Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.51 no.1 Stellenbosch 2015

http://dx.doi.org/51-1-430

ARTICLES

"If a person uses alcohol the real you comes out": Exploring the self, sexual experiences and substance abuse

Jacques BotesI; Rinie SchenckII

IDepartment of Social Work, University of South Africa

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The article aims to describe the role substances play in relation to the experiences of the self and sexual behaviour of the substance users, which may be of significance for the rehabilitation process. Based on Carl Rogers's person-centred approach, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a voluntary sample of seven participants in a treatment centre in Pretoria, South Africa. The findings suggest that the use of substances assists the individual in relieving psychological tensions and to experience euphoric sexual encounters in the process in a way that is congruent with the self-perception. These aspects needs to be taken into consideration in the treatment regimen.

Those who do not have power over the story that dominates their lives, the power to retell it, deconstruct it and change it as times change, truly are powerless, because they cannot think new thoughts (Salmon Rushdie, 1993. The Rushdie letters).

INTRODUCTION

Throughout history sexual activities have seemed to offer more than sexual gratification. In Babylon the king and priests engaged in sexual rituals to guarantee rain for their crops (Vos & Human, 2007). Vos and Human (2007) further describe that the philosophers of the Old Testament believed that fulfilling sexual relationships contributed to their experience of life as meaningful and that sexual pleasure served as a reward for soldiers returning from the battlefield, and offered emotional comfort to many people. A night of sexual pleasure, it was written, would give comfort and revitalise people for the next day's demands, and also served the purpose of alleviating anxiety about death (Vos & Human, 2007). As sexual pleasures facilitate escape from everyday realities and discomforts, so does the use of substances generate experiences of relief and escape through the euphoric effects of chemical substances and sedation (Erlank, 2002). It seems as if negative emotional affect can be avoided or buffered by both substance use and sex.

Indications of the link between substance use and sexual experiences were expressed by William Shakespeare in Macbeth (II.iii:29): "It (drinking) provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance ... it makes him and it mars him; it sets him on and it makes him off; it persuades him and disheartens him; makes him stand to and not stand to...". Holcombe (2006:990) further states that in the Deuterocanonical Testament of Judah verse 14 it is written: "for wine turneth the mind away from the truth, and kindleth in it the passion of lust ... for the spirit of fornication hath wine as a minister to give pleasures to the mind; for these two take away the power from a man".

Keane (2004) summarises the above views and notes that chemical substances as well as sexual acts can provide pleasure and create release or escape from internal discomfort as a way of regulating one's feelings and sense of self. Furthermore, in a review of the literature on alcohol use and sexual functioning in women, Sobczak (2009) argued that substance use can have an enabling and suppressant function in sexual encounters. Sobczak (2009) further mentions that alcohol may contribute to unpredictable sexual behaviour in women and suppress testosterone levels, which appears to decrease sexual desire in men. Androgens have been reported to increase sexual desire both in men and women (Sue, Sue & Sue, 2003). Medications, hypertensive drugs and alcohol have been noted to affect sexual desire. In this regard, Sue et al. (2003) have classified and described chemical substances according to the effects they have on the central nervous system (CNS) as follows:

- Alcohol, barbiturates and benzodiazepines are referred to as "depressants" or "sedatives", which are central nervous system depressants as they induce sleep and facilitate relief from anxiety;

- Amphetamines, caffeine, nicotine and cocaine are classified as "stimulants" as they energise the CNS and create euphoria and alertness;

- Marijuana, LSD and PCP are labelled as "hallucinogens" as they have the ability to induce hallucinations, heighten sensory awareness and result in "good/bad trips".

Exploring the relationship between substance abuse and sexual activities and the function both serve for the person was the aim of the research, as limited research has shown that the connection between the two activities is an important factor in the rehabilitation process of the substance user.

From the literature it seems therefore that both sex and substance abuse provide opportunities to escape negative experiences, but there is also an indication that substances may enhance or supress the sexual drives and experiences. The exploration of the function of substance abuse in the experiences of the self and sexual activities is the focus of this study, which may be of significance for the rehabilitation process of the person using substances.

