Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Social Work

versão On-line ISSN 2312-7198

versão impressa ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 no.1 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-19

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-19

Patterns of contact and involvement between adolescents and their non-resident fathers

Estelle de Wit; Dap Louw; Anet Louw

Department of Psychology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Divorce has become increasingly prevalent worldwide, and in 2012 it was estimated that nearly 50% of first marriages in the United States (USA) ended in divorce (American Psychological Association, 2012). In South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2010), 30 763 divorces were granted in 2009. Mostly women filed for divorce, with 55.8% of divorce applications emanating from the white population group, while African women comprised 41.3% of the group filing for divorce. The statistics also indicate that in 2009 the number of children under the age of 18 years who were affected by divorce numbered 28 295. International trends indicate that mothers continue to seek sole physical custody1 and are successful 80-85% of the time, whereas only 10-15% of fathers have sole physical custody (Cheadle, Amato & King, 2010; Emery, 1994; Kelly, 2007). Regardless of whether fathers have played an active parental role prior to divorce, it is generally accepted that parents and courts alike commonly adopt an access arrangement after divorce in terms of which children reside primarily with their mothers and spend some weekends and school holidays with their fathers (Kelly, 2007; Louw, 2010). Implicit in these residential arrangements is the potential to relegate the role of the father to that of a "visiting parent" (Kelly, 2007:38) and maintenance provider, and to marginalise the father-child relationship (Fabricius & Braver, 2003; Finley, 2006).

Fathering after divorce represents relatively "uncharted territory" (Palkovitz & Palm, 2009:3), and there is growing concern that the practice of post-divorce fathering and especially research in this area have not kept up with the rhetoric surrounding it, resulting in "extensive ambiguity and confusion" (Hawthorne & Lennings, 2008:191). Therefore, this study was conceived to examine the present reality in respect of the patterns of contact and the extent of involvement of fathers after divorce. An investigation into these aspects is useful not only at a practical level for parents and professionals alike in providing assistance in relation to the structuring of visitation arrangements after separation, but also to address gaps in existing knowledge regarding the way in which fathering may be changing and evolving after divorce. Also, the many complex issues regarding the restructuring of one family unit into two stable functioning units deserve adequate exploration to address the structural and psychological processes at work in families affected by divorce (Dyer, Jini, Mupedziswa & Day, 2011; Goncy & Van Dulmen, 2010; Kelly, 2007).

The frequency of contact between non-resident fathers2 and their children continues to be a subject of much scholarly debate (Holmes & Huston, 2010; Juby, Billette, Laplance & Le Bourdais, 2007; Sobolewski & King, 2005), as research regarding the actual amount of time that children spend with their fathers is very limited and difficult to obtain (Kelly, 2007). Furthermore, no reliable measures to accurately record the numerous complexities and variations in contact patterns are currently in use (Holmes & Huston, 2010). Post-divorce contact between non-resident fathers and their children are defined mostly along dimensions such as frequency, regularity, continuity and direct (face-to-face) or indirect (communication by telephone/e-mail/letter) contact (Dunn, Cheng, O'Connor & Bridges, 2004).

The concept of father involvement is regarded as a multidimensional construct that includes affective, cognitive and ethical components, inclusive of indirect forms of involvement (Castillo, Welch & Sarver, 2010; Hawkins et al., 2002; Kelly, 2007). Father involvement specifically refers to the quality of the father-child relationship and is conceptualised to include positive involvement in the child's activities (e.g. homework and school), the strength of the emotional tie between parent and child (e.g. feelings of closeness and positive relationships), authoritative parenting (e.g. effective discipline and parental guidance) and positive affective relationships (Kruk, 2010). The most influential definition of the concept remains the one offered by Lamb, Pleck and Levine (1986), who propose three components: interaction, availability and responsibility. Interaction refers to the father's direct contact with his child through care giving and shared activities. Availability is a related concept concerning the father's potential availability for interaction, by being present or accessible to the child, whether or not direct interaction is occurring. Responsibility refers to the role the father takes in ensuring that the child is taken care of and arranging for resources to be available to the child.

The limitations of this definition have been the focus of much debate and various alternatives have been proposed (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Pleck (2007:197) went as far as describing the search for a definition of father involvement as the "father involvement wars of the 1990s". Current research on father involvement is increasingly focusing on a complex set of variables to determine father involvement by including aspects such as feelings of closeness, shared activities, continued communication between fathers and children, and the more authoritative and guidance aspects of fathering (Dunn, 2004; Parke, 2000; Pleck, 2007; Smyth, 2005). Irrespective of their differences, scholars now increasingly agree that father involvement influences child outcomes in multiple pathways (Castillo et al., 2010). Hence, the authoritative original definition of Lamb et al. (1986) of father involvement that incorporates the three components of interaction, availability, and responsibility still remains the benchmark when embarking on research on father contact and involvement.

METHOD

Purpose and aim of research

This study had two primary research aims. The first aim was to conduct an examination of the amount of direct and indirect contact between adolescents and their non-resident fathers. Contact is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for non-resident fathers to contribute to their children's lives. Frequent contact also appears necessary for non -resident fathers to maintain high-quality relationships with their children and to engage in responsive parenting (King & Sobolewski, 2006). As such, it is important to include information on contact in studies of involvement of non-resident fathers. Second, this study also focused on four distinctive categories of father involvement, i.e. economic contributions, shared activities, communication and feelings of emotional closeness. The exploration of father contact in this study was distinctive because, in addition to determining the actual amount of direct and indirect contact, the quality of contact and father involvement was also investigated. Furthermore, possible gender differences in non-residential fathers' investment of time and resources were also scrutinised - an issue with conflicting results in current research (Stamps Mitchell, Booth & King, 2009).

