Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.4 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-4-387

ARTICLES

Social work forensic reports in South African criminal courts: Inevitability in the quest for justice

Mariëtte JoubertI; Carel van WykII

ISocial worker, NICRO Bloemfontein

IIDepartment of Social Work, UFS, Bloemfontein, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Social work forensic reports can play a vital role in sentencing. In this article the expectations of criminal courts of social work forensic reports were established in order to improve the contribution of the social work discipline in the search for justice. An important result indicates that courts would like to make use of social work forensic reports, among others. However, the poor writing style of some of these reports makes them unfit for use in the legal context. It is argued that social workers must be trained in critical thinking and the elements of clear writing to enable them to produce high-quality forensic reports.

INTRODUCTION

Social workers assist court personnel in court cases by means of testifying as professional experts and submitting social work forensic reports. However, forensic report writing is a complex process and requires careful and meticulous attention in order to deliver a written product of outstanding quality.

There is no specific format or guideline for the writing of a forensic report in the field of forensic social work. Consequently, social workers write these reports as they deem fit. A number of guidelines for the writing of a forensic report from the point of view of psychology and psychiatry, however, are available. For instance, the forensic report format proposed by Naudé, Du Preez and Zwiegers (2005:66) for use by psychologists focuses on the presentation of findings of psychometrical tests. Since social workers are not trained in the use of psychometrical tests and have a different focus than psychologists, this report format has no relevance for them. Thus a forensic report format from the social worker's perspective, which focuses specifically on data -collection methods and the reporting of findings from the social work forensic assessment, is required for the social worker doing forensic social work.

Kraftt (2011) notes that public prosecutors seldom make use of social workers' reports as evidence in court cases. However, defence lawyers read these reports to obtain a better understanding of the child's situation and reports are utilised during court procedures only in exceptional instances. On the other hand, Ferreira (2010) would prefer that social work forensic reports be utilised in all cases, while Labuschagne (2010) is of the opinion that there is a high demand for professional social work forensic reports of a higher quality to assist court personnel. The appeal case of Pillay v The State ((739/10) 2011 ZASCA 111) is a point in case. Because of the poorly drafted forensic reports of the social workers, the case went on appeal and the appeal was granted. In the mentioned case (Pillay v The State) it is stated that:

At the time of sentencing in the present case, the trial court had two reports before it, one from a social worker employed by the Department of Social Development and another by a correctional services officer. Insofar as the children are concerned, the report by the social worker can at best be described as sparse. It records that the appellant has six children, aged 18, 16, 12, 11, 8 and 4 respectively. It records that the appellant is currently living with Mbuthuma in a three-bedroom house at Umlazi and that she has a good relationship with him and receives moral support from him. Other than stating that the appellant has six dependent children and setting out the date she had her first child and that the relationship with the father of that child had broken down, nothing further is said about the children. The report by the correctional services officer is two pages long. The only information concerning the children is about the number of the siblings. The sentence imposed by the trial court is set aside and the matter is remitted to the trial court to impose sentence afresh after obtaining the material evidence affecting the children in accordance with what is set out in S v TheState, Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae (CCT 63/10) [2011] ZACC 7 (29 March 2011), M v The State (Centre for Child Law as Amicus Curiae) [2007] ZACC 18; 2007 (2) SACR 539(CC).

The aim of this article is to partially address the above-mentioned shortcomings of social work forensic reports by reporting on the findings of an explorative and descriptive investigation into the writing of these reports. The findings are based on analysis of the expectations of court personnel with regard to social work forensic reports in order to create guidelines for the writing of such reports.

THE SOCIAL WORK FORENSIC REPORT AND LEGAL DISCOURSE

Legal discourse is one of several main discourses in social work. In this discourse the law is seen as positivistic, rational and authoritative (Healy, 2005:35-37). Although the legal discourse is one of the main discourses in social work, and social workers are trained in forensic social work at Master's degree level at the North-West University (NWU), it is not yet recognised as a field of specialisation by the South African Council for Social Service Professions and the title "Forensic Social Worker" may not be used (SACSSP, 2010). While forensic social work is not yet a field of specialisation, many social workers trained in forensic practice make forensic assessments and write social work forensic reports. In order to write social work forensic reports that will be admissible and relevant in a court of law, it is important to understand the interrelationship between criminal law and social work as well as to consider the mentioned characteristics of legal discourse.

Criminal law prescribes how people who have presumably committed an offence must be prosecuted. It is the responsibility of the state to prosecute and punish offenders. Criminal law stipulates the rules regarding the investigation of a suspected offence and the process which should be followed in court (Kleyn & Viljoen, 2002:100). According to Joubert (2010:9), criminal law may be defined as follows:

"The different forms of conduct that are punishable are described by criminal law, which also determines the requirements for each offence crime. As a crime is considered to be committed against society, not against the primary victim only, the State must prosecute and punish the perpetrator. Common-law offences as well as crimes created by statutory law (legislation) form part of criminal law. Criminal Law is practised in the district and regional magistrates' courts, the High Courts, and the Supreme Court of Appeal. The Constitutional Court is the highest court for constitutional matters. The district and regional courts in certain areas also have courts that specialize in, for instance, sexual offences and domestic violence."