THEORETICAL APPROACH

The theoretical approach used was Carl Rogers's person-centred approach (PCA) to guide the research process and to understand and explain the experiences of the participants, as the literature on this subject is limited.

The person-centred approach deals with the self or identity of the person (Rogers, 1987) and the following propositions formulated by Rogers (1987) were significant in this study:

- The self of the person is seen as the conception of who he or she is as a person (Proposition 8);

- This conception is formed in interaction with others (Proposition 9);

- If experiences threaten the person's perception of who he/she is, this creates psychological tension ( Proposition 14); and

- A person becomes well adjusted when experiences can be symbolised in a way that is congruent with the person' self-perception (Propositions 15, 18 and 19) (Grobler, Schenck & Mbedzi, 2013; Rogers, 1987).

These selected propositions provided guidelines towards understanding and ordering the data collected from the participants to make sense of the function of the substance abuse of the participants for the self and their impact on sexual activities.

METHOD

The research was conducted in a Rehabilitation Treatment Centre for substance abuse in Pretoria, South Africa. A qualitative research approach and an exploratory research design were used. Qualitative research is described by Creswell (2009:249) as a process that "explores a social or human problem and [in this way] the researcher builds a complex, holistic picture, analyses words, reports, detailed views of the informants and conducts the study in a natural setting." An exploratory design, according to De Vos, Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2011) and Creswell (2009), collects data and gains insight into an unknown area. A voluntary sample was recruited from the individuals undergoing in-patient treatment in the clinic. The in-patients attending the clinic were invited to participate if they could relate to the research topic. The patients were invited during their group and individual therapy sessions, where they were provided with verbal and written invitations outlining what the research is all about.

Seven individuals volunteered to be interviewed and signed the consent forms. No decisions on inclusion or exclusion of participants according to race, culture, gender, marital status, age or substance of choice were made. It was assumed that the voluntary participants were sexually active and could contribute to the focus of the study. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were applied as a method of data collection. Interviews lasted about an hour-and-a-half. Two participants were requested to have second interviews to obtain additional information. The interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and translated into English as some of the participants were Afrikaans speaking (Creswell in De Vos et al., 2011; Langford, 2001). Wong and Poone (2010) promote the transparency of the translation process. Only the English versions are presented here. Both authors agreed on the correctness of the translations.

Tesch (1991) explains that qualitative data analysis is a process of taking apart or de-contextualising, sifting and sorting the information gathered during the process of data collection. The five steps explained by Terre Blanche, Durrheim and Painter (2006) were used in analysing the data:

1. The familiarisation with, and immersion and developing of, ideas and theories;

2. Inducing themes where themes arise naturally from the data;

3. Coding by breaking up data in analytically relevant ways;

4. Elaboration by exploring themes more closely, and

5. Interpreting and verifying from other perspectives and literature. The person-centred approach guided the process, as very little literature is available to support or contrast with the findings.

The data were independently analysed by two coders, whose findings corresponded. The data were further triangulated with the literature and the person-centred approach. Although the sample size was small, data were sufficiently supportive to answer the question we set out to answer (Terre Blanche et al., 2006). Rich data emerged from the interviews, which were analysed into two themes and five sub-themes, which will be discussed in the following section.

RESULTS

The Participants

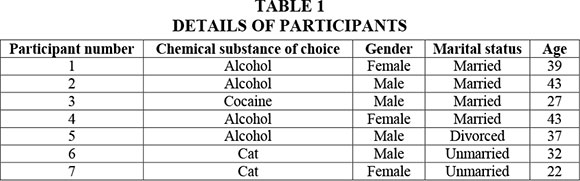

The participants were four men and three women. One male and one female had never been married, another male had been divorced for eight months and the other four participants were all married. Their ages ranged from 22 to 47, making the average age 38. Chemical substances of choice for the participants included cocaine, alcohol and Cat. Table 1 contains the details of the participants.

An overview of themes

Two major themes with sub-themes emerged from the conversation with the participants.

Theme 1: The function of substance abuse for the self.

