Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.51 n.2 Stellenbosch 2015

http://dx.doi.org/51-1-444

ARTICLES

Reflective supervision: Guidelines for promoting resilience amongst designated social workers

Elmien TruterI; Ansie FouchéII

ISocial Work Division, Faculty of the Humanities North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus, Vanderbijlpark, Gauteng, South Africa. <Elmien.Truter@nwu.ac.za>

IISocial Work Division, Faculty of the Humanities North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus, Vanderbijlpark, Gauteng, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The importance of child protection as well as the designated social workers (DSWs) assigned to them, and the jeopardy they face, is well recognised. Although there is a call to enhance DSW resilience, little is known about their resilience, and there are no guidelines to equip South African DSW supervisors to promote supervisee resilience. This article proposes resilience-enhancing guidelines for South African DSWs within reflective supervision. These suggested guidelines are based on empirical research findings pertaining to (a) a systematic meta-synthesis of DSW risk and resilience; (b) indicators of South African DSW resilience; and (c) the lived experiences of 15 resilient South African DSWs.

INTRODUCTION

In South Africa a specific group of social workers assigned to protect vulnerable children are referred to in the Children's Act, Act 38 of 2005 (Bosman-Sadie & Corrie, 2010:7) as "designated social workers" (DSWs). They are also known worldwide as, amongst other terms, child protection social workers (CPSWs) statutory social workers, front-line workers, child welfare workers, and children's services [workers] (Conrad & Kellar-Guenther, 2006; Douglas, 2013; Jones, 2001; Kearns & McArdle, 2012; Law, 2011; Littlechild, 2003; Narain, 2011; Russ, Lonne & Darlington, 2009). For the purposes of this article, they will be referred to either as DSWs or CPSWs.

Globally CPSWs protect vulnerable children by means of statutory services, and as a result of the taxing and physically dangerous context of the CPSW setting, they are placed at risk of negative outcomes, which in turn has detrimental consequences for their and their client's wellbeing (Gibbs, 2001). CPSWs who adapt positively to the adversities they face could be regarded as resilient (Adamson, 2012; Masten, 2011). As such, there is evidence in the literature of some CPSWs who demonstrate resilience despite the risks of the profession (Kearns & McArdle, 2012; Hurley, Martin & Hallberg, 2013; Truter, 2014). Much could be learned from these CPSWs who adapt positively in situations that others might find intolerably stressful, and these lessons could ultimately suggest directions for enhancing resilience in others (Russ et al., 2009). One vehicle to enhance resilience in CPSWs is professional supervision (Adamson,2012).

Several authors argue for a reflective approach in supervision, where the focus of the attention is not only on the task but also on the emotions and experiences of the CPSW (Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Franklin, 2011; Russ et al., 2009). Reflective supervision thus creates a context in which the facilitation enables a person to think and talk about a distressing experience or event, to analyse such an event, and to ascribe meaning to it (Franklin, 2011). Goddard and Hunt (2011) and Russ et al. (2009) maintain that resilience enhancing for CPSWs is well suited to the context of reflective supervision, because it provides an opportunity for positive appraisal of challenging situations and further provides a setting for reflecting on and managing emotional responses. Conversely, it is reported in the literature that current supervision practices in CPSW are inadequate and are mostly focused on the administrative aspects of the job rather than the emotional needs of the CPSW; therefore alternative approaches such as reflective supervision directed towards positive outcomes, such as resilience, are recommended (Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Goddard & Hunt, 2011). Reflective supervision might ultimately nurture CPSW resilience in order to benefit CPSWs, the children they seek to protect as well as communities at large.

Attention was recently drawn to the way that reflective supervision in social work might enhance resilience in social workers in South Africa (Engelbrecht, 2013). In addition, informal feedback from South African social work supervisors confirmed their own need not only for knowledge, but also for practical guidelines on how to assist the promotion of resilience in the DSWs under their supervision. So far, however, there has been little discussion in the literature on resilience-enhancing guidelines within reflective supervision practices in South Africa; the purpose of this study is therefore to explore this phenomenon by proposing possible related guidelines in line with earlier empirical research findings on the resilience of South African DSW (Truter, 2014; Truter, Theron & Fouché, 2014).

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Risk and resilience in designated social workers

It is indisputable that all social workers, whatever their field of specialisation, are placed at risk by challenges such as work overload, staff shortages and secondary traumatic stress (Gibbs, 2001; Kim, Ji & Kao, 2011; Littlechild, 2003; Morris, 2005; Stanley, Manthorpe & White, 2006; Storey & Billingham, 2001; Tham, 2006; Yürür & Sarikaya, 2012). However, a recent systematic meta-synthesis (Truter, 2014) highlights the particularly taxing and physically dangerous context of CPSW such as exposure to violence and aggression, and the very taxing nature of protecting abused or vulnerable children, and making very difficult decisions about their safety (Sayers, 1991; Munro, 1996; Gibbs, 2001). The likely negative outcomes for CPSWs when exposed to these risks are highlighted in the literature as burnout, high attrition rates, compassion fatigue and depression (Beckett, 2007; Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Collins, 2008; Russ et al., 2009; Truter, 2014). However, when people adjust well to risk, resilience processes - typically supported by constructive social ecologies - might explain their positive adaptation (Ungar, 2011).

Resilience in this context is a complex interaction between a person at risk and a given social ecology that engages in resilience-supporting processes which encourage functional outcomes in the face of challenging circumstances (Ungar, 2011, 2013). Given the attention drawn to CPSWs' particularly taxing work contexts, as well as the mandatory role they play in the protection of vulnerable children, it became imperative for us to better understand the resilience of CPSWs and more specifically South African DSWs (Carson, King & Papatraianou, 2011). Enhancing resilience in CPSWs has not been given much attention in relevant literature (Truter, 2014), and in South Africa resilience-enhancement guidelines for professionals at risk have been investigated only in professions such as teaching and nursing (Koen, 2010; Wood, Ntaote & Theron, 2012). The findings from two recent studies suggest that the social ecology of South African DSWs would typically include family, friends, colleagues and supervisors (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014). Since the CPSW supervisor represents one facet of a CPSWs' social ecology, we advocate for CPSW supervision to be considered an ideal platform where CPSW resilience might be promoted.

