Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.51 n.2 Stellenbosch 2015

http://dx.doi.org/51-1-448

ARTICLES

The effect of dissolved workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved

Hendrika VerhoefI; Lourie TerblancheII

IPostgraduate student

IIDepartment of Social Work and Criminology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. lourie.terblanche@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This paper reports on research that explored the effects of dissolved romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved at an industrial clothing factory in Cape Town in 2012-2013. Also explored is the consequent need for appropriate intervention through the existing Employee Assistance Programme (EAP). A qualitative research approach is applied. The main conclusion confirms the overall negative effect of the breakdown of workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved in the workplace and gives an indication of how the EAP could most effectively respond to this phenomenon. Mediation as a possible strategy is recommended to deal with workplace romances.

INTRODUCTION

Workplace romances (WRs) are an increasingly widespread phenomenon in work organisations and have become quite common in recent years. This is not surprising, considering the changes that have occurred in the workplace and in society during the past century. People are spending increasingly more time at work, as the trend in today's work-oriented culture is one of longer working days, longer work shifts and higher workloads (Pierce, Aguinis & Adams, 2000:869; Wilson, Filosa & Fennel, 2003:78). Considerably more women are entering the workforce, so there are more mixed-gender teams; the divorce rate is rising and sexual mores are far more relaxed (Lickey, Berry & Whelan Berry, 2009:103). The workplace provides an ideal context for attraction and romance because of the constant proximity of co-workers, the increased time spent together, the sense of "teamwork", and individuals isolated from their (possible) problems at home and with their families. In all likelihood, these conditions will prevail in the future and WR and its impact on organisations will become increasingly more pronounced (Lickey et al., 2009:103).

While, on the one hand, WRs could have beneficial consequences for the individuals involved (such as long-lasting marriages), or even benefits to the organisations, some employers might find them problematic (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:454). WRs, like any other relationships, have the potential to end badly, opening a Pandora's Box of possibly complicated legal, emotional, ethical or productivity consequences.

The question therefore arises whether the employer should have any interest in or concern about the personal relationships of employees with other employees. The answer to this question is aptly summarised as follows by Schaefer and Tudor (2001:1): "Dating a fellow worker is the employee's business until it affects the workplace - when it also becomes the employer's business." In dealing with this matter the following research question is addressed in this paper:

What is the effect of dissolved workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved?

WORKPLACE ROMANCE: THE PHENOMENON

The literature review that follows describes the social phenomenon of dissolved WRs from a theoretical perspective to position the broader debate in this context.

The literature on WR and the categorisation of themes on this topic of study go back to the late 1970s (Cole, 2009:364). Prior to that WR was not often discussed as a separate issue and very little research was conducted on WR and its impact. However, the limited nature of the research did not mean that it was rare or non-existent.

One of the first articles on the topic, in effect an anchor article, was published by Robert E. Quinn (1977). Quinn (1977:30) defined a WR as a "relationship between two members of the same organisation that is perceived by a third party to be characterised by sexual attraction". This definition has been widely cited and used in the literature on WR ever since. Quinn investigated motives, consequences and management interventions relating to this phenomenon. Quinn's seminal work was further developed by Lisa A. Mainiero (1986, 1989). Mainiero published significant research on the motives and consequences of WR, making a unique contribution to this field by developing a theoretical framework of power dynamics in organisational romances (Mainiero, 1986, 1989).

Their lead was followed by various researchers publishing both productively and widely on the topic (Pierce, Byrne & Aguinis, 1996; Pierce, 1998; Pierce, Aguinis & Adams, 2000; Pierce & Aguinis, 2003, 2009; Pierce, Broberg, McClure & Aguinis, 2004; Pierce, Muslin, Dudley & Aguinis, 2008). In 1996 Pierce, Byrne and Aguinis developed a significant model elaborating on the factors influencing the formation and impact of organisational romances. Like Quinn and Mainiero, these later writers also focused on the impact of WR on organisations (Pierce et al., 1996). However, their contribution was unique, as they investigated how the organisation influenced the relationship of the people involved in the WR.

Other researchers in this field built on the above theories and models to explore the phenomenon of WRs in greater depth. The following aspects of WR in particular have received a great deal of attention in the literature on WR.

• Descriptions, models and types of workplace romance

An example of a discussion on these aspects is found in the work by Dillard, Hale and Segrin (1994:242-245, 252), who explored different typologies of WR. According to them, the most common types of WR are (1) a relationship between a male with higher organisational status than his female partner, and (2) passionate and companionate relations, as opposed to "flings or utilitarian relations".

Research into the typologies of WR was continued by Lickey, Berry and Whelan-Berry (2009). They distinguish between three types of WR: (1) employee peer-to-peer (lateral) WR; (2) supervisor and subordinate (hierarchical) WR; and (3) WR when one or both employees are married (Lickey et al., 2009:102). In their typology of WR, each of these relationships can occur as heterosexual or homosexual WRs. Lickey et al. (2009:102) make it clear that, with each type of WR, the potential costs and risks to the organisation increase.

• Antecedent and motivational factors associated with workplace romance

Quinn (1977:44) was the first researcher to inquire specifically about the motivations of WR. He identified three types of motives for entering into a WR: (1) job-related, (2) egotistical, and (3) love. These three motives have been further explored and refined by Dillard (1987:189-192), who explained that, for example, the job motive seeks advancement, security, power, financial rewards, lighter workloads or more time off.

Research by Cole (2009:364), however, emphasises the complexity and diversity of the motivations for the development of a WR. He concludes that the most important motivations are physical attraction, intellectual attraction, shared energy levels, increased self-esteem from success as a team of two, and even the forbidden nature of WR in some workplaces (Cole, 2009:364).

This last notion had already been confirmed by Mano and Gabriel (2006). They investigated not only the motivations for WR on the part of the participants, but also the antecedent circumstances in which it is likely to develop. These two factors should, in Mano and Gabriel's (2006) view, be linked together if the development of WR is to be understood. They conclude that the development of WR depends to a great extent on the "organisational climate", and they found that WRs are more likely to emerge in "hot" climates, where work arrangements foster contact outside work and where organisational policies do not punish those who participate in a WR.

The antecedent conditions (or "organisational climate") are thus also a strong factor which should be kept in mind in trying to understand the reasons for starting a WR. It is thus a combination of personal motivations (job/utilitarian, ego and love) and the antecedent conditions of the organisation ("climate", conservative/liberal, position and gender in the organisation) which all influence the potential development of WRs. As pointed out, it is important to keep this in mind, because to misunderstand the reasons why WR develops in the first place can lead both to co-workers entertaining wrong perceptions of the participants, and to negative effects on the social climate of the organisation, as well as to possibly incorrect managerial intervention.

