Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.51 no.2 Stellenbosch 2015

ARTICLES

Adolescents' lived experiences of their pregnancy and parenting in a semi-rural community in the Western Cape

Lenka van ZylI; Mariette van der MerweII; Shingairai ChigezaIII

IMA Student

IICentre for Child, Youth and Families Studies, Faculty of Health Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus

IIIAfrica Unit for Transdisciplinary Health Research (AUTHeR), North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This qualitative study aimed to illuminate the pregnancy and parenting experiences of adolescents from Sir Lowry's Pass Village in the Helderberg Basin. Participants were recruited through snowball sampling and participated in unstructured interviews. Findings highlight factors contributing to the pregnancies and the challenges participants experienced during pregnancy and parenting such as poverty, stigma, loss, and lack of parenting skills. The complexity of being a child in the house of their parents while having their own child is illuminated. Positive experiences include their children as source of meaning and the aspirations they have for their children.

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent pregnancy and parenting are a global phenomenon and have become a major cause of concern (Bezuidenhout, 2013:80). World Health Organisation (WHO) statistics indicate that worldwide about 16 million adolescents between the ages of 15 and 19, and about one million girls under the age of 15 give birth annually (WHO Fact Sheet, 2014). Recent South African statistics indicate that 12.4% of babies in South Africa are born to adolescents (Department of Social Development, 2012). The high rate of adolescent pregnancy has led to infant abandonment, which seems to occur mainly among young, single mothers, often under the age of 20, facing adverse economic, social and emotional circumstances (Davies, 2008:67; Herman-Giddens, Smith, Mittal, Carlson & Butts, 2003:1428). Several South African studies indicate that adolescents from underprivileged and often rural, coloured and black communities are at greater risk of adolescent pregnancy (Bezuidenhout, 2013:69; Jewkes, Morrell & Chistofides, 2009:678).

Adolescents often become parents without the necessary knowledge, skills and resources to deal with early parenthood, which adds stress to their already strenuous developmental level (Panday, Makiwane, Ranchod & Letsoalo, 2009:26). Adolescents frequently have to cope with the demands of parenthood, while integral developmental tasks have not yet been accomplished (Laghi, Baumgartner, Riccio, Bohr & Dhayanandhan, 2013:1074; Pungbangkadee, Parisunyakul, Kantaruksa, Sripchyakarn & Kools, 2008:71). Many of these adolescent parents perceive themselves as isolated, ostracised and unsupported during this difficult time (Bradley, 2003:109; Mwaba, 2000:31) and typically experience greater instability in relationships than their peers (Laghi et al., 2013:1075). Pregnancy and parenting further complicate adolescents' lives as it can lead to poverty, loss of freedom, disrupted education and compromised marriage prospects (Panday et al., 2009:27).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study was approached from the theoretical vantage points of community psychology (Lazarus, Bojuwoye, Chireshe, Myambo, Akotia, Mogaji, & Tchombe, 2006; Visser & Moleko, 2012), bio-ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Rosa & Tudge, 2013) and the mental health continuum (Keyes, 2002, 2005, 2007).

At the heart of community psychology is an aspiration to understand individuals within their social contexts and to provide interventions on various levels within their community so as to promote their wellbeing (Lazarus et al., 2006:147; Visser, 2012a:4). Community psychology attempts to share the knowledge of psychology with communities so that they might be empowered to steer their lives in a positive direction (Lazarus et al., 2006:147). The wellbeing of individuals is also promoted in other ways, such as the promotion of health and prevention of physical and mental illness; social change; focusing on compassion, caring and helping individuals to find a sense of belonging in their communities; and finding and building on individuals' strengths in order to foster empowerment of communities (Visser, 2012a: 11,12). One of the tenets of community psychology is to uplift and empower in particular marginalised individuals and communities (Visser, 2012a:14). The community psychology lens was therefore significant for this particular study, in that participants were from a deprived community, and the adolescent participants were viewed within their particular context.

Visser (2007:105) links Bronfenbrenner's theory of ecological systems with the social ecological model, which she outlines as a theoretical framework for community psychology. According to Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological systems theory, human development is continuously influenced by various interconnected, interacting environmental systems (Louw & Louw, 2014:29; Rosa & Tudge, 2013:246; Visser, 2012a:13). One of these systems is a temporal dimension, the chronosystem, according to which changes in the developing person, or the ecological contexts influencing development, can influence the direction development might take (Bronfenbrenner, 1994:40; Shaffer & Kipp, 2010:65). Keeping chronosystem theory in mind, the authors could consider how certain changes and different circumstances in adolescents' lives might have led up to their becoming pregnant, and how pregnancy and parenting influenced their lives from there onwards.

The focus of the mental health continuum is also on the wellbeing of individuals, and ties in well with the focus of community psychology. Keyes (2002:210) promotes the idea of a complete state, where symptoms of both mental health and mental illness are taken into account. A distinction is made between flourishing and languishing. Flourishing is a state of complete mental health, where an individual would be functioning well on psychological, emotional and social levels. In contrast, a languishing individual would display low levels of wellbeing, while a moderately mentally healthy individual could be described as neither languishing nor flourishing. On the pathology side of the continuum individuals could be viewed as either struggling or floundering. Struggling individuals may display some mental illness symptoms, but still exhibit relatively high levels of emotional wellbeing and positive functioning, while floundering individuals exhibit high levels of mental illness and low levels of emotional wellbeing and positive functioning (Venning, Wilson, Kettler & Eliott, 2013:300).

Keyes (2007:107) advocates such a complete state model with the eye to promoting individuals' wellbeing so that they might veer towards the flourishing end of the continuum. This theory was taken into account in the present study, as adolescent parents describing their experiences of early adolescent pregnancy and parenting could shed light on which experiences assisted them in veering towards the flourishing end of the mental health continuum, and what experiences they might need assistance with so as to steer them away from languishing, struggling and floundering.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Recent studies (Carvalho, Merighi & Jesus, 2010:473; Laghi et al., 2013:1079; Swartz & Bhana, 2009:105) have underscored the necessity for further research in the field of pregnant and parenting adolescents' experiences. When considering that 30% of South African adolescents under the age of 19 have been pregnant at least once (Louw & Louw, 2014: 318; Willan, 2013:4), it becomes imperative to explore their experiences so as to be better able to focus on their needs. The experiences of adolescent parents in South Africa are not fully understood, and the literature in this domain is scant (Department of Social Development, 2013; Panday et al., 2009:32, 41; Swartz & Bhana, 2009:4). In addition, pregnancy and parenting during adolescence are not merely a female event. Carvalho et al. (2010:473) point out that the situation cannot be resolved unless increased attention is given to male experiences of the phenomenon. Various studies have indicated that adolescent fathers can be an important source of support to adolescent mothers and their children (Fagan, Bernd & Whiteman, 2007:2; Macleod & Weaver, 2003:56), yet little information is available on adolescent fatherhood in the context of chronic poverty (Swartz & Bhana, 2010:4), as is so often the case in South Africa. According to Ratele (2012:277), poverty influences all aspects of life for individuals and communities. Poverty affects development, emotional and mental health, motivation, personality development and cognitions, in this way often trapping individuals in vulnerable circumstances.