Supervision

The importance and functions of supervision in the CPSW practice setting is acknowledged globally (Aducci & Baptist, 2011; Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Department of Social Development (DSD) & South African Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSP), 2012; Green & Dekkers, 2010; Ingram, 2013). The mandatory role that supervisors play in supporting social workers and DSWs was recently acknowledged by the DSD and SACSSP (2012). In South Africa supervision in the social work context is defined as a "process whereby the supervisor performs educational, supportive, and administrative functions in order to promote efficient and professional rendering of services" (New Dictionary of Social Work, 1995). From this definition it is clear that the social work supervisor in South Africa (Botha, 2002) and elsewhere (Kadushin & Harkness, 2002) has a duty to fulfil three main functions, namely administrative, educational and supportive. The support function, which is concerned with emotionally supporting social workers, is the function in which resilience of South African DSWs could be promoted.

Recent studies found that supervision has been neglected in CPSW; furthermore, a key problem with existing supervision practices is that they are mainly deficit-based and consequently focus on the limitations and shortcomings with limited attention to emotional support (Bradbury & Jones, 2013; Carpenter & Webb, 2013; Russ et al., 2009). In addition, other researchers argue that it is professionally and personally dangerous if supervision of CPSWs does not meet the "empathic-containing function" (Gibbs, 2001:330; Goddard & Hunt, 2011). Current supervision practices in CPSW thus call for an alternative model that would balance the function of supervision, and separate managerial and professional supervision in order to enhance the emotional wellbeing of CPSWs (Beddoe, 2010).

There are different models of supervision and they are used across professions such as the police (Brehm & Gates, 1993), medicine (Kilminster & Jolly, 2000), counselling (Dunbar-Krige & Fritz, 2006; Ward & House, 1998) and education (Emde, 2009; Weiss & Weiss, 2001; Weigand, 2007). Similarly, the literature in social work reports the application of a few models and interventions in the supervision context, namely feminist supervisory practices (Green & Dekkers, 2010); a model for the co-creation of emotionally intelligent supervision (Ingram, 2013); a study participant-driven model using the International Association for Social Work Practice (Muskat, 2013); the collaborative affirmative approach (Aducci & Baptist, 2011); and reflective supervision (Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Paris, 2012).

Reflective supervision

Reflective supervision is recognised in social work (Emde, 2009), and its value was already highlighted as far back as 2001 (Gibbs, 2001; Johns, 1995). Paris (2012) underlined that enhancing social worker resilience could take place by means of reflective supervision. Similarly, Russ et al. (2009:331) suggested that there be an "increased use of reflective practice, supervision, on-going learning, and collaborative peer support in promoting resilience in child protection staff". For decades reflective supervision has been used - and is still being used - by professionals, amongst others, in education (Emde, 2009; Weiss & Weiss, 2001; Weigand, 2007), nursing (Driscoll & Teh, 2001) and social work (Bradbury-Jones, 2013; Gibbs, 2001; Grant & Kinman, 2012; Paris, 2012). Worldwide, authors have commented on the potential positive outcomes and need for reflective supervision in social work, and highlighted the direct relationship between reflection and resilience (Collins, 2008; Engelbrecht, 2013; Gibbs, 2001; Grant & Kinman, 2012; Russ et al., 2009). So far, however, we could not find any available scholarly articles or grey literature on guidelines to support South African DSW supervisors to reflectively promote the resilience of their supervisees. We therefore decided to embed prospective resilience-promoting guidelines for supervisors of South African DSWs within a reflective supervision model (Paris, 2012).

Resilience-promoting approaches

Given the complexity of resilience, enhancing resilience should be well planned within a suitable intervention approach. Three approaches to the promotion of resilience are identified by Masten, Cutuli, Herbers and Reed (2009) and include a risk-reduction approach, an approach attentive to assets and a process-orientated approach. The first focuses on reducing risk and aims to reduce exposure to adversity. The second is attentive to assets: this approach is interested in increasing the number and quality of resources. Third is a process-orientated approach that involves influencing processes that will improve the life of the person at risk, instead of merely limiting exposure to risks or increasing the number of resources (Masten et al., 2009). Although these approaches are aimed particularly at fostering resilience in children who are at risk, the principles may be applied to others at risk, such as CPSWs. The process-orientated approach was chosen as a reference for South African DSW resilience-promoting guidelines, since it is very unlikely that exposure to risks in CPSW would be reduced or that there would be an escalation in the availability of resources, especially in the context of South African DSWs. Such a process-focused approach could be implemented during CPSW supervision.

Russ et al. (2009) provided direction for the application of such guidelines, and he strongly argued that resilience processes in CPSWs could be used to build resilience in others. As such, a recent South African study explored resilience processes of South African DSWs (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014) and found that these professionals engage in four fundamental resilience-enhancing processes, namely practice- and purpose-informing creeds, supportive collaborations, constructive transactions and accentuating the positive (Truter, 2014). All four of these resilience processes can potentially be supported by DSW supervisors who are responsible for monitoring and supporting the emotional wellbeing of CPSWs (Botha, 2002; Kadushin & Harkness, 2002). Given these findings (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014), which suggest that South African DSW resilience relies on an investment by their social ecology, and in light of the mandatory role that supervisors play in supporting DSWs (DSD & SACSSP, 2012), this article focused only on the role of DSW supervision and the DSW supervisor as representatives of a social ecology (Ungar, 2012).

RESEARCH QUESTION

The research question that guided this study asked: What guidelines could be developed to assist DSW supervisors in promoting South African DSW resilience within reflective supervision?

