Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Social Work

On-line version ISSN 2312-7198

Print version ISSN 0037-8054

Social work (Stellenbosch. Online) vol.50 n.1 Stellenbosch 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-13

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-1-13

Do social workers really make a difference? Measuring client satisfaction in an occupational setting

Arnel HuisamenI; Mike WeyersII

ILieutenant-Colonel (Dr) Arnel Huisamen, Police Social Work Services, SAPS, Mossel Bay, South Africa

IIProf Mike Weyers, Social Work Division, School for Psychosocial Sciences, North-West University: Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The past decade has seen a significant increase in the need amongst social workers to ascertain how clients experience their services (Tilbury, Osmond & Crawford, 2010:7779). This has been exemplified locally by a statement in the South African Department of Social Development's Integrated Service Delivery Model (2005:47) that touts the importance of client satisfaction surveys as a monitoring and evaluation instrument. Although this policy document dictates how government-supported local social work services should be delivered, very little has thus far been done to meet the need for client satisfaction surveys on a practical level. This is primarily because of the lack of appropriate, reliable and valid measuring instruments, as well as the logistical and ethical problems involved in the use of any such tools.

The Employee Health and Wellness (EHW) component of the South African Police Services (SAPS) experienced the same need and also faced the same challenges when its National Head gave instructions during August 2011 that a client satisfaction measuring instrument must be developed for this component. The responsibility for this task mainly fell on the shoulders of the authors and some collaborators.

The instruction gave rise to a study in which three client satisfaction scales were developed and pilot tested. Two of these scales, as well as the implications of their use for the broader social work field, are discussed in this article.

PRACTICAL AND THEORETICAL CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

The study should first be seen against the backdrop of the structure of employee-focused services in the SAPS. In the mid-2000s the then separate Police Social Work Services (PSWS), Police Psychological Services (PPS) and Police Spiritual Services (PSS) were grouped into one component, viz. Employee Health and Wellness (EHW). It was also decided that these three sections must follow an integrated approach. This step implied, among other things, that common ground should be sought between the services and that, whenever possible, similar procedures should be followed and tools used. This meant that representatives of the other professions also had to be consulted during the development of the client satisfaction scales in order to create similar or equivalent instruments for them at a later stage.

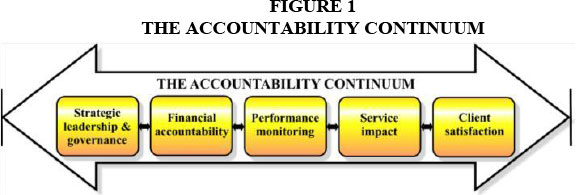

A second factor that should be taken into account is the accountability-related research that members of the EWH had previously completed. Within this context, accountability can be seen as a continuum that stretches from strategic leadership, on the one hand, to client satisfaction, on the other. This continuum is summarised in Figure 1.

Based on: Jamali, Safieddine and Rabbath (2008:445-447) and Swift (2001:16,19-20).

The completed research that has a bearing on some of the components of the accountability continuum (see Figure 1) includes:

- a study that led to the acceptance of the strengths-focused approach as the strategic service delivery paradigm for the Police Social Work section (Stutterheim & Weyers, 2004);

- a number of return-on-investment (ROI) studies that have a bearing on financial accountability and showed, among other things, that the organisation's investment in social work services is a "profitable endeavour" (Huisamen & Weyers, 2009:456457; Williams & Weyers, 2009:380);

- a study into the effectiveness of EHW's Service (delivery) Information Record (SIR) system that has a bearing on the monitoring of the performance of its practitioners (Janse van Rensburg, 2012); and

- a large number of studies that dealt with the impact or effect of social work services on personnel and new recruits (Weyers, Huisamen, Kleingeld & Williams, 2006).

The only component of the accountability continuum that has not yet received any direct attention is client satisfaction (see Figure 1). One reason is probably the many difficulties that are associated with this type of research. The six most pertinent difficulties are the following.

- Determining who the "client" really is. Is it, for example:

- the direct recipients of services;

- the legislative structure, courts or an organisations management system that demands that certain services should be rendered;

- the system that "pays" the social worker's salary; or

- the system/person that refers someone to the social worker?

- Obtaining informed consent from "clients". Difficulties include:

- children and adults with cognitive impairments who are not in a position to provide such consent;

- adults who are unwilling because of fear of being stigmatised or victimised; and

- organisations that might fear the effect that negative responses will have on their image.