It was deemed necessary to obtain information from the adolescents themselves, because very little research on divorce is based on the views of children themselves (Kaltenborn, 2004) and a considerable body of research is now arguing for children's participation in research (Campbell, 2008; Sinclair, 2004; Stafford, Latbourn, Hill & Walker, 2003). Furthermore, international research demonstrates that information obtained on parent-child relationships after divorce varies by source. For example, custodial mothers may underestimate fathers' contact and contributions to the well-being of their children (Cheadle et al., 2010), while fathers often tend to overestimate their involvement (Sarkadi, Kristiansson, Oberklaid & Bremberg, 2008). Thus adolescents should be in a better position than mothers and fathers to report on their experiences of their fathers' involvement in their lives.

Data gathering

The data used to answer the question came from participants at five secondary schools within the area of the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality. Written permission was obtained from the principals of all the schools prior to the commencement of the research. The children were presented with consent forms to provide to their parents to obtain permission to take part in the study. The schools were selected randomly to provide a representative sample of all the population groups, i.e. white, coloured, black, Indian or Asian. One of the schools represented children from an above-average socioeconomic demographic population (private Jewish schooling), while the remaining four schools represented children from middle to lower socio-economic demographic areas. The combined total of the schools was almost 1 800. The percentages of responses from the five different schools were respectively 20.5% (middle/lower socio-economic innercity school), 28.7% (middle socio-economic suburban school), 17.3% (upper socioeconomic suburban school) 19.3% (private school) and 14.2% (middle/lower class inner-city school).

Participants

The participants of this study were school-attending adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19 years (N=3523). The median age of the participants was 16 years. The median age of the group instead of the mean age is reported, because the ages of the respondents did not follow a normal distribution and 24 of the respondents did not indicate their ages. The participants included male (N=164) and female (N=183) adolescents with English as their language of scholastic instruction. The adolescents who indicated that their parents were divorced constituted 86 participants (24.4%) of the total sample. Forty-three percent (N=37) of the adolescents from divorced families were boys, and 57% (N=49) were girls. Thirty-three (89,2%) of the boys from divorced families were from the white population group, two (5.4%) from the black population group and two (5.4%) from the coloured population group. Of the 49 girls from the divorced group, four (8.1%) were black, 39 (80%) were white and five (10,2%) were coloured. There were no Indian or Asian participants for either gender group, and one girl (2.0%) did not indicate her race. Twenty-eight (76%) of the boys from divorced families and 29 (60%) of the girls from divorced families indicated that their parents had been divorced for a period of four years and longer.

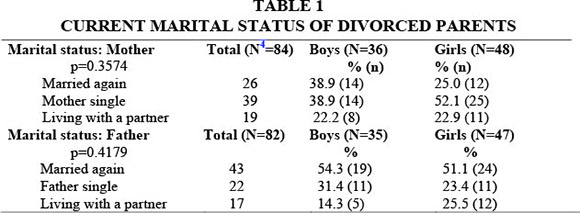

Of the 86 participants from the divorced group, 61 (70.9%) indicated that they were in the primary residential care of their mothers, 19 (22.1%) indicated that they primarily resided with their fathers, and four (4.7%) participants indicated that they lived with their extended families. Of the two remaining participants, one (1.2%) indicated a living arrangement with both mother and father, and one (1.2%) did not indicate the primary residence. The 61 participants who indicated that they resided primarily with their mothers constituted 26 (43%) boys and 35 (57%) girls. Table 1 gives an overview of the current marital status of the parents of the adolescents from divorced families by gender for the total number of participants from divorced families (N=86).

The results presented in Table 1 indicate that the majority of the male and female participants' fathers married again. Fewer male and female participants reported that their mothers married again, with 14 (38.8%) of the boys and 12 (25.0%) of the girls reporting that their mothers married again. As mentioned before, mothers marrying again or repartnering often poses potential difficulties in continued contact and involvement between fathers and their children after divorce (Smyth, 2005), because after forming new unions, some mothers may view contact with non-resident fathers as less necessary and hence they may no longer encourage or facilitate such contact (Cheadle et al., 2010; Hofferth, Forry & Peters, 2010). Non-resident fathers may also feel either that their role has been usurped by stepfathers or that their involvement is less necessary, given a new paternal role model in the household. Similarly, Dyer et al. (2011) indicate that when fathers marry again, it may have potentially negative consequences for contact and may even sever father-child relationships, since nonresident children often have to compete with new partners and/or new siblings. When fathers marry again, particularly when a child is born within the new union, paternal commitment to the children of a former marriage may diminish, seemingly because of the inability to maintain or deal with multiple commitments, conflicting loyalties and time demands (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Non-resident children may also choose to have less contact with their fathers when they marry again, possibly because of feelings of loyalty towards a displaced or emotionally fragile custodial parent (De Graaf & Fokkema, 2007). The findings in Table 1 seem to support international trends that indicate that three quarters of men eventually marry again, with 70% forming new unions (either by marrying again or cohabitation) within five years of divorce (Manning, Stewart & Smock, 2003).