CONSEQUENCES OF WORKPLACE ROMANCES

A dominant theme in the literature on WR is the focus on the positive and/or negative consequences of the occurrence.

Potential benefits and rewards

Several researchers have investigated the potential benefits and rewards of WR to the organisation in general, to the employees (co-workers) and to the participants in a WR (Cole, 2009; Lickey et al., 2009; Pierce & Aguinis, 2009). It appears that these benefits and rewards are related mostly to the stage when the WR is in full bloom and positive feelings of attraction are in the air. This is in contrast with the stage when the relationship dissolves and the risks are uppermost.

Pierce and Aguinis (2009:455) maintain that, in some cases, organisations may definitely benefit from the performance by employees involved in (intact) WRs. These benefits include increased job satisfaction on the part of the participants in a WR, and increased job involvement and organisational commitment. Pierce (1998) had earlier explained how the rewards of a WR affect not only the participants, but also the organisation according to the "affective spill-over hypothesis". By this he means that a gratifying WR may create an emotional "spill-over effect" in which employees' positive emotional reactions to their romance spill over into their emotional reactions to their job, in the process increasing job satisfaction. With increased job satisfaction comes many more benefits to the organisation, such as positive attitudes, productivity, loyalty and energy (Pierce, 1998:1717).

The rewards and benefits of WRs to the organisation concerned seem to be centred on the notions of increased productivity, loyalty/commitment to the organisation and higher energy levels (Lickey et al., 2009:105). Pierce and Aguinis (2009:455) developed an "impression management hypothesis", according to which these employees try to create a favourable impression by becoming more involved with their jobs and more committed to the organisation.

Cole (2009:364) agrees that a WR can be a very positive force, in that it may increase the motivation and mental energy of the involved parties, so that they work harder and longer. In addition, Cole (2009:364) indicates how a WR can also benefit the co-workers and the organisation in general. He says that WR participants "energise the workplace morale; motivate other employees; encourage creativity and innovation; soften work-related personality conflicts, because the workplace romance participants are happier and easier to get along with; improve teamwork, communication and cooperation; enrich personal relationships for the couple involved and their co-workers; and stabilise the workforce by retaining both partners" (Cole, 2009:364). These are all very important benefits and rewards that any organisation would value and encourage.

The potential benefits and rewards of WR for the organisation, for the participants in WR and for their co-workers are thus diverse, numerous and of great value. It can have an extremely positive effect on the organisation not only in financial terms, but also in terms of creating a positive working environment and climate.

Potential risks and dangers of workplace romance

These benefits and rewards are related mainly to the stage when the WR is in full bloom and there are positive feelings of attraction in the air. There are, however, some obvious risks and dangers associated with WR in its "blooming stage" - risks such as unfairness, favouritism, the formation of groups, jealousy and other such reactions (Powell & Foley, 1998:423). This is the antithesis of the stage of the WR at which the relationship dissolves. It is at this stage of dissolving that the risks of WR predominate.

The potential risks and dangers in WR as far as the organisation, the co-workers and the participants in WR are concerned can be summarised as follows.

• Sexual harassment claims resulting from a dissolved workplace romance

A large body of research on WR focuses on the subject of sexual harassment and how organisations could effectively prevent and manage this in the workplace (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:450-452). They also argue that one of the most common risks of WR from the organisational perspective is that the relationship may disintegrate and could result in claims of sexual harassment, with concomitant lawsuits between the two parties who had formerly been involved with each other.

• Possible retaliation: violence or public confrontation

There is general consensus in the literature on WR that the disruptive dissolution of WRs carries a high potential risk for an organisation, especially if it includes violent behaviour (physical or verbal), especially if this takes place publicly in the workplace. Lickey et al. (2009:105,117) comment in this regard that, in the event of WR dissolution, there are often claims of retaliation by the participants and that this creates a disturbing link with workplace violence. This worsens when one of the parties, or even a third-party stakeholder, feels vindictive or angry. Other researchers observed the prevalence of intimate, retaliating partner violence on work premises, e.g. stalking or physical abuse, which may stem from disruptive dissolutions (O'Leary-Kelly, Lean, Reeves & Randel, 2008:61).

• Staff turnover

The relation between WR and staff turnover is described clearly by Solomon (1998). He warns about the possible expense to the organisation with employee turnover, or the loss of valuable employees who are unhappy working alongside a WR relationship like this, or if employees leave when they opt to continue their relationship at a company that does not prohibit dating (Solomon, 1998:3). Schaefer and Tudor (2001:2) concur, saying that: "productivity is hurt each time a valuable employee leaves a company".

• Legal issues for the organisation

Pierce and Aguinis (2009:454) maintain that unfair management interventions, or even the mere perception that interventions are unfair, pose a major risk in WR. Unfair interventions by management to address WR carry high risks, as Lickey et al. (2009:106) point out. They say that the bottom-line negative consequences of WR to the organisation occur in terms not only of productivity, but also of economic risk and cost. Legal action resulting from a failed WR and consequent management interventions could also include claims of wrongful discharge or invasion of privacy as well as third-party claims of alienation of affection. All these possible legal claims are normally very time-consuming and costly for an organisation. Furthermore, inappropriate sharing of confidential, privileged or proprietary information by parties involved in a WR can result in liability claims from current employees (Lickey et al., 2009:110).

• Unethical relationships

Another risk of WR is that the relationship itself is unethical in the context of the workplace. Pierce and Aguinis (2009:453) say that the most problematic and unethical WRs are extramarital relationships and direct-reporting supervisor-subordinate (hierarchical) relationships. Because social norms generally do not condone extramarital relationships, and because this is aggravated by concerns about lack of professionalism, there are likely to be negative consequences for the company's reputation (Lickey et al., 2009:104).

The risks of unethical hierarchical WRs are described by various researchers (Amaral, 2006; Lickey et al., 2009:103; Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:453; Pierce et al., 2004:69). Cole (2009:364) says that a WR involving people at different hierarchical levels potentially disrupts the organisational power structure and can create high-risk situations and professional conflicts of interest. The author further maintains that a hierarchical WR can affect the co-workers' morale negatively if a subordinate is perceived to be receiving preferential treatment (Cole, 2009:364).