- Deciding on the most appropriate timing of measurements. Client satisfaction levels can vary greatly over time, especially if measurements involve prolonged contact.

- Selecting an appropriate data-collecting instrument. These instruments can vary from:

- schedules for telephonic or personal interviews and the accompanying danger of "data contamination";

- to different types of self-administered questionnaires with their potentially low return rates and scope for the misinterpretation of questions.

- Meeting reliability and validity requirements. These requirements are notoriously difficult to meet in the case of self-assessments or self-reports because of, amongst other things:

- the overall subjective and emotive nature of this field;

- the inclination of some respondents not to be completely honest; and

- respondents' tendency to give highly fluctuating responses because of the "contrast effect" brought about by too high or too low original expectations.

- Meeting ethical requirements. These include:

- safeguarding the anonymity of respondents; and

- at the same time acquiring sufficient data to make somewhat detailed changes to services (Hsieh, 2012:529-533; Swift, 2001:18-19,23-24); Tilbury et al., 2010:83-86.

In order to overcome some of these difficulties, a strategic decision was taken at the outset not to limit the study to a single instrument. The nature of the services rendered by the EHW component through its social work section requires that two types of services and two stakeholders would have to be accommodated. The services are, on the one hand, those of a more therapeutic/individual-centred nature and, on the other, the EHW's various (group work-based) proactive personnel capacity-building programmes. The stakeholders are the recipients of these services and the managers who refer them to these services (known as "referral agents"). As a result, three instruments had to be developed. They ultimately became known as:

- the Individual Client Satisfaction Scale (ICSS);

- the Referral Agent Satisfaction Scale (RASS); and

- the Programme Satisfaction Scale (ProSS).

Because of length constraints and the fact that elements of the ProSS have already been covered in other publication (Weyers et al., 2006), only the first two scales are dealt with in this article.

THE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

The study utilised the design and development (D&D) research model and process (De Vos & Strydom, 2011:476-485) as a general guideline. In this case, the design of the scales went through the following five phases:

- A literature study;

- Compiling of draft ICSS and RASS scales/questionnaires;

- Peer review of these draft scales and revision and finalisation of the instruments;

- Pilot testing of the scales;

- Measurement of their reliability and validity.

In order to place the resulting scales into perspective, each phase is briefly discussed below.

Phase 1: The literature study

The draft questions and scales were based on the results of a comprehensive literature study. The analysis focused on, amongst other things, the requirements that a client satisfaction survey questionnaire and scale must meet, the constructs that can be covered by such instruments and the protocols that should be followed in their utilisation. Because of the rather unique occupational social work context in which the study was conducted, sources from a variety of other fields also had to be consulted. These varied from healthcare and nursing to psychology, and from human resources management to social work (Dauenhauer, Mayer & Mason, 2007:47-53; Grinnell, Gabor & Unrau, 2012:253-259; O'Brien & Stewart, 2009:109-117; Tilbury et al., 2010:81-87; Trotter, 2008:266-272; Van Nie, Hollands & Hamars, 2010:340-343). Sources also covered the nature of the SAPS and social work within this occupational setting, as well as previous research into the effect of social work services (Huisamen & Weyers, 2006; Janse van Rensburg, 2012; Stutterheim & Weyers, 2004; Weyers, Strydom, & Huisamen, 2008).

Phase 2: The development of draft scales/questionnaires

A clear design philosophy is required to overcome the difficulties inherent in client satisfaction research and surveys (Ahlfors, Lewander, Lindstrom, Malt, Lublin & Malm, 2001:73). It was consequently decided from the outset that the questionnaires had to be:

- self-administered (i.e. respondents had to be able to complete them independently);

- short (preferably no more than 15 questions in total);

- quick to complete (preferably not requiring more than 5 minutes);

- easy to understand (i.e. accessible to client systems with different levels of education and from different language groups);

- in English (the language understood by most of the potential respondents);

- able to yield statistical data that would be easy to capture and interpret (even by persons who do not have a background in statistics);

- able to provide a mechanism through which the experiences of client systems and referral agents could be compared (if only on a very basic level); and

- able to produce reliable and valid scales and subscales.

