Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.4 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-4-390

ARTICLES

Identification and initial care process of child victims of transnational trafficking: A social work perspective

Ajwang' WarriaI; Hanna NelII; Jean TriegaardtII

IPhD candidate; Department of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg

IIDepartment of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Child trafficking violates children's rights and undermines their protection. Under-identification of child victims of trafficking has been reported to be a challenge globally and in South Africa. This article illustrates the process a social worker could apply when identifying child victims of transnational trafficking. Findings of the qualitative research reveal that there is no single point of entry for a trafficked child and thus there can be several actors in the identification process; it was also found that initial care and protection are also essential. The role of social workers in the identification-assessment-care process is highlighted.

INTRODUCTION

Child trafficking violates children's rights and undermines their protection. The way that child trafficking is defined is of great significance in its identification, management and prevention. An attempt at a more comprehensive international approach was made by the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (2000), also known as the UN Trafficking Protocol or the Palermo Protocol. In the definition of trafficking, this protocol acknowledged that children under the age of 18 years cannot give consent to exploitation. Subsequently, this definition was effected in the South African Prevention and Combating Trafficking in Persons Act (henceforth referred to as "Trafficking Act") (2013) to ensure that protection also extends to trafficked children. Section 4(1)(2) of the Trafficking Act provides the definition of trafficking and denotes that child trafficking is the movement of a child either within, into or out of South Africa, forcefully or not, with the purpose of exploiting the child. This definition also includes children who are adopted legally or illegally, or forced into marriage for purposes of exploitation.

However, in spite of the internationally acknowledged definition, the terms, issues and identification indicators around child trafficking continue to be points of confusion conceptually in policy and practice, even in South Africa (Loff & Sanghera, 2004). This confusion tends to affect the rapid identification of victims. Under-identification of child victims of trafficking has been reported to be a challenge globally, as indicated in international studies by Bump and Duncan (2003), Farrell, McDevitt and Faly (2010), Fong and Cardoso (2010), Gozdziak (2010), Gozdziak and MacDonnell (2007), Hepburn and Simon (2010), Hopper (2004), Oketch, Morreau and Benson (2012), Rigby and White (2013) and Sigmon (2008).

Worldwide, it is estimated that 1.2 million children are trafficked each year (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2007). Children's rights, which are fundamental to their growth and development, are violated when trafficking occurs. Child victims of trafficking, whether trafficked domestically or across borders, are subjected to the same harmful treatment as adults. Therefore, their age makes them more vulnerable to the harmful consequences of the abusive exploitative practices. Child victims generally feel the direct impact of trafficking. However, it is worth noting that the consequences of trafficking also extend to the child's family, community and country as a whole. Although these trafficking consequences are clearly outlined, in reality, they cannot be so readily compartmentalized or discussed in isolation. The ecological perspective can be used to explain the significant and complex interrelationships, influences and overlapping factors within each area of impact (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Friedman & Allen, 2010). Thus, the consequences of child trafficking may both contribute to and/ or influence each other in diverse ways and they are often closely interwoven.

This article is part of a doctoral study and sets out to identify the persons responsible for the identification of trafficked children. It is divided into three main sections: firstly, an overview of child trafficking in South Africa and identification of child victims of trafficking is presented. Next, the research methodology is outlined and the findings arising from the study are discussed. Lastly, the implications of the findings for social work practice are outlined and a recommended flow chart for identifying child victims of trafficking is presented.

CHILD TRAFFICKING IN SOUTH AFRICA

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2013), "human trafficking is a global problem and one of the world's most shameful crimes, affecting the lives of millions of people around the world and robbing them of their dignity". Many countries in the world are affected by human trafficking, whether or not they are party to the UN Trafficking Protocol. Almost every country is impacted on by trafficking either as a country of origin, country of transit, and/or as the country of destination. To illustrate this further, UNODC (2013) reports that victims from at least 127 countries were exploited in 137 countries. These 137 countries were not the victims' countries of origin, but were either countries of transit and/or destination, thus indicating the prevalence of transnational trafficking.

Although statistics regarding trafficking of children are unreliable, it is generally understood and widely reported that trafficking patterns in Africa run from north of Africa to the south, with countries in Central, East and West Africa being referred to as countries of origin, whereas the ones in the South are regarded as transit or destination countries. According to the United States Trafficking in Persons (US TIP) Report (2013) and UNICEF (2003), South Africa was reported as being a country of origin, transit and destination. South Africa, though placed on Tier 2 of the US TIP Report (2013) for the third year in a row, recently introduced a comprehensive legislation that addresses human trafficking as a measure to counter the growing trends of trafficking. According to the 2013 US TIP report, the South African government does not fully comply with minimum standards, but it is making significant efforts to bring itself into compliance with these standards, which include prevention, prosecution and protection.

The exact number of children trafficked within, out of and into South Africa is unknown. Further research by Gallinetti (2008) and Allais, Combrink, Connors, Van Rensburg, Ncoyini, Sithole and Wentzel (2010) failed to produce any comprehensive insights into and statistics on trafficking. However, that does not mean that South African children are not trafficked and/or that children are not trafficked into South Africa. According to the Lexis Nexis's Human Trafficking Awareness Index (2013), media articles across Africa report that 54.5% of trafficked victims in Africa are children. In South Africa non-governmental organisations (NGOs) reported that 60% of trafficking victims are children (US TIP Report, 2010, 2012).

Research on human trafficking in South Africa has been primarily carried out by UNICEF (2003), Martens, Pieczkowski and Van Vuuren-Smyth (2003), Allais et al. (2010) and Molo Songololo (2000, 2003). The findings from these studies report that South Africa is a country of origin, transit and destination, and that the child victims are of both genders, with a majority being trafficked to South Africa for sexual and labour exploitation. The studies acknowledge that half of the child victims had been abducted, whereas the rest were recruited with false promises of employment, marriage and education. This shows that socio-economic dynamics also play a big role in the vulnerability of trafficked children (De Lange, 2007; Dottridge, 2004; Sawadogo, 2012, United Nations Education and Scientific Organisation (UNESCO), 2007) as well as re-trafficked children (Brunovskis & Surtees, 2012; Jobe, 2010).

