Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.2 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-2-395

ARTICLES

The evaluation of a training programme based on paulo freire's views on community practice: A south african example

Hanna Nel

Department of Social Work, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A training programme in personal leadership, directed at facilitators of community practice, based on the principles and methods of Paulo Freire's approach, was applied and evaluated in an African context. The nature of the training programme was student centred, and implemented in a participatory consciousness-raising and experiential way. The purpose of this article is to report on the evaluation of the programme, which was conducted by means of an exploratory, descriptive and contextual strategy of inquiry pursued within a qualitative paradigm. Practice guidelines derived from the findings indicated the importance of facilitation methods that raise consciousness in the process of transformation.

INTRODUCTION

Although Paulo Freire was a pedagogue, his approach has contributed to community education and practice worldwide (Foote, 2010; Krajewski, Lockwood, Krajewski-Jaime & Wiencek, 2011; Rafi, 2003a). For students to understand and be able to apply participatory people-centred approaches in community practice, it is evident that teaching methodology should be student centred, experiential and participatory in nature (Burkey, 1993; Johnson & Johnson, 1994; Rafi, 2003b; Swanepoel & De Beer, 2006). It is also evident in this study that the teaching methodology has to focus first on the personal leadership development of students before they can be successful as community practitioners (Brueggemann, 2006; Green, 2008; Homan, 2004; Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). Critical consciousness raising and reflection has to be integrated throughout teaching and learning to enable students to change. Educators often find it challenging to teach people-centred participatory community development approaches in this way (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire 2008; Krajewski et al., 2011).

Paulo Freire is one of the contributors to the understanding of people-centred community practice (of which others are Robert Chambers, 1983; David Korten, 1990; Max-Neef, 1991). Freire's approach is both an approach for people-centred community practice as well as a methodology for teaching and learning. His approach is based on the beliefs that "people are able to think critically about their situation, can be trusted to take control of their lives, and collectively transform their views of the world and how they relate to it" (Schenck, Nel & Louw, 2010:86). In the teaching of students to integrate and apply these beliefs to the communities they are facilitating, students have to be able to first experience and apply these beliefs to their own lives. For students to experience these beliefs on a personal basis, participatory, people-centred, experiential teaching methods and principles have to be applied in a skilful way by facilitators. Freire's approach has been applied in many countries of the world, especially Latin America, and various disciplines such as anthropology, education, social work, nursing, medical science, development studies and psychology (Adair, 2008; Blackburn, 2000; Burstow, 1991; Finlay & Faith, 1980; Freedman, 2007). Freire's approach has also been applied in South Africa, but to a lesser extent and primarily in education, business studies, theology and social work (Dreyer, 2000; Nhlanhla, 2010; Ntakirutimana, 2010; Nyeberah, 2010; Theron, 1993). The main conclusion that many of these studies arrived at was that a critical consciousness of their everyday experiences should be created before real transformation could take place.

This article will first discuss a conceptual framework of Paulo Freire's approach. Secondly, the training programme offered to students will be attended to. Thirdly, the research methodology applied in the study will be addressed, followed by the findings and conclusions.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF PAULO FREIRE'S APPROACH

Paulo Freire (1921-1997) was a Brazilian pedagogue who revolutionised ideas on poor and oppressed people, with the primary aim of addressing oppression through an approach that develops critical consciousness and promotes liberation (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Schenk et al., 2010). This section provides a conceptual framework by firstly emphasising the "culture of silence" and the "banking" concept of education. Secondly, the principles underlying his approach will be explored. Thirdly, attention will be given to the methodological process, and lastly, three leadership styles, with specific reference to the democratic, passive and autocratic leadership styles, will be analysed and linked to Freire's approach.

Culture of silence

One of the main themes explored in many research studies, namely a "culture of silence", was highlighted by Freire (Barnes & Fairbanks, 1997; Brigham, 1977; Ntakirutimana, 2010). When people are deprived or oppressed, a "culture of silence" about their condition develops (Freire, 1994). The culture of silence exists in relation to the dominant culture of the oppressor or invader, and it is part of a larger social complex and not an isolated independent phenomenon (Kidd & Kumar, 1981). Any culture is established over a long time through generations, which is the "way people structure their experience conceptually, so that it may be transmitted as knowledge from person to person and from one generation to the next" (Schenk et al., 2010:79). A "culture of silence" develops in the same way.

The oppressors or invaders and the oppressed or invaded are two primary groups of people in any society. Oppression gradually takes place explicitly and implicitly, and the oppressed people often become "voiceless and without choices" (Chambers, 1983:66), apathetic and subtly submerged into the culture of the oppressors. They become dependent on the oppressors, and feel inferior as well as alienated from their own culture. Those invaded start thinking of themselves as unworthy, without an opinion or voice. This dependence often leads to exploitation and the invaded are seen as backward by the invaders.

The oppressors or invaders often prevent those invaded from sharing in the wealth and resources available to the invaders. The invaded become dependent on the invaders, whom they try to maintain, and the invaded usually look for guidance from the oppressors because they do not know how to live in the new way. The invaded become followers of the invaders and often cannot participate as equals. The invaders exploit the dependence of the invaded and if the exploitation is carried too far it can often lead to resistance, violence and revolt, which have no advantages for the oppressors (Freire, 1994; Schenck et al., 2010).