It was then necessary to decide on the core components of the questionnaires. These components should, according to McNeill, Nicholas, Szechy and Lach (1998:2-3), constitute the specific and definable service attributes which individually influence the extent to which clients are either satisfied or dissatisfied with the service they receive.

The literature study and analysis of SAPS needs indicated that the Individual Client Satisfaction Scale (ICSS) should consist of four core components. They are:

- the accessibility of the practitioner;

- the quality and relevance of his/her services;

- the degree of professionalism with which the case has been handled; and

- the "general impression" that is left by the encounter.

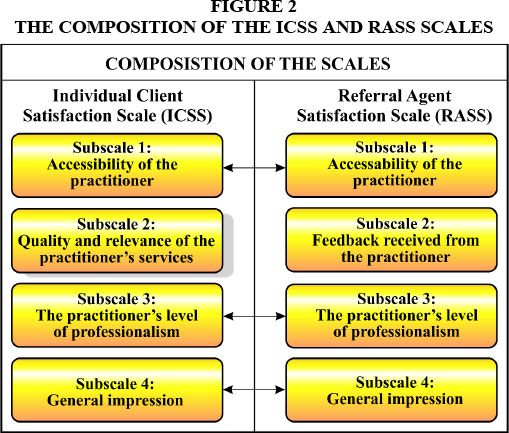

Each of the four components was converted into a subscale of the ICSS. The same principle was, with one exception, also applied to the Referral Agent Satisfaction Scale (RASS). Because of the nature of social work in an occupational setting, the "quality and relevance" subscale was replaced by a "feedback" subscale. An attempt was made to keep all the subscales as similar as possible in order to facilitate the drawing of comparisons.

The final composition of the scales and subscales is depicted in Figure 2.

The nature of the subscales contained in the two instruments, as well as the core constructs measured by each, will be covered briefly.

The accessibility of the practitioner (ICSS & RASS)

According to Barker (2003:3), the construct accessibility of service refers to "The relative opportunity for people in need to obtain relevant services". The subscale covers three types of accessibility (see Tables 3 & 4). They are the ease with which contact can be made with a practitioner (i.e. "reachability"), how soon after the first contact they become available for an appointment (i.e. "availability") and their availability after hours (an element of "convenience") (O'Brien & Stewart, 2009:113; Ribner & Knei-Paz, 2002:383-384).

The three types of accessibility also form part of the criteria used by the SAPS to rate the work performance of individual EHW practitioners. The results of the subscale could, consequently, also be used as a performance monitoring instrument (see Figure 1) in personnel management.

The quality and relevance of the practitioner's services (ICSS only)

The quality and relevance subscale is only contained in the ICSS. In essence, it deals with the technical competence of the practitioner and the extent to which his or her services meet expectations (McNeill et al., 1998:3-4; Wolniak & Skotnicka-Zasadzien, 2011:1239-1241). It consists of six questions. The first two questions focus on the practitioner's perceived level of expertise and the quality of his/her service. The others deal with the extent to which the service is on the client's level, whether it makes a difference in their lives and whose interest it serves best (see Table 3) (O'Brien & Stewart, 2009:113; Tilbury et al., 2010:80-81, 85-86).

The practitioner's level of professionalism (ICSS & RASS)

The second shared subscale (see Figure 2) deals with the extent to which the practitioner demonstrated professional behaviour or conduct (Barker, 2003:341). This includes traits such as punctuality, observing confidentiality, exhibiting empathy and treating the client/referral agent with respect. The literature study indicated that these traits form an integral part of effective service delivery (Jindani & Murdock, 2009:365-367; Kapp & Vela, 2004:278-279; Ribner & Knei-Paz, 2002:380, 382-384; Tilbury et al., 2010:85-87).

The general impression that is created (ICSS & RASS)

The next shared subscale covers what is termed the "general impression" left by the practitioner. It deals in essence with the perceived value of, or benefits derived from, the service (Tilbury et al., 2010:79-80). In the case of the ICSS, the individual client can, for example, evaluate if receiving the service is worth the effort (i.e. has a positive cost-benefit ratio) and if they will urge other personnel members to make use of it (i.e. worth a personal endorsement) (Hsieh, 2009:26-28; McNeill et al., 1998:3-4). The referral agents can, in the case of the RASS, indicate whether it has helped them to fulfil their role as manager.