Kamidi (2007) and Sigfridsson (2012) researched general aspects of child trafficking, whereas Van der Watt and Ovens (2012) studied the practice of ukutwala, i.e. forced marriages. Recently, Allais (2013) argued that trafficking of boys and men is under-researched in South Africa. Researchers who have looked at sexual exploitation in the context of trafficking in South Africa include Hilton (2007), Kennedy (2010), Kropiwnicki (2012), Kruger and Oosthuizen (2012) and Lutya (2010). Limited research on the identification of child victims of transnational trafficking is a cause for concern, because presumed cases of child trafficking continue to be identified in South Africa.

IDENTIFICATION OF CHILD VICTIMS OF TRAFFICKING

According to Herman (cited in Bhana & Hochfeld, 2001), continuous trauma in childhood has the potential to form and deform a child's emerging personality. In spite of the resource-scarce environments that some of the child victims come from, trafficking further robs children of the psychological, spiritual, cultural and social development which they would have otherwise somewhat enjoyed had it not been for the exploitation. In addition, the children experience neglect as well as physical, psycho-emotional and sexual abuse, and are deprived of satisfying typical developmental needs for education, care, affection and safety. Recurring trauma, because of the exploitative trafficking experiences, can manifest in various ways, although its presentation is influenced by the child's age, available support structures and their stage of development (Bhana & Hochfeld, 2001). International studies by Bjerkan and Dyrlid (2006), UNICEF (2003) and Zimmerman, Hossain, Yun, Roche, Morison and Watts (2006) acknowledge that the severity and range of symptoms exhibited by trafficked persons, including children, usually indicates the importance of intervening rapidly and holistically.

Child victims of trafficking are invisible, because the exploitation they encounter when they are in the trafficking situation is not always visible, since traffickers use legitimate fronts to cover up their illegal actions. In child trafficking victim identification has been reported as a serious issue facing counter-trafficking agencies worldwide (Bump & Duncan, 2003; Gozdziak & MacDonnell, 2007; Oketch et al., 2012; Rafferty, 2008; Rigby, 2011); yet identification is the "institutional process that allows the potential victims of trafficking and related violence to obtain access to programmes of assistance and protection" (Aradau, 2004:43). Indeed, without correctly identifying child victims of trafficking and referring them timeously, it is almost impossible to contemplate developing and providing the necessary assistance that they require. Identification, referral and assistance provision go hand in hand. According to Aradau (2004:42), "without the identification of victims, the whole issue of assistance and protection becomes superfluous".

According to the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (2011:16), identification of victims is usually based on the definition of trafficking as stated in the country's trafficking legislation. The 2011 OSCE research report acknowledges that "various actors involved in victim identification have different agendas and tend to interpret the definition differently". However, according to Bump and Duncan (2003:208), the first contact with unidentified child victims of transnational trafficking is likely to be made by immigration officials at the port of entry or detention facility, the police or social services/medical service providers.

Research by Lange (2011) indicates that self-identification through hotline numbers has not produced the same high positive results in comparison to domestic violence and child abuse cases. Previous research by Clawson, Dutch, Solomon and Grace (2009) and the Polaris Project (2012) report that victims of transnational trafficking are usually not aware that they are victims, thus self-identification becomes a challenge. Wirtz (2009) also reports that victims of trafficking might have experienced various kinds of labour exploitation before being trafficked and therefore they might not think that trafficking-related exploitation is unusual, illegal or abusive. Nonetheless, it has been suggested in the US TIP Report (2013) that victims of trafficking, whether domestic or transnational, should be involved in the process of identification whenever possible. Generally, it is essential that the victim's participation in or during identification is not to the detriment of the victim's psychosocial well-being, but that it is an empowering process which contributes towards safeguarding disclosure of trafficking experiences.

After escaping from a trafficking situation, the severity and range of symptoms exhibited by the child usually indicates the importance of intervening rapidly. Initial assistance during the "golden hour", or what might also be referred to as crisis intervention care, includes assessment and identification of trafficking, emergency medical assistance, making available resources that meet the child's basic needs (such as security, rest, food), and specialised psychosocial support. Victim identification is thus crucial to the successful provision of these services by social workers and other service providers. However, the appropriate referral of victims is just as important as identification and assistance provision. Without proper identification, referral cannot happen, and without referral, timeous assistance cannot be given to the victim. Therefore, all these stages are connected and they form crucial inter-links in the protection of child victims of trafficking.

According to the South African Trafficking Act (2013) and the Children's Act (2007), irrespective of a trafficking experience, if a South African or foreign-born child presents as being in need of care and protection, they should be referred to social services. The process for reporting and the referral of victims is different for children and for adults, as outlined in the Trafficking Act (2013). The obligation to report presumed cases of child trafficking applies to any person with a reasonable suspicion. This mandatory reporting gives the population a sense that something is being done about the issue, and that they can be part of the process. Thus, community policing is significant towards combating trafficking, since the community's intelligence can be harnessed and applied timeously to protect victims of trafficking.

Palmer (2010) researched the essential role that social work plays in addressing the needs of victims and survivors of trafficking. A study conducted in South Africa by Sambo and Spies (2012) looked at the role of the social worker in the prevention of child trafficking at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Limited research on the identification of child victims of trafficking in South Africa is a cause for concern, because the South African Trafficking Act (2013) calls upon social workers to respond to, and provide support and assistance to, this vulnerable population. In the light of the above discussions, the following two research questions formulated: who identifies child victims of trafficking, and what steps should be followed in this process?