Measuring instrument

The research participants were requested to complete a self-compiled questionnaire based on the research of Cheadle et al. (2010) on non-resident father contact and involvement. The first goal of the investigation was largely exploratory, i.e. to determine the number, nature and frequency of contacts between adolescents and their non-resident fathers. The second goal of the investigation was to describe the characteristics of the involvement of non-resident fathers to provide a profile of aspects relating to father involvement as identified by Lamb and his colleagues (1986). Information was obtained on the following aspects.

Biographical information: The adolescents recorded their age, gender, position in the family and ethnic group on a self-compiled biographical questionnaire. They also reported whether their parents were married, divorced or separated. If they indicated that their parents were divorced, they were asked to state how long their parents had been divorced (from a period of one year to four years and more) and whether their respective parents married again, and whether they were living with a partner or single.

Contact: The construct of (direct/indirect) contact was measured by asking how often the respondents had had direct contact with their fathers over the past month according to a set of contact schedules ranging from very frequent to infrequent and never. Adolescents also reported how often they had indirect contact with their non-resident fathers via telephone, SMS, e-mail or Facebook.

Father involvement: To enable the researcher to measure father involvement, the participants had to report on the four different categories of father involvement, i.e. financial contributions, activities, communication and emotional closeness. Financial contributions of fathers were measured, ranging from the payment of maintenance and school fees to pocket money and gifts to friends and family. Participants also had to report whether they had engaged in various leisure activities with their non-resident fathers in the previous month. This included shopping, attending a church service, attending a cultural event, playing a sport, seeing a movie, or going to a restaurant. Communication with their non-resident fathers was measured by asking whether they had engaged with their fathers in a variety of subjects ranging from their grades, school-related topics, social activities, personal problems, friends or their mother/siblings in the past month. Feelings of closeness were measured by a rating scale from 1, "not very close", to 5, "extremely close".

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed statistically using SAS Version 9.2. Descriptive statistics, specifically frequencies and percentages, were utilised for the categorical data. To compare the frequencies for the two adolescent gender groups, p-values (analytical statistics) were calculated to indicate significant gender differences. The Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to calculate the appropriate p-values. A significance level of 0.05 was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the study will be discussed next.

- Frequency of contact

The findings for the frequency of direct contact between adolescents (N=65) and their non-resident fathers are shown in Table 2. Overall, no significant gender differences were observed in the frequency of direct (face-to-face) contact.

*The percentages for boys and girls add up to more than 100% because more than one response was allowed.

The results for direct contact as indicated in Table 2 suggest that the majority of the participants primarily residing with their mothers reported regular contact with their non-resident fathers, ranging from daily contact to bi-weekly, weekly, once a week and every weekend, every second weekend and every holiday with no significant differences in the reported contact between boys and girls and their non-resident fathers. Girls reported higher levels of direct contact with their non-resident fathers on a daily basis when compared to boys, while boys reported higher levels of overnight visitation every second weekend than girls did. The reported results in this sample make it apparent that regular direct contact between non-resident fathers and their adolescent children is taking place. There were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls with regard to reported direct contact, and the present analysis provides very little support for the notion that fathers tend to have contact with their sons more frequently than with their daughters. However, because of the small size of the sample, these results should not be over-interpreted. The results seem to support the notion that direct overnight visitation seems to decrease during adolescence. For example, Cashmore, Parkinson and Tyler (2008) found that many adolescents do not stay overnight, with only 40% of 12- to 18-year-olds reporting that they had stayed overnight with their nonresident fathers during the past 12 months. Earlier studies by Mnookin and Maccoby (2002) indicate that many adolescents did not stay overnight because of competing social activities and possible changes in the father-child relationship during adolescence (Kelly, 2007; Youniss & Smollar, 1985). Stewart (2003) reported similar findings of 18% overnight stays for both male and female adolescents during school holidays and 23,5% for overnight visitation every second weekend. Jenkins and Lyons (2006) reported that 30% of Australian children did not stay overnight, and for older children, contact only during daytime might be the type of contact they preferred. In the UK research on a cohort of children in Bristol found that, where contact took place, for a third of children it was at least weekly and for 90% monthly (Dunn, 2004). Survey reports also show that 17% of fathers had some form of contact every day, with 8% seeing their children daily, 49% at least weekly, and 69% monthly. Between half and two thirds of children had overnight stays at least once a month. Similar results on contact were also found in a sample of well-educated fathers in California where the average amount of "dad time" was 30%, typically every second weekend plus a midweek overnight each week (Kelly, 2007). Overall, the results support international trends that older children seem to have fewer overnight visitations with their nonresident fathers, but continue to maintain contact in most cases.