The feedback received from the practitioner (RASS only)

Because of the nature of occupational social work, the study could not only focus on individual clients. It also had to accommodate the organisation's needs and best interest (Iversen, 1998:555-556) and, consequently, measure this "client's" satisfaction with services. In the study the organisation (i.e. SAPS) as client was represented by the referral agent.

The principle of confidentiality prevents practitioners from providing detailed information about individual clients and their progress to referral agents. It is, however, an organisational requirement that the managers who do these referrals must receive more generalised verbal or written feedback on the matter. The timeliness and quality of this feedback are covered by a separate subscale within the RASS (see Figure 2).

Phase 3: The peer-review of the concept scales and protocol

According to the design and development (D&D) process (De Vos & Strydom, 2011:480-484; Grinnell et al., 2012:36-37), it is prudent first to do a feasibility study and test draft scales/questionnaires before embarking on a pilot study. In this case, it was important to ascertain if the selected questions were concise and understandable, if clients and referral agents would answer them honestly, if the principle of confidentiality would be upheld, and if the intended protocol (i.e. distribution, completion and collection of questionnaires) would be feasible and appropriate.

It was also evident from the outset of the study that the proposed protocol and scales would, in the long run, have to serve a diversity of interests and provinces. This made it inappropriate to follow the 'usual' panel of experts or focus group verification route (Huisamen, 2005:61). The most appropriate alternative was to provide the draft instruments, together with evaluation questionnaires, to all the different EHW practitioners in three selected provinces for a peer review (Barker, 2003:320). The same provinces would then later also be used for the pilot testing of the scales/instruments.

Sampling

Because of logistical and time constraints, only three provinces could be used for the initial evaluation and subsequent pilot testing of the scales. The choice fell on Gauteng (a north-central province), the Western Cape (a western and coastal province) and Kwazulu-Natal (an eastern and coastal province). These three geographically dispersed provinces cover substantial numbers of the different population groups found in the Republic of South Africa. This criterion is important in order to ensure that people from a diversity of language groups will be able to understand the questions contained in the instruments. If taken as a whole, the triangle of selected provinces also provided a good mixture of urban, peri-urban and rural settings. This is especially important as far as the accessibility of practitioners is concerned.

Evaluation and recommendation by EHW practitioners

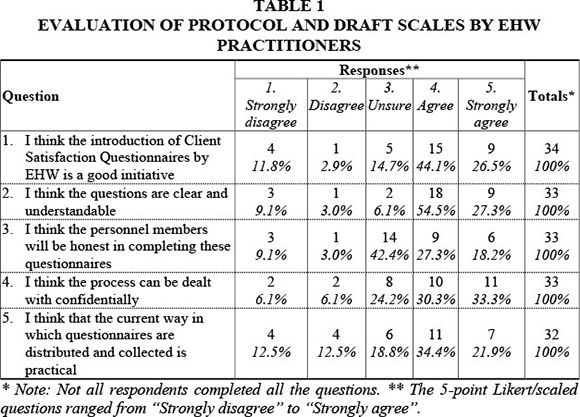

The protocol, scales and an accompanying evaluation questionnaire were sent to all the different EHW practitioners (i.e. social workers, psychologists and chaplains) in the three provinces. Their participation was completely voluntary and a total of 34 evaluation questionnaires were returned to the researchers. This response rate represents 15% of the targeted population.

The data produced by the questionnaire are contained in Table 1.

It was clear from the responses to the five Likert-type (scaled) questions, as well as the comments on the "recommendations" section of the evaluation questionnaire, that most of the respondents viewed the new initiative in a very positive light. Some concern was, however, expressed regarding the question of confidentiality and the protocol followed in the distribution and collection of the questionnaires. These would have to be rectified on an administrative level, when the project is implemented on a national level. Recommended changes to individual questions were incorporated in the scales that were readied for pilot testing.

Phase 4: The pilot testing of the instruments

The pilot testing of the ICSS and RASS in the three selected provinces took place from 18 September 2011 to 18 October 2011. As in the case of Phase 3, participation by clients, practitioners and referral agents was completely voluntary. In spite of the pitfalls associated with such a step, 136 ICSS questionnaires and 58 RASS questionnaires were returned to the researchers. This response rate was higher than expected and possibly indicative of a need amongst the participants to have the opportunity to air their views.

All the completed scales were submitted to the North-West University's Statistical Consultation Services for data capturing and analysis.

