Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 no.1 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-20

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-20

A conceptual analysis of the label "street children": Challenges for the helping professions

Mankwane Makofane

Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Societies are judged by the way they treat their children. This treatment can include the way that societies label or categorise children, an aspect that is particularly salient in relation to children who live on the streets (Panter-Brick, 2003:152; Ribeiro, 2008:90). The power of the spoken word has the potential to stigmatise, dehumanise and demean such children if they are referred to in a negative manner. For instance, stigmatising beliefs are "unjustified negative things people believe about others that involve a moral judgement" (Deacon, 2006:419). The argument of this paper is thus based on the African dictum Leina lebe seromo, which is akin to the maxim "Give a dog a bad name and hang him". It is against this background that the negative portrayal of these children is attributed to the use of the label "street children" in the South African context.

The presentation is inspired by the information obtained from the 2011 fourth-level student social workers' research reports based on a qualitative study of "street children"1. The 37 reports, which obtained marks of 60% and higher, painted a grim picture of the views expressed by the children regarding the reaction of the public towards them. Some of the children attributed the public's negative attitudes towards them to the label "street children".

Children who were living on the streets indicated to the students that most children of all races shunned them, while others appeared to be scared of them. It was also reported that parents pulled their own children closer to them when they encountered children who lived on the streets.

Such reactions caused children who live on the streets to feel unaccepted by some people. In some instances the general public blamed them for petty theft, sniffing glue and abusing alcohol. It has also been noted from previous studies that many people perceive these children as deviants involved in substance abuse (Mufune, 2000:241-42), while others regard them as "a social menace" (Ribeiro, 2008:90). Children who were living on the streets were verbally insulted by some adults in the presence of their children. Their plight is evinced by the following statements from the research conducted by the students:

"The general public is unfair towards us; they regard us as street kids and a danger to society. They also label us 'thieves ', 'dagga smokers ', 'glue sniffers ' and 'alcohol abusers ', while they have no idea who we are."

"It is painful to be called 'a street kid' when we are not responsible for our situations. Yes, some of the children ran away from home, but others like me are orphans and our relatives are not prepared to live with us."

The voices of the children on this matter are loud and clear. The findings confirm findings from many studies indicating that members of the public have negative perceptions of children who live on the streets and implicate them in various acts of deviance (Chetty, 1997:50; Mufune, 2000:240). The children also felt stigmatised. Stigma in this context should be understood "as a problem of fear and blame" (Deacon, Stephney & Prosalendis, 2005:x).

The research reports provided a broad spectrum of findings, especially with regard to the pain endured by the children as a result of the public's negative attitude towards them. However, the question to be asked is whether the stigmatisation is due to the use of the label "street children" or due to the public's negative reaction towards these children? This is a critical area that requires further in-depth investigation. The information obtained, disconcerting as it was, demonstrates and confirms the resilience of these children as illustrated by several authors (Boyden & Mann, 2005; Henry, 2001; Schimmel, 2006) and inspired an extensive literature review on the concept "street children".

Overall, these findings confirm those of the national study on the living conditions of "street children" conducted by the Gauteng Alliance for Street Children (GASC, South Africa) in 2005, which found that 62% of the children did not like to be called "street children" (Roestenburg, 2010:243).

PROBLEM STATEMENT

There is no commonly agreed definition of street children (Else, 2006:192). For instance, researchers and organisations who work on this issue hold different views on what exactly the concept "street children" defines (Iqbal, 2008:201). It should be borne in mind that the label "street children" was originally adopted by international agencies to avoid negative overtones for children who had been known as vagrants, rag-pickers and glue-sniffers (Panter-Brick, 2003:151). These labels are used to distinguish children living on the streets from those living at home. Labels are influenced by people's perceptions based on the activities of the children. However, the public's generalisations when referring to children who live on the streets may be misleading, especially when it is noted that some of the literature presents the ability of these children to endure adversity and to become responsible citizens (Henry, 2001; Boyden & Mann, 2005).

The normalisation of society's marginalisation of vulnerable children is likely to make affected children feel unwanted. The helping professions such as social work, psychology and theology, to mention a few, may also fail to realise the negative influence such a label may have on their initiative to develop relevant multidisciplinary intervention programmes to alleviate the affected children's social, economic, psychological, educational and spiritual problems.