Pregnant and parenting adolescents' circumstances and experiences need to be understood so as to provide them with appropriate assistance through programmes, health care and education, so that they might become better, more effective parents and cope adequately with their situation.

AIM

The aim of this study was to understand the lived experiences of pregnancy and parenting of adolescents in a semi-rural Western Cape community by using a phenomenological design.

RESEARCH QUESTION

The research question arising from the abovementioned problem statement is as follows: What are the lived experiences of adolescents in a semi-rural Western Cape community of their pregnancy and parenting?

METHOD

Research design

A qualitative approach and phenomenological design were utilised for this study. Qualitative approaches are useful in gaining insight into and describing the nature of participants' lived experiences in their life world (Fouché & Delport, 2011:65). Phenomenology entails attempts by researchers to capture participants' life worlds in a way that is not constraining or prescriptive (Henning, Van Rensburg & Smit, 2004:38) and to understand their psychological and social perspectives (Groenewald, 2004:5).

Participants' own views are important in that they can contribute towards appropriate interventions to a particular population (Daniels & Nel, 2009:62).

Phenomenology was the natural choice of design for this study, as a result of its social constructionist philosophical underpinnings, and theoretical paradigms such as community psychology and bio-ecological systems theory guiding the study. These theories, like phenomenology, all hold that the individual cannot be viewed in isolation, but should be considered within their particular contexts.

This research is explorative in nature, as the aim was to better comprehend late adolescents' experiences of pregnancy and parenting during early adolescence. Unstructured interviews were used to collect data to understand the lived experiences of adolescent parents.

Research context

In line with the phenomenological design, it is a premise of this study that human behaviour cannot be understood outside of the context in which people live (Welman, Kruger & Mitchell, 2005:191). Research has indicated that high crime and violence rates in conjunction with low levels of education, employment and income are strongly associated with early pregnancy and parenthood (Bezuidenhout, 2013:70, 73; Panday et al., 2009:39). Therefore Sir Lowry's Pass Village, a small, semi-rural community outside Somerset West in the Western Cape province of South Africa, was chosen as research context for this study. According to YourDictionary (2014), a semi-rural settlement is characterised by some country-like characteristics and is usually near farms. Residents of Sir Lowry's Pass Village are exposed to adverse circumstances, such as domestic violence, poverty, violent and sexual crimes, and drug and alcohol abuse (Helderberg Street People's Centre, 2010). During 2012 community members were involved in violent protests because of the inadequate service delivery in the area (Maditla, 2012). According to Ratele (2012:271), poverty not only entails lack of shelter, and inadequate nutrition and health care, but often goes hand in hand with powerlessness, a sense of failure, degradation and loss of hope. In this way, poverty has a negative influence on psychological wellbeing, which in turn could send an individual towards the languishing, struggling and floundering end of the mental health continuum. Importantly also, Terre Blanche (2008:314) points out that apart from the effects on mental health, the challenges presented by poverty and lack of opportunities should also be taken into account. These challenges include crowded environments, exposure to violence and poorly resourced services.

Participants

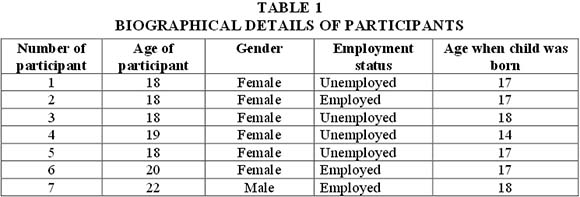

Snowball sampling was used in the study as late adolescent parents willing to share their pregnancy and parenting experiences was a hard-to-access group. Snowball sampling is specifically employed with hard-to-reach populations, and participants were recruited through referral by initial participants approached to investigate the phenomenon of interest (Strydom & Delport, 2011:393). As a result, six mothers and only one father from Sir Lowry's Pass Village between the ages of 18 and 22 (late adolescence) participated in the study. They reflected on their experiences of pregnancy and parenting during early adolescence (12-18). Because of the community's demographics, participants were from the coloured population group and Afrikaans speaking. Although themes were repeating in the data collected from participants, there was not a strong indication of data saturation. The first author found it difficult to involve participants and it is therefore a limitation of the study that findings were based on a limited number of participants, and only one adolescent father. However, as adolescent parents are a vulnerable group and also a hard-to-reach population, it was deemed important to reflect the voices of the participants who were available.

The biographical details of participants are shown in Table 1.

Data collection

Each participant was invited to participate in two in-depth, unstructured interviews. The experience of pregnancy during early adolescence was explored during the first interview, while parenting experiences in adolescence were explored during the second interview. In-depth interviews are best utilised when a phenomenological approach is followed to capture participants' reflexive accounts of their experiences in their own words (Henning et al., 2004:37). Additionally, a timeline activity was conducted with each participant in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the course of their lives. An upward and downward resource loss and gain spiral activity was also utilised to obtain a richer understanding of aspects of pregnancy and parenting that hampered and empowered participants. These activities can be viewed as a form of visual data collection, where drawings are used as a research tool in conjunction with verbal data-collection methods, and participants draw and write, or draw and talk (Mitchell, Theron, Stuart, Smith & Campbell, 2011:19). A final group discussion was held with four participants as a form of member checking, a technique whereby participants ensured that findings reflected their own experiences (Krefting, 1990:219). The adolescent father was not included in the group discussion, as he was the partner of one of the adolescent mothers participating in the group. The researcher did not want to compromise this couple's confidentiality. Interviews took place in a safe location, familiar to participants, so as to provide participants with a predictable, non-threatening environment.

Explicitation of data

Groenewald (2004:17) refers to the work of Hycner (1999), who cautions that the term "data analysis" is not congruent with phenomenology and suggests the term "explicitation" of data. Reading and re-reading transcripts of interviews form a basis to understand the phenomenon and to delineate and cluster units of meaning into themes as suggested by Groenewald (2004:17). The researchers endeavoured to keep their previous knowledge and experience apart from the data by bracketing.

Ethical considerations

The North-West University Human Research Committee approved this study. Participants were treated in a manner that is consistent with ethical conduct in that participant anonymity, privacy and confidentiality were maintained. Participants were adequately informed of the purpose of the study, and of possible risks, dangers and benefits of the study. They were also informed that participation was voluntary and how the results will be published, and that they could withdraw participation at any time, should they experience discomfort. They all gave written informed consent. Participants had the option to be referred to welfare organisations for further practical help or counselling.