• Emotional disorders and secondary implications

A potential risk in WR that is often not as visible as some of the other risks discussed so far is the risk of emotional disorders experienced after the break-up of a WR. These disorders have a variety of potential "secondary implications" for the organisation. Little (2010) conducted research on this specific risk, focusing on the grief caused by the dissolution of a WR relationship. He concluded that the risk to the organisation is that: "productivity can be lowered when the emotional turmoil following a loss causes an employee to experience difficulties in concentration and judgement, stress, depression, lack of motivation and substance abuse" (Little, 2010:137). These emotional disorders are usually not as visible or easily recognisable as physical ailments and are often misunderstood or left unsupported by management. Such problems also create secondary risks, in that there are financial implications for the organisation, which is now subject to increased health costs, absenteeism, injuries, errors and missed opportunities (Little, 2010:137). Emotional disorders can occur with the dissolution of any romantic relationship, but WR relationships mean that the participants have to work together afterwards (Powell & Foley, 1998:425). Contact often worsens the emotional impact. WR relationships thus carry a very definite risk for the organisation.

• Problems with co-worker relations

The possible risks of WR include the fact that WR could ruin professional relationships, create co-worker confusion and scorn and lead to self-doubt and lost objectivity on the part of the couple, generating competition and conflict (Cole, 2009:364). Lickey et al. (2009:106) emphasise the risk to employees' credibility or integrity if they are involved in a WR.

WORKPLACE ROMANCE, PERFORMANCE AND PRODUCTIVITY

From the organisational perspective, the concern is that a WR may impinge on the participants' performance. The potential link between WRs and productivity has therefore received a great deal of attention in the literature (Lickey et al., 2009:101). Different variables related to WR and performance, such as competence, absenteeism, commitment to the job or intrinsic work motivation and job satisfaction, have been studied. Research distinguishes between intact and dissolved WRs, saying that the two have different associations with productivity.

The question of the link between WR and productivity has given rise to ambiguous views. Quinn (1977:44) found that the job performance by WR participants can either improve or deteriorate. This "mixed result" was repeatedly found over the following four decades, and researchers have produced conflicting results on the topic. For example, Pierce and Aguinis (2009:455) found that the literature and research on the link between WR and productivity delivered mixed results, in that WR could either improve or impair job performance. Furthermore, they found that WR is not necessarily associated with job performance, anyway. It does not necessarily lead to performance impairments, but could instead provide positive associations (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:455). On the positive side, Pierce (1998:1726) and Dillard (1987:190) found that participation in a WR does not inevitably lead to performance impairments but is, in fact, associated positively with job performance.

Pierce and Aguinis (2003), who tested a model of formation and impact factors of WR in organisations, offer an alternative argument, finding that employees' participation in a WR was positively associated with their level of job satisfaction, but not with their level of work motivation or job performance.

This more neutral position was identified earlier by Dillard and Broetzmann (1989), who found that WRs typically have no impact on the participants' job-related behaviours and, if there is a change, it can be explained by the participants' motives for entering into the romance. This is an important factor in the impact of WR and participants' performance at work and the reason or motivation for their WR. Pierce et al. (1996:19) agree with this proposed important link between motive and performance, and state that job performance can be positively affected if the WRs are motivated by love or companionship, as opposed to an egotistical or job-related motive.

In the research on WR the type of the relationship under consideration is also commonly proposed as a variable that affects productivity. Hierarchical as opposed to lateral romances were found to be more likely to decrease productivity (Pierce et al., 1996:19). Although Dillard et al. (1994:253) found that a decline in job performance or workgroup functioning was not associated with hierarchical romances, the opposite view was expressed by Powell and Foley (1998:18). These authors proposed that the two kinds of romance that have the most damaging effects on group morale and organisational effectiveness are hierarchical and utilitarian romances. The latter is described as the type of romance in which one partner satisfies his/her personal or sexual needs in exchange for satisfying the other participant's task-related and/or career-related needs (Powell & Foley, 1998:18). In the researcher's opinion, all of these perspectives emphasise the fact that the type of WR relationship is important in distinguishing it as a potential risk or benefit to the organisation.

Another clear common element in the literature on WR that determines the possibility of WRs being a risk or a benefit is the phase in which the WR happens to be. Pierce et al. (1996:18) perceived that the particular variable, the phase of the relationship, has a definite impact on the level of productivity. They argue that WR participants experience a decrease in productivity, work motivation and job involvement during the early stages of the romance, but an increase of these in the later stages, when the initial excitement has diminished.

It should also be kept in mind when deciding whether a WR is potentially more of a risk than a benefit is to consider its impact on the productivity of the co-workers in the organisation. Schaefer and Tudor (2001:2) maintain that organisational productivity and morale can be negatively affected when WRs are allowed to flourish. They explain that:

"sometimes, an office romance becomes a soap opera played out in front of the entire office", which distracts co-workers and influences their performance negatively.

This argument confirms Quinn's (1977:44) finding that the most common outcome of WRs is that they give rise to copious gossip in the workplace. He says that, unlike non-work-related romances, WRs are subject to the daily scrutiny of co-workers, who question the appropriateness of the relationship, and whether or not the individuals involved or the organisation are benefiting or being hampered by the relationship (Powell & Foley, 1998:4). The lost time and productivity owing to distracted co-workers, who gossip about the WR, are further possible negative consequences for the organisation (Lickey et al., 2009:110). It is thus not only the WR participants' performance that is affected negatively, but potentially also that of all their co-workers. This need not necessarily happen, but it should be recognised as a potential risk.

Whether a risk or benefit to the organisation (especially when it comes to the performance by the WR participants and their co-workers' productivity), it has to be said that this is not a clear-cut issue. However, the important factors listed above should be kept in mind when analysing such a relationship.

The scope of this study does not allow for all the potential risks to be fully explored, but will be confined to disruptive WR dissolutions that could result in retaliation, violence or public confrontations. This includes emotional disorders, with their secondary consequences to the organisation, not forgetting the productivity risks. Other risks are not to be side-lined, and their relevance and importance should be kept in mind throughout this study.

MANAGERIAL INTERVENTION IN WORKPLACE ROMANCE

Management intervention in WRs has recently received considerable attention in the literature, an indication of the growing need and importance of the correct type of intervention by the organisation (Lickey et al., 2009; Pierce & Aguinis, 2009). This includes an exploration of appropriate HR policies on WR.

Research shows that there are essentially two opposing positions on managerial intervention in WR. On the one hand, there is the more authoritarian approach, whereby companies have established strict policies for regulating, prohibiting or punishing WR or even dating (the traditional position is a legal-centric approach to risk prevention) (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:461). On the other hand, there is the more liberal position, which is to allow it by ignoring it totally (Schaefer & Tudor, 2001:2).

A third option is the more current and emerging view, a more casual, "humanistic approach", which assumes that employers cannot regulate employees' love relationships or their personal lives (Schaefer & Tudor, 2001:2). In line with the latter approach, managers could choose to either take no action at all, or take positive action such as engaging in open discussion or counselling. This would make allowances for managing the potential risks and benefits of WR in an organisation. Pierce and Aguinis (2009:457461) chose this option, elaborating on the recommendations for organisations in managing the risks and rewards of WR. They advocate an approach that focuses on cost and benefit management, one with a sensible focus on risk minimisation and reward maximisation.