METHOD AND PROCEDURE

This article draws on the findings of three individual studies, which we converted into guidelines. These studies included: (a) a systematic meta-synthesis of 13 qualitative studies which explored DSW risk and resilience across the globe; (b) a qualitative study pertaining to possible indicators of resilience in resilient DSWs as formulated by an advisory panel (AP) of social work experts; and (c) the stories of 15 South African resilient DSWs who shared their exposure to and experience of professional risks and their processes of adjusting to these risks (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014). From the meta-synthesis it was evident that very little attention has been paid to DSW resilience worldwide, despite detailed attention to the taxing nature of DSW and several calls for DSW resilience to be enhanced (Truter, 2014). The AP concluded that indicators of South African resilient DSWs might include a value-embedded life, personal strengths, and support networks (Truter et al., 2014). From the lived experiences of the 15 resilient DSWs, it was found that their resilience was a result of engaging in four resilience processes, namely practice- and purpose-informing creeds, supportive collaborations, constructive transactions and accentuating the positive. A salient observation we made was that these resilience processes were reciprocated between the DSWs and their social ecologies (for example, their families) and that these shared processes were, mostly, unequally weighted and, at times, equally weighted. What this means was that in some instances DSWs and their social ecologies invested an equal amount of energy in the process of inspiring resilience; yet at other times either the DSW or the social ecology invested more effort to initiate resilience (Truter, 2014). Evidently, these DSWs could adjust well to workplace adversities not only because they navigated towards, and negotiated for, support from their ecologies, but also because their social ecologies responded positively to the plea for support (Truter, 2014; Ungar, 2006). For DSW supervisors to use these findings meaningfully to promote DSW resilience, these findings needed to be transformed into practical resilience-promoting guidelines. A possible way of transforming such findings into relevant guidelines is explained below.

Development of guidelines

First we identified a framework within which guidelines could be rooted. Paris (2012) proposed an adapted model of reflective supervision (adapted from the work of Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985; Johns, 1995). We chose this adapted model (Paris, 2012) as a framework in which South African DSW supervisors could support South African DSW resilience, because this model specifically relates not only to social work but also to resilience enhancement. In his model Paris (2012) focuses on identifying feelings related to a specific event/situation, helping the individual to reflect on how he or she could have handled the event/situation better, and to use emerging knowledge to consider alternative ways forward (Weiss, 2001). We adapted this model so that it focuses on identifying situations in the DSWs' life that potentially introduce risks and helping the DSW to reflect on current resilience processes, along with the proposal (through reflective questioning) of alternative resilience processes that involved navigation towards, and negotiation with, their supportive social ecology (Ungar, 2006). Identifying ways of sustaining resilience processes is a further focus of our modified model. The model was also adjusted in terms of the labels of each stage and the contents of each stage: Stage 1 was originally labelled "Return to experience"; Stage 2 "Attend to feelings and identify potential risks"; Stage 3 "Re-evaluate the experience"; and Stage 4 "Learning". We modified the labels of Stage 2 "Attend to feelings and explore development of further potential risks" and Stage 3 "Evaluate existing processes of positive adaptation to risks". The labels of Stages 1 and 4 remained unchanged. See Figure 1 for a visual summary of theses stages.

Relevant literature and research findings (Truter, 2014) were utilised to direct the design of the guidelines. See Figure 2 below for a schematic representation of these research findings and how they align to the literature on resilience. The research data were originally coded to formulate themes and answer the former research questions (Truter, 2014). Secondary data analyses (Russel, Bernard & Ryan, 2010) of the data were done independently by both authors, followed by a consensus discussion (Schurink et al., 2011), after which reflective questions and actions were formulated.

RESILIENCE-PROMOTING GUIDELINES FRAMED BY REFLECTIVE SUPERVISION ENDORSED

The literature is clear on what would be regarded as an acceptable supervisory style in the context of reflective supervision, and several fundamentals in this regard are proposed (Adamson, 2012; Franklin, 2011). Because of the central role that the DSW supervisor will adopt during the implementation of the proposed resilience-promoting guidelines, we recommend fundamentals of reflective supervision, followed by key considerations that the DSW supervisor could take into account prior to the application of the resilience-promoting guidelines. Next, we outline the four stages of the adapted model (Paris, 2012), with resilience-promoting processes embedded in Stage 3.

Fundamentals of reflective supervision

Various researchers acknowledge that reflective supervision prefers process over content as well as experiences and personal reactions (Weigand, 2007). This entails that the supervisor needs to separate managerial and professional supervision, and promote a more collaborative and emotionally supportive atmosphere (Beddoe, 2010; Franklin, 2011). Therefore the supervisor should actively listen to emotional content, and assist the supervisee in examining and processing the emotional content (Lawlor, 2013) through reflective questioning. Dunbar-Krige and Fritz (2006) and Beddoe (2010) advocate that the supervisor should first establish a trustworthy relationship with the supervisee by adopting a non-judgemental attitude, as well as a realistic approach to the risks and challenges the DSW might experience. The cultivation of a trustworthy relationship that prioritises confidentiality and respects the uniqueness of each DSW is thus imperative.

Key considerations pertaining to resilience contexts and guideline stages

Throughout implementation of the proposed guidelines, the influence of time, context and culture on how DSWs at risk adjust to adversity must be taken into account (Adamson, 2012; Ungar, 2011; Ungar, 2012, 2013). The guidelines may therefore be adaptable and vary across different groups of DSWs, times and contexts, and DSW supervisors should be aware of this and apply accordingly, when attempting to promote DSW resilience.

To support supervisors in nourishing DSW resilience, we developed a set of reflective questions, relevant to each stage. Stage 1 allows for the DSW to determine which events or experiences he or she would like to discuss and to reflect on related feelings (Franklin, 2011). During the second Stage the DSWs' feelings about such events are explored in depth by allowing the DSW to reflect more specifically on feelings evoked by experiences (Gibbs, 2001; Lawlor, 2013 ; Weigand, 2007). The supervisor might then be better able to explore and assist the DSW to identify current risks and the development of further potential risks. Stage 3 will follow, when the DSW will reflect on, and evaluate, existing ways of either adapting positively or less so (Adamson, 2012). The supervisor may then apply guidelines to help the DSW reflect on alternative processes of systematically supported positive adaptation (Lawlor, 2013). Finally, Stage 4 offers the opportunity for learning and planning a way forward either to sustain resilience processes or to explore alternatives (Franklin, 2011; Russ et al., 2009).

