Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.1 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-15

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-15

Informing employee assistance programmes for farm workers: An exploration of the social circumstances and needs of farm workers in the Koup

Jacolise Botes; Marichen van der Westhuizen; Nicky Alpaslan

Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Agriculture plays a pivotal role in human survival in terms of satisfying basic needs, specifically referring to the provision of food. A report by the International Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations indicates an estimated threefold increase in the need for grain over the next 30 years, and that countries will need to import five times more meat to provide globally for approximately 800 million people who are chronically underfed (Diouf, 2002:11-28). Agriculture, and more specifically the farm worker community, play a vital part in this regard.

With reference to farm workers in South Africa, Atkinson (2007:3) refers to this group as a neglected segment in society; they are an almost powerless, invisible group of people with a lack of a public profile. In this regard, the Human Rights Watch (2011) issued a report that placed the focus on continued abuses on farms in the Western Cape. This group only became "visible" during the recent strikes of farm workers. Although the strikes dealt with this aspect, the industry suffered losses and certain social concerns were raised, such as families who did not have food on the table during this time and children who were prevented from attending school (Davis, 2013).

The current social and economic problems faced by South African farm workers stem from a long history of, among other factors, colonialism, segregation, apartheid and, more recently, post-apartheid perceptions and marginalisation by political and economic power bases (Atkinson, 2007:4). The plight of farm workers is embedded in the way this sector of the South African population developed from the "master and servant" system. This involved a process that moved through the extension of labour laws to farm workers, the establishment of minimum wages, the provision of services in rural areas to the vocational direction of farming that evolved in recent times (Kleynhans, 2007:2). Research on the legacy of dependence and powerlessness among farm workers in the Western Cape in 2008 suggests that alcohol abuse has become a habitual lifestyle (Falletisch, 2008). That study found that this leads to a neglect of responsibilities related to homes, families and work. In line with this finding, Goodman (2007:64) notes a relationship between substance abuse, crime and poverty; and Patel (2005:189-198) found that substance abuse has negative consequences for productivity, economic growth, health and family life. Patel stresses that substance abuse poses a higher risk to development in remote rural areas, and suggests that these areas should be specifically targeted for the delivery of social services.

This study was conducted in the Koup, situated in the Western Cape and is one of the 34 districts in South Africa. The word "Koup" is derived from the Khoi-Khoi word "Goup", meaning "nice piece of fat around the stomach of a lamb". It refers to the fertility of this region. On the other hand, the Korana pronounced the word "Ghoup" in a different dialect, and that pronunciation means "skeleton", which indicates drought years when the field is very dry and full of bones. Both names are descriptive of this vast region of extremes which, after long periods of drought, quickly flowers profusely and brightly again after good rains. Although the Koup extends broadly from the Matroos Mountains near Touws River, north to the Nuweveld Mountains of Beaufort West and South, eastwards to the Great River Mountains of Willowmore, the centre or heart of the Koup district is located within a radius of 60 kilometres from Laingsburg, Merweville, and Prince Albert (Le Roux, 2003:5). The Koup District Agricultural Society (Koup DLV) includes members of agricultural associations from Laingsburg, Klein Swartberg, Prince Albert, Merweville and Leeugamka. Agriculture forms the core of the Koup and another feature of this area is that most of the farms are geographically isolated and far from villages or towns. The main income of farms is derived almost exclusively from small livestock, while seed production, deciduous fruit exports and viticulture are present to a lesser degree (Du Plessis, 2010). A total of 169 farm owners out of the total of 199 in the Koup are members of AgriSA. This agriculture organisation has issued two policy statements regarding the improvement of social welfare of farm workers: (1) the need for sound family values as a prerequisite for overall social development and economic growth; and (2) the creation of development opportunities to enhance life skills (Van der Westhuizen, 2010:47).

Social service delivery in remote rural areas such as the Koup, and thus to farm workers, poses special challenges (Schenck, 2010:16). Factors impacting on social service delivery, and therefore hampering development, include: (1) apathy, poor motivation, mistrust and lack of cooperation and communication between community members; (2) lack of adequate and sustainable funding of projects; (3) vast distances between the homesteads; (4) lack of transport; and (5) lack of capacity to manage the affairs of a community project (Gumbi, 2006:3-5). Based on the White Paper on Social Welfare (Ministry for Welfare and Population Development, 1997) social work in South Africa moved towards community-based developmental interventions on local levels. Atkinson (2007:203-227) elaborates on this and states that it is essential for local municipalities to become involved in service provision to farm workers in terms of basic service delivery, transport, health care, housing, education and social services (Atkinson, 2007:213).

The Basic Conditions of Employment Act (Act No. 75 of 1997) provides guidelines related to the requirements for employment of farm workers. In addition, the Labour Relations Act (Act No. 66 of 1995) aims to promote social justice, economic development and labour peace. A further aim of this legislation is to provide farm workers with a platform to express their concerns and opinions, and to participate in decision-making processes. Since 2004 annual farm worker summits have been held in the Western Cape with the goal to link farm worker communities to stakeholders.