This concept of a "culture of silence" is relevant within the context of South Africa for many reasons. One is that black people were oppressed during the apartheids years, became alienated from their own culture and way of living, and became dependent on more influential people for survival. In the process they lost their voices and became powerless, with no choices. Another reason why this concept is relevant in South Africa is the many forms of oppression that exist such as gender oppression (usually men oppressing women), bosses' oppression of employees, teachers' oppression of learners, parents' oppression of children, etc. (Mosoetsa, 2011; Singer & Shope, 2000).

The "banking concept of education" versus facilitation of the problem-posing method

Freire notes that the "banking concept of education" entails the educators "depositing" information into their students. "Depositing" information "hinders the intellectual growth of students by turning them into receptors and collectors of information that have no real connection to their lives" (Micheletti, 2010:2). Because people are receptors and collectors, they are regarded as objects with empty minds passively receiving deposits of (supposed) reality from people outside. They have no independence and therefore no ability to rationalise and conceptualise knowledge at a personal level (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008). This "banking concept of education" is premised on the belief that knowledge is perceived as "a 'gift' to be bestowed by teachers upon voiceless, patient, ignorant students" (Roberts, 1996:296). This in turn, according to Micheletti (2010:2), results in a state of affairs where "a person is merely in the world, not with the world or with others; the individual is a spectator, not re-creator". The banking method represents a structure of oppression and control.

Freire postulates that true education is a liberating and active educational process, which allows people to become intellectually and genuinely engaged with the learning material and responsible for understanding the material (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Krajewski et al., 2011). Both students and teachers are engaged in dialogue to acquire knowledge and experience from each other (Micheletti, 2010). This dialogical process should be authentic and creative, and has to take place with sympathy and love (Blackburn, 2000). The facilitator assists students to draw from each other's life experiences and use the resources of knowledge, feelings and experiences of each student. Through effective facilitation students become engaged in processes of active experimentation with concepts and ideas that may prove useful and meaningful for the accomplishment of students' objectives and development aspirations (Affolter, Richter, Afaq, Daudzai, Massood, Rahimi & Sahebian, 2009). Both facilitator and students are collaboratively concerned with the functioning of the community or society, and by experiencing discomfort the students will most probably develop direction for their own lives. Facilitating in this way makes it more likely that, when students work with community members, they will relate to community members in the same way (Brigham, 1977).

Reflecting on the approach of Freire, the training programme in this study emphasises an experiential, authentic, relational, interactive team approach between the facilitator and participants, where everybody contributed to the conscientisation process and the transformation of all involved. In the facilitation process the relationship between the facilitator and the participant/learner was seen as the primary ingredient (Johnson & Johnson, 1994; Laird, 1985; Nelson-Jones, 1991).

Principles of training

Derived from research studies (referred to in the discussion below) and Freire's pedagogy, the principles outlined below are relevant for training programmes in general and this training programme on community development specifically.

- People are knowledgeable and not empty vessels into which knowledge and information can be deposited. People can be trusted with information and be reliable, and they will change society into a more just society (Krajewski et al., 2011). The belief that participants have the ability to think abstractly and critically, and be able to learn through self-reflected learning, should form part of all training sessions (Schenck et al., 2010).

- Training should be based on the power of collective action, where participants dialogue with each other in a respectful and collaborative way. Learning is therefore relational and knowledge is produced through interaction with each other and with the world (Bartlett, 2005). People "learn, remember and apply more aspects they discover in dialogue than aspects they are told by experts" (Schenck et al., 2010:76). To be successful in dialogue and collaborative activities, it is important that the facilitator and students trust and accept each other, and provide a sense of safety and empower each other.

- The training programme should be structured in such a way that participants educate each other within their frame of reference, experiences, realities, values and culture. The training programme should also be based on issues that are relevant and important to them and the community. Addressing relevant and important issues will encourage them to express their views and inspire them so that their self-driven collective actions change their reality (Freire, 2008).

- By engaging in a collective process of conscientisation within their situation, using problem-posing methods instead of the banking method of depositing information, participants will take control of their lives. Conscientisation is a process for raising the self-reflexive awareness of people rather than passively educating and instructing them. The development of a critical consciousness will enable participants to break out of the "culture of silence" and encourage them to speak and take control of their lives (Schenck, 2002; Schenck et al., 2010).

- The relationship between the educator/facilitator/trainer and the trainees/participants has to be equal, where the roles of participants and facilitator become less structured (Freire, 2004). Roberts (1996:303) is of the opinion that liberatory education is an individual and collective activity of teachers and students "investigating the object of study through purposeful, directive, structured, critical dialogue".

- Change is perceived as radical transformation on many levels, namely in individuals' lives, the community, the environment and the entire society over time (Roberts, 1996). In this training programme change was primarily envisaged as taking place in the individuals' lives and only to a certain extent within the community. Transformation is based on the vision of a more just society, with values of cooperation, justice and concern for the common good (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Schenck et al., 2010).

Process of transformation

The methodology of Freire's pedagogy is a critical reflective process in which people explore and understand their world and find their own solutions, and in the process address their own feelings of resignation towards their poverty; it is geared towards the liberation of the poor from economic, social and political oppression (Rafi, 2003b; Schenk et al., 2010). The process requires the active engagement of participants, breaking through apathy and developing critical awareness of the causes of problems (Foote, 2010; Henderson & Thomas, 2002; Hope & Timmel, 1995; Rafi, 2003a).

There are two distinct and sequential steps in the transformation process: firstly, people become conscious of their reality of oppression, and secondly, the oppressed have to emancipate or liberate themselves from their oppressors and situations of oppression (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008).