STAGE 1: Return to the experience

In the first Stage the supervisor allows the DSW to relate to, and re-experience, emotionally significant events (presenting potential risks), such as work pressure, financial strain, challenges unique to DSW, psychological tension and exhaustion (Franklin, 2011; Weigand, 2007). Possible reflective questions and actions in the first Stage include:

• What recent work-related or personal events would you like to reflect on?

• Explore feelings on what happened and on what the DSW did.

STAGE 2: Attend to feelings and explore development of further potential risks

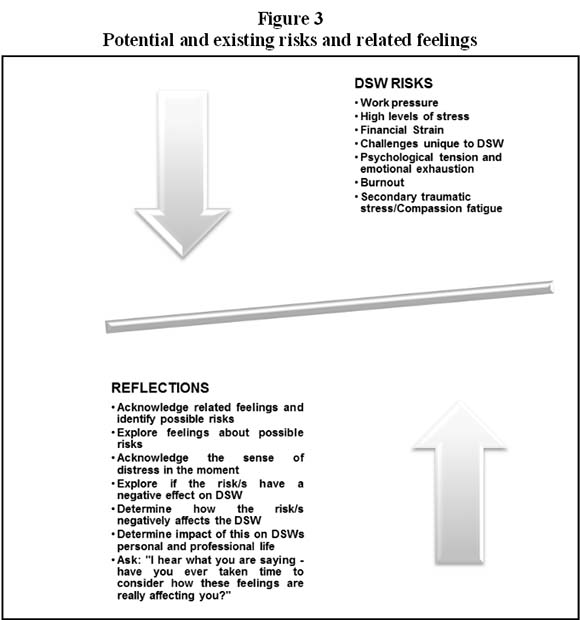

During the second Stage the supervisor should recognise negative feelings emanating from precarious events disclosed during Stage 1: evaluate the feelings, thoughts, intentions and actions evoked during those events (Gibbs, 2001; Lawlor, 2013; Weigand, 2007). The motive for this evaluation and recognition of negative feelings is that such feelings relate to threatening events that place the DSW at risk of negative outcomes (Benjamin, 2007; Child Welfare South Africa, 2009; Gibbs, 2001; Lonne, 2008; Maposa, 2006; Tham, 2006). During this stage, the supervisor will attempt to explore the development of further potential risks. Figure 3 below summarises reported risks in DSW (literature and research findings) and suggestions for reflection.

South African DSWs (Truter, 2014) identified the professional risk factors listed in Figure 3. These reported risks align with risks reported in other studies of CPSW risks (Truter, 2014). During this second Stage it is crucial for the supervisor to assist the DSW to explore and identify current or further potential risks that may develop. Often DSWs might be so overwhelmed that they do not realise when they are at risk and what the risk factors are. Therefore, the supervisor could play a key role to heighten awareness of further potential risk development (or recognition of existing risks) (Lawlor, 2013). Examining existing resilience processes and offering an opportunity to reflect on alternative resilience processes follow the exploration and identification of risk.

STAGE 3: Evaluate existing processes for positive adaptation to risks, and propose reflection on additional resilience processes

During the third Stage the supervisor encourages the DSW to reflect on existing processes of adaptation and provides the DSW with an opportunity to reflect on the value of such adaptation (Adamson, 2012). Possible reflective questions and actions to explore the value of existing resilience processes include:

• What did you do during this risk or event? How did it support your positive adaptation?

Following this reflection, attempt to enable the DSW to consider alternative resilience processes by asking the following potential reflective question:

• In which other ways could your dealing with such risks be enhanced?

The supervisor could then assist the DSW to identify which of the four resilience processes identified in the research findings and illustrated in Figure 1 need further promotion in the DSWs' life. This could be achieved by taking decisive action based on certain reflective questions (to the DSW).

Practice- and purpose-informing creeds

Rationale and application: a dominant process of resilience that emanated from research findings (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014) was the belief of having a calling to do DSW, and often the calling to DSW was related to the DSWS's religion (the Christian faith). The rationale, then, is to cultivate a purpose- and practice-informing creed as a resilience-supporting process.

What is important to note at this point is that (a) not all DSWs might have a sense of being called to do DSW; (b) not all DSWs will necessarily relate their calling or passion for DSW to faith or religion; and (c) not all DSWs will necessarily be Christian, as was the case with the DSWs in the study conducted by Truter (2014). The focus is therefore in the first place to explore whether the DSW does consider her/his position as a DSW to be a calling. Second, it is to remind the DSW of the meaning he/she ascribed to doing DSW and, third, if the particular DSW reflected on her/his work as a calling, to provide the DSW with an opportunity to renew the connection between being a DSW and having a calling.

It is imperative first to explore the application of existing resilience processes and allow the DSW to reflect whether these are adaptive or less so in his or her life (Russ et al., 2009; Adamson, 2012). The DSW supervisor may use reflective questions to encourage or provide the opportunity for self-discovery or rediscovery of the meaning ascribed to practice- and purpose-informing creeds to promote resilience in the DSW's life (Franklin, 2011; Lawlor, 2013). Ultimately, it is the DSW who needs to take decisive action, therefore heightened awareness (Walker-Williams & Fouché, 2015) of the shared responsibility that his/her social ecology has in promoting resilience is imperative.

Possible actions and reflective questions by the DSW supervisor include:

• The supervisor could encourage the DSW to reflect on why he or she became a DSW in the first place and what it means to him/her;

• What made you become a DSW? / How much of that motivation is still part of you?

• Why do you still practise DSW? Do your family, friends, and colleagues know about your calling/passion?

Examples of questions that may facilitate decisive action include:

• What have you become aware of in terms of whether you need to revisit your personal creed or not? Would you like to change anything in this regard?