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND MOTIVATION FOR RESEARCH

Farm workers are acknowledged to be a vulnerable group of people. Despite this acknowledgement and various pieces of legislation aimed at protecting farm workers, social service delivery to farm workers in remote areas such as the Koup is limited. This lack of services is attributed to the vast distances between farms and villages or towns. Recent studies focused on the social needs of farm workers (Bozalek & Lambert, 2008; Falletisch, 2008; Gumbi, 2006; Makofane, 2006) or on EAP as a tool in the social work profession in general (Brink, 2002). However, there is a gap in the literature having to do with research findings on EAPs for farm workers. Within the framework of farm workers as employees, employee assistance programmes (EAPs) offer a possible solution to the continued lack of services and development opportunities to these farm workers. However, it is necessary to explore the unique needs of farm workers before the content of such programmes can be developed. It was envisaged that this research study could contribute to the knowledge base of occupational social work in order to enable social workers to develop EAPs to farm workers.

The following section will provide the theoretical context of this study.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

"Employee assistance" and "employee wellness" are both terms described by the Employee Assistance Professionals Association of South Africa (EAPA-SA, 2009:9-11). According to this document, employee assistance is described as the employer organisation's programme based on core functions to enhance employee and workplace effectiveness through prevention, identification and resolution of personal and productivity issues. Employee wellness, on the other hand, is considered to be a state where employees are in good shape (mentally and physically), resulting in high levels of productivity. A distinction is made between the role of an EAP professional, who must be a professionally trained person practising independently and performing clinical EAP-specific or related tasks (i.e. therapy or counselling), and an EAP practitioner, who must be a trained person to coordinate EAP-specific or related tasks (i.e. referral, liaison, training, marketing and evaluating), while requiring minimum supervision.

From a social work perspective, an employee assistance programme, as a specific method of service delivery, is a programme or service offered by employers to employees to prevent, alleviate or eliminate employment and social problems in order to promote job satisfaction, productivity and overall social functioning (New Dictionary of Social Work, 1995:72). EAP is mainly implemented within the sphere of occupational social work, a specialised field within the social work discipline which includes social work services to employees who are committed to a working sector (Mogorosi, 2009:343-344). The rationale for EAP is often derived from the following aspects: any productivity problems associated with personal problems such as substance abuse, health, emotional well-being and life skills. These personal problems result in absenteeism, loss of productivity, poor labour relations, employment termination or reappointment. This field furthermore typically provides prevention services to employees (also often including their families) within the workplace with respect to conflict management, assertiveness, working mothers' issues, personal money management, trauma counselling, HIV and AIDS, and stress in the workplace (Terblanche & Taute, 2009:xiv). The National Strategic Plan of the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Department of Agriculture, 2009-2010:28-29) provides the most recent guidelines for the use of EAPs in the agricultural sector. It is proposed that EAPs should focus on issues such as substance abuse, financial difficulties, and HIV and AIDS. The way to address the above issues may be through counselling and prevention programmes regarding substance abuse, financial well-being programmes, and HIV and AIDS prevention and counselling. The value of EAP in South Africa, and specifically in the agricultural set-up, stems from a long history of labour and industrial relations (Giliomee & Mbenga, 2007). The changing socio-political environment of South Africa provides to EAPs a certain set of priorities which includes more than the "traditional" set of programmes that are internationally used. Maiden (2004:11) mentions that it will take generations to remove the social problems created by apartheid, but that those problems need to be addressed in post-apartheid South Africa to minimise the degree of psychological trauma for all South Africans (post-traumatic stress disorder of an entire society). The author states that EAP can play an important role in this regard.

Social work interventions to promote employee wellness within EAP can range from the micro level (single system) to the macro level (community level). Services can be related to problems such as HIV and AIDS, or alcoholism. These services are seen as a single-service orientation, or so-called "worker-as-person" approach. A more comprehensive service will be necessary when initial problems are linked to other underlying problems in the workplace. Such programmes will entail some educational programmes and consultations on management level. Prevention services can also be performed. Educational programmes are launched for employees to inform and help them take responsibility for their own physical or mental health. Organisational intervention can take place when the "person-as-worker" is seen in terms of how his/her problems could affect productivity. Changes in production structure are aimed at certain organisational structures to accommodate the "person-as-worker". Finally, the workplace functions as a community which incorporates both the employer's and employees' goals as they strive together to achieve them. A particular value orientation involves all stakeholders to bring about change (Maiden, 2004:34-35).

The South African Professional Employee Assistance Association operates mainly with reference to three documents offering services within a dynamic framework: (1) the constitution of the EAPA, (2) the ethical code of the EAPA and (3) the standards of the EAPA. These services are then acquired by one of the following:

- The utilisation of service providers as appointed staff within an industry;

- The contracting of independent service providers on a contract basis to provide services as needed;

- The use of organisations that specialise in offering the whole package of EAP (Blackadder, 2010.)

THE RESEARCH QUESTION AND GOAL

The research question which guided this study, which was exploratory, descriptive and contextual in nature, was formulated as follows: What are the social needs among farm workers in the Koup that could be dealt with through EAPs?

The goal of this research study was: To develop an in-depth understanding of the social needs of farm workers in the Koup that should be dealt with through employee assistance programmes based on the perspectives of the farm workers.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The qualitative research approach was seen as suitable for this study, as it provided a framework within which the "pure experiences" of the participants could be explored to develop an insight into issues that would lead to improved and relevant intervention strategies (Berrios & Luca, 2006:184). This qualitative research study was conducted within the framework exploratory, descriptive and contextual research designs.

