Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Historia

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8392

versão impressa ISSN 0018-229X

Historia vol.68 no.2 Durban Nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2023/v68n2a4

ARTICLES

The Development of Christian Care Aid in Zimbabwe: The Case of Matabeleland Region, 1967-c.1990

Tinashe Takuva*

Lecturer in Environmental History at the University of Edinburgh

ABSTRACT

The organisation, Christian Care, was formed during Zimbabwe's liberation war in 1967 to disburse emergency aid to victims of the war and political repression. From 1967 to about 1990, it provided emergency relief and charity aid to victims of war and the marginalised people in Zimbabwe. This article explores the development of Christian Care aid from its inception to around 1990, tracing the changes over time. It shows how Christian Care managed to respond to the situation on the ground even when such an agenda was not in line with what the government of the day practised. Between 1967 and 1980, Christian Care's aid was largely emergency based, assisting war victims with food, clothes and money. After 1980, the nature and composition of aid changed to development projects such as drilling of boreholes, construction of schools, clinics and dams and assisting communities to set up income generating projects like market gardens. Using a qualitative research methodology with predominantly archival sources, I explore the development of Christian Care aid in the Matabeleland region of Zimbabwe, demonstrating how the organisation provided assistance to the repressed and marginalised.

Keywords: Christian Care; Zimbabwe; Matabeleland; emergency aid; governance; community development.

OPSOMMING

Die organisasie, Christian Care, is in 1967, tydens Zimbabwe se vryheidsoorlog, gestig om noodverligting aan slagoffers van die oorlog en politieke onderdrukking te bied. Vanaf 1967 tot ongeveer 1990 het dit noodverligting en liefdadige hulp aan oorlogslagoffers en gemarginaliseerde mense in Zimbabwe gebied. Hierdie artikel ondersoek die ontwikkeling van Christian Care vanaf sy stigting in 1967 tot ongeveer 1990, en wys daardeur op die verandering oor tyd. Dit wys ook hoe Christian Care daarin geslaag het om te reageer op voetsoolvlak omstandighede, selfs toe sy agenda nie ooreengestem het met dié van die regering van die dag nie. Tussen 1967 en 1980 was Christian Care se hulpverlening meestal op krisisse toegespits, en het die organisasie oorlogslagoffers bygestaan met kos, klere en geld. Na 1980 het die aard en inhoud van die hulpverlening verander na ontwikkelingsprojekte, soos die sink van boorgate, die bou van skole, klinieke en damme, en bystand aan gemeenskappe om inkomste-genererende projekte, soos mark tuine, van die grond af te kry. Deur gebruik te maak van 'n kwalitatiewe navorsingsmetodologie met oorwegend argivale bronne, stel ek ondersoek in na die ontwikkeling van Christian Care se hulpverlening in die Matabeleland-streek van Zimbabwe, en wys daardeur hoe die organisasie hulp verleen het aan die verdruktes en verwaarloosdes.

Keywords: Christian Care; Zimbabwe; Matabeleland; noodverlening; regeerkunde; gemeenskapsontwikkeling.

Introduction

This article explores the development of Christian Care aid in Zimbabwe from the formation of the organisation in 1967 to about 1990. It pays particular attention to the nature and composition of Christian Care aid and how its pursuits and objectives changed over time. The article defines and places Christian Care aid within the existing knowledge of systematic, emergency and charity-based aid by examining the nature and structure of the aid which it disbursed. More than this, I analyse the forms which the aid took and conclude whether it was just not emergency/charity aid, but also qualifies to be categorised as development aid.1

Christian Care, I argue, provided assistance to victims of political repression and marginalisation in the context of the liberation war and post-war Gukurahundi2massacres as well as victims of natural disasters like drought in the Matabeleland region. Beyond that, where possible, it partnered government in post-war economic reconstruction by implementing the national economic blueprint in areas it operated in, especially after 1986. The article uses archival information in the form of organisational reports and correspondence as well as newspaper articles.3

Christian Care was formed in 1967 by the Christian Council of Rhodesia (CCR), which had been established in 1964, as a result of intensified political arrests by the Rhodesian Front government. When nationalists such as George Nyandoro, James Chikerema, Edson Sithole and Joshua Nkomo started mobilising the black majority in Southern Rhodesia to fight for independence between 1955 and 1963, the government responded by enacting draconian laws such as the Law-and-Order Maintenance Act of 1960 (LOMA) and banning political formations to curb the African nationalist agitation.4 This led to the arrest and detainment of many black people for political reasons. The situation worsened after the Ian Smith government declared a state of emergency in 1965 and the guerrilla war5 gained momentum soon after. In response, the CCR gave open support to the political prisoners and their dependents and asked for financial assistance from the World Council of Churches. When Christian Care started assisting political prisoners, the organisation had a budget of a mere £80.6 Thereafter the budget of the diversified relief programme for the prisoners and their families increased dramatically to £25 000 in 1967, £35 000 in 1968 and approximately £50 000 in 1969.7 However, the open support for prisoners and their dependants by the CCR was short-lived because in 1966 the Smith administration blocked the organisation from carrying out their welfare programme by passing the Welfare Act.8 This act disqualified the CCR, a non-welfare institution, from carrying out welfare duties. This step reflects the antagonistic church/state relations during the liberation struggle in which the state was against the church's support for war victims. In response, the CCR founded Christian Care and registered it as a charity organisation loosely attached to the CCR. As a charity organisation, Christian Care became closely involved in both charity and developmental issues. It was funded by different organisations like the International Aid Fund, the Red Cross, and several other churches. The CCR became known as the Zimbabwe Christian Council after independence in 1980. Due to the circumstances surrounding its formation, the organisation focused largely on emergency or relief aid until about 1980. This was to change after 1980 when Christian Care began to complement the government's reconstruction efforts by channelling developmental aid rather more than charity/emergency assistance and began implementing economic projects in marginalised areas.

At its formation, Christian Care set up three committees to carry out its duties, namely, the Projects Committee, the Emergency/relief Committee and the Education Committee.9 Inasmuch as Christian Care often categorised aid for education as a form of relief aid, it should be noted that educational aid was a key aspect of developmental aid disbursed during the colonial period. Education assistance was often in the form of the payment of school fees for the detainees to study whilst in prison, or for the education of their children outside prison. It also assisted those who could not afford fees as a result of economic hardships and whose families were categorised as destitute. The Bulawayo Relief Committee admitted that this assistance was not strictly emergency relief or educational aid, and for that reason beneficiaries were directed to obtain remission forms from the headquarters of the organisation in Harare. These forms had to be sanctioned by a Social Welfare Officer that the people concerned were indeed 'destitute'.10 School fees were provided for the recipients to enrol in a number of different institutions and for various courses which helped to boost human capital, a key development tool. This example of aid for educational purposes shows how debatable it is to characterise aid as either 'charity' or being 'developmental'.

Contextualising Christian Care aid: Church-state relations, the liberation war and Gukurahundi in Zimbabwe, 1950s to 1980s

Aid has become a contentious subject among academics, policy makers and politicians. In academic circles, it has aroused the 'great aid debate', on aid effectiveness since 2000. In this debate, dominated by economists, scholars agree that aid does not work, or does not fulfil its intended mandate, but they differ on what should be done. While one group is of the view that aid must be cut since it is ineffective,11 the other group thinks aid can be changed or altered to ensure effectiveness.12

In this debate, the focus is on systematic aid rather than any other form of assistance. Dambisa Moyo classifies the types of aid into three broad categories, namely humanitarian or emergency aid, charity and systematic aid. She defines humanitarian aid as being disbursed in response to catastrophes, while charity aid is disbursed by charity organisations to people on the ground and systematic aid is assistance in the form of loans and grants transferred from one government to another (bilateral) or between an institution like the World Bank and a government (multilateral).13 Moyo declares that her book is not concerned about emergency and charity aid because 'the significant sums of this type of aid that flow to Africa simply disguise the fundamental (yet erroneous) mindset that pervades the West - that aid, whatever its form, is a good thing.'14

In her justification for this opinion, Moyo ignores the growing influence of the non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector in recent years which has seen such funding increase and the visibility of the sector expand substantially in policy making and in the media.15 Christian Care aid (emergency and charity), therefore, is insignificant to Moyo's 'dead aid' thesis because they are 'small beer'16 compared to systematic aid. For her, it is systematic aid that has 'hampered, stifled and retarded Africa's development'.17 The only criticism she lays against charity aid is that at times it is characterised by poor implementation, high administrative costs and bidding for donors' governments as opposed to the needs on the ground.18 As shall be shown in this article by tracing the development of Christian Care aid in the Matabeleland region, the charity organisation generally passed this litmus test. This, therefore, is a micro-study of aid, concerned about the 'small beer', exploring how Christian Care aid developed over time shifting from one that was exclusively an emergency response to the war and conflict, to a more developmental approach. I argue that between 1967 and 1990, Christian Care assisted the needy who were either victims of state repression and marginalisation or the victims of natural disasters, primarily the effects of prolonged drought. Essentially, Christian Care aid developed to deal with emergencies that arose when the state either had wrong priorities or inadequate capacity. The study situates the development of Christian Care aid within the broader histories of the war of liberation, the subsequent massacres known as Gukurahundi and church-state relations during the entire period.