The National Department of Social Development has a strategy and guidelines for children living and working in the streets. However, the label that is commonly used, i.e. "street children", was not subjected to scrutiny by researchers, practitioners and the children regarding its implication for those affected. Nevertheless, some researchers endeavoured to show how negative connotations of the use of the designation have been ignored (Hecht, 1998; Hutz & Koller, 1999; Panter-Brick, 2003). According to Dallape (1996:283), renowned for many years of experience with African children living and working in the street, the term "street children" is "inappropriate, offensive and gives a distorted message". Some of the implications of the use of the designation "street children" for practice are encapsulated in De Moura's (2002:363) assertion that the social constructions of street children are not harmless, since "they influence policy and interventions from governmental and non-governmental organisations, which in turn help to perpetuate the status quo of social inequality". There is confusion and contradiction in the use of the label "street children", as discussed below.

Murithi (2007:277) warns about the lack of participation by certain countries in the development of human rights by pointing out that "[w]hat is true is that the current international human rights standards, beginning with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, were not developed through a global, broad-based consultation of the different values from around the world". The same could be said about the label "street children", adopted by the South African helping professions without considering its implications for the affected children.

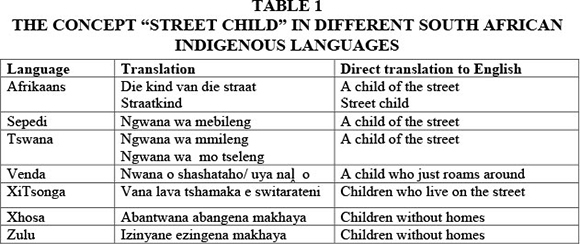

Even though the concept "street children" has been adopted by international agencies (Panter-Brick, 2003:151), Mufune (2000:235) asserts that Africa has diverse languages and cultures, and hence using "the conception of 'street youth' is akin to imposing assumptions from a distinct environment and imputing a false cultural homogeneity on Africa". This view resonates with that of the present author. Table 1 below presents the meanings of the term "street child" in a number of different South African indigenous languages, with a direct translation in English in each case to show the difficulty of using the term in the South African context.

The first reaction of 21 people (three per language), colleagues and older persons consulted to provide the meaning of "street children" in their mother tongue was intriguing. They all said that the concept is foreign, since culturally children in adversity were taken care of by their relatives. However, they acknowledged that they became aware of the phenomenon after observing with concern children sleeping on pavements and under bridges. This then led different ethnic groups to formulate descriptive terms for such children. Lack of agreement among people from the same ethnic group on the correct translation has been noted. However, a high degree of convergence was observed on the view that explanations provided in indigenous languages do not capture the essence of the meaning of "street children".

The lack of an international agreed-upon definition of the term "street children" creates an opportunity for a diverse South African society to engage rigorously on this matter. This article seeks to provide a literature review to highlight the contradictions and confusion emanating from various definitions of the term "street children" as illustrated below. The intention of this paper is to open a conversation with readers across the board to critically discuss the construct "street child" in the South African context.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section focuses on the literature that defines, explains and describes the notion of "street children" to demonstrate the difficulty of the use of the label in practice because of its negative connotations.

Since there is no universal definition of "street children", broad and ambiguous definitions are subject to several interpretations (Benitez, 2003:107; De Moura, 2002:355). In some cases the terms used to refer to children living on the streets vary according to the geographical area of their home country (De Moura, 2002:354). Research studies in North America and Western Europe use the term "homeless" interchangeably with "street children", while countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America use the term "street children" (De Moura, 2002:354; Le Roux & Smith, 1998:2).

Researchers and organisations working with children who live on the streets hold different opinions on what the concept of street children delineates. For instance, pertinent questions raised relate to whether the term refers to those who work and/or spend days and nights outside their homes, or to those who return to their homes after spending the whole day on the streets (Iqbal, 2008:201).