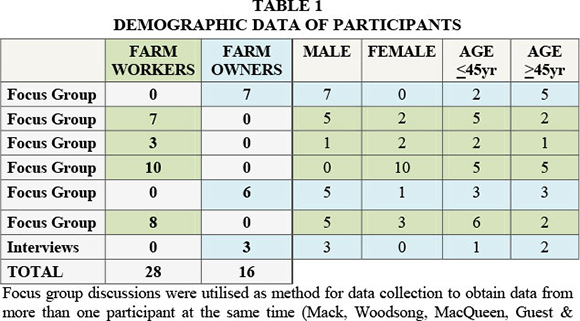

The population for this study was all farm workers in the Koup, while the inclusion criteria narrowed the focus down to all full-time farm workers in the Koup. The purposive sampling technique (as a technique used in non-probability sampling) was adopted to seek typical and divergent data from farm workers from different agricultural societies in the area. The criteria for inclusion were: (1) all full-time farm workers and (2) all farm owners and/or managers in Central Koup. Members (farm owners) of the Koup Districts Agricultural associations (KoupDLV) were asked to provide access to farm workers. Within the context of the qualitative nature of this study, the sample size was determined by data saturation, which was detected after six focus group discussions were conducted with a total of 28 farm workers. The demographic details of the participants are indicated in Table 1 below.

Focus group discussions were utilised as method for data collection to obtain data from more than one participant at the same time (Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest & Namey, 2005:51). The following questions contained in an interview guide were put to the participants once they agreed to participate:

- Tell me about the circumstances of farm workers on farms in the Koup.

- Tell me about your life on the farm.

- Tell me about your work as farm worker on this farm.

- What are the personal problems experienced by the farm workers here on the farm?

- What circumstances and problems (i.e. personally, at home and work-related) in general affect farm workers' ability to do their work on the farm?

- What personal circumstances (i.e. personally, at home and work-related) affect your ability to do your work on the farm?

- What do farm workers do to solve their problems?

- Where do farm workers go to get help with their problems?

- Any advice/suggestions on how the problems of farm workers can be addressed and by whom they should be dealt with?

The focus group discussions were recorded (with the permission of the participants) and field notes were taken by the researcher responsible for the fieldwork. Transcripts of the recordings and field notes were made directly after the focus group discussions. The transcripts were analysed into themes and sub-themes using a coding system according to the step-wise framework proposed by Tesch (in Creswell, 2009:186). Guba's model for data authentication (in Krefting, 1991:214-222) was used for data verification. It focused on: (1) the validity of the truth through employing various interviewing techniques, (2) applicability through a compact description of the methodology and the purposive sampling technique, (3) consistency through a compact description of the methodology, and (4) neutrality through using extensive transcripts and field notes, and using an independent coder.

Ethical considerations included that confidentiality should be enhanced by ensuring that privacy was respected by maintaining anonymity in the transcripts of the focus group discussions. The members participating in each of the focus groups also signed a document in which they vouched to keep the information shared in the focus groups confidential. Digital information was used only for transcription purposes and then destroyed. The transcripts and notes from the research were also stored in locked files that only the researchers had access to. Participants gave their informed consent to participate in this research and were informed beforehand about the reason and the nature of the investigations to ensure that they were not misled (Leedy & Ormrod, 2005:101). When sensitive issues emerged in focus groups, participants were referred to a local social worker to defuse their feelings and debrief as necessary. No incentives were given for participation and measures were taken to ensure that participants did not suffer inconvenience or discomfort during data collection.

Limitations experienced during the course of this study included geographical distance, because this placed certain demands on the researcher (conducting the fieldwork) in terms of transportation and time. All the participants spoke Afrikaans (an indigenous language typically spoken in this area); therefore the perceptions and experiences of other cultural groups were not explored. The current South African agricultural and political situation involves controversial issues on labour practices and laws, which consequently resulted in resistance to participation. Apathy and in some cases a poor response to the call to participate in focus groups were experienced as further challenges in the research.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Of the 28 farm worker participants, 11 were male and 17 female. Most farm worker participants (18) came from the age group younger than 45 years. During this development stage (the adult years) the inner self, the family, the work setting and the community become important aspects to master. Participants younger than 35 (10) were involved with the developmental tasks of early adulthood, including job settlement, finding a place in the community and establishing an identity, values, significant interrelations and a household with a spouse and raising children (Louw & Louw, 2009:471-662).

The themes and sub-themes will be described next, together with verbatim quotations and a literature control. The verbatim quotations were translated into English. Three main themes provide the story line for the data obtained from the farm workers, namely: (1) their experiences and perceptions of living and working on farms; (2) relationships between farm workers themselves, and between farm workers and employers; and (3) their perceptions and experiences of resources and support to be addressed through EAPs.

Theme 1: Farm workers' experiences and perceptions of living and working on farms

The first sub-theme of this theme relates to the experiences and perceptions of the farm worker participants regarding their living on the farms, while the second sub-theme relates to experiences and perceptions regarding working on the farms.

Sub-theme 1.1: Participants' reported experiences and perceptions of living on farms

The participants reported that they valued the tranquillity, peacefulness and safety of living on farms, and added that they received benefits that contributed to an affordable lifestyle. The following verbatim descriptions attest to this.

"I grew up on the farm, so the peacefulness is nice for me."

"It is quiet on the farm. In town there is always a lot of noise."

"You can walk where you want to."

