not want to be stressed. The family also tried to talk to him but he does not stop."

"As a family we just ignore her. We support our mother who takes this very hard. She prays my sister will change."

'I ignore him most of the time. We take him as insane but pray a lot that he will change."

"I ignore him most of the time because there is nothing I can do; I just ignore him."

In spite of the difficulties created by the chemical substance-abusing sibling, seven of the 28 non-using siblings tried to get help for their brother or sister. The following excerpts point to attempts by the participants and the family to get the substance-abusing sibling to get help:

"I really tried to cope with it . you know I once spoke with him. I cried, I literally cried and begged him to stop because he is my only brother."

"As family we try to find ways to help him. We do not have services in our area, everything is far and public transport is not reliable".

"I went to the social workers but they said they cannot help her if she does not want to come on her own."

On the topic of coping with a sibling's substance abuse, Kirst-Ashman (2013:447-448) as well as Smith and Estefan (2014:419) point to the difficulty in coping with the adverse effects of substance abuse on relationships as a result of dishonesty, deceit and theft by the substance-abusing family member. Ways of coping include adapting to the substance abuse by non-using family members in just leaving matters as they are, trying to keep the family together, and/or taking over responsibilities for the substance-abusing person (Kirst-Ashman, 2013:447-448; Smith & Estefan, 2014:419). Gudzinskiene and Gedminiene (2014:168) explain this behaviour as an attempt by non-using family members (by implication siblings) to protect the family member and the family reputation. Smith and Estefan (2014:425) note that those family members would not disclose the substance abuse, as it is perceived as betraying the substance abusing sibling.

Theme 5: Suggestions on how the participants would like social workers to assist them in addressing their siblings' chemical substance abuse

All 28 participants were requested to reflect on how social workers could assist their siblings who were struggling with substance abuse. Most of the participants suggested that social workers should either talk to substance abusers or take them to a rehabilitation centre, by implication taking responsibility to help abusers get off chemical substances. Some participants indicated that help from social workers must also focus on family members and the family as a whole. The spoke about this along the following lines:

"Maybe the social worker can come and take him to a place that might be safe for him, where there might be no drugs. The problem is that he has access to all the wrong things."

"At first I took him to the social workers, but all they do is talk to him . We want him to go to a rehabilitation centre but they cannot help him if he does not want to go."

"We never talk about it as social workers are very far away. I don't think they have time to listen to the stories of dagga; it is a waste of other people's time because he refuses to change."

"It might be better if the social worker can come and provide therapy for us as a family because of what I have seen it is very stressful for my mother . she is worried as each time she goes to hospital they tell her she has high blood pressure. I think if the social worker should allow him to a rehab centre that is very good as it may help him but I think mostly my mother because she suffers the most."

"They [social workers] can come to our area and do workshops to inform our children on the abuse of chemical substances. Maybe many young children can change their behaviour including my brother and become role models for others."

A dominant discourse deduced from the participants' accounts provided above seems to define the social worker's point of entry to be with the substance abusing person and not so much with the family as a whole.

By way of summarising the discussion on the themes, Table 3 below provided a summary of responses by non-using siblings related to their experiences, challenges and coping strategies in living with a sibling using chemical substances.

CONCLUDING DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In this paper the researchers presented the experiences, challenges and coping strategies of non-using siblings living with siblings abusing chemical substances. When a child in a family abuses chemical substances, the family's functioning rotates around this abusing individual; attempts are made to get the child into treatment and then preventing and managing relapse. However, the individual that is least acknowledged and possibly most highly affected is the non-using sibling (Howard et al., 2010:467; Incerti et al., 2015:35-36).

Most of the participants in this study indicated that they had good relationships with their siblings before the siblings started abusing chemical substances (Incerti et al., 2015:34). When they became aware of their siblings' substance abuse, the participants reacted with shock and disappointment. This revelation triggered a variety of negative feelings and emotional reactions, including sadness, confusion, helplessness, pity, surprise, hurt and anger; over time the participants felt embarrassed, betrayed and experienced feelings of loss of their sibling relationship (Howard et al., 2010:472; Incerti et al., 2015:34). The siblings' chemical abuse inevitably led to a breakdown in the sibling relationship as they distanced themselves emotionally from the substance-abusing siblings (Incerti et al., 2015:34). Usher, Jackson and O'Brian (2007:422) refer to this type of situation as the experience of living with "shattered dreams".