Within the realm of this third "combined" option, one strategy available to organisations is to offer mediation as an intervention strategy for managing the situation once the WR dissolves and potential risks become apparent. By definition, mediation involves an impartial third party, who mediates with the WR parties to reach mutual agreement on matters of dispute. The underlying principle is that of self-determination and the creation of a future working relationship with the other party (Folberg, Milne & Salem, 2004:262). It is a voluntary option and can occur only if all the parties involved in the dispute are in agreement (Wynn-Evans, 2010:1).

Using an independent third party or mediator can help the parties to work out a solution, thereby avoiding formal grievance and disciplinary procedures (Pearl, 2004:3). As such, it is a potentially empowering option for the individuals involved, as they solve their own conflict instead of having an imposed, adversarial solution (Pearl, 2004:3; Wynn-Evans, 2010:2).

There is general consensus in the literature on workplace mediation that it is an essential tool for managing conflict in the workplace (Armitage, 2009; Carter, 2008; Luna & Yialelis, 2008; Pearl, 2004; Wynn-Evans, 2010). Although mediation has its limitations when it comes to the disputes it can resolve, it is regarded as the most effective when the issues are relationship-based (Carter, 2008:1), for example, WRs. This is particularly true of the EAP, which is relevant in providing a platform offering mediation as a conflict-resolution strategy.

MOTIVATIONS FOR THIS STUDY

There were some serious lacunae in the existing literature on WR, especially in relation to the EAP field, as borne out by the following points.

• Most of the research studies encountered in the preliminary literature review were conducted primarily in the United States of America (USA) and in the United Kingdom (UK). There is thus a need for more contextual research in South Africa.

• The focus of these research studies appears to add value primarily to the fields of human resource management, the legal field (i.e. liability management in cases of sexual harassment) or applied psychology. The research aim was not associated primarily with the EAP field per se, a "gap" that shows clearly in the assessment of the literature.

• The aim of this research was not on unschooled (or semi-schooled) workers. The question (or "gap") of the applicability of the findings on professional employees' WRs and WRs in the context of a factory set-up is apparent.

• Another problem with the existing literature on WRs is the fact that the current research focuses on WRs in general, not on the "break-up phase" of the WR. The consequence of this is that, firstly, the real effect of dissolved romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved is not sufficiently defined and understood. Secondly, the negative effects of dissolved WRs might be underestimated. Thirdly, the EAP guidelines are too general for dealing with this situation and are therefore eventually experienced as inadequate.

• The relation between WR and performance/productivity is one of the main themes in the literature on WR (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:455), which also relates to the topic of this research study. Considering the mixed results that past research has delivered in this respect (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:455), it should be of great value to investigate what the result would be at the specific organisation where the research for this study was conducted. This would be potentially valuable to the management of the organisation, not only in calculating their potential losses, but also in motivating the prospects of a well-established managerial intervention strategy for WR.

It can be concluded, therefore that, although there is substantial existing research on WRs in the EAP field, further and more up-to-date research is required if it is to be applicable in the South African context, hence this contribution.

Another motivation for this study was to answer the need to further develop Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs) to deal with WRs. Normally, referrals to the EAP of employees involved in romantic relationships at work are made by the team leaders at the point when the relationship breaks down, in the hope that the associated conflict and tension causing productivity problems will be addressed. There is thus a need for a timely and effective strategy for the EAP practitioner to respond to these situations, so that the affected employees can return to full productivity as soon as possible. By conducting research on these aspects of employees' wellbeing and on the impact on the organisation's productivity, this study endeavours to contribute to organisational development. In other words, insight into the effects of dissolved romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved would empower an organisation (management, supervisors, team leaders and EAP practitioners) to address the phenomenon of WRs more effectively.

In addition, the principal researcher has been professionally involved in EAPs since 2008, and has observed how many dissolved workplace romances have had a disruptive effect on the workplace. Her interest in gaining a deeper understanding of the concept and implications of WRs and how the EAP could add value to this field acted as a motivation for undertaking this study

RESEARCH GOAL AND OBJECTIVES

Against the background of the above literature review describing the phenomenon of dissolved workplace romances, the following research goal was formulated for this study:

To develop an in depth understanding of the effect of dissolved workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved.

In order to achieve the research goal, the following objectives were set:

• To obtain a sample of employees who were involved in a workplace romantic relationship, which ended;

• To conduct semi-structured interviews with them aided by open-ended questions contained in an interview-guide about the effect of their dissolved workplace romances on their psychosocial functioning and productivity;

• To explore the effect of dissolved workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved;

• To sift, sort and analyse the data obtained according to themes;

• To describe the effect of dissolved workplace romances on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved;

• To interpret the data and conduct a literature control in order to verify the data;

• To draw conclusions and make recommendations about strategies for an EAP in dealing with the effects of dissolved WRs at an industrial clothing factory in Cape Town.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was followed which focused on gathering meaningful information about employees' perceptions, experiences and feelings in relation to the phenomenon of relationship breakdown in the workplace and its effect on their productivity.

This study was conducted in an industrial setting, a clothing factory in Cape Town, with approximately 1 600 production workers. The employees who formed the focus of the research are in the lower-income bracket and have low levels of formal education. The cultural composition is approximately 75% Afrikaans-speaking Coloureds, and 25% Xhosa-speaking Africans (most of the Africans are able to understand Afrikaans). The population is predominantly female, with approximately 200 male employees, ensuring a regular occurrence of romantic interaction in the workplace.

Interviews were conducted with a sample of 11 individuals of the wider population in the closed EAP caseload who were selected to participate in the study. Data saturation was taken into consideration in the process of interviewing participants. The selection was carried out by the non-probability sampling method of purposive sampling. This was regarded as the most appropriate method for this study, where many members of a small subset of a larger population are easily identifiable, but it would be impossible to enumerate those who are relevant in this research context (Babbie & Mouton, 2001:166).

The criteria for inclusion were that:

• the participants had to still be employed by the company;

• they must have been involved in a workplace romantic relationship, which ended;

• the relationship should be regarded as a serious long-term one as opposed to a short-term affair - for example, either include the couple being married, having had co-habituated or having a child together;

• the relationship should have been "lateral", that is the couple must have been working on more or less the same level of authority; and

• participants must not have been involved in counselling at the moment of data collection (if applicable, services had to be formally terminated before the data collection).

