Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.1 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-16

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-16

The life experiences of adolescent sexual offenders: Factors that contribute to offending behaviours

Linda NaidooI; Vishanthie SewpaulII

IDepartment of Social Work, School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD; Department of Social Work, School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

There may be little opportunity of changing an offender's behaviour unless there is understanding of the factors that contribute to it. The inability to understand behaviour from the offender's perspective means that there is a risk of adopting inappropriate programmes, which will do little to address offending in comprehensive and appropriate ways. The reasons that offenders give for offending may seem totally irrational or unacceptable, but it is the reality of their world. Only by seeing it through their eyes can practitioners understand what motivates their behaviour, help them to change (Briggs, 1995:vii) and develop strategies for secondary and primary prevention of sexual abuse (Worling & Curwen, 2000). Between 30-50% of all child molestations are perpetrated by adolescent males (Oates, 2007). Because of the under-reporting of sexual abuse of children by adolescents, it is difficult to obtain accurate statistics in South Africa.

According to Dennison and Leclerc (2011), developmental and life course perspectives have been particularly informative in identifying risk and protective factors for offending. These factors include the potential importance of individual developmental factors and the significance of family, peer, school, neighbourhood environments as well as broader structural factors linked to poverty, social exclusion, discrimination and oppression. It is generally assumed that sexual offenders, including juvenile sexual offenders, will commit further sexual offences in the absence of appropriate intervention (Vizard, Hickey, French & McCrory, 2007). There is a need to understand the aetiology of sexual offending in order to find appropriate ways to prevent it. Assumptions about sexual offending influence sentencing and correctional practices, as well as our approaches to psychosocial intervention.

Of particular relevance to this article is the Child Justice Act, 75 of 2008 (Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, 2008), which establishes a criminal justice system for children who are in conflict with the law, in accordance with the values underpinning the South African Constitution and our international obligations. The Act expands and entrenches the principles of restorative justice, with diversion and alternative sentencing programmes for children who are in conflict with the law, while ensuring acknowledgement of their responsibility and accountability for crimes committed. The Act also recognises the realities of crime in the country and the need to be proactive in crime prevention. It places increased emphasis on the effective rehabilitation and reintegration of children to minimise the potential for re-offending, and it seeks to balance the interests of children and those of society with due regard for the rights of victims. The data presented in this paper are based on research with 25 adolescent sexual offenders, with the developmental objective of making recommendations aligned with the Child Justice Act.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research, which was primarily qualitative in nature, was informed by family systems theory and the ecosystems model. Within the qualitative paradigm the collective case study design was used, with 25 participants. The focus of the study was on the participants' childhood experiences, circumstances and relationships within the family, and the family's vulnerability to external structural factors. Of the 40 male adolescent sexual offenders who were receiving services at Childline, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), 25 were included in the study adopting the theoretical sampling strategy, which involves the purposeful selection of a sample in the initial stages of the study, building up to data saturation (Coyne, 1997). The study drew on information that was quantified, retrieved from the participants' case files and from in-depth interviews, and it reflected the voices of adolescent sex offenders that were qualitatively analysed. Data were obtained over a period of two years. The secondary data included reports produced during the initial assessment of the participants, as well as reports on file, such as victim statements. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, were assured that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without any negative consequences. They were assured of complete anonymity in the reporting of the data, and that the information gathered would be used for research purposes only.

The main aim of the research was to understand the impact of the interacting context of the family and its environment on the adolescent sex offender, and how these factors may influence offending behaviour. There are various mezzo and macro forces which contribute to the development of offending behaviour, but the focus of this research was on a micro level - that is, the individual and the family.

The key research questions were:

- What are the life experiences of the adolescent sex offender?

- What is the quality of the adolescents' interpersonal relationships with family and peers?

- What information did the adolescent obtain about sex and how did this shape his perceptions of sex and influence his offending behaviour?

- What are the possible predisposing and precipitating factors that culminate in the offending behaviour?