Being in a "tranquil" or "restful" environment allows individuals to cope with the challenges of life, and contributes to enjoyment of life and mental and physical health (Lechtzin, Busse, Smith, Grossman, Nesbit & Diette, 2010:965-972). Tannerfeldt and Ljung (2008:35,42) confirm that safety is an important asset in rural life. The authors assert that safety in urban areas, on the other hand, is becoming an issue of concern. The authors note that especially the poor (living in urban areas) have identified safety and security as a major concern, just as important as hunger, unemployment and lack of safe drinking water.

In addition, the participating farm workers reported that living on the farms is affordable and has benefits. They stated the following:

"You can get wood, and you do not have to pay for it. "

"It is much nicer on the farm than in town, because there you have to pay for water and electricity. "

"And meat and vegetables. We get this for free on the farm."

Although the participants mainly reported that living on farms is experienced and perceived as positive, one participant reported that people living on farms are labelled by people living in towns, and that it is perceived as a negative experience. The participant described this aspect as follows: "Once you live on a farm it is difficult to then go to town, because people keep on asking you what you are doing there and say you must go back to the farm."

Sub-theme 1.2: Participants' experiences and perceptions related to farm work

The participants expressed that they enjoyed the type of work that they do on the farm, as illustrated by the following statements:

"I like my work on the farm, it is nice work."

"I am able to work every day and the hours are good."

"To me my work means a lot, I am happy to have work. I do not want to live in town and then I cannot find work."

In line with the participants' developmental stage, work in general is important, because apart from the economic value of work, it contributes to an individual's identity. Many adults answer the question "Who are you?" in terms of their careers, and work is a way in which individuals satisfy many of their psychological and social needs (Louw & Louw, 2009:471-662).

Participants reported that they valued the experience that they gained from working on the farms.

"There is always something new that you will learn. So I like to learn new things."

"I like the experience that I get on how to feed animals and how to look after them."

Explaining the learning that takes place in the working environment, Race (2005) refers to Kolb's (1984) model for the adult learning process. According to this model, the working experience results in a knowledge base developed through observation and conceptualisation (i.e. making sense of what one experiences), and then leads to the active implementation of the new knowledge through an experimenting process.

Apart from gaining work experience, one participant noted how her work on the farm contributes to her personal growth as follows: "I work in the kitchen. I am a mother and at the house I learn a lot of things about being a mother and a wife. I talk a lot to [name of the employer] and she gives me advice and says I am a very good cook."

The workplace could also help a person to develop a healthy self-concept from two main resources: (1) the feedback one receives from employers, and (2) the behaviour or skills one possesses to undertake the work assigned to you (De Klerk & Le Roux, 2008:71).

While this theme revealed a primarily positive experience of living and working on farms, the relationships appeared to be more problematic, as will be discussed in the next theme.

Theme 2: Relationships between farm workers and between farm workers and employers

This theme is divided into two related sub-themes presented below.

Sub-theme 2.1: Participants' experiences and perceptions related to relationships between the farm workers and the farmers

The participants reported that they sometimes experienced strain in the employer-employee relationships, while perceiving communication as a contributing factor in this regard. The following statements attest to these experiences and perceptions:

"Sometimes the farm workers and the farmers do not get on well."

"Maybe the farmer does not feel so well and then I ask something and he bites my head off."

"We must get on well with the farmer, because we work together every day. For that we must be able to talk to each other."

In traditional employer-employee relationships communication was used only as a tool to convey information, to acquire information and to provide feedback. Communication in modern times should rather be used as a learning tool that enables and enhances the adult learning process. Effective communication between the employer and employee can give direction to the learning process, as well as to ensure that instructions are understandable (Meyer, 2007:105-111; Radiboke, 2010:7).

In conclusion to this theme, one participant reported that the relationships among farm workers themselves and with the employers are not only strained, but that positive relationships also exist: "I am proud to say that I have a good relationship with my neighbour and his wife, and I also get along well with the farmer, I can talk to him."

Sub-theme 2.2: Participants' experiences and perceptions related to interrelationships among farm workers

The following statement reveals that conflict between farm workers exists:

"There is always someone who causes trouble, there is always a fight going on."

The participants' comments indicate that they experience an interrelatedness of personal and work relationships among farm workers and that this has an impact on their productivity. The following statements provide an indication of these experiences and perceptions:

"We cannot keep on fighting so much, because we have to work together, and sometimes you stay away from work because of this."

"Sometimes you fight at work, and you live next to one another, and then you must still see each other at home."

The reasons for and interrelatedness of conflict between the farm workers' daily lives and working lives were summarised as follows by one participant: "Jealousy over women, or if you got a compliment from the farmer... "

Louw and Louw (2009:544-549) discuss Erikson's theory of development and stress the importance of mastering the building of close relationships with others. Adults have to develop an ability to give up some of their own desires in order to form intimate relationships. It is important, however, that individuals first establish a personal identity before they establish a shared identity with another person.

The farm worker participants also referred to resources for service delivery and support that are available to them, or that are lacking, in the context of their experiences of living and working on farms. These experience-based perceptions will be discussed in the next theme.

Theme 3: Farm workers' perceptions and experiences about resources available and their needs for support services to be dealt with through EAPs

In this theme, the farm worker participants referred to service delivery resources and support lacking in their lives. They referred to employers as the main source of support. They were able to identify specific areas where resources and support services are needed.