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was applied as it promised to give deeper meaning to, and provide richer details of, the lived experiences of trafficked children (Fouche & Schurink, 2011). A narrative research design was used because the researcher was concerned with, and wanted to explore, the experiences of the trafficked children and key informants (Czarniawska, 2004). Purposive sampling was applied and the basic criteria for selecting the child participants were non-South African trafficked children exploited for any purpose, any gender, between ages 10 and 17 years when rescued in South Africa, and accommodated at government-registered places of safety. Ten former trafficked children were interviewed with a view to making the study child-centred (Wirtz, 2009). Data triangulation was used to enhance the credibility, confirmability and dependability of the study (Shenton, 2004; Weyers, Strydom & Huisamen, 2008). Interviews were conducted with 22 key informants, including social workers, child protection officers, researchers, victim empowerment practitioners, a detective and a human rights lawyer. The selection criteria for the key informants were that they should be available during data collection, and should have been working in the child protection field for at least six months prior to data collection. In addition, the social workers had to be registered with the South African Council for Social Service Professions (SACSSP).

Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time and data that would have been collected from them would be destroyed and not used for the study. Informed consent and assent were obtained, anonymity and confidentiality ensured, and debriefing sessions were made available. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Johannesburg (Strydom, 2011). All interviews were audio and digitally recorded with the participants' consent. All data collected were analysed using thematic analysis as illustrated in Table 1.

INTEGRATED DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

Identification of child victims of trafficking can be equated to lifting veils of silence because the trafficked children are no longer hidden, but they become visible and they can be heard. Findings from the study participants indicate that child victims of trafficking were mainly identified by community members, the police or through self-identification.

Self-identification of child victims of trafficking

Self-identification was one of the ways that the child victims of trafficking escaped from the trafficking situation. If awareness-raising efforts do not reach victims of trafficking in their countries of origin, self-identification in a country of transit or destination rarely occurs. This becomes a major challenge with self-identification as victims are not aware of the trafficking indicators and therefore they do not suspect when anything is amiss. The lack of information makes victims gullible and more vulnerable to exploitation and it prolongs their stay within a trafficking situation. The majority of the key informants interviewed acknowledged that lack of knowledge and awareness of self-identification are a key challenge when it comes to identification of victims of trafficking. This is illustrated in the following extract:

"...there are a lot of community organizations that pick these. There's one in inner city Jo 'burg ... They pick up a lot of children through their outreach work and once they talk to those children and even their mothers, they find that they've actually been trafficked but they [victims]don't [know]. The women and children, they don't know so that they can distinguish [for] themselves that that's what happened to them. They just know that they have been deceived." (Stakeholder 1)

The interview extract shows that self-identification is rare. It is rare because unless someone more knowledgeable in trafficking, its indicators and consequences comes along, identification and subsequent rescue might not take place. This finding supports Clawson et al. (2009) and the Polaris Project (2012) research findings that victims of trafficking are usually not aware that they are victims. This study further supports Pearce, Hynes and Bovarnick's (2009) findings when they interviewed practitioners, who concurred that children would not use the term "trafficking" to describe their experiences because it does not resonate with them and those exploitative experiences. What they could fathom was that they could not withstand the abuse anymore and they yearned for similar developmental goals like other children their age. True to that, the children interviewed for this study escaped from the trafficking situation, not because they knew they had been trafficked, but because they felt tricked, cheated and also because they could not take the abuse and exploitation any longer. This is further illustrated in the extract below:

"I ran away ... because I felt it was too much. I suffered a lot ... I was wandering around the streets, so the community called the police and said there is this child and then they [police] took me to [name of place of safety]." (Siphiwe, a Mozambican trafficked youth)

The children interviewed reported elements of hurt, suffering and abuse, and mistrust. The researcher did not go into details of the abuse and exploitation, but by reflecting with them on the referral and service provision interventions undertaken, it was evident that part of escaping from the trafficking situation was so that they did not have to deal with the pain and hurt any longer. Thus, it is crucial that service providers be sensitised to trafficked children's possible prior experiences in the hands of the trafficker (Rigby, 2010).

All the children who had escaped and were interviewed for the study reported that they knew it was dangerous to be on the streets alone. This was an interesting finding, because most literature on trafficked children begging on the streets have been linked to traffickers exploiting them in this way (End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT), 2010; Segawa, 2013; Wenke, 2013), yet this study was able to establish that some children end up on the streets after escaping from a trafficking situation. A point of contradiction that the authors want to put forward is that when children are being exploited through begging, the trafficker offers some sort of illusionary protection. However, after they escape from the trafficker and they are on their own in the streets, fearful, with no access or knowledge of where to seek assistance, they are open to further exploitation by potential abusers who notice their vulnerability. However, that is not to say that being in a trafficking situation is better and safer than being alone on the streets. Neither choice is safe for children, because exploitation will happen in either of the cases, subsequently compromising the child's development and wellbeing (Human Rights Watch (HRW), 2010).