Supportive collaborations

Rationale and application: Nourishing and relying on supportive relationships proved pivotal to DSW resilience (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014). The supervisor might therefore probe the existence of current supportive relationships in the DSWs' life and allow him/her to reflect on the support function and value of these relationships (Masten & Wright, 2010). Different options and choices (to nourish and use these relationships towards dweveloping resilience) are then explored with the DSW. The DSW supervisor may use reflective questions to explore existing supportive attachments as well as how the DSW is connecting with them, theirvalue for the DSW and possible promotion of this specific attachment. Ultimately, the supervisor will encourage the DSW to take decisive action by facilitating a heightened awareness (Walker-Williams & Fouché, 2015) of the shared responsibility that his/her social ecology has in promoting resilience.

Possible actions and reflective questions by DSW supervisor include:

• Exploring the function and meaning of significant relationships in the DSW's life, for example, friends, family and religious peers;

• Helping the DSW to reflect on these relationships and recognise the change that is necessary within these relationships and/or their value for his/her positive adjustment to workplace risks: If religion/spirituality is mentioned, then follow-up questions could be formulated;

• What do you do if you need to talk to someone?

• What would you want your friends/family/others to do when they become aware that you are not well?

• What do they normally do when they discover that you are not well? How do you prioritise time with family or friends?

Examples of question that may facilitate decisive action include:

• What have you become aware of in terms of the meaning that supportive collaborations have for you?

• What have you become aware of in terms of whether you need stronger supportive collaborations or not?

Constructive transactions

Rationale and application: At this stage the supervisor will attempt to encourage the DSW to actively engage in constructive transactions, such as: respecting personal needs and boundaries; investing in self-care activities; being solution focused; engaging in continuous training and education; and practising self-control.

First the supervisor could explore the application of existing constructive transactions and allow the DSW to reflect on whether these are adaptive or less so (Adamson, 2012; Lawlor, 2013). The supervisor may use reflective questions to explore how the DSW is making a connection with constructive transactions, their value for the DSW and possible promotion of specific constructive transactions. The supervisor needs to heighten the DSW's awareness of the shared responsibility that his/her social ecology has in promoting resilience.

Possible actions and reflective questions by DSW supervisor include:

- Exploring:

• How the DSW respects and maintains his/her emotional and physical boundaries;

• The DSW's need for, and the meaning of, self-care activities;

• The DSW's view of continuous training and education, and its value;

• The DSW's emotional self-regulation.

- Respecting personal needs and boundaries:

• How would you allow yourself to respond to the following situation: Your workload not allowing you to go home at the stipulated hour?

• How do your family, friends and colleagues help you to respect your own boundaries? Would you like to do this differently?

• If "Yes," how could you communicate this to them?

- Investing in self-care activities:

• What do you do for fun?

• What is the impact of this on your ability to adjust to stress at work?

- Engaging in continuous training and education:

• What does it mean for you when you attend workshops?

- Being solution focused:

• How do you handle problems generally?

• How would it support you to handle problems head-on and immediately?

- Practising self-control:

• How would you describe your ability to control yourself? Examples of questions that may facilitate decisive action include:

• What have you become aware of in terms of the meaning of constructive transactions for you?

• What have you become aware of in terms of whether you need constructive transactions or not?

Accentuating the positive

Rationale and application: "accentuating the positive" was an umbrella term applied to three resilience sub-processes that promoted positive adjustment (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014). These three sub-processes included the DSWs focusing on what they did achieve, a sense of humour, and purposefully selecting with whom they spent (positive) time. The supervisor could nurture these sub-processes of accentuating the positive (Gibbs, 2001).

First, explore the application of existing practices that emphasise the positive, and allow the DSW to reflect on whether they are adaptive or less so in the DSW's life. The supervisor may use reflective questions to explore how the DSW is making a connection with accentuating the positive, its value for the DSW, and the possible promotion of this specific process that emphasises the positive. Ultimately, it is the DSW who needs to take decisive action. Heighten the DSW's awareness of the shared responsibil ity that his/her social ecology has in promoting resilience.

Possible actions and reflective questions by the DSW supervisor include:

• Exploring the DSWs' view of what victories he or she experiences at work, even small victories;

• Allowing the DSW to reflect on who he/she considers positive company and the effect of such company on him/her.

- Celebrating victories:

• What does it mean for you when clients demonstrate that they are grateful?

• Could you share one success story you achieved with a client recently or in the past?

- Sharing humour:

• How does laughing or sharing humour affect you, and who are the people with whom you laugh the most, and how often do you see them?

- Choosing positive company:

• Describe the impact that spending time with positive people has on you? Example of a question to facilitate decisive action:

• What have you become aware of in terms of the meaning of accentuating the positive for you?

STAGE 4: Learning and planning

Although this Stage proceeds from Stage 3, it should be incorporated into all stages because, as a DSW develops awareness, learning and planning could follow. During Stage 4 the focus will be shifted from reflection to learning (Franklin, 2011). The supervisor could encourage opportunities for the DSW to consider what he or she has learnt with regard to existing processes of resilience. The DSW explains how these learning experiences will support him or her in future exposure to risks in order to adjust positively. "The supervisor should encourage the use of the professional understanding for professional growth, development and resilience promotion" (Weigand, 2007:18).

Possible reflective questions to encourage learning include:

• What have you learnt about your own adaptation to risk?

• What have you learnt about the role of your social ecology in supporting you to adapt to workplace risks?

The DSW could then be assisted to reflect on how these decisive actions could be applied and sustained to increase his or her chances of resilience. The supervisor might ask certain reflective questions to support the DSW towards such a plan of action.

A second set of possible reflective questions to nourish learning includes:

• How could you ensure the application of these decisive actions?

• How will you ensure the continuous application of these lessons throughout exposure to risk?

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this article was to formulate resilience-promoting guidelines for South African DSW supervisors to apply within a suitable framework of reflective supervision. Given the central role of a DSW supervisor in the professional life of a DSW, as well as the established support function of DSW supervisors, the DSW supervision relationship was selected as the setting in which these proposed guidelines could be implemented. Although the supervision model (Paris, 2012) from which this framework with guidelines was adapted has been verified and is based on established work (Boud et al., 1985; Johns, 1995), it cannot guarantee resilience promotion in South African DSWs. Still, the proposal of the guidelines is a first step toward supervisory support of DSW resilience.