For the duration of the first step of the conscientisation process participants become aware of, and start to understand through self-enquiry and analysis, the factors blameable for their condition (Matheson & Matheson, 2008; Rafi, 2003b). It is a dialogical collective-oriented critical awareness process in identifying issues of oppression (Burstow, 1991; Rafi, 2003a). It is an on-going co-learning process through which new forms of "knowledge, reality and power relationships can develop to challenge oppressive conditions and power structures" (Schenck et al., 2010:77). The next step in the conscientisation process is to challenge the social and political structures that oppress them. The facilitator assists participants to identify assets and strengths in their historical tradition and culture which enhance their dignity and power, and then to apply relevant new knowledge to them. The conscientisation and change processes are facilitated through a continuous process of action-reflection-action. During this process of action-reflection-action, participants explore aspects and causes of oppression, followed by taking action. After that they reflect critically on what has happened in the action, followed by change, which consequently paves the way for further action (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Rafi, 2003b). Rafi (2003a) is of the opinion that participants should be capacitated to bring about sustainable change. These activities of participants have to be rooted in the awareness and consciousness of the participants.

Leadership styles

In addition and complementary to Freire's approach, the trainer included the three leadership styles, namely autocratic, democratic and passive, in the training programme. An autocratic leader could be described as somebody who has absolute power, sets goals and policies, dictates the activities of the members, develops major plans, presents the decisions to followers, and allows no questions or opposing points of view. This leadership style complements the characteristics of the oppressor or invader. This conventional style of teaching, which prevails in most schools and universities, embodies a pattern of dominating "relationships between those who teach and those who learn". A power structure is involved which "allows the educator to control what the student should know" (Quinn, 1982:53). In contrast, the democratic leader seeks maximum involvement and participation of every member in all decisions affecting the group and attempts to spread responsibility rather than concentrate it. The democratic leadership style complements Freire's pedagogy in the sense that human beings are concerned with making the world a more human and liberating place for all. They do not need to be the oppressed and invaded (autocratic style), but could with others become co-creators of their lives. A passive leader participates very little and group members are generally left to function with little input. Group members in community groups seldom function well under a passive leadership style, which may be effective only when the members are committed (Daft & Marcic, 2004; Zastrow, 2009). In South Africa it seems that autocratic and passive leadership styles are the common trend and this should be addressed (Singer & Shope, 2000; Williams, 2004).

TRAINING PROGRAMME ON PERSONAL LEADERSHIP

The two-day training module with a focus on personal leadership was offered to 22 students enrolled for a certificate programme in Community Development at the Department of Social Work at the University of Johannesburg. The entire certificate programme was implemented over a period of nine months. The two-day training module was based on Freire's approach with the aim of addressing oppression and free participants from maintaining a "culture of silence" on primarily a personal basis. The programme was mainly focused on the creation of a process of critical consciousness in relation to different types of oppression, discrimination, segregation and rejection. The focus was to facilitate students to become aware of the different types of oppression they experienced. The training programme also focused on the establishment of strategies on how to deal with these feelings and memories of past experiences on a personal and community basis. Different participatory exercises were facilitated on an individual basis, in small groups and within the entire group of 22. The exercises were creative, culturally sensitive and participative in nature. Although a manual was handed out to the participants, the programme was adjusted according to the needs of the participants. Role plays and simulation games were also applied in the workshop. Different tools and aids were employed, such as balls and cards for card games, made by the facilitator. The facilitator basically followed Freire's pedagogical methodology of awareness raising described in the section above. The theory utilised in the training programme was based on the approach of Paulo Freire and the three leadership styles, namely democratic, autocratic and passive styles. The theoretical components of each leadership style were explored, followed by an exercise in which each student had to decide what kind of leader he/she is, identification of strengths and weaknesses as a leader, and ways to change or improve as a leader. After that students discussed in small groups which leadership styles prevails in the group and what needed change or improvement. The three leadership styles were integrated into the training programme because of their relevance to the situation in South Africa. Although South Africa has promoted a democratic society for nearly 20 years, there is still oppression on different levels, namely at home, at work and in society at large.

The facilitator of the workshop, who lives in Canada, is a qualified social worker with a master's degree in Clinical Practice in Social Work, and underwent a six-month training workshop with Paulo Freire in Brasilia. She has had extensive experience in the application of Freire's methodology over the last six years.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In order to explore and describe the effect of the workshop based on Paulo Freire's views, a qualitative research approach was adopted, since this approach explores, describes and explains people's experiences, behaviours, interactions and social contexts (Delport, Fouché & Schurink, 2011). An exploratory, descriptive and contextual strategy of inquiry was pursued within a qualitative paradigm. A non-probability sampling technique, namely convenience sampling, was used, based on the availability of the students (Strydom & Delport, 2011). Twenty-two students participated in the training programme, seven of whom were available for the interviews. The author/researcher was an observer for the duration of the implementation of the two-day workshop, and made observational notes on the methods, processes and facilitation. These notes were included in the analysis and interpretation of findings. Individual interviews were conducted with the seven participants fourteen months after the workshop and five months after the completion of the entire certificate programme. The duration of an interview was between 60 and 90 minutes. Issues of confidentiality and anonymity were clarified with the students and permission was received from participants to use an audio recorder during the interviews. The main question asked was "What was the effect of the workshop of Paulo Freire's methodology on your personal life and work in the community?" Probing questions were asked followed the main question in reaching the goals of the research. The researcher's aim was to explore the effect of the two-day workshop based on Freire's approach and not the entire nine months' certificate programme on community development.