Identification by community members

In this study community members were highly significant in counter-trafficking efforts as they were able to identify and refer the most child victims of trafficking for further assistance. The community and its members lived within certain geographical boundaries, which increased their visibility and they subsequently ended up being the largest single source of intelligence and information. Another possible explanation for this is that community members tend to be more familiar with their surroundings and they are able to observe changes taking place within their environment, as reported in the case below:

"There' s a case going on in Benoni. Those children are from Lesotho. They are brothers under 15. They came here with their uncle, for them to come and herd cows and livestock. They don' t go to school. They literally stay next to the kraal. They are actually staying with the livestock in a very small shady shack and the uncle is staying in this plush house, his children are going to school, after school they come to supervise these [trafficked] ones then they go back home. These children were rescued by one of our partners and when they were interviewed how they actually got there, they came here, they crossed the border without papers. They were asked to lie down. I don't know what was put on top of them when the car was crossing the border and that on its own is human trafficking but I don' t think he [children' s uncle] knows that that is human trafficking... " (Stakeholder 5)

The study's field notes indicate that community members were generally suspicious of their non-South African neighbours and these suspicions grew with the sudden appearance and/or disappearance of foreign children being housed by the neighbours. The children were being over-worked in the house and made to engage in lengthy activities which were not child friendly, and some were not attending school even during school term. In other instances, community members noticed vulnerable children who had just arrived on the streets and were not hard-core street children. Because of their concern, the community members became inquisitive and talked to the children about what led to their current situation. Interestingly enough, these children were the trafficked children who had run away from unbearable exploitative trafficking contexts and were now on the streets. Through the intervention of community members, both sets of children i.e. those exploited in private homes and the new arrivals on the streets, were subsequently referred to the social worker or police depending on the proximity of either office. The interview extract below shows that effective community relationships can have meaningful results within the sphere of child protection.

"...so the police found him, then the social worker brought him here. He's saying that one of the ladies [community members] who took him from the streets, they took him to the police station, then from the police to the social workers and then brought here... " (Sibusiso, a Mozambican trafficked child, through an interpreter)

In another incident narrated by a social worker, several community members noted the suspicious activity that was happening within their community. These concerns were then reported to social workers at a designated child protection organisation, who then alerted the police. The nature of trafficking, the required criminal justice intervention, the necessary child protection measures and the sensitive investigation by the police warranted the trafficking process to be disrupted, as indicated in the quotation below.

" In one case when the children, the girl child landed with us, there was good cooperation from community people. We informed the police and just before the flight was leaving for London from OR Tambo airport, the immigration people and the police moved in to stop the flight and they arrested this person [trafficker] and the child was placed with us [a place of safety]." (Social worker 7)

As shown in the extract, the contribution that community members have made in South Africa towards identification of victims and subsequent arrest of traffickers is positive. The information brought forward by community members through community policing has led to more children being protected. It is evident that the principles underpinning community policing, which influenced positive identification of victims, is based on strong reliance on well-built and negotiated community relations between the police, the social workers and the community. The ripple effect of this is that these community members are then more likely to call on the police or the social worker again and come forward with information in future (OSCE, 2011; Protection Project, 2012). In the light of the above, it is quite clear that identification by a social worker or the police might not always happen in most areas in South Africa, because of their low ratio to the high population being served. Therefore, it becomes essential to empower community members and to educate them on trafficking, its prevalence, potential indicators, rights of victims and available resources for reporting cases.

Identification of victims by police officers

Policing includes a wide array of activities such as investigating and preventing crimes, and in this study it included child protection through identification of child victims of trafficking. As evidenced by this study, the police have a great possibility of identifying child victims of trafficking through referrals by community members or through normal routine police operations. The children interviewed reported that when they were rescued by the police, the police happened to be at the point of rescue because the police were carrying out their normal routine operations. This was corroborated by social workers interviewed, as depicted in the following extract:

" Most of the children who are trafficked are brought to the centre by the police ... the police just find them on the streets and as a result, because they don' t want to see any child on the streets, they end up bringing them to the centre... " (Social worker 1)

The police were reported in the previous interview extract as trying to maintain order through the removal of prostitutes, criminals, and children living and working on the streets. However, during these routine operations it seems they come across vulnerable trafficked children. This finding seems to be consistent with and supports OSCE's (2011) report that police gain information about trafficking by controlling what they consider to be problematic areas, especially during patrolling. This indicates that identification can also be informed by police investigations of other crimes, which are either directly or indirectly linked to trafficking such as domestic violence, prostitution, kidnapping and drug trafficking. In this study the children found during the police routine operations were presumed to be victims of trafficking. With further interaction, the police were able to ascertain the status of the children by asking questions that assisted them to make a decision as to whether the crime of child trafficking was being committed and to establish the child's identity as a victim of trafficking.

In this study victim identification by the police did not take place at the location of exploitation or where the child was found. Prior to the police starting to interrogate the children who were interviewed for this research, it was evident that they assessed the immediate needs of the children and in certain instances either sent the children for medical care, psychosocial support or provided them with something to eat first. This study has been able to demonstrate that the children were clearly treated with respect, as their physiological needs were attended to first. The police then subsequently asked questions related to personal information, recruitment, transportation and exploitation. During data collection there were similar responses from the children interviewed on the type of questions asked by the police, such as biographical information, trafficker details and the potential trafficking indicators, which included trafficking routes and the experiences of abuse. In addition to this, the key informants reported that the child's behaviours were also being observed to establish congruency with the story being narrated or for signs of emotional instability and discomfort. The following brief extract is that of a child who was trafficked by her father when she was asked about the interview with the police:

"... like where's my father, how comes I'm living here and all those questions... " (Siphiwe, a Mozambican trafficked youth)

According to the South African Police Service (SAPS) National Instructions on Victim Empowerment (forthcoming), the comprehensive report based on this first contact has to be passed on to the investigating officer, after a case has been opened at the police station. There is an assumption that this did not happen. It is difficult to explain this result, but it might be related to the fact that from the research interviews it was evident that no police officer contacted the children once they had been placed in alternative care.