FINDINGS

Participants reported that they found pregnancy and parenting to be challenging. In theme 1 factors contributing to pregnancy are outlined, regarding their particular vulnerability and lack of sex education. Challenges relating to pregnancy and parenting as described in theme 2 include poverty, lack of support, lack of parenting skills, stigma and loss. In theme 3 the complexity of being a child in the house of parents, while having a child, is discussed with reference to powerlessness and the fact that the parental rights of adolescent parents are not always respected. Theme 4 outlines the positive aspects regarding parenting, namely support, the children as source of meaning and the aspirations of participants for their children.

Theme 1: Factors contributing to adolescent pregnancy

The two sub-themes here are vulnerability and lack of sex education.

Sub-theme: Vulnerability

Loss of family members and poverty rendered participants vulnerable to adolescent pregnancy. All participants mentioned multiple socio-economic difficulties experienced during childhood and adolescence. Participants referred to circumstances involving lack of finances because of early deaths, or illness of significant family members. These factors contributed to the vulnerability of participants, ultimately leading to their becoming pregnant. Participant 2 shared that: "When I got older my mother got sick and the family began to tear apart, because there was no money and there was no one to look after my one brother and my one sister. I didn't really want a child. Just because those circumstances pushed me, I had to ... I just had to get pregnant." Similarly, other studies indicate that adolescent pregnancy rates are higher in disadvantaged communities in South Africa, especially among black and coloured women (Jewkes et al., 2009:678; Ngabaza, 2012:44).

Sub-theme: Lack of sex education

Some of the participants also indicated that lack of knowledge on sex education or advice from family members on issues around sex led them to fall pregnant. Participant 1 mentioned how she felt about the lack of support regarding sex education: "My sister, she didn't tell me I'd get pregnant and that I'd have children and all those things." Previous research indicates that there are still some gaps in imparting life skills and sex education to learners at schools and that implementation of effective programmes is irregularly distributed, not reaching all populations (MacLeod & Tracey, 2010:24).

Theme 2: Challenges related to adolescent pregnancy and parenting

Participants mentioned poverty, lack of support, lack of parental skills, stigma and loss as challenges faced by an adolescent parent during pregnancy and parenting.

Sub-theme: Poverty

The majority of the participants found that being a parent was challenging as a result of poverty. Participant 6 explained: "If maybe I don't have the finances then I must ask maybe my cousins or my aunts, and ask around for money, so it's kind of embarrassing ... then it seems I'm not mother-enough or something". Participant 5 similarly recounted: "When my child was 5 months old I took her off breast milk, because I got TB, then I had trouble ... my child milk. She must have porridge, and so, and I had a very hard time, because her father wasn't working full day then." It was a struggle for the participants to fulfil the subsistence needs of their babies. Poverty played a significant role in participants' lives in both physical and emotional domains. For some it gave rise to feelings of shame and embarrassment, in keeping with the low self-esteem often resulting from poverty (Ratele, 2012:269,278). Poverty and a lack of resources have been identified as the biggest obstacle to adolescent parenting in South Africa (Morrell, 2006:20; Swartz & Bhana, 2009:57).

Sub-theme: Lack of support from family and institutions

The majority of participants reported a general lack of support and feelings of isolation. Most prominent was the lack of familial support they experienced. Participant 5 explained the sense of isolation she had felt when her whole family turned against her:

"Most of them hated me and they didn't talk to me, or when they came there I went into the bedroom, then I'd go sit in the bedroom and lock the door. Then I'd sit there, and they'd all be inside there, they didn't worry about me."

Two participants were kicked out of their homes and had to turn to grandparents and the father of the child's family for survival. Participant 2 explained: "When he [older brother] got home that night he just told me to pack my things and leave. He doesn't want me there." Participant 4 similarly shared: "When they [parents] found out they didn't really do anything, except they told me I must leave the house, so I went to stay with my grandmother." Some of the young mothers also indicated a lack of support from the father of the child. Participant 6 said: "It's stressful ... especially when you are alone, when you are a single parent ... you have to fill the mother and the father's shoes. You have to be gentle, but you also have to be hard. You have to be able to discipline, but you also have to be the mother figure, so it's very stressful, really, and every month you must know it's only you that has to take care of the child, it's only you who have to ... the toiletries and the clothes and all those things" . The literature on adolescent parenting similarly reveals that mothers feel easily overwhelmed when having to juggle various roles without adequate support (Hanna, 2001:459).

Participant 6 shared how she also felt a lack of support in the hospital while in labour: "Yes, in my case ... they [hospital personnel] simply started ignoring me at one point. When I said I had pain, they didn't come. Maybe because we were still so young, maybe they were trying to teach us something, I don't know. But I lay there in pain. Even the doctor, I was yelling for the doctor, but they just walked past me. Some of them were drinking tea."

Even though some studies indicate that pregnant adolescents are well supported by their families (Logsdon, Birkimer, Ratterman, Cahill & Cahill, 2002:76; Macleod & Weaver, 2003:56), the results of this study seem to indicate that most participants felt unsupported in various ways during their pregnancies. This includes a lack of support from their families, which is problematic, as pregnant adolescents mostly rely on their nuclear families for support (Toomey, Umana-Taylor, Jahromi & Updegraff, 2013:205). Birkeland, Thompson and Phares (2005:297) and Holub, Kershaw, Ethier, Lewis, Milan and Ickovics (2007:153) believe that those who do not have adequate support, and experience high prenatal and parenting stress, are at an increased risk of emotional distress, which could lead them to struggle and flounder (Keyes, 2007:107).

Sub-theme: Lack of parenting skills

Participants indicated the pressure and anxiety felt about their inability to raise their children correctly, as information regarding their children's health care and discipline was not readily available to them. Participant 2 elaborated: "They don't really talk about such things, or give advice at hospitals and clinics; they would just tell you what to do

when you are there. Or you have to ask them 'What must I do here, or what must I do there?' When it happens, then they will tell you, but they won't just tell you out of their own."

Participant 6 explained how she often felt out of her depth when trying to discipline her child: "I just feel that when you are younger and you're a parent you don't have as much insight about ... you can't really create the boundaries, because it's almost like, you as parent also still have so much to learn." Participant 7 agreed: "Yes, it's also a bit difficult, because it's also my first child and I'm also still a young parent, so there's still a lot I have to learn." Bunting and McAuley (2004:301) indicated that a number of adolescent fathers do not receive adequate support from their families in learning about parenting. Similarly, adolescent mothers in a study by Daniels and Nel (2009:67) expressed that they did not have support from their mothers in this regard. It was clear that they did not always have good parenting examples in their own families.

Sub-theme: Stigma

During the interviews the adolescent parents recounted how their pregnancies were met with negative reactions and judgments, which frequently led to withdrawal from the outside world and ultimately exacerbated their sense of limited support and isolation. According to Bezuidenhout (2013:79), the families of adolescent parents, especially in small, rural communities, are often faced with stigmatisation and judgment. This seems to be similar in the semi-rural community of Sir Lowry's Pass Village.