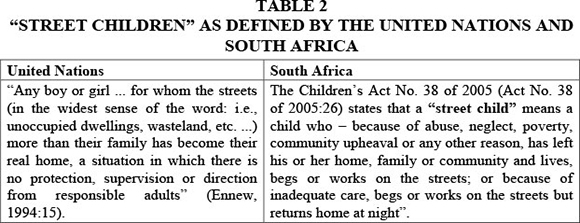

Some definitions of children who live on the streets accentuate their negative characteristics in an attempt to distinguish them from other children. For example, Cosgrove (1990:192) states that "[a] street child is any individual under the age of eighteen whose behaviour is predominantly at variance with community norms, and whose primary support for his/her development needs is not a family or family substitute". Such an assertion probably led to Le Roux and Smith (1998:1) raising the question of whether the street child phenomenon is synonymous with deviant behaviour. The authors made an attempt to answer the question through an analysis of various definitions of street children used in the 1980s and early 1990s, which led to the conclusion that "[h]ighly charged reactions to street children make it difficult to remain objective" (Le Roux & Smith, 1998:3). Table 2 below provides the definitions of "street children" as presented by the United Nations and by the South African government.

A juxtaposition of the description of "street children" provided by the United Nations (cited by Ennew, 1994:15) and the South African Children's Act (Act No. 38 of 2005), reveals a clear distinction between the definitions. The South African government acknowledges circumstances or adversity that may compel children to leave their homes to seek refuge in the street. Conversely, the definition offered by the United Nations (cited by Ennew, 1994:15) focuses more on the place of abode for the children who live on the streets and lack parental or adult supervision, and does not take into account conditions that could have led children to opt to leave their homes for the streets.

The term "children of the street" refers to those who live on the streets without adult supervision, while "children on the street" refers to those who beg and do menial work on the streets and return home to contribute towards their families' livelihood (Richter, 1988:7; 1991:5). Subsequently, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) included another category, namely "children at risk". This phrase refers mostly to poor children from urban areas who may end up living and working on the streets (UNICEF, 2005) and are at risk of abusing substances as well as long-term risks such as lack of education.

On the other hand, Iqbal (2008:201) regards the definition by West as comprehensive, as it states that the label "street children" is "a shorthand for children who transit to the streets - children who work on the street, or children who live on the street, with a variety of occupations, including beggars, garbage pickers, shoeshine boys, flower sellers, sweet shop workers, commercial sex workers and petty criminals". However, the challenge with regard to this definition is that most people are unlikely to know that the label is a shortened version of children living and/or working on the streets.

The author is of the view that some people may have reservations about using the term "street children" because of its emotional nuances. In a diverse society such as the South African one, it is to be expected that individuals will attach different meanings to the term based on their socio-cultural backgrounds and language as depicted in Table 1. Some may find it appropriate and acceptable, while others may find it inappropriate, offensive, derogatory, dehumanising and/or perpetuating the social exclusion of children in adversity through stigmatisation.

Pare (2003:21) proposes that the term could be replaced with "a more socially acceptable term, such as autonomous homeless children". Of concern in this instance, though, is the usage of the concept "autonomous", considering that children require protection and guidance from parents or guardians. Schimmel (2006:211) suggests the use of the term "street-living children" because he regards it as "unambiguous and self-explanatory and therefore appropriate to use to refer to children living in the street without parental care or supervision".

From the literature reviewed it seems that the limitations in the use of the label "street children" as a working concept relate to the fact that it refers to a place of abode and the absence of proper care by adults from a family home and in society (Panter-Brick, 2003:148). It fails to recognise that children work in the street, dance in the street, beg in the street and sleep in the street, "but the street is the venue for their actions not the essence of their character" (Hecht, 1998:103).

Furthermore, the label is used to categorise and pigeonhole children living on the streets (Hanschur, 2009:1) and fails to acknowledge their different characteristics such as gender and activities (Dallape cited in Pare, 2003:21), as well as family characteristics such as life histories and prognoses (Hutz & Koller, 1999:60; Pare, 2003:2). Ennew (2000:171) is of the view that the category of street children may be "impossibly constructed".

Raffaelli and Larson (1999:1) postulate that the label is not reliable as it conceals variations in the experiences of children who share the common condition of being in the street, spending their lives outside the spheres considered appropriate for children, such as home, school and recreational settings. On the other hand, Panter-Brick (2003:151) regards the use of the label "street children" as emotionally charged and does little to serve the interests of the children in question; it has a stigmatising effect as children are assigned to the streets and to delinquent behaviour. Moreover, Panter-Brick (2003:150) asserts that researchers and organisations providing services to these children find it difficult to uphold the typology of children "of the street" (those who have access to their families but make the streets their home) and "on the street" (those who return at night to their families) established by UNICEF to differentiate street-based or home-based street children.