Social workers usually provide the District, Regional and High Courts with social work forensic reports, because evidence is not as a rule tendered in the Supreme and Constitutional Courts. They are courts of appeal, and judgement is generally made on the record of the trial court.

The law of evidence determines how the facts of a criminal and/or civil case must be proved. This law is used to determine how witnesses in court must be treated and which evidence is acceptable and which will count as hearsay (Kleyn & Viljoen, 2002:100). Joubert (2010:9) defines the law of evidence as "the rules that regulate the submission of evidence in a court of law. Police officials have to conduct the investigation according to these rules to ensure that the evidence obtained is admissible in court".

The law of evidence is important to the social worker, in particular, as it determines which evidence can be presented to the court when the social worker is called as an expert witness. Therefore, social work forensic reports must be written according to the principles of the law of evidence and the social worker must at all times understand the mandate of the information or evidence required. This pertains to the four stages of the criminal trial, namely pre-trial, main trial, sentence and post-trial. Pre-trial refers to all the proceedings before the plea is finalised. Plea proceedings are followed by the main trial. The burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is on the state. If the version of the accused is reasonably possibly true after all the evidence has been evaluated as a whole, the accused must be acquitted. The main trial consists of the state's case and, after closure thereof, the defence case. Witnesses testify in chief and are then cross-examined. The witness may be re-examined on issues that came to light in cross-examination and have not been dealt with in evidence in chief. Address by the parties follows after closure of the defence case, after which the judgment of the court is delivered. If the accused is convicted, sentencing proceedings commence after judgement. Both parties may adduce evidence on mitigation and/or aggravation. This procedure may also consist of evidence in chief and cross-examination. The court plays an active role in sentencing and may also order evidence to be tendered.

Social workers give opinion evidence, as their evidence is gathered through in-depth social work forensic assessments. According to Schwikkard and Van der Merwe (2002:83), opinion is usually a principle of inadmissibility in courts, as opinion is per se irrelevant. However, the evidence can be admissible based on its relevance, if the expert witness is in a better position than the court to form an opinion and the expert maybe called from time to time to testify in person.

As discussed above, an opinion can sometimes be based on hearsay. Opperman (2012) indicated that the evidence of expert witnesses often contains hear-say evidence, especially if literature and other resources are utilised to strengthen their testimony. Hearsay evidence, according to Kleyn and Viljoen (2002:188), is evidence presented by a person who did not witness the incident herself, but testifies on the grounds of what another person has told her. The Law of Evidence Amendment Act No. 45 of 1988 defines hearsay evidence as "evidence, whether oral or in writing, the probative value of which depends upon the credibility of any person other than the person giving such evidence" (Kruger, 2008:24-40; Schwikkard & Van der Merwe, 2002:22). In general, this type of evidence is not allowed in a court of law, as it is unreliable. However, the court of law is given room to use its discretion to allow hearsay evidence if it is in the interest of justice (Mujuzi, 2013:347). In order for the social work forensic report to adhere to the court personnel's expectations, the social worker needs to illustrate in the report that the information therein will indeed assist the court in making a fair and just decision. Certain law cases can be used to assist the social workers in this regard.

The principles applicable to the admissibility of opinion evidence by experts, including psychologists and social workers, have been set out in numerous authorities. Lawrence and Janse van Rensburg (2006:140) refer to two cases, namely Holtzhauzen v Roodt and Van Zijl v Hoogenhout, where the courts made use of expert witnesses. The Holtzhauzen v Roodt case is especially important, as it sets out the requirements which need to be met before a person can testify as an expert witness. These requirements are:

- The matter in respect of which the witness is called to give evidence should require specialised skill and knowledge;

- the witness must be a person with experience or skill to render him an expert in a particular subject;

- the guidance offered by the expert should be sufficiently relevant to the matter in issue to be determined by the court of law;

- the expertise of any witness should not be elevated to such heights that the court of law's own capabilities and responsibilities are abrogated;

- the opinion offered to the court of law must be proved by admissible evidence, either facts within the personal knowledge of the expert or on the basis of facts proven by others; and

- the opinion of such a witness must not take over the function of the court of law (Kruger, 2008:24-27; Lawrence & Janse van Rensburg, 2006:140).

To conclude, it is evident that social workers must prove their expertise to the court of law, be experts on the matter they are called for, and testify only on matters concerning their specific field of knowledge. The duty of an expert witness is to educate a court of law about a matter, not to take over the court of law's function in any way. In order for social workers to render forensic reports that adhere to the basic legal requirements, they need to be able to write critically and analytically.

CRITICAL-ANALYTICAL SOCIAL WORK FORENSIC REPORT WRITING

The social worker should have the necessary knowledge of critical style elements in order to produce a well-written social work forensic report. Critical style elements include the application of aspects of critical thinking, diagnostic reasoning and the application of these components in the content of the report.

According to Henning, Gravett and Van Rensburg (2005:121), non-personal writing analyses and develops an argument; is subject specific; employs precise and reasoned language; centres on evidence and argument; and acknowledges the ideas of others by citing and referencing them. Critical writing is a form of non-personal writing. According to Paul and Elder (2008), it is the:

"...intellectually disciplined process of actively and skilfully conceptualizing, applying, analysing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness."