Evidently, all the children interviewed were not informed by the police why they were being questioned and neither were they told what will happen with that information or what it will be used for. This contravenes the UN Recommended Guidelines (2002) that govern processing of collected personal information from trafficked persons, including children. However, on the other hand, age and lack of knowledge might have impacted on the information sharing by the police, as it was noted that probing for details from presumed victims of trafficking has the potential to be abusive to the children, if they are not ready to discuss what happened. Nevertheless, as argued by Pearce (2011:18), "good practice helps the child understand their experience of abuse while alleviating any sense of responsibility". In this study it was evident that a majority of the children had high stress levels which did not make them much concerned about what was going on, or whether or not to trust the police person, but rather they longed and yearned for a safe place to stay and for their immediate needs to be met. In response to the question whether she would have wanted to know why the police were asking her many questions, a participant said:

"Nooooo I was too young to think about that ... I was thinking, hey if these people can get me to a safe place to stay that will be fine with me, so that I can continue studying, that will be ok ... " (Siphiwe, a Mozambican trafficked youth)

Children's views of the police as safeguarding them from further harm were quite different from those depicted by the key informants in the study, who alleged that the police were corrupt, incompetent, lax and were involved with trafficking syndicates. This is supported by the extract below:

"... we do come across allegations of police corruption and police inactivity that compromise the ability to, say if we can report of maybe child prostitution the police will go, they'll do a raid, everybody will be taken to the police station, released and in a couple of days, everybody's back where they were and there seems to be no in-depth investigations of where these people come from, how did they get there, and what kind of intervention definitely prevents us from helping those children effectively and dealing with the issue that they may actually have been trafficked ..." (Key stakeholder 7)

It is important to bear in mind the possible bias in the children's and the adult's responses. However, an analysis of these allegations points to the child victims' rights being violated by the trafficker and subsequently there is further violation and secondary victimisation by the child protection and criminal justice systems that are meant to protect the children. In addition, it defeats the purpose of creating effective prevention measures through information shared by the trafficked victims.

Identification of victims by social workers

Social workers in direct and indirect practice can play key roles in the identification of trafficked children. This was acknowledged by the key informants interviewed, but interviews with children indicate otherwise. Only one child participant, as shown in the extract below, was identified by the social worker:

" Social worker find me and bring me here." (Maradona, a Mozambican trafficked child)

The results of this study showed that social workers identified few cases of child trafficking. The reason for this is not clear, but it may be linked with the scarcity of social workers on the ground. This is a cause for concern, because social work is heavily tasked with identifying and assisting child victims of trafficking. However, irrespective of who identified trafficked children in this study, social workers provided a key link during assessments, referral and service provision. All the children interviewed had an opportunity to meet with a social worker, at least once. The registered social worker was able to do an initial assessment of the presumed or identified trafficked child and ascertain his or her psychosocial needs and circumstances. On the basis of the available evidence, the social workers concerns about the child's safety, wellbeing and presumed trafficking were established. It can be correctly assumed that the children interviewed had undergone statutory intervention, as they were being accommodated in registered places of safety, according to Sec. 155 6(b)(v) of the South African Children's Act.

Identification by social workers is directly linked to social work assessments. When the social workers who were interviewed in the study were asked how children end up in their care, there was a variety of responses. The common responses involved engaging with the child and finding out their background information and how they ended up in and out of the trafficking situation. The first extract below shows how the social worker applied an inquisitorial approach to determine if the trafficked child is in need of care and child protection:

" You would find that with children who are trafficked, there is always a push and pull factor and we would look at that. An assessment is done on the circumstances of the child and we would look at what is the most presenting problem ... and often the child is placed in alternative care. And that is how we render the services to the child and then ensure that the child is not exposed to those circumstances again. " (Social worker 2)

The practical approach that social workers use, which was also highlighted in this study, is that once information is collected from the child victims, it is essential that it translates into action. Although the social workers reported that assessment and report writing for statutory work was routine, there may be complexities depending on the merits of the case, which may be influenced by the scarcity of resources in South Africa. This is illustrated in the extract below:

"... the social worker will first take action. All the child protection options are available in South Africa . to end that exploitation. So that child can be placed in temporary safe care, depending on the circumstances of the child. The social worker might feel that the child needs to go into temporary safe care and I think in almost all those cases, all cases of suspected trafficking, those children will be taken to the Children' s Court as children in need of care and protection. Because in every single case a social worker would have to do an investigation to assess the situation of the child, the nature of the exploitation and take a decision as to the most appropriate care of that child in future. " (Social worker 5)

The two previous extracts above and the next one all denote the essential role a social worker plays during needs assessment. The one below indicates how children can be involved in decision-making processes. It acknowledges the importance of the victim's participation and calls for social workers to listen to the children, because they are best placed to provide information and they know their needs better. This study confirms that good mental health is associated with participation. These findings further support the idea of child participation. This is illustrated by the following interview extract:

" It' s the social worker who does the identification, because they admit the children and collect background information about the reason they are in the centre and just to check who brought them and why and what happened ... We learn from them. They are the ones who give us information about what they think we can do. We call them teachers [laughter] because they know much. They know their problems much more than us ..." (Social worker 1)

The three quotations are from three different social workers who were interviewed and if one is not knowledgeable or skilled enough in conducting assessments, one could erroneously identify fragmentation in how assessments for identification purposes are conducted by the social workers. Nevertheless, none of the approaches and modes of assessment applied is incorrect in their orientation. However, it may further be argued that each approach can be applied to a specific child-trafficking situation (Child Exploitation and Online Protection (CEOP), 2009). The authors would recommend that a combination of the approaches be applied in assessing child trafficking cases; but what really matters is that assessments are facilitated in a comprehensive manner that ensures accuracy, accountability and victim's participation (CEOP, 2009; Pearce et al., 2009). This finding has important implications for developing initial assessments which minimises harm and provides baseline information and guidance to social workers on child protection services needed by the child. Reduction of further harm during identification is shown in the extract below whereby the police-social worker collaboration is encouraged:

" Some of them [social workers] are very intelligent, very good intelligence gatherers for us [police] because we' ve actually communicated with social workers and say, when you conduct an interview, you' ll obviously have a lot of questions, but I would like you to slip this through when you' re asking about that. When you' re asking about that, you can ask them about this. When you' re asking about how you came to South Africa, just put in these two questions there. We would like to know the answers to these two, that's what it is about. " (Stakeholder 13)

IMPLICATION FOR SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

There are no formal, clear and accessible procedures for identifying child victims of trafficking in South Africa. In the light of the above findings, identification of a child who has been trafficked transnationally is a process and not a mere event. Thus fragmentations during identification can be better understood from that angle and also based on the notion that trafficking does not have a clear identifiable beginning, middle and ending, but rather the victim's stories are reconstructed according to how the victim narrates them.