A bottom-up inductive approach was primarily utilised, moving from the specific to the general, using an informal logic, open-ended, exploratory approach (Delport & De Vos, 2011). Content analysis was done by applying the following steps:

- Read through the data twice to obtain a general sense of what they cover and make some general notes;

- Read through the data a third time to look for answers to the research question and start identifying units of meaning and assigning codes to these units;

- Develop categories by organising codes into categories, moving from units of meaning to coding and then to categories by constantly comparing the data units (constant comparison method);

- Organise codes and categories according to themes from the data and from the theory;

- Take each theme and select quotes (in vivo codes) that represent units of meaning;

- Analyse the themes and link to literature (Grbich, 2007; Henning, 2004).

Freire's approach primarily guided the researcher in the analysis of the data.

For the purpose of data verification, the researcher employed Guba's model of trustworthiness (Creswell, 1998; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Primarily, two procedures were used to enhance the credibility of the data, namely prolonged engagement and member checking. The researcher was an observer in the workshop, which enabled her to familiarise herself with the participants and Freire's approach. Trust was built with the participants during this period. Member checking for the confirmation of findings was also applied in the project through the discussion of findings with the participants in a group.

FINDINGS

The findings are presented on two levels, namely the profile of participants, and the themes which emerged from the interviews.

Profile of participants

The seven participants interviewed were black, which was representative of the class of 21 black Africans and one white woman. Three participants were women and four were men; their ages ranged from 20 to 35. Two women were married with two children each, while the others were unmarried and had no children. All the participants worked for non-governmental organisations (NGOs). All the participants were in possession of a final school year (matric) certificate.

Themes which emerged

Three main themes emerged through the analysis of the data: characteristics of a competent facilitator, transformation on a personal level, and transformation on a community level.

Theme one: Competence and characteristics of a facilitator

It was evident that the facilitator was competent in applying Paulo Freire's methodology and approach in the workshop. The participants found the way that the facilitator planned and facilitated the workshop quite profound and inspiring. The content of Paulo Freire's theory was not explicitly discussed, but because of effective facilitation, the participatory experiential methods and techniques adopted, and on the basis of their living experience, participants became aware of their own situations and discovered the strengths to change them. The facilitator perceived all the participants as conscious beings, who through the relationships and connections in class, drew from the learning material and facilitation and applied what they had learned to their lives. True comprehension took place through deep dialogue, questioning, sharing of each other's opinions and solving problems together. In this problem-posing method of education both the facilitator and participants became "subjects of the educational process by overcoming authoritarianism and an alienating intellectualism" (Micheletti, 2010:2).

The facilitator was not only excellent in her facilitation skills, but her entire approach as a human being made an impression on the participants. The facilitator touched both their hearts and minds, and participants said it was a "mind-training" and "mind-changing" programme, and "six months after the workshop we feel that her spirit is still with us". This finding confirms that effective facilitation occurs when facilitators establish an egalitarian teacher-student relationship by implement a dialogical, problem-posing process, pay attention to their relationship with participants, and listen especially to the feelings of participants (Burkey, 1993; Finlay & Faith, 1980; Laird, 1985; Mocombe, 2005; Nelson-Jones, 1991; Swanepoel & De Beer, 2006).

It appeared that the following areas of competencies and characteristics of facilitation were highlighted by participants.

- The facilitator was a role model for participants - they identified strongly with her. She not only motivated them to become responsible and accountable people on a personal basis, but also enabled them to guide people in their communities to take ownership of their own lives. She was honest about her background of oppression and able to share it with the group. They noticed that the facilitator was "healed" on a personal level, which seemed an important dimension of successful facilitation. A response in this regard was, "She mentioned a lot of where she comes from and the poverty she went through and this left us with hope", and "she has lived it, she has seen it, she has experienced it".

- It appeared that the workshop was facilitated in an effective way. Participants mentioned the creative, experiential, playful way in which the workshop was facilitated, using various games and activities such as ice-breakers, plays, games (such as self-made board games by the facilitator), meditation and dancing. "Those exercises, the games that she gave us, they were so fantastic, the meditation was wonderful"; "it was done in a playful way". Some of the participants mentioned that they have applied the games and activities in their work as community facilitators.

- A safe atmosphere was created to allow participants to share confidential issues in the workshop. A response in this regard was "She teaches us to trust each other"; "...especially of making you feel at home"; "You know that you must participate"; and "They [participants] become open".

- The facilitator was also able to initiate deep dialogue in class in both the entire group and in the small discussion groups. She was able to encourage the participation of all participants and created team work.

- Participants were impressed with the facilitator's democratic leadership style and were convinced that this is the only style to be applied within the context of community development. The autocratic leadership style was associated with oppression and abuse. Her approach prompted the following response from a participant: "She said she came from an oppressive situation and therefore hates authoritarian leadership".

The above characteristics of a competent Freirian facilitator correspond with the findings in the literature on facilitation (Blackburn, 2000; Burkey, 1993; Mocombe, 2005; Toseland & Rivas, 2005; Zastrow, 2009).

Theme two: Transformation on a personal level

It appeared that the participants went through a four-stage transformation or healing process on a personal level. Firstly, participants became aware of oppressive experiences and their effects on their lives. Secondly, by sharing these experiences with other participants, healing started to take place. Thirdly, they became aware of the power and strengths within themselves, and finally, they reached a stage where they started taking charge of their lives.