Church-state relations in Zimbabwe during the period under study were characterised by the state's increasing repression over indigenous Africans and the church's criticism of the state. Scholarship on church-state relations in post-1945 colonial Zimbabwe demonstrates how such relations were good before 1972 but turned sour thereafter. Ian Linden observes that by the 1960s the Catholic church did not support African nationalists, and that the relationship between church and nationalists deteriorated and 'came to be seen as mutually incompatible'.19 The reason for this hostile relationship is twofold. First, the church viewed nationalism as being communist inspired, suggesting that it was no more than communism in different terminology20 and had been aligned to the state from the very onset of colonisation itself, having paved the way for colonisation in what certain scholars typified as 'the flag following the cross.'21 Although the church spoke up against repressive laws by the state, it did not take an official, pro-nationalist and anti-state position. Linden opines that the Catholic Church did not support African nationalism at the critical juncture between 1958 and 1963 because of its 'belief that nationalism was not the answer to the problems of social justice in Rhodesia' and that 'Zimbabwean nationalism viewed from the mission station seemed an amorphous, vague and essentially uncoordinated set of phenomena graced with too much unity by the description "movement"'.22 He concludes:

... the major course of the teaching church's failure to come to terms with African nationalism at this point seems to have been the blinkered perspective caused by ideological involvement with imperialism and, practically, the vestigial development of a listening church responsive to African nationalism."23

The second strand of the church-nationalist relationship which shaped church-state relations, was the perception of the church by nationalists. During this period, African nationalists were largely hostile to the church and Christianity, rightly accusing the church of being pro-state. Trade unionists, the majority of whom were part of the nationalist movement, followed the same script, accusing the church of making people too soft and docile towards the government.24 During this period, therefore, church-state relations were fraught.

The church-state relations turned increasingly sour, with the church speaking out against the state and supporting the nationalist movement, culminating in the formation of Christian Care in 1967. A change bega n in the early 1960s when the church opposed the Community Development approach25 taken by the government because it 'threatened to curtail church control in rural areas, particularly over schools.'26 This was followed by an immediate and more open support for the nationalists and by the early 1970s the missionaries were being labelled as subversive by the state. When guerrilla attacks occurred on farms in Centenary (Mashonaland Central) in December 1972, farmers called for the closure of St Albert's mission in the area accusing the missionaries stationed there for being involved in the attack.27 The Minister of Internal Affairs, Lance Smith, buttressed this call by suggesting in parliament that 'Some missionaries aided and abetted terrorists and it was held that the St Albert's Jesuits, some of whom had even been imprisoned in Communist East Germany, were Marxist collaborators of the local ZANU forces.'28

The major turning point in this relationship, however, was the creation of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) in 1972. Janice McLaughlin attributes the sudden change in church-state relations to the setting up of the commission which amplified the voice of the church. According to McLaughlin, the commission exposed and criticised the government's handling of the war, much to the infuriation of government officials.29 The commission had to play an almost similar role during the post-independence Gukurahundi massacres when it drew 'world attention to the conflict in western Zimbabwe... [and forced] the government to investigate its military operations'30

Outside the more pronounced Catholic church's position, other churches such as the regional based, Brethren in Christ Church (BICC) were largely mute in political affairs but their members often had to take a side. Wendy Urban-Mead, in her study of the church, family and gender in Matabeleland during colonial rule, observes that at doctrinal level, the BICC encouraged its members to 'refrain from involvement in party politics and shun involvement in world governments.'31 However, this proved difficult for the African membership of the church in the context of an anticolonial nationalism. As a result, the majority of the African membership of the church in the region supported the guerrillas because they identified with the grievances outlined by the nationalists. The same transpired during Gukurahundi, when the church maintained its apolitical position but members fell victim to violence. Being a Matabeleland (both North and South as well as the capital, Bulawayo) based church, members found themselves at the centre of violence, with some of the members being directly targeted because they were also members of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). In Gwai District, Matabeleland North for instance, Urban-Mead notes that all 'of the male BICC pastors who were also ZAPU officers were killed...'.32 Yet the church did not comment on these atrocities even in its official publications like the Good Words/Amazwi Amahle which instead dedicated space to 'celebrating, promoting and goading church growth and evangelism as well as spiritual development for youth and new members.'33 A considerable shift occurred with the involvement of the church's bishop, Steven Ndlovu, who participated in a faith-based delegation which engaged government to stop Gukurahundi in 1987.34

As is now clear, the development of Christian Care aid and the changing church-state relations took place in an environment of war, repression and violence. The two major events shaping this environment, the liberation war and Gukurahundi atrocities occupy considerable space in Zimbabwean historiography. Two major themes that can be drawn from the liberation war literature are the guerrilla and society experiences. Ngwabi Bhebe and Terence Ranger's edited volume comprises essays on soldiers' experiences in the war and discusses strategies adopted by the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) and Zimbabwe African National Liberation (ZANLA),35 while a comparison is also made of the guerrilla intelligence services employed by the Rhodesian government.36 A more detailed account on the experiences of the combatants, although limited to imprisonment, is provided by Munyaradzi Munochiveyi. He argues that the political activities of ordinary people was 'at the centre of the growth of mass-based nationalism and liberation movements in Zimbabwe',37 hence many of them were imprisoned. His work reconstructs the life of detainees in detention centres by conducting interviews and writing oral histories. He notes that detention centres were meant to cut off political activists from communities, thereby weakening African political opposition.38 However, the detainees challenged this objective by 'reorganising the detention spaces and taking control of them ... instead of conforming to the dreary and disempowering monotony of detention life, they took advantage of their captivity to empower themselves through academic and political education and political debate...'39 Building on this detailed account of detainees' living conditions and their adaptive methods in detention (and that of their families outside), this study explores the role of Christian Care aid in assisting the detainees and their families.

The second theme outlined above, that of society's experiences, has also been explored. Focusing on Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU)'s mobilisation efforts during the war, Norma Kriger articulates the motives behind peasants' participation. She suggests that whereas the guerrillas coerced peasants into participation, sometimes by destroying infrastructure like rural schools, clinics and dip tanks to deny peasants the few benefits they had, peasants exploited the opportunities provided by participation in the war to better their societies.40 As they gained a voice through their position in the network of organising support for guerrillas, some used such authority to challenge abusive chiefs and elders in the communities; others to better their livelihoods through access to resources, and there were also some women who challenged domestic violence.41 While Bhebe and Ranger's 1995 volume focuses on soldiers' experiences, their 1996 volume also includes contributions on societal experiences. These explore how religion, ideology and education were central to the connection between guerrillas and society at large.42 There are however some historiographic silences in the liberation war histories. In particular there is a dearth of literature on the urban population's experiences and the scant literature on wartime experiences in Matabeleland North.43 Although this article does not provide an account of war experiences in Matabeleland North, it contributes to the scant literature by demonstrating the presence of Christian Care aid in the area during and after the war.

In a broad survey of Zimbabwe's socio-political landscape 'from liberation to authoritarianism', Sara Dorman summarises the diverse nationalist movement of the 1950s to 1980, unpacking the heterogeneous groups, inter-party and intra-party differences and similarities in the nationalist movement. She also looks at the competition which ensued to gain the support and legitimacy of the masses44 and engages in the academic conversations on guerrilla-peasant relations, noting that 'the relationship was not always straightforward or easy'.45 The peasants' attitude towards guerrillas, she explains, was shaped by their experiences of violence and hardship at the time. Dorman also articulates the heterogeneity of white settlers, observing that some were pro-Smith (the then prime minister of Rhodesia), some anti-Smith and some who eschewed politics and were more concerned about business interests.46 She then highlights the role of organisations during the war, and notes the difference between the Catholic Church through the CCJP which was closely and radically involved in the war and the Protestant churches whose position was ambiguous.47 Although she does not provide a detailed account of Christian Care works, Dorman captures its role aptly, saying that it 'became an important support for families of detained nationalists.'48

Beyond the national perspective, some scholars have reconstructed Zimbabwe's wartime experiences focusing on particular regions. Writing on the culture and history of the Matopos in Matabeleland southern province, Ranger reveals how the natural landscape of Matopos provided the ideal place for guerrilla tactics in the 1970s, and later provided cover for the so-called dissidents during Gukurahundi in the 1980s.49 Similarly, drawing largely from oral interviews, the authors explore Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA)'s war strategy in Matabeleland, in particular the takeover of control of Shangani from the Rhodesian government.50 These broad histories of the war provide an analytical framework for the development of Christian Aid in Zimbabwe.