Some participants recounted how gossiping about their pregnancies in the community, as well as judgment about their youth and the fact that they were sexually active, damaged their self-esteem and made them feel self-conscious. Participant 5 shared the stigma she was met with at the clinic: "At the clinic they always asked me, 'Girl, how old are you that you are having a child?'" Previous studies (De Jonge, 2001:53; Michels, 2000:558,563) have shown that pregnant and parenting adolescents neglect making proper use of health and social services, as they are keenly aware of the stigma some health and social services professionals attach to adolescent pregnancy, and therefore they feel disrespected and invaded when making use of these services.

Various participants complained about the judgment they experienced at school as well, from both teachers and peers. Participant 2 stated that: "my one teacher was very unhappy about it ... she just said she was very disappointed in me". In this regard participant 3 indicated that: "The teachers, when you enter the school, they look at you and they gossip, and when you get to class then they also gossip, the children. And if you go outside then there are people outside then they talk about you and you are pushed around in the courtyard" . Adolescent mothers in a South African study (Bhana, Clowes, Morrell & Shefer, 2008:81,82) have reported most teachers being moralistic and judgmental, and that they are permitted to attend school as a matter of course and law only. Teachers do not usually make any special efforts to support them, and mostly view them as poor role models for their peers. However, the study by Bhana et al. (2008:88) found some female teachers to be supportive, unlike the experience reported by some of the participants in this study.

Some participants also recounted how community members judged their parenting practices, called them bad mothers, or talked about them behind their backs. Participant 4 shared: "People outside my family can only do bad things, or say bad things. Everyone says I'm not a good mother, or something, but I make time" . Other studies similarly indicated that pregnant and parenting adolescents are frequently stigmatised by the school, their parents, community members and nursing staff (Breheny & Stephens, 2007:122; Jewkes et al., 2009: 680,682; Ngabaza, 2010:47).

Sub-theme: Loss

Adolescent parents also reported a sense of loss on different levels. Participant 6 elaborated on the loss of educational opportunities: "I was in standard nine, halfway through standard nine. And all my mother said was 'You wanted to be an adult, we don't keep adults in school, you have to leave school'. Then I left school" . This is in line with findings that adolescent mothers are less likely to complete their education than their older counterparts as a result of adolescent pregnancy (Macleod & Weaver, 2003:50). While some adolescent mothers in this study left school as a result of their pregnancies, this was not the case for participant 7. He shared: "I left school in Grade 10, you know? I thought I want to leave school and bring in bread for my mother as well." In this particular study participant 7, being the only adolescent father in the study, left school early as result of having to replace his father, who left them, as the breadwinner. However, Swartz and Bhana (2009:25) indicate that some adolescent males leave school as a result of adolescent pregnancy. They are in the difficult position of having to accept underpaid jobs at the cost of their education so as to provide for their children. Furthermore, these young men seldom make it back into the education system (Swartz & Bhana, 2009:25), which could in turn trap them in the cycle of poverty. In this way they are prevented from reaching their full potential and the possibility of rising above their adverse circumstances (Daniels & Nel, 2009:62).

Some participants referred to the loss of their freedom. When they fell pregnant, they often had to give up a previous lifestyle to look after their children. Participant 6 explained how she felt she had to sacrifice her youth and free time: "Everything about being young. My free time. I couldn't hang with my friends like I could before. I had more responsibilities. Uhm .. .my me-time isn't me-time at all." Participant 7 related how he had felt propelled into adult life, leaving his youth behind: "Your childhood is now over, you're an adult now." This is in keeping with findings by Carvalho et al. (2010:471), where adolescent fathers mentioned the loss of leisure time as a result of becoming a father, as well as feeling forced into adulthood.

Theme 3: Complexity of still being a child within the family

Participants experienced the complexity of still being a child within the family. It seemed as if the majority of the adolescents' parents still regarded them as children and did not respect their views. This created a complex dynamic which caused participants to experience that their views were not respected and made them feel powerless.

Sub-theme: Powerlessness

Participants explained during interviews how they experienced a great sense of powerlessness, revolving around issues such as lack of control in their lives and being denied the right to make choices for themselves and their children.

Powerlessness resulted when parents of adolescents did not allow their children to make their own choices. Participant 6 described how her family kept her child from seeing her father, even though she realised how important this was for her daughter: "If my boyfriend had a year of contact with my child, then it was a lot, because the moment he did something bad he couldn't see her. And if they should hear in that time he wasn't allowed to see her that we'd had contact, they'd throw my phone against the wall". Similarly previous studies have indicated that some adolescent fathers want to be part of their children's lives, but are shunned by the adolescent mother's family (Panday et al., 2009:7; Swartz & Bhana, 2009:62). Conversely, in other studies adolescent mothers were of the opinion that adolescent fathers' lack of involvement is the result of lack of interest (Bunting & McAuley, 2004:295; Weinman, Smith & Buzi, 2002:439). Dallas (2004:351) mentions that families often lack guidelines on how to negotiate joint support when the father of the child and his family also want to be a part of the child's life, in this way frequently depriving adolescent parents of an additional source of support. Participant 2 also recounted how her family denied her choice and control. They wanted to send her away and give her baby up for adoption upon finding out about her pregnancy, not allowing her any choice in the matter: "They just told me they would, when I'm done, they would first send me away, as soon as I'm done, and then they'd take her and give her to other people." Statements such as this draw attention to the complexity of being a child in one's parents' home, while also having to assume the role of parent. Pungbangkadee et al. (2008:71) draw attention to the fact that adolescents naturally veer towards independence, while adolescent pregnancy and parenthood, in contrast, necessitate dependence on parents.

Sub-theme: Parental rights are not respected

Participants indicated that their parental rights were not respected, especially by family members. Participant 3 explained how her sister simply assumed that she could not take care of her child and took him away from her: "I feel if he was with me she could still help him. I don't mind her helping, but the child must stay with me as well."

Participant 6 shared how she felt when her parents continuously undermined her disciplining strategies: "One almost feels you're not worthy of being the child's mother and just like ... you just feel they must stand back a bit." In a study by Swartz and Bhana (2009:61) on adolescent fathers it became apparent that when mothers of adolescent parents take too much responsibility for their children's babies, they deny them the opportunity to reach independence and responsibility.

Theme 4: Positive aspects related to adolescent pregnancy and parenting

Adolescent parents also mentioned positive aspects related to parenting in terms of support they got from family members and professional health care. They also described their children as the source of joy and meaning in their lives. The meaning and joy experienced from their children enabled them to develop a positive attitude about their lifestyles and world views. Some the participants expressed their aspirations for their children.