Feltham (2010:7) adds that reasons for criticism must be substantiated and that the writer must provide alternative suggestions. Consequently, information that has been gathered by means of a social work forensic assessment must be evaluated by analysing the outcome of the assessment and by reflecting and arguing what the gathered information really means, while providing alternative explanations for the findings. This meaning-giving process is crucial, because it indicates the originality of the written work (Hills, 2011:par.1518). Furthermore, it implies that social workers who write the social work forensic report must argue mentally in an abstract way about their writing as well as during the writing process of the report itself.

There are different types of arguments or modes of reasoning. Delport and De Vos (2011:48-50) mention the deductive reasoning mode, the inductive reasoning mode, and the diagnostic reasoning mode (which is a form of inductive reasoning). In the inductive reasoning mode the premise supports the conclusion (LaBossiere, 2011:par.95). Social workers reason mostly in a diagnostic mode when arguing their findings in their social work forensic reports. The conclusions in a diagnostic mode of reasoning are tentative, but their probability can be strengthened by using literature, for instance, and by excluding certain aspects (Delport & De Vos, 2011:50). The following is an example of the diagnostic reasoning mode:

One of the characteristics of the case:

The child client presents with sexually acting out behaviour.

Tentative generalisation:

According to the literature (specific literature can be quoted), sexually abused children tend to act out sexually.

Diagnostic conclusion:

Therefore, there is a possibility that the child client was sexually abused.

In a social work forensic assessment the psychosocial functioning of a specific client is measured against the existing general theoretical knowledge base. When writing the social work forensic report, the social worker should argue the case according to the principle explained above. It is also vital to argue counter-claims and/or counterarguments in the report (Van den Brink-Budgen, 2010:par.2723). Furthermore, it is of the utmost importance not to cite a single authority as the final authority when measuring a specific client's psychosocial functioning against the existing knowledge base, since it will limit the argument (Feltham, 2010:210). In other words, social workers writing social work forensic reports must be able to formulate their own arguments from different viewpoints, which require thinking and writing on a meta-cognitive level.

In arguing a case, the social worker must adhere to critical writing style elements. The writing of the content of the forensic report should be based on critical style elements within a certain framework. A document that is written critically should have the following basic structure: introduction; discussion; conclusion; evaluation; and recommendations. The writing of the content should be guided by a central thesis, set around identifying a problem and possible solutions (Bowker, 2007:2). The content of the social work forensic report must be written according to certain criteria to make it valid for court purposes. The following eight criteria to write social work forensic reports in a critical and evaluative way are adapted from Paul and Elder (2009:par.243).

1. Purpose: Explain the purpose of the writing. This aspect will be addressed in the introduction of the report.

2. Questions we are trying to answer: The social worker writing the forensic report must set the problem statement in the form of questions such as "Was the child a victim of sexual abuse?" and "Are there alternative explanations?"

3. Information needed to answer the question: The information refers to facts, evidence and/or experience that the writer of the report uses to come to an answer for the above-mentioned questions. Social workers gather information, for instance, by doing social work forensic assessments, and applying different theories, protocols and techniques. This criterion of critical writing can be discussed under the headings "Collateral Information" and/or "Assessment Protocol".

4. Conclusions: After gathering the necessary information and completing the social work forensic assessment, the social worker has to make inferences in order to ascribe value to the obtained information and to make sense of it. This will usually appear in the part of the report headed "Findings".

5. Assumptions: This refers to beliefs we do not question. Therefore, the social worker must question and deconstruct every assumption (Hills, 2011:par.1042). This can be done by applying, for instance, the principle of reductio ad absurdum ("reduction to absurdity") to evaluate the conclusion by assuming the opposite. If the opposite leads to a silly/absurd/practically unacceptable result, then the conclusion can be accepted as valid (Weston, 2009:par.939-953). The following example demonstrates the reductio ad absurdum principle:

To prove: The child presents with age-inappropriate knowledge about sexual activities. Thus, the child was sexually abused by her father.

Assume the opposite: The child was not sexually abused by her father but by somebody else.

To conclude: Assuming the opposite does not lead to absurdity, therefore we cannot prove the argument and we must look for alternative explanations for the finding.

Hence, social workers writing social work forensic reports must critically analyse their reports and base the inferences on theoretically sound, evidence-based information as well as evidence-based forensic assessment protocols.

6. Concepts or key ideas: In order to understand things and to know how to behave in a certain situation, we make use of concepts and ideas. Good critical writers will be aware of the main ideas they utilise during their thinking process (Paul & Elder, 2009:par.294). A forensic report will be based on theoretical concepts and key theoretical ideas. In certain cases the social worker will quote some of the theorists to emphasise a certain issue. According to Bowker (2007:2), if a writer makes a judgment about something, the writer is expected to have consulted a published author's previous work to support her opinion. However, it is desirable that the social worker quote only evidence-based, peer-reviewed theoretical sources.