Data were collected by means of a semi-structured interviewing method (by means of an interview guide with some predetermined questions). The questions were open-ended and allowed room for initiative by the interviewer to explore additional information that the participant has raised (Alston & Bowles, 1998:116). The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed afterwards. Copies of the transcripts were given to the participants before the data were analysed and integrated into the findings to allow for the participants to approve of the content and confirm that they were correctly quoted and understood.

The interviews were not conducted by the researcher herself but by a suitably qualified person (registered social worker, bound by the standard code of ethics and regulations around confidentiality) contracted solely for this purpose. The advantage of this arrangement was that enhanced objectivity was ensured by the interviewer, which contributed to the trustworthiness of data collected.

The research findings that resulted from the process of data collection and analysis are outlined below.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Profile of participants and their relationships

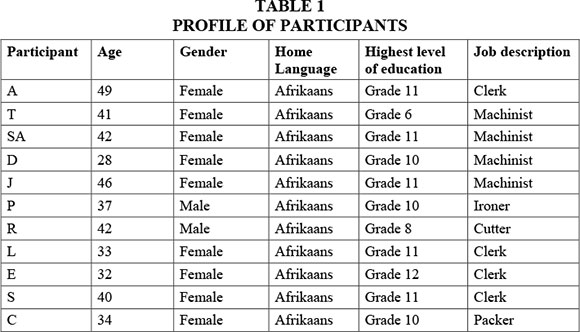

The majority (9 of out 11) of participants were female and between the age of 28 and 49. Participants' job titles varied between clerk, machinist, ironer, cutter and packer. Their mother tongue was Afrikaans and their education levels varied between Grade 6 and Grade 11 (refer Table 1).

The length or duration of the romantic workplace relationships varied. The shortest relationship was at least six months (one participant), and the longest relationship was 15 years (two participants). Six participants were married to their partner and eight of the participants had one child or more with their partner (in question). Nine out of the 11 participants co-habited at some point in the relationship, ranging in duration between a minimum four months and maximum 15 years. The 11 participants included two ex-couples, meaning four of them were involved with each other and the rest were involved with other employees outside the sampling group.

It may be deduced from the information above that the participants' relationship profile therefore fitted the criterion of being in a serious long-term relationship rather than in a short-term affair.

All the participants were on approximately the same work level as their ex-partners, in the sense that none of them was in a superior position, with the other reporting directly to him/her, which accords with the participation criteria.

Ten of the participants responded that they perceived the break-up as being inimical, with only one participant saying it had been amicable.

Furthermore, of the total of nine relationships, six had broken up because of a third female party, who was also a work colleague. Most of the male parties in the relationships actually proceeded to enter into another workplace relationship after the break-up (this needs to be viewed in the context where the workforce of 1 600 consists mainly of females with only about 200 males).

Presentation of the themes and literature control

An elaboration of the themes that emerged during the study follows below.

Psycho-social functioning

The theme of the effects of dissolved WRs on the psychosocial functioning of the employees involved and their co-workers was explored in the interviews with participants. Emotional problems, such as concentration difficulties, stress and depression, lack of motivation and increased substance abuse, can occur with the dissolution of any romantic relationship. However, as indicated in the literature review, it is different for WR break-ups, in that the participants have to work together after the romance is over. This continued contact often worsens the emotional impact. Emotional disorders are usually not as visible as physical ailments and could create secondary risks for the organisation, such as increased absenteeism, mistakes or increased health costs.

In this regard participants reported a decrease in their concentration levels, as their attention was more focused on the relationship instead of on their work; they felt easily distracted and struggled to concentrate on their work. Five participants answered that they experienced difficulty with decision-making.

For example, J reported:

I could not make decisions at work. I remember one incident when I became sick at work because I was too emotional and had to be sent home. ("Ek kon nie besluite maak by die werk nie. Ek kan onthou een 'incident' by die werk, wat ek siek geraak het by die werk en net begin te 'emotional' raak het, dat hulle my moes huis toe gestuur het" [sic])

SA: I could not concentrate on my work. My supervisor recognised this. ("My konsentrasie was nie by my werk nie. Die supervisor het opgelet... ")

On the other hand, three participants reported that there had been no impact on their concentration levels or decision-making abilities, while two others felt relieved that they could keep busy at work in order to escape from their preoccupation with their feelings about the break-up.

In terms of the negative experience of stress, the research indicated that most participants reported increased levels of stress during the break-up. The "stress" related to different factors, i.e. adjustment, coping with gossip, raised anxiety levels and having to face their ex-partner every day at work. It is significant that the majority of the participants felt so stressed that they considered resigning from their jobs.

Also, when it came to sadness, seven participants answered affirmatively to the question as to whether they experienced this feeling during and after the break-up. Seven participants indicated that, for them, the experience was so intense that it bordered on depression, in that some lost interest in their personal hygiene and appearance. Others experienced decreased energy levels or had trouble sleeping.

For example: J reported:

I was very depressed. It felt as if nobody cared about me and that happiness was not meant for me. That I was meant to be alone. I cried bitterly. ("Ek was baie depressed. Dit het vir my gevoel laat niemand vir my omgee nie. Dat geluk nie vir my beskore is nie ... om alleen te wees ... Ek het verskriklik baie gehuil. ")

A significant trend, therefore, is the experience of sadness and depression experienced by participants during the break-up, which was reflected in a severely negative impact on their psychosocial functioning.

The same can be said of substance-use during the break-up. Eight participants responded that they had increased their use of substances, which confirms the negative impact of the dissolution of the WR on their psychosocial functioning.

For example, L says that, although she used to drink over weekends, she suddenly started to drink during the week as well, as she could not care less about her situation:

I stopped worrying about what others at work thought of me, they could say what they liked about me at work. ("Ek het net gedink... ek worry nie, hulle kan maar sê wat hulle wil by die werk".)

Regarding levels of self-confidence, the research reflects the fact that, during and immediately after the break-up, the participants experienced a blow to their self-confidence. However, looking at the impact over the longer term, 6 participants reported feeling relieved that the relationship was over (particularly if it had been unhappy), with increased levels of confidence in general.

This finding is demonstrated well by participant L:

I felt very insecure about myself and wondered what was wrong with me. He really crushed my self-esteem. But when we broke up, my life began. (" Ek het baie onseker van myself gevoel. En dink ek: Wat is dan fout met my? Hy het regtig my selfvertroue geknak, regtig waar... (maar) toe ons nou opbreek, toe het ek 'n lewe".)

It can therefore be deduced that WR dissolutions can impact negatively on participants' levels of self-esteem in the beginning stages, when emotions run high, but the longer-term impact on psychosocial functioning actually looks positive.