In the post-1980 period, the development of Christian Care aid in Matabeleland region was largely shaped by state action, in particular the Gukurahundi atrocities and post-war economic reconstruction rhetoric. Thembani Dube identifies three literature strands on Gukurahundi. The first, a pro-ZANU strand, blames ZAPU for attempting to claim victory after losing the 1980 elections, resulting in the ZANU government using brutal force to suppress a possible uprising. The second, a pro-ZAPU strand, views the atrocities as an attempt by ZANU to ride on the incidents of violence after 1980 in order to wipe away ZAPU and thereby to dominate the region. A third strand blames Gukurahundi on apartheid South Africa's regional destabilisation agenda.51 While this broad literature focuses on aetiology, emerging scholarship on the subject is shifting attention to memorialisation.52 This approach allows a reconstruction of Gukurahundi atrocities based on oral histories, thereby providing a victims-centred analysis. Following these histories of Gukurahundi, this study demonstrates how Christian Care aid became critical at the time. Understanding the development of Christian Care aid in Matabeleland between 1967 and 1990, requires an appreciation of the violent, repressive and marginalisation environment of the time.

'Response good but more clothes, please!' Christian Care's emergency relief aid, 1967-1979

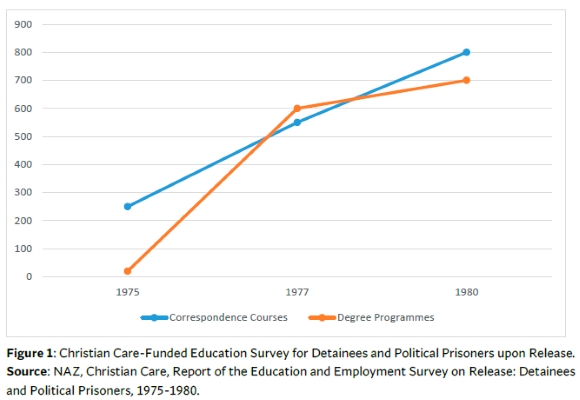

From the time of its formation until Zimbabwe's independence, Christian Care aid across Zimbabwe concentrated on emergency relief with particular focus on assisting political prisoners and their dependents who were imprisoned as a result of the liberation war. Relief aid included payment of school fees for both prisoners and their dependents, and also paying for accommodation, train and bus fares for those visiting their detained or imprisoned relatives. It also included food handouts.53 In addition, Christian Care facilitated external educational correspondence courses for many political detainees who had been arrested, particularly those with lower educational qualifications such as primary school certificates. This aid meant that many recipients emerged as graduates at external universities at the end of the war. Some beneficiaries of educational aid include Dickson Mlambo, who was arrested on 11 April 1968 and released on 2 April 1980 and Nelson Mlalazi, arrested on 17 December 1976 and released in July 1979. Richard Mlalazi was imprisoned on 14 May 1977 and released on 21 November 1979, while Mloyiswa Mlalazi was imprisoned in October 1977 and released in April 1980. These men were among many who received aid.54 Correspondence courses included tuition in primary education, Rhodesian Junior Certificate at Ordinary Level and Advanced Level and also certificates in Bookkeeping, Salesmanship, Sales Management, the Diploma in Management, Diploma in Mixed Farming, and the Diploma in Accounting.55 University degree programmes included those for a Bachelor of Administration, Bachelor of Arts (General) and Bachelor of Arts in Geography. Degrees in Law and Engineering were also offered.56 Some of the universities and colleges involved in these programmes were the University of Dar es Salaam, the University of Rhodesia, the University of South Africa, the University of London, the Central African Correspondence College, the Rapid Results College, the Institute of Administration and Commerce and the Institute of Book Keepers.57 Figure 1 below shows statistics for courses and degree programmes funded by Christian Care and awarded to some 800 detainees and political prisoners between 1975 and 1980.

As shown in Figure 1, there were some 250 detainees and political prisoners taking correspondence courses and 20 were enrolled for university degrees in 1975.58 The number of political prisoners enrolled for correspondence courses and degrees increased rapidly between 1975 and 1977. From a low figure of 270 in 1975, the number of detainees enrolled rose to a total of 1 150 in 1977 with 550 doing correspondence courses and 600 doing degree programmes as shown in the graph. This was probably due in part to the increase in the number of detainees and political prisoners. In addition, the recipients responded well to the assistance given by Christian Care, hence the increase in the number of students. At independence in 1980, a total number of 800 ex-detainees and former political prisoners had attained either diplomas or degrees. It is important to note that several students could take more than one course hence the number indicated at every point is not isolated from other totals indicated in the graph.

Furthermore, Christian Care's assistance to the ex-detainees and former political prisoners extended beyond the prison bars. In 1978, Christian Care disbursed R$160 000 (Rhodesian Dollars) in relief aid to the released detainees, each being given R$200, to help them cater for their families.59 There were debates within Christian Care regarding decisions on when to stop aid to released persons, with board members suggesting three months, some suggesting twelve months and some even suggesting continuous relief for an indefinite period or 'until such a time when the economic situation in the country improves.'60

Such debates reflect the difference between systematic aid and charity-based aid. In systematic aid, there are usually set agreements on the duration of such aid, as opposed to charity-based aid where the situation on the ground determines when to cut aid. In the end, Christian Care settled for continuous support as far as funds permitted. However, in many instances, the whole family was given allowances for up to six months and school fees for dependents was paid for up to a year.61 If a former detainee secured employment, assistance was given for two months during which time the person was presumed to have settled down in preparation for the resumption of family obligations.62 It is clear that this form of assistance could not sustain the recipients nor could it prepare them for being self-sufficient, hence assistance was categorised as relief aid. Such relief was given to almost every detainee or ex-detainee irrespective of political affiliation.

The nature of goods donated by Christian Care during this peak period of the war also defines the nature of aid at the time. Since the wartime situation created an emergency, Christian Care also disbursed emergency aid to communities in the form of food, blankets, clothes and allowances. Commenting on the response by the general population to Christian Care's appeal for second-hand clothes, the organisation's coordinator for emergency relief noted that,

...people are beginning to understand our alarm at witnessing tribes being left entirely naked in war areas and are coming forward with clothes...the response has been very good but many more clothes are still needed and they are to reach the tribesmen through our appropriate channels.63

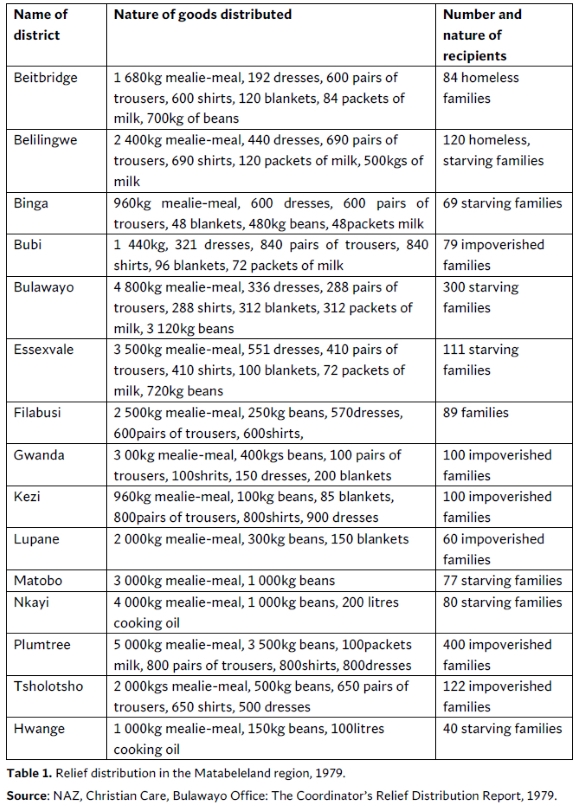

The coordinator's comment reveals that at that particular time, Christian Care was more concerned with assisting the war-torn communities from destitution and hunger through emergency aid. Error! Reference source not found. below summarises the areas covered by relief aid in 1979 as well as the nature of aid given in the Matabeleland region.