Sub-theme 1. 1 Substance abuse provided relief from psychological tension.

Sub-theme 1.2 Substance abuse enabled experiences of acceptance and building relationships.

Sub-theme 1.3 Substance abuse assists in preservation of the self in sexual interactions.

Theme 2: The function of substance abuse for the sexual experiences of the person.

Sub-theme 2.1 Substance abuse allows sexual fantasies and risky sexual behaviour.

Sub-theme 2.2 Substance abuse enhances sexual pleasures.

Theme 1: The function of substance abuse for the self

Rogers (1987:498) explained the concept the self as "an organised, fluid but consistent conceptual pattern of perception of characteristics and relationships of the 'I' or the 'me'", in other words it is the person's conception of who he/she is as a unique human being (Grobler et al., 2013). A person's identity is the core of their existence and most of their behaviour is consistent with this self-concept. The question then arises what role substance abuse can play in the self-concept of the person.

Sub-theme 1.1: Substance abuse provides relief from psychological tension

Psychological tension, according to Rogers (1987) and Grobler et al. (2013), are thoughts, needs or emotions which a person experiences that do not fit with their symbolised or conscious self. This implies that inner conflict develops in the person. The participants stated that chemical substance abuse facilitated relief from the psychological or emotional discomfort resulting from this tension between the person and his/her external world. One participant stated: "Yes, my father suspected my sexual orientation and when he found out, he was furious and said he was going to beat it out of me; he said he didn't raise a pansy (gay person), so yes, this made it all worse because you sit with this in your head. " The participant continued to explain how he attempted to deal with the conflict of being gay and with the non-acceptance by his father: " when I was about 25/26 I was engaged to a girl. I gave it my all, my heart and soul, but I know I am different; I have been gay since I was in Grade Two ... and I have a big secret, one which I have carried with me for years ... I found a group of friends in Johannesburg who sort of accepted me ... because I am gay". The participant tried to fit the expectations of his father, but the resulting incongruence with regard to his authentic self led to psychological tension. The adopted values and the behaviour expected by his father and broader society were not owned by the participant. The substance use not only served as a relief from the emotional or psychological tension, but brought acceptance from others (friends) as an added valuable function (Grobler et al., 2013; Rogers, 1987).

Another participant also shared her psychological tensions as her husband expected anal sex, which was inconsistent with her sense of herself. She shared that she could deal with it when she was drunk: "I don't know if other men does it, but he (husband) punishes me by insisting on anal sex ... he knows I hate it, so he says it is my punishment if I do wrong. So, being passed out, helped". Any experience that is inconsistent with the self is perceived as a threat (Rogers, 1987) and the actions which cannot be incorporated into the self became bearable when she was inebriated.

Furthermore, some participants shared that their conservative upbringing created conflict or psychological tension between what others expected them to be and their experiences of self: "My mother always said if you masturbate you will go blind... and then I had to get glasses in primary school! I always suffered guilt and when I masturbated ... my mother always made me feel guilty about it". The function of the substance abuse then assisted him to masturbate without feeling guilty, as he described: "Like when you grow up you realise it is a natural thing and then you can go overboard when you are drunk ... you feel you have lost out because of the upbringing that you had and you feel that you now have much to make up for".

Another participant continued to refer to a "conservative" upbringing as creating psychological tension between what is expected by others and the self, as the substance abuse assisted in deafening the outside voices: "morality, moral values ... grew up very conservatively and was a good example ... the headboy ... it causes that the Cat (drug) silences the conservative upbringing ... dad's voice saying that he didn't raise a pansy ... and you can enjoy it for what it is ... sex ... without all the noise in your head ... everything is filed and gone... locked away for the evening".