During the first stage of the transformation process, participants became aware of situations of oppression. Participants became conscious of experiences of rejection, abuse and exploitation, and revealed these experiences as well as various situations of oppression, e.g. when they were abused as children by parents and family members, the abuse of their mothers by their fathers, as well as abusive and oppressive situations at school and work. In this regard, one participant mentioned, "my mother, she told me [that she] was abused when she was pregnant with me, later I was abused by an uncle". Another participant said, "The Mathematics teacher said I will be this vulgar person who robs other people". A third person said, "I never felt that I could make a contribution in a meeting at work".

Participants mentioned the value of sharing these oppressive situations with each other (second stage). Responses of participants included: "...as part of the healing process you must open up on the bad things that happened in our lives"; "...you need to cry, let it go, let it go; then you feel free"; and "... focus on the areas that were un-dealt with; you deal with them, because sometimes we cannot do well because we have grudges with all the hurts that are always clinging in our lives". Another participant said "First find out who you are and where your weaknesses are so that you can relate to people who are maybe weak on certain issues and try to put yourself in their shoes and see how to move with them". Participants felt that being open and honest about their own weaknesses and experiences of oppression created a situation where others also become open about their past experiences.

Through the discovery of situations of oppression, they became aware of the effect of oppression on their lives, like losing their own values, identity and self-esteem, becoming dependent on others, and not knowing who they really are. A response in this regard is: "Don't lose our values, but speak up". These findings correspond with studies done on Freire's approach (Blackburn, 2000; Burstow, 1991; Mocombe, 2005).

During the third stage of the transformation process, participants discovered their own strengths, views, values and feelings. They realised each participant's uniqueness and became aware of the fact that they should stand up for who they are. They also distinguished between the values and beliefs of oppressors, engraved in them over many years versus developing their own values and beliefs. They experienced this as a turning point, shifting from power that resided outside of themselves to generating power within themselves. Participants emphasised it as being a "mind-changing" and "healing" process. Responses of participants were: "People have power inside themselves but they don't know it", from a stage of "I cannot do it to I can do it", from a stage of "I have not to I have". Another comment was, "It was a turning point, a very big impact on my life".

They realised that despite oppressive situations in their lives, they all have strengths and assets. They mentioned that they changed their paradigms from what they do not have and their weaknesses to an appreciation of what they have and are able to do. It appeared that this stage of discovering their own power and strengths created a turning point in their lives.

Participants were also of the opinion that they had the frankness to share their deepest experiences and feelings in the group. They also felt that group members listened to each other, and recognised each other's strengths and assets. By applying this stage to their communities, they experienced successes. Participants further mentioned that the group members embraced diversity in the group. One response in this regard was: "Don't impose your values, but embrace the values of people". These findings correspond with the collective team approach of Freire (Grobler & Schenck, 2009; Rafi, 2003b; Roberts, 1996).

During the fourth stage of transformation, participants were enabled to mobilise their power and strengths which they had discovered during stage three. By becoming aware of their own strengths, feelings and power, they started taking control of their own lives and stopped others dictating to them. They therefore became more responsible, self-reliant and accountable for their own lives. They saw challenges and problems as opportunities to learn, change and develop. They became more assertive in their personal and professional lives, and their skills in communication and confidence improved. They started to believe that they have the power and strength to contribute to their own wellbeing. They had discovered that they could put their views across.

The participants responded: "Now I have learned to challenge each and every challenge and problem that I am facing"; "It help me to have this self-reliance and to really reflect on myself a lot and never allow myself to be invaded or oppressed by other people, and enabled me to break from the culture of silence"; "The challenges we are facing, they're actually there to train us"; "She made me aware that I am in control of my live"; and "I am more assertive and be able to confront other people".

These four stages correspond with the conscientisation process described by Freire and other authors, namely of creating an awareness of oppression, sharing this awareness with others, discovering their individual strengths and mobilising these strengths (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire 2008; Holman & Devane, 1999; Johnson, 2003; Micheletti, 2010; Schenck, 2002; Rafi, 2003a; Rafi, 2003b; Schenck et al, 2010).

Theme three: Transformation on a professional level

Being freed from a culture of silence, it appeared that participants have transformed from being either autocratic or passive leaders to more democratic leaders in both their personal and professional lives. Participants defined democratic leadership as having a voice and being able to put across one's own opinion, while recognising the opinions of others; allowing people to participate in discussions while valuing their input. The following responses were made in this regard: "You take other people's opinions into consideration when applying democratic leadership"; "People become more interdependent when applying democratic leadership"; and "I see how people freed themselves from the culture of silence by applying democratic leadership".

All participants were of the opinion that the most important skill of a democratic leader is that the views of all people involved have to be acknowledged before decisions are made in a collaborative manner. A participant commented, "You must make them to look at each other and let them all share their views before making a decision".

All the participants agreed that democratic leaders contributed to a liberated society. By practising a democratic leadership style, people became aware of their power and individual strength, and developed their own voice and identity. One response in this regard was: "I am coming up with new ideas and also help others to talk and to tell how they feel".

In general, participants found it difficult to change towards a democratic style but experienced positive results when it was applied. Most participants were either passive or autocratic leaders, but primarily passive leaders. However, since they applied a democratic leadership style, they have had better results in their personal and professional lives.