The key people identified as being instrumental in the identification of trafficked children include the victims themselves, community members, police officers and social workers. This adds to the point that there is no wrong door or single point of entry for a trafficked child, but rather that wherever a child first interacts with a service provider or concerned community member, the child can be connected to a broad range of child protection services.

During identification social workers, other service providers and the community members providing assistance need to respect the voice of the child, whilst also upholding the best determination principle of protecting children and keeping them safe from harm and further abuse and exploitation. Furthermore, the informal identification of trafficked children by community members illustrates that the children's identification process needs to respond to local trafficking trends and patterns and that the protection of children, even against trafficking, is a collective process requiring collective responsibility (Emser, 2013; Protection Project, 2012; Wessels & Edgerton, 2008). These informal and undocumented referral mechanisms in South Africa for child victims of transnational trafficking need to be improved and better co-ordinated to ensure greater protection for children. Indeed, referral of trafficked children is not purely just about transferring the child from one service provider to the next, but it is a fundamental mechanism that ensures social workers provide integrated and holistic care to trafficked children. Furthermore, it was evident from the study that establishing cooperation mechanisms with various service providers and community members is valuable in the referral and subsequent social work assistance provision for trafficked children.

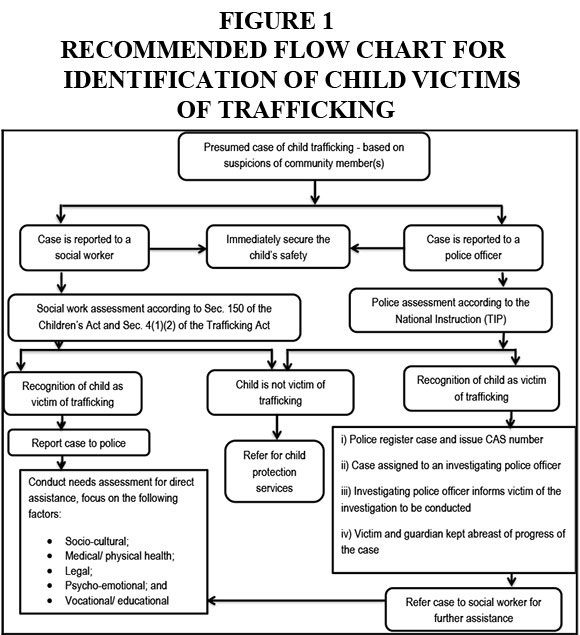

Proper and rapid identification of trafficked children in South Africa needs to be prioritised so that there is uniformity in the identification of presumed cases of trafficking. This is because lack of awareness or the application of uneven protocols leads to the development of walls of silence, which perpetuates children's exploitation. These walls need to be broken down and the following flow chart (Figure 1) suggests the identification process that could be followed:

The flow chart can be further adjusted to include identification by other service providers. It was also noted that because victims of trafficking are better at identifying other victims and target areas, social workers and other service providers should involve them in their victim-identification endeavours.

The identification of trafficked victims is not an event but a process that is highly dependent on the child's port of entry and the ever-changing trafficking trends and patterns, and thus training of service providers, especially the police and social workers, should incorporate these ideas. Without the bridge provided by the community members (See Fig. 1), it will be challenging for social workers to reach some victims of child trafficking. Thus, social workers can play a primary preventative role of facilitating regular awareness-raising campaigns and trafficking training for community members as a way of developing sustainable child-protection systems in South Africa. The benefits from these community-based child protection systems can be threefold, i.e. subsequently increase the children's network and circle of care, integration of local trends and patterns of child trafficking into case management, and acting as a link to the national child-protection system.

Rigby (2011:333) concludes that "traumatized young people may not come out with beautiful precise, matching sets of information". The combination of findings from the study provides some support for the conceptual premise that ultimately it is about recognising that every child has a story and a voice that needs to be evoked and that their participation in the identification-assessment process is vital. One of the issues that clearly emerges from this article is that identification of child victims of trafficking is not simple clear-cut process, although it is one way to ensure that the presumed trafficked child will receive appropriate care, support and protection.

REFERENCES

ALLAIS, C. 2013. The profile less considered: the trafficking of men in South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 44(1):40-54. [ Links ]

ALLAIS, C., COMBRINK, H., CONNORS, D., VAN RENSBURG, J.M., NCOYINI, V., SITHOLE, P. & WENTZEL, M. 2010. The Tsireledzani Report: understanding the dimensions of human trafficking in Southern Africa. A research commissioned by the NPA from the Democracy and Governance Programme of the Human Science Research Council (HSRC). [ Links ]

ARADAU, C. 2004. The perverse politics of four letter words: risk and pity in the securitization of human trafficking. Journal of International Studies, 33(2):251-277. [ Links ]

BHANA, K. & HOCHFELD, T. 2001. Now we have nothing: exploring the impact of maternal imprisonment on children whose mothers killed an abusive partner. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR). [ Links ]

BJERKAN, L. & DYRLID, L. 2006. The silenced experience: reintegration of victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation. Oslo: Fafo Institute. [ Links ]

BRAUN, V. & CLARKE, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

BRONFENBRENNER, U. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In: GAUVAIN, M. & COLE, M. (eds), Readings on the development of children (2nd ed). New York: Freeman. [ Links ]