RESULTS

This section introduces the participants by age at which the offending behaviours commenced, their choice of victims and the types of offending behaviour that they engaged in.

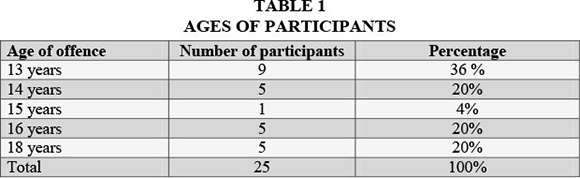

Thirty-six per cent of offenders committed sexual offences at the age of 13 years and younger. As reflected in the table below, the most common sexual offences were penetrative acts of sodomy and rape, with 31 victims being exposed to these acts.

The above table reflects the ages and sex of the victims; relationship of the victims to the offender; and the type of sexual abuse committed. There were approximately 55 victims to 25 adolescents offenders, that is 2.2 victims per offender. The victims' ages ranged from three years to 40 years, with all except one being children. The single age category with the highest number of victims was 13 years, depicting 12 victims. Twenty-four of the victims were eight years or below, displaying this as the most vulnerable group. This was consistent with statistics from Childline, as 50% of all sexual abuse cases reported are of children below the age of 8 years. Forty of the victims were female; 15 victims were male.

The data reflected that a large proportion (15) of the offences occurred in CYCC, although five of the participants were from institutions, meaning that the average was three victims per participant. This was closely followed by sisters or step-sisters (10), neighbours (10) cousins (8) and friends (7). The data supported the idea that sexual offending is an opportunistic crime, thriving on easy access to victims and the hope that the abuse would remain a secret. The data challenges the myth of "stranger danger". The greatest threats to bodily integrity and security, and their horrendous psychosocial ramifications, lie with people who are close and are known to the victims (Lanning, 2001). Ninety-two per cent of the victims were known to the offenders. Eleven (44%) of the offenders were brothers, which was consistent with data from Childline, where incest constitutes the largest number of sexual offences, with many of these not being reported to the police. The section that follows discusses the various factors that might have contributed to offending behaviours.

THE LIFE EXPERIENCES OF OFFENDERS

Multiple forms of abuse and repeated abuse were commonly perpetrated by this sample of adolescents. This may be due to inappropriate learning, failed interventions, opportunity, lack of discovery, and to circumstances within the family and the external environment. While there were a range of predisposing factors, viewing pornography and peer influence emerged as important precipitating factors. The majority of participants reported watching pornography, being stimulated by this and wanting to experiment on what they had seen. Twenty-two of the juveniles were exposed to pornography, and in most incidents the pornographic material constituted immediate precipitants for the sexual abuse, as reflected in the comments from the following participants.

"I watched a movie, which was for adults at my friend's house and saw men having sex with each other, so I thought it would not hurt that child (victim). I thought he would enjoy it, and he did, because he stayed quiet when I did it. I felt good. It was the first I did what my friends talk about and what I see in the pictures and movies ... Sex feels nice." (Bern)

"I watched bad things on television and I saw Hustler magazines that I got from my big brother. I had an 'explosive' feeling inside of me when I watched the pornographic movies." (Vikesh)

"From television and friends I learnt how to arouse females. I learnt about their genitals, why their nipples pop. From about 11 till 15 years I fantasised about Pamela Anderson and me 'sexing' on the beach ... Whilst watching one film, I saw inmates gang raping another inmate. At first I thought it was disgusting and terrible, but after a while I began fantasising about doing it to someone. That 's when I started to think about me hurting someone else." (Vicki)

"I watched a blue movie before I abused the girl." (Fred)

A common source of support for most of the adolescents was their friends, who unfortunately reinforced negative behaviour patterns. Citing Levant and Brooks (in Petersen, Bhana & McKay, 2005:1238) assert that "delinquent peer groups have long been identified as training grounds for 'hypermasculine' and 'hostile masculinity,' both associated with sexual and nonsexual coerciveness". Jewkes, Nduna, Jama Shai and Dunkle (2012) also highlighted the power of peer influence and of substance abuse in the case of rape in South Africa.