The challenges the participants encountered most were dealing with theft, lies and the negative attitudes and behaviour of their siblings (Incerti et al., 2015:35; Jackson et al., 2006-7:324; Webber, 2003:235-236). Obtaining treatment for the sibling's chemical addiction and having to deal with the negative reactions and perceptions of community members were also raised as challenges.

With regard to the strategies employed to cope with living with a sibling abusing chemical substances, the researchers found that the participants struggled to cope and mostly applied avoidance as behavioural coping strategy (Greenglass et al., 2006:16). They were inclined to ignore the substance-abusing sibling and in some cases even cut their sibling out of their lives. In other cases participants chose to be supportive by trying to find help for their sibling.

The participants' suggestions on how the participants would like social workers to assist them in addressing their siblings' chemical substance abuse implied that they wanted direct interventions from the social workers (i.e. to talk to the chemical substance-abusing sibling; to send the sibling for treatment; to assist the parents and the family; and to conduct educational workshops among the youth about substance addiction). However, it was concluded that none of the participants had specifically expressed the need for social work intervention to empower them to deal with the issue of a non-abusing sibling living with a sibling abusing chemical substances.

Against the backdrop of these conclusions and in view of this topic being so inadequately researched (Howard et al., 2010; Incerti et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2006-7; Webber, 2003), further research on this topic, with specific reference to the following is recommended:

- Focus should be placed on the topic of how a sibling's chemical substance abuse influences the relationships with non-abusing siblings in particular;

- Intervention research is recommended in view of the development of a specific skills training programme aimed at non-using siblings living with a sibling abusing chemical substances to empower them to manage the challenges confronting them Gudzinskiene and Gedminiene (2010:166) claim that the most important challenge for members of the alcoholic's family (by implication also the siblings) is to learn to distance themselves from the substance-abusing sibling and learn to live their own life.

- In view of the gap in the literature on how siblings of a chemical substance-abusing sister or brother deal with or manage their feelings and emotional reactions, future research on this aspect is recommended.

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made in terms of social work practice and policy:

- The development of tailor-made social work interventions in order to treat the effects of an abusing sibling on non-using siblings is suggested (Jackson et al., 2006-7:329-330);

- It is recommended that community education on substance abuse and more specifically the treatment of substance abuse must be intensified at grassroots level in all communities, and not only focus on the "identified patient" (the person abusing chemical substances), but on the family as a whole;

- It is furthermore recommended that both the state welfare organisations and non-governmental organisations make a concerted effort to seriously consider implementing activities to address the problem of substance abuse holistically. This recommendation ties in with the legislation and policies, such as the Prevention of and Treatment for Substance Abuse Act (Act 70 of 2008), which recognises the role of individuals, families and communities and that they need to be involved in prevention and treatment programmes. The Children's Act (Act 38 0f 2005) also refers to children abusing substances and indicates that they must be separated from adults during treatment. The White Paper (1997:70) identifies youths and substance abuse as priority areas in service delivery and emphasises the importance of strengthening family life and the role of effective family functioning in developing children's wellbeing. Gudzinskiene and Gedminiene (2010:168) point out that the main focus of treatment for addiction is on the substance abuser and they contend that family and relatives need equal assistance. Orford et al. (2009:380) concur and argue that services and intervention should be dedicated to family members in their own right.

History has shown that chemical substance abuse has become an integrated part of our lives and will most probably never be eradicated. For this reason we should acknowledge, support and empower non-using siblings to develop and maintain more meaningful lives. We are all our brothers' and sisters' keepers.

Acknowledgement

The researchers would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following fourth-year student social workers who acted as fieldworkers and who assisted with the analysis of the data: Dudley, M., Mhuka, M., Mkhize, N.R., Mkhonto, M., Monyela, R., Tsienyane, L.P. and Zikalala, N.