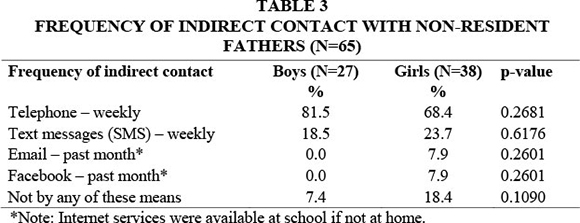

The results for indirect contact presented in Table 3 indicate that, of the 65 adolescents who reported on indirect contact with their non-resident fathers, most maintained contact by means of telephonic conversations, with more than 80% of the boys and almost 70% of the girls reporting this as their primary mode of indirect contact with their fathers. The majority of children reported far less frequent indirect contact by means of text messages. This may be because they did not have their own mobile telephones and/or access to mobile phones to initiate this type of contact, given the particular sociodemographic variables of the sample. It may also be because their fathers did not initiate this type of contact. With the increasing availability of access to mobile phones and the rapid changes in this type of communication, it may be postulated that, in all likelihood, this type of contact may increase when measured in future research in this area. Boys and girls alike reported very low levels of electronic contact with their fathers by means of email or Facebook. The girls reported higher levels of indirect electronic contact with their non-resident fathers than boys did. Overall, there were no significant differences in the reported indirect contact of boys and girls with their non-resident fathers.

Bailey (2003) indicates in her research on frequency of indirect contact that telephone calls were among the primary means employed by parents to remain in contact with their children. Even though the exact frequency of telephonic contact or whether the contact was initiated by the parent or the child was not measured in this study, the results support research findings of continued indirect paternal contact after divorce (Kaltenborn, 2004). Bailey (2003) further notes that email communication may become an increasingly popular means of contact between children and non-resident parents. With social networking media such as Facebook increasingly more available on mobile phones, there may be an increase in this type of contact as well in future, even though no literature is available currently to support this contention. It is encouraging to note that most of the children reported that, although their parents had been divorced for a period of four years or longer, they still had regular non-direct telephonic contact with their fathers. This supports findings in the literature that indirect contact with non-resident fathers does not necessarily decrease over time (Amato, Meyers & Emery, 2009; Castillo, 2010; Stamps Mitchell et al., 2009). The results of the current study further affirm Kelly's (2007) assertion that fathers in general have increased their levels of contact, and that between 35% and 60% of children now have at least weekly contact (direct or indirect) with their non-resident fathers.

- Financial contributions and activities

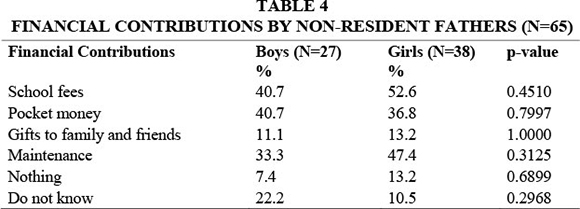

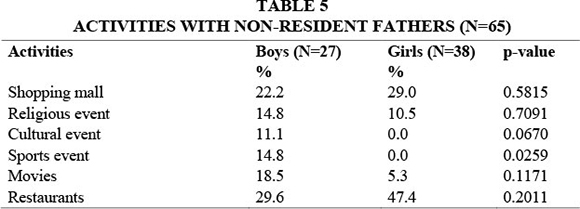

The financial contributions and activities of the non-resident fathers are presented in Tables 4 and 5 respectively.

The results for financial contributions by fathers presented in Table 4 indicate that, in this sample, both boys and girls reported the payment of maintenance by their fathers. Furthermore, 40% of the boys and more than 50% of the girls reported that their fathers not only contributed towards maintenance, but also towards school fees. Very few children indicated no financial contributions by their fathers, with only 7% of boys and 13.2% of girls indicating this aspect, while 22.2% of the boys and 10.5% of the girls reported that they were not aware of the financial contributions of their fathers. There are no significant differences in the reported results of boys and girls. In-kind support (Kane, Nepomnyaschy, Garfinkel & Edin, 2011), i.e. indirect financial contributions in the form of gifts and pocket money, were also reported by both boys and girls, albeit to a lesser extent. The results from this sample indicate that fathers do contribute towards inkind support in the form of pocket money, with 40.7% of the boys and 36.8% of the girls reporting this type of support. Less support is indicated in terms of gifts to family and friends. The results suggest the transfer of financial capital (Castillo, 2010) to offspring not only in terms of paying court-ordered maintenance but also in terms of alleviating some of the economic disadvantages faced by single mothers and a commitment by fathers to the educational future of their children. The literature consistently shows a positive association between the payment of child support and contact (Seltzer, 2000; Stewart, 2003). The inability to establish a causal order between the payment of maintenance and contact is endemic to most research that examines contact and the payment of child support (Seltzer, 2000). A study by Carlson, McLanahan and Brooks-Gunn (2008) indicates a causal direction running from financial contributions to positive parental relationships and father involvement during adolescence in particular, with financial contributions of fathers playing a particularly important role to maintain a sense of closeness to a non-resident father (Nepomnyaschy, 2007). Similarly, Cheadle et al. (2010) indicated that fathers who have regular direct and indirect contact with their children may become acutely aware of their children's economic needs and, hence, increase their financial contributions to their children.