Sub-theme: Support

Pregnancy and parenting seemed significantly easier in cases where participants experienced some form of support. Participant 6 explained that: "it's difficult... so if you get support from outside it helps the situation. But I ... all I can say is, I received a tremendous amount of support, from my aunt, my friends at church, and even from my boyfriend's parents. That helped, even though I received no support in my own home." Several participants did not receive adequate support from their nuclear families, but found support through different avenues, such as from other family members, the father of their child, his family, or the church. Participant 5 shared the following about her child's father: "He works when he can, he buys when he can, does everything, when I ask him something he would give me everything, even when he has to give me his last, he'd give it to me." Participant 7 felt supported by the mother of his child, as well as his family: "My mother, father, uncle, aunt... anything we needed, we could just depend on them."

In a study by Swartz and Bhana (2009:58) adolescent fathers indicated that they felt mostly supported by their mothers. General support from family members regarding caring for the child and taking over some child-care responsibilities so that the adolescent father can do what is necessary (for instance, work to provide financially) is also experienced by them in a positive way (Carvalho et al., 2010:472). Most participants in this study emphasised the importance of practical and financial support. Participant 2 related how her sister-in-law's parenting advice had been invaluable: "My sister-in-law talked to me about it a lot, how it's going to be when I'm a mother, how it's going to be when you finish, and what you need to do, and those things." Participant 4 underscored the importance of the clinic's material contributions: "Look, later I didn't even have to buy milk, I got it at the clinic. I get it for free."

Sub-theme: Children as source of meaning

Participants also mentioned some positive aspects related to parenting, such as finding children a source of comfort and meaning in their lives. In addition, participants who received support developed a positive attitude about their lifestyles and world views. Keyes (2005:540) indicated that individuals' subjective wellbeing, their perceptions of their lives and the quality of their functioning contribute to mental health.

Participants emphasised the importance of their relationship with their children and how they bring joy and meaning into their lives. Participant 6 shared: "It's just so wonderful to know, at the end of the day, especially when you've had a stressful day, and you come home, you can know that that's the one person who will give you sincere love and come to you with a kiss or a hug and kind of make you feel better when the world doesn't make sense anymore." Participant 5 explained how her child reduced her sense of loneliness: "It's like ... still nice to be at home, just to give your child love. I don't worry about the people on the streets, or friends, I have my own friend now." Participant 7 shared how seeing his child asleep when going to work fills him with a sense of wonder: "for me it's ... it's such a feeling that comes over you, to be able to say, joh, this is my child" . Participant 4 noted: "Goodness, but many things changed ... and how I see the world. It's now not just... every day isn't just a big joke, or we just go into life. It's almost like a privilege for me now, to open my eyes each day, because many things ... more things have become important, it's not just a party all the time." Participants found the experience of parenting significant in that they felt it changed their views on and attitudes to life, rendering them more mature, more responsible individuals. This is consistent with previous research, where adolescent parents mentioned the transformative effect of parenting (Carvalho et al., 2010:471; Dornig et al., 2009:55; Swartz & Bhana, 2009:39). Participant 2 stated: "today I think more like an adult than two years ago. And the way I do things is also completely different from two years ago. I used to do a lot of things ... I broke into people's homes. I almost went to jail". Dornig et al. (2009:55), Lesser, Anderson and Koniak-Griffin (1998), Seamark and Lings (2004:817) state that children bring a greater sense of purpose and hope for the future to adolescent parents.

Sub-theme: Aspirations for their children

Participant 2 expressed wanting a different life for her child to what she had had: "Almost like, she mustn't walk the path I walked." This is similar to previous studies indicating that adolescent parents often want to give their children what their own parents had failed to provide for them (Dornig et al., 2009:56; Lesser et al., 1998:11; Seamark & Lings, 2004:815). This could include, for instance, the attention, guidance and love they did not receive from their own parents (Lesser et al., 1998:11; Seamark & Lings, 2004:815); avoiding parenting mistakes their parents had made; and a wish that their children would have better lives than they had, by proactive planning for their children, and making sure they get a good education (Dornig et al., 2009:56).

DISCUSSION

Participants in this study indicated that pregnancy and parenting during early adolescence were predominantly challenging experiences. Almost all participants indicated that vulnerability and lack of sex education contributed in some way or another to their becoming pregnant and complicated their parenting experiences. According to Jewkes et al. (2009:682), it is essential to view adolescents within their environmental context and to consider how the way in which they were socialised plays a role in their becoming pregnant. This is in line with the way in which the research was conducted, viewing adolescent parents' experiences with community psychology and bio-ecological systems theories in mind. These theories allowed the authors to view adolescent parents within the context of their environmental fields in order to understand their experiences of pregnancy and parenting optimally. These parents' contexts involved, among other things, socio-economic difficulties and inadequate support systems, which were amplified by the experiences of pregnancy and parenting. From a community psychology perspective, such a view of individuals within their context provides a more comprehensive view of their needs and problems (Lazarus et al., 2006:147), which in turn relates to the mental health continuum in that such information could assist social and health service professionals with the necessary service provision to this population; this could in turn promote flourishing (Keyes, 2005:547). In line with bio-ecological systems theory, this study shed light on proximal processes and how participants' personal characteristics, paired with certain environmental factors and changes, had an impact on the course of their development. In chronosystem terms, some participants experienced what could be described as non-normative or unexpected changes, such as the serious illness or death of a close family member, which in turn influenced the course of their life and development in that certain adverse circumstances contributed to adolescent pregnancy (Rosa & Tudge, 2013:250).

Adolescent parents experienced pregnancy and parenting as mostly difficult as a result of stigma from families, peers and others; feelings of isolation and being ostracised; the loss of various important things, such as their freedom, educational possibilities and friends; and a general lack of support. These findings are supported in the literature about the negative experiences of adolescent pregnancy and parenting involving stigma, loss and rejection (Hanna, 2001:459; Ngabaza, 2011:47,49). As Keyes (2002:209) noted, not feeling part of a community and not feeling accepted impacts negatively on social wellbeing and could contribute to participants' leaning towards the languishing, struggling or floundering end of the mental health continuum. Toomey et al. (2013:195) hold that support is a buffering factor in adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Orford (1994:75) similarly contends that individuals are buffered by the presence of social support during major life changes, or in times of crisis. Additionally, the literature has highlighted the importance of supportive relationships as a significant contributing factor to the wellbeing of pregnant adolescents (Kershaw et al., 2013:288).