Sub-theme 3.1: Farm worker participants' experiences and perceptions point to a lack of knowledge about and access to resources and support available

To the question "Who helps you when you experience problems? the participants were not able to provide a clear answer. One participant attempted to answer this question as follows:

"Upstairs. Only God."

Another participant referred to an officer at the local Advice Office, but was not able to describe what this person could help with:

"The man at the Advice Office is there in the mornings, I think it is for when you lose your job ... No, he is a politician and people go to him for work things ... Or I do not really know."

The participants referred to the employer as the first support system to advise them on matters, as well as to give them practical support.

"The farmer is the first one I go to for help."

"When we need transport for the children, then we go ask the farmer."

With regard to this theme under discussion, Atkinson (2007:164-166) confirms the reliance on the employers as a support system. The author relates this to the fact that, during the 1980s, the social order was one of paternalistic responsibility for farm workers; this resulted in a micro welfare system in which the effect of relatively low wages was partially offset by private welfare contributions and the provision of infrastructure services by the farmers.

Sub-theme 3.2: Experience-based perceptions related to spiritual support and the involvement of churches in farm workers' lives

Allender (2003:50) describes the human need for some form of religion as an "oscillating pattern through generations". However, the statements below point towards a lack of, or very limited, spiritual support provided to farm workers today:

"No, not often. Our church leaders we only see when they collect money and then they are finished with you."

"On our farm we have farm church services, but not every Sunday."

Linking to the statements above, a participant expressed the opinion that regular church meetings could have the added value of access to spiritual support and contact with the church minister/reverend. The participant said: "Then the reverend or the deacon can talk to you there at the church ... If someone can help me to give my life to God, then I can get away from all the wrong things and my life would be better."

Sub-theme 3.3: Experience-based perceptions in relation to the involvement of social workers in farm workers' lives

The participants expressed a need for personal support by way of a social worker who visits them as a family through the following statements:

"If they can come to you and give you advice, for instance, when you fight with your wife or with the farmer and that person can help you to make things right."

"Then you will also feel like you are being seen."

Social services assist clients to achieve their personal goals and gain greater insight into their lives. The result should lead to a greater degree of satisfaction with the individual's life. It is, however, not a process where the social worker tells the client what he or she should do, but rather to provide support to find solutions for problems (Harris, 2011). Farley, Smith and Boyle (2006:7-10) note that the basic aim of social work is to help clients to help themselves or to help a community to help itself. The emphasis is on the importance of family in moulding and influencing behaviour.

The participants explained their perceptions related to the role of social workers as follows:

"Social workers are more there for people whose pay is taken away or whose children are taken when they do not look after them."

"They look at children who are walking on the wrong road and see what goes on at the house."

Furthermore, the farm worker participants reported that they have limited contact with social workers.

"I have never seen one."

"The social workers do not come to the farm. They visit the town, but not often."

"Sometimes they say they will be in town this day, and you go, but then they do not come."

The national goals of the White Paper on Social Welfare in South Africa (Ministry for Welfare and Population Development, 1997) are to render services to all South Africans, with specific emphasis on the poor and the vulnerable, and to ensure that services are developmental, preventative, protective and rehabilitative in nature. To explain the perceptions of participants described above, a research study done by Schenck (2004:184-190) indicates that working conditions of social workers from rural areas may impact on their visibility and accessibility to a community. Factors associated with working conditions that put a strain on social work intervention include availability of cars, functionality of vehicles for remote areas, office facilities and inability to use technology.

Sub-theme 3.4: Experience-based perceptions in relation to financial support and access to, or inaccessibility of, government services

The participants referred to government services and financial support available/not available in terms of programmes by IMBIZO (a traditional Zulu word meaning "a forum for dialogue discussion of policy between the government and the people"), social grants and housing.

"I went twice to a programme [by IMBIZO] for financial matters and learned quite a bit."

"I have health problems, but no one can help me with the right papers to apply for a grant."

"I have been struggling for years to get a house in town."

With regard to financial support, money management and government services, Falletisch (2008:96) elaborates that farm workers are nowadays indebted to shebeen (i.e. informal liquor stores) owners, loan sharks and furniture shops that offer lay-bys and long-term credit. The author asserts that farm workers over-commit themselves to various debtors to get them from one crisis to the next. There is little forward planning or delayed gratification.

In spite of the lack to access of government services, South African legislation makes provision for financial support and access to government services. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996 states in Section 27.1 (c) that "everyone has the right to have access to: (i) health care services, including reproductive health care; (ii) sufficient food and water; and (iii) social security, including, if they are unable to support themselves and their dependants, appropriate social assistance". The South African Social Security Agency Act (Act No. 9 of 2004) provides for the establishment of the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) as an agent for the administration, management and payment of social assistance, to provide for the prospective administration and payment of social security, including the provision of services related thereto. In addition to the above legislation, the White Paper on Social Welfare (Ministry for Welfare and Population Development, 1997) advocates a comprehensive and integrated social security system, which would include social assistance and social insurance with co-responsibility between employers, employees, citizens and the state to ensure universal access and coverage of social security (Patel, 2005:124-125).

Concluding this sub-theme, the participants also reported that they perceived emergency support to the employer as part of the government's responsibility to them through the following statement:

"And why can the government not help the farmers when it is so dry? Then we can all survive until the rain comes. "

Sub-theme 3.5: Experiences related to health care

In contrast to the right of all citizens to health care enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996, as mentioned in the former sub-theme, the participants reported that health care services were often lacking on the farms, and that access to health care was experienced as a challenge. The following storylines testify to this:

"The clinic bus only goes to one farm."