At the beginning of the training programme women were more passive leaders and men more authoritative in their approach as a result of their cultural habits and norms. A participant responded as follows: "Actually, most of the government leadership there's a lot of passive leadership, and that's why that we can't actually progress ... and even ... maybe in our personal lives most of us women had this passive leadership due to culture, and now we redirect our lives by saying no and tell people how we feel". The role that culture plays in the establishment of leadership styles was confirmed by the literature, namely men are inclined to be more authoritative and women more passive or laissez-faire leaders (Schultz, 2003; Zastrow, 2009).

A sub-theme that emerged was that democratic leaders should guide community members towards taking responsibility for their lives and trust them with tasks and opportunities. Some responses in this regard were the following: "We don't promise that we are going to do this (for the community), but we will be working along with you, but you are the people that are going to be achieving"; "You learn to deal with different people, different opinions"; "winning trust is something that is not easy"; "in order to work with a person you need to learn who they are and how they behave on tasks"; "Let's trust them with a task"; "Let them be part of it"; and "Give people opportunities, let them prove what they have".

Participants communicated that they also improved on their communication skills. They are more confident at work and have a stronger voice. They also encouraged people in the community to express their opinions. It is evident that the more people gain confidence, the more their communication skills improve (Blackburn, 2000; Homan, 2004; Swanepoel & De Beer, 2006; Weyers, 2011).

Participants were of the opinion that they were able to facilitate members in the community towards becoming aware of experiences of oppression. They also said that in working with people in the community, the weaknesses of facilitators should be discussed with community members, but these weaknesses should be used as strengths to assist others in getting hope. A response was: "Tell the people this is my situation and I'm willing to deal with it and I'm willing to move forward, not go back; use it as my strength, my power to do a lot of things out there". These findings correspond with those of Freire and are confirmed by other studies, which state that educators should share their experiences of oppression as well as their dreams with the people they are dealing (Blackburn, 2005; Erasmus-Kritzinger, Swart & Mona, 2000; Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire 2008; Micheletti, 2010; Rafi, 2003a; Rafi, 2003b).

In their work as community developers, they succeeded in embracing the culture and values of others and not imposing their values on them. Responses in this regard were: "You learn their culture and you understand how they live, and you allow the development to take place within the assets that are available"; and "It is the first time they sat down together and talked about their children."

As community developers, participants changed their views about poor and illiterate people. They realised that they should not look at poor and illiterate people as "empty vessels" for whom decisions have to be made by community developers. A response in this regard is: "They thought they could not think for themselves, but realised the strengths of these people".

These discoveries were also made in their work as community developers on a community level. Some responses in this regard were: "This module had a major impact ... a point where they become stable and they can sustain themselves"; and "It is very relevant to develop their consciousness that they can depend on themselves and stand up."

CONCLUSIONS

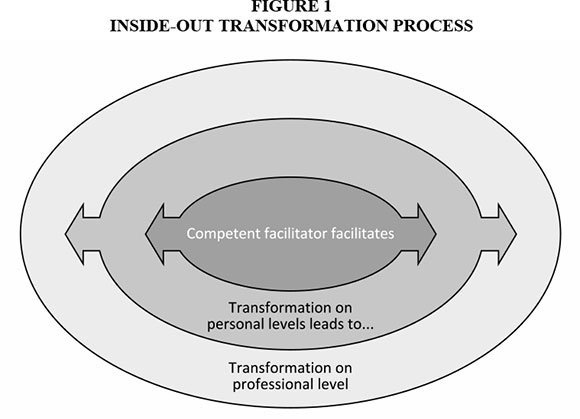

Practice guidelines derived from the findings are indicated in Figure 1. It is an inside-out process, starting with an experienced competent facilitator who guides people towards transformation on a personal level. Once a person becomes a liberated and transformed individual, he or she will be able to guide and facilitate people in communities to become transformed and liberated, which could only be done in a culturally sensitive way by applying a democratic leadership style.

A competent facilitator a prerequisite for the implementation of this personal leadership development model for community practice

Based on these findings it could be concluded that certain facilitation skills and characteristics are required for this model. A facilitator who not only knows the approach of Paulo Freire, but has integrated it into his/her life is a requirement. A facilitator who has been liberated and/or healed from oppression and is culturally sensitive is a further requirement. The authenticity of a facilitator and the ability to apply the principles and methods of Freire in the training process are important to break the culture of silence (Erasmus-Kritzinger et al., 2000; Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Micheletti, 2010; Quinn, 1982; Schenck et al., 2010).

Facilitators should be skilled in facilitation, where the relationship between the facilitator and participants is the most important ingredient in the process. The participants and facilitator are both educators and learners, and true facilitation is an active process of awareness and praxis that allows people to become truly engaged with their world. Facilitation should be done in a creative way applying various experiential, participatory methods, techniques and values linked with the culture and life world of participants. Facilitation should also be done in a relaxed atmosphere with confidentiality as the most important group rule. Honesty and trust should guide the process. The methodology has to be applied on a personal basis to students' lives first, before theory can be linked to the practical application of theory to practice in communities. Critical reflection on a regular basis is crucial for deep learning to take place. The facilitator's facilitation skills have to be well developed, the attitude and approach of the facilitator to all students have to be genuine; he/she must be approachable and be able to listen sincerely. These characteristics of effective teaching and learning have been confirmed by several researchers (Burkey, 1993; Chambers, 1983; Kaplan, 1996; Johnson & Johnson, 1994; Swanepoel & De Beer, 2006; Zastrow, 2009). It could be concluded that the end result of facilitation should be the development of the individual and involve an internal transformation process through which self-worth increases (Covey, 1992; Rahman, 1993; Schenck, 2002).