7. Points of view: Critical writing requires the writer to look deeper than the surface to be able to provide underlying principles, theories and concepts which can, in turn, provide mainstream and alternative explanations for general practices, processes and procedures (Bowker, 2007:3). While writing a forensic report, the social worker, for example, will use Faller's (2007:249) information on alternative explanations for alleged sexual abuse in order to explore and explain the acquired information from the forensic assessment in depth. Providing alternative explanations may demonstrate to the court of law that the assessor has engaged in critical thinking, is objective, and that findings were not taken on face value.

8. Implications and consequences: The last element of critical thinking is to consider the conclusions we have reached based on our thinking and what the possible consequences are (Paul & Elder, 2009:par.313). After assessing a client and interpreting the findings, the social worker will be required to reach certain conclusions and/or make recommendations. Implications and consequences may be addressed in the "Conclusions" and/or "Recommendations" section of the social work forensic report. The social worker now has to provide an answer to the question stated at the beginning of the report. The answer has to be based on the critical thinking process.

Critical writing takes time and requires intensive mental attention. In order to write a social work forensic report of quality, the literature of experts must be drawn upon to strengthen arguments and ground them in a theoretical framework. To make the report authentic, the social worker's own professional voice must be heard in the report and the information should not be a mere repetition of information gathered from the client. In addition, the information must be critically evaluated.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Rubin and Babbie (2011:133) explain that the aim of explorative research is to explore a lesser-known phenomenon, among other things. The lack of literature with regard to the writing of social work forensic reports indicates that this phenomenon is not well known. Hence, the theoretical basis regarding this matter will be broadened with the aim of developing guidelines for the effective and relevant writing of these reports.

A qualitative research paradigm was followed. According to Creswell (2007:39-40), qualitative research is used to explore a phenomenon in great detail, involving the people who experience the phenomenon directly in a specific context. The aim of this study is to provide detailed descriptions of the expectations of court personnel regarding social work forensic reports.

The population of the investigation comprised court personnel (magistrates, prosecutors, private and state lawyers) of the Free State and members of the Child Protection Unit of the South African Police Service (SAPD), Bloemfontein. The number of the different legal professions in the Free State is, according to Moles (2012), as follows: 29 regional magistrates and 60 district magistrates; 42 prosecutors; 40 defence lawyers employed by Legal Aid; and six inspectors of the Child Protection Unit of the SAPD, Bloemfontein.

The sample was obtained by means of non-probability purposive sampling. Krysik and Finn (2010:184) define non-probability sampling as "a procedure in which all the elements in the population have an unknown and usually different probability of being included in the sample". This implies that the sample is not representative of the population and findings cannot be generalised. According to this method of sampling, the researcher decides on the inclusion criteria of the sample (Strydom, 2011:232). In this study court personnel who specialise in criminal law and are currently practising in the courts of the Free State were sampled. The sample consisted of 34 participants practising in the Free State Province, but only a total of 32 members of court personnel took part in the semi-structured interviews. The aim was to conduct interviews with four or five participants per profession. Initially, the participants comprised two judges, three Regional Court magistrates, six District Court magistrates, six prosecutors, six private defence lawyers, seven Legal Aid lawyers and four inspectors from the Child Protection Unit. Twenty-seven participants work with criminal cases, one participant works mostly with civil cases, while the other six participants indicated that they work with both criminal and civil cases.

Different South African races were included in the study, which increases the credibility and relevance of the research. The composition of the participants based on race was as follows: 20 white, nine black, three coloured and two Indian. The ages of the participants ranged from 22 years to 64 years. The majority of participants were in the 35 to 39 and 40 to 44 age categories. This shows that the participants varied in their years of experience, which further contributed to the credibility of the study. The majority of the participants were males.

Data were collected by means of semi-structured interviews. For these interviews the researcher prepared a list of topics, sub-topics or broad questions to serve as a guideline for the interviews. The wording and sequencing of the topics/broad questions were altered during the interviews (Krysik & Finn, 2010:104-105). This type of interview was utilised to obtain opinions regarding the expectations of court personnel in respect of social worker forensic reports.

The raw data were analysed and interpreted according to the generic steps of data analysis as explained by Schurink, Fouché and De Vos (2011:403-404):

- Preparing and organising the data

Planning for recording the data

Data collection and preliminary analyses

Managing the data

Reading and writing memos

- Reducing the data

Generating categories and coding the data

Testing the emergent understanding and searching for alternative explanations

Interpreting and developing typologies

- Visualising, representing and displaying the data

Presenting the data

The data-analysis process is "custombuilt", according to Huberman and Miles (1994, in Creswell, 2007:150), which implies that the steps of data analysis as set out above were not employed in a linear way. Some of these steps were combined and some were carried out simultaneously for practical reasons.

Important ethical matters were addressed. A consent form was given to each participant in which the objectives of the study were explained as well as the fact that participation is voluntarily and that participants could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Confidentiality was also assured. Informed consent was given by all the participants. An interview schedule was used as guideline for the interviews. Consequently, objectivity was increased.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on the analysis of the raw data the following themes were identified and they are discussed below.