Despite the resounding call to promote social worker (and DSW) resilience (Carson et al., 2011; Collins, 2007; Gibbs, 2001; Green, Gregory & Mason, 2003; Littlechild, 2003), not many DSW resilience-promoting guidelines have been formulated to integrate theory with practice. Resilience theories alone will not be sufficient to change the way in which these professionals adjust to the many risks they face. Practice has proven that the penalty of not promoting DSW resilience is high - with negative consequences for several stakeholders, including vulnerable children. Moreover, non-South African (Ungar, 2011, 2012) and South African (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014) studies point to the importance of social ecologies partnering with DSWs to support their resilience. Of concern is that resilient South African DSWs, more often than not, are the ones to initiate resilience-promoting engagement with their social ecologies, as opposed to their social ecologies reaching out and responding to the adversity in which most DSWs find themselves on a daily basis (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014).

Thus, by offering possible resilience-promoting guidelines for DSW supervisors and promoting a reflective supervisory context, the responsibility of the social ecology toward South African DSW resilience is foregrounded. DSW supervisors, as representatives of their social ecology, may use these guidelines to initiate and/or strengthen processes of South African DSW resilience. By asking pertinent reflective questions, DSW supervisors can heighten DSWs' awareness of their right to expect social ecological support. Thus, it is our strong recommendation that the suggested resilience-promoting guidelines within reflective supervision might be valuable and should be implemented within an appropriate programme and verified in different subgroups of DSWs across South Africa (Engelbrecht, 2013). Also, longitudinal studies should be implemented to determine the transferability of these guidelines.

LIMITATIONS

First, the proposed resilience-promoting guidelines have not been evaluated, and this calls for a follow-up study. Second, these guidelines are DSW focused. Even though they are to be facilitated by a DSW supervisor and even though they encourage reflection om the role of the social ecology in resilience processes, they do not engage the social ecology directly. Thus, there is a need for these findings to be translated into guidelines for families, colleagues, communities and so forth to support DSW resilience (Ungar, 2012).

These guidelines are based, in part, on empirical findings (Truter, 2014; Truter et al., 2014) that emanate from a meta-synthesis of only 13 qualitative studies, possible indicators of resilience in resilient DSWs as formulated by a small group of AP members, and a relatively small and homogenous sample (that is, 15 female, Christian South African DSWs). This could restrict the applicability of the guidelines to other DSWs (e.g. male atheists). Nonetheless, these proposed guidelines are a first step towards South African DSW resilience promotion with active input from a representative from their social ecology (i.e. DSW supervisors). This in itself is valuable, especially if follow-up studies investigate the practical value of DSW supervisors using these guidelines.

REFERENCES

ADAMSON, C. 2012. Supervision is not politically innocent. Australian Social Work, 65(2):185-196. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0312407x.2011.618544. [Accessed: 12/03/2014].

ADUCCI, C.J. & BAPTIST, J.A. 2011. A collaborative-affirmative approach to supervisory practice. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 23(2):88-102. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08952833.2011.574536 [Accessed: 12/06/2013].

AMRANI-COHEN, I. 1998. Resilience among social workers: a cross cultural study of Americans and Israelis. Boston: Boston College. (PhD Dissertation) [ Links ]

BECKETT, C. 2007. Child protection. An introduction. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

BEDDOE, L. 2010. Surveillance or reflection: professional supervision in "the risk society". British Journal of Social Work, 40(4):1279-1296. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://bjsw.oxfordjournals.org/content/40/4/1279 [Accessed: 01/02/2012].

BENJAMIN, J. March. 2007. Bursaries for SA's social workers. [ Links ]: [Online] Available: http://www.southafrica.info/about/social/social-270207.htm [Accessed: 01/02/2012].

BOSMAN-SADIE, H. & CORRIE, L. 2010. A practical approach to the Children's Act. South Africa: LexisNexis. [ Links ]

BOTHA, N.J. 2002. Supervision and consultation in social work. Bloemfontein: Drufoma. [ Links ]

BOUD, D., KEOGH, R. & WALKER, D. 1985. Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In: BOUD, D., KEOGH, R. & WALKER, D. (eds) Reflection: turning experience into learning. East Brunswick, N.J.: Nichols. [ Links ]

BRADBURY-JONES, C. 2013. Refocusing child protection supervision: an innovative approach to supporting practitioners. Child Care in Practice, 19(3):253-266. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13575279.2013.785937 [Accessed: 21/04/2013].

BREHM, J. & GATES, S. 1993. Donut shops and speed traps: evaluating models of supervision of police behaviour. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2):555-581. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.istor.org/stable/2111384 [Accessed: 10/07/2013].

BYRNE, M. P. 2006. Strengths-based service planning as a resilience factor in child protective social workers. USA: Boston College Graduate School of Social Work (PhD Dissertation) [ Links ]

CARPENTER, J. & WEBB, C.M. 2011. What can be done to promote the retention of social workers? A systematic review of interventions. British Journal of Social Work, 42(7):1235-1255. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bisw/bcr144 [Accessed: 16/03/2014].

CARSON, E., KING, S. & PAPATRAIANOU, L. 2011. Resilience among social workers: The role of informal learning in the workplace. Practice, 23(5):267-278. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09503153.2011.581361 [Accessed: 02/09/2013].

CHILD WELFARE SOUTH AFRICA. 2009. Response to media reports on the performance of Child Welfare Vereeniging and the conduct of their social workers. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.childwelfaresa.org.za/index.php/latest-news/125-child-welfare-vereeniging [Accessed: 01/02/2012].

COLLINS, S. 2007. Social workers, resilience, positive emotions and optimism. Practice, 19(4):255-269. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09503150701728186. [Accessed: 02/02/2012].

COLLINS, S. 2008. Statutory social workers: stress, job satisfaction, coping, social support and individual differences. British Journal of Social Work, 38(6):1173-1193. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://bisw.oxfordiournals.org/content/38/6/1173.short [Accessed: 02/02/2012].