Phase 5: Determining reliability and validity

An important goal in the analysis was to determine whether the questions and scales were reliable and valid. Reliability entails the accuracy or precision of an instrument. It is also defined as the degree of consistency between two independently derived sets of scores/assessments, as well as how close the assessment is getting to what actually happened to the client (Roestenburg, 2011:26).

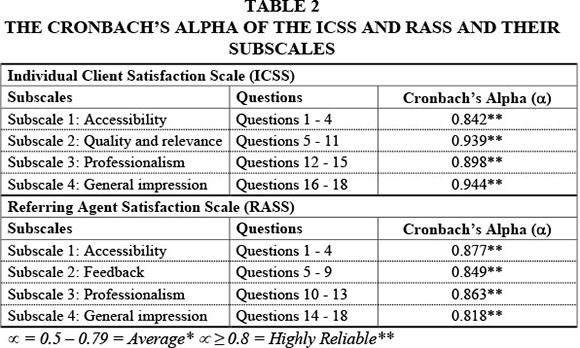

In order to determine their reliability, each scale's "Cronbach Alpha Coefficient" ("CA" or simply ("∝") had to be calculated (Gravetter & Forzano, 2003:455). A CA of α = 0.5 to 0.79 was viewed as acceptable and α≥ 0.8 as highly reliable (Gravetter & Forzano, 2003:455; Jackson, 2003:87-91). The CAs produced by the data analysis are contained in Table 2.

Table 2 indicates that both scales and their subscales are highly reliable (i.e. a = 0.8+), with two subscales even surpassing the 0.9 mark. This, therefore, implies that they could be used with confidence within the particular occupational setting.

The scales were also tested for construct validity, in addition to reliability. This basically implies the extent to which the instrument 'does what it is supposed to do' (Nestor & Schutt, 2012:121-122). The results indicated a high level of construct validity, especially in the way in which questions are clustered.

THE RESULTS OF THE PILOT STUDY

Although the research was mainly aimed at the development and verification of measuring instruments, their pilot testing has already produced results that could be of great value to both the EHW component of the SAPS and other organisations. These results and their implications are covered next.

Results produced by the Individual Client Satisfaction Scale (ICSS)

The data produced by the ICSS are contained in Table 3. This table is structured according to the four constituent subscales/components.

A number of trends emerged from the data produced by the ICSS (see Table 3). The most important of these are summarised below.

- An average of 74.8% respondents gave an overall positive rating (i.e. "agree" plus "strongly agree") to the accessibility of practitioners (Table 3: Subscale 1), with the highest positive average going to the ease with which appointments could be made with practitioners (Table 3: Q1). An unusual trend was the relatively large number of respondents (37/28.5%) who were "unsure" whether practitioners could be reached after hours and another 11 (8.5%) who were of the opinion that this was not the case (Table 3: Q3). This could be indicative either of a lack of knowledge or no attempt to do so. Because practitioners are on standby, this trend requires further investigation.

- Respondents gave the quality and relevance of practitioners' services (Table 3: Subscale 2) a very high overall positive rating of 86.9%. The two strongest elements were the quality of the services (Table 3: Q5, X = 89.5%) and the view that the services were in the client's best interest (Table 3: Q7, X = 88.7%).

- Subscale 3: The practitioner's level of professionalism produced the second highest overall positive rating of 89.1% (see Table 3). Respondents indicated that practitioners were compassionate (Table 3: Q12, X = 91.6%) and polite (Table 3:Q11, X = 91.6%), as well as trustworthy (Table 3: Q13, X = 88.5%). The only trait that measured slightly lower was punctuality (Table 3: Q10, X = 84.7%).

- The General impression subscale produced the highest overall positive rating (Table 3: Subscale 4, X = 89.8%), as well as the highest individual positive response (Table 3: Q14, X = 93.1%). These results should be viewed as significant, because the subscale basically deals with the perceived value of, or benefits derived from, the service (Tilbury et al., 2010:79-80). Especially the respondents' willingness to personally endorse the service (Table 3: Q14) bodes well for the extension of social work services to a larger proportion of the organisation's personnel.

- Three of the four subscales produced an overall positive rating in the 80%+ range. The only exception was Subscale 1 and in particular question 3 (see Table 3).

Results produced by the Referring Agent Satisfaction Scale (RASS)

A summary of the data produced by the pilot testing of the Referring Agent Satisfaction Scale (RASS) is provided in Table 4. This table is structured according to the scale's four constituent subscales.