Transformation on a personal level as first step towards liberation

The transformation process should start on a personal basis before students will be successful in engendering it on a professional level. Based on the findings, it could be concluded that the facilitator should use the problem-posing method and not the banking method in education and training throughout the entire programme. He/she should act as a co-learner in the classroom in a collective way, allowing participants to develop a critical consciousness and become transformers of the world. The following four stages of transformation should be facilitated in the workshop to enable participants towards

- becoming aware of situations of oppression in their lives;

- sharing these situations with each other;

- discovering their own unique strengths and values; and

- taking ownership of their own lives and becoming self-reliant and responsible.

These steps correspond with Freire's conscientisation process, which should be facilitated through a continuous process of action-reflection-action (Freire, 1994; Freire, 2004; Freire, 2008; Rafi, 2003a; Rafi, 2003b; Schenck, 2002). Freire's philosophy, principles and process should be applied throughout the process.

Transformation on a professional level as second step towards liberation

It is evident from the study that only when transformation has taken place on a personal level is it more likely that it will occur on a professional level. It is also evident that the most appropriate leadership style which complemented Freire's approach is a democratic leadership style. Democratic leaders seek the maximum involvement and participation of every member in all decisions affecting the group and attempt to spread responsibility rather than concentrate it (Adair, 2008; Manning & Curtis, 2003; Zastrow, 2009).

LIMITATIONS OF STUDY

The findings could only be generalised among the research population, namely the 22 participants who formed part of the entire class and could not be generalised to the bigger community. Although emphasis was placed in the interviews on the effect of Freire's approach on their personal and professional lives, the results could be contaminated by other modules of the certificate programme.

A CONCLUDING NOTE

If training programmes in community practice, which are based on Paulo Freire's pedagogy of the oppressed, are implemented in a participatory, experiential, collective way with a focus on awareness raising of feelings and memories of past experiences of oppression, discrimination, segregation and rejection, participants could break through the culture of silence and become healed and transformed on a personal level. It is also crucial that for students to be able to make a difference in community members' lives, they themselves have to be healed, liberated and transformed on a personal basis. A competent facilitator is another requirement for the success of such a programme. Facilitators who apply Freire's methodology should be trained to apply theory in an experiential participatory way.

REFERENCES

ADAIR, J.K. 2008. Everywhere in life there are numbers. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5):408-415. [ Links ]

AFFOLTER, F.W., RICHTER, K., AFAQ, K., DAUDZAI, A., MASSOOD, M.T., RAHIMI, N. & SAHEBIAN, G. 2009. Transformative learning and mind-change in rural Afghanistan. Development in Practice, 19(3):311-328. [ Links ]

BARNES, M.D. & FAIRBANKS, J. 1997. Problem-based strategies promoting transformation: implication for the community health worker model. Family and Community Health, 20(1):54-65. [ Links ]

BARTLETT, L. 2005. "Dialogue, knowledge, and teacher-student relations: Freirian pedagogy in theory and practice." Comparative Education Review, 49(3):3-17. [ Links ]

BLACKBURN, J. 2000. Understanding Paulo Freire: reflections on the origins, concepts, and possible pitfalls of his educational approach. Community Development Journal, 35(1):3-15. [ Links ]

BRIGHAM, T.M. 1977. Liberation in social work education: applications from Paulo Freire. Journal of Education for Social Work, 13(3):5-11. [ Links ]

BRUEGGEMANN, W.G. 2006. The practice of macro social work (3rd ed). Australia: Thomson/Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

BURKEY, S. 1993. People first; a guide to self-reliant, participatory, rural appraisal. New Jersey, USA: Zed Books. [ Links ]

BURSTOW, B. 1991. Freirian codifications and social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 27(2):196-207. [ Links ]

CHAMBERS, R. 1983. Rural Development, putting the last first. Essex, England: Longman Scientific and Technical. [ Links ]

COVEY, S.R. 1992. The seven habits of highly effective people: powerful lessons in personal change. London: Simon and Schuster Ltd. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 1998. Qualitative inquiry and research design. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

DAFT, R.L. & MARCIC, D. 2004. Understanding management (4th ed). Australia: Thomson. [ Links ]

DELPORT, C.S.L. & DE VOS, A.S. 2011. Professional research and professional practice. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. Research at grass roots, for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

DELPORT, C.S.L., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & SCHURINK, W. 2011. Theory and literature in qualitative research. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. Research at grass roots, for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

DREYER, J.M. 2000. Onderwysersopleiding vir uitkomste-gebaseerde onderwys in Suid-Afrika (translated title: Training of teachers for outcome based education in South Africa). Pretoria: Unisa. (D Ed thesis) [ Links ]

ERASMUS -KRITZINGER, L., SWART, M. & MONA, V. 2000. Advanced communication skills for organizational success. Pretoria: Afritech. [ Links ]

FINLAY, L.S. & FAITH, V. 1980. Illiteracy and alienation in American colleges: is Paulo Freire's pedagogy relevant? The Radical Teacher, 22(16):28-37. [ Links ]

FOOTE, M. 2010. Creating a community of support for graduate students and early career academics. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 34(1):7-19. [ Links ]

FREEDMAN, E.B. 2007. Is teaching for social justice undemocratic? Harvard Educational Review, 77(4):442-473. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. 1994. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. 2004. Pedagogy of hope. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. 2008. Education for critical consciousness. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

GRBICH, C. 2007. Qualitative data analysis: an introduction. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GREEN, D. 2008. From poverty to power, how active citizens and effective states can change the world. Sunnyside: Oxfam International. [ Links ]