The level of need appears to have been at its peak during the years 1977 to 1980. In total, 1 831 families were assisted in the Matabeleland region in 1979 alone. The major causes of hardship were death or disappearance of the breadwinner, loss of livestock and other property such as homes and granaries. It is in such times when Christian Care's thrust was in relief services. As shown in the table above, the composition of Christian Care aid at this point was food aid, clothes, blankets and living allowances for people whose homes were destroyed. The major food distributed was mealie-meal and beans, and in some districts cooking oil. This was in line with the country's staple food so for Christian Care to meet the food requirements of the recipients, it had to donate what the recipients relied upon.

However, it is important to highlight Christian Care's language in describing the nature of recipients. The terminology used in the table above is derived from Christian Care reports. Terms such as poverty-stricken, impoverished and starving families are often conveniently used by Non-Governmental Organisations to advance their agendas. The measure of starvation or poverty might not be universally accepted. In the case of Christian Care, the poverty indicators used to make such conclusions are not given. More so, the 1970s broadly saw a shift in the foreign aid agenda to a poverty focus.64 Since this was a wartime situation where many people fell victim to the war, it is understandable that various communities required emergency aid. The distribution trend shows how entry points used by the liberation fighters were highly affected by the war as a result of the Smith government's response. Such entry points include Hwange and Plumtree.

In 1979 alone Christian Care had an income of Z$300 998.00 and spent as much as Z$105 619.35 on basic commodities such as food, clothing and blankets in Matabeleland.65 As already pointed out, the reason for emergency or relief aid during this time was the war which led to many deaths, destruction of houses and poor harvests which meant that emergency aid was required. This is a reflection on Christian Care's commitment to relief aid at the time.

Christian Care and the post-independence reconstruction process in Matabeleland, 1980-1985

The post-independence government aimed to pursue economic development for the benefit of everyone, as opposed to the colonial government's racial approach. However, it took a whole year before a basic economic blueprint, 'Growth with Equity', was formulated, and another eighteen months to come up with the 'Transitional National Development Plan', to provide the development script.66 Kadhani notes that, 'by 1982, significant internal and external economic imbalances began to show, threatening to escalate pressure for tightening of import controls and also to generate rapid deficit-induced inflation.'67 It is within this context of government attempts at reconstruction and looming economic challenges that like-minded NGOs collaborated to achieve set goals. Organisations like Christian Care became part of the post-war reconstruction process.

The reconstruction process at government level, entailed reopening and refurbishing schools and clinics including construction of new ones as part of social investment. Although the reconstruction process was largely the work of the government at macro level, Christian Care engaged with the communities at micro level. In the Matabeleland region, reconstruction was affected by environmental and political factors which necessitated continuous disbursement of emergency aid. Environmentally, the region was heavily affected by drought between 1982 and 1984 resulting in widespread crop failure.68 Politically, the region was at the centre of political turmoil which characterised Zimbabwe's immediate post-colonial landscape. Popularly known as Gukurahundi, the atrocities claimed about 20 000 lives in the Matabeleland provinces and parts of the Midlands province between 1982 and 1987.69 The Catholic Commission on Justice and Peace concluded that there were two overlapping conflicts taking place in Matabeleland at the time.70 First, there was a conflict between 'dissidents' and government defence units which included the 4thBrigade, 6th Brigade, paratroopers, the Central Intelligent Organisation (CIO) and the Police Support Unit. Secondly, there was fighting between government agencies and those who were thought to be ZAPU supporters.71 The second conflict occurred in several rural areas across Matabeleland and also in some urban areas such as Bulawayo and Midlands and involved the 5th Brigade and CIOs. These multi-layered conflicts proved to be a hindrance to any meaningful reconstruction work.

Reconstruction was necessitated by lack of access to basic needs such as water, health facilities and schools in various communities across the country. Jeffrey Sachs notes that poverty is due to the lack of different kinds of capital such as human, infrastructure, business, natural, public, institutional and knowledge capital.72 Human capital involves health, nutrition and skills while business capital includes machinery, motorised transport used in agriculture, industry and services. Broadly speaking, lack of infrastructure implies the dearth of public services such as water and sanitation, airports, roads, power and telecommunications systems; while natural capital includes the possession of arable land, fertile soils and biodiversity. Public institutional capital involves commercial laws and judicial systems; and knowledge capital includes the know-how to raise productivity in business.73 Reconstruction in independent Zimbabwe would not have been enough without equipping communities with the required capital. In a period when Christian Care activities were concentrating on reconstruction projects such as renovation of schools and hospitals, the construction of additional water sources, among other projects, were necessary to relieve the victims of drought and Gukurahundi.

Several schools re-opening in the communal areas approached Christian Care for funding to repair damaged furniture, broken windows and re-construction of some buildings.74 In response to such calls, Christian Care set up assessment committees across the country. The assessment committees were responsible for evaluating the conditions in areas which required assistance and giving feedback on how best Christian Care could assist.75 Reports from the assessment committees determined the aid flow to the communities from the distribution centres. Christian Care provincial offices remained distribution centres and in the case of Matabeleland, while the Bulawayo Christian Care office was the distribution centre for Bulawayo, Matabeleland North and Matabeleland South.

Having received various calls for assistance in Matabeleland North in 1980, the Christian Care Bulawayo office responded by sending an assessment committee to the province. The assessment committee established that the Field Hospital in Lupane was in dire need of reconstruction. The committee reported that in this district, anthrax, measles, pertussis and malnutrition were widespread.76 In addition, the densely populated areas around the hospital had no means of transport to the hospital and people had to walk long distances to seek medical assistance, so there was an urgent need for an ambulance at the hospital.77 Considering that the Zimbabwean economy was emerging from a war and almost a century of colonialism, the poor economic conditions were hardly surprising. The government was tasked with tackling the problems that mattered most.

During this period of political turmoil (1982-87), the government marginalised the Matabeleland region as far as development efforts were concerned. This was admitted by Prime Minister Robert Mugabe after the political upheavals. He stated that economic development in the Matabeleland region had almost come to a halt, with little or no government effort being channelled towards the region, as opposed compared to other provinces in the country.78 Sachs is of the view that governments are crucial in investing in services such as roads, transport and primary health care but in developing countries they lack the financial means to do so.79 He suggests that financial constraints are the result of an impoverished population in which taxation is not feasible and corruption and debt are widespread.80

However, in the case of the Matabeleland region at the time, circumstances were different - the government intentionally avoided extending development efforts to the region. To fill in the vacuum, Christian Care devoted its aid funds to the reconstruction and renovation of old hospital buildings. In Lupane, it assisted in constructing facilities for patients and suitable space for the storage of medical supplies and hospital equipment.81 It also set up mobile clinics in eight areas across the district with an average of 200 patients being treated in each weekly visit.82 This was crucial considering that the post-independence conflict in Matabeleland had meant the marginalisation of the area by the government.

By 1984 the government had, at national level, trained some 3 800 village health workers who were appointed in rural communities. Through their efforts, an estimated 40 212 Blair toilets were installed and 10 370 protected wells were dug across the country.83 However, as a result of Gukurahundi, the Matabeleland region was marginalised as far as the implementation of such government projects were concerned. Christian Care stepped in to play a critical role in hospital rehabilitation and other reconstruction efforts such as the setting up of mobile clinics in Matabeleland.

In Matabeleland South, Christian Care was also involved in the reconstruction process, a notable case being the Mapani School Project in Gwanda. The school was established in response to the educational needs of refugee children who had fled their homes in areas such as the Gwanda Tribal Trust Land and Mtetengwe Tribal Trust Land at the peak of the war.84 At independence, the school extended its sphere of influence around Gwanda and as far as Beitbridge. The conditions at the school in 1980 were appalling. There were no proper classrooms and some pupils were accommodated in a garage at the back of Mapani store. Lessons were given under trees with no benches and blackboards, and a single toilet had to suffice.85

At the time of independence a policy of free primary education was introduced. Free education had a positive effect by increasing enrolment and literacy rate and a negative effect of straining the economy. Zvobgo argues that while the policy was a 'sound democratic ideal, it was not sound and practical economics, particularly for a developing country.'86 The adverse effect was that of putting the whole population in one socio-economic category and in the end it meant using the scarce resources to help people who least needed help. The government had an increased burden in the education sector and some schools resorted to organisations such as Christian Care for assistance. At Mapani school, Christian Care assisted by financing the construction of three toilets; renting a nearby warehouse which was partitioned into four classrooms; the provision of three mounted hard-board blackboards as well as distributing stationery (supplied by the Red Cross) to the school.87