"You must go to town to the clinic and then wait for a doctor or make an appointment."

In an effort to deal with the reported lack of access to formal health services, one participant's response also indicated she resorted to self-medication, as she reported that she uses home remedies to provide health care for family members: "She [the farmer's wife] gives me 'wynruit ' and 'oondbos ' and then I make a tea to give to my husband. It is advice from the old people. And you can take 'peperboomblare ' and put it on your head for a headache. And you put 'dassiepis ' on your back for back pain."

Sub-theme 3.6: Farm workers need assistance regarding relationships

Regarding interpersonal relationships, the participants reported a need to be assisted with both personal and work-related relationships. The following statements attest to this:

"If your wife is angry at you, and you go to work then you worry about going home."

"People need help with problems between the wife and the husband."

"How do you start a home life when you are young? "

"When I got divorced I had nobody to tell me how to do it and what I must say."

"We need help to make sure we have good relationships with the farmers, to communicate well and that he can tell us if something is wrong, or we can ask questions."

Conflict management as a skill to handle interpersonal problems was highlighted in the following comments:

"When our people fight they want to hurt one another, like throwing boiling water at a person."

"If there are bad feelings between us, then one will say to the other one I will get you and then one day he comes with a knife. People do not know how to make peace."

Conflict is a normal and necessary part of healthy relationships. The importance of learning how to deal with conflict, rather than avoiding it, is therefore emphasised. On the one hand, when the inevitable conflict is mismanaged, it can harm the relationship; on the other hand, when handled in a respectful and positive way, conflict provides an opportunity for growth, ultimately strengthening the bond between two people (Segal & Smith, 2010).

Sub-theme 3.7: Farm workers need assistance regarding substance abuse

Falletisch (2008:3) summarises habitual alcohol abuse over weekends among farm workers as follows: "The infamous 'tot' system initiated by Jan van Riebeeck and continuing late into the twentieth century has enslaved many labourers in a cycle of habitual drinking, social violence and poverty. Habitual drinking has become the norm on farms, a weekend ritual that few labourers manage to escape."

The participants highlighted the need for assistance with substance abuse by referring to its impact thereof:

"I mean, if my wife comes home and I am drunk, she is not happy and then we fight again. So is this drinking thing again ".

"A lot of the fighting is because of the drinking".

"No, we are not angry at each other, only over weekends when we drink we start fighting and someone must help the people with this problem ".

"It is a big problem here. It ruins lives "

"Someone died in Laingsburg last week because of the drinking. This is a big problem that someone must help us with."

"I would like to be able to stop drinking."

"I try, but what must I do?"

"You decide to stop, but then your neighbour offers you a drink and you do not know what to do. "

Substance abuse leads to addiction and personal and social problems such as violence, crime and traffic-related trauma (Betancourt & Herrera, 2006:17). A study conducted by Mogorosi (2009:498-499) highlighted the fact that the abolishment of the so-called "tot system" has not significantly reduced the incidence of habitual excessive drinking among farm workers. This author notes that, whilst achieving sobriety is a key intervention in achieving social harmony, the outlook for sustained success is poor when dealt with in isolation from other social needs (e.g. financial problems, lack of interpersonal skills, etc.).

Sub-theme 3.8: Farm workers need assistance regarding relaxation and planning of free-time activities

The participants requested support and assistance to become skilled and involved in recreational activities, sport and cultural activities.

"Weekends is a problem, we need to learn to do other things. Maybe a place where everyone can watch TV? "

"I would like it if we can arrange things like dances and singing competitions. Then we can dress nicely."

"And if we can learn to organise sport events, with teams that can play against one another."

Atkinson (2007:207) points out that the general lack of recreational facilities available to farm workers is linked to the widespread problem of alcohol abuse on farms. As municipalities become increasingly responsible for recreation services, the author suggests that local governments need to promote the provision of recreational facilities to farm workers as well.

Sub-theme 3.9: Farm workers need assistance regarding child care and parenting skills

The participants reported that child care and parenting skills would be a valuable focus area for professional service delivery.

"Andhow to learn how to teach children the right way".

"I have two daughters and the oldest one already is giving me problems and I think the youngest one started drinking and I need advice how to handle them."

Parenting is described by Davies (2000:245) as the process of promoting and supporting the physical, emotional and social development of a child from infancy to adulthood. In terms of this description, support to farm workers regarding parenting skills refers to the activity of raising a child rather than the biological relationship.

While discussing the need for assistance to become better parents, one participant admitted that substance abuse is a contributing factor to the child care and parenting problems experienced by farm workers. He explained that he attempts to prevent this as follows:

"I try not to drink at home, or I drink and then walk away."

Sub-theme 3.10: Farm workers need access to support when trauma is experienced

Participants explained that they had no support during certain difficult times, and that they would have liked to be assisted in this regard.

"My parents died shortly after one another. It was very hard and I had no one to help me with this sadness."

"My son drowned and to this day I am still not over it."

Wood (2010) warns that untreated trauma could lead to a more devastating situation than the event that caused it. It's also possible for the effects of trauma to last for many years. The sooner that symptoms are dealt with, the more chance there is of a full recovery. Trauma counselling could help people face their emotions and overcome the difficulties they are going through (Wood, 2010).