Use of social work reports

Participants do make use of social work reports for several different reasons. These reports are used for

(a) adult and youth diversion ("For purposes of diversion as opposed to prosecution of a youth offender");

(b) pre-sentencing purposes ("Reports can play a vital role in the sentencing of convicted accused as they should contain well-researched personal details of the person before the court as well as that of the dependants of the accused"; "To assist me in sentencing criminals especially youthful offenders)";

(c) to determine the impact of an offence on a victim ("Due to the new legislation of the Sexual Offences Act the victim has a mandatory right to a victim's impact report. How it affected their lives, the consequences of the crime and how the victim is coping"); and

(d) to send a person to a rehabilitation centre in accordance with Section 21 of the Rehabilitation Act ("Had one client who was involved with drugs, used the report to suggest rehab instead of a trial of the drug charges against her ").

Although legal professionals do make use of social work research reports, they seldom use such reports during trial and pre-judgment ("Ipersonally have only dealt with such a report once in my seven years so far and that was concerning a five-year-old child and his ability to proceed with testimony after he had testified in chief. He refused to answer questions in cross-examination and a report was then obtained. I believe the same requirements would be applicable to all other reports ").

Poor quality of social work reports

While legal professionals do make use of social work forensic reports, several factors which have a negative impact on the quality of the reports were identified. The participants indicated that they do not receive the reports in good time ("Practical problems, i.e. to get the report in time"); that the reports are of a poor quality ("I would like to but due to the fact that the reports are so poorly drafted, I sometimes feel that it will only be a waste of time and proceed with the matter without the report"); and are usually subjective, with only the accused being interviewed as a resource ("The reports that we receive in court are mostly compiled after a single interview with the accused. None of the information that is received from the accused is confirmed"}.

Improving the quality of social work forensic reports in general

The quality of social work reports could be improved by adhering to the following aspects:

(a) The reports should be provided in good time ("If it is more readily available than at present"); they should be written objectively and well drafted ("Well drafted, researched reports that are objective"');

(b) They should provide more in-depth information ("The more in-depth the contents of the report, the easier it is for the presiding officer to make a fair and informed decision");

(c) They should be balanced - considering, for example, the benefits of the principle of restorative justice, rehabilitation programmes for the accused, and the needs of the accused persons and victims alike ("Expediency and level of depth into the needs of the accused persons and victims alike");

(d) They should be scientific/professional ("Scientifically motivated"; "A report that speaks of professionalism"; "The use of proper language and professional preparation of court reports"; "Reports must be done more professionally and must have knowledge of legislation that they deal with. Not copy and paste").

From the participant statements, it is clear that the social worker must draw upon academic literature in the field of social work to confirm their observations and professional opinion as well as to motivate and strengthen their evaluations and recommendations.

Improving the quality of social work pre-prosecution forensic reports

Pre-prosecution social work forensic reports are mostly used in legal cases pertaining to adult and youth diversion. These types of reports are also required in cases where children have been exposed to any form of abuse. They are then deemed victim impact reports.

Victim impact statements in pre-prosecution social work forensic reports are especially needed if the victim of the crime is a child ("...whether the child will be able to testify and can the child differentiate between lies and telling the truth "; "If child is a victim of sexual offence, report needs to have collateral information - parents, school, etc. Reports can be in English or Afrikaans - according to the child's language").

The participants not only want to know whether a child victim will be able to testify, but also whether secondary trauma can occur during the court procedures ("Is it in the interest of the victim to continue with prosecution. The aim of prosecution is for justice to prevail and for the victim to feel that the offender got his punishment. If the victim will be traumatised further by testifying, the aim of justice is not served and therefore it is better not to continue with the prosecution ").

If the accused is a youth, court personnel expect the social worker to discuss the criminal capacity of that youth, since Section 7 of the Child Justice Act specifies a minimum age for criminal capacity. Section 7(1) of the Act provides that a child under the age of 10 years, who has committed an offence, does not have criminal capacity and cannot be criminally charged. The criminal capacity of youths between the ages of 10 and 14 years has to be proved as specified by Section 7(2) of the Child Justice Act 75 of 2008. Social workers need to possess knowledge regarding legislation and child development, which need to be taken into consideration in the report.

If the report is intended for diversion purposes, court personnel need information about the background of the accused, her psychosocial circumstances and her perception/attitude towards the crime committed ("...highlight the advantages of diversion, alternatively motivating why a youth offender should be put on trial, for example, no positive reaction to previous diversion" ).

From the participants' statements, it appears that pre-prosecution reports focus mainly on the victim (adult or child) and on the child offender.

Improving the quality of social work trial forensic reports

It seems that social worker reports for trial matters are rarely requested and only in extreme cases. The reports must, however, again be detailed ("... giving information on the psychosocial circumstances of the accused, impact of the offence on the victim and the general safety of the community if accused receives alternative sentence") and be prepared in good time ("...would enjoy using them more often if they are on time"; "Timeous availability thereof"). It appears that it is especially during pre-judgment and trial when social workers will be called to testify on their court reports.

Improving the quality of social work pre-sentence forensic reports

Participants indicated that they mostly use the social work forensic report for pre-sentencing purposes ("Reports are mainly required for sentencing purposes. I deal with social reports when assisting with criminal courts for pre-sentence purposes. Reports can play a vital role in the sentencing of convicted accused as they should").

