Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.51 n.2 Stellenbosch 2015

http://dx.doi.org/51-1-442

ARTICLES

Exploring adolescents' participation in decision-making in related foster care placements in South Africa

Ulene Schiller

Department of Social Work and Social Development, University of Fort Hare, Alice, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Since the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted in 1989, children have a right to express their views and participate in matters concerning them. This aspect of participation is also encompassed in legislation in South Africa. This paper explores the participatory decision-making experiences that adolescents have relating to their foster care placements by conducting a qualitative research study. Findings indicate that a minority of adolescents were included in the decision-making processes. The paper concludes with findings for foster care and recommends that adolescents should be taken seriously in matters concerning them.

INTRODUCTION

In South Africa social workers in the field of child and family care are faced with the reality of child protection and statutory work focusing on foster care investigations on a daily basis. This is the result of diverse factors including the HIV/AIDS pandemic, poverty and unemployment in the country. According to the South African Social Security Association (SASSA) 2014 statistical report, 512 055 children receive foster child grants. Of these 512 055 children in foster care, 216 524 are adolescents between the age of 14 and 17 years (SASSA, 2014). The majority of adolescents in foster care in South Africa are in related foster care or the "kinship care" of their extended family (NWSSDF, 2007). Dealing with these high caseloads of adolescents in related foster care, social workers are often faced with issues such as behavioural problems and not wanting to attend school, which creates difficulties in their placements (Wessels, 2013). A need was expressed by social workers in the field to determine the experiences of adolescents in related foster care placements, as many adolescents come to a point where they no longer want to attend school or have any motivation to be in foster care any longer. A study done by UNICEF (2011) indicated children's right to participation is probably the least attended to globally. It was therefore decided that the aspect of participation in decision-making should be explored amongst adolescents in foster care. A study was conducted at a large non-governmental welfare organisation rendering welfare services in five of the nine provinces in South Africa.

WIDER CONTEXT AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF THE STUDY

In 1994, after the official end of apartheid, the South African government adopted the developmental approach to social service delivery. The developmental approach is based on the recognition of the strengths of the individual, groups or community and their capacity for growth and development (Department of Social Development, 2005:5). Patel (2008:73) describes developmental social work as a "pro-poor strategy promoting participation of the socially excluded in development activities to achieve social and economic justice, human rights, social solidarity and active citizenship." This position clearly stresses the need for participatory decision-making by those affected. In this context participation as defined by UNICEF (2011) is an "ongoing process of children's expression and active involvement in decision-making at different levels in matters concerning them according to their age and maturity."

According to Patel (2008), developmental social work consists of two core components which are central to its design. These core elements are sets of theoretical principles and a broad framework of reference for practice. The theoretical principles of the approach focus on five themes: a rights-based approach; socio-economic development together with building human capacity for people to participate in this socio-economic development; democracy and participation; pluralistic social development that engages role-players across diverse economic, social and institutional sectors; and the holistic analysis of social problems that go beyond local levels to consider global forces as well.

Social workers are encouraged in their practice to select and integrate approaches from the variety of theories in the social sciences and apply them together with social work skills and social work roles to complement their theoretical base. The skills, which operate at micro, mezzo and macro levels, should integrate general social work skills, but have commonalities in research; the design, planning, evaluation and programme management of interventions; and the mobilisation of people and resources. The roles include recognised social work roles such as advocate, facilitator, and educator. These principles have to be further supported by values that include social justice, ubuntu, equality, non-discrimination and reconciliation, competence, integrity, professional responsibility, recognising the importance of human relationships, and service (Patel, 2008).

The Children's Act 38 of 2005 (section 10) and the South African Constitution emphasise the participation of children in the matters affecting them. When implementing the developmental social work approach, the social worker should take into account the principles of self-reliance, empowerment and participation in delivering services to a child (Department of Social Development, 2005).