This study reflected the various forms of abuse that the adolescent offenders have themselves been exposed to: 68% were physically abused; 78% were sexually abused and all were exposed to emotional abuse. Many had been exposed to a combination of sexual, physical and emotional abuse. They experienced difficult family dynamics: 78% were exposed to domestic violence, while 68% had either one or both parents who abused substances. Many of them experienced relationship problems with their parents. Living in homes with poor role models, poor parenting, neglect and stressed single parents, and with fathers being absent either physically or emotionally was the norm.

The majority (88%) of the adolescents were exposed to pornographic material and inappropriate sexual messages from peers and family members. The knowledge and values about sex and related relationship issues among all the participants were distorted and limited. The data revealed that in some families sexual abuse existed across several generations. Patterns of behaviour in the extended family were similar to those of the family of origin, with alcoholism, sexual abuse, exposure to pornographic material, instability, inconsistent discipline, depression, and physical and emotional abuse.

All of the participants reflected poor self-concepts and low self-esteem, were unable to express their feelings and had difficulty showing empathy. The assessment was collaboratively made via assessment tools, for instance, the Pier Harris Self-esteem Scale, Hudson Scales and clinical interviews over a period of two years. They acted out with anger and aggression, were isolated and had difficulty maintaining relationships. Few had a best friend. Their relationships were characterised by negative peer influences, with many of them seeking support from gangs. According to Dennison and Leclerc (2011), social isolation and poor social skills are two of the risk factors common to both general adolescent criminality and adolescent sexual reoffending. Poor adolescent-parent relationships is a high risk factor for sexual recidivism. Drawing on the qualitative data, the remainder of the results are discussed under the following headings: family violence, substance abuse, poor parenting and inter-generational patterns of abuse.

Family violence

The adolescent offenders told compelling stories of difficulties within their families, including domestic violence, some of which are reflected below.

" When I was just older than 4 years I saw my father trying to kill my family. He locked us into the house and said, 'I will kill everyone starting with my eldest son '. My father hit my brother with a stick and he hit my mother and said, 'Watch your children die, I will kill you with a bush knife'." (Sipho)

Adolescents like Sipho were held captive in a passive role and were forced to witness the horror of violent acts. The more personal these acts are, the greater the potential for trauma and subsequent acting out behaviour.

"I can remember my father getting drunk and always hitting my mother and I could not do anything. My father eventually killed my mother - according to my cousin he killed her with an ironing board." (Sipho)

This was corroborated by collateral data. According to social workers, James's father had an aggressive nature and also assaulted the paternal grandparents, as a result of which the paternal grandmother was hospitalised and subsequently died. Similar to the reactions of children who have been physically abused, the reactions of children who chronically witness family violence may contribute to cognitive, emotional and/or behavioural disturbance. Children in violent homes learn that violence is an appropriate way of resolving conflict in intimate relationships, and that assaultive behaviour and threats are effective means of maintaining power and control over other people (Reckdenwald & Beauregard, 2013). They tend to rationalize the use of violence when confronted with stressful life situations, and believe that victims bring it upon themselves on account of their own weakness. Participants reported that arguments over sex were likely to be one of the reasons for the beating of women, which was often accompanied by verbal and sexual abuse. One of the participants, Fred, said:

"All my mother 's boyfriends are bad - they always drank alcohol a lot and hit her, one also sexually abused my stepsister, another drugged his daughter and sexually abused her in our house."

The above examples highlight the issues of inappropriate models in the home; physical and sexual aggression; and women's inability, especially in the face of economic dependence on men, to protect themselves and their children from alcohol, drug and child abuse. According to Borduin, Munschy, Wagner and Taylor (2011), there is a connection between low rates of parental monitoring, high rates of parent-child and interpersonal conflict and violence, high rates of substance abuse, low attachment, low rates of communication and warmth, and low academic performance and socially inept adolescents. As borne out in this and other studies by Vizard et al. (2007), these are predisposing factors to sexual offending. Substance abuse constituted a critical problem among the families of the adolescents.