The court personnel expect social workers to obtain background information regarding the accused and to verify this information objectively by gathering collateral information from family members, the employer, school and other relevant people ("I would expect that the social worker interview my client and use the information as background to compile the report. I would further expect that certain information be confirmed independently, especially when children are involved, as this is a very important aspect of sentencing, and also the impact sentencing will have on the family/children of the accused").

Social workers' pre-sentence reports should not only focus on the accused, but also on the family of the accused. Court personnel want detailed reports that illustrate what will happen to the accused person's children and family if that person were to be sentenced to incarceration ("The focus has to be on the children if the female is the primary caregiver - what will happen to the children if their mother is sent to prison? The social worker needs to go into the background of the role the perpetrator plays in the community and family. Best interest of children must be taken into consideration. In cases of children, according to the Child Justice Act, a correctional supervision report is imperative. Need information on the impact of domestic violence on children. Will they be safe if placed with family, will they attend school, will a social worker be monitoring their emotional wellbeing? ").

Participants also indicated that a balanced report is crucial. A magistrate reported in this regard: "... especially when there is a minimum sentence for a sexual offence, then a victim impact report is also needed" .

Three aspects must be addressed in a pre-sentence social work forensic report. Firstly, the social worker must address the psychosocial circumstances of the accused, as the report will play a vital role in determining the type of punishment the convicted will receive ("...the social background and current living conditions"; "the employment record and income "; ''the financial position and ability to pay a fine or compensate the complainant for losses incurred as a result of the crime and the willingness of the accused to do so" ). Secondly, the social worker needs to focus on the motive for committing the crime and the attitude towards the crime ("... the attitude of the accused towards the crime convicted of and the reasons provided for the commission of the crime"; "I would like to know firstly why my client did what he did"; ". remorse shown and the reasons." ). Thirdly, the social worker needs to evaluate the offender's rehabilitation potential and recommend proper mandatory therapeutical programmes (" . the willingness of the accused to participate in treatment programmes - if specific problems might be present - and recommendations of specific available programmes in the area where the accused resides ").

In order to write a balanced, objective pre-sentence report social workers need to take into account the impact of the offence on the victim ("... the emotional impact on the victim "; "its impact on the victim and whether alternative dispute resolution should be followed or normal prosecution be implemented"; "give sufficient background information on the victim and the impact of the offence on the victim" ).

Personal contact with the social worker

Court personnel also expressed the need to know the social workers working in their court jurisdictions and to develop a professional relationship with them ("More cooperation between social workers and magistrates. Social workers must ask magistrates why they want a report/what the focus of the report must be if it is unclear" ). If court personnel were to know the social worker from whom they request a court report, the researchers are of the opinion that they will be more motivated to request reports.

A need for more social workers

It became evident that more social workers are needed. Participants would even like to have social workers based at the court to be available at all times to assist them ("More social workers need to be available at the courts to assess victims and offenders alike"; "Their availability to assess and assist needs attention"). However, there is a serious shortage of social workers. There are, for instance, not enough registered social workers "to provide the social welfare needs of children in terms of the Children's Act of 2005" (SAIRR, 2012). Thus, this need expressed by the participants will most probably not be fulfilled in the near future.

CONCLUSION

The research has indicated that social work services are needed in courts. Social workers can assist the court in two ways, namely by providing social work forensic court reports, and by testifying as expert witnesses in a court of law. To assist the court, social workers should comply with the aspects indicated below.

Social workers must have in-depth knowledge regarding the legal discourse in social work. Knowledge of aggravating and mitigating factors as well as the principles of sentencing and the types of sentences is of the utmost importance to assist the court in making effective decisions. In-depth knowledge of the legal discourse in social work is not sufficient to deliver quality social work services. The social worker must also be adequately trained to do social work forensic assessments, because no report can "rectify" a flawed assessment.

A social work forensic report can be requested at any time during the court trial procedures, which can vary from a preliminary inquiry report to a pre-sentence report. The purpose of each forensic social work report must be borne in mind, as this will determine the factors that the social worker will have to consider during the assessment.

The social worker must also be aware not only of the relevant psychosocial factors, but also of the legislation involved from a legal perspective.

Four main aspects must be addressed when writing a social work forensic report: the accused, the victim, the community, and the children involved (either as the direct or secondary victims, or accused). Social workers should elaborate on these aspects so that a just verdict and/or sentence can be returned that will be in the best interest of all parties involved. Critical-analytical thinking and writing principles must be followed to produce a high-quality social work forensic report. Critical-analytical thinking and writing principles entail, among others, interpretation, evaluation and the theoretical explanation of information obtained from the client system. The social worker therefore uses existing theory and methodology to explain certain aspects of a client's behaviour. Diagnostic reasoning is the method by which the above processes occur, when the social worker reasons from the general theory to the specific about the client's behaviour and reaches certain conclusions and makes certain inferences. Also, due attention must be paid to the referencing of authors whose work is utilised in the report. References not only give authors the necessary acknowledgement, but also indicate that the social worker has researched the aspects addressed in the report.