The transition to development aid did not concentrate on education and health alone but also involved micro agricultural projects to help local communities. These small agricultural projects helped families to meet food requirements and enabled communities to subsist. For example, garden projects were established in Nkayi district, Matabeleland North. One such example was the Vukuzenzele garden, a 2 hectare project approved in 1982 which involved 27 families who grew fresh vegetables and other cash and food crops for consumption and for sale.88 Christian Care's assistance to the community garden included fencing the two-hectare plot, supplying seeds, fertilisers, insecticides, piping and garden tools. It was also responsible for enrolling a member of the project in a course on gardening skills at Solusi Mission.89 Subsequently, Christian Care also supplied cement for the building of a water reservoir and donated an engine and a pump, incurring expenses amounting to Z$1 686.30.90

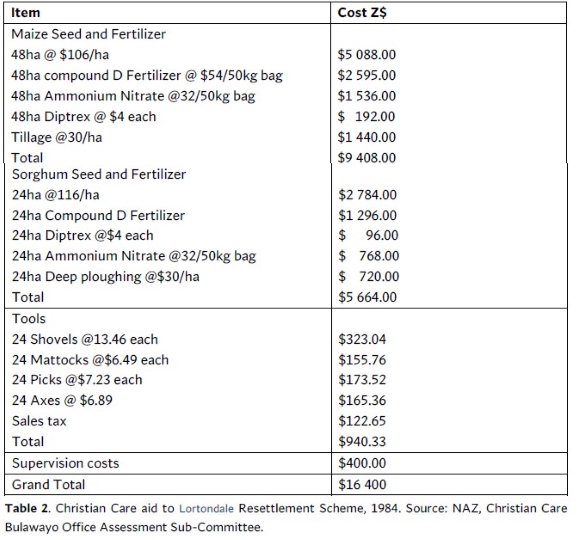

Micro projects were not limited to communal areas. Resettlement schemes were also covered in the reconstruction process. For example, in the Bubi district, Matabeleland North, Christian Care financed the Lortondale Resettlement Scheme to alleviate the effects of the 1984 drought as well as assisting in the reconstruction. The Lortondale Resettlement Scheme was a community of 24 families with a total of 150 people in 1984.91

After the region had been hit hard by the 1983-1984 drought, Christian Care stepped in to assist in the form of the Lortondale Resettlement Scheme. Initially assistance was on relief basis in 1983 before implementing the reconstruction project in 1984. In 1983, Christian Care also facilitated food relief for 148 people in the resettlement scheme, donating foodstuffs such as mealie-meal, cooking oil and beans.92 In 1984, to meet the needs of the community, its focus changed to developmental projects. Christian Care engaged the community in a vigorous intensive land preparation in order to boost production.93 In the crop production project, Christian Care's input included maize seed, sorghum, fertiliser and tools.94 Table 2 below shows the composition of Christian Care aid to the Lortondale Resettlement Scheme.

As shown in Table 2 below, Christian Care assistance to the Lortondale Resettlement Scheme was diverse and substantial indeed. It included major contributions towards the smooth running of the project including seed, fertiliser and all the necessary tools and equipment. This means the project was fully funded by Christian Care in response to the myriad post-independence economic difficulties experienced in the rural settlement. The total contribution of Christian Care to the project, as is shown in the table below, was Z$16 400.

In Matabeleland South, micro projects of the same nature were implemented. Market gardening was introduced in Esigodhini through the Zamani cooperative project in 1984-1985. Comprising 13 families, the aim of project was to produce vegetables and green mealies for local consumption and the local market by utilising a 300mx300m garden plot close to a reliable well within the perimeter of the garden.95 Christian Care's aid to the Zamani cooperative was largely in the form of farming equipment. All in all, Christian Care facilitated the fencing of the 300mx300m area for gardening through the purchasing of fence, gates, gateposts, picks and shovels.96 This meant that the project began its endeavours on a sustainable base since all the prerequisites were made available. Unlike other projects, participants contributed to the success of the project by providing labour and finance. They made their labour available to fence the land and also provided 5% of the total cost of the project.97 This was a highly commendable contribution and helped to reduce aid dependency.

In Kezi district, Matabeleland South, Christian Care aided a group of 120 farmers in the communal lands surrounding the Antelope Mine. The farmers had approached the Agricultural Rural Development Authority (ARDA) in 1980 reclaiming their land which had been alienated by the colonial government. Upon being granted 100 hectares of land, the farmers formed the Maphisa Farming Cooperative.98 The majority of the farmers were former farm workers who lacked capital. A good number had lost large herds of cattle in the 1982-1984 drought. They then approached Christian Care which responded positively by purchasing the necessary equipment and funds for the farming cooperative to begin.99

The composition of Christian Care aid during the first five years of independence was targeted primarily at agricultural production and infrastructure development. This can be seen as an effort to stand in for an 'inactive' government in Matabeleland during the time of Gukurahundi. In the agricultural sector, Christian Care was involved in micro projects such as farming cooperatives and market gardening where it assisted communities with the necessary infrastructure and equipment for the projects before handing over the running of the entire project to the community. As noted above, in the infrastructural sector, Christian Care was involved in the rehabilitation of schools and hospitals. However, this did not signal an end to relief aid since Christian Care often engaged in feeding schemes as a response to drought.100 By and large, the nature of Christian Care aid during this period reflects a transition from relief to development aid.

Complementing government efforts: Christian Care aid and Zimbabwe's first Five-Year National Development Plan, 1986-1990

During the period 1986-1990, Christian Care was mainly concerned with complementing the government of Zimbabwe's efforts in rural development. The conflict in the region was de-escalating, with the Unity Accord eventually being signed in 1987 marking the end of the conflict. By this time, some government development projects were being extended to the Matabeleland provinces albeit at planning level. Christian Care's major project countrywide during this time was the Food Production and Drought Rehabilitation scheme named Operation Joseph.

Outside Operation Joseph, Christian Care intensified its project approach to poverty alleviation especially in the Matabeleland region. It engaged the government's economic blueprint, the First Five Year National Development Plan (FFYNDP) 1986-1990 to establish areas where the organisation's aid could be directed. This was done mainly through water development programmes in various rural districts of the two Matabeleland provinces. One of the criticisms levelled against charity-based aid such as that by Christian Care is that sometimes the charity organisations represent the interest of their donors' governments while ignoring the local context.101 In this case, Christian Care stood the test of such criticism.

The FFYNDP was a strategic plan devised by government to achieve economic development in the period 1986-1990. There were three production sectors at the core of the development strategy, namely agriculture, manufacturing and mining. Of these three Christian Care, at national level, dealt mainly with agriculture and to a limited extent manufacturing. Examples of manufacturing assistance at national level were a brick making project in Masvingo and a building and block making cooperative in Mutare.102 In the Matabeleland region, however, Christian Care focused mainly on agriculture related projects due to low rainfall patterns in the region.

The government blueprint identified the Matabeleland provinces as a region characterised by low rainfall and persistent drought. It further noted that the region had potential for growing drought-tolerant crops, cattle production as well as the production of other small livestock such as sheep, goats and pigs.103 The government intended to provide the infrastructure necessary to enhance the development of the identified areas. By 1986, there were at least 30 major dam sites in the region of which only a few had been built. It was estimated that uncommitted surface water available for agriculture and other development was about 7.8 billion cubic metres which was enough to irrigate about 55 086 hectares.104 Government planned to develop irrigation schemes at Fanisoni, Lukosi, Tshongwe, Simangani, Moza in Bulilimangwe District, Lupane, Mount Edgecombe in the Matopos district, Swole Shoki, Bert Knolt and Shashi in the Beitbridge District, as well as rehabilitating the Gwanda and Beitbridge irrigation schemes.105

The Zimbabwean Government also aimed at creating a suitable environment for a high and sustainable growth in the agricultural sector by providing credit facilities to small-scale resettlement and communal farmers, reviewing the pricing policy for agricultural produce annually, promoting research activities relevant to the sector and to initiate the development of irrigation schemes. In addition, to promote the marketing of agricultural products in Matabeleland, it planned to erect a new Bulawayo dairy enterprise, and to provide additional holding grounds (as a result of Zimbabwe's entry into the European Economic Community beef market). A new abattoir was to be built at Bulawayo.106

At a regional level, the two provinces of Matabeleland approached Christian Care, among other development agencies to request their cooperation in the implementation of the envisaged government policies. Christian Care was always represented at provincial and district meetings where government strategies and policies were outlined. In 1988, the Matabeleland South Provincial Development Committee acknowledged the role of Christian Care, among other NGOs, throughout the province in augmenting primary water supplies107 and the Plumtree District Nutrition Coordinator engaged Christian Care in the implementation of nutrition programmes such as nutrition gardens.108 The Lupane District administrator admitted that through Christian Care projects, local communities became accustomed to 'nutritious foods like beans and groundnuts as protein foods' and that this gave nutrition coordinators a guide to nutrition education that could be used to spread this information to people to remote areas.109 This is evidence of cordial church-state relations after Gukurahundi.