The results for participation in shared activity presented in Table 5 indicate that the quality of time fathers tend to spend with their children varies in content and quality. On average, both boys and girls indicated the most frequent leisure activities were going to malls and eating at restaurants. Fathers engaged their adolescent boys more in activities such as playing sport and going to movies. Similar findings by King and Sobolewski (2006) suggest that fathers may engage their adolescent daughters more in terms of activities such as cooking, reading or art and less in terms of activities such as sport. Interestingly, the majority of the children indicated low levels of religious involvement by fathers as well as low levels of involvement in cultural activities of adolescents. The results in the current study indicate that fathers spend relatively little time in engaging their children in aspects other than shopping and restaurants, i.e. leisure activities. However, as Jenkins and Lyons (2006) indicate, non-resident fatherhood may well be the family context in which leisure features most prominently, as it is often shaped by legislation and a range of other moderating variables such as contact. The results may thus be a reflection of the reported contact schedules in place, i.e. that fathers have relatively limited uninterrupted long periods to engage in aspects of parenting that are more authoritative, such as involvement in school activities, cultural events and the religious upbringing of their children.

Hawkins, Amato and King (2007:992) demonstrated that "fathers who engage in a balanced mix of social and instrumental activities demonstrate that their children are important to them". Furthermore, Stamps Mitchell et al. (2009) indicate that participation in activities with non-resident children is of the utmost importance, since fathers who engage with their children in leisure provide social capital (Castillo, 2010) for children through involvement in school, churches and athletic organisations.

- Communication and emotional closeness

The findings concerning communication and emotional closeness are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

The results in Table 6 suggest that boys typically engaged their fathers more in communication regarding social events and school-related issues, while girls mostly engaged their fathers regarding school-related topics and friends. The results obtained on the disclosure of personal problems after divorce mirror results by Stewart (2003), which indicated that only 18% of children engaged their fathers in personal problems after divorce, while 41% engaged their fathers about schoolwork or grades, and 33% about other topics. More than 80% of the children who reported monthly contact in Stewart's (2003) study reported talking to their fathers about at least one of the topics listed above, suggesting that these items represent the kinds of things children and fathers discuss together. Thus, the results in this study appear consistent with previous research results that suggest that adolescent children, especially girls, are more comfortable with discussing nonemotional and school-related activities with their fathers than with discussing personal issues (Smyth, Caruana, & Ferro, 2004). The results may also indicate a tendency of adolescents to share more of their personal problems with their friends than with their parents, regardless of the marital status of their parents (Videon, 2005).

Table 7 compares boys' and girls' reports on their feelings of emotional closeness to their fathers. On average boys and girls reported similar levels of emotional closeness to their fathers, with almost 70% of the boys and 65% of the girls reporting emotional closeness varying from close to extremely close. This is an encouraging finding. Scott, Booth, King and Johnson (2007) state that the age of children may be a particularly important variable in determining levels of closeness, with older adolescents often reporting higher levels of closeness towards their non-resident parents. This may be related to their ability to differentiate between the mother-child and father-child bond, higher levels of individuation and separation from maternal figures, and the increasing development of autonomy.

According to Thomas, Krampe and Newton (2008), feelings of closeness to fathers, regardless of residence, often predict better outcomes for children. Emotionally close relationships between non-resident fathers and their children are particularly important, as fathers who have close relationships with their children can be more effective in monitoring, teaching and communicating with their children (King, Harris & Heard 2004). Furthermore, emotional closeness is likely to facilitate the transfer of fathers' financial resources to their children (Nord & Zill, 1996). Maintaining emotional closeness to nonresident fathers poses many obstacles for children with factors such as conflict between parents, lack of economic resources and visitation hindering these relationships. Despite this, children who reported being close to their fathers reported greater happiness and satisfaction with life, had lower levels of psychological distress and even reported higher levels of commitment to their future career choices (Mason, 2011).

CONCLUSIONS

Following the threefold conceptualisation of father involvement in terms of interaction, availability and responsibility, as suggested by Lamb et al. (1986), the results of this study indicate that non-resident fathers remain in contact and involved with their nonresident adolescents in a number of aspects considered critical for adolescent wellbeing and healthy developmental outcomes. In terms of the results obtained for direct contact, it is evident that most non-resident fathers are available to their adolescent children by means of direct interaction through various contact schedules and indirectly through telephone calls. Even though this study did not find many differences in contact of fathers with their sons and daughters respectively, it showed consistent contact between fathers and their children over an extended period, regardless of whether the fathers married again. The most encouraging finding in this study is that, even though fathers may be absent from their children's households, fathers are not necessarily absent from their lives and continue to play an important part in terms of the engagement and accessibility dynamics of father involvement.

This study did not focus on children's satisfaction with the rates of contact, but there is ample evidence that most children want more contact with their non-resident parents and that an increase in contact with a non-resident parent often results in better relationships with both parents (Cashmore et al., 2008), an aspect that is of particular importance during adolescence. Overall, the interpretation of the results obtained from the questionnaire suggests that, in this cohort of adolescents, non-resident fathers remained in contact with the lives of their male and female adolescents over long periods, which is consistent with Dunn's (2004) findings that fathers are increasingly more engaged in relationships with their children after divorce. However, even though contact is taking place, it is evident from the results of this study that non-resident fathers' involvement in the daily lives of their children, including routine and special moments, may be limited to predominantly leisure activities by virtue of the particular type of contact schedule in place. This leaves concerns regarding the more authoritative and guidance-providing aspects of parenting, such as involvement in school, cultural and religious activities, since the results indicate limited involvement in this regard. It may also suggest that, even though fathers contribute financially towards maintenance and school fees, they express less direct involvement in aspects such as the supervision of homework and engage less in communication regarding aspects such as discipline and instilling a value system. This may be particularly problematic during adolescence and further sever the relationship between parents after divorce. Mothers may feel increasingly overburdened, not only in terms of making financial contributions towards their adolescent children, but also by providing most of the authoritative aspects of parenting for their children. In essence, this only promotes the derogatory perception that non-resident fathers only contribute towards leisure activities with their children while being absent otherwise.