This theme demonstrated that persons utilise chemical substances to escape and relieve psychological tension, emotional discomfort and experiences of non-acceptance. This finding is supported by Zastrow (2004) and Mudavanhu and Schenck (2014), who report that people use illicit drugs as a way of avoiding stressors in their lives and to create a sense of happiness. The person may not be consciously aware of the discomfort or the psychological conflict. Altering the brain chemicals with substances may bring relief from the conflict between the internal and external factors that created psychological tension (Barlow & Durand, 2005; Grobler et al., 2013; Rogers, 1987). The verbatim responses indicate that sexual development and issues related this (i.e. conservative upbringing, being homosexual, etc.) caused psychological tension, which was relieved through substance use and which is an important aspect to take into consideration in treatment. The participants did not feel that they could live up to expectations of the "others" and did not feel accepted and good enough, which emerged in the second sub-theme.

Sub-theme 1.2: Substance use enables experiencing acceptance and building relationships

Not being able to be who you are, and living with adopted values from parents or other significant others (Grobler et al., 2013; Rogers 1987; Wade & Schenck, 2012) created psychological tension and made it difficult for the participants to feel accepted when sober. Acceptance, according to the Oxford Dictionary, can be defined as "approval, belief or toleration", which implies a judgement (Grobler et al., 2013). If a person experiences acceptance or non-acceptance it means he/she does or does not fit into the other person's value system. Substance abuse provides the person with enough confidence to interact with people, in particular sexual interactions, and seeks approval: '"you will sit and if you're high and the guy sits in front of you ... then you fantasise yourself horny into something with the guy or two guys at once, yes, it has happened before that I told a guy everything that I wanted to do with him, or two guys at once. If I sit here and think back, I wonder how on earth I could do it? ... I enjoyed it so much ... imagine I was sitting here and I am horny for you (researcher), I am too shy now, but back then I took Cat, then I would have kissed that you know had been kissed... I would have been able to tell you straight what I wanted to do with you as well. I would have been able to tell you exactly how I felt and said we should go to the room, but as I sit here now, never". Not being able to be congruent with their selves made interpersonal interactions or relationships difficult as they do not know who they are, and whether they are acceptable the way they are. Being on substances provides courage to interact with others and feeling accepted: "I was accepted, it was awesome ... the Cat gave me self-confidence ... I was fine and energetic and confident, but in a good way, everyone liked me ... they loved me, I had a personality ".

Another participant confirmed: ''To help you feel acceptable ... they phone you to say let' s go have a drink, they phone you, flip you feel wanted. You know, I think it made me feel more acceptable then" .

The following participant described how he functioned when drunk: "I think I saw my personality more back then, if I had alcohol in me I had a smoother tongue, I could talk my way around things easier and get into a woman' s head and if she was intoxicated, well then, then it was even easier. We could communicate nicely, put some music on and dance ... oh yes how lovely. You bond easier if both have had a few drinks ".

In Proposition 11 Rogers (1987) explains the experiences of the participants of not feeling accepted. Non-acceptance is experienced as threatening to the self and refers to an inner conflict between how people see themselves and not being accepted the way they want to be. This refers to the person's self-esteem, which Louw and Louw (2007) describe as a person experiencing him/herself as valuable. Not being valued results in low self-esteem, which is seen as a risk factor for substance abuse (Louw & Louw, 2007). Instead of dealing with the non-acceptance or of not being valued on a conscious level, the substance use assists the participants to 'relate' to people and feel accepted. It is interesting that in sub-theme 2.1 it emerged that despite the fact that the participants were experiencing acceptance and contact, it was contact with no commitments and/or lasting attachments.

Sub-theme 1.3: Substance use enables attempts to preserve the self and enhance sexual interactions

In the discussion of the first sub-theme we referred to Rogers's (1987) Proposition 10, which explains that there are experiences and values integrated congruently into the self-structure of the person, but there may be values which are adopted from others. These values are "perceived in distorted fashion" (Rogers 1987:498). The inner conflict that develops between the self and the adopted values then creates psychological tension. The person does not own his or her experiences and behaviour, and the locus of control is not located within the person (Rogers, 1987). The inconsistent experience is seen as a threat to the self, and the person then attempts to preserve the self through substance use. "I don't always want to do the right thing like my mom said little girls should be ... I am probably not the perfect daughter today, here I sit in rehab ... oh, fuck it is probably true ... I will never be perfect... Why am I only good enough when I drink? ... it is the only time I feel okay ... free to do what I want ... I feel sexy, my body is fine ... I am good, I can give a man pleasure and can enjoy... I am only good enough when I drink... "

The following example further illustrates the external locus of control which exists as the reason for using substances: "I feel sometimes it is a demon that needs to be fed with wizza (whiskey) and good sex and then I go on a spree again ... usually stopped by my thoughts of my kids and X's (husband's) bitching and moaning... I don't know ... I guess it is first the horniness driving me to drink ... I can't figure having an exciting sex life without the drink... I really need to relax at times, the demon ... be myself".