The researcher deliberately asked the question "What was the most difficult experience during the break-up?" to probe whether or not the break-up had been particularly challenging because of its public nature in the workplace. Some participants answered affirmatively, indicating that it had been particularly hard to see each other every day. Five participants answered that the most difficult experience was the negative effect on the children, as demonstrated, for example, by:

P: I was sad for my child because now he would grow up without his father.

("Hartseer vir my kind. My kind, omrede... Nou gaan hy ook groot word sonder sy pa".)

R: The hardest part was that now I will see my daughter much less often than I would like. ("Moeilikste deel is... ek gaan my dogtertjie baie minder sien as wat ek graag wil sien ".)

Another main trend emerged as the majority of the participants' relationships (six out of the nine sampled) had, in fact, broken up because of the intrusion of a third (female) party, also a work colleague, on site. This had complicated the break-ups to the extent that the participants experienced double the exposure and humiliation, because not only the break-up, but also the establishment of a new WR for the male party occurred in the public domain.

For example, D said:

He had another girl at work, and everybody was talking about it because he had made her pregnant. ("Toe is die nou, dat hy iemand by die werk het ... en almal praat daarvan ... want hy het vir haar swanger gemaak".)

This is significant in the sense that it possibly indicates that the particular work environment of the clothing factory in question is a "hot" environment: it seems to foster the development of romantic relationships at work. Furthermore, most of the employees reside in the same residential communities and often socialise at home.

This finding reflects the theory of Mano and Gabriel (2006), who found that the development of WRs depends a lot on the "organisational climate", and that WRs are more likely to emerge in "hot" climates, where work arrangements foster contact outside work and where organisational policies do not punish participants in WR (which is also relevant to this specific environment).

Proposing the existence of a "hot climate" in this instance makes further sense, considering the demographic composition of the employees. The majority (1 400) of the 1 600 employees are female, and the majority of them are single or divorced. It would appear, therefore, that for male employees there are ample opportunities for multiple WRs simply by virtue of the sheer availability of females.

A conclusion on the first group of questions concerning the theme "Psychosocial functioning" is neither clear-cut nor consistent. Different participants had different and unique emotional experiences, and the impact on their functioning varied from time to time and from individual to individual.

However, on the whole, and looking at the responses concerning this theme in general, the findings of the literature review are confirmed, in that the general psychological and emotional functioning of individuals involved in WRs is negatively affected. In general, the break-ups resulted in decreased concentration levels and decreased decision-making abilities, increased stress, sadness and depression levels, and an increased use of substances, as well as, at least immediately after the break-up, decreased self-confidence levels.

Social functioning

In this research study the matter of risks of a social nature was investigated under the theme of social functioning, with indicators of social coping, withdrawal behaviour, the experience of office gossip, conflict with colleagues, and communication with colleagues.

Looking at the various responses to the question of how the participants coped socially during and after the break-up, it appears that most of them had some difficulty with this. A sense of isolation and decreased levels of socialising emerged and was a general experience among the participants.

A clear trend emerged from the participants' responses to the question: "Did you feel like withdrawing from your colleagues at work?" Five participants answered affirmatively to this, reporting that they had had to take a few days or up to a week off from work in order to withdraw from that environment. They also reported withdrawal behaviour at work, for example, avoiding colleagues during breaks.

SA: Everyday during lunch times and tea times, I went outside, and then I would come in. I was on my own. (" Lunch time, tea time, was ek maar net daar buite en dan kom ek maar weer in. Elke dag so. Op my eie was ek".)

Office gossip was a common experience for the participants. Two of them reported that they were unaffected by the gossip, while the rest (9), experienced it rather negatively. It created a sense of humiliation, sadness, tension or lack of comfort in the working atmosphere. The participants' perceptions of the workplace were therefore negatively affected by their experience of the gossip, to the extent that they developed a resistance to going to work and needed to withdraw, as described above.

Participant P said: It upset me terribly and made me felt uncomfortable. I felt I did not want to work here any more. ("Dit het my baie, verskriklik baie ontstel, ongemaklik laat voel. Dit het gevoel ek wil nie meer hier werk nie".)

T felt uncomfortable because: Everyone was talking. They were saying I was mad, crazy. ("...die mense het gepraat. Hulle het gesê ek is mal, ek is siek in my kop".)

Another trend in the participants' experience was that of increased levels of conflict with their work colleagues. Feelings such as irritability, anger, impatience, quarrelsomeness, rudeness and unfriendliness were reported. All of these feelings are conflict-related and had, or were likely to have, a negative impact on their level of social functioning at work.

In summary, appreciating the different and often conflicting experiences by participants regarding the theme of social functioning, it can be inferred that the break-up of a WR generally had a negative effect. The participants' social coping skills were affected in some way or another, and most of them experienced withdrawal. Office gossip was an enormous issue for them, and increased conflict with work colleagues was reported.

Retaliatory violence

With reference to the theme of retaliatory violence, there is consensus in the literature that disruptive dissolutions of WR have a potentially high risk for an organisation in the sense that the dissolution could result in retaliatory violence on the work premises, affecting the participants' and their co-workers' job performances (Lickey et al., 2009:105,117). This may get worse when one of the parties feels vindictive, angry or resentful.

This research investigated the occurrence of retaliatory violence and the associated negative feelings under the indicators of violent threats, acts or incidents; effects of violent threats or acts; negative emotional experience (fear or intimidation); and experiencing feelings like anger or resentment.

The occurrence of violent threats, acts or incidents at work following the break-ups was a definitive theme. Four female participants shared that they approached their ex-partners at work in an intimidating or verbally violent manner.

L: I was the one who approached him to tell him off. When we broke up, I went up to him to swear and shout at him, everyday. Once, I took his phone and wanted to break it, but my friends stopped me. ("Ek was die een... dan het ek vir hom gaan insê (slegsê)... Toe ons opbreuk... dan het ekhom uitgeskel en gevloek ...Geskel, elke dag ... dan skel ek hom uit en ek het een keer sy 'phone' afgevat. Ek wou dit stukkend gooi, maar toe keer my vrinne my ".)

One said that she physically hit her ex-partner at his machine.

J: Yes, I did slap him once, at the machine. Because ... he was being irritating.

("Ja daar was een keer wat ek hom geklap het, by die masjien. Want... hy was krapperig gewees ".)

Another incident was more serious, when a woman was physically and verbally assaulted by her ex-partner at her work desk.

The participants who had been on the receiving end of such violent threats or acts responded that they usually reacted by avoiding or walking away from their ex-partner. Some (2) felt embarrassed about it, some (2) felt uncomfortable, but the majority (7) struggled with feelings of anger and resentment against their ex-partners.

T: I would get angry for no reason, with my supervisor as well. (" Ek het lelik kwaadgeraak... Ek was sommer net kwaad, sommer vir my supervisor ook".)