BRUNOVSKIS, A. & SURTEES, R. 2012. A fuller picture: addressing trafficking-related assistance needs and socio-economic vulnerabilities. The Fafo/NEXUS Institute Project: improving services to trafficked persons. Norway: Fafo/NEXUS Institute. [ Links ]

BUMP, N.M. & DUNCAN, J. 2003. Conference on identifying and serving child victims of trafficking. International Migration, 41(5):201-218. [ Links ]

CEOP. 2009. Strategic threat assessment: child trafficking in the UK, London. [Online] Available: www.ceop.gov.uk. [Accessed: 11/10/2011]. [ Links ]

CLAWSON, H.J., DUTCH, M.N., SOLOMON, A. & GRACE, L.G. 2009. Study of HHS programs serving human trafficking victims. Final report. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [Online] Available: http://aspc.hhs.gov/hsp/07/humantraffícking/fínal/index.pdf. [Accessed: 10/10/2012]. [ Links ]

CZARNIAWSKA, B. 2004. The use of narrative in social science research. In:HARDY, M. & BRYMAN, A. (eds), Handbook of data analysis. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DE LANGE, A. 2007. Child labour migration and trafficking in rural Burkina Faso. International Migration, 45(2):147-167. [ Links ]

DOTTRIDGE, M. 2004. Kids as commodities: child trafficking and what to do about it. Lausanne: Terres des Hommes. [ Links ]

ECPAT. 2010. ECPAT UK Briefing. Child trafficking: begging and organized crime. [Online] Available: www.ecpat.org.uk/sites/default/files/begging_organized_crime_briefing.pdf. [Accessed: 12/06/2013]. [ Links ]

FARRELL, A., McDEVITT, J. & FALY, S. 2010. Where are all the victims? Understanding the determinants of official identification of human trafficking incidents. Criminology and Public Policy, 9(2):201-233. [ Links ]

FONG, R. & CARDOSO, B.J. 2010. Child human trafficking victims: challenges for the child welfare system. Evaluation and Programme Planning, 33(3):311-316. [ Links ]

FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grassroots: for the social service professions (4th ed). Cape Town: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

FRIEDMAN, B.D. & ALLEN, K.N. 2010. Systems theory. In: BRANDELL, P.J.R. (ed.), Theory and practice in clinical social work. LA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GALLINETTI, J. 2008. Child trafficking in SADC countries: the need for a regional response. Harare: ILO. [ Links ]

GOZDZIAK, M.E. & MacDONNELL, M. 2007. Closing the gaps: the need to improve identification and services to child victims of trafficking. Human Organization, 66(2):171-184. [ Links ]

GOZDZIAK, M.E. 2010. Identifying child victims of trafficking: towards solutions and resolutions. Criminology and Public Policy, 9(2):245-255. [ Links ]

HEPBURN, S. & SIMON, J.R. 2010. Hidden in plain sight: human trafficking in the US. Gender Issues, 27:1-26. [Online] Available: http://www.Springerlink.com/content/v166u62402361374/fulltext.pdf. [Accessed: 10/10/2012]. [ Links ]

HILTON, L. 2007. Contemporary slavery: sex trafficking in South Africa and suggested solutions. [Online] Available: http://www.africanstudies.uct.ac.za/postamble/vol3-1/slavery.pdf. [Accessed: 12/11/2008]. [ Links ]

HOPPER, E.K. 2004. Under-identification of human trafficking victims in the US. Journal of Social Work Research and Evaluation, 50(2): 125-136. [ Links ]

HRW. 2010. Off the backs of the children: forced begging and other abuses against Talibes in Senegal. New York: HRW. [ Links ]

JOBE, A. 2010. The causes and consequences of re-trafficking: evidence from the IOM human trafficking database. Geneva: IOM. [ Links ]

KAMIDI, R. 2007. A legal response to child trafficking in Africa: a case study of South Africa and Benin. Bellville, South Africa: University of Western Cape. (Unpublished Master's Dissertation) [ Links ]

KENNEDY, L.J. 2010. Shrouded sins: an exploration of child sex trafficking in South Africa. Pell Scholars & Seminal Theses. Paper 43. [Online] Available: http://escholar.salve.edu/pell//_theses/43. [Accessed: 30/10/2011]. [ Links ]

KROPIWNICKI, Z.D. 2012. The politics of child prostitution in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 30(2):235-265. [ Links ]

KRUGER, H.B. & OOSTHUIZEN, H. 2012. South Africa - safe haven for human traffickers? Employing the arsenal of existing law to combat human trafficking. PEL Journal, 15(1):283-343. [ Links ]

LANGE, A. 2011. Research note: challenges of identifying female trafficking victims using a national 1-8000 call center. Trends in Organized Crime, 14(1):47-55. [ Links ]

LEXIS NEXIS. 2013. Human Trafficking Index. South Africa. [Online] Available: www.lexixnexis.co.za/ruleoflaw. [ Links ]

LOFF, B. & SANGERA, J. 2004. Distortion and difficulties in data for trafficking. The Lancet, 363(9408):566. [ Links ]

LUTYA, M.T. 2010. Lifestyles and routine activities of South African teenagers at risk of being trafficked for involuntary prostitution. Journal of Child and Adolescents Mental Health, 22(2):91-110. [ Links ]

MARTENS, J., PIECZKOWSKI, M. & VAN VUUREN-SMYTH, B. 2003. Seduction, sale and slavery: trafficking in women and children for sexual exploitation. Pretoria: IOM. [ Links ]

MOLO SONGOLOLO. 2000. The trafficking of children for purpose of sexual exploitation - South Africa. Molo Songololo. [ Links ]

MOLO SONGOLOLO. 2003. Trafficking of women into the South African sex industry. Molo Songololo. [ Links ]