International studies on non-resident father involvement during adolescence reflect similar results. Phares, Fields and Kamboukos (2009) reported in their study that mothers had the bulk of responsibility in terms of authoritative parenting and responsibility for adolescents' school work. Their results also indicate that, for discipline, daily care and recreational activities, mothers have significantly more responsibility than fathers have. Numerous studies have investigated whether the amount of contact and the quality of relationships with fathers after divorce are predictive of their children's adjustment and wellbeing. Although mixed results have been found, the majority of studies indicate that the father-child relationship after divorce, in particular with regard to authoritative parenting and emotional closeness, is associated with more positive outcomes for children (Dunn, 2004; Flouri, 2006). During adolescence, in particular, these qualities are linked to higher social competence, lower externalising behaviour and better long-term wellbeing (Hofferth et al., 2010). Therefore, the importance of fathers should not be underestimated.

In conclusion, there are three broad limitations in this research. First, the study was limited to a few variables in self-administered questionnaires for children. Since adolescents reported on both the contact and the involvement of their non-resident fathers, the findings may reflect reporting bias (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). The methods for assessing paternal involvement may also be problematic. Other studies in this field of research have used time-sampling (such as a pager that alerts the participant to report contact) or time diaries to assess parent-child contact and involvement as it occurs (Phares et al., 2009). Although the use of questionnaires is well established in assessing paternal involvement and the measures used showed adequate reliability, a more direct assessment of time involvement and parental responsibility may have improved the information collected about contact and involvement. In addition, comparing adolescents', mothers' and fathers' perspectives about contact and involvement may also have been worthwhile.

Second, the study did not involve control measures for mother involvement, and the type of questions did not give adolescents the opportunity to comment on their relationships with their mothers or the prescribed schedules of contact with their non-resident fathers and whether their mothers were rigidly adhering to contact schedules ordered by court. This is important, as positive mother-child relations are deemed important in fostering contact and continued involvement between non-resident fathers and their children (Flouri, 2007). As such, the specific dimensions of the interactions of parents regarding their children were not considered, and aspects such as high general conflict in relationships between parents after divorce and the possible effect of the conflict on father-child contact were not taken into account. The quality of the mother-child relationship has been found to relate to the quality of the father-child relationship (King & Sobolewski, 2006). Future research should also focus on determining mothers' perspectives on the quality of the relationship between adolescents and their non-resident fathers. Mothers should also comment on the type of contact schedules and whether they initiate the contact between children and their fathers. A further important aspect regarding mother involvement would have been to assess mothers' perspectives on the financial contributions of fathers and whether this had an effect on contact with the father. Mothers' perspectives on the leisure aspect and communication between children and their non-resident fathers would also have been a valuable contribution in this study.

Third, given the small size of the sample, the degree of variance in the children's accounts of contact with and involvement of non-resident fathers was generally modest, although the findings are in line with a number of international studies in the same area of research (Hofferth, 2006). However, it may be valuable to determine whether the same trends would have been evident in lower socio-economic groups, where fathers may show less dedication in maintaining regular contact and involvement. Thus, given the fact that most of the adolescents reported regular direct and indirect contact and high levels of involvement, the findings of this study cannot be generalised to families in which the fathers have limited and/or no contact with their adolescent children. Despite these limitations, it is hoped that this study will stimulate interest in the study of nonresident fathering to ensure better outcomes for children affected by divorce.

REFERENCES

AMATO, P.R., BOOTH, A., JOHNSON, D.R. & ROGERS, S.J. 2006. Alone together: how marriage in America is changing. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

AMATO, P.R. & GILBRETH, J.G. 1999. Non-resident fathers and children's wellbeing: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61:557-574. [ Links ]

AMATO, P.R., MEYERS, C.E. & EMERY, R.E. 2009. Changes in non-resident father-child contact from 1976 to 2002. Family Relations, 58(2):41-53. [ Links ]

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION. 2012. Divorce and remarriage. American Psychologist, 88:761-770. [ Links ]

BAILEY, S.J. 2003. Challenges and strengths in non-residential parenting following divorce. Marriage and Family Review, 35(1):29-44. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL, A. 2008. The right to be heard: Australian children's views about their involvement in decision-making following parental separation. Child Care in Practice, 14(3):237-255. [ Links ]

CARLSON, M.K., MCLANAHAN, S.S. & BROOKS-GUNN, J. 2008. Co-parenting and non-resident fathers' involvement with young children after a non-marital birth. Demography, 45:461-488. [ Links ]

CASHMORE, J., PARKINSON, P. & TAYLOR, A. 2008. Overnight Stays and Children's Relationships with Resident and Nonresident Parents after Divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6):707-733. [ Links ]

CASTILLO, J.T. 2010. The relationship between non-resident fathers' social networks and social capital and the establishment of paternity. Child Adolescence Social Work Journal, 27:193-211. [ Links ]