D: When somebody asked me something, I would bite their head off for no reason because I was irritable and misinterpreted everything. ("Nou as hulle miskien net iets vir my kom vra ... dan byt ek sommer hulle kop af of so. Vat dit mos nou verkeerd op".)

These negative emotional experiences sometimes resulted in malicious intent towards those around them; for example, participants experienced increased levels of irritability with their colleagues or supervisors. Financial disagreements between ex-partners in particular were one of the primary reasons for this negativity.

In summary: the study indicates that the occurrence of retaliatory violence, with the associated negative feelings of anger, resentment and fear, was commonplace. This confirms the suggestion in the literature review that retaliatory violence counts as a major potential risk to the organisation when WRs dissolve.

This finding is significant and points out the irony that the organisation prohibits family members or partners of employees from entering the grounds because it has been identified as a safety risk. However, there are no policies or measures in place that consider the risks of employee family members or partners who are working together and who pose a similar potential risk to each other's safety.

Productivity implications

With reference to the theme of the productivity of the employees involved and their co-workers in the industrial clothing factory in Cape Town, the study indicated mixed results regarding participants' responses as to whether or not the break-up had any impact on their usual level of work functioning. Half of the participants answered that it had had a negative impact, while the other half answered that it had had no impact whatsoever. One answered that she actually worked harder to compensate for the lack of trust her colleagues had in her.

With regard to the question of how the break-ups affected their attendance, all the participants shared that their attendance had been negatively affected, ranging from being absent for a few days up to a week or more. They usually listed it as "sick leave" and said they took the leave either because of their need to withdraw temporarily from the workplace, or to attend court cases resulting from the break-up.

D: I was frequently absent, I just felt anxious with lots of things running through my mind. Then I just needed to take time off work and be alone at home. ("... ek was baie afwesig... jy voel nou net gespanne en goed gaan deur jou 'mind'. En dan moet jy net afvat en alleen wees by die huis ".)

The last productivity indictor to be investigated was the way in which the participants perceived the level of motivation and commitment to their work. A main theme was the negative impact of the experience, and they gave examples of how hard it had been for them to continue as normal during that time.

D: I did not do my work as I usually did. I just did not want to be there. I could not put in my usual effort and my work wasn't up to scratch. ("Ek het nie my werk gedoen soos ek dit moet doen nie. Daar was net nie ... ek wou net nie hier gewees het nie ... Gee nie 'capacity' wat ek moet nie. My werk was nie dieselfde gewees nie".)

Having children to look after was the main reason why participants were motivated to carry on doing their work.

J: Even though I didn't want to go to work, I had no choice because of our child.

("Ek het gevoel ek wil nie werk nie, maar ek het nie 'n keuse gehad nie. Weens ons kind".)

In summary: the research suggests the theme that productivity indicators such as the level of functioning at work, attendance and the level of work motivation and commitment generally suffered. It is clear that WR break-ups do potentially have a negative effect on productivity.

Necessity and best strategies for an EAP

The theme of participants' perceptions about the necessity and best strategies for an EAP in dealing with the effects of dissolved WRs were also explored. In view of the described risks to the individuals involved, as well as to the organisation as a whole, it is imperative for the company to respond proactively to avoid further escalation and further costs. Besides the more formal company involvement and measures such as a disciplinary recourse, the company could also respond by following the counselling policy that was already in place by offering the EAP service to all the employees.

The study indicates that nine of the participants made use of the EAP service during or after the break-up, most of them self-referred. Their feedback on whether or not their expectations were met by the service was mainly positive, confirming that the EAP gave them the opportunity of talking about their WR, which helped them come to terms with the situation.

S: She listened and that was the most important thing. ("... sy hetgeluister en dit was die belangrikste".)

Looking at their responses under the heading "Communication" in the study, 10 participants reported that communicating openly with their work colleagues, if only just a few trusted friends, their supervisor or the EAP social worker, was experienced as helpful.

Seven participants were unaware of any company policies prohibiting WR, and they felt that, even if they had been aware, it would not have been a deterrent. Therefore, they did not think this would have been an effective management intervention.

L: I don't think there should be such a rule because you can't just stop your feelings for someone. (" Ek dink nie daar moet so ' n reël wees nie, want niemand kan sulke gevoelens vir mekaar keer nie".)

One participant suggested that there should be a policy prohibiting extramarital affairs, which makes sense in view of the literature review (Pierce & Aguinis, 2009:453), where it is suggested that these relationships are regarded as unethical and could pose a potential risk to the company.

Asking participants to suggest ways of improving the existing EAP to better respond to similar predicaments in future, a common majority point was that the EAP should counsel the parties together to defuse the conflict, to talk about what had happened, to help implement boundaries and to mediate differences peacefully.

The participants who underwent mediating interventions by the EAP gave positive feedback on this and suggested that this should be repeated in similar situations.

For example, P suggested that if couples are seen together:

The couple should be called in together to talk to the social worker about their relationship. It's good to have someone like a social worker at work because there are a lot of troublesome things at home and some of us can't afford to go to someone outside work. This gives one motivation to come to work. ("... hulle word saam ingeroep en praat oor die huwelik ... want kyk, om iemand te hê, soos die maatskaplike werker by die werksplek, is baie goed. Want daar is baie dinge by die huis en sommige van ons kan dit nie 'afford' om na iemand buite te gaan nie, want ons het nie daai geld nie. Om iemand soos dit by die werk te hê, gee vir jou die motivation om te kom werk".)

T: She could be helpful because you can be rude to each other when you are in a relationship, she could help you to keep the relationship on the straight and narrow. ("Sy kan vir hulle almal help ... 'n mens is onbeskof met mekaar wanneer jy in 'n verhouding is ... sy kan help om die verhouding so 'n bietjie op die pad te hou".)

In summary, it appears that the EAP was seen as a helpful opportunity for affected employees to receive counselling support in coming to terms with a break-up. The chance to talk about their feelings in a professional and confidential environment was experienced positively. Furthermore, it was clearly suggested by seven of the participants that the EAP could be even more effective if the two parties were seen together by the counsellor in a constructive set-up to address the various issues that emerged during the break-up.

Suggestions for further research

The following suggestions are made for further and future research on the effect of workplace romances on employees and the organisation in general and more specifically on the psychosocial functioning and productivity employees.

• Given the limitations of this study, it would be of academic value to reflect on the outcome of a research study focusing on the comparison of participants' supervisors and colleagues' responses to the same indicators.

• A mixed-method research strategy should be applied to incorporate qualitative findings on the participants' production statistics for a more objective angle of comparison. These steps would possibly produce even richer information as they may bring about greater neutrality and objectivity, as opposed to the subjective approach of this study.