It is important to note that once a person has been given a label, the person becomes defined by it and consequently the entire person's experiences, feelings and desires become defined in terms of the label (Saleebey, 1997:5). Hence, Egan (1998:77) cautions that those in the helping professions "forget at times that their labels are interpretations rather than understandings of the client's experience".

The phenomenon of "labelling" can be partly explained in terms of the so-called theory of "othering". Sociologists and philosophers have developed a theory of "othering" to describe the processes whereby people who are different from us become increasingly alien and distanced from us (Cromer, 2001:192). Furthermore, this distancing leads to the emergence of a dividing wall of hostility and suspicion between the insider and the outsider, with those on the outside being perceived as "others" and less wanted than "insiders" (Cromer, 2001:192). Some theorists thus regard "othering" as a key dynamic underlying stigma (Deacon et al., 2005:38). Stigma is defined by Goffman (cited in Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995:304) as "a powerful discrediting and tainting social label" changes the way individuals are viewed as persons. The label "street children" h as the potential of causing these children to be subject to "othering". In an effort to avoid the labelling effects of the concept "street children", Roestenburg (2010:243) opted for the use of "children in street situation".

The existence of the phenomenon is indisputable. However, the understanding of the matter has been confused by diverse definitions of "street children" having been provided for it by researchers, scholars and global organisations. According to many definitions, the street is not viewed as a temporary place of residence while the children explore other options, or await someone such as a concerned and good citizen or social workers, child and youth care workers and religious leaders to rescue them from living on the streets.

DISCUSSION

The goal of studying the definitions of the concept "street children" was to highlight its different meanings. The goal was accomplished through the presentation of different explanations of the concept "street children" that are influenced by the authors' contexts. In South Africa, besides the definition of "street children" provided by the Children's Act (Act No. 38 of 2005), during the past ten years, Roestenburg (2010:243) seems to be the only South African researcher who has attempted to provide a neutral definition for the concept. The neutrality of the term "children in street situation" (Roestenburg, 2010:243) lies in the context in which children find themselves.

Caution must be exercised in the selection of a definition of "street children", as so me definitions may lead people to discriminate and stigmatise these children advertently or inadvertently. It is therefore vital to bear in mind that people's understanding of reality is influenced by their social, cultural and historical background (Hanschur, 2009:1). The actual question is: Whose lens do South Africans use to acquire an in-depth understanding of the understanding of the phenomenon of children living on the streets?

In order to address the social construction of this frequently used label, there is a need for a public discourse among professionals, affected children and interested groups about the use of the term "street children" in South Africa. For instance, in African cultures there are still values such as ubuntu relating to how "humanity is achieved through others" (Ramose, 2010:300) that should be utilised for the promotion of children's rights and for interrogating terms such as "street children". Such a platform will create a climate for affected children to articulate their views on the matter. Most importantly, for progressive development to occur, children's views should be respected in matters concerning them (Bray, 2002:43-44; Chama, 2008:414; Panter-Brick, 2003:157; UNICEF, 2009:9).

Mamphiswana and Noyoo (2000:27) claim that "[i]n a diverse country like South Africa with a long history of both racial and ethnic divisions, social work practitioners should be prepared for anti-discriminatory social work practice". Consequently, social work education in South Africa should consider incorporating practice models in the curriculum that promote children's and human rights in such a way that prospective social workers will be assisted in becoming more culturally sensitive in a diverse society. However, the transition may not be easy for some educators, because the thinking of most modern African educators and educationists has already become infused with Western-style theories of education (Van der Walt, 2010:260). Therefore, it is important to develop a purpose-made solution by taking aspects from each approach and developing a solution to the challenge in the spirit of ubuntu.

Different countries and communities have different life experiences, interpretations and expectations and consequently joint deliberations and actions are most meaningful in the context in which they are generated (De Moura, 2002:364). The classification of children on the streets is most often undertaken for the convenience of policy makers, researchers, statisticians and service providers charged with the responsibility of designing appropriate programmes that would safeguard the children's rights and enhance their development cognitively, socially, psychologically and emotionally. Unfortunately, such classification does not benefit vulnerable children who live on the streets. For instance, De Moura (2002:354) asserts that the social construction of children living on the streets "invites or guides certain kinds of interventions at the expense of others".