Substance abuse

Alcohol abuse by the partner who inflicts physical abuse compounds the family's disorganisation, and the abuser and his victim usually minimise the violent behaviour and focus on the alcohol as the root cause of family problems. Continued alcohol abuse leads to serious emotional, economic and social consequences for the family, which creates a greater need for the victim to look after the abusive partner. In the meantime the children are left to continue coping with the violence in the context of deepening psychological, economic and social disadvantage. There is an enduring belief that alcohol and violence are intimate partners. This is an attractive view for the perpetrator of violence, for the alcohol provides an evasion of responsibility. Alcohol on its own does cause violence, because it tends to reduce inhibitions (O'Halloran & O'Reilly, 2002). The following case is typical of the interaction between alcohol and violence, with alcohol seen reducing culpability even in murder.

"I can remember my father getting drunk and always hitting my mother. I could not do anything. But I have forgiven my father for killing my mother, because he was drunk. I feel lonely and hurt in my heart. I missed my mother because we got on well and then I was put into a foster home. My foster father also just drank all the time and swore us and hit us." (James)

Alcoholism is a debilitating addiction. While alcohol reduces stress, it allows people to engage in deviant behaviours without feeling responsible for the consequences. Substance abuse contributed to other problems such as evasion of responsibilities, loss of employment and unwillingness to support the family financially, thus leading to impoverishment in most families, seen in this research.

Emotional, physical and sexual abuse have been correlated with alcohol misuse. The child of the alcohol-abusing parent is the scapegoat who gets the blame, the child who is ignored or assaulted. These roles develop to hide the scars of living in such a family. Children living with such parents internalise a sense of rejection and react with a pseudo-parental role reversal in which they care not only for their younger siblings but for their parents as well. Substance-abusing families tend to be characterised by low levels of cohesion, low frustration tolerance, unrealistic expectations of children, role reversal and poor parenting skills. These traits are linked to abusive family systems. Children of substance abusers have been shown to have lower self-esteem; to be lacking in affirmation and nurturance; and have higher levels of unmet dependency needs (Hunter, Figueredo, Malamuth & Becker, 2003). These are characteristics that may increase vulnerability to victimisation by others external to the family. Neglect of children may result in removals, which can aggravate the situation for the child, as seen in the case of James above.

Poor parenting

One of the participants in this study, Fred, was placed in a residential facility when he was 4 years old and subsequently developed problems in his relationships with his parents as well as stealing, academic problems and lack of emotional expression.

"I don't mind stealing or hurting my family, but I would not steal from my friends. Family comes last, they reject you, and they can do anything to ruin your life for you. My granny who cared for me used to chase me, swear me; my mother 's brother whipped me, even though I have grown up and working. " (Fred)

Fred experienced no attachment to his family; he felt hurt and betrayed by them. He showed little empathy for others and had learnt to survive without the assistance of family. The consequences of neglect are the failure to bond, manifesting in difficulty in forming intimate relationships (Winokur, Devers, Hand & Blankenship, 2009). Neglected individuals grow up feeling unwanted by the world and are often repulsed by touch and affection. The results of this study show that they become hardened and harbour deep feelings of rage and resentment towards their parents and the world, often disguising a much deeper pain about feeling unloved. Mothers were emotionally distanced and depressed.

In the study women facing stressful life circumstances struggled to cope with the demands of child rearing, as reflected in the story of Vicki.