To contextualise the study further, it is important to understand the developmental stage of the adolescents in terms of their age, maturity and behaviour in foster care. This will provide a better understanding of the adolescent's behaviour in his/her specific context.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE AND BEHAVIOUR OF THE ADOLESCENT IN FOSTER CARE

Adolescents who enter foster care face various challenges. Not only do they have to deal with traumatic conditions or events that resulted in their placement in foster care, but they also have to cope with adjustment to life in alternative care. Early adolescence is characterised by high levels of peer influence, uncertainty of self and great instability in self-evaluation, which makes this a challenging phase of development (Brinthaupt & Lipka, 2002:4; Demo & Savin-Williams in Brinthaupt & Lipka, 2002:7; Dobson, 2005:178). Adolescents also experience many personal and emotional changes including mood swings, conflict with the family, heightened peer-group importance, body changes, the development of intense sexual feelings, and the developing and testing of values (Carter & McGoldrick, 1999:275; Pawlowski & Hamilton [sa]:1). These in turn have a complex effect on every aspect of adolescents' lives, including their relationships. This may include their relationships with family members, friends, their peers and teachers, as well as their relationship to school achievement and the prevalence of engagement in risky behaviours. Louw and Louw (2014) mention that adolescents make great advances in their cognitive development, such as starting to confront intellectual challenges that are part of their lives. Maturation of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence gives adolescents the ability to reject irrelevant information and formulate complex hypothetical arguments and to plan for their future. This highlights the maturity level of adolescents and their need to participate in decision-making processes. This information then possibly explains why foster care placements generally go well until the child reaches adolescence. At this developmental stage they start to question aspects regarding their placements and this is then often associated with or seen as behavioural problems.

Having discussed the policy and theoretical premises of the study, the next section presents the research process and methods that were used in this study.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This was an exploratory study and the type of research was applied in nature with the goal of exploring the participatory decision-making experiences of adolescents in related foster care. A qualitative research approach was employed, which Delport, Fouché and Schurink (2011), indicate helps researchers to understand people and the social and cultural context in which they live. A collective case study design was used so that comparisons between the cases and concepts could be made. In this way, as suggested by Mark (1996 in Delport et al., 2011:322), theories can be extended and validated by the comparison of the different cases.

The study was conducted at the Suid-Afrikaanse Vroue Federasie (SAVF) welfare organisation (NGO), which concentrates, amongst other services, on child protection work. In a survey done by Schiller (2012) on the services provided by this organisation, the majority of the social workers' caseloads was statutory work or legal social work services concentrating on investigations and placing children in alternative care. Further analysis of their caseloads revealed that most of the social workers' interventions consisted of foster care investigations focusing on kinship placements. In accordance with the Children's Act 38 of 2005, which regulates the welfare needs of all children in South Africa, kinship placements were those in which children are placed in foster care with immediate or extended family members (Children's Act, 38 of 2005).

A non-probability, purposive sampling design was used whereby participants were selected based on availability and characteristics that served the study best (Terre Blanche, Durrheim & Painter, 1999). The sample was comprised of 35 adolescents in related foster care who were between the ages of 13 and 18 years. The demographic areas of these adolescent participants ranged from urban to rural settings. All participants and their caregivers were well informed about the purpose and goal of the study and signed assent and consent forms. All interviews were conducted by qualified social workers. Information was gathered anonymously and ensured privacy and confidentiality. If any participant needed extra emotional support, they would have been referred.

Data was collected by means of face-to-face interviews with the research participants over a period of a year. Interviews were conducted at the homes of the participants by the different fieldworkers in the various provinces. A semi-structured interview was used that consisted of basic themes which covered the following: participants' biographical data, participation decision-making in terms of the initial placement, participation during the placement, their needs in terms of social service delivery in their placements as well as a focus on their future.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analysed using qualitative data-analysis techniques as described by De Vos, Strydom, Fouché and Delport (2011).

• Planning for recording of data: all data were recorded by using a digital voice recorder during all interviews. All fieldworkers who collected the data were sufficiently trained in using the semi-structured interview schedule and how to record the data.

• Data collection and preliminary analyses: data were collected during interviews using a semi-structured interviewing schedule. All interviews were transcribed after the interviews were conducted.