Social workers can be called as expert witnesses in order to prove to the court that their evidence will promote the fairness of the case and the human rights of the client. This implies that the social worker must be well qualified regarding the psychosocial functioning of the accused and/or victim (for example, the trauma image of the child or the dynamics regarding incest) to form an opinion about the case. Social workers should furthermore refer to aggravating and mitigating factors when testifying in court as an expert witness.

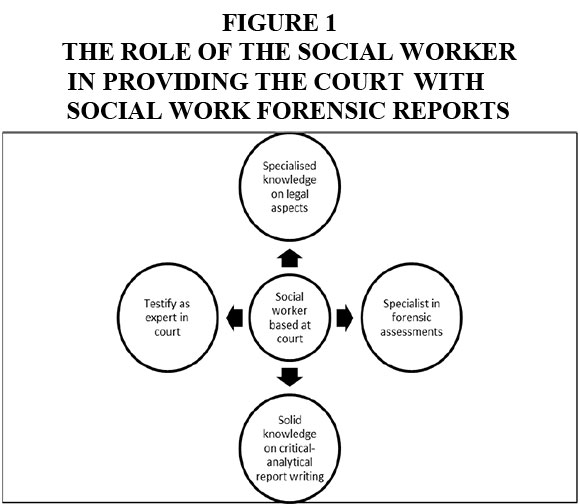

The concluding remarks are summarised in Figure 1, which serves as a model for further investigation and training, as discussed below under "Recommendations". Figure 1 shows that the social worker must preferably be based at the court, specialise in legal aspects, be a specialist on the theory and practice of social work forensic assessments, and be able to write social work forensic reports based on critical-analytical thinking and sound writing principles. Finally, based on the above-mentioned aspects, the social worker must be able to testify in court as an expert witness.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The guidelines for writing social work forensic reports are outlined below as recommendations for evidence-based practice. This should not be seen as a pro forma format for social work forensic reports, but as broad guidelines instead, as the court expects and requires written social work forensic reports that uniquely address the specific case.

The following information should be included and critically discussed and evaluated in the pre-prosecution report: Indicate whether the victim will be emotionally ready to testify in a court of law and the possible impact of delivering the testimony, taking the psychosocial impact of cross-examination and secondary abuse into consideration. For children, either as victims or offenders, the following must be addressed:

- collateral information from parents, family, school, etc.;

- whether the child will be able to testify;

- whether the child can differentiate between lies and telling the truth;

- the criminal capacity of a child between 10 and 14 years; and

- the same detailed information and evaluation thereof as mentioned under the pre-sentence report.

For the pre-sentence report the following aspects must be critically discussed and evaluated.

- The accused: social background and current living conditions; level of education; employment record and income; financial position and ability to pay a fine or compensate the complainant for losses incurred as a result of the crime, and the willingness of the accused to do so; the attitude of the accused towards the crime of which they are convicted and the reasons provided for the commission of the crime; remorse shown (the feelings of the accused towards the victim) and the reasons for this; health record and current health status with special reference to drug or alcohol problems and whether these played a role in the commission of the crime; consequences for the dependants of the accused, should the accused be sentenced to direct imprisonment; willingness of the accused to participate in treatment programmes (if specific problems are present) and recommendations of specific available programmes in the area where the accused resides; consequences of the crime for the accused and his family; possibility of rehabilitation; the possible impact of the sentence; and what a just proper sentence would be.

- The trauma impact of the crime on the psychosocial functioning of the victim. Also important is an exposition of the victim's psychosocial functioning before the exposure to the crime.

- The interest of the broader society and the specific community should be taken into consideration, critically discussed and evaluated.

To write the forensic reports mentioned above, social workers can rely on a combination of clinical and ecometrical assessments, in which they need to be well trained. They also need to be experts on the psychodynamics of offenders and victims alike as well as in the legal discourse of social work. Training in critical thinking and writing, and sound report-writing skills are also highly recommended.

The employment of social workers based at courts of law can be investigated on a practice-policy level. If such a need is established, negotiations with the applicable governmental bodies can be initiated.

On an academic/theoretical level, social workers can initiate a multi-professional training unit at tertiary institutions where the legal discourse should be the central driving force to achieve the above-mentioned aims. Social work, forensic nursing, psychology and drama skills (for instance, teaching expert witnesses how to project their voices when they testify) could be part of such a multi-professional training and research unit. This can be executed on different educational levels, depending on the capacity of the relevant tertiary institution, namely certificate, postgraduate diploma and a structured master's degree.

The written forensic reports of social workers can be researched by means of qualitative content analysis to identify common errors regarding critical-analytical writing, the application of academic writing skills as well as technical errors. The information can be utilised to develop and/or adapt training of the social worker who is doing forensic work.