CHALLENGES FOR THE HELPING PROFESSIONS

The agreed upon non-stigmatising label for children who live on the street is critical considering that the social exclusion of such children is likely to perpetuate the professionals' and communities' reactionary short-term responses. In line with inter- and multidisciplinary research, it is vital for the helping professionals (academics and practitioners) to join forces in initiating multidisciplinary teams that would develop and implement long-term sustainable interventions to assist children in adversity after a consensus has been reached on the appropriate term to use to refer to children who live on the streets. Such a concerted effort will lead to relevant and effective responses to the affected children.

Suggested conversations among all role players to explore the meaning of the label "street children" in the South African context should be guided by societal values. Research endeavours could be accomplished through fostering collaboration between government and institutions of higher learning. The public should be encouraged to participate in the process of reconceptualisation that would demonstrate the interconnectedness among all members of society. This was the case with the previous label "handicapped" persons, who were subsequently referred to as the "disabled" and now "people with disabilities" (Pare, 2003:22) or "persons with physical disabilities" in South Africa. Public engagement could be facilitated by social workers and religious leaders through reflexive exercises in workshops, seminars and conferences to serve as groundwork for charting a better future for children who have been living outside of mainstream society. Issues related to stigmatisation and stereotypes of children who live on the streets should be addressed; otherwise the use of negative labelling will remain a challenge to the helping professionals until initiatives are taken to address it properly.

CONCLUSION

The children who live on the streets are not comfortable being called "street children" (GASC, South Africa cited by Roestenburg, 2010:243). Social workers are mandated to promote children's rights and to protect them against any form of violation. Therefore, to bring healing to the affected children, social workers in collaboration with religious leaders and communities should lead in the creation of constructs that would promote rights-based anti-discriminatory practice for these children in terms of the philosophy and principles of ubuntu.

REFERENCES

ALONZO, A.A. & REYNOLDS, N.R. 1995. Stigma, HIV and AIDS: an explanation and elaboration of a stigma trajectory. Social Science & Medicine, 41(3):303-315. [ Links ]

BENITEZ, ST. 2003. Approaches to reducing poverty and conflict in an urban age: the ease of homeless children, youth explosion in developing world cities. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.wilsoncentre.org. [Accessed: 12/09/2011].

BOYDEN, J. & MANN, G. 2005. Children's risk, resilience, and coping in extreme situations. In: UNGAR, M. (ed) Handbook for working with children and youth: pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

BRAY, R. 2002. Missing links? An examination of contributions made by social surveys to our understanding of child well-being in South Africa. CSSR Working Paper No, 23. Centre for Social Sciences Research, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

CHAMA, S.B. 2008. The problem of African orphans and street children affected by HIV/AIDS: making choices between community-based and institutional care practices. International Social Work, 51(3):410-415. [ Links ]

CHETTY, V.R. 1997. Street children in Durban: an exploratory investigation. Pretoria: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

COSGROVE, J. 1990. Towards a working definition of street children. International Social Work, 33:185-192. [ Links ]

CROMER, G. 2001. Amalek as other, other as Amalek: interpreting a violent biblical narrative. Qualitative Sociology, 24(2):191-202. [ Links ]

CSC panel discussions: promoting and protecting the rights of street children. 2001. UN General Assembly Special Session on Children. Third PrepCom. NY. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.streetchildren.org.uk/uploads/Publications/334.promotingprotectingrights of children.

DALLAPE, F. 1996. Urban children: a challenge and an opportunity. Childhood, 3(2):283-294. [ Links ]

DEACON, H. 2006. Towards a sustainable theory of health-related stigma: Lessons from the HIV/AIDS literature. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16:418-425. [ Links ]

DEACON, H., STEPHNEY, I. & PROSALENDIS, S. 2005. Understanding HIV/AIDS stigma: a theoretical and methodological analysis. Pretoria, South Africa: Human Science Research Council Press. [ Links ]

DE MOURA, S.L. 2002. The social construction of street children: configuration and implications. British Journal of Social Work, 32(3):353-368. [ Links ]

EGAN, G. 1998. The skilled helper: a problem-management approach to helping (6th ed). Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cle Publishing Company. [ Links ]