Christian Care was concerned about developmental activities which had a bearing on the FFYNDP priorities. The chairperson of the organisation noted that it was 'essential that all development work Christian Care undertakes is in harmony with Central Government's development priorities.'110 He indicated that there was as yet insufficient information provided on many small agricultural projects that were part of the government's blueprint and could be adopted by rural communities. Christian Care focused primarily on these, arguing that they could become the basis of community development and self-reliance - with the ultimate aim of poverty reduction.111

Christian Care aimed to raise the income of peasants through increased agricultural production and the creation of employment by embarking on meaningful, income generating projects and relevant training programmes. Another avenue of progress was to establish small irrigation schemes and the rehabilitation of old schemes.112 This was feasible if a vigorous project approach was followed with projects such as water development programmes and the construction of dams to enhance crop and livestock production. Notable water development programmes undertaken at the time included the Gwanda Ward 11 (Matshetsheni) Water Programme and the Sifini Dam project. Their development and the role played by Christian Care is discussed below. Once again, this NGO was prominent in the promotion of the projects.

Christian Care's water development programmes: Gwanda Ward 11 (Matshetsheni) Water Programme

Gwanda Ward 11 is in the Gwanda district of Matabeleland South province, an area which falls under Agro-ecological Region 5. It is characterised by low rainfall of +/-400mm per annum.113 Matshetsheni communal lands, where the project was carried out, had a population of approximately 8 000 people in 1986. Dominant crops grown in the area include maize, sorghum, finger millet and sunflower, with yields gradually decreasing due to recurrent droughts.

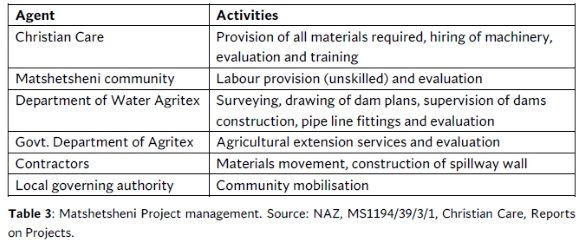

The water development project aimed to construct four dams (Mabilila, Mantantshaneni, Machibini and Tshendambuya) to store water for livestock, human consumption and nutritional gardens. The project was implemented in the period between 1986 and 1988. To make these ambitious plans a reality, the Matshetsheni community approached Christian Care for assistance. The project design agreed upon between Christian Care and the Matshetsheni community entailed the construction of four dams in five months. Table 3 below indicates how the project was managed by the various agencies.

As shown in Table 3 above, the water development programme involved different agencies. Christian Care provided the funds, while the government's Department of Water and Agritex provided technical expertise. The community, (residents, village heads and sub-chiefs) provided unskilled labour and formed committees to monitor operations. This project epitomised government/NGO/ local communities cooperation. The dams had a catchment area ranging from 3-7km2, a maximum probable flood area, ranging from 100-112.5m3/s, a design flood, 40-85m3/s, a wet freeboard of 1m, 5 to 8m dam weir height and 40 to 150m dam weir length.114

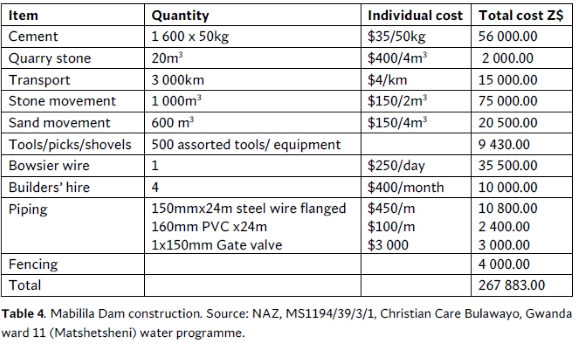

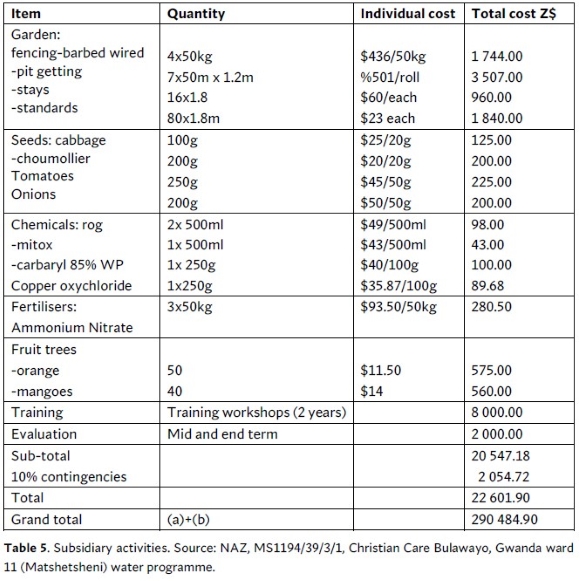

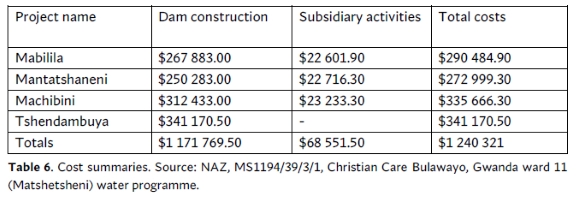

Below are three tables showing the construction inputs and costs for Mabilila Dam showing how the four dams were constructed; a subsidiary of activities after dam construction; and a summary of the costs of the whole project.

As shown in tables 4, 5 and 6, the Gwanda Ward 11 water programme was a macro-project. Christian Care provided Z$1 240 321. This was for the socio-economic benefit of the community. Once installed the project accessed water from a source +/-5km away.115 The +/-200 000m3 water storage also benefited the community through livestock production and gardening. In addition, vegetable gardens were established for community subsistence and income generation. The Christian Care annual report of 1992 indicates that by September 1992, the benefits obtained from the water development project had surpassed the funds injected.116 The development agents involved in this project reflect a public-private partnership in development whereby government agents partnered NGOs to enhance economic development. However, the amount contributed by Christian Care alone shows the government's incapacity to fund such community projects and this gap was filled by NGOs. This demonstrates that in the first decade of independence NGOs, in particular Christian Care, played a critical role in the economic reconstruction process.

Another water development project was the Ingwezi Water Programme, located in the Ingwezi communal area, 10 km south of Plumtree, which falls under Natural Region 4. The programme aimed to provide water for domestic consumption, livestock consumption and vegetable production for a community of approximately 2 000 people.117 The average rainfall of the area is between 500 and 600mm per year and the soils are mainly sandy with scattered sodic soil.118 The programme was undertaken because of siltation of a weir constructed in 1963 and the insufficient water supply from the Mhlanga Dam. In 1987 the Ministry of Water and Development came to the community's rescue by constructing a single borehole. This proved inadequate, and the community appealed to Christian Care for assistance.

In line with Christian Care's water development programmes, the Ingwezi community was assisted with borehole drilling. Christian Care carried out a geographical survey and identified six sites of borehole drilling which could benefit an estimated 150 families (810 people).119 The six boreholes were installed and fitted with hand pumps for easy usage and the community immediately established gardens near each borehole. The NGO's aid to the Ingwezi community water programme involved the supply of screen to sift river sand, drilling and installing boreholes, supplying bush pumps and piping, supplying materials for headworks and the supply of fencing for pump stands.120 The Ingwezi community participated actively in the programme through road repairs for easy access, sifting river sand for the borehole gravel pack, supplying bricks for lining drain and cattle troughs, fencing pump stands, and by constructing headworks together with the District Development Fund (DDF). They also provided the required labour. Like in other Christian Care projects of this nature, the involvement of the DDF reflects a tripartite relationship between the donor, the community and the government. It facilitates an easy handover-takeover of the programme from the donor to the community where DDF would then be entrusted with the role of servicing the infrastructure. A mutual accountability to the success or failure of the Ingwezi programme was, as a result, visible from design to implementation. The results of the programme can therefore be mutually shared by the donor and the community, resulting in programme effectiveness.

Judging by its impact, the Ingwezi water programme provides significant evidence to the claim that aid works when applied correctly. The programme reduced the distance travelled by people to fetch water considerably. In this case the programme was a boon to the women, considering their role in the homestead, where they are preoccupied with gendered roles such as kitchen chores. Riddell and Robinson argue that an effective donor-funded project should, among other things, meet the demands and requirements of women in the society.121 Moreover, the Ingwezi water programme's impact was in line with the programme objectives. Among the objectives of the project was to provide clean, dependable water for the community. At each borehole, Christian Care also constructed water troughs for livestock. The programme resulted in improved availability of clean water and soon there were flourishing nutrition gardens around the high-yielding boreholes.122 Christian Care's aid, in this case, was very effective in the short term, but the programme's sustainability should be evaluated by making an assessment of the economic and environmental factors.