It seems that the sexual interaction and the substance abuse heighten the sexual experiences, bring relief for the psychological tension and assist in their experience of acceptance, preserving and being and accepting themselves. According to Rosdahl and Kowalski (2008), Van Eeden, 2002) and Nace (in Erlank, 2002), chemical substances directly affect the human central nervous system and result, amongst various other effects, in a euphoric state of awareness, experiences of relief, relaxation, escape, euphoria and sedation, and can serve as a further motivation for future substance use.

Theme 2: The function of substance abuse in sexual experiences

Sub-theme 2.1: Substance abuse "allows" people to live their sexual fantasies and engage in risky behaviour

Participants indicated that engaging in risky sexual relationships provide experiences of being accepted; however, they could not accept risky sexual behaviours as part of the construct of self when they were sober. The participants reported that they did not take ownership of their behaviour when intoxicated and could then embark on risky sexual behaviours and fantasies. This notion is supported by Tapert, Aarons, Sedler and Brown (2001), Mudavanhu and Schenck (2014) and the World Drug Report (2008), who confirmed that substances users tend to engage in risky sexual behaviour which they would not have done otherwise. Some of the participants shared that when chemical substances were used, certain behaviours were "allowed": "and he looked like one of those fucker men that would do it good and hard and leave ... no attachment; exactly what I wanted and he made me so horny". A male participant further confirmed that he would act on sexual fantasies when under the influence of alcohol: "I went to Teazers (a nightclub) or whatever, what you wouldn't do if you were sober... And do, not just think, but have the courage to actually go and do it ... 'cause then you are brave, you have courage, you can go and do it. And women, I have seen it a lot, they are prim and proper, but as soon as they have alcohol in, then they are horny ... then the wheels come off, then there is no more primness" .

Participants also explained: "Wouldn't have done when I was sober ... Then I would have, as they say, 'Dutch courage' to do whatever I think of, what I normally would not have done. That' s what I realised about myself and saw with many other people ... but I fantasise about stuff ... there are things that I fantasise about that my husband won't do ... like two guys at the same time, but oh well, it'sprobably better that I am sober ... my husband will definitely leave me ". And: ''if a person uses alcohol the real you comes out ... whether you want to admit it or not. All those things that you fantasise about and suppress, when you use alcohol those inhibitions disappear ... you throw it overboard and you ... the real you appears ".

Another participant elaborated: " Dammit, I can really get kinky when I am pissed ... I like guys with nice cocks ... big... I guess ... can't believe I said that... Well it is said ... I'm not gay, but... when you are horny ... a couple of drinks I then start thinking what a guy drinking with me ... what ... if he has a nice bulge in his pants, what it looks like... how big he is ... If I am pissed, I guess I always had fantasies about men ... being pissed makes me then bi(sexual) at times. "

A study done on men at gay and bisexual clubs concluded that MDMA or ecstasy (stimulant) abuse was connected with high-risk sexual behaviour among some gay and bisexual men (Klitzman, Pope & Hudson, 2000). Furthermore, the participants explain the enhancement of sexual pleasure as a result of the use of chemical substances, as will be explained under the next theme.