"My mother has always experienced depression - and could not do everything for us. Because of my mother's depression, she does not perform her duties of cooking, cleaning, but sleeps a lot, she forgets things, and she is sometimes confused." (Vicki)

Most of the mothers came from unstable backgrounds and were in abusive relationships. Vicki's father, for instance, was authoritarian, physically and emotionally abusive, engaged in extramarital affairs and was not supportive of them. As a result the parenting of the children was largely neglected. Abused and abusive mothers tend to rely on their children to gratify their dependency needs, and project their own negative attributes and feelings of decreased self-worth onto their children. Families described as dysfunctional or unstable, and parents themselves, have often experienced chaotic or disturbed childhoods, leaving them with a legacy of inadequate parenting models, and poor behavioural and sexual boundaries. Parents of these children often have their own mental health problems, have suffered childhood abuse and demonstrate entrenched patterns of domestic violence, which is an independent predictor of later perpetration of sexual offences by male children. Poor parental sexual boundaries have been identified as a risk factor for sexually abusive behaviour by children and as an strong predictor of the early onset of sexually abusive behaviour (Vizard et al., 2007). Parents who abuse their children were themselves, as children, deprived and subject to parental violence. In relation to the cycle of violence, it appears that individuals learn how to treat others through the type of abuse inflicted on them. The experience of trauma early in life may manifest differently in individuals, with some research suggesting that certain forms of abuse may have an impact on crime in later adult life, such as sex offending (Reckdenwald & Beauregard, 2013 ).

The following case example of Nevi describes the dynamics of intergenerational neglect and abuse. Nevi's maternal grandmother was a single parent who could not care for her many children born out of wedlock from different relationships and they, including Nevi's mother, were subsequently removed to a children's institution.

"My mother appeared to have grown up in guilt and depression. She has a loser attitude in life; everything is so hard, like the cooking and cleaning. She has to take tablets to keep her moving in life. I cannot have a close relationship with her. She pushes me away and chases me when I want to go too close to her." (Nevi)

Depression may affect parenting by reducing the effort that parents put into interacting with their children, as in the case of Nevi and many other parents in this study. Clinically depressed mothers show sadness, speak less often to their young children, enforce obedience unilaterally or withdraw when faced with child resistance, and are more irritable and hostile with their families. Inconsistent and punitive discipline practices by parents can contribute to children's under-regulation of anger and aggression that can be destructive of property and personal relationships. Hence, the abusive behaviour and negative attitudes toward, or rejection of, the child may lead to attachment difficulties and consequently aggressive and antisocial behaviour at an early age (Smallbone, 2005). Dysfunctional parenting, manifesting in physical maltreatment, inappropriate maternal provision and dependence on children for emotional fulfilment, may contribute to the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment (Hagele, 2005).

The fathers of the adolescents in the study were mainly absent, as most mothers were unmarried, had minimal contact with their boyfriends, or were uncertain about the whereabouts or identities of the fathers of their children. One of the participants, Lager, reported: "I want my father to do things with me. I miss my father a lot, but he does not want me, he does not even come to visit me."

The adolescents in this study felt uncared for, sometimes unloved, mistrusted, worthless and unwanted. Thus they in turn interacted with minimum confidence in their relationships, were subject to peer influence, acting-out behaviour, and were abusive towards others, including being sexually abusive. The life histories of the participants reflected that parents failed to provide adequate care for a variety of reasons that may be related to deprivation and loss in their own childhoods, to adulthood mental disorders such as depression, substance use, or to the experience of severe life stresses compounded by external structural factors such as unemployment and poverty. In summary, the families of adolescent sex offenders can be described as disturbed, with a high rate of violence (both physical and sexual) and substance abuse. Most adolescent sex offenders come from single-parent homes or have been separated from their parents (Winokur et al., 2009).

The extended family: inter-generational patterns of abuse

Other issues that emerged in the cases were the negative impact of the extended family and intergenerational patterns of sexually abusive behaviour.

"Everyone in my father's family seems to own pornographic material: my father 's father, my father and his brother and the two grandsons. All of them are similar, as they are alcoholic, aggressive and unreasonable, and watch pornographic material. I feel embarrassed that my grandfather still hits my father and he just accepts it." (Jay)

According to the mother, the paternal grandfather was very aggressive and Jay's father could not see that he was following in the same footsteps. The paternal grandmother was disturbed and depressed; "she has a 'screwed' neck, collapsing muscles, is moody, and is like a nervous wreck" according to Jay. Jay's grandfather had assaulted Jay's father repeatedly, but he was passive and did not respond. All Jay's paternal uncles were aggressive, alcoholic and introverts.