• Managing or organising the data: data were managed and organised by using Microsoft Excel.

• Reading and writing memos: transcripts were read and memos were made.

• Generating categories, themes and patterns: categories were designed, and themes and patterns that emerged were identified.

• Coding the data: all the data were coded and sorted under the different categories and themes.

• Testing the emergent understandings and searching for alternative explanations: regular meetings and discussions with fieldworkers were held to test emergent understanding. This also contributed to the trustworthiness of the data as regular peer debriefings were held.

• Writing the report: writing of the report and feedback was given to the organisation.

Trustworthiness as described by De Vos et al. (2011) was promoted by ensuring transferability with the triangulation of multiple sources of data. Using fieldworkers and also making use of peer debriefing contributed to the trustworthiness of this study. Cross-referencing of data gathered by the interviewers was continuously done to ensure consistency as well as to ensure the optimal credibility of the research data-gathering and data-analyses processes. Dependability (reliability) was ensured as a logical research process was followed and a steady audit trail was kept throughout the research process.

The findings in this study were derived from a qualitative inquiry with a small sample of adolescents in related foster care and thus the findings should not be assumed to represent the larger population of such adolescents. It is therefore important to introduce the characteristics of the study participants. The findings of the study will be discussed according to the different themes and sub-themes that were derived from the data.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

The research participants will be introduced under the relevant categories below.

Characteristics of study participants

Age

All the participants were between the ages of 13 and 18 years, which is the age range for adolescents. Louw and Louw (2014) are of the opinion that, depending on the biological and socio-cultural factors as well as on individual differences, the developmental stage of the adolescent varies from the starting age of 11 to 13 years and ends between 17-21 years. In this study, however, the 13-18 age range was used.

Duration of the current placement

The duration of the participants' current placements varied from one year to 14 years. The average duration was three to five years. Most of the participants were settled in their placements, with only a few still adjusting. A minority of the participants had been in previous placements and were placed with new carers a second time. Shin (2009) mentions that an unstable living environment is created when adolescents frequently experience placement changes and these factors were considered in the data-collection process.

Biological parents

Seventy-four percent of the adolescent participants in this study had lost one or both of their parents. This is a significant contributing factor to possible behavioural difficulties that these adolescents may experience. Wieruszowski (2009) mentions that when a child loses a parent it has implications for the child such as the possible placement in alternative care which leads to issues relating to identity and rejection. The child might be reluctant to adapt to the new situation and the lifestyle and values of the new placement may differ dramatically from those to which the child was accustomed. This could limit growth and add to the child's grief and a lack of a sense of belonging.

Foster parents

All the foster parents were related to the participants either as immediate or extended family members, which the Children's Act 38 of 2005 refers to as "kinship placements". A significant factor in these arrangements was that half of the respondents were placed in the care of their grandparents. These parents often experienced difficulty in controlling their foster children's behaviour and found it difficult to enforce rules and discipline. It was also difficult for some older foster parents to relate to the children and to provide them with the educational assistance they needed. Participants staying with their grandparents, however, showed a great amount of love and respect for them and felt that they were a source of strength and knowledge for them. This is captured in the remarks of one of the participants, who responded to the question of how s/he felt about staying with a grandparent by saying, "It is the best thing that they could have done after my parents passed on."

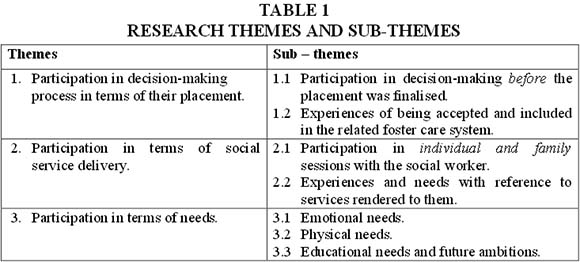

RESEARCH THEMES AND SUB-THEMES

As described earlier, the data that had been collected were coded and sorted under different themes. The following table highlights the themes and sub-themes derived from the findings. With the focus on the construct of participatory decision-making with reference to the related foster care placement experiences of adolescents, non-related themes were discarded for the purpose of the study. As suggested by De Vos et al. (2011), the themes will be introduced and described, and the sub-themes will be described with reference to quotations and by contextualising them within the relevant literature.