The data produced by the RASS (see Table 4) brought a number of important trends to the fore. They include the following:

- The total positive rating (i.e. "agree" plus "strongly agree") per subscale all exceeded the 90% mark and was even 99.1% for the assessments of practitioners' level of professionalism (Table 4: Subscale 3).

- The lowest overall rating was for the accessibility of practitioners (Table 4: Subscale 1, X = 94.4%) and availability after hours again produced as relatively low positive response (Table 4: Q3, X = 85.0%). The other elements were, however, very positive and even reached the 100% mark for the ease with which appointments could be made with practitioners (Table 4: Q1).

- Although the overall positive rating in Subscale 2: Feedback received from the practitioner fell in the 90%+ range (Table 4: Subscale 2), an interesting trend emerged from the analysis of responses to individual questions. It was that, although verbal and written feedback were provided "within good time" (i.e. expeditiously), the quality of these responses was not on the same level (compare Table 4: Q5 & Q7 with Q4 & Q6). These are issues that would probably have to be taken up by the management cadre of the EHW services.

- The second highest positive result was produced by the General impression subscale (Table 4: Subscale 4, X = 98.2%). This willingness to again make use of the EHW practitioners' services (Table 4: Q12, X = 100%) and encourage other members to use it (Table 4: Q13, X = 100%), could be viewed as indicative of a large measure of trust that managers place in the social workers.

Results produced by the testing of the implementation protocol

The research did not only test the measurement scales, but also the protocol used in their distribution, completion, collection and interpretation. The results would ultimately indicate whether it would be feasible to expand their use to the total organisation.

The testing of the protocol in three provinces showed that it was fundamentally sound and could, with some minor changes, be replicated throughout the organisation and country. These required changes have a bearing on four practical, logistical and ethical difficulties.

It was, firstly, clear that an alternative method for the distribution and return of questionnaires will have to be considered. As opposed to the current process of using sealed 'drop-boxes' for the return of questionnaires, prospective respondents could be provided with pre-addressed envelopes. They could then mail them at the station/unit's registration office and from there they would be forwarded to EHW National Office in Pretoria. This should result in a higher level of confidentiality and also ensure that all the questionnaires would be mailed to a central point where the results could be calculated.

Secondly, one of the biggest concerns in the measurement of client satisfaction, especially in a clinical setting, is the threat to the anonymity of respondents. This concern was also shared by the EHW practitioners who participated in the peer-review process (see Table 1). The use of pre-addressed envelopes would, however, go a long way towards safeguarding each respondent's identity.

There was, thirdly, a general concern about the contamination of results. This would especially be the case in the completion of the ICSS, where the response rate will depend on the EHW practitioner's ability and willingness to convince his or her clients to complete and mail their questionnaire. The danger is that only those clients that adopt a "positive stance" towards the practitioner would be motivated to do so. There is no direct remedy to this danger. It would, however, be possible to identify an unusually low response rate by comparing a practitioner's service delivery statistics with the number of questionnaires received. It is also envisaged that, as the idea of client satisfaction is marketed throughout the organisation, clients would come to expect to have the opportunity to evaluate services and would "demand" to do so.

It was possible during the study to make use of advanced statistical consultation services and sophisticated computer programs in the capturing and interpretation of data. It would not be possible to replicate this within the SAPS on a continuing basis. Fortunately, both scales and their subscales had a very high Cronbach Alpha Coefficient (see Table 2) and this, coupled with their construct validity, implies that they could be viewed as standardised instruments for use within the organisation. It will consequently not be necessary to test all new batches of questionnaires/scales for reliability and validity. The data that they produce can be used with confidence in the interpretations of the levels of the clients' satisfaction. This can even be achieved through the use of descriptive statistics.

The proposed protocol is that completed questionnaires would be forwarded from each station's/unit's registration offices to the EHW National Office where the data would be captured on an available computer program such as Epidata or MSExcel. In the interpretation of the resultant descriptive statistics, note should be taken of the fact that the selected 5-point Likert-type scale does not have a "0". An average "mark" of between 3.41 and 4.2 (68.2% and 84%) would consequently indicate an "above average" or "good" positive response, and between 4.21 and 5 (84.2% & 100%) an "excellent" rating. It is also proposed that the results would be communicated to the different provinces on a regular (e.g. monthly) basis.

FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

Only the main results produced by the study, as well as their implications, are covered next.

The literature study first of all clearly indicated that the field of client satisfaction research and practice should not be taken lightly. It forms a vital part of the responsibility to remain accountable that practitioners have towards both their employers and clients and, in essence, answers the question: "Do the social workers really make a difference?" To produce clear and substantiated answers requires scientifically tested and verified measuring instruments based on in-depth research. The procedure used in this study can be used as a guideline in such an endeavour.

A second finding was that it is possible to develop and standardise, as well as successfully utilise, client satisfaction scales within South African social work practice. This paves the way for the development of specific scales for different social work settings. The latter can range from occupational social work to generic practice, and from statutory social work to different types of specialised services.

The ICSS and RASS, thirdly, proved to be highly reliable and valid measuring instruments. This result has the following three core implications:

- The first is that the EHW component of the SAPS can proceed with the implementation of the scales/instruments on a national level, as well as extend their use to psychologists and chaplains;

- Secondly, because of the reliability and validity levels attained, it should be possible to utilise the scales in other occupational social work settings. This will only require minor changes to some of the wording used;

- A third implication is that the scales/instruments can be used as a template in the development of similar instruments for other settings. Especially the ICSS can be used in generic practice, with a few additions and changes to mainly the "Accessibility of practitioner" subscale.

The study, fourthly, did provide an answer to the question: "Do the social workers really make a difference?" The very high level of satisfaction with their services in the selected three provinces proves that this is indeed the case. The results, however, also pinpoint two possible areas for further improvement. They are the availability of practitioners after hours and the quality of the feedback provided to referral agents.

It is not expected that the statistically high levels of satisfaction attained with the pilot will be maintained when the measurement process is rolled out to the entire organisation. In order to accommodate a possible Hawthorne effect produced by the knowledge of respondents that they were participating in a study (Grinnell et al., 2012:220), a lower benchmark should be selected. The study indicated that a statistical average "mark" per question/scale of between 3.41 and 4.2 (68.2% and 84%) should be considered as "good" and between 4.21 and 5 (84.2% and 100%) as "excellent".

The final finding pertains to the protocol followed in the utilisation of the client satisfaction questionnaires/scales. The literature abounds with examples of practitioners and organisations using practical, logistical and ethical considerations as a justification for not utilising client satisfaction instruments in their particular settings. The current study indicated that, even though it poses difficulties, such stumbling blocks can be overcome.

If the measurement of client satisfaction were to become as widespread as the Department of Social Development's Integrated Service Delivery Model (2005:47) envisaged, all relevant parties would be the beneficiaries. This will include clients who will have a greater say in the quality and relevance of the services that they receive as well as the social workers who will be able to prove that their services really make a difference.

REFERENCES

AHLFORS, U.G., LEWANDER, T., LINDSTROM, E., MALT, U.F., LUBLIN, H. & MALM, U. 2001. Assessment of patient satisfaction with psychiatric care. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55(44):71-90. [ Links ]

BARKER, R.L. 2003. The social work dictionary. Washington: NASW Press. [ Links ]

DAUENHAUER, J.A., MAYER, K.C. & MASON, A. 2007. Evaluation of adult protection services: perspective of community professionals. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 19(3-4):41-57. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. 2005. Integrated service delivery model: towards improved social services. Pretoria: Department of Social Development. [ Links ]

DE VOS, A.S. & STRYDOM, H. 2011. Intervention research. In: DE VOS, A.S., STRYDOM, H., FOUCHI, C.B. & DELPORT, C.S.L. (eds) Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions (4th ed). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 473-490. [ Links ]

GRAVETTER, F.J. & FORZANO, L.B. 2003. Research methods for the behavioral sciences. Belmont: Thomson/Wadsworth. [ Links ]

GRINNELL, R.M., GABOR, P.A. & UNRAU, Y.A. 2012. Program evaluation for social workers: foundations of evidence-based programs (6th ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HSIEH, C-M. 2009. Importance counts: The role of relative importance of service elements in client satisfaction measures. Journal of Social Service Research, 35(1):23-31. [ Links ]

HSIEH, C-M. 2012. Perceived importance of service elements in client satisfaction measures. Journal of Social Service Research, 38(4):529-540. [ Links ]