All the patterns of behaviour in the extended family appeared to be similar, with the marked presence of alcoholism, sexual abuse or exposure to pornographic material, instability, inconsistent discipline, depression, and physical and emotional abuse. Hence family environments most likely to produce adolescent sexually abusive behaviour are characterised by instability, poor emotional bonds between the parent and child, early exposure to sexual material and behaviour, a high-risk environment for sexual abuse or sexual exploitation, and poor resources to cope (Barbaree & Langton, 2006). One expression of tension is violence, and one target of the violence is a child. The data in this study indicate that if families are dysfunctional from generation to generation, this may manifest in sexual offending or some other maladjustment to meet unfulfilled needs, unless individuals are helped to break the chain. The juvenile sex offender's role in the family had often been to act as a receptacle for negative feelings in the family, especially shame, guilt, abuse and anxiety; and the sexual offending behaviour was probably a presenting symptom in a long history of acting-out behaviours.

James had been introduced to sex by his parents, and by his foster-parent, as a game and hence he did not find the experience frightening. He became sexualised and thought that it was normal to initiate sexual relations with his victims because they would find the experience and encounter pleasurable, as he did. He was confused and angry when he was reprimanded for his offending behaviour with two 6-year-old girls.

The experience of child neglect and abuse is often embedded in a larger pattern of dysfunction and in many cases environmental chaos, making it difficult to separate the impact of neglect from other environmental influences. Particular issues that are considered are poverty, violence, the influence of pornographic material and changing value systems. Poverty may exacerbate parents' inability to provide adequate care, but should not be thought of as a singular cause. There are various mezzo-level factors, such as levels of social cohesion and informal and community-based support systems, that can help families mediate the effects of macro-level factors such as poverty, discrimination and social exclusion. However, lower socio-economic status mothers are found to be less stimulating to their children and to put a higher value upon control through punishment. Families that are financially better prepared have more escape routes, which may be used earlier in the development of the violent pattern. In some instances material means may discourage violence by allowing relief through child care services or making the child feel rewarded with treats or purchases. But such relief does not always serve to avoid violence, as is evident in more affluent families in which abuse occurs.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The research elucidates the possible relationship between family dynamics and offending behaviour. If family dynamics are better understood, services can be targeted to enhance family functioning. Too often we respond to families that are experiencing crises rather than empower them to effect change in the long term. The study underlines the importance of addressing multiple issues of poverty, problematic family relationships, absent fathers, unresolved trauma, poor family and societal values, exposure to pornography, domestic violence and substance abuse. The research suggests that neglect of these issues may increase the likelihood of producing adults who repeat their own life experiences.

The adolescents in this study perceived the negative events in their lives as unpredictable and uncontrollable, which generated a sense of helplessness. This is especially important, as powerlessness is a contributory factor to offending behaviour, as the offending allows for some degree of power and control. The adolescents who experienced abuse used sexual behaviours as a tension-reducing mechanism, a source of nurturance, to regain feelings of personal power, or for pleasure and comfort. In some instances, sexual behaviour was normalised and not considered wrong.