DISCUSSION

Theme 1: Participation in the decision-making process

Developmental social work emphasises that children should participate in the decision-making process, which would also contribute to their self-determination (Department of Social Development, 2005). Furthermore, pluralistic social development engages role players across diverse economic, social and institutional sectors. Thus the role players in the lives of foster adolescents should include the foster adolescents themselves. According to Section 10 of the Children's Act, it is stated that: "every child that is of such an age, maturity and stage of development as to be able to participate in any matter concerning that child has the right to participate in an appropriate way and views expressed by the child must be given due consideration."

The following sub-themes are divided into before the placement has been finalised and after the placement has been finalised. The social worker conducted an investigation in terms of section 155 of the Children's Act to determine if a child is in need of care and protection, and where the most suitable placement for the child would be, should the child no longer be able to stay in the care of his/her parents. This investigation is conducted before the placement is finalised. After that a court order is made and a child in this study would be placed in related foster care and the social worker should deliver supervision services; thus in sub-theme 1.2 the aspects of participation in the decisionmaking process after the finalisation of the placement are explored.

Sub-theme 1.1: Participation in the decision-making process before their placements were finalised

A minority of the participants indicated that they were asked about their views in the decision-making process regarding their foster care placement. These participants noted that their family made the decision on where they should stay on their behalf and they were not asked to participate in the decision-making process at all. One participant, for example, indicated s/he was not consulted by the social worker at all in the process of his/her placement.

Many participants were of the opinion that the other available family members were their only other care option and they didn't participate in a decision as to where they would like to be placed. One of the participants specifically mentioned: "I didn't feel good at all as I wasn't so young when my parents passed on. The life that I was living changed as I just had to live with my grandmother." During an interview with experts in the field it was mentioned that the aspect regarding the participatory decision-making phenomena places the social worker in a difficult situation at times as in different cultural groups the family members and community at large would make a decision according to what is acceptable in their culture and not necessary including the adolescent in the decision-making process (UNICEF, 2011). The family would then dictate to the social worker as to how the social worker should act (Van Deventer, 2013). Although this practice is unacceptable and not according to what is prescribed by legislation, it is a reality that is important to take note of.

It was clear in the interviews with the participants that they wished to be included in decisions regarding their placements. According to some of the participants, the social worker was seen as somebody "who assists the family to get access to a foster care grant" - thus the focus is on a monetary benefit, and not on listening and including the participants in the decision-making process. A study by UNICEF (2011) mentions that children's right to participation in matters affecting them is probably the least attended to globally. One of the participants in this study confirmed this notion mentioning: "They never involved me in the discussion ... the adults made the decision and I felt I just had to go along with it." A sense of frustration was sensed amongst the participants who were not included in the decision-making process.

The fact that adolescents do not participate in the placements in which they are expected to function is contrary to the principles of the developmental social work approach, which is considered to be a rights-based approach (Patel, 2008).

Half of the participants felt that the removal and initial placement were a positive experience. Most of the adolescents understood foster care to be the term for a place you stay when you cannot live with your parents.

Sub-theme 1.2: Experiences of being accepted and included in the related foster care system

However, there is not only a negative side to the current service delivery process. In this study the majority of the children being placed with families mentioned that the families made them feel at home and part of the family. One of the participants mentioned this saying, "I wasn't even aware that I was placed in foster care" as he felt he was part of the family. Participants also mentioned: "They made me feel part of them from the beginning" .

Theme 2: Participation in terms of social work service delivery

According to a study done by Gerrand and Ross (2009), a large number of children in South Africa are entering the child protection system via statutory intervention into permanent kinship care. This reality is also emphasised in SASSA's statistical report (2014) - it places a huge strain on the child protection system in terms of effective service delivery to all participants.