Sub-theme 2.2: Substance abuse enhances sexual pleasure

The chemical alteration of central nervous system processes (Barlow & Durand, 2005) allows biological enhancement of sensory perception and impulses from the environment. The participants shared the pleasures and excitement of sex when using drugs: "totally awesome ... there is no orgasm like an orgasm on Cat... I promise you, it is incredible, ten times better, more intense compared to normal... it is unbelievable ". One also explains that it is not only heightened the experience but it enhances the duration of the sexual experience: "it' s better than you would normally do it, you get more satisfaction for a longer period when you are on Cat" . The participants share that they could prolong the duration of sexual experiences as well as the pleasure associated with these sexual acts. Chemical substances would further enhance the sexual experience to be more pleasurable and allowed the person to experience heightened pleasure.

It was further reported that when using substances, they felt more confident about their physical appearance and less concerned that they would be unattractive to others. Internally (chemically), substance use alters the awareness, numbs inhibitions and eliminates adopted values from others and, in so doing, facilitates pleasurable experiences for the person: " It' s probably the way in which they touch you and touch you for longer ... the satisfaction is better, it's longer, where you normally have sex, its over quickly, but if you are on Cat you can carry on for hours, you take a break, smoke a cigarette and carry on. You are also not shy to do what is good and of your body ".

The numbing/elimination of inhibiting factors, combined with biological enhancement, creates an euphoric perception of experiences for the person. Participants using stimulants such as Cat reported heightened sensory awareness and perception: "your skin ... everything is more sensitive ... it is awesome if someone just touches you ... You are very sensitive ... wow, if someone just walks past you and slaps your bum, it normally doesn' t bother you or you think they are joking if someone puts their hand on your leg ... , your sex drive goes berserk." The same participant explains further on the euphoric experience while using Cat: " You see, your whole body feels different, if someone touches you, you get goose pimples, oooh ... if someone hugs you, it is such a tantalising feeling that you feel over your whole body, it' s amazing. The physical sensation of it, its good... awesome, it's sexual and sensual... Your whole body feels good".

Chemical substances enhance sensory stimulation up to a euphoric level of extraordinary experience, according to the participants. Touch and feel were explained as super-sexual experiences. The enhanced euphoric experience held further facilitative functions for the person and the rewards experienced included heightened self-esteem, acceptance by others, recognition of the self as well as the temporary reconstruction of the self as being acceptable and attractive to one's self and to others.

The participants shared that the fantasies were brought to the experiential level, but the implication was that they would not be able to experience the same euphoric pleasure without the use of chemical substances (Sobczak, 2009; Sue et al., 2003). In this study the female participants indicated that alcohol would enhance sexual arousal and would then facilitate pleasurable sexual experiences: "You know, I think it also goes in phases, if you start ... in the beginning phase of drinking, then it turns you on ... you, your hormones go through the roof. Then it decreases again, I mean the amount that you drink and the constant drinking ... you can't go scrape your hormones off the ceiling every day. But in general, you do... the opposite sex looks more acceptable to you and it makes you more ... and if they still give you attention then you suddenly feel attracted to the guy. But right throughout my life I can see (alcohol) awakened something in me ".

Sobczak (2009) draws attention to unexpected or unpredictable sexual behaviour when persons, especially women, are under the influence of chemical substances. Whether the substance user's substances of choice were stimulants or suppressants, the substance use was found to be facilitative the satisfaction of the person's sexual and relationship needs.

Participants were aware of certain needs that were satisfied by means of combining sexual acts with chemical substance use, but most were not aware that there were deeper underlying unsymbolised needs. For some, the self was perceived as powerless and unattractive when sober, but participants explained that they had learnt how to chemically manipulate the psychological perception of the self. They further symbolised the need to "discover the true self" by numbing their current awareness. This allowed enhanced sexual interaction with others and new experiences into the concept of self: "the Cat lifts your sex drive enormously, incredibly ... I never had a very high sex drive, maybe because it was always such a taboo subject for me, but on Cat it was a different story; it sexually charges you, you are charged up ... I would be far more relaxed and open in a club. Also, I had huge issues about my body, but if there was a guy and he, he leads you on, then I would just go with him, no problem ... it was okay, fine and I did actually have a drive ".