ELSE, 0. 2006. Poverty: an international glossary. CROP international studies in poverty research. London: Zed Books Ltd. [ Links ]

ENNEW, J. 1994. Street and working children: a guide to planning. Save the Children, London. [ Links ]

ENNEW, J. 2000. Why the Convention is not about street children. In: FOTTRELL, D. (ed) Revisiting Children's Rights. 10 Years of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Hague/Boston: Kluwer Law International. [ Links ]

GRINNELL, R.M. & UNRAU, Y.A. (eds). 2011. Social work research and evaluation (9th ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HANSCHUR, J.B. 2009. Participation in research - street children in Accra, Ghana. Paper to children's citizenship and participation rights - accessibility and exclusion (CCPR). [ Links ]

HECHT, T. 1998. At home in the street: street children of Northeast Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HENRY, D.L. 2001. Resilient children: what they tell us about coping with maltreatment. Social Work in Health Care, 34(3/4):283-298. [ Links ]

HUTZ, C.S. & KOLLER, S.H. 1999. Methodological and ethical issues in research with street children. New Directions for Child Adolescent, 85(Fall): 59-70. [ Links ]

IQBAL, M.W. 2008. Street children: an overlooked issue in Pakistan. Child Abuse Review, 17:201-209. [ Links ]

KOLLER, S.H., HUTZ, C.S. & SILVA, M. 1996. Subjective well-being of Brazilian street children. Paper presented at XXVI International Congress of Psychology (June), Montreal, Canada. [ Links ]

LE ROUX, J. & SMITH, C.S. 1998. Is the street child phenomenon synonymous with deviant behaviour? Adolescence, 33(132):1-9. [ Links ]

MAMPHISWANA, D. & NOYOO, N. 2000. Social work education in a changing sociopolitical and economic dispensation: Perspectives from South Africa. International Social Work, 43(1):21-32. [ Links ]

MUFUNE, P. 2000. Street children in Southern Africa. International Social Science Journal, 52(2):233-243. [ Links ]

MURITHI, T. 2007. A local response to the global human rights: the ubuntu perspective on human dignity. Globalisation, Sciences and Education, 5(3):277-286. [ Links ]

PANTER-BRICK, C. 2003. Street children, human rights, and public health: a critique and future directions. Children, Youth and Environments, 13(1):147-171. [ Links ]

PARE, M. 2003. Why have street children disappeared? - The role of international human rights law in protecting vulnerable groups. The International Journal of Children's Rights, 11:1-32. [ Links ]

RAFFAELLI, M. & LARSON, R. (eds). 1999. Homeless and working youth around the world: exploring developmental issues. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

RAMOSE, M.B. 2010. The death of democracy and the resurrection of timocracy. Journal of Moral Education, 39(3):296-303. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, M.O. 2008. Street children and their relationship with the police. International Nursing Review, 55:89-96. [ Links ]

RICHTER, L.M. 1988. Children living and working in the street of Africa. A paper presented at the children living and working in the street Initiative International Conference, April 13-14, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

RICHTER, L.M. 1991. Street children in South Africa: street children in rich and poor countries. The Child Care Worker, 9(9):5-7. [ Links ]

ROESTENBURG, W.J.H. 2010. A South African perspective on children in street situation. In: LIEBEL, M. & LUTZ, R. (Hrsg), Sozialarbeit des Sudens Band 3 -Kindheiten und Kinderrechte. Oldenburg: Paulo Freire Verlag, 241-257. [ Links ]

RSA (Republic of South Africa) 2005. South African Children's Act No. 38 of 2005. Government Gazette, No. 28944. South Africa. [ Links ]

SALEEBEY, D. 1997. The strengths perspective in social work practice. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

SCHIMMEL, N. 2006. Freedom and autonomy of street children. International Journal of Children's Rights 14(3):211-234. [ Links ]

UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund). 2005. The state of the world's children: excluded and invisible. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.unicef.org/sow06/profiles.ph. [Accessed: 12/09/2011].

UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund). 2009. Annual report. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.unicef.org/publications/file/UNICEFAnnual Report 2009. [Accessed: 15/04/2012].

VAN DER WALT, J.L. 2010. Ubuntugogy for the 21st century. Journal of Third World Studies, 27(2):249-266. [ Links ]