Sub-theme 3.11: Farm workers need practical assistance regarding transport and housing

Considering the vast distances between the farms and towns, as well as the fact that the farm workers mostly live and work on farms, the participants also requested that transport and housing issues be dealt with. The following statements illustrate their views in this regard:

"The schools do not make provision for how the children must get to school."

"Our houses must still get electricity."

"Maybe someone can show us how to do maintenance on our houses."

Atkinson (2007:224) deals with farm workers' mobility and transport by indicating that there is a real need for some kind of organised (and possibly subsidised) transport system between the farms and the towns. The author is of the opinion that inadequate transport systems lead to numerous problems in people's lives.

CONCLUSIONS

Farm worker participants perceived living and working on farms as a source of tranquillity, security and material benefits (wood, water, food). They also described the benefit of gaining experience when working on farms. From the findings and the literature control, it seemed clear that the relationship between employer and employee still leaned towards a micro welfare system with a semi-paternalistic nature (Atkinson, 2007:164-166). Support systems that were identified as needed to support farm workers in dealing with social needs were:

- Health care/medical services in terms of accessibility;

- Social workers/psychologists to deal with trauma;

- Government agencies involved with social grants.

Aspects to be included in services to farm workers were identified as follows:

- Dealing with violence as a means to deal with conflict;

- Relationships, that is intrapersonal, interpersonal and employee-employer relationships;

- Spiritual support and involvement in church/religious activities;

- How to access and use social grants;

- Financial management;

- Personal support;

- Substance abuse;

- Parenting and child care;

- Support and assistance to have farm workers become skilled and involved in recreational activities, sport and cultural activities;

- Transport services between farms and towns to access support services and/or farm visits by support systems (i.e. health care and social services);

- Housing on farms and in towns.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to place the findings in the context of EAPs, the following recommendations are made: EAPs may be used by farm owners or other service providers (e.g. municipalities) to provide farm workers with a service to address their specific needs. Municipalities as an operational function for service delivery by government can play a major role in service delivery to farm workers regarding these needs (Atkinson, 2007:165-166). Partnerships between municipalities and farm owners could include farm owners as service intermediaries on behalf of municipalities, rather than deploying their own staff. EAPs could therefore be introduced by municipalities or farm owners could be supported (financially and practically) to introduce such programmes to farm workers. Service providers in private practice (e.g. registered EAP providers) could therefore be contracted to provide services to farm workers and to coordinate service delivery in a cost-effective manner (Atkinson, 2007:205-206). The authorities responsible for providing services to farm workers, as well as the farm owners and the farm workers themselves, could benefit from such an endeavour. The authorities will find a means to adhere to the requirements for social service delivery as described in the White Paper on Social Welfare (Ministry for Welfare and Population Development, 1997), while employee wellness will ensure that farm workers are in a good mental and physical state, resulting in high levels of productivity (EAPA-SA, 2009:9-11).

Based on the reported reality of vast distances, an appointed or contracted EAP service provider would have to be able to function independently. It is therefore recommended that such a service provider should be viewed as an EAP professional.

In terms of the structure or format of EAPs on farms, Du Plessis's (in Maiden 2004:34) proposed service delivery structures are recommended:

- Single service-orientation, related to some problems such as HIV and AIDS or alcoholism for the "worker-as-person";

- A more comprehensive service when initial problems are linked to other underlying problems in the workplace, including some educational/prevention programmes and consultations on management level;

- Organisational intervention when the "person-as-worker" is seen in terms of how his or her problems could affect productivity, focusing on changes in the production structure to accommodate the "person-as-worker";

- The workplace is seen as a community, incorporating both the employer's and employee's goals. All four of the above options include a particular value orientation that involves all stakeholders to bring about change (Maiden, 2004:35).

It is concluded that social work, within the context of occupational social work through EAPs, can play a specific role in terms of the development, planning, and execution of services to groups (in this case the farm workers) who experience a lack of service delivery (Farley et al., 2006:7-10).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article is a tribute to and in memory of Jacolise Botes, who was the primary researcher in this study. She passed away shortly after completing this project, and we hope that her wish to contribute towards alleviating the plight of farm workers will be fulfilled through the dissemination of the research results.

REFERENCES

ALLENDER, D.B. 2003. How children raise parents. Colorado: Waterbrook Press. [ Links ]

ATKINSON, D. 2007. Going for broke: the fate of farm workers in arid South Africa. Pretoria: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

BERRIOS, R. & LUCA, N. 2006. Qualitative methodology in counselling research: Recent contributions and challenges for a new century. Journal of Counselling and Development, 84:174-186. [ Links ]

BETANCOURT, O.A. & HERRERA, M.M. 2006. Alcohol and drug problems and sexual and physical abuse at three urban high schools in Mthatha. South African Family Practice, 48:17-19. [ Links ]

BLACKADDER, G. 2010. Employee assistance professionals association of South Africa. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.eapasa.co.za. [Accessed: 10/06/2010].

BOZALEK, V. & LAMBERT, W. 2008. Interpreting users' experiences of service delivery in the Western Cape using a normative framework. Social Work, 44(2):107-120. [ Links ]

BRINK, A. 2002. Die aanwending van werknemerhulpprogramme deur welsynsorganisasies. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (Unpublished minidissertation) [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2009 Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed). London: Sage Publishers. [ Links ]

DAVIES, M. 2000. The Blackwell encyclopaedia of social work. London: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers. [ Links ]

DAVIS, R. 2013. Farm workers' strike might be over but everyone is a loser. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2013-01-23-farmworkers-strike-may-be-over-but-everyones-a-loser#.UUWAqhdHLzw. [Accessed: 17/03/2013].