The family does not exist in a vacuum and cannot be held solely responsible for the problems experienced by the adolescent. The influences of the environment and broader society must be acknowledged. Sewpaul (2005:318) poses the following bold question: "If external socio-economic, political and cultural factors are maintaining families in poor, dispossessed and helpless positions, how are such families expected to move toward independence and self-reliance within the same structural constraints?" External structural factors such as poverty, inequality, unemployment, lack of support systems, lack of education and infrastructure, discrimination, social exclusion and violence have a way of penetrating the lives of families and individuals to manifest in a range of problems such as the substance abuse, domestic violence, and child abuse and neglect that social service practitioners have to deal with on a daily basis. This is no different in sexual abuse perpetuated by adolescent offenders. Thus, policies directed at challenging and changing these structural conditions must be developed to strengthen, support and enhance family life. This does not negate the need for direct services; indeed it should heighten awareness of the need for increased direct service, but with a radical and emancipatory thrust that emphasises the links between the personal and the political. The individual versus society is a false dichotomy as private troubles cannot be understood and dealt with outside of their socio-economic, political and cultural contexts (Dominelli, 2002; Mullaly, 2010). Our understanding of the relationship between the personal and structural factors does not mean that the adolescent is absolved of personal responsibility. The relationship between the individual and society is a mutually reinforcing one. As much as structural factors influence families and individuals on a micro level, individuals have agency to alter their values, beliefs and behaviours, and to influence societal consciousness and practices.

The socio-political climate in South Africa contributes to the increasing incidence of sexual offending. Violence, which characterised the country during apartheid, has escalated in different forms, with South Africa "teetering on the abyss of systemic, endemic corruption, where political cronyism has threatened the very foundation of long-term development" (Mills, 2011:285-286), thus institutionalising moral degeneration and violence. Many South African adolescents are exposed to violent experiences and when they are replicated within the family, coupled with sexual abuse, without the family's buffering and protective effects, the accompanying emotions can be traumatising. Children exposed to violence are likely to perpetrate acts of violence, and sexual offending is a violent crime. The adolescents had been systematically socialised to perceive violence and sexual control as a means to assert themselves.

The results of this study highlighted the importance of integrated and comprehensive intervention, including the need for therapeutic intervention with offenders and their families. Therapeutic services must focus on the essentials of mastery, empathy and growth, disrupting inter-generational patterns of neglect and abuse, and instilling a genuine concern for others; getting them to understand and to undo the impacts of external influences in their lives; resocialisation, re-education and cognitive restructuring at the level of the family and the individual. As sound, skilled therapeutic intervention is directed at preventing recidivism, it can constitute primary prevention for potential victims. Research has reflected success with therapeutic intervention with adolescent sexual offenders. Interventions broadly based on a cognitive behavioural framework, with a strong relapse-prevention element, are supported in the literature for work with children and their carers (Winokur et al., 2009). We must also engage in comprehensive primary preventive measures. Prevention must take a wider, community-based approach with large-scale educational programmes on what constitutes healthy versus abusive sex, gender role socialisation and its effects, inter-generational patterns of abuse and violence, and the harmful effects of sexual abuse on victims. We need to open up spaces for dialogue and debate around competing and conflicting societal values around gender and sexuality, and the roles of the media and the internet. A disturbing finding from this study was pornography being an immediate precipitant of adolescent sexual offending, along with the easy access that adolescents have to pornographic material. We need to have wider debates around issues regarding freedom of expression, access to information and the moral regeneration of society. These efforts must be combined with appeals to the conscience and humanity of people to respect fellow human beings.

Broad structural changes aimed towards achieving a more equal, just and peaceful world are necessary and social workers must advocate for such changes. While we pursue these utopian ideals, on a more immediate level intervention must begin with families that appear to be even remotely at risk. Indeed all families should be provided with primary preventive programmes such as family life education, with prevention beginning with paediatric support regarding parents' responsiveness towards infants and children, and with external resource mobilisation when necessary to buffer the effects of structural constraints. Children need to receive approval, physical attention and sexuality education from their parents, with fathers especially providing appropriate modelling for boys. The lack of a warm, affectionate father figure appears to be an important contributory factor to offending behaviour. As adults, parents and educators we need to feel comfortable and understand the dynamics of children's sexuality and communicate this to them appropriately. If we don't, children will turn to other resources, for instance, unhealthy peer influence and pornography, with devastating consequences as highlighted in this study.