The Children's Act, 38 of 2005, states that all children in foster care need to be visited by a social service professional at least once every two years in order to monitor and evaluate the placement. Social services are rendered to individuals and families, in groups and communities (Department of Social Development, 2005). In the following section sub-themes are divided in terms of the different methods of social work service delivery.

Sub-theme 2.1: Participation in individual and family sessions with the social worker

The participants had very definite needs and issues which they felt had to be addressed by a social worker. One of the participants mentioned that they wanted the social worker to attend to their "real needs". Participants were also of the opinion that the social workers should visit them more at home and not see them only at the social workers' offices.

A study by Perumal and Kasiram (2009:202) on adolescents likewise found that social workers often just visited them during holidays, when the social workers would secure holiday visits to their families of origin or host families. These visits did not include psycho-social support and therapeutic services. Moodley (2006) argues, therefore, that social workers in the South African context appear to be ill equipped and under-resourced to meet these challenges.

In this study many participants felt that: "foster parents should be guided and supported regarding discipline and raising foster children", as one put it. They also mentioned that: "They (the social workers) should try and get as close to the family as they can, like with the foster parenting, they should understand and help the foster parents to understand the children better." This coincides with the finding of a study conducted in Spain by Montserrat (2014) that found the support received by kinship care families is deficient in comparison with the support that other protection resources receive.

Sub-theme 2.2: Experiences and needs with respect to services rendered to them

Some participants mentioned that: "social workers should arrange more motivational programmes that can help them deal with peer pressure." Some of the participants mentioned that they would enjoy being in groups with other foster children so that they can learn from one another. They further mentioned they "would like to see the social worker not only when they need to renew the court order". Social workers have high case loads and often attend to foster children only when they need to review their cases to renew the court order (Van Deventer, 2013). It was clear from quite a few participants' experience that they had a need for more contact with the social worker.

Theme 3: Participation in terms of their needs

As mentioned by Holland (2001), adolescents who experience trauma and loss are prone to behavioural difficulties that can affect the wellbeing of the foster child and foster families. At times it is difficult to work with these adolescents and to ensure that they participate in addressing what their needs are in their placements.

Sub-theme 3.1: Physical needs

Many of the participants mentioned that the foster parents look after them and bought them what they needed. Most of the participants could reflect only on their physical needs. There were some participants, especially the older adolescent participants, who could define emotional needs and one participant mentioned: "They provide for my basic needs but when it comes to love, it is not enough - they are not emotionally there for me when I need to talk or discuss how I feel."

Sub-theme 3.2: Emotional needs

The majority of the participants could not define emotional needs and they got confused between emotional and physical needs. It is clear that many of the participants felt that they were not getting the emotional support they needed. There seemed to be a number of fears among these participants. They were unsure about their future and did not know that they were protected under the Children's Act, as they were aware that they were in foster care only until they turned 18 years old or finished their schooling. This created insecurities amongst some of the foster adolescents. One participant mentioned: "I'm scared what happens when I finish my schooling and my granny passes on - I will have no support to further my studies; the foster care grant will lapse, what then?"

In a research study conducted by Altshuler (2003) it was found that stability in a child's life is the key factor to ensuring that the child feels like he or she belongs, and is loved and cared for by their foster parents. Furthermore, this researcher found that the children who experience being loved and cared for by their foster parents achieved higher academic results, had better social interactions, improved on their family connections and generally had a better sense of wellbeing.

Some participants mentioned that they had a sense of belonging and felt part of the family. Some of the children said: "It feels like home" and mentioned that they experience love and support. Most of the participants felt loved and supported and, although there is friction with the foster parents at times, this is seen as part of the normal developmental phase of the adolescent and is experienced with biological

children as well as the foster children. As stated by Louw and Louw (2014), the adolescent life phase is challenging, and is marked by periods of friction, change and problems, but when understood correctly, the adolescent period can be a good developmental stage for the individual and the people involved.

Sub-theme 3.3: Educational needs and future ambitions

From the findings it appears that most of the adolescents struggle academically. They openly dislike subjects that they do not perform well in. They admit they require extra support in these subjects and a few of them attend extra classes.