Some participants in this study lacked support from their mothers, who were not involved during their pregnancy and parenting, contrary to other studies indicating that families were supportive during adolescents' pregnancies (Logsdon et al., 2002:76; Macleod & Weaver, 2003:56). Sometimes this lack of support was because their mothers had passed away, were ill, disapproved of their pregnancies, or were abusing alcohol. This lack of support from mother figures is disconcerting, as the literature suggests that the role of mothers during their adolescent children's pregnancies is paramount, as their support in particular has the potential to promote wellbeing and reduce risks related to adolescent pregnancy (Jewkes et al., 2009:681; Toomey et al., 2013:195). Female participants also felt unsupported in the sense that their relationships with the fathers of their children were often disapproved of, and family members frequently tried to keep them from what Kershaw et al., (2013:299) view as a potentially significant source of support. Some South African studies have indicated that adolescent mothers need more emotional support from parents and sorely miss peer and partner support (De Visser & Le Roux, 1996; Parekh & De la Rey, 1997). Adolescent fathers, in turn, have expressed a need for increased support in the practical and informational spheres (Swartz & Bhana, 2009:94,96). Research indicates that it is important to assist fathers to form a part of their children's lives, as they contribute to their children's wellbeing in unique ways (Spjeldnaes, Moland, Harris & Sam, 2011:7).

In accordance with bio-ecological systems theory, proximal processes have a better chance of influencing development positively in environments which are stable and advantageous, as well as among individuals with strong emotional connections (Rosa & Tudge, 2013:252). Therefore, it is understandable that factors such as poverty, and tenuous relationships and support, influenced participants' development, as well as their experience of pregnancy and parenting.

Participants reported being stigmatised by community members, teachers, peers and hospital and clinic staff. Specifically with regard to health professionals, Breheny and Stephens (2007:122) warn against their drawing upon certain dominant discourses about adolescent pregnancy and parenthood, such as adolescent mothers automatically being 'bad mothers', or incompetent parents, as these discourses are mostly negative in nature and do not draw upon adolescents' individual strengths, which in turn makes these young mothers distrustful of and negative towards the health care system, and they fail to empower them.

The participants in this study felt the pressures of parenting keenly and frequently reported feeling overwhelmed. Participants expressed a need for more information and guidance around parenting skills, rather than having to cope with the high expectations and judgments from those around them about their current parenting practices. Swartz and Bhana (2009:87) mention that adolescent fathers generally find programmes centring on parenting helpful. Furthermore, participants felt that their parental rights were often not respected, as their elders took over child-care responsibilities, or undermined their disciplining strategies, which illuminate some of the complexities of being a child in the home of parents, while also having to raise one's own young child. Clearly participants were also not given the chance to learn how to be parents to their children and to take responsibility for their own and their children's lives. This is similar to findings in Swartz and Bhana's (2009:61) study, which indicate that adolescent father's mothers at times take responsibility to the extent that adolescent fathers end up regarding their children as siblings. Such attitudes towards taking responsibility might stifle adolescent parents' sense of self-efficacy and personal control, which might in turn compromise their sense of empowerment (Visser, 2012a:12). According to Visser (2012a:12), empowering individuals revolves around believing in, and encouraging, their capacity to resolve their own difficulties, and it is one of the key elements promoted by community psychology.

Negative experiences of pregnancy and parenting seemed to be mitigated by the perceived significance of adolescent parents' relationships with their children, the meaning they found in being a parent, and the support they received. Research indicates that interpersonal relationships providing a sense of belonging are vital contributions to mental health (Keyes, 2005:547). Participants seemed to view themselves as more mature, responsible adults as a result of becoming parents, and life as being precious and a privilege. This concurs with participant 7's life changes, involving, for instance, not stealing any longer. Even though participants expressed a distinct awareness of the hardships involved in adolescent pregnancy and parenting in some of the themes, they also expressed positive thoughts and feelings about it. Keyes (2005:540) believes that such positive feelings about one's life contribute significantly to mental health, and the possibility of an individual flourishing as opposed to languishing, floundering, or struggling. Participants also described their relationships with their children as a significant, supportive factor in their lives, providing them with comfort. They frequently commented on their wishes for their children, and the gravity with which they approached the tasks of protecting, disciplining and communicating values to their children. Weinman, Buzi and Smith (2005:265) highlight the importance of emphasising adolescent parents' strengths in order to empower them sufficiently to make progress. These positive experiences of parenting could be utilised in interventions with adolescent parents so that they may move towards the flourishing end of the mental health continuum.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Participants in this study showed a tenacity and a will to survive that, if properly channelled and guided, could improve their own and their children's quality of life considerably. Dornig et al. (2009:58) pointed out in a recent study that adolescent pregnancy and parenthood might be an important moment of hopefulness during which to enter into and channel these young individuals' lives in positive ways. The meaning of having a child for adolescent parents could be a focus of further research, especially as it may be one of the factors involved in why they become pregnant.

Participants communicated a lack of support and knowledge in various areas of their lives. Therefore, linking pregnant and parenting adolescents with the appropriate resources and sources of support, such as hospitals, clinics, and welfare and counselling services, is of vital importance.

Adolescent parents communicated feelings of isolation, especially during the pregnancy period. Lack of support from mother figures in particular was frequently experienced. Thus it is important to help adolescent parents connect with figures they can look to for guidance and emotional support, such as parents, counsellors or therapists.

Groups for pregnancy and parenting support, therapy and parent education could be set up in semi-rural communities. Participants in this study communicated a need for such emotional and informational support. Self-help groups could also be considered for pregnant and parenting adolescents. These groups reflect many of the attitudes inherent in community psychology, as they could be viewed as indigenous resources that empower individuals, in this way aiding in the prevention and resolution of problems. These groups could provide a sense of belonging and additional support to members, while the resulting empowerment and heightened sense of support could in turn lead to increased wellbeing and flourishing.

Furthermore, accessible programmes centring on sex education could prevent further pregnancies among adolescent parents, as the parents in this study also indicated a lack of knowledge in this area. While it has been proposed that such programmes presented in schools are not accessible enough for learners it is also possible that adolescent parents, as a result of their socio-economic circumstances, do not reach the grades in school at which point sex education is provided. Programmes presented in the community, also involving peer-to-peer sex education, could benefit the difficult-to-reach adolescent parent population group.

Additional support for the families of pregnant and parenting adolescents should be provided, as it became apparent in this study that these adolescents' families often do not know how to handle the news of their pregnancies, struggle to involve their adolescent child's partner for support, or are already in crisis and requiring outside help. Family therapy group sessions could benefit these family structures greatly. In some cases therapeutic family mediation can secure the positive involvement of adolescent parents, their parents, family members and friends. Therapeutic family mediation in the context of adolescent pregnancy and parenting warrants research.

Adolescent parents also communicated the negative impact of stigmatisation. Consequently psycho-education on adolescent pregnancy and the circumstances surrounding the phenomenon could be presented in schools and to clinic and hospital staff, to promote acceptance and support and minimise stigma. Negative discourses and stereotypes about adolescent pregnancy and parenting should be addressed during information sessions presented to clinic and hospital staff, ensuring that psycho-education covers the necessity for health care professionals to draw on pregnant and parenting adolescents' strengths rather than focussing on deficits and problems.