OKETCH, D., MORREAU, W. & BENSON, K. 2012. Human trafficking: Improving victim identification and service provision. International Social Work, 55(4):488-503. [ Links ]

OSCE. 2011. Trafficking in human beings: Identification of potential and presumed victims. A community policing approach. SPMU Publication Series, Vol. 10. Vienna. [ Links ]

PALMER, N. 2010. Essential role of social work in addressing victims and survivors of trafficking. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law, 17(1):43-56. [ Links ]

PEARCE, J.J. 2009. Young people and sexual exploitation: it's not hidden, you just aren't looking. Routledge: Cornwall. [ Links ]

PEARCE, J.J., HYNES, P. & BOVARNICK, S. 2009. Breaking the walls of silence: practitioners response to trafficked children and young people. NSPCC. [Online] Available: www.nspcc.org.uk/inform/research/findings/breaking_the_wall_of_silence_report_wdf66135.pdf. [Accessed: 10/10/2011]. [ Links ]

POLARIS PROJECT: FOR A WORLD WITHOUT SLAVERY. n.d. Human Trafficking FAQs. [Online] Available: http://www.polarisproject.org. [Accessed: 12/11/2012]. [ Links ]

PROTECTION PROJECT, THE. 2012. 100 Best practices in combating trafficking in persons: the role of civil society, 1. Johns Hopkins University - Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. [Online] Available: www.protectionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/100-best-practices-in-combating-TIP-Final-Doc1.pdf. [Accessed: 12/06/2013]. [ Links ]

RAFFERTY, Y. 2008. The impact of trafficking on children: psychological and social policy perspectives. Child Developmental Perspectives, 2(1):13-18. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2005. Children's Act, Act No. 38 of 2005. [ Links ]

Government Gazette. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Publishers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2013. The Prevention and Combating Trafficking in Persons Act 7 of 2013. Government Gazette. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Printers. [ Links ]

RIGBY, P. & WHYTE, B. 2013. Children's narratives within a multi-centred, dynamic ecological framework of assessment and planning for child trafficking. British Journal of Social Work, 43(5):1-18. [ Links ]

RIGBY, P. 2011. Separated and trafficked children: the challenges for child protection professionals. Child Abuse Review, 20:324-340. [ Links ]

SAMBO, J.P. & SPIES, G. 2012. The role of the social worker in the prevention of child trafficking in South Africa. Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 48(2): 113-131. [ Links ]

SAWADOGO, W.R. 2012. The challenges of transnational human trafficking in West Africa. African Studies Quarterly, 13(1&2):95-115. [ Links ]

SEGAWA, N. 2013. Kids trafficked from villages to beg in Kampala. [Online] Available: www.chimreports.com/index.php/new9274-kids-trafficked-from-villages-to-beg-in-kampala.html. [Accessed: 12/06/2013]. [ Links ]

SHENTON, K.A. 2004. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22:63-75. [ Links ]

SIGFRIDSSON, T. 2012. Trafficking of children: the case of South Africa. Stellenbosch, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch. (Unpublished Master's Dissertation) [ Links ]

SIGMON, N.J. 2008. Combating modern day slavery: issues in identifying and assisting victims of trafficking worldwide. Victims and Offenders, 3:245-257. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. 2011. Ethical aspects of research in the social sciences and human service professions. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.L.S. (eds), Research at grassroots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Cape Town: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

UN. 2000. Protocol to prevent, supress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Palermo Protocol). [ Links ]

UN. 2002. The Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking. Report of the UNHCR to the Economic and Social Council. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2007. Human trafficking in South Africa: root causes and recommendations. Policy Paper Poverty Series, 14.5(E). [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2003. Trafficking in human beings, especially women and children in Africa. [Online] Available: http://www.unicef.org/protection/files/insight8e.pdf. [Accessed: 20/05/2008]. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2007. UNICEF calls for increased efforts to prevent child trafficking. [Online] Available: http://www.unicef.org/media/media_40002.html. [Accessed: 14/11/2010]. [ Links ]

UNODC. 2013. Human trafficking: people for sale. [Online] Available: www.unodc.org/toc/en/crimes/human-trafficking.html. [Accessed: 15/10/2013]. [ Links ]

US Trafficking-In-Persons Report. 2010. U.S. State Government Publication. [ Links ]

US Trafficking-In-Persons Report. 2011. U.S. State Government Publication. [ Links ]

US Trafficking-In-Persons Report. 2012. U.S. State Government Publication. [ Links ]

US Trafficking-In-Persons Report. 2013. U.S. State Government Publication. [ Links ]

VAN DER WATT, M. & OVENS, M. 2012. Contextualising the practice of ukuthwala in South Africa. Child Abuse Research: A South African Journal, 13(1): 11-26. [ Links ]

WENKE, D. 2013. Child trafficking for exploitation in begging and criminality: a challenge for law enforcement and child protection. Council of the Baltic Sea States. Child Centre Expert Group for Cooperation on Children at Risk (EGCC). [ Links ]

WESSELS, M. & EDGERTON, A. 2008. What is child protection: concepts and practices to support war-affected children. The Journal of Developmental Processes, 3(2):1-12. [ Links ]

WEYERS, M., STRYDOM, H. & HUISAMEN, A. 2008. Triangulation in social work research: the theory and examples of its practical application. Social Work/ Maatskaplike Werk, 44(2):207-222. [ Links ]

WIRTZ, L. 2009. Hidden children: separated children at risk. London: Children's Society. [ Links ]

ZIMMERMAN, C., HOSSAIN, M., YUN, K., ROCHE, B., MORISON, L. & WATTS, C. 2006. Stolen smiles: a report on the physical and psychological health consequences of women and adolescents trafficked in Europe. London: The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. [Online] Available: http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/genderviolence/. [Accessed: 03/03/2010]. [ Links ]