HUISAMEN, P. 2005. Die effek van die besluitnemings- en lewensdoelkomponente van die SAPD se Selfbestuur Personeelkapasiteitsbouprogram. (The effect of the decision-making and purpose-in-life components of the SAPS Self-Management personnel capacity-building programme). Potchefstroom: North-West University. (PhD thesis) [ Links ]

HUISAMEN, P. & WEYERS, M.L. 2006. Die meting van program-effek: Riglyne vanuit geselekteerde subprojekte van die EPCaP-studie (Measuring programme effect: Guidelines from selected subprojects of the EPCaP study). Social Work Researcher-Practitioner/Maatskaplikewerk-Navorser-Praktisyn 18(3):224-265. [ Links ]

HUISAMEN, P. & WEYERS, M.L. 2009. Teaching employees money management skills and showing a profit in the process: lessons from a financial literacy course. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 45(4):443-460. [ Links ]

IVERSEN, R.R. 1998. Occupational social work for the 21st Century. Social Work (NASW), 43(6):551-566. [ Links ]

JACKSON, S.L. 2003. Research methods and statistics: a critical thinking approach. Belmont: Thomson/Wadsworth. [ Links ]

JAMALI, D., SAFIEDDINE, A.M. & RABBATH, M. 2008. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: synergies and interrelationships. Corporate Governance: an International Review, 16(5):443-459. [ Links ]

JANSE VAN RENSBURG, M.M. 2012. The capturing, provision and interpretation of service delivery information by police social workers: obstacles and solutions. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (MSW dissertation) [ Links ]

JINDANI, S.G. & MURDOCK, V. 2009. Toward client-centered service: asking clients for their views of TANF, food stamps, child care, and Medicaid services. Journal of Social Service Research, 35:364-379. [ Links ]

KAPP, S.A. & VELA, R.H. 2004. The Parent Satisfaction with Foster Care Services Scale. Child Welfare, LXIII(3):263-287. [ Links ]

McNEILL, T., NICHOLAS, D., SZECHY, K. & LACH, L. 1998. Perceived outcome of social work intervention: beyond consumer satisfaction. Social Work in Health Care, 26(3):1-18. [ Links ]

NESTOR, P.G. & SCHUTT, R.K. 2012. Research methods in psychology: investigating human behaviour. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

O'BRIEN, M.W. & STEWART, S.J. 2009. Measuring satisfaction with social work services. Social Work in Health Care, 48(2): 105-118. [ Links ]

RIBNER, D.S. & KNEI-PAZ, C. 2002. Client's view of a successful helping relationship. Social Work (NASW), 47(4):379-387. [ Links ]

ROESTENBURG, J.H. 2011. Ecometrics in social work. Johannesburg: Afri.Yze Publishing. [ Links ]

STUTTERHEIM, E. & WEYERS, M.L. 2004. Strengths-focused intervention: the new approach of the Social Work Service of the South African Police Service (SAPS). Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 40(1):1-14. [ Links ]

SWIFT, T. 2001. Trust, reputation and corporate accountability to stakeholders. Business Ethics: A European Review, 10(1):16-26. [ Links ]

TILBURY, C., OSMOND, J. & CRAWFORD, M. 2010. Measuring client satisfaction with Child Welfare Services. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 4:77-90. [ Links ]

TROTTER, C. 2008. What does client satisfaction tell us about effectiveness? Child Abuse Review, 17:262-274. [ Links ]

VAN NIE, N.C., HOLLANDS, L.J.M. & HAMARS, J.P.H. 2010. Reporting quality of nursing home care by an internet report card. Patient Education and Counseling, 78:337-343. [ Links ]

WEYERS, M.L., HUISAMEN, A., KLEINGELD, C. & WILLIAMS, M. 2006. Personnel Capacity-Building Programs: an effective addition to curative services in occupational social work settings? Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health (previously EAP Quarterly), 22(1):65-87. [ Links ]

WEYERS, M.L., STRYDOM, H. & HUISAMEN, P. 2008. Triangulation in social work research: the theory and examples of its practical application. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 44(2):207-222. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, H.M. & WEYERS, M.L. 2009. Combating workplace conflict through education: The content and effect of a conflict management and assertiveness training programme. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 45(4):367-384, October. [ Links ]

WOLNIAK, R. & SKOTNICKA-ZASADZIEN, B. 2011. The concept study of Servqual method's gap. Quality & Quantity, 46:1239-1247. [ Links ]