Based on the above it can be argued that euphoria is biologically generated by the sex act and in order to enhance the euphoric state, the central nervous system is chemically stimulated to release even more dopamine. The reverse could also happen, where the chemical euphoric state is improved by adding sex to the formula. The above assumption can be stated in the following short formula (Fig. 1).

The figure illustrates that chemical substances result in heightened euphoria (++), while sex also provides heightened euphoria (++). Together they result in super-experiences (++++) of euphoria. In other words, the person has now experimented and reached the conclusion that substances create euphoria and by adding sex the euphoria can be increased to a "super"-euphoric state.

This last sub-theme explained that individuals discover that they can add value to their sexual experiences by using chemical substances. A chemical substance-induced euphoric state could thus be heightened by adding sexual pleasures or vice versa. This provides even more relief for psychological tension and provides heightened experiences of acceptance, albeit very temporarily, unattached and unsymbolised.

CONCLUSION

Two main themes with their sub-themes were highlighted in this article, which supports the notion that substance dependence is a complex phenomenon, with deep-seated personal experiences of not being good enough, experiences of non-acceptance and conflict between who the person is (the self) and outside expectations. The use of substances alters experiences and engaging in risky sexual behaviour is used to relieve psychological tension and heighten acceptance of the self and of others.

Rogers (1987) and Grobler et al. (2013) explain that a person reacts as an organised whole to the external world of experiences. The whole of the person refers, among other things, to the emotions, actions, experiences, perceptions and values of the person. The findings suggest that the psychological tension, the need for acceptance and being themselves, the substance abuse and the sexual experiences are interconnected in the process to fulfil the need to be congruent and be accepted who they are. The implication for practice is a process of facilitating the symbolisation of the substance users/abuser's psychological tension and discovering and accepting the self, their experiences, perceptions and actions; as a participant stated: "The experience here [in the treatment centre] is actually a good one ... being connected with myself again. While drinking ... I really was not in contact with myself or anyone else" .

What became apparent from the interviews was that the self was constructed according to values adopted from others (parents or community). Participants reported that they were able to control or ignore these adopted values through substance abuse and their sexual behaviour. These adopted values were not necessarily congruent with and owned by the person. The need arises to suppress these values ("morals") without experiences of guilt or shame (psychological tension). The substance abuse and sexual actions supported this process.

The implication for the process of change thus involves the facilitation of a process where the individual perceives and accepts, into the self-structure, more symbolised and owned experiences, and discovers that he/she can reinstate his/her own value system and behaviour (Grobler et al., 2013; Mearns & Thorne, 2013; Rogers, 1987; Tolan, 2012). The development of the individual's own value system is no longer based upon experiences which have been symbolised in a distorted way, but rather as a continuing of their own valuing process (Rogers, 1987). Individuals will trust themselves and make their own decisions in the process of self-reconstruction (Sternberg, 2001). Durrant and Kowalski (1990) confirm that counselling should enhance a person's self-definition (Mearns & Thorne, 2013; Tolan, 2012). Ultimately, the purpose of counselling is to assist a client to experience realness and change, and this is facilitated by creating conditions which are growth-promoting and free from external judgements (Grobler et al., 2013; Mearns & Thorne, 2013; Rogers, 1987, 1995; Tolan, 2012).

This study indicates that there are multiple elements that threaten the self and that the person is not always able to significantly view the self consciously as experienced. The need to be valued and respected is of paramount importance to persons, as are the symbolised development and maintenance of the self-structure (Tolan, 2012; Wade & Schenck, 2012). Once experiences are symbolised and accepted into the structure of the self, then reorganisation of self-structure and an integrated functioning of the self can be facilitated (Grobler et al., 2013). The individual should thus be able to grow and change in a facilitative environment free from threat to the self, which will assist the individual to have the power to construct and reconstruct his/her own story. As Rushdie says: "to have power over the story that dominates their lives, the power to retell it, deconstruct it and change it" - to be able to have new experiences, thoughts and behaviours.

The findings suggest that the use of substances and sexual activities assists the individual in relieving psychological tensions. The "super"-euphoric experiences as described by the participants should be taken into consideration in the holistic treatment process and become part of the symbolisation and reconstruction process of the person.