GROBLER, H.D. & SCHENCK, C.J. 2009. Person-centred facilitation: process, theory and practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HENDERSON, P. & THOMAS, D.N. 2002. Skills in neighbourhood work. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

HENNING, E. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

HOLMAN, P. & DEVANE, T. 1999. The change handbook, group methods for shaping the future. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

HOMAN, M.S. 2004. Promoting community change, making it happen in the real world (3rd ed). Australia: Thomson, Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

HOPE, A. & TIMMEL, S. 1995. Training for transformation; a handbook for community workers, Book 1-3. London, Great Britain: ITDG Publishing. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, D.W. 2003. Reaching out: interpersonal effectiveness and self-actualization (8th ed). USA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, D.W. & JOHNSON, F.P. 1994. Joining together, group theory and group skills (5th ed). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

KAPLAN, A. 1996. The development practitioner's handbook. London, England: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

KIDD, R. & KUMAR, K. 1981. Co-opting Freire: a critical analysis of pseudo-Freirean adult education. Economic and Political Weekly, 16(1/2):27-29,31,33,35-36. [ Links ]

KORTEN, D. 1990. Getting to the 21st century. West Hartford: Kumanian Press. [ Links ]

KRAJEWSKI, D., LOCKWOOD, J., KRAJEWSKI-JAIME, E.R. & WIENCEK, P. 2011. University and community partnerships: a model of social work practice. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 6(1):39-47. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.SocialSciences-JOurnal.com,ISSN 1833-1882.

KRETZMANN, J.P. & McKNIGHT, J.L. 1993. Building communities from the inside out. Evanston: Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research, Neigborhood Innovations Network, Northwestern University. [ Links ]

LAIRD, D. 1985. Approaches to training and development. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. [ Links ]

LINCOLN, Y.S. & GUBA, E.G. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

MANNING, G. & CURTIS, K. 2003. The art of leadership. Boston: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

MATHESON, C. & MATHESON, D. 2008. Community development: Freire and Grameen in the Barrowfield project, Glasgow, Scotland. Development in Practice, 18(1):30-39. [ Links ]

MAX-NEEF, M. 1991. Human scale development; conception, application and further reflections. New York, USA: The Apex Press. [ Links ]

MICHELETTI, G. 2010. Re-envisioning Paulo Freire's "Banking Concept of education". [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.studentpulse.com/articles/171/re-envision-ing-paulo-freieres-banking-concept. [Retrieved: 10/06/2011].

MOCOMBE, P.C. 2005. Where did Freire go wrong? Pedagogy in globalization: the Grenadian example. Race, Gender and Class, 12(2):178-199. [ Links ]

MOSOETSA, S, 2011. Eating from one pot; the dynamics of survival in poor South African households. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

NELSON-JONES, R. 1991. Lifeskills, a handbook. London: Cassell. [ Links ]

NHLANHLA, H.A.Z. 2010. Towards improved praxis: a case study of the certificate in education (participatory development). Durban: KwaZulu-Natal University. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

NTAKIRUTIMANA, E. 2010. A Christian development appraisal of the Ubunye Cooperative Housing initiative in Pietermaritzburg. Durban: KwaZulu-Natal University. (Doctoral thesis in Theology) [ Links ]

NYEBERAH, M.P. 2010. Entrepreneurship and freedom: a social theological reflection on the church and small business in Zimbabwe. Durban: KwaZulu-Natal University. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

QUINN, P. 1982. Education and the transformation of society. The Crane Bag, 32(2):53-57. [ Links ]

RAFI, M. 2003a. Farwell Freire? Conscientisation in early twenty-first century Bangladesh. Convergence, XXXVI(1):41-61. [ Links ]

RAFI, M. 2003b. Freire and experiments in conscientisation in a Bangladesh village. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(37):3908-3914. [ Links ]

RAHMAN, M.A. 1993. People's self-development: perspectives on participatory action research. London: Zed. [ Links ]

Roberts, P. 1996. Structure, direction and rigour in liberating education. Oxford Review of Education, 22(3):295-316. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, C.J. 2002. Revisiting Paulo Freire as theoretical base for participatory practices for social workers. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 31(1):71-80. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, R., NEL, H. & LOUW, H. 2010. Introduction to participatory community practice. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

SCHULTZ, H. (ed). 2003. Organisational behaviour, a contemporary South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publications. [ Links ]

SINGER, E. & SHOPE, J.H. 2000. Women, speak with a loud voice! International Feminist Journal of Politics, 2(1):82-101. [ Links ]

STRYDOM, H. & DELPORT, C.S.L. 2011. Qualitative research designs. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHÉ, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. Research at grass roots, for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

SWANEPOEL, F. & DE BEER, F. 2006. Community development; breaking the cycle of poverty. Landsdowne, RSA: Juta. [ Links ]

THERON, P.F. 1993. Theological training in the context of Africa: a Freirean model for social transformation as part of the missionary calling of the church. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (Doctoral thesis) [ Links ]

TOSELAND, R.W. & RIVAS, R.F. 2005. An introduction to group work practice (5th ed). Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

WEYERS, M.L. 2011. The theory and practice of community work: a South African perspective (2nd ed). Potchefstroom, South Africa: Keurkopie. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, L. 2004. Culture and community development: towards new conceptualizations and practice. Community Development Journal, 39(4):345-359. [ Links ]

ZASTROW, C.H. 2009. Social work with groups (7th ed). USA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]