DE KLERK, R. & LE ROUX, R. 2008. Emosionele intelligensie. Cape Town: Human and Rosseau. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES, SOUTH AFRICA. 2009. National strategic plan 2009-2010. [ Links ] [Online] Available: www.daff.gov.za. [Accessed: 05/03/2010].

DIOUF, J. 2002. Towards 2010/2030. [ Links ] [Online] Available: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/004/y3557e/y3 557e.pdf. [Accessed: 10/06/2010].

DU PLESSIS, C. 2010. Agricultural Development Officer of the Department of Agriculture. Personal interview, Laingsburg (9 April 2010). [ Links ]

EAPA-SA. 2009. Standards for Employee Assistance Programmes in South Africa. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.eapasa.co .za/index.php/documents. [Accessed:10/06/2010].

FALLETISCH, L A. 2008. Understanding the legacy of dependency and powerlessness experienced by farm workers on wine farms in the Western Cape. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. (Unpublished MA thesis) [ Links ]

FARLEY, O.W., SMITH, L.L. & BOYLE, S.W. 2006. Introduction to social work. (10th ed). Boston: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

GILIOMEE, H. & MBENGA, B. 2007. Nuwe geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers. [ Links ]

GOODMAN, A. 2007. Social work with drug and substance misusers: transforming social work practice. Exeter: Learning Matters Pty/Ltd. [ Links ]

GUMBI, T A P. 2006. Conditions inhibiting and enhancing rural development projects in South Africa. Paper presented at the International Conference of the Association of South African Social Work Education Institutions. University of Zululand. [ Links ]

HARRIS, T. 2011. Counselling. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://ncmentalhealth.com/id3.html. [Accessed: 23/08/2011].

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH. 2011. Ripe with abuse human rights conditions in South Africa's Fruit and Wine Industry. New York: Human Rights Watch. [ Links ]

KREFTING, L. 1991. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3):214-222. [ Links ]

KLEYNHANS, K. 2007. Agri SA Newsletter, 9:2, 24 April. [ Links ]

LECHTZIN, N., BUSSE, A.M., SMITH, M.T., GROSSMAN, S., NESBIT, S. & DIETTE, G.B. 2010. Environment and behaviour. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(9):965-972. [ Links ]

LEEDY, P.D. & ORMROD, J.E. 2005. Practical research (8th ed). New Jersey: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

LE ROUX, P.J. 2003. Uit die Koup. Stellenbosch: Oewers Publishers. [ Links ]

LOUW, D. & LOUW, A. 2009. Adult development and ageing. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

MACK, N., WOODSONG, C., MACQUEEN, K.M., GUEST, G. & NAMEY, E. 2005. Research methods: a data collector's field guide. North Carolina: Family Health International. [ Links ]

MAIDEN, P.R. 2004. Accreditation of employee assistance programmes. Employee Assistance Quarterly, 19(1):11-35. [ Links ]

MAKOFANE, D. 2006. Factors affecting social development in rural communities. Paper presented at the International Conference of the Association of South African Social Work Education Institutions (University of the North). [ Links ]

MEYER, M. 2007. Managing human resource development: an outcome-based approach (3rd ed). Durban: Lexis/Nexis. [ Links ]

MINISTRY FOR WELFARE AND POPULATION DEVELOPMENT, SOUTH AFRICA. 1997. White Paper of Social Welfare, Notice 386 (18166). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

MOGOROSI, L. 2009. Employee assistance programmes: their rationale, basic principles and essential elements. Social Work, 45(4):343-348. [ Links ]

PATEL, L. 2005. Social welfare and social development in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

RACE, P. 2005. Making learning happen. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

RADIBOKE, S. 2010. Life skills courses. Die Wolboer, 7, April. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (RSA). 1995. Labour Relations Act (Act No. 66 of 1995). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (RSA). 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (RSA). 2004. Social Security Agency Act, (Act No. 9 of 2004). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

SCHENCK, C.J. 2004. Working conditions of social workers in rural areas. The Social Work Practioner-Researcher, 16(2):184-190. [ Links ]

SEGAL, J. & SMITH, M. 2010. Conflict resolution skills. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://helpguide.org/mental/eq8conflict resolution.htm [Accessed: 23/08/2011].

TANNERFELDT, G. & LJUNG, P. 2008. More urban less poor: An introductory to urban development and management. Malta: Gutenberg Press. [ Links ]

TERBLANCHE, L.S. & TAUTE, F.M. 2009. Occupational social work and employee assistance programmes: contributions from the world of work. Social Work, 45(4):Editorial. [ Links ]

TERMINOLOGY COMMITTEE FOR SOCIAL WORK. 1995. New Dictionary of Social Work. Cape Town: CTP Book Printers. [ Links ]

VAN DER WESTHUIZEN, E. 2010. Farm worker summits: what has Agri-Forum done for farm workers? Agri Farmer, 39(1): 1-5. [ Links ]

WOOD, B. 2010. Trauma counselling: Why it helps. [ Links ] [Online] Available: http://www.bryanwood.co.za/trauma-counselling-why-it-helps/ [Accessed: 23/08/2011].