CONRAD, D. & KELLAR-GUENTHER, Y. 2006. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among Colorado child protection workers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(10):1071-1080. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0145213406002286 [Accessed: 02/02/2012].

DOUGLAS, E.M. 2013. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress among child welfare workers who experience a maltreatment fatality on their caseload. Journal of Evidence-based Social Work, 10(4):373-387. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15433714.2012 .664058 [Accessed: 02/08/2013].

DRISCOLL, J. & TEH, B. 2001. The potential of reflective practice to develop individual orthopaedic nurse practitioners and their practice. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing, 5(2):95-103. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361311101901505. [Accessed: 02/08/2013].

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (DSD) & SOUTH AFRICAN COUNCIL FOR SOCIAL SERVICE PROFESSIONS (SACSSP). 2012. Supervision framework for the social work profession. Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DUNBAR-KRIGE, H. & FRITZ, E. 2006. The supervision of counsellors in South Africa. Travels in new territory. South Africa: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

EMDE, B.M. 2009. Facilitating reflective supervision in an early child development center. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(6):664-672. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/imhj.20235/full [Accessed: 05/05/2013].

ENGELBRECHT, L. 2013. Social work supervision policies and frameworks: playing notes or making music? Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 49(4):456-468. [ Links ]

FOURIE, C.L. & THERON, L.C. 2012. Resilience in the face of Fragile X Syndrome. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10):1355-1368. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://qhr.sagepub.com/content/22/10/1355.short [Accessed: 16/10/2013].

FRANKLIN, L.D. 2011. Reflective supervision for the Green Social Worker: practical applications for supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2):204-214. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.607743 [Accessed: 16/10/2013].

GIBBS, J.A. 2001. Maintaining front-line workers in child protection: A case for refocusing supervision. Child Abuse Review, 10(5):323-335. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/car.707/full [Accessed: 02/03/2011].

GODDARD, C. & HUNT, S. 2011. The complexities of caring for child protection workers: the contexts of practice and supervision. Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community, 25(4):413-432. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2011.626644 [Accessed: 02/01/2011].

GRANT, L. & KINMAN, G. 2012. Enhancing wellbeing in social work students: building resilience in the next generation. Social Work Education, 31(5):605-621. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02615479.2011. 590931 [Accessed: 05/02/2013].

GREEN, M.S. & DEKKERS, T.D. 2010. Attending to power and diversity in supervision: an exploration of supervisee learning outcomes and satisfaction with supervision. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 22(4):293-312. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2010.528703 [Accessed: 06/04/2013].

GREEN, R., GREGORY, R. & MASON, R. 2003. It's no picnic: personal and family safety for rural social workers. Australian Social Work, 56(2):94-106. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1046/i.0312-407X.2003.00075.x [Accessed: 10/04/2011].

GU, Q. & DAY, C. 2007. Teachers' resilience: A necessary condition for effectiveness. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8):1302-1316. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0742051X06001028 [Accessed: 10/04/2011].

HURLEY, D.J., MARTIN, L. & HALLBERG, R. 2013. Resilience in child welfare: a social work perspective. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 4(2):259-273. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://iournals.uvic.ca/index.php/iicyfs/article/view/12211 [Accessed: 04/03/2012].

INGRAM, R. 2013. Emotions, social work practice and supervision: An uneasy alliance? Journal of Social Work Practice, 27(1):5-19. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02650533.2012.745842 [Accessed: 05/04/2013].

JOHNS, C. 1995. Framing learning through reflection within Carper's fundamental ways of knowing in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22(2):226-234. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/i.1365- [Accessed: 17/06/2013].

JONES, C. 2001. Voices from the front line: State social workers and new labour. British Journal of Social Work, 31(4):547-562. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://bisw.oxfordiournals.org/content/31/4/547.short [Accessed: 05/04/2011].

KADUSHIN, A. & HARKNESS, D. 2002. Supervision in social work (4th ed). New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

KEARNS, S. & McARDLE, K. 2012. "Doing it right?" - accessing the narratives of identity of newly qualified social workers through the lens of resilience: I am, I have, I can. Child and Family Social Work, 17(4):385-394. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/i.1365-2206.2011.00792.x/full [Accessed: 13/07/2013].

KILMINSTER, S.M. & JOLLY, B.C. 2000. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: A literature review. Medical Education, 34(10):827-840. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/i.1365-2923.2000.00758.x/full [Accessed: 07/09/2012].

KIM, H., JI, J. & KAO, D. 2011. Burnout and physical health among social workers: a three-year longitudinal study. Social Work, 56(3):258-268. [ Links ] [Online]: Available: http://sw.oxfordiournals.org/content/56/3/258.short [Accessed: 14/03/2012].

KINMAN, G. & GRANT, L. 2011. Exploring stress resilience in trainee social workers: The role of emotional and social competencies. British Journal of Social Work, 41(2):1-15. [ Links ] [Online]: Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bisw/bcq088. [Accessed: 14/03/2012].

KOEN, D. 2010. Resilience in professional nurses. Vanderbijlpark, South Africa: North-West University. (PhD dissertation) [ Links ]

LAW, P. 2011. Inquiry likely into fears child could die due to social workers' "unmanageable" workloads. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/ wales-news/2011/11/05/inquiry-likely-into-fears-child-could-die-due-to-social-workers-unmanageable-workloads-91466-29721689/#ixzz1cvTA4qv8 [Accessed: 01/02/2011].

LAWLOR, D. 2013. A transformation programme for children's social care managers using an interactional and reflective supervision model to develop supervision skills. Journal of Social Work Practice, 27(2):177-189. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2013.7981 [Accessed: 08/07/2014].

LITTLECHILD, B. 2003. Working with aggressive and violent parents in child protection social work. Practice: Social Work in Action, 15(1):33-44. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09503150308416909 [Accessed: 07/03/2011].

LONNE, B. 2008. Child protection social work in Australia faces a crisis. International Federation of Social Work. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.ifsw.org/p38001585.html. [Accessed: 01/02/2011].