REFERENCES

BOWKER, N. (ed). 2007. Academic writing: a guide to tertiary level writing. Auckland: Massey University. [ Links ]

CHILD JUSTICE ACT NO. 75 of 2008. See Department of Justice, South Africa. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed). London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DELPORT, C.S.L. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Professional research and professional practice. In: De VOS, A., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, SOUTH AFRICA. 1988. Law of Evidence Amendment Act No. 45 of 1988. Government Gazette, Vol. 274, No. 11274 (22 April). Pretoria: State Printers. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, SOUTH AFRICA. 2008. Child Justice Act No. 75 of 2008. Government Gazette, Vol. 527, No. 32225 (11 May). Pretoria: State Printers. [ Links ]

FALLER, K.C. 2007. Interviewing children about sexual abuse: controversies and best practice. New York, NY: Oxford Press. [ Links ]

FELTHAM, C. 2010. Critical thinking in counselling and psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, E. 2010. Expectations of social work forensic reports [personal interview by Joubert, M.]. 6 August, Welkom. [ Links ]

HEALY, K. 2005. Social work theories in context. Creating frameworks for practice. New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

HENNING, E., GRAVETT, S. & VAN RENSBURG, W. 2005. Finding your way in academic writing (2nd ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

HILLS, D. 2011. Student essentials: critical thinking. Richmond: Trotmin. [Kindle ed. Online Available: http://www.amazon.com]. [ Links ]

JOUBERT, C. 2010. Applied law for police officials (3rd ed). Cape Town: Juta Law. [ Links ]

KLEYN, D. & VILJOEN, F. 2002. Beginnersgids vir regstudente (3rd ed). Cape Town: Juta Law. [ Links ]

KRAFTT, E. 2011. The use of social work reports as evidence in courts [personal interview by Joubert, M.]. 19 January, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

KRUGER, A. 2008. Hiemstra's criminal procedure. Durban: LexisNexis. [ Links ]

KRYSIK, J.L. & FINN, J. 2010. Research for effective social work practice (2nd ed). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

LABOSSIERE, M.C. 2011. 30 More fallacies. (version 1.1). [Kindle ed. Online Available: http://www.amazon.com]. [ Links ]

LABUSCHAGNE, C. 2010. Expectations of social work forensic reports [personal interview by Joubert, M.]. 12 April, Welkom. [ Links ]

LAW OF EVIDENCE AMENDMENT ACT NO. 45 of 1988. See Department of Justice, South Africa. [ Links ]

LAWRENCE, B. & JANSE VAN RENSBURG, K. 2006. Forms of sexual abuse and the practical implications of applying South African law to sexual offences cases. In: SPIES, G.M. (ed), Sexual abuse: dynamics, assessment and healing. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

MOLES, J. 2012. Information on the number of the different legal professions in the Free State [personal interview by Joubert, M.]. 26 June, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

MUJUZI, J.D. 2013. Hearsay evidence in South Africa: should courts add the 'sole and decisive rule' to their arsenal? The International Journal of Evidence & Proof, 347366. [ Links ]

NAUDÉ, H., DU PREEZ, C.S. & ZWIEGERS, T. 2005. Forensiese sielkundige verslagskrywing in sake van betwiste toesig en beheer oor minderjarige kinders. Child Abuse Research in South Africa, 62:56-72. [ Links ]

NWU (North-West University). 2012. Yeasrbook: Calender 2012. Faculty of Health Sciences. Post graduate. Potchefstroom Campus. [Online] Available: http://www.nwu.ac.za/sites/www.nwu.ac.za/flles/images/yearbook_postgraduate_e.pdf [Accessed: 03/06/2014]. [ Links ]

OPPERMAN, L. 2012. Hearsay evidence in courts [personal interview by Joubert, M.]. 21 March, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

PAUL, R. & ELDER, L. 2008. Defining critical thinking. Foundation for Critical Thinking Press. [Online] Available: http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/410 [Accessed: 09/06/2012]. [ Links ]

PAUL, R. & ELDER, L. 2009. The aspiring thinker's guide to critical thinking. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. [Kindle ed. Online Available: http://www.amazon.com]. [ Links ]

PILLAY V THE STATE (739/10) [2011] ZASCA 111. The Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa judgement. [Online] Available: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZASCA/2011/111.pdf. [Accessed: 14/05/2013]. [ Links ]

RUBIN, A. & BABBIE, E. 2011. Research methods for social work (7th ed). International ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

SACSSP (South African Council for Social Service Professions). 2010. Professional conduct: frequently-asked questions. [Online] Available: http://www.sacssp.co.za/website/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/SACSSP-Pamphlet-FAQ1.pdf Vol. 1 November 2010. [Accessed: 02/06/2014]. [ Links ]

SAIRR (SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS). 2012. Social worker shortage undermines effectiveness of social welfare legislation. [Online] Available: http://www.sairr.org.za/media/media-releases/Social_worker_shortage.pdf/view?searchterm=social%20workers. [Accessed: 02/06/2014]. [ Links ]

SCHURINK, W., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Qualitative data-analysis and interpretation. In: De VOS, A., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

SCHWIKKARD, P.J. & VAN DER MERWE, S.E. 2002. Principles of evidence (2nd ed). Cape Town: Juta Law. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. 2011. Sampling and sampling methods. In: De VOS, A., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds), Research at grass roots: for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

VAN DEN BRINK-BUDGEN, R. 2010. Advanced critical thinking skills. Begbroke: How To Books. [Kindle ed. Online Available: http://www.amazon.com]. [ Links ]

WESTON, A. 2009. A rulebook for arguments (4th ed). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing. [Kindle ed. Online Available: http: //www.amazon.com]. [ Links ]