As a shift from relief to development aid, Christian Care implemented an ambitious project-approach to poverty reduction which saw the implementation of water development programmes in the form of dam construction. In Matabeleland, the grand total for all these projects reached Z$21 706 950.80 by 1993.123 It should be noted that the 1992 drought affected Christian Care's projects and that under the circumstances the organisation had to focus on relief programmes such as supplementary feeding to ensure the survival of drought victims. The volume of such aid shows how Christian Care was committed to complementing government efforts. Unlike at its formation, where church-state relations were hostile, the church and the state lived in harmony especially after Gukurahundi.

In complementing government efforts, Christian Care also engaged other development agents/ donor agencies. In the implementation of Sifini Dam in the Insiza district of Matabeleland South. Here Christian Care partnered with Africare, a donor agent, in funding the programme. Sifini Dam was a water development programme carried out between 1988 and 1990. The 112 700m3 dam was set to benefit Wards 7 and 12 of the district, with a combined population of 12 470 in 1988.124 Christian Care and Africare shared the burden of funding the programme equally, a project which cost Z$297 119.20.125

The cooperation between Christian Care and Africare in implementing this project was a step towards networking with other NGOs, a move that had been discussed within Christian Care circles but rarely implemented. It was a significant step in the development of Christian Care aid in Matabeleland. Besides Africare, the implementation of the project was also through the partnership of public and private institutions, government departments such as DDF and Agritex as well both traditional and government structures of Village Development Committees (VIDCOs) and Ward Development Committees (WARDCOs). The implementation of Sifini Dam, therefore, provided a great step in the development of Christian Care aid. VIDCOs and WARDCOs, being partnerships of traditional and government authorities, were responsible for organising labour at village and ward level. DDF was responsible for surveying and pegging of the dam while Agritex-trained the members in water management and gardening.126

The Sifini Dam project considered women and children as 'vulnerable' groups, hence its significance. Among its objectives were to provide water for gardening and growing vegetables for local consumption and sale as well. There were also plans afoot to utilise the water in the dam for livestock and human consumption. Since women bore the brunt of walking long distances to fetch water, and subsistence gardening has always been female dominated, the project was also welcomed by the local women. It was significant that of the 12 470 people resident in the two wards, 70% comprised women and children.127 During the Christian Care 40th anniversary celebrations in 2007, Alfred Knottenbelt, a former chairman of the organisation, lauded the fact that Christian Care was one of the few organisations that represented women's interests in rural areas in the late 1980s.128 Although this is the voice of a Christian Care representative, which should, perhaps be treated with caution, one cannot easily disregard Christian Care's sterling contribution towards the welfare of women in rural areas.

This final section of the paper focused on Christian Care's engagement with government programmes. In 1986 Christian Care engaged the government's economic development, FFYNDP, to complement government efforts at development. Between 1986 and 1993, Christian Care aid played a significant role in filling the gaps left by the government's efforts towards community development. This was done through a vigorous project approach towards development in general and the implementation of water development programmes in particular. There is always a tendency by scholars to classify aid by the way it is disbursed, whereby charity/welfare organisations become centres for emergency aid and multilateral institutions and governments are regarded as distributors of development aid. As revealed in this paper, aid is not defined by the system of disbursement but by the nature and composition of what has been disbursed.

Conclusion

The nature and composition of Christian Care aid in Zimbabwe between 1967 and the 1990s shifted in line with local demands. At its inception, Christian Care was concerned with assisting the victims of war, particularly those imprisoned or detained without trial. It assisted them with access to education while in prison and food for their families, bearing in mind that the majority of them were bread winners. This was a crucial gap in emergency aid because other charity organisations like the Red Cross focused on those injured during the war. As shown in this paper, Christian Care was set up to respond to an emergency, the liberation war. With time, after independence, the organisation changed its approach but retained its agenda to suit local demands. At the peak of the Gukurahundi atrocities in the Matabeleland region, Christian Care assisted the needy, helping local people to start small projects such as market gardening. When the conflict drew to an end, the organisation began to complement government efforts, working closely with the government's economic blueprint and departments in implementing development projects. The development of Christian Care aid in Matabeleland between 1967 and 1990, therefore, shows how charity aid, if well managed, can respond effectively to the demands of the local people.

REFERENCES

Agere, S.T. 'Progress and Problems in the Health Care Delivery System in Zimbabwe', in The Political Economy of Transition, 1980-1986, edited by I. Mandaza. Dakar: Codesria Book Series, 1986. [ Links ]

Alexander, J. and McGregor, J. 'War Stories: Guerilla Narratives of Zimbabwe's Liberation'. History Workshop Journal, 57 (2004). [ Links ]

Alexander, J. McGregor, J. and Ranger, T. Violence and Memory. One Hundred Years in the 'Dark Forests' of Matabeleland. Oxford: James Currey, 2000. [ Links ]

Alexander, J. 'Dissident Perspectives on Zimbabwe's Post-Independence War'. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 68, 2 (1998), 151-182. [ Links ]

Alexander, J. 'The Noisy Silence of Gukurahundi: Truth, Recognition and Belonging'. Journal of Southern African Studies, (2021), 1-23. [ Links ]

Bhebe, N. and Ranger, T. (eds), Society in Zimbabwe's Liberation War. London: James Currey, 1996. [ Links ]

Bhebe, N. and Ranger, T. (eds), Soldiers in Zimbabwe's Liberation War. London: James Currey, 1995. [ Links ]

Dorman, S.R. Understanding Zimbabwe. From Liberation to Authoritarianism. London: Hurst & Company, 2016. [ Links ]

Dube, T. 'Gukurahundi Remembered: The Police, Opacity and the Gukurahundi Genocide in Bulalimamangwe District, 1982-1988'. Journal of Asian and African Studies, (2021), 1848-1860. [ Links ]

Easterly, W. White Man's Burden. Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest have Done so Much Ill and so Little Good. New York: Penguin Books, 2006. [ Links ]

Gulrajani, N., 'Transcending the Great Foreign Aid Debate: Managerialism, Radicalism and the Search for Aid Effectiveness'. Third World Quarterly, 32, 2 (2011), 199-216. [ Links ]

Hulme, D. and Edwards, M. 'NGOs, States and Donors: An Overview', in NGOs, States and Donors. Too Close for Comfort? edited by D. Hulme and M. Edwards, London: Macmillan Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Kinloch, G.C. 'Problems of Community Development in Rhodesia'. Community Development Journal, 7, 3 (1972), 189-193. [ Links ]

Kriger, N.J. Zimbabwe's Guerrilla War. Peasant Voices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Linden, I. The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe. London: Longman, 1980. [ Links ]

McLaughlin, J. On the Frontline. Catholic Missions in Zimbabwe's Liberation War. Harare: Baobab Books, 1996. [ Links ]

Moyo, D. Dead Aid. Why Aid is Not Working and How There is Another Way for Africa. London: Penguin Books, 2009. [ Links ]

Mugabe, R. 'The Unity Accord: Its Promise for the Future', in Turmoil and Tenacity. Zimbabwe, 1890-1990, edited by C. Banana. Harare: The College Press, 1989. [ Links ]

Munochiveyi, M. Prisoners of Rhodesia: Inmates and Detainees in the Struggle for Zimbabwean Liberation, 1960-1980. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, N. 'The Gukurahundi "Genocide": Memory and Justice in Independent Zimbabwe'. PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 2019. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. 'Rethinking Chimurenga and Gukurahundi in Zimbabwe: A Critique of Partisan National History'. African Studies Review, 55, 3 (2012), 1-26. [ Links ]

Ranger, T. Voices from the Rocks. Nature, Culture and History in the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe. Harare: Baobab, 1999. [ Links ]

Riddell R. and Robinson, M. 'The Impact of Non-Governmental Organisations' Poverty Alleviation Projects: Results of the Case Study Evaluations', Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 68 (1992). [ Links ]

Sachs, J.D. End of Poverty. Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: The Penguin Press, 2005. [ Links ]

Sapire, H. and Saunders, C. (eds). Liberation Struggles in Southern Africa in Context: New Local, Regional and Global Perspectives. Claremont: UCT Press, 2013. [ Links ]

Shorter, A. The Cross and Flag in Africa: The 'White Fathers' During the Colonial Scramble (1892-1914). Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2006. [ Links ]

Takuva, T. 'A Social, Environmental and Political History of Drought in Zimbabwe, c.1911 to 1992'. PhD thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2022. [ Links ]

Tandon, Y. Ending Aid Dependence. Nairobi: Fahamu Books, 2008. [ Links ]