Most of the participants felt that their foster parents supported them and want the best for them when they leave school. One of the participants said: "I believe my foster parents support me, they take the lead, they help me to make decisions." Another participant mentioned that: "They have a positive influence in my life and it motivates me to work hard. " Participants who received support and guidance from their foster parents aspired to hopes and dreams for the future. Those participants who did not receive support and guidance often tended to have fears and experience uncertainties. Participants showed a lot of resilience, as some mentioned that: "my background will not influence my future but rather motivate me ".

Some of the participants said they do not get enough support in schooling - they need the foster parents to help them and the foster parents were often not in a position to assist them with their school work. This was due to a generation gap and the low educational levels of the foster parents. The literature suggests that foster adolescents are discharged from foster care without proper training and preparation for independence and that a large number of foster adolescents do not have detailed plans for independent living (McMillen & Tucker, 1999 in Shin, 2014).

Most of the participants had aspirations to further their education and pursue tertiary education, although they felt very unsure. A study done by Tilbury, Buys and Creed (2009) indicated that foster adolescents needed additional support as they transition out of care. They also indicated the importance of supportive relationships and self-determination.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this research was to explore what the participatory decision-making experiences were of adolescents in related foster care. The theoretical framework that formed the basis of this research was the developmental approach to social service delivery. Data collection was done by having face-to-face interviews using a semi-structured interviewing schedule with adolescent participants conducted in five of the nine provinces in South Africa.

It was clear from the findings in the study that participants wanted to be included in the decision-making process, e.g. participants mentioned: "I would like to share my experience that they (social workers) can understand us ", adding that: "I feel it is unfair to us if they don't listen to us". Scannapieco, Connell-Carrick and Painter (2007) rated the inclusion of foster adolescents in the decision-making process as the most important

theme in their research. The same view is also echoed in this study. It is further evident that in South Africa social workers are bearing unmanageable caseloads, which possibly contributes to the exclusion of participants from the decision-making process.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Streak and Poggenpoel (2005:6) and Patel (2008) emphasise that a developmental approach to social service delivery should incorporate integrated multi-prolonged interventions that build self-reliance and foster participation in decision-making at individual, family and community level. If social workers are to follow the developmental social work principles, as stated by Patel (2008), of being an advocate, facilitator and educator, they would need to ensure that the adolescent is included in the decision-making process. The social worker should educate foster parents with relevant knowledge using the development approach to enhance their understanding of how they can contribute to assist the adolescent to participate in the decision-making processes.

Increasing numbers of foster care placements are putting a lot of strain on the welfare system in South Africa, specifically on service delivery. The National Department of Social Development should redeploy more social workers to render services to families and not only to ensure that investigations are finalised so that social security benefits can be paid to the families, but also ensure that the constitutional right of the children to effective protection against maltreatment is met. This should also be implemented in line with the Framework for Social Work Services (Department of Social Development, 2013), in that social workers should work with manageable caseloads and sufficient supervision services.

Working with adolescents as a vulnerable group and specifically with those who endure trauma requires specialised skills and dedicated time from the social worker. It is therefore recommended that social workers ensure that adolescents in foster care are included in the decision-making process from before the placement until they exit the foster care system. Such participation (cf. Section 10 of the Children's Act) in the decision-making process should assist in contributing to the development of self-reliance and the empowerment of the individual (Patel, 2008). It can be recommended that additional training can be done with social workers to emphasise the importance of participatory decision-making and the value that this will add to addressing inclusiveness and the development of self-reliance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge the Director of Social Work Services, the managers, social workers and the service users of the SAVF, who contributed to the successful completion of this research project.