REFERENCES

AGEE, J. 2009. Developing qualitative research questions: a reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(4):431-447. [ Links ]

ALDRIDGE, J. 2014. Working with vulnerable groups in social research: dilemmas by default and design. Qualitative Research, 14(1):112-130. [ Links ]

AVIS, H. 2003. Drugs and life. United States of America: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

BARNARD, M. 2005. Drugs in the family: the impact on parents and siblings. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [ Links ]

BASKARADA, S. 2014. Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qualitative Report, 19(24):1-18. [ Links ]

BENSHOFF, J.J. & JANIKOWSKI, T.P. 2000. The Rehabilitation Model of Substance Abuse Counselling. London, U.K.: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

BURSTEIN, M. STANGER, C. & DUMENCI, L. 2012. Relations between parent psychopathology, family functioning, and adolescent problems in substance-abusing families: disaggregating the effects of parent gender. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 43:631-647. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL-PAGE, R.M. & SHAW-RIDLEY, M. 2013. Managing ethical dilemmas in community-based participatory research with vulnerable populations. Health Promotions Practice, 14(4):485-490. [ Links ]

CHAULKINS, J.P., KASUNIE, A. & LEE, M.A.C. 2014. Societal burden of substance abuse. International Public Health Journal, 6(3):269-282. [ Links ]

COPELLO, A.G., VELLEMAN, R.D.B. & TEMPLETON L.J. 2005. Family intervention in the treatment of alcohol and drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24:369-385. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2009. Research design - qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

D'CRUZ, H. & JONES, M. 2014. Social work research in practice: ethical and political contexts (2nd ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DENNING, P. 2010. Harm reduction therapy with families and friends of people with drug problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(2):164-174. [ Links ]

FEINBERG, M.E., SOLMEYER, A.R. & McHALE, S.M. 2012. The third rail of family systems: sibling relationships, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Childhood Family Psychology Review, 15:43-57. [ Links ]

FLORENCE, M. & KOCH, E. 2011. The difference between adolescent users and non-users of addictive substances in a low socio economic status community: contextual factors explored from the perspective of subjective well-being. South African Journal of Psychology, 41(4):477-487. [ Links ]

GIORDANO, G.N., OHLSSON, H., KENDLER, K.S., SUNDQUIST, K. & SUNDQUIST, J. 2014. Unexpected adverse childhood experiences and subsequent drug use disorder: a Swedish population study (1995-2011). Society for the Study of Addiction, 109:1119-1127. [ Links ]

GREEN, R.J. & THOROGOOD, N. 2009. Qualitative methods for health research (2nd ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GREENGLASS, E., FIKSENBAUM, L. & EATON, J. 2006. The relationship between coping, social support, functional disability and depression in the elderly. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 19(1):15-31. [ Links ]

GROVE, S.K., BURNS, N. & GRAY, J.R. 2013. The practice of nursing research. Missouri: Elsevier. [ Links ]

GUDZINSKIENE, V. & GEDMINIENE, R. 2010. Understanding of alcoholism as family disease. Socialinis Ugdymas, 14(25):163-172. [ Links ]

GUEST, G., NAMEY, E.E. & MITCHELL, M.L. 2013. Collecting qualitative data: a field manual for applied research. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HENNINK, M., HUTTER, I. & BAILEY, A. 2011. Qualitative research methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HITZEROTH, V. & KRAMER, L. 2010. Die einde van verslawing: 'n volledige Suid-Afrikaanse gids. Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

HOWARD, K.S., HESTON, J., KEY, C.M., McCRORY, E., SERNA-MCDONALD, C., SMITH, K.R. & HENDRICK, S.S. 2010. Addiction, the sibling, and the self. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15:465-479. [ Links ]

INCERTI, L., HENDERSON-WILSON, C. & DUNN, M. 2015. Challenges in the family. Problematic substance use and sibling relationships. Family Matters, 96:29-38. [ Links ]

JACKSON, D., USHER, K. & O-BRIEN, L. 2006-7. Fractured families: parental perspectives on the effects of adolescent drug abuse on family life. Contemporary Nurse, 23:321-330. [ Links ]

JESURAJ, M.J. 2012. Impact of substance abuse on families. Rajagiri Journal of Social Development, 4(2):33-44. [ Links ]