• Relevant closed EAP case files could be analysed to carry out a record analysis of the interventions provided and to decide whether or not they had defused the work conflict. This might shed more light on possible EAP intervention strategies to deal with similar situations in future.

• The effect of disruptive dissolution of a WR, which has the particular potential for retaliation and violence, not forgetting the emotional disorders and secondary risks to the organisation, must be investigated further. Supplementary research is required regarding the disturbing outcome of this research about the high occurrence of retaliatory violence on work premises and the resulting costs to the company, which has to resort to disciplinary action by applying the workplace violence policy. The company could, for instance, explore the number of disciplinary hearings owing to workplace violence, linking them with retaliatory violence due to WR break-ups. The company could possibly acknowledge the importance of identifying high-risk individuals early on and refer them to the EAP for mediation. Certain interpersonal boundaries could be implemented to prevent any future occurrence of workplace violence.

• Further research could be conducted on the potential value of mediation interventions as part of the EAP to defuse and manage situations of interpersonal conflict in the workplace (such as those caused by WRs that have broken down).

CONCLUSION

This study confirms the overall negative effect of the breakdown of WRs on the psychosocial functioning and productivity of the employees involved in the workplace. Furthermore, it gives direction on how the EAP could best respond to this type of interpersonal conflict situation in the workplace, i.e. by means of mediation. The researcher's view is that mediation should be recognised and regarded as a primary means of intervention by a company's EAP to respond to WRs that dissolve in order to proactively protect the individuals involved as well as the company at large from the possible escalation of negative outcomes.

In view of the insights obtained, the envisaged significance and contribution of this research is its focus on a very specific South African context: an industrial clothing factory in Cape Town during the years 2012-2013. This narrowly-defined context, which incorporates the context of South African and "un- or semi-schooled" employees, will go towards making this research contextual, relevant, manageable, focused and significant by addressing the gap in information on this topic, thereby creating new, relevant knowledge

REFERENCES

ALSTON, M. & BOWLES, W. 1998. Research for social workers: an introduction to methods (2nd ed). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

AMARAL, H.P. 2006. Workplace romance and fraternization policies. University of Rhode Island: Schmidt Labor Research Center. [ Links ]

ARMITAGE, C. 2009. Mediation is good for everyone. New Zealand Management, 57:7. [ Links ]

BABBIE, E. & MOUTON, J. 2001. The practice of social research (South African ed). Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CARTER, C. 2008. Limited future for workplace mediation. Personnel Today, 11:9. [ Links ]

COLE, N. 2009. Workplace romance: a justice analysis. Journal of Business Psychology, 24:363-372. [ Links ]

DILLARD, J.P. 1987. Close relationships at work: perceptions of the motives and performance of relational participants. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4(2):179-193. [ Links ]

DILLARD, J.P. & BROETZMANN, S.M. 1989. Romantic relationships at work: perceived changes in job-related behaviors as a function of participant's motive, partner's motive, and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19:93-110. [ Links ]

DILLARD, J.P., HALE, J.L. & SEGRIN, C. 1994. Close relationships in task environments: Perceptions of relational types, illicitness, and power. Management Communication Quarterly, 7:227-255. [ Links ]

FOLBERG, J., MILNE, A.L. & SALEM, P. 2004. Divorce and family mediation models, techniques and applications. New York: The Guildford Press. [ Links ]

LICKEY, N.C., BERRY, G.R. & WHELAN-BERRY, K.S. 2009. Responding to workplace romance: a proactive and pragmatic approach. The Journal of Business Inquiry, 8(1):100-119. [ Links ]

LITTLE, S. 2010. Workplace responses to employee grief following the dissolution of a romantic relationship. Conference report to the 2010 Academy of Management Conference, University of Montana, Missoula. [ Links ]

LUNA, C. & YIALELIS, L. 2008. Mediation solves problems with help of those involved. The Wenatchee Business Journal, 2:39. [ Links ]

MAINIERO, L.A. 1986. A review and analysis of power dynamics in organizational romances. Academy of Management Review, 11(4):750-762. [ Links ]

MAINIERO, L.A. 1989. Office romance: love, power, and sex in the workplace. New York: Rawson Associates. [ Links ]

MANO, R. & GABRIEL, Y. 2006. Workplace romances in cold and hot organizational climates: the experience of Israel and Taiwan. Human Relations, 59(1):7-35. [ Links ]

O'LEARY-KELLY, A.M., LEAN, E., REEVES, C. & RANDEL, J. 2008. Coming into the light: intimate partner violence and its effects at work. Academy of Management Perspectives, 22(2):57-72. [ Links ]

PEARL, J. 2004. Worth fighting for. Community Care, 1535. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A., BYRNE, D. & AGUINIS, H. 1996. Attraction in organizations: a model of workplace romance. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 17(1):5-32. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A. 1998. Factors associated with participating in a romantic relationship in a work environment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(18):1712-1730. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A., AGUINIS, H. & ADAMS, S.K. R. 2000. Effects of a dissolved workplace romance and rater characteristics on responses to a sexual harassment accusation. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5):869-880. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A. & AGUINIS, H. 2003. Romantic relationships in organizations: a test of a model of formation and impact factors. Management Research, 1(2): 161-169. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A., BROBERG, B.J., McCLURE, J.R. & AGUINIS, H. 2004. Responding to sexual harassment complaints: effects of a dissolved workplace romance on decision-making standards. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(1):66-82. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A. & AGUINIS, H. 2009. Moving beyond a legal-centric approach to managing workplace romances: organizationally sensible recommendations for HR leaders. Human Resource Management, 48(3):447-464. [ Links ]

PIERCE, C.A., MUSLIN, I.S., DUDLEY, C.M. & AGUINIS, H. 2008. From charm to harm: a content- analytic review of sexual harassment court cases involving workplace romance. Management Research, 6(1):27-46. [ Links ]

POWELL, G.N. & FOLEY, S. 1998. Something to talk about: romantic relationships in organisational settings. Journal of Management, 24(3):421-448. [ Links ]

QUINN, R.E. 1977. Coping with Cupid: the formation, impact, and management of romantic relationships in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(1):30-45. [ Links ]

SCHAEFER, C.M. & TUDOR, T.R. 2001. Managing workplace romances. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 66(3). [ Links ]

SOLOMON, C.M. 1998. The secret's out: how to handle the truth of workplace romance. Workforce, 27(7):44-48. [ Links ]

WILSON, R.J., FILOSA, C. & FENNEL, A. 2003. Romantic relationships at work: does privacy trump the dating police? Defense Counsel Journal, 70(1):78- 88. [ Links ]

WYNN-EVANS, C. 2010. Sweet harmony. Employers Law, 9. [ Links ]