REFERENCES

BARLOW, D.H. & DURAND, V.M. 2005. Abnormal psychology, an integrative approach. London: Thomson Wadsworth. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2009. Research design, qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2011. Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: JL van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

DURRANT, M. & KOWALSKI, K. 1990. Overcoming the effects of sexual abuse: developing a self-perception of competence. In: DURRANT, M. & WHITE, C. (eds) Ideas for therapy with sexual abuse. Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications. [ Links ]

ERLANK, E.C. 2002. Die substansafhanklike geneesheer, 'n maatskaplikewerk-perspektief. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (Unpublished doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

GROBLER, H., SCHENCK, R. & MBEDZI, P. 2013. Person-centred facilitation: process, theory and practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HOLCOMBE, A.O. 2006. Provoking the desire. The Lancet, 368 (9540):990. [ Links ]

KEANE, H. 2004. Disorders of desire: addiction and problems of intimacy. Journal of Medical Humanities, 25(3): 189-204. [ Links ]

KLITZMAN, R.L., POPE, H.G. & HUDSON, 2000. MDMA (Ecstasy): abuse and high risk sexual behaviour among 169 gay and bisexual men. American Journal Psychiatry, 157(7):1162-1164. [ Links ]

LANGFORD, R.W. 2001. Navigating the maze of nursing research: an interactive learning adventure. London: Mosby. [ Links ]

LOUW, D.A. & LOUW, A.E. 2007. Child and adolescent development. Bloemfontein: Psychology Publications. [ Links ]

MEARNS, D. & THORNE, B. 2013. Person-centred counselling in action (3rd ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

MUDAVANHU, N. & SCHENCK, C.J. 2014. Substance abuse amongst the youth in Grabouw Western Cape: voices from the community. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 50(3):370-391. [ Links ]

ROGERS, C.R. 1987. Client-centred therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. London: Constable. [ Links ]

ROGERS, C.R. 1995. A way of being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

ROSDAHL C.B. & KOWALSKIE M.T. 2008. Textbook of basic Nursing. Philadelphia: Lippencott, Williams and Wilkens. [ Links ]

RUSHDIE, S. 1993. The Rushdie letters: freedom to speak, freedom to write. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press [ Links ]

SHAKESPEARE, W. 1954. Macbeth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

SOBCZAK, J.A. 2009. Alcohol use and sexual function in women: a literature review. Journal for Addictions Nursing, 20(2):71-85. [ Links ]

STERNBERG, R.J. 2001. Psychology, in search of the human mind (3rd ed). Fort Worth: Harcourt College Publishers. [ Links ]

SUE, D., SUE, D.W. & SUE, S. 2003. Understanding abnormal behaviour (7th ed). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. [ Links ]

TAPERT, S.F., AARONS, G.A., SEDLER, G.R. & BROWN, S.A. 2001. Adolescent substance abuse and sexual risk-taking behaviour. Journal of Adolescent Health, 28(3):181-189. [ Links ]

TERRE BLANCHE, M., DURRHEIM, K. & PAINTER, D. 2006. Research in practice, applied methods for the social sciences (2nd ed). Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

TOLAN, J. 2012. Skills in person-centred counselling and psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

VAN EEDEN, A. 2000. Drugs, facts arguments and practical advice. Pretoria: Doctors for Life. [ Links ]

VOS, C. & HUMAN, D. 2007. Liefde is die grootste, oor erotiek en seksualiteit. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. [ Links ]

WADE, B. & SCHENCK, R. 2012. Trauma is the "stealing of my sense of being me": a person centred perspective on trauma. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 48(3): 1-17. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME. 2008. World drug report. [ Links ] [Online] Available: https://www.google.co.za/7gwsrd=ssl#q=unodc+2008+world+drug+report.

WONG, J.P.H. & POONE, M.K.L. 2010. Bringing translations out of the shadow: translation as an issue of methodological significance in cross cultural qualitative research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(2):151-158. [ Links ]

ZASTROW, C. 2004. Introduction to social work and social welfare: empowering people. Belmont CA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]