KIEBER, H.D., WEISS, R.D., ANTON, R.F., GEORGE, T.P., GREENFIELD, S.F., KOSTEN, T.R., O'BRIEN, C.P., ROUNSAVILLE, B.J., STRAIN, E.C., ZIEDONIS, D.M., HENNESY, G. & CONNERY, H.S. 2007. Treatment of patience with substance use disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(4):4-123. [ Links ]

KIRST-ASHMAN, K.K. 2013. Introduction to Social Work and Social Welfare: critical thinking perspectives. Canada: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

KRATHWOHL, D.R. 2009. Methods of educational and social sciences research: the logic of methods. Long Grove: Waveland Press. [ Links ]

KREFTING, L. 1991. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3):214-222. [ Links ]

LAZARUS, R.S. & FOLKMAN, S. 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [ Links ]

LICHTMAN, M. 2014. Qualitative research for the social sciences. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

LIETZ, C.A. & ZAYAS, L.E. 2010. Evaluating qualitative research for social work practitioners. Advances in Social Work, 11(2):188-202. [ Links ]

MARINUS, D.R. 2015. Adolescent's experiences and coping strategies with parental substance addiction within a rural farming community: a social work perspective. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Unpublished MA dissertation) [ Links ]

MATSIMBI, J.L. 2012. The perceptions, expectations, fears and needs of chemically dependent youth in a rehabilitation centre about being re-integrated into their family systems. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Unpublished MA dissertation) [ Links ]

MILLS, J. & BIRKS, M. 2014. Qualitative methodology: a practical guide. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

ORFORD, J., TEMPLETON, L., COPELLO, A., VELLEMAN, R., IBANGA, A. & BINNIE, C. 2009. Increasing the involvement of family members in alcohol and drug treatment services: The results of an action research project in two specialist agencies. Drugs, Education, Prevention and Policy, 16(5):379-408. [ Links ]

PADGETT, D.K. 2008. Qualitative methods in social work research (2nd ed). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

PERKINSON, R.R. 2008. Chemical dependency counselling: a practical guide. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2005. Children's Act (Act 38 of 2005). (Government notice 610 of 2005). Government Gazette28944. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2008. Prevention of and Treatment for Substance Abuse Act (Act 70 of 2008). (Government notice 436 of 2008). Government Gazette 526(32150). Cape Town: Government Printers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. Ministry for Welfare and Population Development. 1997. White Paper for Social Welfare. (Government notice 1108 of 1997). Government Gazette, 386 (18166). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RITCHIE, J. & LEWIS, J. 2005. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

SHENTON, A.K. 2004. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22:63-75. [ Links ]

SMITH, J.M. & ESTEFAN, A. 2014. Families parenting adolescents with substance abuse - recovering the mother's voice: a narrative literature review. Journal of Family Nursing, 20(4):415-441. [ Links ]

SURI, H. 2011. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal, 11(2):63-75. [ Links ]

TERRE BLANCHE, M., DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. 2006. Research in practice: applied methods for the social sciences (2nd ed). Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

UNGAR, M. 2003. Qualitative contributions to resilience research. Qualitative Social Work, 2(1):85-102. [ Links ]

USHER, K., JACKSON, D. & O'BRIEN, L. 2007. Shattered dreams: parental experiences of adolescent substance abuse. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16:422-430. [ Links ]

WEBBER, R. 2003. The impact of illicit drug use on non-using siblings in the Vietnamese community. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 38(2):229-245. [ Links ]

ZASTROW, C.H. & KIRST-ASHMAN, K.K. 2013. Understanding human behaviour and the social environment. United States: Brooks-Cole, Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

1 Chemical substance abuse, also interchangeably referred to as drug abuse, addiction or dependence, involves ongoing use of legal or illegal drugs in spite of their detrimental effects on the user's social, psychological, physical and spiritual wellbeing (Hitzeroth & Kramer, 2010:55-58; Kirst-Ashman, 2013:442-443).

2 This number of participants per field worker is the number as stipulated in the research module at fourth-year level, focusing on planning, executing and documenting the research process and findings.

3 The first author of this paper.

4 KZN = KwaZulu-Natal.