CASTILLO, J.T., WELCH, G. & SARVER, C. 2010. Fathering: The relationship between fathers' residence, fathers' socio-demographic characteristics, and father involvement. Journal of Maternal Child Health, 15:1342-1349. [ Links ]

CHEADLE, J.E., AMATO, P.R. & KING, V. 2010. Patterns of nonresident father contact. Demography, 47(1):205-225. [ Links ]

CHILDREN'S ACT 38 OF 2005. 2006. Government Gazette, Vol. 492, No. 28944. [ Links ]

CLARKE-STEWARD, A. & BRENTANO, C. 2006. Divorce: causes and consequences. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

DE GRAAF, P.M. & FOKKEMA, T. 2007. Contacts between divorced and nondivorced parents and their adult children in the Netherlands: an investment perspective. European Sociological Review, 23(2):263-277. [ Links ]

DE LOS REYES, A. & KAZDIN, A.E. 2005. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for future study. Psychological Bulletin, 13(4):483-509. [ Links ]

DUNN, J. 2004. Annotation: Children's relationships with their non-resident fathers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(4):659-671. [ Links ]

DUNN, J., CHENG, H., O'CONNOR, T.G. & BRIDGES, L. 2004. Children's perspectives on their relationships with their non-resident fathers: influences, outcomes and implications. Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(3):553-556. [ Links ]

DYER, K., JINI, L.R., MUPEDZISWA, R. & DAY, R. 2011. Father involvement in Botswana: How adolescents perceive father presence and support. The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(4):426-431. [ Links ]

EMERY, RE. 1994. Renegotiating family relationships. Divorce, child custody, and mediation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

FABRICIUS, W.V. & BRAVER, S.L. 2003. Non-child support expenditures on children by non-residential divorced fathers: Results of a study. Family Court Review, 41:350362. [ Links ]

FINLEY, G.E. 2006. The myth of the good divorce. Contemporary Psychology, 51:3243. [ Links ]

FLOURI, E. 2006. Non-resident fathers' relationships with their secondary school age children: Determinants and children's mental health outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 29:525-538. [ Links ]

FLOURI, E. 2007. Fathering and adolescents' psychological adjustment: The role of fathers' involvement, residence and biology status. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(2):152-161. [ Links ]

GONCY, E.A. & VAN DULMEN, M.H.M. 2010. Fathers do make a difference: parental involvement and adolescent alcohol use. Fathering, 8(1):93-108. [ Links ]

HAWKINS, A.J., BRADFORD, K.P., PALKOVITZ, R., CHRISTIANSEN, S.L., DAY, R.D. & CALL, V.R.A. 2002. The inventory of father involvement: a pilot study of a new measure of father involvement. The Journal of Men's Studies, 10(2):183-196. [ Links ]

HAWKINS, D.H., AMATO, P.R. & KING, V. 2007. Non-resident father involvement and adolescent well-being: Father effects of child effects? American Sociological Review, 72:990-1010. [ Links ]

HAWTHORNE, B. & LENNINGS, C.J. 2008. The marginalization of non-resident fathers: Their postdivorce roles. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 49(3):191-208. [ Links ]

HETHERINGTON, E.M. & KELLY, J. 2002. For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York, NY: Norton. [ Links ]

HOFFERTH, S.L. 2006. Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection. Demography, 43:53-77. [ Links ]

HOFFERTH, S.L., FORRY, N.D. & PETERS, H.E. 2010. Child support, father-child contact and preteens involvement with nonresidential fathers: Racial/ethnic difference. Journal of Family Economic Issues, 31: 14-32. [ Links ]

HOLMES, E.K. & HUSTON, A.C. 2010. Understanding positive father-child interaction: Children's, father's and mother's contributions. Fathering, 8(2):203-225. [ Links ]

JENKINS, J. 2006. Non-resident fatherhood: Juggling time. Paper presented at the Australian Political Studies Association Conference, University of Newcastle. 21 September 2006. [ Links ]

JENKINS, J. & LYONS, K. 2006. Non-resident fathers' leisure with their children. Leisure Studies, 25(2):219-232. [ Links ]

JUBY, H., BILLETTE, B., LAPLANCE, B. & LE BOURDAIS, C. 2007. Non-resident fathers and children: Parents' new unions and frequency of contact. Journal of Family Issues, 28:1220-1245. [ Links ]

KALTENBORN, K. 2004. Parent-child contact after divorce: The need to consider the child's perspective. Marriage and Family Review, 36(1-2):67-90. [ Links ]

KANE, J.B., NEPOMNYASCHY, L., GARFINKEL, I. & EDIN, K. 2011. In-kind support from non-resident fathers: A population level analysis. Family Process, 57:3364. [ Links ]

KELLY, J.B. 2007. Children's living arrangement following separation and divorce: insights from empirical and clinical research. Family Process, 46(1):35-64. [ Links ]

KING, V., HARRIS, K.M. & HEARD, H.E. 2004. Racial and ethnic diversity in nonresident father involvement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66:1-21. [ Links ]

KING, V. & SOBOLEWSKI, J.M. 2006. Nonresident fathers' contributions to adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68:537-557. [ Links ]

KRUK, E. 2010. Parental and social institutional responsibilities to children's needs in the divorce transition: Fathers' perspectives. The Journal of Men's Studies, 18(2):159-178. [ Links ]