REFERENCES

ALTSHULER, S.J. 2003. From barriers to successful collaboration: public schools and Child Welfare working together. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(1):52-63. [ Links ]

BRINTHAUPT, T.M. & LIPKA, R.P. 2002. Understanding early adolescent self and identity: applications and interventions. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

CARTER, B. & McGOLDRICK, M. 1999. The expanded family life cycle: individuals, families and social perspectives (3rd ed). USA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

CHILDREN'S ACT 38 of 2005. Government Gazette. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

DE VOS, A.S. (ed), STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2011. Research at grassroots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 545. [ Links ]

DELPORT, C.S.L., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Theory and literature in qualitative research. In: DE VOS, A.S. (ed), STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. Research at grassroots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 545. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2005. Integrated Service Delivery Model. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2013. Framework for Social Service Delivery. Pretoria. [ Links ]

DOBSON, J. 2005. Die eiesinnige kind: praktiese raad oor hoe om 'n kind met 'n sterk wil te hanteer. Vereeniging: Christelike Uitgewersmaatskappy. [ Links ]

GERRAND, P. & ROSS, E. 2009. Permanent kinship care via court-ordered foster care: is this system justified? The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 21(1):4-22. [ Links ]

HOLLAND, J. 2001. Understanding children's experiences of parental bereavement. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

LOUW, D.A. & LOUW, A.E. 2014. Child and adolescent development (2nd ed). Bloemfontein: Psychology Publications. [ Links ]

MONTSERRAT, C. 2014. Kinship care in Spain: messages from research. Child & Family Social Work, 19:367-376. [ Links ]

MOODLEY, R. 2006. The challenges confronting social workers in meeting the objective of permanency planning at children's homes in the magisterial district of Durban. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. (MA Thesis (Social Work)) [ Links ]

NWSSDF (NATIONAL WELFARE SOCIAL SERVICE AND DEVELOPMENT FORUM). 2007. Use of the statutory foster care system to support long term kinship care: impact on the social welfare system and the social work profession. Discussion paper. [Online] Available: http://www.pmg.org.za/docs/2007/070919nwssdfdiscus.htm. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2008. Getting it right and wrong: an overview of a decade of post-apartheid social welfare. Practice: Social Work in Action, 20(2). [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0950315080205882. [ Links ]

PAWLOWSKI, W., ACSW & HAMILTON, G. [Sa]. Stages of Adolescent Development. [ Links ]

PERUMAL, N. & KASIRAM, M. 2009. Living in foster care and in a children's home: voices of children and their caregivers. The Researcher-Practitioner, 45(2):198-206. [ Links ]

SASSA (SOUTH AFRICAN SOCIAL SECURITY ASSOCIATION). 2014. Statistical Report. [Online] Available: http:/www.sassa.gov.za/applications/cms/documents/file[Accessed: 07/08/2014]. [ Links ]

SCANNAPIECO, M., CONNELL-CARRICK, & PAINTER, K. 2007. In their own words: Challenges facing youth aging out of foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24:423-435. [ Links ]

SCHILLER, U. 2012. Survey on Social Service Delivery at the SAVF. Unpublished study. [ Links ]

SHIN, S.H. 2009. Improving social work practice with foster adolescents: examining readiness for independence. Journal of Public and Child Welfare, 3:354-371. [ Links ]

STREAK, J. & POGGENPOEL, S. 2005. Protecting children where it matters most: in their families and their neighbourhoods. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 41(1):27-37. [ Links ]

TERRE BLANCHE, M., DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. 1999. Research in practice: applied methods for social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

TILBURY, C., BUYS, N. & CREED, P. 2009. Perspectives of young people in care about their school-to-work transition. Australian Social Work, 62(4):476-490. [Online] Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.108/03124070903312849. [ Links ]

UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: UN General Assembly. [ Links ]

UNICEF (UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND). 2011. Every Child's Right to be Heard. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

VAN DEVENTER, C. 2013. Personal interview with Mrs Van Deventer, Regional Manager, Suid-Afrikaanse Vroue Federasie. 5 May. Pretoria. [ Links ]

WESSELS, T. 2013. Personal interview with Mrs Wessels, Regional Manager, Suid-Afrikaanse Vroue Federasie. 17 April. Pretoria. [ Links ]

WIERUSZOWSKI, L.C. 2009. The experiences of adolescents dealing with parental loss through death. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (MA (Social Work)) [ Links ]