MAPOSA, S. 2006. Social worker shortage puts children at risk. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/social-worker-shortage-puts-children-at-risk-1.290278. [Accessed: 24/05/2011].

MASTEN, A.S. 2011. Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2):493-506. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://journals.cambridge. org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8255627 [Accessed: 02/03/2012].

MASTEN, A.S., CUTULI, J.J., HERBERS, J.E. & REED, M.J. 2009. Resilience in development. In: LOPEZ, S.J. & SNYDER, C.R. (eds) Oxford handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 117-131. [ Links ]

MASTEN, A.S. & WRIGHT, M.O. 2010. Resilience over the lifespan. In: REICH, J.W., ZAUTRA, A.J. & HALL, J.S. (eds) Handbook of adult resilience. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

MORRIS, L. 2005. The process of decision-making by stressed social workers: to stay or leave the workplace. International Review of Psychiatry, 17(5):347-354. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540260500238488 [Accessed: 02/02/2011].

MUSKAT, B. 2013. The use of IASWG standards for social work practice with groups in supervision of group work practitioners. Social Work with Groups, 36(2-3):208-221. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2012.753837. [Accessed: 02/05/2013].

NARAIN, J. 2011. Baby whose mother strapped him in front of fire for three days dies after social services missed 17 chances to save him. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1352864/Baby-dies-Manchester-social-services-miss-17-chances-save-him.html. [Accessed: 01/02/ 2012].

NEW DICTIONARY OF SOCIAL WORK. 1995. Cape Town: CTP Book Printers. [ Links ]

ONG, A.D., BERGEMAN, C.S., BISCONTI, T.L. & WALLACE, K.A. 2006. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4):730-749. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.9L4.730. [Accessed: 01/02/ 2012].

PARIS, A. 2012. Building resilience through reflection - Developing social workers and practice educators. Paper presented at a workshop at the University of Birmingham 6 July 2012. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/159794556/Building-Resilience-and-Reflection-for-Developing-Staff [Accessed: 17/06/2013].

PARGAMENT, K. I. & CUMMINGS, J. 2010. Anchored by faith: Religion as a resilience factor. In: REICH, J.W., ZAUTRA, A.J. & HALL, J.S. (eds) Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

RUSS, E., LONNE, B. & DARLINGTON, Y. 2009. Using resilience to reconceptualise child protection workforce capacity. Australian Social Work, 62(3):324-338. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03124070903060042. [Accessed: 04/06/2012].

RUSSEL BERNARD, H. & RYAN, G.W. 2010. Analyzing qualitative data. Systematic approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

SAYERS, J. 1991. Talking about child protection: stress and supervision. Practice, 5(2): 121-137. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09503159108411549. [Accessed: 04/06/2012].

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Qualitative data analysis and interpretation. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

STANLEY, N., MANTHORPE, J. & WHITE, M. 2006. Depression in the profession: social workers' experiences and perception. British Journal of Social Work, 37(2):281-298. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http ://bisw.oxfordiournal s.org/content/37/2/281.short [Accessed: 02/02/2011].

STOREY, J. & BILLINGHAM, J. 2001. Occupational stress and social work. Social Work Education, 20(6):659-670. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02615470120089843a. [Accessed: 05/05/2011].

SUMSION, J. 2004. Early childhood teachers' constructions of their resilience and thriving: A continuing investigation. International Journal of Early Years Education, 12(3):275-290. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0966976042000268735#.VSeEHiAaLIU. [Accessed: 02/06/2011].

THAM, P. 2006. Why are they leaving? Factors affecting intention to leave among social workers in child welfare. British Journal of Social Work, 37(7):1225-1246. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl054. [Accessed: 02/06/2011].

TRUTER, E. 2014. South African social workers at risk: exploring pathways to their resilience. Vanderbijlpark: North West University. (Thesis - PhD). [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dspace.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/10645.

TRUTER, E., THERON, L.C. & FOUCHÉ, A. 2014. Indicators of resilience in resilient South-African designated social workers: professional perspectives. Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 26(3):305-329. [ Links ]

TUGADE, M.M. 2011. Positive emotions and coping: examining dual process models of resilience. In: FOLKMAN, S. (eds) The Oxford handbook of stress, health and coping. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

UNGAR, M. 2006. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work, 38(2):218-235. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://mmr.sagepub.com/content/5/2/126.short [Accessed: 02/06/2011].

UNGAR, M. 2011. The social ecology of resilience: addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1):1-17. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x/full [Accessed: 20/07/2012].

UNGAR, M. 2012. The social ecology of resilience. A handbook of theory and practice. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

UNGAR, M. 2013. Resilience, trauma, context and culture. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 14(3):255-266. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://tva.sagepub.com/content/14/3/255.full.pdf+html [Accessed: 05/10/2013].

WALKER-WILLIAMS, H.J. & FOUCHÉ, A. 2015. A strengths-based group intervention for women who experienced child sexual abuse. Research on Social Work Practice. In Press. [ Links ]

WARD, C.C. & HOUSE, R.M. 1998. Counseling supervision: a reflective model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38(1):23-33. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1998.tb00554.x. [Accessed: 08/05/2013].

WEIGAND, R.F. 2007. Reflective supervision in child care. The discoveries of an accidental tourist. Zero to Three, 17-22. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.christina neumeyer.org/yahoositeadmin/assets/docs/Reflective Supervision.100194946.pdf [Accessed: 08/05/2013].

WEISS, E.M. & WEISS, S. 2001. Doing reflective supervision with student teachers in a professional development school culture. Reflective Practice, 2(2):125-154. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14623940120071343 [Accessed: 08/05/2013].

WOOD, L., NTAOTE, G.M. & THERON, L. 2012. Supporting Lesotho teachers to develop resilience in the face of the HIV and AIDS pandemic. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(3):428-439. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/i.tate.2011.11.009 [Accessed: 15/01/203].

YÜRÜR, S. & SARIKAYA, M. 2012. The effects of workload, role ambiguity, and social support on burnout among social workers in Turkey. Administration in Social Work, 36(5):457-478. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03643107.2011.613365 [Accessed: 02/02/2013].