LAMB, M.E., PLECK, J. & LEVINE, J. 1986. The role of the father in child development: the effects of increased paternal involvement. In: LAHEY, B.B. & KAZDIN A.D. (eds). Advances in clinical child psychology. New York, NY: Plenum, 229-266. [ Links ]

LOUW, A. 2010. The constitutionality of a biological father's recognition as a parent. Psychological Electronic Resources, 13(3):156-206. [ Links ]

MANNING, W., STEWART, S.D. & SMOCK, P.J. 2003. The complexity of fathers' parenting responsibilities and involvement with non-resident children. Journal of Family Issues, 24(5):645-667. [ Links ]

MASON, H.M. 2011. Nonresident fathers parenting and child and adolescent outcomes. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University. (Doctoral Dissertation) [ Links ]

MNOOKIN, R.H. & MACCOBY, E.E. 2002. Facing the dilemmas of child custody. Virginia Journal of Social Policy and the Law, 10:54-88. [ Links ]

NEPOMNYASCHY, L. 2007. Child support and father-child contact: Testing reciprocal pathways. Demography, 44(1):93-112. [ Links ]

NORD, C. & ZILL, N. 1996. Non-custodial parents' participation in their children's lives: Evidence from the survey of income and program participation. Westat: Rockville, MD. [ Links ]

PALKOVITZ, R. & PALM, G. 2009. Transitions within fathering. Fathering, 7(1):3-22. [ Links ]

PARKE, R.D. 2000. Father involvement: a developmental psychological perspective. Marriage and Family Review, 29(2):43-58. [ Links ]

PHARES, V., FIELDS, S. & KAMBOUKOS, D. 2009. Fathers' and mothers' involvement with their adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 181-189. [ Links ]

PLECK, J.H. 2007. Why could father involvement benefit children? Theoretical perspectives. Applied Development Science, 11(4):196-202. [ Links ]

PLECK, J.H. & MASCIADRELLI, B.P. 2004. Paternal involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, sources, and consequences. In: LAMB, M.E. (ed). The role of the father in child development (4th ed). New York, NY: Wiley, 222-271. [ Links ]

SARKADI, A., KRISTIANSSON, R., OBERKLAID, F. & BREMBERG, S. 2008. Fathers' involvement and children's developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Peadiatrica, 97:153-158. [ Links ]

SCOTT, M.E., BOOTH, A., KING, V. & JOHNSON, D.R. 2007. Post-divorce father-adolescent closeness. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69:1194-1209. [ Links ]

SELTZER, J.A. 2000. Relationships between fathers and children who live apart: the father's role after separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53:79-101. [ Links ]

SINCLAIR, R. 2004. Participation in practice: Making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Children and Society, 18:106-118. [ Links ]

SMYTH, B. 2005. Time to rethink time? The experience of time with children after divorce. Family Matters, 71:4-10. [ Links ]

SMYTH, B., CARUANA, C. & FERRO, A. 2004. Father-child contact after separation: Profiling five different patterns of care. Family Matters, 67:20-27. [ Links ]

SOBOLEWSKI, J.M. & KING, V. 2005. The importance of the co-parental relationship for non-resident fathers' ties to children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67:11961212. [ Links ]

STAFFORD, A., LATBOURN, A., HILL, M. & WALKER, M. 2003. Having a say: Children and young people talk about consultation. Children and Society, 17(5):361-373. [ Links ]

STAMPS MITCHELL, K., BOOTH, A. & KING, V. 2009. Adolescents with nonresident fathers: Are daughters more disadvantaged than sons? Journal of Marriage and Family, 71:650-662. [ Links ]

STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA. 2010. Marriages and divorces: statistical release. Pretoria. [ Links ]

STEWART, S.D. 2003. Nonresident parenting and adolescent adjustment: the quality of the nonresident father-child interaction. Journal of Family Issues, 24(2):217-244. [ Links ]

THOMAS, P.A., KRAMPE, E.M. & NEWTON, R.R. 2008. Father presence, family structure, and feelings of closeness to the father among adult African American children. Journal of Black Studies, 38(4):529-546. [ Links ]

VIDEON, T.M. 2005. Parent-child relations and children's psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 26(1):55-78. [ Links ]

WILSON, G.B. 2006. The non-resident parental role for separated fathers: A review. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 20:286-293. [ Links ]

YOUNISS, J. & SMOLLAR, J. 1985. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers and friends. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

1 As indicated by the APA (2010), despite changes in terminology in the common law concepts of custody and access to "care" and "contact" to better reflect the rights of children, the substantial majority of legal authorities and scientific treatises still refer to the term "custody" and "access" when addressing the resolution of decision making in care and contact disputes. In this paper the concepts "custody" and "access" are retained to provide continuity with regard to past research and international literature. Consequently, both the old and new terms are used for the sake of clarity with "custody" also referring to "care" and "access" to "contact" and vice versa.

2 In this paper the term "non-resident" father refers to fathers who do not reside with their biological children by virtue of divorce.

3 N does not always equal 352 because the participants did not always provide the information required.

4 N does not always equal 86 as responses were only included in the sample when the data collected were for aspects that could be assessed. For example, some of the adolescents did not respond to all of the items.

5 N does not always equal 65 because not all the adolescents with non-resident fathers answered all the questions.