REFERENCES

BARBAREE, H.E. & LANGTON, C.M. 2006. The effects of child sexual abuse and family environment. In: BARBAREE, H.E. & MARSHALL, W.L. (eds) The juvenile sex offender (2nd ed). New York: Guilford Press, 58-76. [ Links ]

BORDUIN, C.M., MUNSCHY, R.W., WAGNER, D.V. & TAYLOR, E.K. 2011. International perspectives on the assessment and treatment of sex offenders: theory, research and practice. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

BRIGGS, F. 1995. From victim to offender: how child sexual abuse victims become offenders. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd. [ Links ]

COYNE, I.T. 1997. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26:623-630. [ Links ]

DENNISON, S. & LECLERC, B. 2011. Developmental factors in adolescent child sexual offenders: A comparison of non-repeat and repeat sexual offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(11):1089-1102. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT. 2008. Child Justice Act 75 of 2008. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

DOMINELLI, L. 2002. Anti-oppressive social work theory and practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

HAGELE, D.M. 2005. The impact of maltreatment on the developing child. NC Med J, 66(5):356-359. [ Links ]

HUNTER, J., FIGUEREDO, A., MALAMUTH, N. & BECKER, J. 2003. Juvenile sex offenders: towards the development of a typology. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 15:27-48. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://link.springer.com/ article/10.1023/A:1020663723 593#page-1 [Accessed: 17/08/2013].

JEWKES, R., NDUNA, M., JAMA SHAI, N. & DUNKLE. K. 2012. Prospective study of rape perpetration by young South African men: incidence and risk factors. [ Links ][Online] Available: http: //www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fiournal.pone.0038210 [Accessed: 17/08/2013].

LANNING, K.V. 2001. Child molesters: a behavioral analysis for law-enforcement officers investigating the sexual exploitation of children by acquaintance molesters.Virginia: National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.ccoso.org/library%20articles/Lanning%20-%20molestor%20behavior%20analysis.pdf [Accessed: 17/08/2013].

MILLS, G. 2011. Why Africa is poor and what Africans can do about it. Johannesburg: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

MULLALY, B. 2010. Challenging oppression and confronting privilege. Ontario: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

OATES, K. 2007. Invited commentary juvenile sex offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(7):681-682. [ Links ]

O'HALLORAN, M.C.A. & O'REILLY, G. 2002. Psychological profiles of sexually abusive adolescents in Ireland. Child Abuse and Neglect, 26(4):349-370. [ Links ]

PETERSEN, I., BHANA, A. & McKAY, M. 2005. Sexual violence and youth in South Africa: the need for community-based prevention interventions. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(11):1233-1248. [ Links ]

RECKDENWALD, A.M.C. & BEAUREGARD, E. 2013. The cycle of violence: examining the impact of maltreatment early in life on adult offending. Violence and Victims, 28(3):466-482. [ Links ]

SEWPAUL, V. 2005. A structural justice approach to family policy: a critique of the draft South African Family Policy. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 41(4):310-322. [ Links ]

SMALLBONE, S.W. 2005. Attachment insecurity as a predisposing and precipitating factor for sexually abusive behavior by young people. In: CALDER, M.C. (ed) Children and young people who sexually abuse: new theory, research and practice developments. Dorset, UK: Russell House, 6-18. [ Links ]

VIZARD, E.H., HICKEY, N., FRENCH, L. & McCRORY, E.J. 2007. Children and adolescents who present with sexually abusive behaviour: a UK descriptive study. Journal of Forensic Psychology and Psychiatry, 18(1):59-73 [ Links ]

WINOKUR, K.P.H., DEVERS, L.N., HAND, G.A. & BLANKENSHIP, N. 2009. Child on child sexual abuse needs assessment: a literature review. Department of Children and Families. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://childonchildsexualabusepreventiontaskforce.intuitwebsites.com/FinalChild-OnChild Sexual Abuse NeedsAssessmentLiterature Review2.pdf [Accessed: 17/08/2013].

WORLING, J.R. & CURWEN, T. 2000. Adolescent sexual offender recidivism: success of specialised treatment and implications for risk prediction, Child Abuse and Neglect, 24(7):965-982. [ Links ]