Furthermore, actions such as throwing a phone against a wall are indicative of a lack of communication and problem-solving skills. Such skills could be facilitated in family sessions with adolescent parents and their families. Therapeutic family mediation as outlined by Irving and Benjamin (2002) could be of value to these families. Further research on this mode of intervention should be conducted.

As only a limited number of participants was involved in this study, it is suggested that more research around the experiences of minority group adolescent parents should be done in South Africa with larger sample sizes, with a specific focus on the experiences of adolescent fathers.

CONCLUSION

This study promotes understanding of the lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents as informed and shaped by their environments. Participants indicated that they found pregnancy and parenting trying as a result of their socio-economic circumstances, feelings of powerlessness and loss, stigmatisation, and lack of support. Their parenting was affected by their lack of parenting skills. Furthermore, their parental rights were frequently not respected. However, parenting was not an altogether negative experience, as they indicated that the comfort of having children, support from others, and the transformative effect of parenthood were positive experiences. This deeper understanding of adolescent pregnancy and parenthood enables pathways in interventions in aid of this vulnerable population group. Such interventions could include support, therapy and self-help groups for pregnant and parenting adolescents; adequate sex education presented in schools and the community; therapeutic family mediation, support and psycho-education for parents of pregnant and parenting adolescents; as well as psycho-education in schools, clinics and hospitals to minimise potential stigma.

REFERENCES

BEZUIDENHOUT, F.J. 2013. A reader on selected social issues. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

BHANA, D., CLOWES, L., MORRELL, R. & SHEFER, T. 2008. Pregnant girls and young parents in South African schools. Agenda, 76:78-90. [ Links ]

BIRKELAND, R., THOMPSON, J.K. & PHARES, V. 2005. Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(2):292-300. [ Links ]

BRADLEY, D. 2003. Perspectives on newborn abandonment. Pediatric Emergency Care, 19(2):108-111. [ Links ]

BREHENY, M. & STEPHENS, C. 2007. Irreconcilable differences: health professionals' constructions of adolescence and motherhood. Social Science & Medicine, 64:112-124. [ Links ]

BRONFENBRENNER, U. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In: International Encyclopedia of Education, 3:1643-1647. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

BUNTING, L. & McAULEY, C. 2004. Research review: teenage pregnancy and parenthood: the role of fathers. Child and Family Social Work, 9:295-303. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, G.M., MERIGHI, M.A.B. & JESUS, M.C.P. 2010. The experience of repeated fatherhood during adolescence. Midwifery, 26:469-474. [ Links ]

DALLAS, C. 2004. Family matters: how mothers of adolescent parents experience adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Public Health Nursing, 21(4):347-353. [ Links ]

DANIELS, D. & NEL, E. 2009. Tienermoederskap in 'n arm Wes-Kaapse gemeenskap: Narratiewe oor ondersteuning. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 45(1):62-75. [ Links ]

DAVIES, L. 2008. Mothers who kill their children. A literature review. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. (Unpublished MA thesis) [ Links ]

DE JONGE, A. 2000. Support for teenage mothers: a qualitative study into the views of women about the support they received as teenage mothers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(1):49-57. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2012. White Paper on Families in South Africa, 1-63. [ Links ]

DE VISSER, J. & LE ROUX, T. 1996. The experience of teenage pregnancy in Knoppieslaagte. South African Journal of Sociology, 27(3):98-106. [ Links ]

DORNIG, K., KONIAK-GRIFFIN, D., LESSER, J., GONZÁLEZ-GIGUEROA, E., LUNA, M.C., ANDERSON, N.L.R. & COREA-LONDON, B. 2009. "You gotta start thinking like a parent": hopes, dreams, and concerns of ethnic minority adolescent parents. Families in Society, 90(1):51-60. [ Links ]

FAGAN, J., BERND, E. & WHITEMAN, V. 2007. Adolescent fathers' parenting stress, social support and involvement with infants. Journal of Research on Adolescents, 17(1):1-22. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 307-327. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2011. Introduction to the research process. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 61-76. [ Links ]

GROENEWALD, T. 2004. A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1). [ Links ]

HANNA, B. 2001. Negotiating motherhood: the struggles of teenage mothers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(4):456-464. [ Links ]

HELDERBERG STREET PEOPLE'S CENTRE. 2010. History of Sir Lowry's Pass. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.helderbergstreetpeople.co.za/ [Accessed: 12/06/2011].

HENNING, E., VAN RENSBURG, W. & SMIT, B. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

HERMAN-GIDDENS, M.E., SMITH, J.B., MITTAL, M., CARLSON, M. & BUTTS, J.D. 2003. Newborns killed or left to die by a parent: a population-based study. JAMA, 289(11):1425-1429. [ Links ]

HOLUB, C.K., KERSHAW, T.S., ETHIER, K.A., LEWIS, J.B., MILAN, S. & ICKOVICS, J.R. 2007. Prenatal and parenting stress on adolescent maternal adjustment: identifying a high-risk subgroup. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11:153-159. [ Links ]

IRVING, H.H. & BENJAMIN, M. 2002. Therapeutic family mediation. Helping families resolve conflict. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

JEWKES, R., MORRELL, R. & CHRISTOFIDES, N. 2009. Empowering teenagers to prevent pregnancy: lessons from South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(7):675-688. [ Links ]

JOOSTE, B. 2010. City's dumped baby shame. Cape Argus. 16 August. [ Links ] [Online] Available http://www.samedia.uovs.ac.za.ez.sun.ac.za/cgibin/getpdf?year=2010& refno =3915&topic=10 [Accessed: 29/04/2011].

KERSHAW, T., MURPHY, A., DIVNEY, A., MAGRIPLES, U., NICCOLAI, L. & GORDON, D. 2013. What's love got to do with it: Relationship functioning and mental and physical quality of life among pregnant adolescent couples. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52:288-301. [ Links ]

KREFTING, L. 1990. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3):214-222. [ Links ]

KEYES, C.L.M. 2002. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 43(2):207-222. [ Links ]

KEYES, C.L.M. 2005. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3):539-548. [ Links ]

KEYES, C.L.M. 2007. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing. American Psychologist, 62(2):95-108. [ Links ]

LAGHI, F., BAUMGARTNER, E., RICCIO, G., BOHR, Y. & DHAYANANDHAN, B. 2013. The role of romantic involvement and social support in Italian adolescent mothers' lives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22:1074-1081. [ Links ]

LAZARUS, S., BOJUWOYE, O., CHIRESHE, R., MYAMBO, K., AKOTIA, C., MOGAJI, A. & TCHOMBE, T. 2006. Community psychology in Africa: views from across the continent. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 16(2):147-160. [ Links ]