Urban-Mead, W. The Gender of Piety: Family, Faith and Colonial Rule in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Weil, U. 'Christian Care in Rhodesia'. Race Today, 3-4 (1971), 127-129. [ Links ]

Whitefield, L. 'Reframing the Aid Debate: Why Aid Isn't Working and How it Should be Changed'. DIIS Working Paper, 34, (2009). [ Links ]

Zvobgo, R. 'Education and the Challenges of Independence in Zimbabwe', The Political Economy of Transition, edited by I. Mandaza. Dakar: Codesria Book Series, 1986. [ Links ]

* Tinashe Takuva (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8603-2617). He obtained a PhD in History from Stellenbosch University (2022). His research focuses broadly on environmental, economic and social histories of southern Africa and Zimbabwe in particular in 20th century and explores the interconnectedness of environmental, social, political and economic forces in shaping community relations. Email: Tinashe.takuva2@gmail.com

1 I use the term 'development aid' in this article to show the difference in the kind of aid disbursed by Christian Care over the years. In the context of this article, development aid is aimed at reconstruction and construction of infrastructure and funding of community projects as opposed to food handouts, clothes and allowances. This is a working definition for the purposes of this article since it is not my aim here to engage in debates and theories of development at length but to explore the narrative of Christian Care aid in Zimbabwe from the organisation's perspective.

2 Gukurahundi was a code name for the atrocities committed by the Robert Mugabe led government of Zimbabwe in the Matabeleland provinces and parts of the Midlands Province between 1982 and 1987. For more on this, see for instance J. Alexander, 'The Noisy Silence of Gukurahundi: Truth, Recognition and Belonging', Journal of Southern African Studies (2021), 1-23; S.J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 'Rethinking Chimurenga and Gukurahundi in Zimbabwe: A Critique of Partisan National History', African Studies Review, 55, 3 (2012), 1-26; J. Alexander, 'Dissident Perspectives on Zimbabwe's Post-Independence War', Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 68, 2 (1998), 151-182; and T. Dube, 'Gukurahundi Remembered: The Police, Opacity and the Gukurahundi Genocide in Bulalimamangwe District, 1982-1988', Journal of Asian and African Studies (2021), 1848-1860.

3 The sources for this article are limited to archival material, the majority of which are Christian Care documents. This limits the scope of the study to the evolution of Christian Care aid, ignoring the interface between Christian Care and the recipients. I was unable to carry out oral interviews because of the language barrier. By limiting this study to the transformation of Christian Care aid, the article provides an organisational history in the context of war, repression and marginalisation. Future research can build on this study to explore the recipients' (both individuals and communities) interaction with Christian Care aid and to investigate its effectiveness.

4 U. Weil, 'Christian Care in Rhodesia', Race Today, 3/4 (1971), 127-129.

5 The guerilla war, sometimes referred to as the 'Bush War' or the Second Chimurenga, was a war of liberation fought between the indigenous African soldiers (who preferred the term guerilla because of the guerrilla warfare strategy) and the white minority government. For a detailed account of the war, see H. Sapire and C. Saunders (eds), Liberation Struggles in Southern Africa in Context: New Local, Regional and Global Perspectives (Claremont: UCT Press, 2013); N. Bhebe and T.O. Ranger (eds), Soldiers in Zimbabwe's Liberation Army (Harare: UZP, 1995); J. Alexander and J. McGregor, 'War Stories: Guerilla Narratives of Zimbabwe's Liberation', History Workshop Journal, 57 (2004).

6 Weil, 'Christian Care in Rhodesia', 127-129.

7 National Archives of Zimbabwe (hereafter NAZ), MS1184/1/7, General Correspondence File, 1984.

8 Weil, 'Christian Care in Rhodesia', 127-129

9 NAZ, Historical Manuscripts MS Series, A-L.

10 NAZ, MS1191/3/3/1, Bulawayo Emergency Relief Committee: 1979-1980.

11 D. Moyo, Dead Aid. Why Aid is not Working and How there is Another Way for Africa (London: Penguin Books, 2009); Y. Tandon, Ending Aid Dependence (Nairobi: Fahamu Books, 2008).

12 W. Easterly, White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest have Done so Much Ill and so Little Good (New York: Penguin Books, 2006): L. Whitefield, 'Reframing the Aid Debate: Why Aid isn't Working and How it Should be Changed', DIIS Working Paper, No. 34 (2009); and N. Gulrajani, 'Transcending the Great Foreign Aid Debate: Managerialism, Radicalism and the Search for Aid Effectiveness', Third World Quarterly, 32, 2 (2011), 199-216.

13 Moyo, Dead Aid, 7.

14 Moyo, Dead Aid, 7-8.

15 D. Hulme and M. Edwards (eds), 'NGOs, States and Donors: An Overview', in NGOs, States and Donors: Too Close for Comfort? (London: Macmillan Press, 2013).

16 Moyo, Dead Aid, 8.

17 Moyo, Dead Aid, 9.

18 Moyo, Dead Aid, 7.

19 I. Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe (London: Longman, 1980), 61.

20 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 60.

21 See for instance A. Shorter, The Cross and Flag in Africa: The 'White Fathers' during the Colonial Scramble (1892-1914) (Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2006.)

22 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 3.

23 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 74.

24 J. McLaughlin, On the Frontline: Catholic Missions in Zimbabwe's Liberation War (Harare: Baobab Books, 1996).

25 For more on the community development approach, see for instance G.C. Kinloch, 'Problems of Community Development in Rhodesia', Community Development Journal, 7, 3 (1972), 189-193.

26 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 74.

27 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 183.

28 Linden, The Catholic Church and the Struggle for Zimbabwe, 183.

29 McLaughlin, On the Frontline, 24.

30 McLaughlin, On the Frontline, 278.

31 W. Urban-Mead, The Gender of Piety: Family, Faith and Colonial Rule in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2015), 182.

32 Urban-Mead, The Gender of Piety, 209.

33 Urban-Mead, The Gender of Piety, 210.

34 Urban-Mead, The Gender of Piety, 225.

35 These two were military wings for the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) parties respectively.

36 Bhebe and Ranger, Soldiers in Zimbabwe's Liberation War.

37 M. Munochiveyi, Prisoners of Rhodesia: Inmates and Detainees in the Struggle for Zimbabwean Liberation, 1960-1980 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 31.

38 Munochiveyi, Prisoners of Rhodesia, 122.

39 Munochiveyi, Prisoners of Rhodesia, 122.

40 N.J. Kriger, Zimbabwe's Guerrilla War: Peasant Voices (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

41 Kriger, Zimbabwe's Guerrilla War, 240.

42 N. Bhebe and T.O. Ranger (eds), Society in Zimbabwe's Liberation War (London: James Currey, 1996).

43 Bhebe and Ranger, Society in Zimbabwe's Liberation War.

44 S.R. Dorman, Understanding Zimbabwe: From Liberation to Authoritarianism (London: Hurst & Company, 2016).

45 Dorman, Understanding Zimbabwe, 22.

46 Dorman, Understanding Zimbabwe, 24.

47 Dorman, Understanding Zimbabwe, 28.

48 Dorman, Understanding Zimbabwe, 29.

49 T. Ranger, Voices From the Rocks: Nature, Culture and History in the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe (Harare: Baobab, 1999), 229.

50 J. Alexander, J. McGregor and T. Ranger, Violence and Memory. One Hundred Years in the 'dark forests' of Matabeleland (Oxford: James Currey, 2000).

51 Dube, 'Gukurahundi Remembered', 1848-1860.

52 N. Ndlovu, 'The Gukurahundi "Genocide": Memory and Justice in Independent Zimbabwe' (PhD Thesis, University of Cape Town, 2019).

53 NAZ, Historical Manuscripts, MS Series, A-L.

54 NAZ, MS 1192, Political Prisoners assisted by Christian Care.

55 NAZ, MS 1192, Political Prisoners assisted by Christian Care.

56 NAZ, MS 1192, Political Prisoners assisted by Christian Care.

57 NAZ, MS308/62/1, Christian Care, 'Report of the Education and Employment Survey on Release: Detainees and Political Prisoners in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, 1972-1980'.

58 NAZ, MS308/62/1, Christian Care, 'Report of the Education and Employment Survey on Release: Detainees and Political prisoners in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, 1972-1980'.

59 National Observer, 29 July, 1978.

60 NAZ, MS1194/5/1, National Chairman's Report 1977-1978.

61 National Observer, 29 July 1978.

62 National Observer, 29 July 1978.

63 Zimbabwe Times, 28 September 1978.

64 Moyo, Dead Aid, 15-17.

65 Zimbabwe Times, 28 September 1978.