LESSER, J., ANDERSON, N.L.R. & KONIAK-GRIFFIN, D. 1998. "Sometimes you don't feel ready to be an adult or a mom": the experience of adolescent pregnancy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 11(1):7-16. [ Links ]

LOGSDON, M.C., BIRKIMER, J.C., RATTERMAN, A., CAHILL, K. & CAHILL, N. 2002. Social support in pregnant and parenting adolescents: research, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 15(2):75-83. [ Links ]

LOUW, D.A. & LOUW, A.E. 2014. Child and Adolescent Development. Bloemfontein: Psychology Publications. [ Links ]

MACLEOD, C.I. & TRACEY, T. 2010. A decade later: follow-up review of South African research on the consequences of and contributory factors in teen-aged pregnancy. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(1):18-31. [ Links ]

MACLEOD, A.J. & WEAVER, S.M. 2003. Teenage pregnancy: attitudes, social support and adjustment to pregnancy during the antenatal period. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 21(1):49-59. [ Links ]

MADITLA, N. 2012. Village sealed off by protest. Cape Argus, 9 May. [ Links ] [Online] Available http://www.iol.co.za/news/crime-courts/village-sealed-off-by-protest-1. 12927 80#.U0ecifmSz-s [Accessed: 20/01/2013].

MICHELS, T.M. 2000. "Patients like us": pregnant and parenting teens view the health care system. Public Health Reports, 115:557-575. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, C., THERON, L., STUART, J., SMITH, A. & CAMPBELL, Z. 2011. Drawings as research method. In: MITCHELL, C., THERON, L., STUART, J. & SMITH, A. (eds) Picturing research: drawing as visual methodology. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

MORRELL, R. 2006. Fathers, fatherhood and masculinity in South Africa. In: RICHTER, L. & MORRELL, R. (eds) Baba: men and fatherhood in South Africa. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

MWABA, K. 2000. Perceptions of teenage pregnancy among South African adolescents. Health South Africa, 5(3):30-34. [ Links ]

NGABAZA, S. 2011. Positively pregnant: teenage women's experiences of negotiating pregnancy with their families. Agenda: Empowering women for gender equity, 25(3):42-51. [ Links ]

NOLEN-HOEKSMA, S., FREDRICKSON, B.L., LOFTUS, G.R. & WAGENAAR, W.A. 2009. Atkinson & Hilgard's Introduction to Psychology (15th ed). Hampshire: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

ORFORD, J. 1994. Community psychology: theory and practice. New York. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

PADGETT, D.K. 2008. Qualitative methods in social work research (2nd ed). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

PANDAY, S., MAKIWANE, M., RANCHOD, C. & LETSOALO, T. 2009. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: with a specific focus on school-going learners. Child, Youth, Family and Social Development, Human Sciences Research Council. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

PAREKH, A. & DE LA REY, C. 1997. Intragroup accounts of teenage motherhood: a community based psychological perspective. South African Journal of Psychology, 27(4). [ Links ] [Online] Available http://www.iournals.co.za/ei/eiour sapsyc.html [Accessed: 02/02/2011].

PUNGBANGKADEE, R., PARISUNYAKUL, S., KANTARUKSA, K., SRIPCHYAKARN, K. & KOOLS, S. 2008. Experiences of early motherhood among Thai adolescents: perceiving conflict between needs as a mother and an adolescent. Thai Journal of Nursing Research, 12(1):70-82. [ Links ]

RATELE, K. 2012. Poverty and inequality. In: VISSER, M. & MOLEKO, G. Community Psychology in South Africa (2nd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 4154. [ Links ]

ROSA, E.M. & TUDGE, J. 2013. Urie Bronfenbrenner's theory of human development: its evolution from ecology to biology. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5:243258. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 397-423. [ Links ]

SEAMARK, C.J. & LINGS, P. 2004. Positive experiences of teenage motherhood: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice, 54:813-818. [ Links ]

SHAFFER, D.R. & KIPP, K. 2010. Developmental psychology: childhood and adolescence (8th ed). Belmont: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

SPJELDNAES, I.O., MOLAND, K.M., HARRIS, J. & SAM, D.L. 2011. Being man enough: fatherhood experiences and expectations among teenage boys in South Africa. Fathering, 9(1). [ Links ]

SWARTZ, S. & BHANA, A. 2009. Teenage Tata: voices of young fathers in South Africa. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press. [ Links ]

TERRE BLANCHE, M. 2008. Poverty. In: SWARTZ, L., DE LA REY, C., DUNCAN, N. & TOWNSEND, L. Psychology. An introduction (2nd ed). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

TOOMEY, R.B., UMANA-TAYLOR, A.J., JAHROMI, L.B. & UPDEGRAFF, K.A. 2013. Measuring social support from mother figures in the transition from pregnancy to parenthood among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 35(2):194-212. [ Links ]

VENNING, A., WILSON, A., KETTLER, L. & ELIOTT, J. 2013. Mental health among youth in South Australia: a survey of flourishing, languishing, struggling and floundering. Australian Psychologist, 48(4):299-310. [ Links ]

VISSER, M. 2007. The social ecological model as theoretical framework in community psychology. In: DUNCAN, N., BOWMAN, B., NAIDOO, A., PILLAY, J. & ROOS, V. (eds) Community psychology: analysis, context and action. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

VISSER, M. 2012a. Community psychology. In: VISSER, M. & MOLEKO, A. (eds) Community psychology in South Africa (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 219. [ Links ]

VISSER, M. 2012b. Social support as a community resource. In: VISSER, M. & MOLEKO, A. (eds) Community psychology in South Africa (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 127-145. [ Links ]

WEINMAN, M.L., BUZI, R.S. & SMITH, P.B. 2005. Addressing risk behaviours, service needs, and mental health issues in programs for young fathers. Families in Society, 86(2):261-266. [ Links ]

WEINMAN, M.L., SMITH, P.B. & BUZI, R.S. 2002. Young fathers: An analysis of risk behaviors and service needs. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 19:437-453. [ Links ]

WELMAN, C., KRUGER, F. & MITCHELL, B. 2005. Research methodology (3rd ed). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

WILLAN, S. 2013. A review of teenage pregnancy in South Africa - experiences of schooling, and knowledge and access to sexual and reproductive health services. Partners in Sexual Health. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.hst.org.za/ sites/default/files/Teenage%20Pregnancy%20in%20South%20Africa %20Final%2010% 20May%202013.pdf [Accessed: 17/02/2014].

WHITTAKER, A. 2012. Research skills for social work. Glasgow: Learning Matters. [ Links ]

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION FACT SHEET. 2014. Adolescent pregnancy. [ Links ] [Online] Available http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en/ [Accessed: 12/02/2015].

YOURDICTIONARY. 2014. Semirural. [ Links ] [Online] Available http://www.yourdictionary.com/semirural [Accessed: 28/09/2014].